Abstract

Background

This study examined the clinical effects of leuprolide acetate in sexual offenders with paraphilic disorders evaluated by means of objective psychiatric assessment.

Methods

The subjects of this study were seven sexual offenders who were being treated by means of an injection for sexual impulse control by a court order. They had been diagnosed with paraphilia by a psychiatrist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) and had been put on probation by the Ministry of Justice between January 2016 and December 2016.

Results

After twelve months, we observed significant improvement in symptoms, as decrease of abnormal sexual interest and activity, sexual fantasy, Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S), and Clinical Global Impression-Impulsivity (GCI-I). There were a mild feminization of the body shape, feelings of fatigue, and mild hot flushes. No other adverse effect was reported.

Conclusion

These results suggested that the clinical effects of leuprolide acetate in sexual offenders might be an effective treatment and safety strategy.

Keywords: Leuprorelin, Leuprolide Acetate, Sexual Offenders, Paraphilia

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sexual offenders are different from paraphilic disorders. Although many sexual offenders have paraphilic disorders, they generally are more aggressive than paraphilic disorders, and paraphilic disorders often show abnormal sexual fantasies or desires without acting out.1 It has been known that more than half of sexual offenders have paraphilia and that most paraphilic disorders have a high rate of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders.2 On the other hand, it has been long reported that most sexual offenders have at least one other psychiatric disorder, suggesting an association. The comorbid psychiatric disorders of sexual offenders include depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, alcohol and substance use disorder, impulse control disorder, conduct disorder, and personality disorder in addition to paraphilic disorder.3,4 Identifying paraphilic disorder or a psychiatric disorder that a sexual offender has is clinically important, because treatment of the accompanying paraphilic disorder or psychiatric disorder in a sexual offender may help accomplish secondary improvement of the symptoms of sexual abnormality.

The effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) preparations on patients with paraphilia has rarely been studied, because the population of paraphiliacs are hardly collected because of their clinical characteristics, and most of them refuse hormone therapy. Thibaut et al.5,6 had administered triptorelin, one of the GnRH depot formulations, to six severe paraphiliacs for seven years and reported that all types of abnormal sexual behavior had disappeared in five of the subjects. There were a few studies of drug treatment of paraphilia in Korea and other countries, but the clinical effect of GnRH depot formulations on paraphilia has not been reported in Korea. In this study, leuprorelin, a GnRH depot formulation, was administered to sexual offenders with paraphilia who were under compulsory GnRH treatment according to a legal order for 12 months. Otherwise supportive psychological treatment was applied to all 7 subjects. The supportive psychological treatment took about 1 time per month and about 1 hour per session. The contents of treatment were supportive psychotherapy or cognitive behavior therapy such as psycho-education, emotional support, and contingence management etc.

Various types of psychiatric evaluations performed with the subjects showed a significant decrease in sexual desire and behavioral problems. The present study is the first research conducted in East Asia to verify the long-term (12 months) clinical effect of the GnRH injection evaluated by means of an objective psychiatric assessment performed by a psychiatrist.

METHODS

Participants

The subjects of this study were seven sexual offenders who were being treated by means of an injection for sexual impulse control by a court order. The research subjects were nine patients who had been diagnosed with paraphilia by a psychiatrist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). The sexual offenders with paraphilia who had received a psychiatric evaluation, or had been put on probation by the Ministry of Justice between January 2016 and December 2016, were personally interviewed.

Assessments

Epidemiological questionnaire

The epidemiological questionnaire used in the present study included questions about the information such as sex, age and intelligence quotient (IQ), etc.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)-2

The MMPI is an objective personality test that is the most widely used and has been the most actively studied. In the 1940s Hathaway and Mckinley at the University of Minnesota in the United States the originally made the MMPI as a method for the objective measurement of abnormal behavior. Thus, the primary purpose of the MMPI is a measurement for psychiatric diagnosis and classification, and it is not for the measurement of general personality characteristics. However, under the assumption that the concept of pathologic classification can be applied to the behavior explanation of normal persons to a certain extent, general personality characteristics can also be evaluated through the MMPI to a certain extent. This response is scored based on 10 clinical scales for measuring the type of major abnormal behavior and four validity scales for measuring the test-taking attitude of a subject. In Korea, the MMPI that was standardized in 1989 by the clinical psychology department of the Korean Psychological Association has been widely used in clinical and counseling applications in hospitals and schools.7 The MMPI consists of 567 questions; and for each question, a subject is made to select an answer between ‘Yes’ and ‘No.’

Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R)

The PCL-R is known to be the best instrument for predicting the recidivism rate of violent crimes, such as sexual crime.8 The original version of the PCL had 22 questions, but 12th PCL-R has 20 questions. The PCL-R diagnoses if a person is a psychopath by using a semi-structured interview and additional information. Each item is rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 2 points. The rater is supposed to rate each item on the basis of not only the interview with the subject but also the other information as much as possible, including the subject's student records, police records, juvenile crime records, living attitude in jails, offender classification results, and the visiting interview by families and relatives. A person with a total PCR-R score of 25 or higher is classified as highly psychopathic.

Sex Addiction Screening Test (SAST)

The SAST, developed for screening sex addiction by Carnes et al.,9 is a self-rating scale for the self-assessment of sex addiction. The SAST includes 20 questions to which a subject may respond with the answers Yes or No. A person with a total SAST score of 13 or higher can be classified as a sex addict.10

Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (WSFQ)

The WSFQ, a self-report questionnaire about sex fantasies, is used to quantitatively assess sexual desire, sexual preference, and sexual activity.11 The WSFQ is one of the clinical self-report scales about sexual fantasy most frequently used in Korea. The questionnaire includes a total of 40 questions that are rated in a six-point Likert scale (0, not at all, to 5, regularly). The questions are classified by four sub-scales, which are 1) exploratory factor, e.g., group sex, sexual promiscuity, mate-swapping; 2) intimate factor, e.g., kissing passionately, oral sex, masturbation, and sex outdoors; 3) impersonal factor, e.g., sex with strangers, watching others engage in intimate behavior, fetishism, and looking at obscene pictures; and 4) sadomasochistic factor, e.g., whipping, spanking, or being forced to have sex. The questionnaire showed excellent reliability through multiple assessments with men.12 The sum of all 40 items provides a total score that may reflect overall sexual drive.11

Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI)

This BDI was developed by Beck to measure the degree of adult depression.13 In Korea, Lee and Song14 classified scores over 16 as a mild depressive state.

Beck's Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

This is a useful assessment tool to measure clinical anxiety. It also has the advantage to measure the anxious state of adults never having been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. It was developed by Beck et al.15 and translated into Korean by Yook and Kim.16 The reliability and validity of the inventory were studied. In the case of the anxiety inventory scale, the scores 22–26 indicate a little high anxiety, scores 27–31 indicate a considerably very high anxiety, and scores 32 or higher indicate extremely high anxiety.

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSI)

The 19-item BSI was used to evaluate Month 12 intensity of the patients' specific attitudes, behaviors, and plans to commit suicide.17,18 These 19 items assess such characteristics as the ‘Wish to Die,’ ‘Wish to Live,’ ‘Reason for Living or Dying,’ ‘Active Suicidal Desire,’ ‘Passive Suicidal Desire,’ etc. Each item consists of three options, which are rated on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2, and each item is graded according to the intensity of the suicidality. Total scores are calculated by summing the 19 ratings, and these total scores can range from 0 to 38. The first 5 items are used to screen for attitudes toward living and dying, and only patients who report a desire to make an active (item no. 4) or passive (item no. 5) suicide attempt are rated on items No. 6–19.

Malach Burnout Inventory

Burnout was assessed by using the Malach Burnout Inventory developed by Malach et al.19 The Malach Burnout Inventory assesses emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment. It was translated into Korean by Kang and Kim20 and the reliability of the translated version was validated. The assessment is performed on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). A higher Malach Burnout Inventory score indicates a higher degree of burnout.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS)

The scale was developed by Barratt et al.21 for the measurement of impulsiveness, and Lee22 adapted it to Korean circumstances. It consists of 23 questions, and three subordinate factors: six questions for measuring cognitive impulsiveness (e.g., “I easily lose interest when thinking of complicated things”), eight questions for measuring motor impulsiveness (e.g., “It is hard to be seated on a spot for a long time”), and nine questions for measuring non-planning impulsiveness (e.g., “I start another task before finishing a task”). Likert-type four-point scale was used, where the score ranged from ‘It never does’ (1 point) to ‘It always does’ (4 points). A higher score represents higher impulsiveness. The Cronbach's α coefficient at the time of the Korean version test development was 0.82, which were relatively stable.

Rosenberg's Self-esteem Inventory (RSI)

RSI is a test for measuring the degree of self-esteem, the pattern of self-acceptance for an individual, and for measuring overall self-esteem. The inventory was devised in 1965 by Rosenberg in the United States, and Lee23 standardized it to Korean circumstances. It consists of a total of 10 questions (five questions on positive self-esteem and five questions on negative self-esteem) in a self-report format. Zero to three points is assigned to one question, and the range of the total score is 0–30 points. A high score indicates high self-esteem, with previous research reporting a reliability of 0.79.24

Korean Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Scales (K-AADHS)

Developed by Murphy and Barkley, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), K-AADHS is a self-report assessment. The scales, with 18 items, is proven for its validity in differentiating adults with ADHD from those without, and designed to effectively differentiate three subtypes of ADHD: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined hyperactive-impulsive, and inattentive. Korean standardization has been achieved by Kim.25

Satisfaction with the Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS scale, including five questions, was developed by Diener26 and translated by Jo and Cha27 to assess overall satisfaction with life. Each item is rated in a seven-point scale ranging from 1, Not at all, to 7, Extremely. The possible total score for satisfaction with life ranges from 5 to 35 points, with a higher level of life satisfaction indicated by a higher score. A previous study showed that the internal reliability coefficient was 0.84.27

Physical examination

A sex hormone test involved testosterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), prolactin, and others.28 The test results may provide useful information for drug treatment. Also, some of these hormones have been used to predict the recidivism rate of sex criminals.29 In addition, some of these hormones may be used to minimize the complications that may be caused by the administration of antiandrogen. A basic physical examination was performed with the subjects; it included the basic assessment of medical history, a blood test, and electrocardiography. For comparison of the effects between before and after treatment, the Clinical Global Impression (CGI)30 was performed. A clinical assessment was performed at each visit by a psychiatrist.

Baseline evaluation and follow-up evaluations

The subjects were injected with 3.6 mg of leuprorelin depot during the hospitalization before discharge, and the subjects were subcutaneously injected with the same drug per month after the discharge. During the probation period, all the patients underwent psychological intervention, such as psychoeducation and supportive therapy. A drug treatment in addition to the injection was performed for one subject, who was given 10 mg of olanzapine daily to treat the comorbidity of delusional disorder.

The PCL-R, SAST, WSFQ, SWLS, Malach Burnout Inventory, Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S), and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) tests were performed at baseline and at 4 weeks and 12 months after the start of the drug administration.

Ethics statement

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University Hospital (2015-12-014-002). A Psychiatrist met with all participants directly to give a full verbal explanation and a short form document with information about the study, including the study's purpose and procedure. We then obtained informed written consent from all participants to voluntarily participate before the study began. For two of them, the self-report questionnaire could not be implemented because they refused the interview. Thus, the final paraphilia offender group included seven patients, excluding these two.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

For the eight offenders included in the present study, the average age was 46.63 ± 9.58 years. They were all patients undergoing GnRH injection treatment by a court order. They showed a mean IQ of 94.14 ± 8.73, an average verbal intelligence quotient (VIQ) of 98.00 ± 8.34, and a mean performance intelligence quotient (PIQ) of 99.40 ± 8.96 (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sexual offenders.

| Variables | No. | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 8 | 46.63 ± 9.58 |

| IQ | 7 | 94.14 ± 8.73 |

| VIQ | 98.00 ± 8.34 | |

| PIQ | 99.40 ± 8.96 |

SD = standard deviation, IQ = intelligence quotient, VIQ = verbal intelligence quotient, PIQ = performance intelligence quotient.

Effects of GnRH

At one month after the injection administration began, the patients reported that they had little sexual desire and dramatically decreased sexual interest, and that the frequency of erection was decreased significantly. The MMPI scores obtained from seven of the eight sex offenders were compared before and after the GnRH injection. The masculinity-femininity (Mf) score was 54.83 ± 3.97 in the baseline state, and 47.33 ± 4.97 at Month 12, indicating that there was a significant difference between the two states (Z = 2.23, P = 0.026) (Table 2).

Table 2. MMPI profile between baseline and 12 months state of sexual offenders.

| MMPI | Baseline (n = 7) | 12 mon (n = 7) | Z | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 57.17 ± 12.95 | 58.67 ± 4.13 | −0.31 | 0.753 |

| F | 47.00 ± 6.90 | 46.50 ± 6.38 | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| K | 55.33 ± 6.56 | 65.67 ± 9.67 | −1.36 | 0.173 |

| Hs | 55.33 ± 11.59 | 59.00 ± 6.75 | −1.47 | 0.141 |

| D | 57.33 ± 13.50 | 51.83 ± 9.09 | −0.94 | 0.345 |

| Hy | 56.83 ± 12.21 | 57.33 ± 7.23 | −0.11 | 0.917 |

| Pd | 60.17 ± 13.47 | 57.50 ± 8.19 | −0.74 | 0.462 |

| Mf | 54.83 ± 3.97 | 47.33 ± 4.97 | −2.23 | 0.026 |

| Pa | 51.17 ± 9.11 | 48.50 ± 7.45 | −0.95 | 0.340 |

| Pt | 52.67 ± 9.22 | 50.50 ± 7.45 | −0.54 | 0.588 |

| Sc | 51.50 ± 8.53 | 49.33 ± 7.99 | −0.94 | 0.345 |

| Ma | 44.17 ± 6.43 | 40.83 ± 8.01 | −1.26 | 0.207 |

| Si | 55.17 ± 12.12 | 47.17 ± 7.08 | −1.36 | 0.173 |

These data represent mean ± standard deviation, ANCOVA adjusted for age, education level by general linear model, significant P value < 0.05.

MMPI = Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, L = lie, F = infrequency, K = defensiveness, Hs = hypochondriasis, D = depression, Hy = hysteria, Pd = psychopathic deviate, Mf = masculinity-femininity, Pa = paranoia, Pt = psychasthenia, Sc = schizophrenia, Ma = hypomania, Si = social introversion.

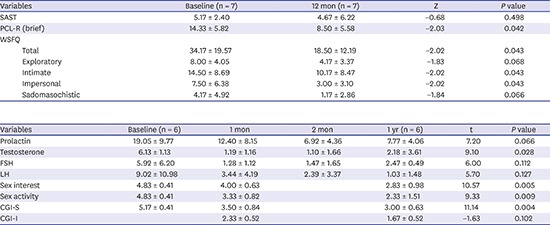

Various psychological assessment scales were used with seven of the sex offenders, and the score was compared between Month 12 state and the baseline state before the GnRH injection. The score for the BIS was 50.00 ± 8.39 in the baseline state and 42.67 ± 8.33 in Month 12 state, indicating that there was a significant difference between the two states (Z = −2.02, P = 0.043). The score for the Quality of Life Scale was 15.33 ± 6.25 in the baseline state and 19.83 ± 8.04 in Month 12 state, indicating that there was a significant difference between the two states (Z = 2.03, P = 0.042) (Table 3). Also, the score for the PCL-R was 14.33 ± 5.82 in the baseline state and 8.50 ± 5.58 in Month 12 state, indicating that there was a significant difference between the two states (Z = −2.03, P = 0.042). The total score for the WSFQ was 34.17 ± 19.57 in the baseline state and 18.50 ± 12.19 in Month 12 state, indicating that there was a significant difference between the two states (Z = 2.02, P = 0.043) (Table 4).

Table 3. Psychological profiles between baseline and 12 months state of sexual offenders.

| Variables | Baseline (n = 7) | 12 mon (n = 7) | Z | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI (depression) | 18.83 ± 12.24 | 13.67 ± 3.88 | −0.95 | 0.343 | |

| CES-D (depression) | 25.80 ± 11.76 | 21.20 ± 11.90 | −0.67 | 0.500 | |

| BAI (anxiety) | 16.17 ± 12.77 | 8.83 ± 3.66 | −0.95 | 0.344 | |

| STAI (anxiety) | 47.50 ± 9.67 | 40.17 ± 7.28 | −1.48 | 0.138 | |

| BSI (suicide idea) | 7.33 ± 9.20 | 3.33 ± 4.46 | −1.84 | 0.066 | |

| MBI (burnout) | 67.80 ± 17.25 | 61.20 ± 9.01 | −0.67 | 0.500 | |

| BIS (impulsivity) | |||||

| Total | 50.00 ± 8.39 | 42.67 ± 8.33 | −2.02 | 0.043 | |

| Cognitive | 13.50 ± 1.38 | 13.17 ± 1.33 | −0.38 | 0.705 | |

| Movement | 17.83 ± 7.28 | 13.83 ± 5.08 | −1.46 | 0.144 | |

| Unplanned | 18.67 ± 3.93 | 15.67 ± 3.61 | −1.89 | 0.058 | |

| QOL (life quality) | 15.33 ± 6.25 | 19.83 ± 8.04 | −2.03 | 0.042 | |

| RSI (self-esteem) | 28.83 ± 6.94 | 30.83 ± 3.43 | −0.81 | 0.416 | |

| K-AADHS (ADHD) | |||||

| Total | 26.00 ± 6.93 | 23.83 ± 5.71 | −1.63 | 0.104 | |

| Inattention | 13.67 ± 3.56 | 12.00 ± 2.61 | −1.46 | 0.144 | |

| Hyperactivity | 12.33 ± 3.56 | 11.83 ± 3.31 | −0.82 | 0.414 | |

These data represent mean ± standard deviation. Nonparametric paired test, significant P value < 0.05.

BDI = Beck's Depression Inventory, CES-D = The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scales Revised, BAI = Beck's Anxiety Inventory, STAI = Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory, SIS = Beck's Suicide Idea Scale, K-AADHS = Korean Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Scales, ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, MBI = Maslach Burnout Inventory, BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, QOL = Quality of Life Scale, RSI = Rosenberg's self-esteem inventory.

Table 4. Sexual desire profile between baseline and 12 months state of sexual offenders.

| Variables | Baseline (n = 7) | 12 mon (n = 7) | Z | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAST | 5.17 ± 2.40 | 4.67 ± 6.22 | −0.68 | 0.498 | |

| PCL-R (brief) | 14.33 ± 5.82 | 8.50 ± 5.58 | −2.03 | 0.042 | |

| WSFQ | |||||

| Total | 34.17 ± 19.57 | 18.50 ± 12.19 | −2.02 | 0.043 | |

| Exploratory | 8.00 ± 4.05 | 4.17 ± 3.37 | −1.83 | 0.068 | |

| Intimate | 14.50 ± 8.69 | 10.17 ± 8.47 | −2.02 | 0.043 | |

| Impersonal | 7.50 ± 6.38 | 3.00 ± 3.10 | −2.02 | 0.043 | |

| Sadomasochistic | 4.17 ± 4.92 | 1.17 ± 2.86 | −1.84 | 0.066 | |

These data represent mean ± standard deviation. Nonparametric paired test, significant P value < 0.05.

SAST = Sexual Addiction Screening Test, PCL-R = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, WSFQ = Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire.

The level of individual sex hormones in six of the sex offenders was assessed at the baseline state, and at Month 1, Month 2, and Month 12 after starting the GnRH injections. The testosterone level was 6.13 ± 1.13 at the baseline state, 1.19 ± 1.16 in Month 1, 1.10 ± 1.66 in Month 2, and 2.18 ± 3.61 in Month 12, and a repeated nonparametric test of the values showed that there was a significant difference (t = 9.10, P = 0.028). The sexual interest, sexual activity, CGI severity, and CGI improvement were assessed with six of the sex offenders at the baseline state, Month 1, and Month 12 after starting the GnRH injections. The sexual interest score was 4.83 ± 0.41 at the baseline state, 4.00 ± 0.63 in Month 1, and 2.83 ± 0.98 in Month 12, and a repeated nonparametric test of the values showed that there was a statistically significant difference (t = 10.57, P = 0.005). Also, the sexual activity score was 4.83 ± 0.41 at the baseline state, 3.33 ± 0.82 in Month 1, and 2.33 ± 1.51 in Month 12, and a repeated nonparametric test of the values showed that there was a statistically significant difference (t = 9.33, P = 0.009). The CGI severity score was 5.17 ± 0.41 at the baseline state, 3.50 ± 0.84 in Month 1, and 3.00 ± 0.63 in Month 12, and a repeated nonparametric test of the values showed that there was a statistically significant difference (t = 11.14, P = 0.004) (Table 5).

Table 5. Laboratory and medical profile between baseline and 12 months state of sexual offenders.

| Variables | Baseline (n = 6) | 1 mon | 2 mon | 1 yr (n = 6) | t | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolactin | 19.05 ± 9.77 | 12.40 ± 8.15 | 6.92 ± 4.36 | 7.77 ± 4.06 | 7.20 | 0.066 |

| Testosterone | 6.13 ± 1.13 | 1.19 ± 1.16 | 1.10 ± 1.66 | 2.18 ± 3.61 | 9.10 | 0.028 |

| FSH | 5.92 ± 6.20 | 1.28 ± 1.12 | 1.47 ± 1.65 | 2.47 ± 0.49 | 6.00 | 0.112 |

| LH | 9.02 ± 10.98 | 3.44 ± 4.19 | 2.39 ± 3.37 | 1.03 ± 1.48 | 5.70 | 0.127 |

| Sex interest | 4.83 ± 0.41 | 4.00 ± 0.63 | 2.83 ± 0.98 | 10.57 | 0.005 | |

| Sex activity | 4.83 ± 0.41 | 3.33 ± 0.82 | 2.33 ± 1.51 | 9.33 | 0.009 | |

| CGI-S | 5.17 ± 0.41 | 3.50 ± 0.84 | 3.00 ± 0.63 | 11.14 | 0.004 | |

| CGI-I | 2.33 ± 0.52 | 1.67 ± 0.52 | −1.63 | 0.102 |

These data represent mean ± standard deviation. Nonparametric paired test, significant P value < 0.05.

FSH = follicle stimulating hormone, LH = Leuteinizing Hormone, CGI-S = Clinical Global Impression-Severity, CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression-Improvement.

Adverse effects

Following the administration of 3.6 mg of leuprorelin depot, the patients reported that erection was possible, but ejaculation was impossible, as a result of an adverse effect of the drug. The masculine appearance of the patients became softer after the administration. No other adverse effect was reported. On the risk of osteoporosis, an orthopedist stated that no abnormality was found in the X-rays of the hand.

The patients in the present study did not complain about the ‘flare up’ phenomenon following the administration of GnRH depot preparation found in a previous study; so no particular drug was administered in parallel.

DISCUSSION

There are various therapeutic methods for treating sexual offenders, such as psychoanalytic psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy (e.g., aversion therapy), surgical castration, and drug treatment for reducing sexual desire. The best treatment method for paraphilia is the combination of cognitive behavioral and drug treatment.31 However, the opinion that punishment with chemical castration treatment is needed for public safety could conflict with the opinion that the most clinically effective therapeutic method needs to be selected.32 Drugs used for the treatment of paraphilia include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), cyproterone acetate, medroxyprogesterone, and GnRH analogues. Among them, GnRH analogues are artificially synthesized agents of natural decapeptide GnRH, which is a hormone produced in the cell bodies of hypothalamic neurons and secreted directly into the hypophyseal portal system. GnRH analogues induce the downregulation of gonadotroph cells, the suppression of progesterone secretion, and the mild suppression of follicle-stimulating hormone.33 GnRH analogues are drugs mostly used as selective medicine for central precocious puberty. GnRH analogues stimulate the GnRH receptors of hypophysis in the initial stage, but later gradually suppress the receptors, consequently downregulating the GnRH receptors and desensitizing hypophyseal responses to GnRH.34 Three representative commercial drugs of GnRH analogues are goserelin, triptorelin, which was recently approved in Europe for the treatment of men with severe sexual abnormality, and leuprorelin acetate (3.75 and 11.25 mg), which is one of the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogue depot agents and has been used as a selective treatment for central precocious puberty. Leuprorelin has clinical effects on obstetric and gynecologic diseases, such as endometriosis, and urologic diseases, like prostate cancer, as well as on precocious puberty. Also, GnRH analogues have recently been reported to have clinical effects on paraphiliacs with abnormal sexual behaviors.35 Few studies have investigated the effects of GnRH agents on paraphiliacs. While studies on the drug treatment of paraphilia have been conducted elsewhere, in Korea until recently only a few reports on the study of short-term clinical effects of GnRH depot agents on paraphilia were available.36 A previous case study5,6 reported that, when triptorelin was administered to six patients with paraphilia for seven years, every abnormal sexual behavior disappeared in five patients. Rösler and Witztum37 administered 3.75 mg of the GnRH agonist triptorelin to 30 patients with paraphilia for 8 to 42 months along with supportive therapy. The average age of the subjects was 32; 25 subjects displayed pedophilia, and five were other unclassified paraphiliacs. A notable improvement was observed in their scores on the abnormal sexual fantasy and desire scale; it decreased from an average of 48 points before the treatment to 5 points after the treatment.

GnRH depot agents are thought to suppress abnormal sexual behavior by directly acting on the central nervous system. In an experiment with male rats, the direct administration of GnRH into the cerebral spinal fluid decreased aggression.38 GnRH depot agents are more effective in reducing testosterone within tissues than cyproterone acetate or medroxyprogesterone acetate agents. The continuous administration of GnRH depot agents can cause side effects. By continuously reducing the secretion of androgen, GnRH agents can cause hypogonadism, manifesting especially as impotence in aged men, and could also decrease testicular volume and body hair. In addition, the administration of GnRH agents could reduce both normal and abnormal sexual desire. The long-term administration of GnRH agents can lead to decreased bone density. Long-term administration of GnRH analogues can induce hepatotoxicity, hypertension, weight gain, and calcium loss. On the other hand, depressive disorder has been reported as a side effect of GnRH agonists. Nevertheless, GnRH analogues are recommended as one of the most effective therapeutic methods for paraphilia.36 Most side effects of hypogonadism are reversible when drug administration is stopped.

In this study, the sexual fantasy, interest, and activity that showed a statistically significant difference between the baseline and Month 12 evaluations were those measured by the WSFQ scales, sexual interest/activity scales, and structured CGI severity. This result is consistent with the results of the previous studies in foreign countries. Also, the PCL-R score for recidivism was decreased at Month 12 time evaluation. We suspect that this decrease in sexual fantasy and interest/activity will result in a decrease in recidivism. In this study also, the BIS, which measured total, showed a statistically significant difference between the baseline evaluation and Month 12 time evaluation. This result is consistent with the results of the previous studies in foreign countries. In this study, Month 12 time evaluation group showed low scores in the QOL, PCL-R, WSFQ, sexual interest/activity, and CGI scales.

During the one-year follow-up, mild or moderate adverse reactions were observed in the six patients. A 45-year-old pedophiliac man who was taking 10 mg of olanzapine daily to treat schizophrenia showed moderate obesity (5–6 kg weight gain), moderate feminization of the body shape, and mild itching. A 50-year-old pedophiliac patient had mild urticaria, mild eczema, a weight gain of 4 kg, and mild dizziness. Mild nausea and mild gastric disturbance arose in a 39-year-old pedophiliac patient. In addition, a 46-year-old paraphiliac with alcohol dependence showed mild feminization of the body shape, feelings of fatigue, and mild hot flushes; while a 33-year-old exhibitionism/frotteurism patient experienced mild headaches and mild feelings of fatigue. A 30-year-old exhibitionist had mild insomnia. No medicine was additionally prescribed for these adverse reactions, which spontaneously disappeared within weeks during which the injections were kept at the same dosage. Exceptionally, the weight gain did not spontaneously decrease, but remained at the same level during the follow-up period.

The present study shows the improvement of paraphilia after the administration of a GnRH analogue, but its results, obtained from only a few subjects, should not be generalized, but should be reconfirmed by conducting a study with many more subjects to observe the clinical effects and adverse effects. In addition, efforts should be made to conduct a long-term, large-scale study elaborately designed for accurate diagnosis and assessment with the consent and voluntary participation of a large number of subjects to reconfirm the clinical effect of GnRH analogues. Above all, not only the clinical effects of GnRH analogues but also their safety should be thoroughly investigated. Despite the several limitations related to the clinical effects and safety, GnRH analogues may be applied as an alternative therapeutic method for sex offenders in addition to the conventional therapeutic methods, if the clinical effects of GnRH analogues have been sufficiently proven.

Paraphilia is a psychiatric disease that is very difficult to treat. However, recently developed therapeutic methods for sex offenders with paraphilia, including GnRH injection, have been reported. This article is the first report in Korea about the clinical effect of GnRH injection verified by a long-term study conducted with seven sex offenders undergoing the treatment by a court order. No recidivism of sex crimes was found among the subjects, and a significant therapeutic effect was found from assessments of sexual fantasies and other symptom. However, a mild adverse effect of the drug was found in the seven sex offenders, who had received GnRH injections for more than one year. These results suggest that GnRH injection may be effective in diminishing the sexual fantasies and improving the attitudes of sex offenders and may thus serve as a therapeutic alternative for reducing the sex-crime recidivism rate. In a previous study, they reported that medication such as sexual impulse control injections did not reduce sexual urges such as pedophilic interest. In this study, sexual urges decreased significantly after injection. Although this may be the effect of injections, it is suspected that sustained supportive psychological treatment may have had some effect.

Future studies should be conducted to assess the pure clinical effects of GnRH injection, by objectively comparing the results of treatment using a sexual-impulse control drug and other sexual-impulse control methods, e.g., electronic ankle bracelets, disclosing personal information, and specific psychological treatment, including cognitive and behavioral therapies, in Korea.

Footnotes

Funding: The present research was conducted by the research fund of Dankook University in 2018.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Lim MH. Data curation: Choi JH, Lee JW, Lee JK, Jang S, Yoo M, Lee DB, Hong JW, Noh IS, Lim MH. Formal analysis: Choi JH, Lee JW, Lee JK, Noh IS, Lim MH. Investigation: Choi JH, Lee JW, Lee JK, Jang S, Yoo M, Lee DB, Hong JW, Noh IS, Lim MH. Methodology: Choi JH, Lee JK, Noh IS, Lim MH. Software: Noh IS, Lim MH. Writing - original draft: Choi JH, Lim MH. Writing - review & editing: Choi JH, Lee JW, Lim MH.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon H, Grubin D. Psychiatric aspects of the assessment and treatment of sex offenders. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(1):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kafka MP, Hennen J. A DSM-IV Axis I comorbidity study of males (n = 120) with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Sex Abuse. 2002;14(4):349–366. doi: 10.1177/107906320201400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunsieth NW, Jr, Nelson EB, Brusman-Lovins LA, Holcomb JL, Beckman D, Welge JA, et al. Psychiatric and legal features of 113 men convicted of sexual offenses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):293–300. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thibaut F, Cordier B, Kuhn JM. Effect of a long-lasting gonadotrophin hormone-releasing hormone agonist in six cases of severe male paraphilia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(6):445–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thibaut F, Cordier B, Kuhn JM. Gonadotrophin hormone releasing hormone agonist in cases of severe paraphilia: a lifetime treatment? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21(4):411–419. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(96)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JS. Clinical interpretation of Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. Seoul: Seoul National University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hare RD, Forth AE, Strachan KE. Psychopathy and crime across the lifespan. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, Quinsey VL, editors. Aggression and Violence across the Lifespan. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1992. pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnes P. Sexual addiction screening test. Tenn Nurse. 1991;54(3):29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall LE, Briken P. Assessment, diagnosis, and management of hypersexual disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(6):570–573. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833d15d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson GD. Measurement of sex fantasy. Sex Marital Ther. 1988;3(1):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plaud JJ, Bigwood SJ. A multivariate analysis of the sexual fantasy themes of college men. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23(3):221–230. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YH, Song JY. A study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1991;10(1):98–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997;16(1):185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Kwon JH. Validation for the beck scale for suicide ideation with korean university students. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2009;28(4):1155–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslach C. Burnout: the Cost of Caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang JH, Kim CW. Evaluating applicability of maslach burnout inventory among university hospitals nurses. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2012;24(1):31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barratt ES, White R. Impulsiveness and anxiety related to medical students' performance and attitudes. J Med Educ. 1969;44(7):604–607. doi: 10.1097/00001888-196907000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H. Impulsivity Test. Seoul: Korean Guidance; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YH. The Relations between attributional style, life events, event attribution, hopelessness and depression [dissertation] Seoul: Seoul National University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo J, Yang W, Lee K, Lee S, Lee CS, Lee HY, et al. Gender difference in self-esteem of medical students. Korean J Med Educ. 2003;15(3):241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim EJ. The validation of Korean Adult ADHD Scale (K-AADHDS) Korean J Clin Psychol. 2003;22(4):897–911. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jo MH, Cha KH. Comparison of Quality of Life between Countries. Seoul: Jipmundang; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bourget D, Bradford JM. Evidential basis for the assessment and treatment of sex offenders. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2008;8(1):130–146. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingston DA, Seto MC, Ahmed AG, Fedoroff P, Firestone P, Bradford JM. The role of central and peripheral hormones in sexual and violent recidivism in sex offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(4):476–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rev. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thibaut F, De La Barra F, Gordon H, Cosyns P, Bradford JM WFSBP Task Force on Sexual Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):604–655. doi: 10.3109/15622971003671628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward T, Gannon TA, Birgden A. Human rights and the treatment of sex offenders. Sex Abuse. 2007;19(3):195–216. doi: 10.1177/107906320701900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conn PM, Crowley WF., Jr Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and its analogues. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(2):93–103. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101103240205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheeler MD, Styne DM. Drug treatment in precocious puberty. Drugs. 1991;41(5):717–728. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199141050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson WF, McNeill E, Reid S, Hollman AS, Donaldson MD. Efficacy of Zoladex LA (goserelin) in the treatment of girls with central precocious or early puberty. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79(4):323–327. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.4.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HS, Park WS, Lee JW, Lim MH. A case of an adolescent with paraphilia with depot GnRH analogue (goserelin) Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2011;22(4):230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rösler A, Witztum E. Treatment of men with paraphilia with a long-acting analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):416–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kádár T, Telegdy G, Schally AV. Behavioral effects of centrally administered LH-RH agonist in rats. Physiol Behav. 1992;51(3):601–605. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]