Gentamicin is a common antibiotic used in neonates and infants. A recently published population pharmacokinetic (PK) model was developed using data from multiple studies, and the objective of our analyses was to evaluate the feasibility of using a national electronic health record (EHR) database for further external evaluation of this model.

KEYWORDS: EHR, external evaluation, gentamicin, infant, pharmacokinetics, pediatrics

ABSTRACT

Gentamicin is a common antibiotic used in neonates and infants. A recently published population pharmacokinetic (PK) model was developed using data from multiple studies, and the objective of our analyses was to evaluate the feasibility of using a national electronic health record (EHR) database for further external evaluation of this model. Our results suggest that, with proper data capture procedures, EHR data can serve as a potential data source for external evaluation of PK models.

TEXT

Gentamicin is one of the most commonly used antibiotics prescribed for treatment of or prophylaxis against Gram-negative infections in infants (1–3). Nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity are major adverse reactions that are associated with supratherapeutic gentamicin concentrations (4). Due to its narrow therapeutic index and wide pharmacokinetic (PK) variability, therapeutic drug monitoring of gentamicin is required (5, 6). Target peak concentrations of gentamicin should range from 4 to 10 mg/liter (conventional dosing), and trough levels should be <2 mg/liter (7).

Gentamicin population PK models were developed for infants in previous studies. Both two-compartment and three-compartment models were used to characterize the disposition of gentamicin in infants (8–12). Since gentamicin is almost entirely renally eliminated, age, weight, and serum creatinine (SCR) concentrations were commonly identified as important covariates of gentamicin clearance. Those studies either did not perform external evaluations or performed evaluations using external data sets consisting of 70 to ∼160 subjects (7–11).

Unlike traditional clinical trials, which are challenging to perform with children due to ethical, logistical, and financial factors (13), electronic health records (EHRs) allow researchers to access large volumes of clinical data easily and efficiently. The large sample size and widely distributed profiles in EHRs make them an ideal data source for evaluation of PK models. In previous studies, EHR data were used to develop PK models or to assess the relationship between drug exposure and safety (14, 15). To date, however, we are not aware of any studies that have used a national EHR database for external evaluation of a population PK model. The objective of this study was to use gentamicin as a case study to explore the potential use of EHR data in the evaluation of population PK models.

In this study, EHR data from 348 Pediatrix Medical Group neonatal intensive care units, from 1997 to 2014, were used to evaluate a previously reported gentamicin population PK model. Information in the EHRs included age, weight, sex, dose records, SCR concentrations, and peak and trough plasma concentrations of gentamicin. The population PK model developed by Germovsek et al. (8) is a three-compartment model with weight, postmenstrual age (PMA) and postnatal age (PNA), and SCR concentrations as covariates of clearance. The model was developed on the basis of 1,325 gentamicin serum concentration measurements from 205 infants and was evaluated using 483 gentamicin serum concentration measurements from 163 infants (8).

The following assumptions and criteria were used to extract relevant and reliable EHR data: (i) only infants receiving intravenous injections were included; (ii) the infusion time was assumed to be 30 min; (iii) only concentrations ranging from 4 to 20 mg/liter (peak) and from 0.3 to 10 mg/liter (trough) were included; (iv) peak samples were assumed to be collected 1 h after dosing and trough samples 2 min before dosing; (v) observations recorded from infants with SCR concentrations of >10 mg/dl were excluded; (vi) infants with PNA of >60 days and gestational age (GA) of <23 weeks were excluded; (vii) observations with doses of >6 mg/kg/day were excluded; (viii) to avoid model misspecification caused by data entry errors during regimen switches, only observations recorded during the first dosing regimen were included; and (ix) an occasion was defined as a dose with subsequently obtained gentamicin samples. These assumptions and criteria were based on common clinical practice and infant demographics in the model-building data set. A summary of demographics and dosing for the model-building data set (8) and filtered EHR data is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Population demographics for model-building and EHR dataa

| Data set | No. of participants | No. of measurements | GA (median [range]) (wk) | PNA (median [range]) (days) | Body weight (median [range]) (kg) | Dose (median [range]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-building data setb | 205 | 1,325 | 34 (23.3–42.1) | 5.4 (1–66) | 2.12 (0.53–5.05) | Initial dose of 2–3 mg/kg (twice daily) or 4 mg/kg (every 24 h) |

| EHR data | 4,519 | 6,753 | 29 (23–42) | 1 (1–59) | 1.26 (0.31–4.79) | 3.50 mg/kg/day (0.49–6.00 mg/kg/day) |

GA, gestational age; PNA, postnatal age.

From reference 8.

To assess the predictive performance of the model, plots of population predicted concentrations versus observations for peak and trough concentrations were generated. Parameters were fixed to the final estimates reported in the original publication. The relationships between relevant covariates, i.e., body weight (WT) (in kilograms), measured SCR concentration (MSCR) (in micromoles per liter), typical SCR concentration (TSCR) (in micromoles per liter) (equal to −2.849·PMA [in weeks] + 166.48), PMA (in weeks), and PNA (in days), and PK parameters are described as follows: CL (in liters per hour) = 6.2 × PMA3.33/(PMA3.33 + 55.43.33) × (WT/70)0.632 × (MSCR/TSCR)−0.13 × [PNA/(1.70 + PNA)], V1 (in liters) = 26.5 × (WT/70), V2 (in liters) = 21.2 × (WT/70), V3 (in liters) = 147.9 × (WT/70), Q1 (in liters per hour) = 2.2 × (WT/70)0.75, and Q2 (in liters per hour) = 0.3 × (WT/70)0.75, where CL is clearance, V is volume of distribution, and Q is intercompartmental clearance. Analyses were performed using NONMEM (version 7.3; Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA); the first-order conditional estimation method with interaction was used. Data manipulation was performed with R (version 3.3.2) and RStudio (version 1.0.136). The xpose4 and lattice packages in R and RStudio were used for data visualization (16–18). Visual predictive checks (VPCs) were performed on the basis of 1,000 simulations, using Perl-speaks-NONMEM (version 4.6.0). The bias and precision of the model were evaluated by calculating the jth prediction error (PEj) and relative prediction error (RPEj), the mean prediction error (MPE), and the mean absolute prediction error (MAPE) (equations 1 to 4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

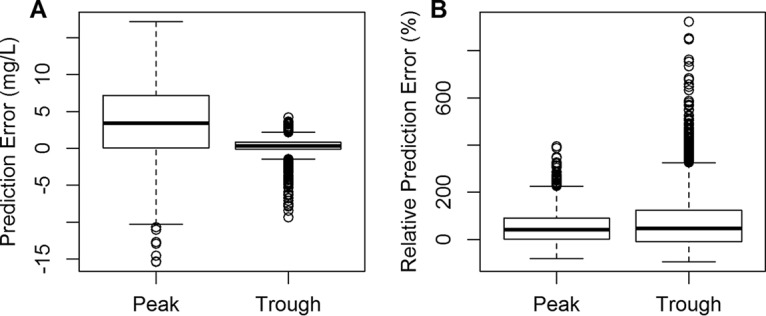

Filtered EHR data contained 6,753 measurements, including 2,580 peak concentrations and 4,173 trough concentrations, from 4,519 infants. The EHR population had a similar age range, compared to the model-building data set (Table 1). Figure 1 shows box plots of the prediction errors and relative prediction errors for peak and trough concentrations. In the VPC plot (Fig. 2), 27.7% of observations were below the 80% prediction interval and 8.2% were above. There was a trend toward gentamicin concentrations plateauing after 24 h (Fig. 2), which might be related to large variations in gentamicin trough concentrations due to the timing of sample collection and different degrees of renal dysfunction among the infants. The median prediction errors were 3.43 mg/liter (2.5th to 97.5th percentile range, −6.20 to 12.95 mg/liter) and 0.35 mg/liter (2.5th to 97.5th percentile range, −2.03 to 1.78 mg/liter) for peak and trough concentrations, respectively. The median relative prediction errors were 40.82% (2.5th to 97.5th percentile range, −49.72 to 213.55%) and 47.14% (2.5th to 97.5th percentile range, −73.22 to 344.92%) for peak and trough concentrations, respectively (negative values indicate underprediction of concentrations). The MPEs from predictions of peak and trough concentrations were 51.0% and 71.0%, respectively. The precision values (measured as MAPEs) for peak and trough concentrations were 62.9% and 92.3%, respectively.

FIG 1.

Box plots of prediction errors (A) and relative prediction errors (B) for peak and trough concentrations. The bottom and top of the box are the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and the thick line in the middle of the box is the 50th percentile. The height of the box is the interquartile range (IQR). The upper whisker indicates the 75th percentile + 1.5·IQR, and the lower whisker indicates the 25th percentile − 1.5·IQR. Open circles are outlier points that are outside 1.5·IQR above the upper quartile and below the lower quartile.

FIG 2.

VPC plot of gentamicin concentrations versus time after the last dose. The shaded regions denote the 95% confidence intervals around the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of simulated concentrations. The dashed lines represent the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles for the observed data. The solid lines represent the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles for the predicted data. Open circles indicate the observed values.

Our results demonstrated that the model developed by Germovsek et al. (8) successfully captured the central tendency of the gentamicin concentrations in the EHR database (Fig. 2), with some notable overprediction (i.e., the distribution of relative prediction errors was skewed to the right) of peak and trough concentrations (Fig. 1). Peak concentrations were predicted with greater accuracy and precision, compared to trough concentrations, which is consistent with the findings from the original analysis. Overall, the model appears to have less accuracy and precision when evaluated with the EHR data, compared to the initial external database (8); this may be explained by assumptions we made in modeling the EHR data, particularly the lack of exact sampling times, which might lead to misspecification. There are variations in clinical practice regarding when peak concentrations are obtained, and a significant number of samples being drawn 1 h, rather than 30 min, after dosing might lead to overprediction of gentamicin concentrations. Additionally, differences in the gentamicin assays used by the centers might introduce measurement error, especially for trough concentrations falling near the lower limit of quantification. Since therapeutic hypothermia is associated with alterations in gentamicin PK and we could not capture this from the current data set, this factor may explain some of the observed misspecification (19). Therefore, it is likely that the model misspecification we observed in our analyses is related to the assumptions we made in developing our gentamicin EHR database for external evaluation. Given that this model performed well in previous external evaluations (8), further study focused on clinical implementation and evaluation of this model's use in facilitating dose individualization is justified.

While the use of EHR databases can significantly enhance the quantity of clinical data, ensuring that the data are of high quality is still crucially important. The major challenge we encountered in performing population PK modeling of EHR data was the lack of accurate documentation of sampling times and appropriate formatting of clinical data, which required us to apply reasonable assumptions to estimate missing information, as well as necessitating significant effort to prepare analysis-ready data sets. As a result, the misspecification we identified might result from either model error or data inaccuracy, which makes the evaluation of PK models more challenging. To maximize the use of EHR data in building and evaluating population PK models, more studies are needed to identify efficient procedures for extraction of large volumes of accurate clinical data from EHR databases. In addition, the widespread use of EHR databases in model evaluations could benefit from improvements in the protocols for clinical data collection, particularly the timing of dosing and PK measurements.

In conclusion, a national EHR database was used for external evaluation of a published population PK model for gentamicin in infants. Despite notable misspecifications, the model captured the central tendency of the gentamicin concentrations in the EHR database. Improvements in EHR data collection are required to maximize the robustness of EHR databases for population PK model evaluations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jaimit Parikh for his contribution to data set preparation.

R.J.B. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant T32GM086330). C.P.H. receives salary support for research from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (K23HD090239) and the U.S. government for his work in pediatric and neonatal clinical pharmacology (government contract HHSN267200700051C; principal investigator: Daniel K. Benjamin, Jr., under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act) and other sponsors (Eli Lilly and Company, Purdue Pharma L.P.) for drug development in adults and children (www.dcri.duke.edu/research/coi.jsp). K.Z. receives support from the NICHD (grants HHSN275201000003I and K23HD091398) and the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Awards (grant KL2TR001115). M.C.-W. receives support from the NIH (grant 1R01-HD076676-01A1), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (grant UL1TR001117), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (grants HHSN272201500006I and HHSN272201300017I), the NICHD (grant HHSN275201000003I), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (grant 1U01FD004858-01), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (grant HHSO100201300009C), the Thrasher Research Fund, CardioDx, and Durata Therapeutics. M.M.L. receives support from the FDA (grant R01FD005101), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (grant 1R34HL124038), and the NICHD Pediatric Trials Network (contract HHSN267200700051C). D.G. receives support from the NICHD (grant K23HD083465). The remaining authors have no funding to disclose.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chattopadhyay B. 2002. Newborns and gentamicin: how much and how often? J Antimicrob Chemother 49:13–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha MJ, Almeida AM, Afonso E, Martins V, Santos J, Leitão F, Falcão AC. 2000. The kinetic profile of gentamicin in premature neonates. J Pharm Pharmacol 52:1091–1097. doi: 10.1211/0022357001775010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glover ML, Shaffer CL, Rubino CM, Cuthrell C, Schoening S, Cole E, Potter D, Ransom JL, Gal P. 2001. A multicenter evaluation of gentamicin therapy in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pharmacotherapy 21:7–10. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.1.7.34441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begg EJ, Barclay ML. 1995. Aminoglycosides: 50 years on. Br J Clin Pharmacol 39:597–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touw DJ, Westerman EM, Sprij AJ. 2009. Therapeutic drug monitoring of aminoglycosides in neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet 48:71–88. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Lent-Evers NAEM, Mathôt RAA, Geus WP, Van Hout BA, Vinks AATMM. 1999. Impact of goal-oriented and model-based clinical pharmacokinetic dosing of aminoglycosides on clinical outcome: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ther Drug Monit 21:63–73. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers H. 2006. The aminoglycosides, p 1155–1171. In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (ed), Goodman & Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th ed McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Germovsek E, Kent A, Metsvaht T, Lutsar I, Klein N, Turner MA, Sharland M, Nielsen EI, Heath PT, Standing JF. 2016. Development and evaluation of a gentamicin pharmacokinetic model that facilitates opportunistic gentamicin therapeutic drug monitoring in neonates and infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4869–4877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00577-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen EI, Sandström M, Honore PH, Ewald U, Friberg LE. 2009. Developmental pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in preterm and term neonates: population modelling of a prospective study. Clin Pharmacokinet 48:253–263. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García B, Barcia E, Pérez F, Molina IT. 2006. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in premature newborns. J Antimicrob Chemother 58:372–379. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs A, Guidi M, Giannoni E, Werner D, Buclin T, Widmer N, Csajka C. 2014. Population pharmacokinetic study of gentamicin in a large cohort of premature and term neonates. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78:1090–1101. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medellín-Garibay SE, Rueda-Naharro A, Peña-Cabia S, Garcí B, Romano-Moreno S, Barcia E. 2015. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin and dosing optimization for infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:482–489. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03464-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field MJ, Behrman RE (ed). 2004. Ethical conduct of clinical research involving children, p 58–92. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. doi: 10.17226/10958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman KO, Wu H, Greenberg R, Guptill JT, Hill K, Patel UD, Ku L, Gonzalez D, Hornik C, Jiang W, Zheng N, Melloni C, Cohen-Wolkowiez M. 2016. Therapeutic drug monitoring, electronic health records, and pharmacokinetic modeling to evaluate sirolimus drug exposure-response relationships in renal transplant patients. Ther Drug Monit 38:600–606. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salerno S, Hornik CP, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Smith PB, Ku LC, Kelly MS, Clark R, Gonzalez D. 2017. Use of population pharmacokinetics and electronic health records to assess piperacillin-tazobactam safety in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 36:855–859. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar D, Andrews F. 2016. latticeExtra: extra graphical utilities based on lattice. https://rdrr.io/rforge/latticeExtra.

- 17.Sarkar D. 2008. Lattice multivariate data visualization with R. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. 1999. Xpose: an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 58:51–64. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2607(98)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mark LF, Solomon A, Northington FJ, Lee CKK. 2013. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Ther Drug Monit 35:217–222. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3182834335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]