Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a complex disease with a growing incidence worldwide. HF is accompanied by a wide range of conditions which affect disease progression, functional performance and contribute to growing healthcare costs. The interactions between a failing myocardium and altered cerebral functions contribute to the symptoms experienced by patients with HF, affecting many comorbidities and causing a poor prognosis. This article provides a condensed version of the 2018 position paper from the Study Group on Heart and Brain Interaction of the Heart Failure Association. It addresses the reciprocal impact on HF of several pathological brain conditions, including acute and chronic low perfusion of the brain, and impairment of higher cortical and brain stem functions. Treatment-related interactions – medical, interventional and device-related – are also discussed.

Keywords: Heart failure, neuro-cardiac reflexes, cerebral perfusion, cognitive impairment

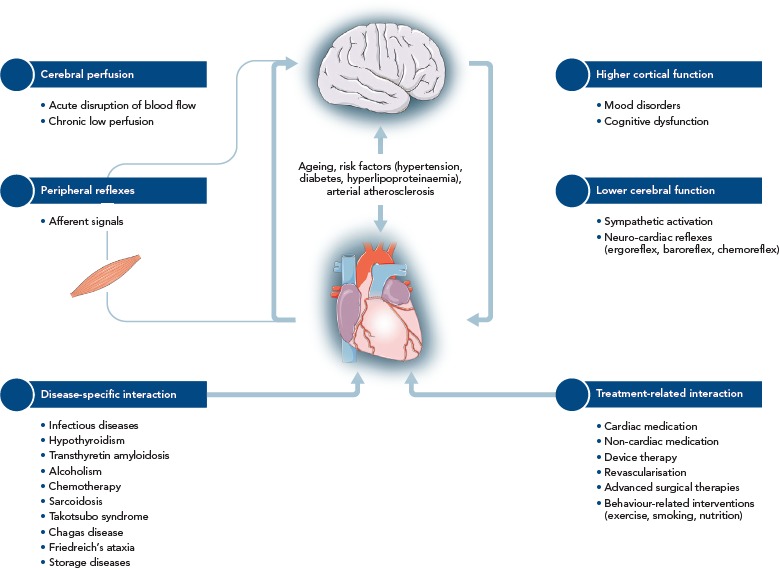

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome with more than 15 million diagnosed cases worldwide.[1,2] Characterised by structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection fraction (EF)[3], HF is frequently accompanied by multiple comorbidities. Brain disorders, including stroke, mental disturbances and cognitive impairment are distinct from the comorbidities traditionally related to HF and require specific management. Both organs are linked by multiple feedback signals, and the discovery of bi-directional interactions of failing heart and neuronal signals has led to the concept of the cardio-cerebral syndrome in HF.[4] This article provides a condensed version of the recently published position paper from the Study Group on Heart and Brain Interaction of the Heart Failure Association and details several pathophysiological and functional aspects of the heart–brain interactions in HF (Figure 1).[5]

Figure 1: Heart and Brain Interactions in Heart Failure.

Source: Doehner, et al., 2018.5 Used with permission from Wiley.

Stroke and Cerebral Perfusion in Patients with Heart Failure

Stroke is one of the leading causes of mortality and disability in adult life and had a global incidence rate of more than 10 million in 2013.[6,7] Patients with HF have an increased risk for stroke,[8] and it contributes to morbidity and mortality in this patient group.[9] In the population-based Framingham Heart Study, the relative risk of stroke in people with HF was four-fold higher for men and three-fold higher for women compared with patients without HF.[8] The prevalence of stroke did not differ between patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HEpEF) and those with HF with restricted ejection fraction (HFrEF) and ranged between 2.4 and 5.8 % for HFrEF and between 3.8 and 7.4 % for HFpEF in clinical trials.[10–12] This overall reduction in risk may be related to the treatment of the disease and initiation of stroke prevention measures.

Several risk factors for stroke in patients with HF have been established. A hypercoagulable state, with activated coagulation and disturbances in proteolytic systems,[13] reduced blood flow, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, has been implicated in the development of systemic cardioembolic events in HF including stroke. Further factors such as low flow patterns due to an enlarged left atrium[14] or reduced contractility of the left ventricle (LV) with apical akinesia or aneurysm represent additional risk factors of intracardiac thrombosis and, consequently, embolic stroke in patients with HF.[15,16] Incidence reported in 10 small-scale observational case-control studies show wide variations in the incidence of thrombo-embolic events with a range of 1.4–12.5 % in HF patients including those with atrial fibrillation (AFib) and those receiving oral anticoagulation therapy.[17]

Further risk factors such as small vessel disease and large artery atherosclerosis are common in people with ischaemic HF.[18] In patients with carotid artery stenosis, reduction of perfusion pressure due to systolic HF may result in a greater volume of ischaemic lesion.[19] In addition, a cerebral lesion may remain clinically undetected as a so-called “silent” infarction. The prevalence of silent cerebral infarctions is comparably high in HF cohorts ranging between 27 and 63 %,[20,21] which is higher than in age-matched subjects without HF.[22] Silent cerebral infarctions and other structural brain damages, such as increased white matter hyperintensities[24] or grey matter loss,[24] are frequently found in imaging tests for HF patients with cognitive dysfunction and dementia.[25]

While the benefit of antithrombotic therapy in the context of AFib is clearly established regardless of the presence of HF, there is no adequate antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in HF patients with maintained sinus rhythm. The Warfarin versus Aspirin in Patients with Reduced Cardiac Ejection Fraction (WARCEF) trial revealed no overall difference between warfarin and aspirin in preventing ischaemic stroke in HF patients with a mean reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 24.7 % (±7.5) and sinus rhythm.[26] A reduced risk of ischaemic stroke after warfarin was equalised by the increased risk of major bleeding. A borderline significant benefit of warfarin on the primary outcome (ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke or death from any cause) was observed only after 4 years. The analysis of two smaller randomised controlled trials, the Heart Failure Long-term Antithrombotic Study (HELAS)[27] and Warfarin/Aspirin Study of Heart Failure (WASH),[28] demonstrated no benefit for patients with HF having antithrombotic therapy compared with placebo regarding vascular events and mortality.[29] Accordingly, a position paper from a European Society of Cardiology working group does not support the routine use of warfarin in patients with HF and sustained sinus rhythm.[17] It should be noted, however, that the risk–benefit ratio might be significantly improved with the introduction of novel anticoagulant (NOAC) therapies, and the results from the WARCEF trial may be outdated.

While stroke represents an acute case of low cerebral perfusion, chronic low cerebral perfusion may manifest in a series of structural cerebral alterations of grey and white matter damage in HF patients.[30,31] Vascular auto-regulation of the cerebral vasculature (the Bayliss effect) enables maintenance of normal perfusion even with severely elevated blood pressure and it protects the brain against blood pressure peaks. Regional hypoperfusion may occur at low perfusion pressures, and chronic low perfusion may account for metabolic impairment, structural decrease and eventual functional decline of brain areas involved in autonomic, neuropsychological and cognitive control.[32] Regional vascular recruitment is modulated by functional activity and local oxygen demands and is locally controlled by a range of factors addressed by the ‘neurovascular unit’, a heterogeneous structure composed of different cell types including astrocytes, pericytes, endothelial cells of the blood brain barrier, microglia and neurons.[33]

Regional hypoperfusion has been observed in multiple brain areas in people with HF, largely lateralised towards the right side in the occipital, temporal, frontal and parietal regions.[34] Bilateral areas of reduced blood flow were observed in the prefrontal cortex, frontal white matter, anterior corpus callosum, thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and occipital cortex. The decreased regional perfusion may contribute to the autonomic, mood and cognitive regulatory deficits observed in HF. Further, impaired perfusion of multiple brain areas involved in the control of vision, language and speech have been observed that could explain the respective deficits in HF patients.[34]

Higher Cortical Function in Patients with Heart Failure

There are two patterns of cognitive problems in HF that are recognised in clinical practice: a chronic, progressive decline in cognitive ability and an acute change in cognition associated with decompensated HF. Cognitive decline in executive function, attention, episodic memory, language, psychomotor speed and visuospatial ability is typical for patients with HF, with differences between HFrEF and HFpEF.[35,36] Accelerated cognitive decline may result from chronic hypoperfusion over the long-term course of HF. The prevalence of early-onset cognitive impairment ranging from 25–74 % has been observed in patients with HF, and is associated with early death, loss of functional independence, worse adherence to therapy and decreased quality of life.[37,38,39,40]

Delirium, a common sequela of decompensated HF, is associated with prolonged hospital stays and increased mortality.[41] Despite its high rate and severe clinical impact, the relationship between acute delirium and HF has not been studied in detail. Cognitive decline is also observed in patients with acute decompensating HF (ADHF), and one study has shown that cognitive performance with respect to memory, perceptual speed, and executive control was affected more severely in 20 patients with ADHF compared with 20 patients with stable chronic HF.[42] Another clinical trial demonstrated that 80 % of 744 patients with ADHF had cognitive impairment in at least one of the cognitive domains, such as processing speed, memory and executive function.[43] A correlation between cognition and markers of haemodynamic performance (left ventricular EF and N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide) as well as inflammation (C-reactive protein) suggests that hypotensive blood pressure and haemodynamic failure plays a role in cognitive impairment.[42]

Mood and anxiety disorders in HF have been investigated in several clinical trials, and depression in patients with HF has become a major focus of research in recent years. Clinical studies have observed that depression is associated with poor quality of life, lower treatment adherence, greater morbidity and mortality, increased hospitalisation and higher healthcare costs for patients with HF.[44,45,46] The aggregated prevalence of depression in patients with chronic HF is 21.5 %[47] compared with 2.3–4.7 % in the general population.[48,49] Elevated prevalence has been linked to more severe functional class and differences were observed between patients with New York Heart Association class 2 and 3 HF. However, data reporting the prevalence of depression are variable because of the use of different assessment methods, the heterogeneity of cohorts and the wide range of depression symptoms.

Anxiety is another frequently encountered disorder in HF patients with a prevalence ranging from 9–53 %.[50] Anxiety in people with HF is related to older age, low level of education, poor socioeconomic status, previous psychiatric disease, decreased quality of life, multiple hospitalisations, increased natriuretic peptide levels and impaired functional capacity.[51] Depression and anxiety appeared as independent predictors of all-cause mortality in a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 1–3 years’ follow-up.[50] Treatment of depression with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for people with HF has not been successful and the results of two major randomised controlled trials (SADHART[52] and MOOD-HF[53]) did not show significant improvement in depression scores and HF outcomes. However, in observational small-scale studies, effective management of HF-related physical symptoms improved anxiety and depression scores significantly.[54] Disease management programmes and aerobic exercise seem to be as effective as drug therapy,[55] and repeated visits from nurses and routine contact calls from healthcare staff to give education and care support were found to reduce hospital readmissions and increase quality of life.[56]

Peripheral Reflexes and Brain Stem Function

The impact of the central nervous system on vegetative control of the cardiovascular system is not fully understood. Cardiovascular signals from chemo-, baro- and ergoreceptors trigger afferent signals to the autonomic nervous system (ANS) control centres that provide efferent sympathetic and parasympathetic signals to form baro-, metabo- or chemoreflex circuits. Imbalanced neuroendocrine activation and control of the myocardium and circulation is fundamental in HF pathophysiology and is a driving force of disease progression and high mortality. Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity characterised by increased sympathetic drive and hyperventilation is predictive of poor outcome in patients with chronic HF.[57] During exercise, the contribution of the muscle ergoreceptors to autonomic, hemodynamic, and respiratory responses among patients with HF has been shown to be enhanced compared with control subjects,[58] leading to hyperventilation and intolerance of exercise.[59] In addition, reduced values of the autonomic markers (heart rate variability and baroreflex sensitivity) were associated with increased mortality after myocardial infarction.[60]

The ANS is an important target for research into HF therapies.[61] Impaired signals between the heart, the cortex and brain stem caused by low perfusion might lead to alterations of the ANS with increased sympathetic tonus, parasympathetic withdrawal and impaired neurocardiac reflexes.[30,32,62] Indeed, regional cerebral blood flow to the frontal cortex fails to rise in HF patients during exercise when compared with healthy controls.[63] Experimental and clinical studies have also shown an association between stroke and increased levels of catecholamines and/or abnormal autonomic control of heart rate (heart rate variability) and arterial baroreflex sensitivity.[64,65] The activation of the sympathetic nervous system, especially after injury involving the insular cortex, promotes the development of AFib, ventricular arrhythmias and abnormalities in QT interval.[66,67] Alterations in blood pressure, heart rate and breathing control that derive from a reduction in baroreflex sensitivity and a concomitant increase in peripheral and central chemosensitivity, lead to a pattern of reflex instability. This pattern, known as Cheyne-Stokes respiration, is observed in advanced HF and manifests as central sleep apnoea. The Adaptive Servo-Ventilation for Central Sleep Apnea in Systolic Heart Failure (SERVE-HF) trial found an increased mortality rate in participants which highlights the importance of this mechanism when central sleep apnoea in patients with advanced HFrEF was treated with adaptive servo-ventilation.[68] The mechanism may be related to the adverse hemodynamic effects of positive airway pressure in HFrEF patients with low EF although the exact mechanism remains uncertain.

Treatment-related Interactions

Treatment-related interactions within the heart–brain axis can be categorised as medical, interventional or device-related. High prevalence of comorbidities in patients with HF accompanied by polypharmacy and age-related pathophysiological changes may affect the efficacy of guideline therapies. Thus, in older patients with HF, the side-effects of lowering blood pressure and the subsequent cerebral hypoperfusion might result in cognitive decline, falls and depression.[69,70] However, hypertension treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of death and admission to hospital in a meta-analysis investigating more than 13,000 patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm.[71]

In patients receiving device therapy, an increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety during the initial weeks after implantation have been shown.[72,73] These symptoms fade, especially in patients who have a favourable response to the therapy, such as cardiac resynchonisation, and cognitive performance improves. Nevertheless, receiving a shock from an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) can lead to emotional dysfunction, anxiety and depression during the following month.[72,73] Almost 20 % of patients with an ICD suffer post-traumatic stress disorder due to a history of cardiac arrest, device implantation and ICD shock, and cognitive behavioural therapy can potentially improve outcomes.[73]

The beneficial effect of exercise on functional status and outcome in patients with HF has been shown in several clinical trials. A wide range of mechanisms, including indirect effects via cerebral signals such as improved sympatho-vagal balance and attenuated activation of ergo- and metaboreflexes, enhancing cerebral haemodynamics, or even cortical, anti-depressive effects of exercise might contribute to physical and functional improvement in patients with HF.[74–76]

Conclusion

HF is a complex clinical syndrome that involves all organs and systems of the body and it is associated with multiple comorbidities. Bi-directional interactions between failing myocardium and brain dysfunction contribute to the symptoms that patients with HF present with and they account for comorbidities such as stroke, impaired ANS functions, sleep apnoea, cognitive impairment or depression. Neuro-cardiac feedback signals significantly promote disease progression and cause a poor prognosis in patients with HF. A better understanding of interactions within the heart–brain axis is needed to improve management and prognosis of HF patients.

References

- 1.Squire I. Socioeconomic status and outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Heart. 2018;104:966–7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogren JA, Fonarow GC, Woo MA. Cerebral impairment in heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11:321–9. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0211-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force writing committee members. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havakuk O, King KS, Grazette L et al. Heart failure-induced brain injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1609–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doehner W, Ural D, Haeusler KG et al. Heart and brain interaction in patients with heart failure: overview and proposal for a taxonomy. A position paper from the Study Group on Heart and Brain Interaction of the Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:199–215. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thrift AG, Thayabaranathan T, Howard G et al. Global stroke statistics. Int J Stroke. 2017;12:13–32. doi: 10.1177/1747493016676285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feigin VL, Mensah GA, Norrving B et al. Atlas of the global burden of stroke (1990–2013): The GBD 2013 Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45:230–6. doi: 10.1159/000441106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Verter J. Manifestations of coronary disease predisposing to stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1983;250:2942–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03340210040022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katsanos AH, Parissis J, Frogoudaki A et al. Heart failure and the risk of ischaemic stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2016;362:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Riet EE, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MA, Rutten FH. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:242–52. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt BJ, Gami AS, Ballman KV et al. The incidence of ischaemic stroke in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Card Fail. 2007;13:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adelborg K, Szépligeti S, Sundbøll J et al. Risk of stroke in patients with heart failure: a population-based 30-year cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48:1161–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafsson C, Blombäck M, Britton M et al. Coagulation factors and the increased risk of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 1990;21:47–51. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.21.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabata T, Oki T, Fukuda N et al. Influence of left atrial pressure on left atrial appendage flow velocity patterns in patients in sinus rhythm. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:857–64. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(96)90478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuadrado-Godia E, Ois A, Roquer J. Heart failure in acute ischaemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6:202–13. doi: 10.2174/157340310791658776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozdag G, Ciftci E, Vural A et al. Silent cerebral infarction in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: echocardiographic correlates. Int J Cardiol. 2006;107:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lip GYH, Ponikowski P, Andreotti F et al. Thrombo-embolism and antithrombotic therapy for heart failure in sinus rhythm. A joint consensus document from the ESC Heart Failure Association and the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:681–95. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haeusler KG, Laufs U, Endres M. Chronic heart failure and ischaemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:2977–82. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.628479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pullicino P, Mifsud V, Wong E et al. Hypoperfusion-related cerebral ischemia and cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;10:178–82. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2001.26870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozdag G, Ciftci E, Ural D et al. Silent cerebral infarction in chronic heart failure: ischaemic and nonischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:463–9. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozdağ G, Yaluğ I, Inan N, Ertaş G, Selekler M, Kutlu H, Kutlu A, Emre E, Çetin M, Ural D. Major depressive disorder in chronic heart failure patients: Does silent cerebral infarction cause major depressive disorder in this patient population? Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2015;43:505–12. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2015.77753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fanning JP, Wong AA, Fraser JF. The epidemiology of silent brain infarction: a systematic review of population-based cohorts. BMC Med. 2014;12:119. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0119-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferson AL, Tate DF, Poppas A et al. Lower cardiac output is associated with greater white matter hyperintensities in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1044–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida OP, Garrido GJ, Etherton-Beer C et al. Brain and mood changes over 2 years in healthy controls and adults with heart failure and ischaemic heart disease. Congest Heart Fail. 2013;15:850–8. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:C3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma S, Thompson JL, Pullicino PM et al. Warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med. 2012;3660:1859–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cokkinos DV, Haralabopoulos GC, Kostis JB et al. Efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in chronic heart failure: the HELAS study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:428–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleland JG, Findlay I, Jafri S. The warfarin/aspririn study in heart failure (WASH: a randomized trial comparing antithrombotic strategies for patients with heart failure. Am J Heart. 148:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lip GY, Shantsila E. Anticoagulation versus placebo for heart failure in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD003336. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003336.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar R, Yadav SK, Palomares JA et al. Reduced regional brain cortical thickness in patients with heart failure. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar R, Woo MA, Macey PM et al. Brain axonal and myelin evaluation in heart failure. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo MA, Kumar R, Macey PM et al. Brain injury in autonomic, emotional, and cognitive regulatory areas in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15:214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalkara T, Alarcon-Martinez L. Cerebral microvascular pericytes and neurogliovascular signaling in health and disease. Brain Res. 2015;1623:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy B, Woo MA, Wang DJ et al. Reduced regional cerebral blood flow in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1294–1302. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Kareken D et al. Cognitive deficits in chronic heart failure. Nurs Res. 2010;59:127–39. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alwerdt J, Edwards JD, Athilingam P et al. Longitudinal differences in cognitive functioning among older adults with and without heart failure. J Aging Health. 2013;25:1358–77. doi: 10.1177/0898264313505111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grubb NR, Simpson C, Fox KA. Memory function in patients with stable, moderate to severe cardiac failure. Am Heart J. 2000;140:E1–5. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogels RL, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alagiakrishnan K, Mah D, Ahmed A, Ezekowitz J. Cognitive decline in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21:661–73. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuccalà G, Pedone C, Cesari M et al. The effects of cognitive impairment on mortality among hospitalized patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2003;115:97–103. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parente D, Luís C, Veiga D et al. Congestive heart failure as a determinant of postoperative delirium. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32:665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kindermann I, Fischer D, Karbach J et al. Cognitive function in patients with decompensated heart failure: the Cognitive Impairment in Heart Failure (CogImpair-HF) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:404–13. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levin SN, Hajduk AM, McManus DD et al. Cognitive status in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Am Heart J. 2014;168:917–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallenborn J, Angermann CE. Comorbid depression in heart failure. Herz. 2013;38:587–96. doi: 10.1007/s00059-013-3886-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramos S, Prata J, Bettencourt P et al. Depression predicts mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a six-years follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jünger J, Schellberg D, Müller-Tasch T et al. Depression increasingly predicts mortality in congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Link SE. Depression in heart failure: a meta analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellervik C, Kvetny J, Christensen KS, Vestergaard M, Bech P. Prevalence of depression, quality of life and antidepressant treatment in the Danish General Suburban Population Study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:507–12. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.877074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Challenging the myth of an “epidemic” of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression between 1990 and 2010. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:506–16. doi: 10.1002/da.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sokoreli I, de Vries JJ, Pauws SC, Steyerberg EW. Depression and anxiety as predictors of mortality among heart failure patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21:49–63. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aggelopoulou Z, Fotos NV, Chatziefstratiou AA et al. The level of anxiety, depression and quality of life among patients with heart failure in Greece. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;34:52–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Setraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:692–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Störk S et al. Effect of Escitalopram on all-cause mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and depression: The MOOD-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2683–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yost G, Bhat G, Mahoney E, Tatooles A. Reduced anxiety and depression in patients with advanced heart failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:406–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Isaksen K, Munk PS, Giske R, Larsen AI. Effects of aerobic interval training on measures of anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with ischaemic heart failure and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: A prospective non-randomized trial. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:300–6. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Matsuo H, Kakinoki S. Home-based disease management program to improve psychological status in patients with heart failure in Japan. Circ J. 2013;77:926–33. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ponikowski P, Chua TP, Anker SD et al. Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity: an ominous sign in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:544–9. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piepoli M, Clark AL, Volterrani M et al. Contribution of muscle afferents to the hemodynamic, autonomic, and ventilatory responses to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: effects of physical training. Circulation. 1996;93:940–52. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ponikowski PP, Chua TP, Francis DP et al. Muscle ergoreceptor overactivity reflects deterioration in clinical status and cardiorespiratory reflex control in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2324–30. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.098491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1998;351:478–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Bilsen M, Patel HC, Bauersachs J et al. The autonomic nervous system as a therapeutic target in heart failure. A scientific position statement from the Translational Research Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1361–78. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woo MA, Macey PM, Keens PT et al. Functional abnormalities in brain areas that mediate autonomic nervous system control in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:437–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosen SD, Murphy K, Leff AP et al. Is central nervous system processing altered in patients with heart failure? Eur Heart J. 2004;25:952–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barber M, Morton JJ, Macfarlane PW et al. Elevated troponin levels are associated with sympathoadrenal activation in acute ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:260–6. doi: 10.1159/000098325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sykora M, Diedler J, Turcani P et al. Baroreflex: a new therapeutic target in human stroke? Stroke. 2009;40:e67–82. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.565838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abboud H, Berroir S, Labreuche J et al. Insular involvement in brain infarction increases risk for cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:691–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lederman YS, Balucani C, Lazar J et al. Relationship between QT interval dispersion in acute stroke and stroke prognosis: a systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2467–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1095–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khachaturian AS, Zandi PP, Lyketsos CG et al. Antihypertensive medication use and incident Alzheimer disease: the Cache country study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:686–92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.noc60013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zuccalà G, Onder G, Pedone C et al. Hypotension and cognitive impairment: selective association in patients with heart failure. Neurology. 2001;57:1986–92. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.11.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koetcha D, Manzano L, Krum H et al. Effect of age and sex on efficacy and tolerability of beta blockers in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: individual patient data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;353:i1855. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Versteeg H, Timmermans I, Meine M et al. Prevalence and risk markers of early psychological distress after ICD implantation in the European REMOTE-CIED study cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2017;240:208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ford J, Rosman L, Wuensch K et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of posttraumatic stress in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29:388–92. doi: 10.1002/jts.22111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Antunes-Correa LM, Nobre TS, Groehs RV et al. Molecular basis for the improvement in muscle metaboreflex and mechanoreflex control in exercise-trained humans with chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1655–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00136.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fu TC, Wang CH, Lin PS et al. Aerobic interval training improves oxygen uptake efficiency by enhancing cerebral and muscular hemodynamics in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tu RH, Zeng ZY, Zhong GQ et al. Effects of exercise training on depression in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:749–57. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]