Abstract

In 2012, a federal court of appeals struck down an FDA rule requiring graphic health warnings on cigarettes as violating First Amendment commercial speech protections. Tobacco product inserts and onserts can more readily avoid First Amendment constraints while delivering more extensive information to tobacco users, and can work effectively to support and encourage smoking cessation. This paper examines FDA’s authority to require effective inserts and onserts and shows how FDA could design and support them to avoid First Amendment problems. Through this process, the paper offers helpful insights regarding how key Tobacco Control Act provisions can and should be interpreted and applied to follow and promote the statute’s purposes and objectives. The paper’s rigorous analysis of existing First Amendment case law relating to compelled commercial speech also provides useful guidance for any government efforts either to compel product disclosures or to require government messaging in or on commercial products or their advertising, whether done for remedial, purely informational, or behavior modification purposes.

On June 22, 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (“Tobacco Control Act”) became law, specifically directing the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to issue regulations requiring graphic health warnings on all cigarette packs by June 22, 2011,2 which FDA did on that same date.3 Members of the tobacco industry challenged the new rule in court, and the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the rule as violating First Amendment protections for commercial speech.4 Since then, FDA has supported significant new research regarding graphic health warnings, but has not yet taken any other publicly visible action to develop or implement any new rule requiring warning labels for cigarettes or any other disclosure of information through cigarette packaging or labels. FDA’s May 2016 final “deeming” rule requires only text-based warnings (no graphics) on the tobacco products it put under the agency’s active tobacco control jurisdiction for the first time (e.g., e-cigarettes, cigars, hookah).5

At some point, FDA will likely issue a legally viable final rule that requires either graphic health warnings or new, stronger text-only warnings on all cigarette packs. However, the amount of information any new warnings could provide consumers would be quite limited because of the relatively small size of the packs – and similar limitations apply to warning labels on the packaging of most other tobacco products. To provide more extensive information directly to tobacco product users, governments could communicate through small printed leaflets either placed inside the product package (“inserts”) or temporarily attached to the outside of the product packaging (“onserts”). For example, inserts and onserts are used with prescription and over-the-counter drugs to provide health warnings, instructions for use, and other information directed at making sure consumers understand the related health risks and use the products as effectively, safely, and beneficially as possible. For quite different purposes, the tobacco companies have used inserts and onserts with their products in the form of coupons, collectable cards, and other promotional materials for over 100 years.6

To date, however, Canada is the only country or other major jurisdiction that has adopted an insert or onsert strategy as part of its tobacco control regulations, requiring cigarette pack inserts with cessation messaging since 2001. Studies of the Canadian inserts provide further evidence that inserts and onserts can work independently, or in conjunction with warnings on tobacco product labels, to help consumers make more informed decisions about their tobacco product use or to promote other public health objectives.7 Indeed, inserts and onserts provide an effective way to reach users of different types of tobacco products with relevant information each time they first handle or open the package of each tobacco product they use. Although users might not read them every time, tobacco product inserts and onserts offer a regularly available resource users can consult whenever motivated to do so, and each time an insert or onsert is seen, even if discarded unread, it provides a physical and visual reminder of its contents.8

FDA appears to have all the statutory authority it needs to establish effective inserts and onserts for different types of tobacco products. The Tobacco Control Act gives FDA extensive authority to regulate tobacco products, including their packaging and labeling, to protect the public health, and also provides FDA with separate, additional authority to regulate tobacco products to educate consumers about tobacco product harms and constituents (some of which specifically mention inserts). But it is not yet clear how FDA will interpret and apply its Tobacco Control Act authorities or the related specific provisions. Nor is it clear how the courts will interpret those provisions when FDA uses them to implement new regulations that will almost certainly face legal challenges from members of the tobacco industry.

Because product onserts can be removed from the outside of the package and inserts are not even seen by consumers until after purchase, they interfere with the communicative aspects of tobacco product packaging much less than warnings printed on the products’ labels. These characteristics should make it much easier for FDA to design and require inserts and onserts that can survive the likely First Amendment attacks from the tobacco industry. But federal court case law continues to evolve relating to First Amendment protections of commercial speech, and considerable uncertainty exists as to how this evolving law might apply to new FDA efforts to require inserts or onserts.

Accordingly, this paper outlines the applicable statutory authorities and constraints relating to FDA requiring tobacco product inserts or onserts and suggests how they might be interpreted and applied most constructively by FDA and the courts. The paper then reviews applicable First Amendment law and carefully considers how the content and other characteristics of any required tobacco product inserts or onserts could be structured to minimize the risk of being blocked by First Amendment challenges. Although focusing on tobacco product inserts and onserts, this analysis also provides insights into how some key provisions of the Tobacco Control Act could be interpreted and applied to best promote the Act’s purposes, and on how FDA and other government regulators in other contexts might use product disclosures or other packaging, labeling, or advertising requirements to educate consumers or protect the public health without encountering First Amendment constraints.

Specific FDA Authority to Require Inserts and Onserts to Disclose Tobacco Product Constituents and Provide Other Information to Consumers

In its amendments to the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act (FCLAA), the Tobacco Control Act specifically mentions product inserts when it describes FDA’s authority to disclose information to consumers about tobacco product and tobacco smoke constituents.9 That text gives FDA authority to “prescribe disclosure requirements regarding the level of any cigarette or other tobacco product constituent including any smoke constituent . . . if the Secretary determines that disclosure would be of benefit to the public health, or otherwise would increase consumer awareness of the health consequences of the use of tobacco products.” It also states that, although such disclosures may not be required “on the face of any cigarette package or advertisement,” they may be provided “through a cigarette or other tobacco product package or advertisement insert, or by any other means.”10 And “by any other means” would presumably include onserts.11

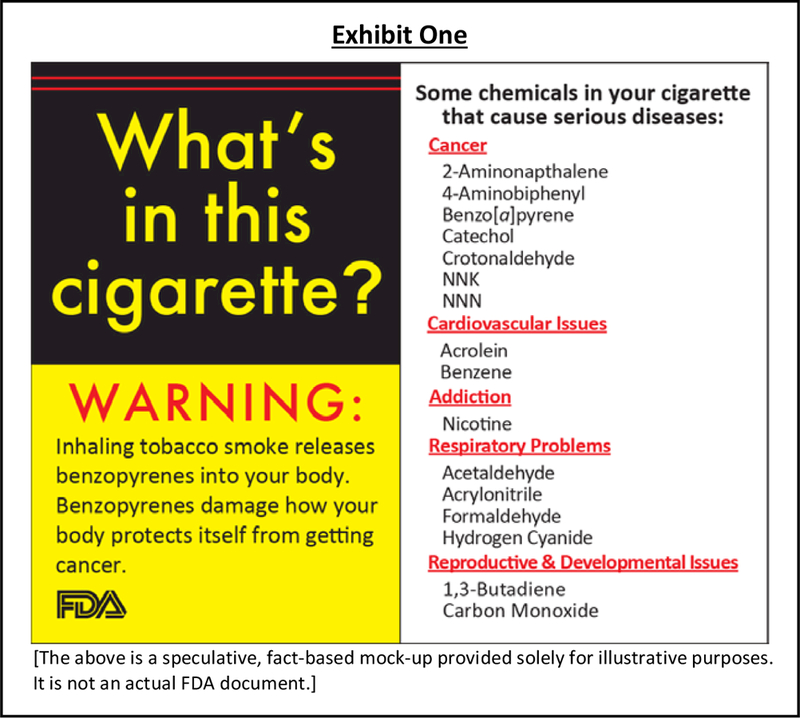

This language suggests that FDA could require inserts or onserts to disclose constituent levels (either generally or specifically) if it determined that doing so either “would be of benefit to the public health” or “would increase consumer awareness of the health consequences of the use of tobacco products,” even if it was not clear that the inserts or onserts would produce any actual reductions in tobacco use or its harms. Based on applicable evidentiary standards, however, FDA would at least need to make a reasonable determination, based on available evidence, that the disclosures of constituent levels in the inserts or onserts would be likely produce either a specific public health benefit (without any offsetting public health harms) or an increase in some specific type of consumer awareness of tobacco product health consequences.12 [For a possible example of such an insert or onsert, see Exhibit One.]

Figure 1.

Exhibit One

A provision adjacent to the Tobacco Control Act’s requirement that FDA “issue regulations that require color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking” on cigarette packs provides FDA direct authority to adjust any cigarette warnings it establishes “or establish the format, type size, and text of any other disclosures required under the . . . Act” if FDA finds that “would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with the use of tobacco products.”13 This text shows that the Act anticipated required disclosures other than those in the required warning labels, and further supports the legitimacy of disclosure requirements that promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with cigarette smoking, from other forms of tobacco use, or from tobacco use in general (even if it has not been determined that the disclosures will also reduce tobacco use or its harms).14

Using FDA’s General Tobacco Control Authorities to Require Inserts or Onserts to Provide Information to Consumers or for Other Public Health Purposes

FDA could also require inserts or onserts pursuant to the much broader and extensive authorities the Tobacco Control Act provides the agency to regulate the sale and promotion of cigarettes and other tobacco products15 or to establish tobacco product standards.16 To issue such regulations, FDA must determine that doing so would be “appropriate for the protection of the public health.”17 FDA must make that determination “with respect to the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and nonusers of the tobacco product, and taking into account— (A) the increased or decreased likelihood that existing users of tobacco products will stop using such products; and (B) the increased or decreased likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products.”18

The “appropriate for the public health” phrase and its statutory subparts have not been specifically interpreted by FDA or the courts. However, almost any possible reading or definition of the phrase suggests that it would be “appropriate for the protection of the public health” for FDA to require inserts or onserts to provide any accurate information relevant to the tobacco products and their use by consumers, so long as FDA reasonably determined, based on available research and other evidence, that doing so would likely produce a significant net benefit to the public health (with no risk of any unintended consequences that could completely offset those gains).19

It is also possible that FDA could use this authority to require such inserts or onserts even if FDA were not able to determine whether they would likely produce a net decline in overall tobacco use harms but still reasonably found that the requirement was “appropriate for the protection of the public health.” For example, it might be “appropriate for the protection of the public health” to require inserts or onserts to help prevent youth experimentation with or initiation into tobacco use. Or it might be enough to require inserts or onserts simply to provide consumers with information about the harmful and potentially harmful constituents in tobacco products or with other health-related information that would enable consumers of tobacco products to make more informed decisions about whether they consume the tobacco products or try to quit, how much they consume, or how they consume them – even if FDA could not determine whether doing that would also actually change consumer behavior or reduce overall tobacco use or tobacco use harms.20 [For a possible example, see Exhibit One.]

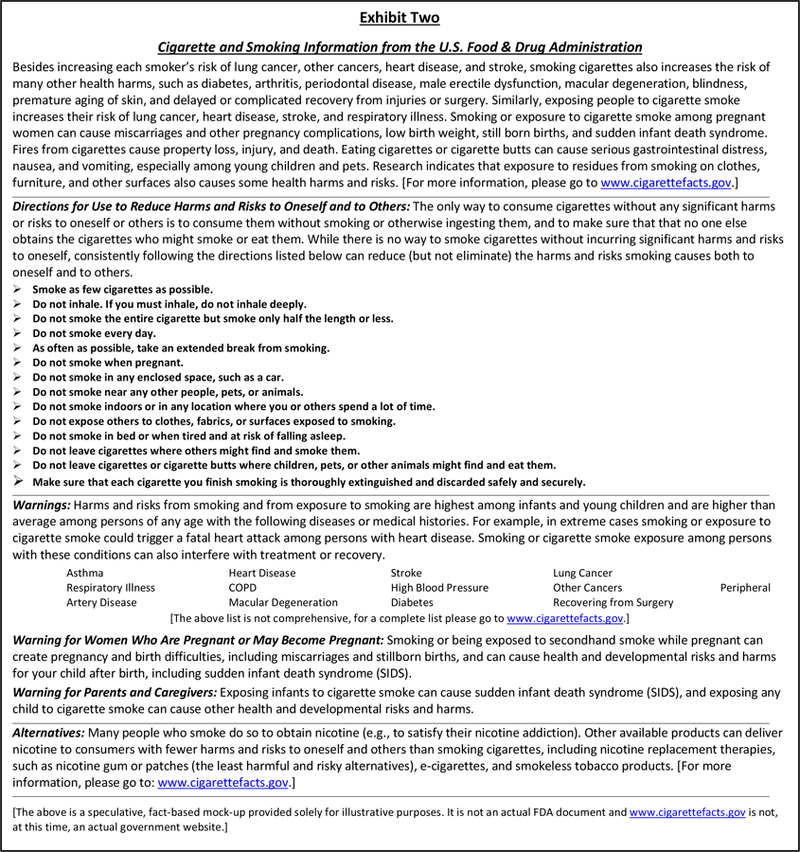

This same analysis applies to possible FDA tobacco product insert or onsert requirements for other purposes, beyond providing information about constituents, that would also be “appropriate for the protection of the public health.” For example, FDA might follow the example of its requirements for prescription and over-the-counter drugs and require tobacco product inserts and onserts to provide tobacco product consumers with “Instructions for Use” to inform them how to use the products to reduce risks and harms to the user and to others;21 or also to provide information on such matters as dosage forms and strengths, contraindications, warnings and precautions, adverse reactions, drug interactions, use while pregnant, overdosage, and dependence.22 [For a possible example, see Exhibit Two.]

Figure 2.

Exhibit Two

Similarly, FDA could use tobacco product inserts or onserts to notify consumers of the benefits from having regular medical tests to catch tobacco-caused disease early; or to provide information regarding the health benefits from cessation or switching to less harmful types of tobacco/nicotine products. Or FDA could use inserts or onserts to address existing misleading aspects of cigarettes or other tobacco products and their packaging and labels through color coding, certain descriptors, and other characteristics that make consumers inaccurately believe that some brands or subbrands are less harmful than others.23

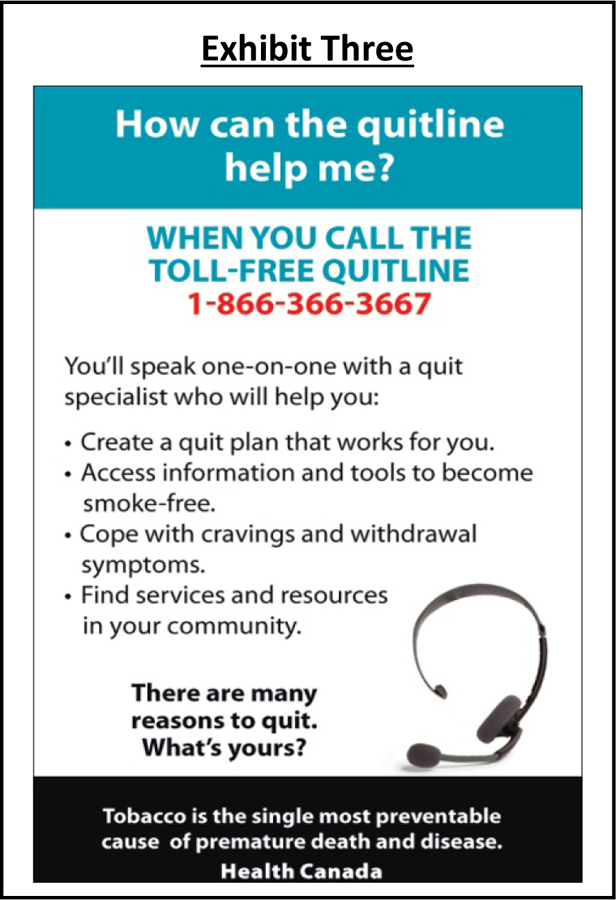

Another possibility would be for FDA to require inserts or onserts specifically to provide consumers with information about how to quit using the tobacco product or where to get cessation assistance, or even to provide messaging to encourage quit attempts and overall cessation.24 Recent studies from Canada, the only country that requires any cigarette inserts, suggest that they could be quite effective at increasing cessation. The Canadian inserts include eight rotating messages about the benefits of quitting and recommendations for increasing the likelihood of successfully quitting, which behavioral change theories stress as critical for promoting desired behaviors.25 [For an example, see Exhibit Three.] Research on the impact of the inserts suggests that they promote downstream self-efficacy to quit, increased quit attempts, and sustained abstinence from cigarettes.26

Figure 3.

Exhibit Three

For FDA to require inserts or onserts for any of these different purposes, the Tobacco Control Act requires only that FDA determine that such inserts or onserts would be “appropriate for the protection of the public health,” and that its determination not be “arbitrary or capricious.”27 Related case law firmly establishes that nothing close to scientific certainty is required in agency determinations of this kind, and that the courts must give FDA’s determinations considerable deference, so long as the agency considers all relevant information, pro and con, and follows all the required procedures. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court has explained that all an agency must do to avoid being found “arbitrary and capricious” is “examine the relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action” and, if that has been done, “a court is not to substitute its judgment for that of the agency.” 28

But even if FDA has clear authority to require such inserts or onserts as “appropriate for the protection of the public health” (or through any of its other authorities in the Tobacco Control Act), any such requirements must also fit within the constitutional constraints established by the First Amendment’s protections for “commercial speech.”

First Amendment Constraints on Government-Required Inserts or Onserts

Members of the tobacco industry would almost certainly file First Amendment challenges against any FDA or other government efforts to require tobacco product inserts or onserts, just as they did to strike down FDA’s graphic health warning rule.29 However, even if the existing court rulings on First Amendment protections for commercial speech are interpreted expansively, there appear to be ways to design any government-required tobacco product inserts or onserts to survive any such constitutional attacks.

The courts typically review government measures that require product disclosures or warnings (whether through labeling or product inserts or onserts) as “compelled commercial speech,” and apply much more permissive constitutional scrutiny than they do to government efforts to restrict what commercial entities may say on their own. As the U.S. Supreme Court has stated, ‘‘the First Amendment interests implicated by disclosure requirements are substantially weaker than those at stake when speech is actually suppressed.’’30 The standard First Amendment test for compelled commercial speech, initially established in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Zauderer ruling, requires that the compelled speech (e.g., a warning label or disclosure requirement) be “factual and uncontroversial” and “reasonably related” to the government’s interest (e.g., to prevent deception of consumers or reduce the possibility of consumer confusion), which includes not being so “unjustified or unduly burdensome” to “offend the First Amendment by chilling protected commercial speech.”31

In sharp contrast, government restrictions on what commercial entities themselves may say about their products and services must survive the more extensive 4-part First Amendment test first presented in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Central Hudson case, which requires that:

To qualify for First Amendment protection, the commercial speech must relate to lawful activity and not be false or misleading.

The government’s asserted interest in restricting the speech must be substantial.

The restriction must directly advance the government’s asserted interest.

The restriction must not be more extensive than necessary to serve the asserted government interest.32

In the appellate court case striking down FDA’s graphic health warnings rule, the D.C. Circuit court panel of three judges ruled two to one that the less stringent Zauderer test for government compelled commercial speech applied only when the compelled speech was directed at “preventing deception to consumers” – and that any compelled commercial speech (such as required inserts or onserts) directed at other government purposes (e.g., disclosing health and safety risks) were subject to the more restrictive Central Hudson test.33 But the full D.C. Circuit (ruling en banc) directly reversed that ruling in the American Meat Institute case, finding that the less-stringent Zauderer test could apply to government compelled commercial speech directed at other legitimate government purposes.34

Similarly, the Second Circuit has repeatedly found that Zauderer should apply in compelled commercial disclosure cases, even when consumer deception is not at issue, and the Central Hudson test should be applied to statutes that restrict commercial speech,.35 Following that approach, it has upheld compelled commercial speech directed at purposes other than preventing consumer deception, including required disclosures directed at protecting the environment36 and at combating obesity.37

Although the U.S. Supreme Court has not directly considered the issue, the previously discussed D.C. and Second Circuit rulings suggest that the less stringent Zauderer test should apply to cases involving compelled commercial speech directed at legitimate government purposes, even when those purposes are not to prevent or reduce consumer deception or misunderstanding.38 Moreover, the Supreme Court has stated that “the extension of First Amendment protection to commercial speech is justified principally by the value to consumers of the information such speech provides.”39 That suggests that compelled commercial speech directed at providing consumers with any valuable information relating to the products at issue should qualify for the more lenient Zauderer test, whether it addresses consumer deception or misunderstandings or not.40

Even if Zauderer were interpreted narrowly to apply only to compelled commercial speech relating to consumer deception, inserts or onsert directed at providing consumers with accurate, not misleading information about tobacco product harms and risks would still be likely to qualify for and pass the Zauderer test. For example, the Sixth Circuit refused to apply strict scrutiny instead of the Zauderer test to the Tobacco Control Act’s requirement that FDA issue a rule mandating graphic health warnings on all cigarette packs and ads, noting that disclosures of the serious risks that smoking involves were necessary “to avoid giving a false impression that smoking is innocuous” and to prevent advertising that “represents the alleged pleasures or satisfactions of cigarette smoking” from being deceptive.41 As detailed above, extensive research and court findings also firmly establish that certain ongoing characteristics of cigarettes and their packaging and labels continue to mislead smokers and others to believe, inaccurately, that some brands or sub-brands are less harmful than others.42 Inserts and onserts to correct those misunderstandings would fit under even the most narrow views of what compelled speech falls under the more lenient Zauderer test. As the U.S. Supreme Court stated in the 2010 Milavetz case, all that the government must do to justify compelled speech directed at preventing consumers from being misled is show that likelihood of consumer deception (without the compelled speech) “is hardly a speculative one.”43

It is also possible that an interpretation of Zauderer permitting compelled speech only to address consumer deception would not only allow compelled speech to stop the products and their packaging and labeling from deceiving and misleading consumers but would also allow remedial compelled speech directed at addressing the harms caused by such misleading product, packaging, and labeling characteristics.44 Such permitted remedial compelled speech could, for example, include inserts or onserts designed to provide deceived and misled consumers with information about how to quit successfully (if they chose to try to do so once provided with correct and not misleading information).

On the other hand, it is possible that government-required tobacco product inserts and onserts might actually be subject to an even more lenient standard than the Zauderer test because they would not be seen by consumers prior to purchase and are not displayed as part of the manufacturer’s commercial speech.45 This analysis applies most clearly to inserts because they are inside the tobacco product package, separate from the external package and its label, and completely invisible to consumers prior to purchase. But it could also apply to onserts that do not convey any messages to consumers until after they detach the onsert from the package and open it up. For example, in a different context the D.C. Circuit Court has ruled that onserts should not be considered to be statements on cigarette packaging because they are not a part of the packaging but only affixed to the packaging.46 More generally, the existence of the different Zauderer and Central Hudson tests are based on the concept that less stringent First Amendment protections should apply to less burdensome requirements and restrictions relating to commercial speech, which indicates that the First Amendment scrutiny applied to product inserts should be less strict than for onserts, which should, in turn, be less strict than the First Amendment scrutiny applied to warnings required on external product labeling or in all product advertisements.

A less exacting constitutional standard than the Zauderer test might also apply if the required tobacco product inserts or onserts clearly identify the government as the entity making and delivering the information they contain (and make it clear that the information is not coming from the product manufacturers).47 In such a situation, “[w]here the law requires a commercial entity engaged in commercial speech merely to permit a disclosure by the government, rather than compelling speech out of the mouth of the speaker, the First Amendment interests are less obvious.”48

Neither the U.S. Supreme Court nor any circuit court appears to have ruled on this exact issue. In Johanns v. Livestock Marketing Ass’n, however, the Supreme Court ruled that requiring manufacturers of a specific product to finance generic advertising by the government about the product does not raise any compelled speech or other First Amendment issues, even when the affected businesses objected to the government’s message.49 That ruling made a sharp distinction between compelling support for government speech, where the First Amendment does not apply, and either compelling individuals to personally express government messages as their own or compelling individuals or businesses to subsidize speech made by non-government third parties, where the First Amendment does apply.50 Following that same logic, a government-required insert or onsert that, on its face, clearly presents only government speech, with no implied endorsement by the tobacco product manufacturer, would appear to raise no First Amendment issues, especially where the manufacturer’s ability to deliver its own messages would not be restricted by the requirement.51

Even if the courts found that requiring a commercial product to deliver what was clearly the government’s own speech still raised First Amendment issues, the U.S. Supreme Court’s analysis in Johanns indicates that such compelled speech clearly identified as coming exclusively from the government should be subject to lesser First Amendment scrutiny compared to whatever the court might have applied if the speech were not identified as the government’s own. In addition, any such First Amendment concerns should be much weaker regarding insert or onsert requirements as opposed to required warning labels on product packages or labels, where (unlike with inserts or onserts) the required speech is seen prior to purchase and takes up product packaging space that the manufacturer could otherwise use for its own speech.

Regardless of which First Amendment test or standard might be applied, they all require that the content of any government-compelled speech be accurate and not misleading to avoid being struck down. To satisfy the Zauderer test (however interpreted), the compelled speech must also be “purely factual and uncontroversial.”52 In a recent D.C. Circuit case, the court stated that “‘uncontroversial, as a legal test, must mean something different than ‘purely factual.’”53 It found that the required speech at issue, although it could be seen as factual, failed the Zauderer test because it was ideological and metaphorical and suggested that the products were ethically tainted, which was a value judgment that could be contested.54

In the D.C. Circuit’s earlier RJ Reynolds case striking down FDA’s final cigarette warning label rule, the court found that compelled speech cannot qualify as “purely factual and noncontroversial” if it includes graphic images that, while not “patently false” can be misunderstood; are “primarily intended to evoke an emotional response or, at most, shock the viewer into retaining the information in the textural warning; are “not warnings but admonitions,” and are “unabashed attempts to . . . browbeat consumers into quitting.”55 Similarly, both the majority opinion and the dissent found that including the phone number “1–800-QUIT-NOW” in the warning labels, as an exhortation to quit, was not “purely informational,” either.56

Raising a possible additional constraint, a footnote in the majority opinion in R.J. Reynolds stated that: “Like the district court, we are skeptical that the government can assert a substantial interest in discouraging consumers from purchasing a lawful product, even one that has been conclusively linked to adverse health consequences.”57 Although this statement is only dictum (not binding precedent), it raises the possibility that future court rulings might determine that regard less of what First amendment test is applied and regardless of what substantial interest the government asserts the government may not compel commercial speech by tobacco product manufacturers that includes any direct encouragement for adults not to purchase or use the manufacturers’ tobacco products so long as those tobacco products are lawful products. While the dissent in R.J. Reynolds noted that the “QUIT NOW” command in the FDA-required cigarette warning labels “directly contradicts the tobacco companies’ desired message at the point of sale, thereby imposing a significant burden on their protected commercial speech,” it did not suggest that such compelled speech discouraging the use of the companies’ products was incompatible with the First Amendment. Instead, the dissent stated only that the “QUIT NOW” command could not be sustained under the Central Hudson test unless the government could explain why a less burdensome “alternative means of connecting smokers to cessation resources, such as a package insert,” would be inadequate.58

The R.J. Reynolds ruling was not appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and it is not yet clear how the Supreme Court might handle a similar case. In the meantime, the Supreme Court’s rulings in the Zauderer case remain controlling law, clearly establishing that any government compelled commercial speech (including inserts or onserts) must not only present “purely factual and uncontroversial information” but must also be “reasonably related” to a substantial government interest.”59

Zauderer notes that “unjustified or unduly burdensome [compelled speech] might offend the First Amendment by chilling protected commercial speech.”60 But Zauderer also states that such concerns do not apply “as long as [the compelled speech] requirements are reasonably related to the State’s interest in preventing deception of consumers;”61 and the U.S. Supreme Court followed that ruling in the Milavetz case, its most recent compelled speech case.62

In any case, the courts have not found warning labels that use large portions of the main display portions of product packaging to be overly burdensome;63 and required inserts or onserts would be even less burdensome in that regard. It is possible, however, that a court might still find a government insert or onsert requirement overly burdensome if it were extremely costly for manufacturers to comply. But such cost concerns would not arise so long as the inserts or onserts did not require major changes to the packaging currently used for the tobacco products and roughly paralleled the insert and onsert requirements, and related costs, currently imposed on manufacturers in other areas, such as prescription and over-the-counter drugs. It would also be hard for the tobacco industry to argue that insert and onsert requirements are overly burdensome when they have been using both for their own purposes for decades.64

How Might FDA Design a New Insert-Onsert Rule to Comply with Existing First Amendment Case Law

As discussed above, the existing case law suggests that a new FDA rule requiring tobacco product inserts or onserts would almost certainly avoid First Amendment constraints if the inserts or onserts:

-

(a)

Were purely factual, informative, and noncontroversial (which would also make them accurate and not misleading).65

-

(b)

Provided consumers with valuable information about the tobacco products, such as information about the tobacco products’ harms and risks, how to use the products to minimize harms and risks, and how to dispose of the products safely.

-

(c)

Were required in order to address consumer ignorance that could mislead consumers or otherwise prevent or reduce consumer deception or misunderstandings about the products and their use and related consequences.

-

(d)

Were unambiguously identified as coming from the government or some unit of the government (and not from the products’ manufacturers).66

-

(e)

Were not extremely costly or difficult for manufacturers to implement.

More rigorous First Amendment obstacles could arise, however, if the required inserts or onserts included text or graphic images that were subject to different interpretations or provoked emotional responses, or if they explicitly encouraged specific consumer behaviors contrary to the manufacturer’s interests, such as not buying the product in the first place, quitting all future use, or switching to less harmful tobacco or nicotine products. To avoid this risk, such elements could simply be omitted.67

At the same time, it should be perfectly acceptable under existing First Amendment law regarding compelled commercial speech if the FDA-required inserts or onserts provide consumers with accurate, not misleading, factual information about the health benefits from terminating or sharply reducing use of the subject tobacco product or from switching completely to using a less harmful tobacco or nicotine-delivery product and perhaps even about how to quit successfully for those that choose on their own to do so so long as there were no controversial or misleading graphic images, emotional appeals, or actual exhortations to quit or switch.

Although there are no court rulings directly on point, an FDA rule requiring such inserts or onserts should readily fall under the relaxed Zauderer test, even if Zauderer were applied only to compelled speech directed at reducing consumer deception and misunderstandings. As noted previously, courts have already found that informing consumers about tobacco use risks and harms qualifies as addressing consumer deception and related misleading commercial speech; 68 and also providing information on how to quit successfully would help to correct the harms caused by past deceptive or misleading speech that have misled consumers to start or not try to quit. Moreover, it would not be difficult to show that providing the above-described information to consumers through inserts or onserts is “reasonably related” to the goal of reducing consumer misunderstandings and preventing consumer deception relating to such matters as the health benefits (or lack thereof) from: (a) switching between brands or sub-brands; (b) reducing one’s consumption to different degrees; (c) switching completely to using a less-harmful product compared to engaging in dual use; or (d) quitting completely versus other harm reduction strategies.69

If Zauderer were applied more broadly (beyond just preventing deception), it would be quite easy to establish that such purely informational disclosures or messages were also “reasonably related” to various alternative government’s interests, such as: (a) having adult consumers make more fully informed decisions about tobacco product use; (b) providing helpful information to the many smokers and other tobacco users who want to quit but have not been able to do so successfully because of their addiction; (c) preventing youth initiation and use; or even (d) reducing overall tobacco use and harms.

But if FDA wanted to required tobacco product inserts or onserts specifically to prevent and reduce youth tobacco use or reduce overall tobacco use harms as effectively as possible, the agency would likely want to use such potentially helpful tools for breaking through the addictive power of cigarettes and other tobacco products as emotional appeals; not-purely-informational graphic images; or direct exhortations to quit, reduce use, or switch to less-harmful products. Including such elements in the inserts and onserts, however, would likely trigger the application of the more restrictive Central Hudson test. Accordingly, FDA would not want to include any of those elements unless it had formally determined that doing so would likely make the inserts or onserts significantly more effective at preventing youth use or reducing overall tobacco use harms – and based that determination on a careful consideration of the available relevant research and evidence, both pro and con.

In this regard, new research showing what specific elements or characteristics in tobacco product inserts or onserts would make them most effective at promoting different possible government goals would be especially helpful. In particular, research showing that including emotional appeals, different types of graphic images, and direct exhortations to quit, cut back, or switch in inserts or onserts would make them more effective at preventing youth initiation, promoting cessation, or otherwise reducing tobacco use harms would make it easier to pass the part of the Central Hudson test requiring a reasonable government determination that the inserts and onserts would directly promote the government’s substantial interests.70

To satisfy the remainder of the Central Hudson test, FDA would also have to establish that there were no equally or more effective ways to promote the government interests that would interfere less with the manufacturer’s protected commercial speech.71 That should not be too difficult because required inserts or onserts would burden manufacturers’ commercial speech rights far less then advertising or labeling restrictions or compelled speech in product advertising or on product packaging or labels.72 Most notably, consumers would not even see the inserts until after making a decision to purchase the product, the inserts would not obscure any manufacturer commercial speech made through externally visible packaging and labeling, and the inserts would not be visible to the general public. It is hard to imagine any other form of government-compelled speech to deliver information or other messages to product consumers that could possibly be less burdensome to the manufacturers’ speech than product inserts.73

Onserts that did not present any messages to consumers until detached from the package and opened would share these same less- burdensome characteristics with inserts, except for temporarily obscuring the part of the tobacco product package where the onsert was affixed (which could be its warning label). But an onsert could be harder to defend against First Amendment attacks if it were required to be affixed to the front of the tobacco product package, obscuring more of the manufacturer’s commercial speech, or if it included text visible before purchase that directly contradicted the manufacturers’ “Buy-Me” protected speech at point of sale (e.g., by the visible onsert stating “QUIT NOW”). Even then, however, research showing that such characteristics made the onsert work more effectively to promote the government’s substantial interests would make placing those burdens on the manufacturer’s speech more constitutionally permissible.

Clearly, FDA has the statutory authority to require tobacco product inserts or onserts and could structure a new insert-onsert rule to fit within existing First Amendment constraints. Although currently available research and other evidence provides a sufficient basis for such FDA action, additional research would not only provide additional support but could also enable FDA to require inserts or onserts with specific characteristics and elements that would work even more effectively to reduce tobacco use and its harms.

Other Legal Issues with Insert or Onsert Requirements and How FDA Could Address Them

If FDA were to require inserts or onserts on cigarette packs or any other tobacco product packaging to provide consumers with information about product risks or harms or how to reduce them, tobacco product companies might argue (as they have in regard to government required warning labels)74 that complying with the insert-onsert requirement had reduced or eliminated any legal duty the tobacco companies otherwise had to warn or educate consumers, or even not to mislead consumers, through product packaging and labeling or other means. This argument could be refuted, however, if the law authorizing or establishing an insert or onsert requirement explicitly stated that nothing in the insert or onsert requirement shall be construed to affect the legal duties of any tobacco product manufacturer, distributor, or seller, or any related legal actions. The Tobacco Control Act already has some provisions of this type built into it that cover subsequent FDA tobacco control rulemaking, but they could be fortified or supplemented.75 In addition, FDA could explicitly state in any new insert-onsert rule that it did not intend the rule to provide any new legal protections for any tobacco industry members or to preempt any other laws establishing duties on tobacco product manufacturers to warn or inform consumers.

To provide additional protection against possible tobacco industry legal challenges, any new FDA insert-onsert rule could also provide a formal process that affected manufacturers could initiate to propose any changes to the required inserts or onserts necessary to make them more accurate, complete, and not misleading.76 The Tobacco Control Act already provides for ways that interested parties can attempt to initiate FDA action relating to tobacco products, including amendments to FDA rules.77 But the process proposed here would provide tobacco manufacturers and other interested parties a more direct and dispositive tool for seeking and securing timely corrections and improvements to the required inserts or onserts (e.g., by including related agency deadlines). To place more responsibility on the tobacco product manufacturers, the process could also require that they provide FDA with any relevant new research or other information relating to the accuracy, completeness, or effectiveness of the information provided in the inserts or onserts that the manufacturers develop or otherwise obtain that is not publicly available.

Establishing an administrative process that tobacco product manufacturers or others could use to correct or update any required inserts and onserts could also strengthen the insert-onsert rule’s defenses against First Amendment attacks. On the front end, the courts would likely look even more favorably on an industry-challenged insert-onsert rule if it not only appeared to require inserts or onserts that, based on available research and other evidence, were wholly accurate, purely informational, and not misleading but also offered an explicit and effective process that manufacturers and others could initiate to revise the compelled speech if any new research or information established that the inserts or onserts were not accurate, purely informational, and not misleading.78 On the back end, offering such a process would provide manufacturers a way to prompt FDA to fix the required inserts or onserts in a timely fashion whenever new evidence showed that was necessary for constitutional compliance – instead of having to take the more extreme action of immediately bringing a new lawsuit to try to strike down the entire requirement.79

When used, this provided process would either produce a government agency determination, based on its expert review of the new research and evidence, that no First Amendment violations were occurring and no modifications to the required compelled speech were necessary, or prompt agency action to revise the compelled speech to eliminate any constitutional violations while still continuing to promote the government’s related interests or purposes. Because these administrative outcomes would either resolve the issue completely (making any subsequent court review unnecessary) or provide a more complete evidentiary record and more refined controversy for any subsequent court review, the courts would likely require the tobacco companies to use this process to exhaust their administrative remedies before bringing any such constitutional challenges to the courts.80

Existing provisions in the Tobacco Control Act already allow interested third parties to petition FDA to amend an established rule;81 and the courts might consider them to be sufficiently explicit and dispositive to constitute available administrative remedies that manufacturers must exhaust before using new research or other new evidence to attack an already established insert or onsert requirement in court.82 But the more explicit and dispositive proposed new procedures discussed here, with specific agency deadlines, would more easily and certainly qualify as a readily available administrative remedy that is neither “futile” nor “inadequate to prevent irreparable injury” which manufacturers must, consequently, exhaust before taking their related claims to court83 especially if the final insert-onsert rule also required manufacturers to submit any new research or other information they subsequently developed or obtained that indicated that the messaging in the required inserts or onserts was inaccurate, not purely informational, or misleading so that the agency could make any necessary changes to the messaging.84

Conclusion

Tobacco product inserts or onserts provide an effective way for governments to deliver constructive information and guidance to consumers and to promote related public health goals, yet they are rarely used or even considered. This paper has shown that FDA has clear statutory authority to implement tobacco product insert or onsert requirements to educate and inform consumers about tobacco product use, harms and risks; to promote tobacco use cessation and prevent initiation and relapse; or to protect or promote the public health in other ways. In addition, any new FDA insert-onsert rule would face more permissive First Amendment hurdles than those confronting rules requiring warning labels on tobacco product labels, packaging or ads. Indeed, FDA could readily design a new insert-onsert rule to be entirely consistent with any First Amendment constraints on compelling or restricting the commercial speech of tobacco product manufacturers that the courts might reasonably apply.85

Additional research regarding the effectiveness of different types of inserts or onserts to promote different possible government interests would provide increased insight into their value and effectiveness compared to other tobacco control options available to FDA and to other governments. Such new, additional research could also fortify the existing research and other evidence that would support any new insert-onsert requirements against the First Amendment challenges and other legal attacks that members of the tobacco industry would likely bring to try to avoid or delay having to comply.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Thrasher’s involvement in the writing of this paper was partly supported by a grant from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (R01 CA167067). The funder had no role in the design, analysis, preparation, or decision to publish the manuscript. The opinions and analysis in the article are the authors’ own.

Footnotes

Tobacco Control Act (TCA), Public Law 111–31, Sec. 201(a), codified at 15 USC § 1333(d). [Pursuant to an apparent typo in the Tobacco Control Act, there are now two subsection (d)’s in 15 USC § 1333. This reference refers to the first (d).]

FDA, Final Rule, Required Warnings for Cigarette Packages and Advertisements, 21 CRF Part 1141, Federal Register 76(12): 36628–36777 (June 22, 2011).

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012)[affirming the initial ruling in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., v. FDA, 845 F.Supp2d 266 (USDC, DC 2012). But see American Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, 760 F.3d 18 (D.C. Cir. 2014) [overruling one of the core holdings in Reynolds v. FDA]. These rulings are discussed more fully, below.

FDA, Final Rule, Deeming Tobacco Products to be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products, 21 CFR Parts 1100, 1140, and 1143 at 1143.3, Federal Register 81(90): 28974–29106 (May 10, 2016) at 29103–106

See, e.g., Gerard S. Petrone, Tobacco Advertising: The great seduction (1996) at 54–60, 147–48, 154–55; Arlene B. Hirschfelder, Encyclopedia on Smoking and Tobacco (1999) at 2–3; Joseph G. L. Lee, et al., Promotions on Newport and Marlboro Cigarette Packages: A National Study, NICOTINE & TOBACCO RES. (Epub September 9, 2016).

James F. Thrasher, et al., Cigarette Package Inserts can Promote Efficacy Beliefs and Sustained Smoking Cessation Attempts: A Longitudinal Assessment of an Innovative Policy in Canada, 88 PREVENTIVE MED. 59–65 (2016); James F. Thrasher, et al., The Use of Cigarette Package Inserts to Supplement Pictorial Health Warnings: An Evaluation of the Canadian Policy, 17 NICOTINE & TOBACCO RES. 870–875 (2015).

Research on the efficacy of product inserts and onserts in non-tobacco contexts is sparse. See, e.g., D. Grober-Gratz, et al., Der Einfluss des Beipackzettels auf die medikamentöse Adhärenz bei hausärztlichen Patienten [Influence of Package Inserts on Adherence to Medication in Primary Care Patients], 137 DEUTSCH MED WOCHENSCHR 1395–1400 (2012); Rowa Al-Ramahi, et al., Attitudes of Consumers and Healthcare Professionals Towards the Patient Package Inserts - a Study in Palestine, 10 PHARMACY PRACTICE (INTERNET) 57–63 (2012). It is possible that government-required health-information-directed inserts and onserts for cigarettes and other tobacco products would be more frequently and carefully considered by consumers due to their novelty and the typical absence of any product information or directions from other sources and because the vast majority of smokers have concerns about tobacco use and want to reduce the related harms or quit. The effectiveness of tobacco product inserts or onserts could also be increased by ensuring they could be quickly and easily understood by those with lower literacy levels. See, e.g., Stephanie M. Weiss & Stephanie Y. Smith-Simone, Consumer and Health Literacy: The Need to Better Design Tobacco-Cessation Product Packaging, Labels, and Inserts, 38 AMERICAN J. OF PREVENTIVE MED. S403-S413 (2010).

TCA Sec. 206, amending Sec. 4 of FCLAA, 15 USC 1333. A tobacco product “constituent” includes tobacco product additives and ingredients, as well as any new substances created during the product’s use (e.g., through the combustion of the original ingredients). That is expressly stated in Sec. 915(b)(1) and (2) [21 USC 387o(b)(1) and (2)] and clearly implied in the FCLAA provision, as amended by the TCA, which refers to “any cigarette or other tobacco product constituent, including any smoke constituent.” USC 1333(e)(3).

15 U.S.C. 1333(e)(3).

It is possible that the 15 U.S.C. 1333(e)(3) ban on requiring constituent disclosures “on the face” of any cigarette packs might be interpreted to block FDA from using this section to require that an onsert disclosing constituent levels be affixed to the face of a cigarette package, despites its being readily removable from the pack face by the consumer. But, even under such an interpretation, placing such an onsert on the back or side of cigarette packs would still be permitted. In addition, this pack-face restriction does not, by its terms, apply at all to any tobacco products other than cigarettes or to any FDA onsert requirements not based on this specific section of the Tobacco Control Act (although the tobacco companies would certainly argue that it should be interpreted to apply to any FDA onsert requirement placed on any tobacco product).

See supra, notes 15–18 and 26–27, and corresponding text.

TCA Sec. 202(b), amending FCLAA at 15 USC § 1333(d). [Pursuant to the TCA amendments, there are two subsection (d)’s in 15 USC § 1333. This reference refers to the second (d).] For parallel provisions relating to warning labels and disclosures on smokeless tobacco product labels, see TCA Sec. 205(a), amending the Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Health Education Act at 15 USC § 4402(d).

Inserts or onserts could also be used pursuant to TCA Sec. 915(b)(2), which states that FDA “may require that tobacco product manufacturers, packagers, or importers make disclosures relating to the results of the testing of tar and nicotine through labels or advertising or other appropriate means, and make disclosures regarding the results of the testing of other constituents, including smoke constituents, ingredients, or additives, that the Secretary determines should be disclosed to the public to protect the public health and will not mislead consumers about the risk of tobacco related disease.” TCA Sec. 915(b)(2); 21 USC § 387o(b)(2). They might also be used toward satisfying the requirement in TCA Sec. 904(d)(1)&(e) that FDA publish and periodically revise as appropriate “in a format that is understandable and not misleading to a lay person, and place on public display (in a manner determined by [FDA]). . . a list of harmful and potentially harmful constituents, including smoke constituents, to health in each tobacco product by brand and by quantity in each brand and subbrand.” TCA Sec. 904(d)(1)&(e); 21 USC § 387d(d)(1)&(e).

TCA Sec. 906(d)(1); 21 USC § 387f(d)(1).

TCA Sec. 907(a)(3); 21 USC § 387g(a)(3).

FDA could also require inserts or onserts for specific tobacco products that must obtain a new product orders to permit their legal sale in the United States if FDA determined that requiring the inserts or onserts as part of the orders was “appropriate for the protection of the public health” (or was necessary for the tobacco products to meet other requirements for qualifying for the orders). TCA Sec. 910(c) and (d), 21 USC § 387j(c) and (d). Similarly, FDA could require inserts or onserts for specific tobacco products that must obtain a modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) order to permit their legal sale in the United States if FDA determined that requiring the inserts or onserts as part of the orders was necessary to ensure that allowing the product on the market would significantly reduce harm and the risk of tobacco-related disease to individual users and would “benefit the health of the population as a whole taking into account both users of tobacco products and persons who do not currently use tobacco products.” TCA Sec. 911(g)(1), 21 USC § 387k(g)(1). See, also, TCA Sec. 911(g)(2), 21 USC § 387k(g)(2), especially at (A)(i).

TCA Sec. 906(d)(1); 21 USC § 387f(d)(1).

A plain reading of the terms also suggests that finding an insert or onsert requirement to provide constituent information “appropriate for the protection of the public health” would be easier than finding that it would “be of benefit to the public health” -- as in the FCLAA standard at 15 U.S.C. § 1333(e)(3) -- or that its information “should be disclosed to the public to protect the public health” – as required in § 915(b)(2) [21 USC § 387o(b)(2)].

Some might misconstrue the D.C. Circuit ruling in the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA graphic health warnings case as rejecting the idea that simply providing consumers with information could be “appropriate for the protection of the public health” because it struck down the FDA’s health warning rule as not being likely to produce smoking reductions. 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012). In that case, however, the court stated that because “[t]he only explicitly asserted interest [by FDA] is an interest in reducing smoking rates,” it would use only that interest in its First Amendment analysis (and not consider other possible government interests, such as informing consumers). Accordingly, the question of whether it would be “appropriate for the protection of the public health” solely to increase consumer knowledge about tobacco product harms or how to reduce them was not at issue and was not decided by the court. Id. at 1218–19.

See e.g., General Labeling Provisions: Drugs; Adequate Directions for Use 21 CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS (CFR) 201.5.

For examples of FDA-required labeling and inserts for prescription and over-the-counter drugs, see the Drugs@FDA database at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda, accessed August 12, 2016. See, also, e.g., Requirements on Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products, 21 CFR 201.56; and Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA, Guidance for Industry: Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products – Implementing the PLR Content and Format Requirements (February 2013). Because of FDA’s much broader tobacco control authorities, the agency would have considerably more flexibility regarding what it might require in any tobacco product inserts or onserts than it does for drugs or other products it regulates.

See, e.g., Hua-Hin Yong, et al., U.S. Smokers’ Beliefs, Experiences and Perceptions of Different Cigarette Variants Before and After the FSPTCA Ban on Misleading Descriptors such as ‘Light’, ‘Mild’, or ‘Low,’ NICOTINE & TOBACCO RES. (Epub April 15, 2016); Laura K. Lempert & Stanton A. Glantz, Packaging Colour Research by Tobacco Companies: the Pack as Product Characteristic, TOBACCO CONTROL (Epub June 2, 2016); Ron Borland & Steven Savvas, Effects of Stick Design Features on Perceptions of Characteristics of Cigarettes, 22 TOBACCO CONTROL 331–37 (2013); Maansi Bansal-Travers, et al., What do Cigarette Pack Colors Communicate to Smokers in the U.S.?, 40 AM. J. OF PREVENTIVE MED. 683–689 (2011); Maansi Bansal-Travers, et al., The impact of Cigarette Pack Design, Descriptors, and Warning Labels on Risk Perception in the U.S., 40 AM. J. OF PREVENTIVE MED. 674– 682 (2011); David Hammond & Carla Parkinson, The Impact of Cigarette Package Design on Perceptions of Risk. J. of Public Health (Epub July 27, 2009); USA v. Philip Morris, 449 F. Supp. 1, 1609 (DC Dist. Ct. 2006) and at findings of fact 2024, 2379. 2412–14, 2448–49, 2469, 262–28 [findings upheld in: USA v. Philip Morris, 566 F.3d 1095 (DC Cir. 2009]; Melanie Wakefield, et al., The Cigarette Pack as Image: New Evidence from Tobacco Industry Documents, TOBACCO CONTROL 11(Supp.1): i73-i80, 2002.

As discussed below, any such inserts or onserts would also need to comply with applicable First Amendment standards, which may apply more strictly to compelled speech that discourages the legal use of the associated product.

Albert Bandura, Social Learning Theory (1977); Albert Bandura, Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change,” 84 PSYCHOL. REV. 191–215 (1977); James O. Prochaska & Carlo C. DiClemente, “Self Change Processes, Self-efficacy and Decisional Balance Across Five Stages of Smoking Cessation,” in Alan R. Liss (ed.), Advances in Cancer Control: Epidemiology and Research (1984).

James Thrasher, et al., The Use of Cigarette Package inserts to Supplement Pictorial Health Warnings: An Evaluation of the Canadian Policy, 17 NICOTINE & TOBACCO RES. 870–75 (2015); James Thrasher, et al., Cigarette package Inserts Can Promote Efficacy Beliefs and Sustained Smoking Cessation Attempts: A Longitudinal Assessment of an Innovative Policy in Canada, 88 PREVENTIVE MED. 59–65 (2016).

TCA Sec. 912(b); 21 USC § 387l(b) [referencing the Administrative Procedures Act at 5 USC § 706].

FCC v. Fox Television Stations, 129 S.Ct. 1800, 1810 (2009) (quoting Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Assn. of United States, Inc. v. State Farm Mut. Automobile Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983)). See, also, Kroger Co. v. Reg’l Airport Auth., 286 F.3d 382, 389 (6th Cir. 2002) [“If there is any evidence to support the agency’s decision, the agency’s determination is not arbitrary or capricious”].

See, e.g., R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985) at note 14.

Zauderer, 471 U.S. at 651. See, also, Milavetz, Gallop & Milavetz, P.A. v. U.S., 559 U.S. 229 (2010); Am. Meat Inst. 760 F.3d 18, 21–22 (D.C. Cir., 2014) (en banc).

Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Pub. Serv. Commission of N.Y., 447 U.S. 557, 566 (1980). See, also Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly, 533 U.S. 525 (2001)[the most recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of government restrictions on tobacco product advertising].

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

Am. Meat Inst., 760 F.3d 18, 21–22 (D.C. Cir., 2014) (en banc). The ruling upheld government requirements that certain meat products disclosure their country of origin on their labels, referencing the long history of country-of-origin labeling directed at enabling consumers to choose American-made products, especially in regard to health concerns. Id. at 23–24. In an “en banc” session of a circuit court, the case is heard by all the judges of the circuit (typically on an appeal of a prior ruling by the typical three-judge circuit court panel), with all the judges in the circuit participating in the final ruling. The American Meat Inst. en banc case was considered by eleven circuit court judges, with two judges dissenting from the final ruling.

Safelite Group, Inc. v. Jepsen, 764 F.3d 258, 262–63 (2d Cir. 2014).

National Electric Manufacturers Ass’n v. Sorrell, 272 F.3d 104, 115 (2d Cir. 2001) [also noting that “To be sure, the compelled disclosure at issue here was not intended to prevent ‘consumer confusion or deception’ per se . . . but rather to better inform consumers about the products they purchase”].

New York State Restaurant Ass’n v. New York City Board of Health, 556 F.3d 114, 118 (2d Cir. 2009).

In regard to a more expansive application of the Zauderer test, see, also, International Dairy Foods Ass’n v. Boggs, 622 F.3d 628, 641 (6th Cir. 2010) [Zauderer test applies to disclosures to address not only inherently misleading commercial speech but also potentially misleading commercial speech]; and Pharmaceutical Care Management Ass’n v. Rowe, 429 F.3d 294, 310 at note 8 (1st Cir. 2005) [stating that a submitted brief offered no cases supporting its assertion that Zauderer is limited to potentially deceptive advertising directed at consumers and that “we have found no cases limiting Zauderer in such a way”]. In regard to a more restrictive application of the Zauderer test, see Borgner v. Brooks, 284 F.3d 1204, 1210– 13 (11th Cir.2002) [applying Central Hudson test, instead of Zauderer, to required disclosures without explanation].

Zauderer 471 U.S. at 651.

Coming at it the other way, the Second Circuit has stated that “consumer curiosity alone is not a strong enough state interest to sustain the compulsion of even an accurate factual statement.” International Dairy Foods Ass’n v. Amestoy, 92 F.3d 67, 74 (2nd Cir. 1996) [quoted favorably by both a concurring opinion (Kavanaugh) and a dissent (Brown) in American Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dept of Agriculture, 760 F.3d 18, 32 (DC Cir. 2014). What might constitute “consumer curiosity, alone,” however, is quite controversial. In Int’l Dairy Foods, the court struck down a Vermont law requiring the disclosure of what milk products contained milk from cows treated with synthetic growth hormone because it was compelled speech directed solely at addressing consumer curiosity (with that finding largely based on an FDA determination that the milk from such cows was no different from milk from non-treated cows and no related health harms or risks to consumers). 92 F.3d at 74, 73. For a critique of the court’s finding that consumer concerns about milk from cows treated with synthetic growth hormone amounts to only consumer curiosity and cannot justify the compelled speech at issue in the case, see, e.g., the dissent at 92 F. 3d at 74–81; and Sugarman, SD, Should Food Businesses Be Able to Use the First Amendment to Resist Providing Consumers with Government-Mandated Public Health Messages, FDLI’S FOOD AND DRUG POLICY FORUM 5(4) (April 29, 2015). See, also, American Meat Inst. 760 F.3d at 23 [compelling product country-of-origin information includes health and safety interests and “has an historical pedigree that lifts it well above ‘idle curiosity’”].

Discount Tobacco City & Lottery Inc. v. U.S., 674 F.3d 509, 526 (6th Cir. 2012), quoting Cipollone v. Liggett Group, Inc., 505 U.S. 504, 527 (1992).

Supra, note 23. See, also, infra, note 69.

Milavetz, Gallop & Milavetz, P.A. v. U.S., 559 U.S. 229, 251 (2010)[quoting Zauderer, 471 U.S. at 652].

See, e.g., Am. Meat Inst., 760 F.3d 18, note 3 (D.C. Cir., 2014) (en banc)[ compelled disclosures that provide purely factual and uncontroversial information “to correct deception” are subject to the basic Zauderer test and not subject to strict scrutiny]; and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205, 1215–16 (D.C. Cir. 2012) [discussing remedial disclosures to dissipate the effects of past deceptive representations].

See, e.g., the dissent in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205, 1236 (D.C. Cir. 2012) [suggesting that requiring cigarette package inserts is less burdensome, under First Amendment analysis, than requiring warning labels on the packs]; and National Ass’n of Manufacturers v. S.E.C., 800 F.3d 518, 522–24 (DC Cir. 2015)[finding that a government compelled speech requirement unconnected to voluntary advertising or to product labeling at the point of sale is not compelled commercial speech subject to the Zauderer test]. Although the National Ass’n of Manufacturers case applied the more stringent Central Hudson test to the compelled speech at issue, that was based on a finding that requiring certain public disclosures on company websites and in their regular reports to the SEC faced even stronger First Amendment constraints than requiring disclosures in product ads or labeling, and inserts or onserts are not as publicly visible or as directly and formally linked to the product’s manufacturer as disclosures on company’s own website or in its own SEC filings. See, also, the dissent in National Ass’n of Manufacturers, noting the “strange” and “highly curious results” from providing stronger First Amendment protections for compelled statements on websites and SEC filings than for compelled statements on product labels or advertising, which “would impose a more searching First Amendment standard on a disclosure that imposes a less burdensome requirement on the speaker.” 800 F.3d at 535.

U.S. v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 566 F.3d 1095, 1140–42 (DC Cir. 2009)[noting, also, that the tobacco companies consider onserts to be different from packaging or labeling on the packaging].

See, e.g., CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, California, __F.Supp.3d__ (USDC, ND CA, 2015)[“there is a persuasive argument that, where, as here, the compelled disclosure is that of clearly identified government speech, and not that of the private speaker, a standard even less exacting than that established in Zauderer should apply”].

CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, California, __F.Supp.3d__ (USDC, ND CA, 2015). In Pacific Gas and Electric Co. v. Public Utilities Commission, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a law requiring a utility to include a third party’s newsletter, clearly identified as such, in the utility’s monthly billing statements to consumers. 475 U.S. 1 (1986). But the compelled speech in Pacific Gas was political not commercial speech, controversial opinion (including views hostile to or biased against the utility), neither factual nor noncontroversial information, and was from a third party not the government. Accordingly, it does not contradict the idea that compelled factual and noncontroversial commercial speech that would otherwise fit under the Zauderer test could actually be subject to an even less restrictive test if it were clearly identified as coming from the government and not the manufacturer.

Johanns v. Livestock Marketing Ass’n, 544 U.S. 550 (2005). See, also, Walker v. Texas Div., Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 2239, 2245 (2015) [“When government speaks, it is not barred by the Free Speech Clause from determining the content of what it says. That freedom in part reflects the fact that it is the democratic electoral process that first and foremost provides a check on government speech.” (internal citation omitted)]. At the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Wooley v. Maynard – that the First Amendment prohibits state governments from requiring license plates with ideological government messages (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die” motto) – remains good law. 430 U.S. 705 (1977); cited favorably in Walker v. Texas Div., Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 2239, 2252 (2015). That ruling would not apply to insert or onsert requirements that did not include any political or ideological messages. It also might not apply to required inserts or onserts with ideological messages because they, unlike license plates, are not “mobile billboards” required on a “virtual necessity for most Americans” that is inescapably visible to large numbers of the public. 430 US. at 1435. It also appears that the ideological government speech on license plates struck down in Wooley v. Maynard was not clearly labeled as coming only from the government.

Johanns, 544 U.S. 550 (2005) at 557–59. See, also, Walker v. Texas Div., Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 2239, 2245 (2015). The 5–4 ruling in Walker v. Texas Div. split sharply as to whether state-issued license plates were government speech if, besides certain non-ideological government messages, they displayed different government-approved messages that expressed individual vehicle owners’ personal views that were not necessarily a government viewpoint (e.g., “Rather Be Golfing”). But government-required inserts or onserts would pass both the majority and the dissent opinions’ tests for government speech. They pass the majority’s test because: (a) product inserts and onserts have “long communicated messages from the [government” (e.g., in prescription and over-the-counter drugs); (b) government-required inserts and onserts are “often closely identified in the public mind with the [government];’” (c) the government “has sole control” over the content of the inserts or onserts; (d) inserts and onserts (or product packaging) are not “traditional public forums for private speech;” and (e) the inserts and onserts “are meant to convey and have the effect of conveying a government message” (e.g., would have indicia that their messages are owned and conveyed by the government). 135 S. Ct. at 2248–50, 52. Similarly, they qualify as government speech under the dissent’s test because: (a) governments have long used inserts and onserts “as a means of expressing a government message;” (b) there is no history of manufacturers allowing their products to be used as the site of inserts or onserts “that do not express messages that the [manufacturers] wish to convey;” (c) product packages can accommodate “only a limited number” of inserts or onserts; and (d) neither manufacturers nor consumers could pay to have certain messages included in the inserts or onserts. 135 S. Ct. at 2258–59, 2261.

See, e.g., Stephen D. Sugarman, Compelling Product Sellers to Transmit Government Public Health Messages” 29 J. OF LAW & POLITICS 557 (2014); and Micah L. Berman, Clarifying Standards for Compelled Commercial Speech, 50 WASHINGTON UNIV. J. OF LAW & POLICY 53 (2016). An argument might be made that requiring government-message inserts or onserts would impede the manufacturers’ ability to communicate to consumers through their own inserts or onserts. But manufacturers would not be prohibited from using their own inserts or onserts, and they could still use all other avenues of communication that are available to them to communicate with consumers. While having more than one insert or onsert might reduce consumer attention to one or both, it might also increase consumer awareness because of the novelty. In any case, the insert-onsert situation is quite different from required government warning labels on cigarette package that require a large percentage of the display area, thereby preventing the manufacturer from using that are for its own messaging (although even there manufacturers could increase their display space by increasing the overall size of the package).

See, e.g., Zauderer, 471 U.S. at 651. See, also, National Ass’n of Manufacturers v. S.E.C. 800 F.3d 518, 527 (DC Cir. 2015), finding that Zauderer “requires the disclosure to be of ‘purely factual and uncontroversial information’ about the good or service being offered” [quoting American Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, 760 F.3d 18, 27 (D.C. Cir. 2014), emphasis added]. That same opinion also discussed how opinions could be disguised as facts, and the difficulty in distinguishing between opinions and facts. 800 F.3d at 528.

National Ass’n of Manufacturers v. S.E.C., 800 F.3d 518, 528 (DC Cir. 2015).

National Ass’n of Manufacturers v. S.E.C., 800 F.3d 518, 528–31 (DC Cir. 2015). As the dissent noted, the compelled speech at issue (“not been found to be ‘DRC conflict free’”) communicated “truthful, factual information about a product to investors and consumers: it tells them that a product has not been found to be free of minerals originating in the DRC or adjoining countries that may finance armed groups.” 800 F.3d at 532. For more in the dissent on the meaning of “noncontroversial,” see 800 F.3d at 537–39. See, also, American Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, 760 F.3d 18, 27 (D.C. Cir. 2014) [finding compelled country-of-origin labeling factual and noncontroversial]; Evergreen Ass’n, Inc. v. City of New York, F.3d 233, note 6 [compelling pregnancy services centers to state the City’s treatment preferences or to mention controversial pregnancy-related services some centers oppose would be “controversial” if the Zauderer test applied]; CTIA-Wireless Ass’n v. City and County of San Francisco, 494 Fed.Appx. 752, 753–54 (9th Cir. 2012)[compelled commercial speech “controversial’ because it included City’s recommendations that could be interpreted as City’s opinion that using cell phones is dangerous, which had not been established]; Video Software Dealers Ass’n v. Schwarzenegger, 556 F.3d 950, 953, 966–67 (9th Cir. 2009)[compelled speech labeling video game as violent fails Zauderer test because it is controversial opinion not purely factual information]; New York State Restaurant Ass’n v. New York City Board of Health, 556 F.3d 114, 118 (2d Cir.2009)[compelled calorie counts in restaurant menus “factual and noncontroversial” despite objections that calorie amount disclosures should not be prioritized higher than other nutrient amounts]; Entertainment Software Ass’n v. Blagojevich, 469 F.3d 641, 652 (7th Cir. 2006)[compelled speech indicating that video game is “sexually explicit” not “factual or noncontroversial” because based on State’s opinion-based definition]. But see, also, Discount Tobacco City & Lottery Inc. v. U.S., 674 F.3d 509, note 8 (6th Cir. 2012)[stating that to apply the Zauderer test the compelled speech need not be noncontroversial but only accurate and factual].

R.J. Reynolds, 696 F.3d at 1211, 1216–17 (D.C. Cir. 2012). But see Discount Tobacco City & Lottery Inc. v. U.S., 674 F.3d 509, 526, 560–61 (6th Cir. 2012)[Finding that the Tobacco Control Act’s graphic health warnings requirement for cigarettes did not violate Zauderer, despite the fact that “there can be no doubt that the FDA’s choice of visual images is subjective, and that graphic, full-color images, because of the inherently persuasive character of the visual medium, cannot be presumed neutral.”].

R.J. Reynolds, 696 F.3d (D.C. Cir. 2012) at 1216–17 [majority opinion: “the provocatively named hotline cannot rationally be viewed as pure attempts to convey information to consumers” but is an “unabashed attempt[] to evoke emotion . . . and browbeat consumers into quitting”]; and at 1236 [dissent: “the number is prominently presented in imperative terms, directing consumers to ‘QUIT NOW.’ That command directly contradicts the companies’ desired message at the point of sale, thereby imposing a significant burden on their protected commercial speech.”] But these discussions of the 1–800-QUIT-NOW number also indicate that providing a phone number or website address that consumers could use to obtain information, with no exhortations to quit in the number, address or the associated sources, could be purely informational.

R.J. Reynolds 696 F.3d (D.C. Cir. 2012) at 1218 note 13.

R.J. Reynolds 696 F.3d (D.C. Cir. 2012) at 1236–37 (emphasis added).

Zauderer, 471 U.S. at 651 (1985). See, also, Milavetz, Gallop & Milavetz, P.A., 559 U.S. 229 (2010).

Zauderer 471 U.S. at 651(1985).

Zauderer 471 U.S. at 651(1985).

Milavetz, Gallop & Milavetz, P.A., 559 U.S. 229, 250 (2010).

In the R.J. Reynolds case, for example, the tobacco companies challenging the graphic health warnings did not dispute Congress’s authority to require health warnings on cigarette packs, did not challenge the substance of any of the health warning text in the graphic health warnings, and did not challenge the size or placement of the warning labels (e.g., top 50% of the front and back of the pack). R.J. Reynolds 696 F.3d (D.C. Cir. 2012) at 1211, 1215. In an earlier case, members of the tobacco industry did challenge the size and placement of the required cigarette warning labels and similar requirements for new non-graphic smokeless tobacco product warning labels (covering 30% of the front and back of the packaging), arguing that they were unduly burdensome because they would effectively overshadow and dominate their own commercial speech; but the 6th Circuit ruled against them. Discount Tobacco City & Lottery Inc. v. U.S., 674 F.3d 509, 530–31 (6th Cir. 2012).

See, e.g., Gerard S. Petrone, Tobacco advertising: The great seduction (1996) at 54–60, 147–48, 154–55; Arlene B. Hirschfelder, Encyclopedia on Smoking and Tobacco (1999) at 2–3.

To be prudent, this standard should also be applied to the content of any website or other external sources that the insert or onsert referred to or incorporated (e.g., by providing a website address or phone number).

Such clear attribution would ensure that consumers did not inaccurately think that the compelled speech messages were voluntarily coming from the manufacturer, thereby eliminating any risk of the government actually putting words into the manufacturers’ mouths

For example, any use of the 1–800-QUIT-NOW phone number in the inserts or onserts could be switched to only listing the actual numbers in the phone number.