Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether treatment with antidementia drugs is associated with reduced mortality in older patients with different mortality risk at baseline.

Design:

Retrospective.

Setting:

Community-dwelling.

Participants:

A total of 6818 older people who underwent a Standardized Multidimensional Assessment Schedule for Adults and Aged Persons (SVaMA) evaluation to determine accessibility to homecare services or nursing home admission from 2005 to 2013 in the Padova Health District, Italy were included.

Measurements:

Mortality risk at baseline was calculated by the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on information collected with the SVaMA. Participants were categorized to have mild (MPI-SVaMA-1), moderate (MPI-SVaMA-2), and high (MPI-SVaMA-3) mortality risk. Propensity score-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of 2-year mortality were calculated according to antidementia drug treatment.

Results:

Patients treated with antidementia drugs had a significant lower risk of death than untreated patients (HR 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–0.92 and 0.56; 95% CI 0.49–0.65 for patients treated less than 2 years and more than 2 years treatment, respectively). After dividing patients according to their MPI-SVaMA grade, antidementia treatment was significantly associated with reduced mortality in the MPI-SVaMA-1 mild (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.92) and MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate risk (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.40–0.91, matched sample), but not in the MPI-SVaMA-3 high risk of death.

Conclusions:

This large community-dwelling patient study suggests that antidementia drugs might contribute to increased survival in older adults with dementia with lower mortality risk.

Keywords: Dementia, comprehensive geriatric assessment, multidimensional prognostic index (MPI), mortality, frailty, antidementia drugs

In 2013, official death certificates recorded 84,767 deaths from Alzheimer disease (AD), making AD the sixth leading cause of mortality in the United States and the fifth leading cause of death in Americans aged older than 65 years.1

Some factors have been associated with a decrease in AD survival.2–5 On the contrary, symptomatic antidementia drugs, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) (donepezil, galantamine, and riva-stigmine) and the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist (memantine), can have some beneficial effects in people with AD, such as delay nursing home placement alone 6–8 or in combination9 and may reduce mortality for patients living in nursing homes and in the community.10,11 However, these medications are associated with several side effects such as cardiovascular12 and gastrointestinal13 events. Therefore, applying the correct prescription indications and identifying patients with AD potentially benefiting from antidementia therapy is a priority.

Decision-making for therapeutic options in older patients with dementia is a major challenge for health practitioners, particularly in frail older patients. In fact, frailty is associated with a greater risk for adverse health-related outcomes14,15 or cognitive-related outcomes.16 Mortality risk stratification in frail older patients should be based on information on comorbidity and functional status,17 possibly using a multidimensional Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) that integrates information of several domains of health and function.18 Recently, a Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) derived from a standardized CGA has been developed and validated for mortality risk assessment in several independent cohorts of hospitalized19 and community-dwelling older adults20 with acute or chronic diseases, including older adults with dementia.21,22

The main aim of the present observational study was to estimate the all-cause mortality risk linked to antidementia drug use in frail older community-dwelling persons with dementia with a different grade of mortality risk.

Methods

Study Population

This was a retrospective observational study conducted according to the World Medical Association’s 2008 Declaration of Helsinki, the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.23 All consecutive community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and older who underwent a CGA-based multidimensional assessment according to the Standardized Multidimensional Assessment Schedule for Adults and Aged Persons (Scheda per la Valutazione Multidimensionale delle persone adulte e Anziane) (SVaMA)20 from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2013 were screened for inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosis of dementia according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision 290 and subgroups or according to the main diagnosis record P70 of the SVaMA; and (2) a SVaMA evaluation within 2 months from the date of the first registration of the dementia diagnosis in the database. The Institutional Review Board of the Social and Healthcare Local Unit (Unità Locale Socio Sanitaria, ULSS) 16, Padova, Italy approved this retrospective observational study. Informed consent was given by participants who underwent SVaMA evaluation and/or their proxies for their clinical records to be used in clinical studies. All patient records and information were anonymized and deidentified prior to the analysis.

Main Exposure

Antidementia drug users were defined as participants with dementia using donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, with or not memantine. The “enrollment” was defined as the first prescription that succeeded the date of the registration of the dementia diagnosis. According to the Italian law, donepezil, galantamine, and riva-stigmine are given to patients with a diagnosis of AD and a Mini-Mental State Examination score between 21 and 26, whereas memantine is allowed only if the Mini-Mental State Examination score is between 10 and 20. These medications are prescribed by specialists trained in dementia and monitored by the Italian National Healthcare System. For nonusers, the “enrollment” was defined as the date of the SVaMA completion that succeeded the date of the first registered dementia diagnosis in the database. If the date of SVaMA completion preceded the date of the diagnosis registration, the time interval between these dates was lower than 2 months. Our cohort was linked to the Pharmaceutical Prescription database of the Azienda ULSS 16 Padova to extract the individual medication use. Drug prescriptions were determined according to the anatomic therapeutic chemical codes.

Main Outcome

Participants were followed for a mean follow-up of 2.2 ± 2.1 years. Vital status was assessed by consulting the Registry Offices of the cities in which the patients were residents at the time of the evaluation. Dates of death were identified from death certificates. All data regarding the evaluations were extracted from the Administrative Repository Database of the ULSS 16, Padova, Italy.

The MPI Based on the SVaMA

The SVaMA is the officially recommended multidimensional assessment schedule used by the health personnel of the National Healthcare System to perform a multidimensional assessment in community-dwelling older persons introduced by the Veneto Regional Health System since 2000 to establish accessibility to some healthcare resources (homecare services or nursing home admission).20 For the purposes of our study, we included people attending nursing homes only because this is the most common reason of accessing SVaMA.20

To calculate the MPI, the following domains of the SVaMA were considered: (1) age, (2) sex, (3) main diagnosis, (4) nursing care needs (VIP) evaluated according to a validated numeric scale; (5) cognitive status (VCOG), evaluated by the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ); (6) the pressure sores risk (VPIA), evaluated by the Exton-Smith Scale; (7) the activities of daily living (VADL) and (8) mobility (VMOB) evaluated by the Barthel index; and (9) social support (VSOC), evaluated by a numeric scale of 16 items that explores the presence of a support network during the day and the night.

The MPI-SVaMA was expressed as a continuous value from 0 (lower risk) to 1.0 (higher risk of mortality). The recursive partition and amalgamation algorithm was used to identify subgroups of patients at different risks for mortality.20 The following cut-offs were estimated for the normalized MPI-SVaMA 1-year mortality prediction: 0–0.33 (MPI-SVaMA-1, mild risk), 0.34–0.47 (MPI-SVaMA-2, moderate risk), and 0.48–1.0 (MPI-SVaMA-3, severe risk). Further information on reliability, accuracy, calibration, and validation of the MPI based on the SVaMA has been described in detail elsewhere.20

Statistical Analysis

General characteristics were reported as frequencies (percentages) and mean ± standard deviation (SD), with median and quartiles (for highly asymmetric distributions), for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Mortality incidence rates were computed as the number of deaths per person-year. Comparisons across MPI- SVaMA grades were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for singly ordered contingency tables, and linear by linear association test, for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

To study the association between the treatment with antidementia drugs with mortality risk across MPI-SVaMA grades, Cox proportional hazard univariate regression models were applied for each MPI- SVaMA grade subgroup, and results were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Kaplan-Meier method was also used to estimate nonparametric survival distributions. To control for possible confounding effects, the propensity score methodology was applied.24 In the present study, logistic regression models were used to predict the probability (propensity score) to be treated with antidementia drugs according to the following available variables with a potentially confounding effect on mortality: MPI-SVaMA index (treated as continuous variable), presence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and use of antipsychotic drugs. Separate logistic models were run for each MPI-SVaMA grade sub-group. Multivariate adjustment by the propensity score was then applied including the propensity score in the Cox regression model along with the antidementia treatment for each MPI-SVaMA grade subgroup.

To further explore the association between treatment with antidementia drugs and mortality risk across MPI-SVaMA grades, a sub-sample of treated and untreated patients homogeneous with respect to potentially confounding variables was then created for each MPI grade subgroup by a 1:1 matching algorithm. The algorithm identified a unique matched control for each treated patient according to sex, age, presence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, use of antipsychotic drugs, and their values of the estimated propensity score. As these matched samples did not consist of independent observations, marginal survival Cox models based on an estimating equations approach to obtain the proper standard error estimates were used. P values assessing the presence of a heterogeneous effect of antidementia treatment between MPI-SVaMA risk subgroups were also calculated and reported. Two-sided alternatives with a significance level of α = 0.05 were considered for all the tests. The analyses were performed using StatXact-5 (Cytel Software, Cambridge, MA), SAS Release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and R version 3.2.1 (R Project, Geneva, Switzerland).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

The study population included 6818 patients, 1966 men (28.6%) and 4799 women (70.4%) with a mean age of 84.1 ± 6.9 years.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients according to their MPI-SVaMA grade: 4194 patients (61.5%) were in the MPI-SVaMA-1 mild-risk group, 2215 patients (32.5%) in the MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate-risk group, and 409 patients (6.0%) in the MPI-SVaMA-3 severe-risk of mortality group. Patients with higher MPI-SVaMA values (MPI-SVaMA-3, severe risk) were more likely to be male (P value < .0001) and older (P value < .0001) as well as of having significantly higher VADL, VCOG, VIP, VMOB, and VPIA scores (P value < .0001 for all comparisons), and particularly for Nursing Care Needs and Pressure sore risks. Finally, people with MPI-SVaMA-3 severe risk had a higher prevalence of concomitant diseases (P value < .0001), except hypertension than patients at lower risk of mortality (MPI-SVaMA-1 and −2 subgroups).

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Older Patients With Dementia Disease According to MPI-SVaMA Grade

| Total | MPI-SVaMA-1 Mild Risk |

MPI-SVaMA-2 Moderate Risk |

MPI-SVaMA-3 Severe risk |

P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n, %) | 6818 | 100 | 4194 | 100 | 2215 | 100 | 409 | 100 | |

| Sex* (n, %): | |||||||||

| Male | 1966 | 28.8 | 938 | 22.4 | 790 | 35.7 | 238 | 58.2 | <.0001 |

| Female | 4799 | 70.4 | 3210 | 76.5 | 1418 | 64.0 | 171 | 41.8 | |

| VADL (mean ± SD) | 42.7 ± 18.3 | 33.9 ± 17.8 | 56.6 ± 5.9 | 58.1 ± 6.3 | <.0001 | ||||

| VCOG (mean ± SD) | 7.8 ± 2.5 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 8.6 ± 2.1 | 9.0 ± 2.1 | <.0001 | ||||

| VIP (mean ± SD, median, Q3) | 3.5 ± 6.4 (0, 5) | 0.9 ± 2.7 (0, 0) | 6.0 ± 6.4 (5, 10) | 17.4 ± 9.1 (10, 20) | <.0001 | ||||

| VMOB (mean ± SD) | 26.8 ± 13.8 | 19.7 ± 13.0 | 38.0 ± 3.8 | 38.9 ± 4.4 | <.0001 | ||||

| VPIA (mean ± SD, median, Q3) | 3.9 ± 5.8 (0, 10) | 0.6 ± 2.4 (0, 0) | 8.3 ± 4.9 (10, 10) | 13.5 ± 7.4 (10, 15) | <.0001 | ||||

| VSOC (mean ± SD) | 167.0 ± 66.2 | 161.4 ± 66.5 | 176.9 ± 64.2 | 169.9 ± 67.5 | <.0001 | ||||

| Concomitant diseases (n, %): | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1992 | 29.2 | 1120 | 26.7 | 704 | 31.8 | 168 | 41.1 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1215 | 17.8 | 685 | 16.3 | 430 | 19.4 | 100 | 24.4 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 4136 | 60.7 | 2513 | 59.9 | 1363 | 61.5 | 260 | 63.6 | n.s. |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 5231 | 76.7 | 3089 | 73.7 | 1784 | 80.5 | 358 | 87.5 | <.0001 |

| Age at SVaMA evaluation (y): | 84.1 ± 6.9 | 82.8 ± 6.9 | 86.3 ± 6.4 | 86.4 ± 6.7 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 85 (80,89) | 83 (78,87) | 87 (82,91) | 87 (82,91) | |||||

| Follow-up time (y), (n, %): | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.7 (0.5, 3.4) | 2.3 (0.9, 4.0) | 0.9 (0.2, 2.5) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) | |||||

| Mortality (n, deaths; n, deaths per person-y): | |||||||||

| At 2 y | 2596 | 1.60 | 1052 | 1.21 | 1207 | 1.83 | 337 | 3.54 | <.0001 |

| Total | 3643 | 0.68 | 1828 | 0.49 | 1466 | 0.97 | 349 | 2.51 | <.0001 |

| Use of antipsychotic drugs (n, %): | 2826 | 41.5 | 1849 | 44.1 | 827 | 37.3 | 150 | 36.7 | <.0001 |

| Use of antidementia drugs (n, %): | 1364 | 20.0 | 1063 | 25.3 | 226 | 10.2 | 75 | 18.3 | <.0001 |

| Duration of treatment with antidementia drugs (y): | |||||||||

| ≤2 y | 713 | 10.5 | 536 | 12.8 | 137 | 6.2 | 40 | 9.8 | <.0001 |

| >2 y | 651 | 9.5 | 527 | 12.6 | 89 | 4.0 | 35 | 8.6 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 2.0 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 2.0 | |||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.9 (0.8, 3.5) | 2.0 (0.8, 3.7) | 1.5 (0.5, 2.8) | 1.7 (0.6, 3.4) | |||||

n.s., not significant; Q1, Q3, first and third quartile; SD, standard deviation; VADL, activities of daily living (Barthel Index); VCOG, visit cognitive status; VIP, nursing care needs; VPIA, pressure sores risk; VMOB, mobility (Barthel Index); VSOC, social support.

Overall, 1364 patients (20% of the total study population with dementia) were treated with antidementia drugs. Patients treated with antidementia drugs were more frequently in the MPI-SVaMA-1 group than in the moderate and severe mortality risk groups. The three MPI-SVaMA groups showed slight, but significant differences in the duration of treatment (P value < .0001): for patients with mild or severe risk, the mean duration of treatment was around 2.5 years, whereas patients with moderate risk had a mean treatment duration of 2 years.

Factors Associated with Mortality

As expected, patients with higher MPI-SVaMA grade were significantly at higher risk of mortality: the estimated HRs (95% CI) for patients in MPI-SVaMA-2 and MPI-SVaMA-3 were 2.14 (1.99–2.30) and 5.52 (4.91–6.21) compared with patients in MPI-SVaMA-1 (Table 2). Moreover, treatment with antidementia drugs was associated with significant lower mortality compared with no treatment. The estimated HRs for the groups of patients treated for less than 2 years and for more than 2 years with antidementia drugs were 0.82 (95% CI 0.73–0.92) and 0.56 (95% CI 0.49–0.65), respectively.

Table 2.

Proportional Hazard Multivariate Regression Model on Possible Factors Influencing Mortality Risk in Community-Dwelling Older Patients With Dementia

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without propensity score matching | |||

| No antidementia treatment | 1 | ||

| Duration of treatment ≤2 y | 0.82 | (0.73, 0.92) | <.0001 |

| Duration of treatment >2 y | 0.56 | (0.49, 0.65) | <.0001 |

| MPI-SVaMA-1 mild risk of mortality | 1 | ||

| MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate risk of mortality | 2.14 | (1.99, 2.30) | <.0001 |

| MPI-SVaMA-3 severe risk of mortality | 5.52 | (4.91, 6.21) | <.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.13 | (1.05, 1.22) | .0014 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.94 | (0.86, 1.02) | .1318 |

| Hypertension | 1.01 | (0.94, 1.09) | .7666 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.21 | (1.10, 1.32) | <.0001 |

| Use of antipsychotic drugs | 0.86 | (0.81, 0.92) | <.0001 |

| With propensity score matching | |||

| No antidementia treatment | 1 | ||

| Duration of treatment ≤2 y | 0.83 | (0.74, 0.93) | .0019 |

| Duration of treatment >2 y | 0.56 | (0.49, 0.65) | <.0001 |

| MPI-SVaMA-1 mild risk of mortality | 1 | ||

| MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate risk of mortality | 2.19 | (2.04, 2.35) | <.0001 |

| MPI-SVaMA-3 severe risk of mortality | 5.68 | (5.05, 6.38) | <.0001 |

To further explore the association of the antidementia treatment and the MPI-SVaMA grade on mortality, a second proportional hazard multivariate regression model was considered, collapsing all the factors potentially associated with the mortality risk into a propensity score The significant association between antidementia drug use and lower mortality rates as well as the association between increasing MPI-SVaMA grades and increasing mortality were confirmed (Table 2).

Antidementia Drug Use and Survival Across MPI-SVaMA Grades

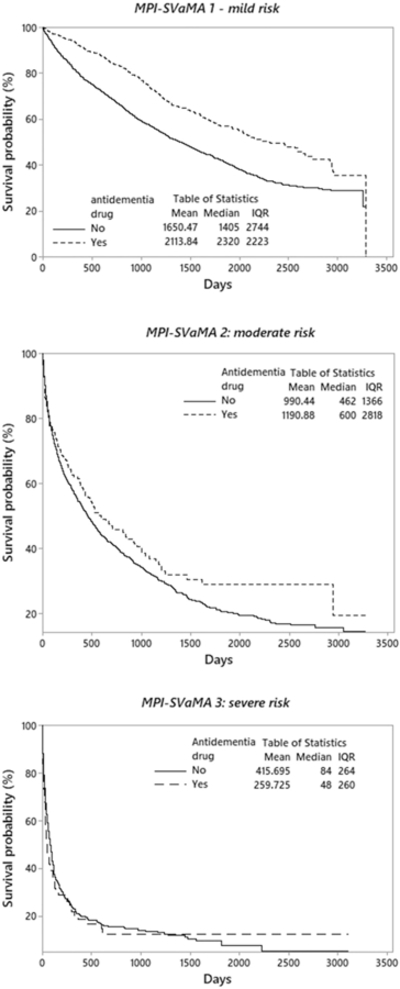

The survival distribution estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method for each MPI-SVaMA grade subgroup (Figure 1) showed a significant higher survival trend for patients treated with antidementia drugs compared with untreated patients both in the MPI-SVaMA-1 group (median survival time: 6.4 vs 3.8 years) and MPI-SVaMA-2 group (median survival time: 1.6 vs 1.3 years). No effect was observed in the MPI-SVaMA-3 group.

Fig. 1.

Nonparametric survival plot (Kaplan-Meier method) for treatment with anti-dementia drugs in total samples.

After adjusting for the propensity scores, the use of antidementia drugs was associated with a lower mortality rate in people at mild risk (MPI-SVaMA-1) (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.61–0.79) and at moderate risk of death (MPI-SVaMA-2) (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.71–1.02), whereas this association was not evident in MPI-SVaMA-3 group (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.76–1.36) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Antidementia Drug Use With Mortality Risk Across MPI-SVaMA Grades

| Total Samples | Deaths | Patients | Unadjusted Univariate Models | Multivariate Models Adjusted for Propensity Score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |||

| Total sample | ||||||||

| MPI-SVaMA-1 mild risk of mortality | ||||||||

| No treatment | 1508 | 3131 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Antidementia drugs | 320 | 1063 | 0.57 | (0.51, 0.64) | <.0001 | 0.69 | (0.61, 0.79) | <.0001 |

| MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate risk of mortality | ||||||||

| No treatment | 1338 | 1989 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Antidementia drugs | 128 | 226 | 0.85 | (0.71, 1.02) | .0853 | 0.85 | (0.71, 1.02) | .0793 |

| MPI-SVaMA-3 severe risk | ||||||||

| No treatment | 287 | 334 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Antidementia drugs | 62 | 75 | 1.14 | (0.87, 1.51) | .3409 | 1.02 | (0.76, 1.36) | .9159 |

| Matched samples | ||||||||

| MPI-SVaMA-1 mild risk of mortality | ||||||||

| No treatment | 130 | 280 | 1 | |||||

| Antidementia drugs | 89 | 280 | 0.71 | (0.54, 0.92) | .0108 | |||

| MPI-SVaMA-2 moderate risk of mortality | ||||||||

| No treatment | 55 | 78 | 1 | |||||

| Antidementia drugs | 40 | 78 | 0.61 | (0.40, 0.91) | .0169 | |||

| MPI-SVaMA-3 severe risk of mortality | ||||||||

| No treatment | 16 | 19 | 1 | |||||

| Antidementia drugs | 17 | 19 | 1.04 | (0.52, 2.06) | .9169 | |||

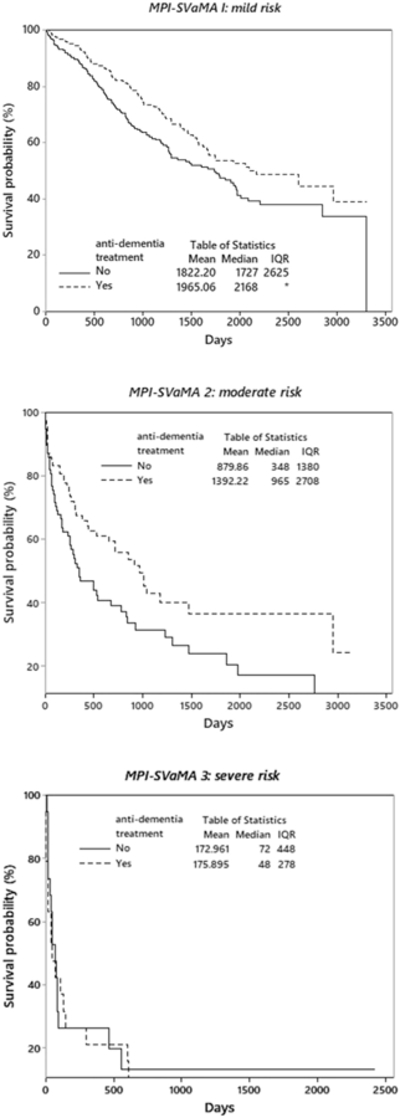

To further explore the association between antidementia treatment and mortality across MPI-SVaMA grades, a survival analysis by Kaplan-Meir method and marginal Cox regression models was applied to the matched subsamples related to the 3 MPI-SVaMA grades (Table 3). A significant association between antidementia drug use and lower mortality was observed in treated patients in the mild risk MPI-SVaMA-1 matched sample (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.92) and in the moderate risk MPI-SVaMA-2 matched sample (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.40–0.91), whereas the severe risk MPI-SVaMA-3 matched sample showed no significant association (HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.52–2.06) (Table 3). As shown in Figure 2, the MPI-SVaMA-1 matched sample showed a median survival time of 5.9 years for treated patients vs 4.7 years for untreated patients, and MPI-SvaMA-2 matched sample reported a median survival time of 2.6 years for treated patients vs 1.3 years for untreated patients. The MPI-SVaMA-3 matched sample confirmed a not significant association between antidementia drug use and survival.

Fig. 2.

Nonparametric survival plot (Kaplan-Meier method) for treatment with anti-dementia drugs in matched samples.

Discussion

In this real-world observational study of a large cohort of community-dwelling persons with dementia and a very old age (median age 85 years), a more favorable mortality trend for patients treated with antidementia drugs with respect to untreated patients was found in the MPI-SVaMA-1 (mild risk) and MPI-SVaMA-2 (moderate risk) compared with MPI-SVaMA-3 (high risk of death) group. These findings suggest a prolonged survival linked to antidementia drug use in older adults at lower risk of mortality.

Survival after diagnosis of dementia varies considerably, depending on numerous factors and their complex interactions. A systematic review comparing mortality rates in dementia with estimated life expectancies in the general population suggested that relative loss of life expectancy decreases with age at diagnosis and also depends on sex, dementia subtype, and severity stage.25 In the present study, use of antidementia drugs appears associated with increased survival, albeit only in the groups with lower multidimensional impairment and consequently at lower mortality risk. Of the entire patient sample, only 20% used antidementia drugs, a prevalence similar to that reported in a large sample of European nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment.26 Even if some studies showed that antidementia drugs can delay nursing home placement,6–8 the effect on mortality is still uncertain. In fact, while tacrine, one of the first medications used for treating AD, prolonged survival in nursing home residents with dementia,27 similar mortality incidence between treated and untreated groups was found in a pooled analysis of 3 clinical trials on donepezil treatment in severe AD.28 More recently, AChEI use has been associated with decreased institutionalization, with no effect on life expectancy.8.Furthermore, AChEI alone or AChEI plus memantine use were not associated with mortality.9 Conversely, a cohort study in 7073 patients with AD in the Swedish Dementia Registry suggested that AChEIs were associated with a lower risk of death and myocardial infarction,29 confirming a positive effect of donepezil as proposed by another Japanese retrospective observational study.30 In a large cohort of patients from early stages of AD prospectively followed over 6 years, AChEI use was associated with longer time to reaching functional endpoints, and death and memantine use was associated with delayed mortality.11 On the contrary, in other large observational studies, cumulative antidementia drugs3 or memantine alone31 did not prolong overall survival in patients with AD, and memantine was also associated with greater risk of all-cause mortality in the Medicare and Danish cohorts,32 probably because memantine is a second-step medication for the treatment of AD.

In our large cohort of older adults with dementia, a prolonged survival linked to antidementia drugs was found only in patients with lower multidimensional impairment. It is noteworthy that participants in the MPI-SVaMA-2 (moderate risk group) treated with anti-dementia medications showed a significant lower risk of mortality after using a matching approach between treated and nontreated patients. These findings suggest that some confounders present at baseline could have nullified the protective association between the use of antidementia drugs and death and that future specific research is needed. In this regard, our study adds something novel about the timing of discontinuation of antidementia agents, suggesting that multidimensional impairment is one of the most important factors in determining whether to suspend these agents or not. In fact, in clinical practice, the main reasons for administration of these drugs is to improve cognitive and/or disability, and sometimes for the management of behavioral symptoms of dementia,33 whereas the impact of these medications on mortality risk is often not considered. Another important point for whether to discontinue these drugs or not is that if these medications would improve the quality of life in people affected by AD. In a systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2006, it seems that these medications could have a favorable effect on quality of life.34 However, the data are still limited to a few studies; validated tools for assessing the quality of life in these patients were not used34 suggesting that other studies are needed to explore this subject.

The MPI has been proven to be well calibrated in discriminating mortality risk rates because of its clinimetric properties35 and that it is based on calculations from a CGA.18 The MPI-SVaMA domain variables included multidimensional and integrated information on health-related, functional, cognitive, and social status of patients.20 This approach identified frailty as a composition of multisystemic changes occurring in older persons that may determine an increased risk for adverse health outcomes, including death.35 The potential for reversibility of frailty and its different phenotypes suggests that these clinical constructs may be important secondary targets for the prevention of dependency and other negative outcomes in older age, including those that are cognitively related.16 In fact, a recent and growing body of literature suggests that frailty and poor cognitive status are strictly associated.32,36 Therefore, investigating survival in frail demented persons in relation to antidementia drug use may be important to prescribe these medications appropriately. The mechanisms underlying the effect of AChEI on mortality rates need further investigation and might involve the cardiovascular system.37 AChEI released from vagal nerve activate local acetylcholine synthesis in cardiomyocytes in a paracrine way with possible cardioprotection effect.38 Moreover, in vitro experiments suggested an anti-inflammatory effect of AChEI on atherosclerosis.39 As inflammation is important for AD and dementia,40 a possible modulatory effect of AChEI on inflammation might result in decreased mortality rates in patients treated with antidementia drugs. Unfortunately, the present study was not powered to explore the different causes of death driven by antidementia drugs, and further studies are needed to address this issue.

Very recently, the MPI-SVaMA has been implemented in older people to evaluate whether a different individual prognostic profile was associated with different mortality rates after treatment for specific disorders (ie, statins in older patients with diabetes mellitus41 or coronary artery disease42 as well as anticoagulants in older patients with atrial fibrillation).43 These studies suggested that full access to prognostic information derived from CGA-based predictive tools better equips physicians to make clinical decisions aligned with their patients’ needs in terms of safety and efficacy.18 Furthermore, the presence of the propensity score in our analytical approach did not lead to the observation of variations both in the estimated coefficients and in their standard errors with respect to the model including all the covariates, suggesting that the utilization and correct interpretation of the MPI-SVaMA score are able to reflect the complexity of patient clinical profiles.

We must also acknowledge some limitations of the study. First, we considered the impact of different factors including antidementia and antipsychotic drugs only in terms of reduced all-cause mortality, not considering different causes of deaths. Second, the present findings were observational and originated from administrative data. Further-more, a cumulative drug exposure to antidementia drugs (AChEIs and memantine) was used which does not exclude drug-specific associations with survival; however, in December 2014, the Food Drug Administration approved the sixth drug for AD, which combines 2 existing Food Drug Administration-approved AD drugs (donepezil and memantine) for moderate to severe disease.1 Finally, because the follow-up of these patients was limited to 2 years, we cannot exclude that significant differences in effectiveness among patients with different mortality risk could emerge with longer follow-up. Finally, important confounders in the association between the use of AChEIs and mortality (eg, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD) were not included in our analyses.

In conclusion, in this large cohort of community-dwelling frail adults with dementia and a very old age, a significant association between antidementia drug use and lower all-cause mortality was found only in the lower mortality risk group during the 2-year follow-up period. This finding suggests a prolonged survival linked to antidementia drug use in older frail patients with dementia and low multidimensional impairment. Future randomized controlled trials, including a consistent part of people with different degrees of frailty, are needed to validate the present observations.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the MPI_Age European project co-funded by the Consumers, Health, Agriculture, and Food Executive Agency (CHA-FEA) in the frame of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing Second Health Program 2008e2013. The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the above mentioned authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. The funding agencies had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The study was based on administrative data sets, and the participants were not identifiable to the authors.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Association Association. 2016. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer Dementia 2016;12:459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambassi G, Lapane KL, Landi F, et al. Gender differences in the relation between comorbidity and mortality of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology (SAGE) Study Group. Neurology 1999;53:508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rountree SD, Chan W, Pavlik VN, et al. Factors that influence survival in a probable Alzheimer disease cohort. Alzheimer Res Ther 2012;4:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueki A, Shinjo H, Shimode H, et al. Factors associated with mortality in patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: A five-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moritz DJ, Fox PJ, Luscombe FA, Kraemer HC. Neurological and psychiatric predictors of mortality in patients with Alzheimer disease in California. Arch Neurol 1997;54:878–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wimo A, Winblad B, Stoffler A, et al. Resource utilisation and cost analysis of memantine in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Phar-maco Economics 2003;21:327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wisniewski S, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment alters the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:310–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wahed AS, et al. Long-term effects of the concomitant use of memantine with cholinesterase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:600–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasper MC, Ott BR, Lapane KL. Is donepezil therapy associated with reduced mortality in nursing home residents with dementia? Am J Geriatr Pharmac-other 2005;3:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu CW, Livote EE, Scarmeas N, et al. Long-term associations between cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine use and health outcomes among patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dementia 2013;9:733–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howes LG. Cardiovascular effects of drugs used to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Safety 2014;37:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soysal P, Isik AT, Stubbs B, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are associated with weight loss in older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:1368–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England: ) 2013;381:752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panza F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, et al. Targeting cognitive frailty: Clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;47:793–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, et al. Prognostic indices for older adults: A systematic review. JAMA 2012;307:182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilotto A, Cella A, Pilotto A, et al. Three decades of comprehensive geriatric Assessment: Evidence coming from different healthcare settings and specific clinical conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:e1–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilotto A, Ferrucci L, Franceschi M, et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res 2008; 11:151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilotto A, Gallina P, Fontana A, et al. Development and validation of a Multi-dimensional Prognostic Index for mortality based on a standardized Multidimensional Assessment Schedule (MPI-SVaMA) in community-dwelling older subjects. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilotto A, Sancarlo D, Panza F, et al. The multidimensional prognostic index (MPI), based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized older patients with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2009;18:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallucci M, Battistella G, Bergamelli C, et al. Multidimensional prognostic index in a cognitive impairment outpatient setting: Mortality and hospitalizations. The Treviso Dementia (TREDEM) study. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;42: 1461–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodaty H, Seeher K, Gibson L. Dementia time to death: A systematic literature review on survival time and years of life lost in people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onder G, Liperoti R, Foebel A, et al. Polypharmacy and mortality among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment: Results from the SHEL-TER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:450.e7–450.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ott BR, Lapane KL. Tacrine therapy is associated with reduced mortality in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winblad B, Black SE, Homma A, et al. Donepezil treatment in severe Alzheimer’s disease: A pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2577–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordstrom P, Religa D, Wimo A, et al. The use of cholinesterase inhibitors and the risk of myocardial infarction and death: A nationwide cohort study in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2585–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meguro K, Kasai M, Akanuma K, et al. Donepezil and life expectancy in Alzheimer’s disease: A retrospective analysis in the Tajiri Project. BMC Neurol 2014;14:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidal JS, Lacombe JM, Dartigues JF, et al. Memantine therapy for Alzheimer disease in real-world practice: An observational study in a large representative sample of French patients. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2008;22: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment A review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12: 840–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien JT, Burns A. Clinical practice with antidementia drugs: A revised (second) consensus statement from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2011;25:997–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda A, Loveman E, Clegg A, et al. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine on cognition, quality of life and adverse events in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21: 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilotto A, Sancarlo D, Daragjati J, Panza F. Perspective: The challenge of clinical decision-making for drug treatment in older people. The role of multidimensional assessment and prognosis. Front Med 2014;1:1–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima G, Taniguchi Y, Iliffe S, Walters K. Frailty as a predictor of Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, and all dementia among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monacelli F, Rosa G. Cholinesterase inhibitors: Cardioprotection in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;42:1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakinuma Y, Akiyama T, Sato T. Cholinoceptive and cholinergic properties of cardiomyocytes involving an amplification mechanism for vagal efferent effects in sparsely innervated ventricular myocardium. FEBS J 2009;276: 5111–5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosas-Ballina M, Tracey KJ. Cholinergic control of inflammation . J Intern Med 2009;265:663–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White CS, Lawrence CB, Brough D, Rivers-Auty J. Inflammasomes as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland: ) 2017;27: 223–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilotto A, Panza F, Copetti M, et al. Statin treatment and mortality in community-dwelling frail older patients with diabetes mellitus: A retrospective observational study. PloS One 2015;10:e0130946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pilotto A, Gallina P, Panza F, et al. Relation of statin use and mortality in community-dwelling frail older patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2016;118:1624–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilotto A, Gallina P, Copetti M, et al. Warfarin treatment and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older adults with atrial fibrillation: A retrospective observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:1416–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]