Abstract

In Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), by contrast to sporadic cerebral small vessel disease related to age and hypertension, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) are frequently observed in the white matter of anterior temporal poles, external capsules, and superior frontal regions. Whether these WMH (specific WMH) differ from those observed in other white matter areas (nonspecific WMH) remains unknown. Twenty patients were scanned to compare specific and nonspecific WMH using high-resolution images and analyses of relaxation times (T1R: longitudinal relaxation time and T2*R: effective transversal relaxation time). Specific WMH were characterized by significantly longer T1R and T2*R (T1R: 2309 ± 120 ms versus 2145 ± 138 ms; T2*R: 40 ± 5 ms versus 35 ± 5 ms, p < 0.001). These results were not explained by the presence of dilated perivascular spaces found in the close vicinity of specific WMH. They were not either explained by the normal regional variability of T1R and T2*R in the white matter nor by systematic imaging artifacts as shown by the study of 17 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Our results suggest large differences in water content between specific and nonspecific WMH in CADASIL, supporting that mechanisms underlying WMH may differ according to their location.

Keywords: CADASIL, cerebral small vessel disease, dilated perivascular spaces, relaxometry, white matter hyperintensities

Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) of presumed vascular origin are a hallmark of both sporadic cerebral small vessel diseases (SVD) related to age and hypertension and CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy), a monogenic SVD caused by mutations of the NOTCH3 gene.1 By contrast to sporadic SVD, WMH are frequently observed in the white matter of anterior temporal poles, external capsules, and superior frontal gyri in CADASIL2,3 (specific WMH). In other white matter areas, WMH can be seen either in CADASIL or in sporadic SVD (nonspecific WMH).

WMH are generally considered to result from hypoperfusion although the underlying pathological picture may be more complex.4 In SVD, WMH first appear in deep brain areas where the microvasculature is less redundant, and further expand toward subcortical areas.5 The presence of specific WMH in CADASIL would result from a larger burden of WMH.

However, several elements question the mechanisms of WMH in CADASIL. For instance, while the extent of WMH was repeatedly found associated with gait disturbances, disability, and cognitive alterations in sporadic forms,6 their clinical impact in CADASIL is unclear.7,8 Additionally, while the burden of WMH is generally associated with brain atrophy in sporadic SVD,9 CADASIL patients with extensive WMH have the largest brain volumes10 and young patients with WMH at the early clinical stage of the disease show larger amounts of white matter than age- and sex-matched controls.11

As postmortem studies of white matter alterations are scarce in CADASIL12–14 and by definition performed at the latest stages of the disease, regional differences in white matter pathology might have been missed. In the present study, we hypothesized that the microstructure of specific and nonspecific WMH in CADASIL may differ.

In vivo, local brain structure can be probed by specific techniques such as relaxometry that estimate the local values of relaxation times in milliseconds (T1R: longitudinal relaxation time, T2*R: effective transversal relaxation time) which are quantitative measures tightly related to tissue composition and water content. However, given the limited resolution of these approaches, additional high-resolution MRI is necessary for a comprehensive interpretation of these quantitative data.

We studied high-resolution MRI scans and relaxometry images obtained at 7 T to identify differences in anatomical and/or microstructural alterations between specific and nonspecific WMH in CADASIL. Age- and sex-matched controls with virtually no WMH underwent the same imaging protocol to ensure that potential differences between specific and nonspecific WMH would not be driven by imaging artifacts nor by the normal regional variability of relaxation times within the white matter.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty genetically confirmed CADASIL patients with preserved global cognitive abilities (MMSE score ≥24) and without significant disability (modified Rankin’s scale ≤1) and 17 age- and sex-matched controls followed in a prospective cohort study15,16 were evaluated with a specific MRI protocol including relaxometry acquisitions and high-resolution anatomical scans obtained at 7 T. All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in the study and the protocol was validated by a local ethics committee (Ile de France VII, No. CPP09-012). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (revised 1983) and with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

MRI acquisitions were performed at NeuroSpin (CEA, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) both on a 7 and a 3 T MRI scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 32-channel head coil for reception purposes from, respectively, Nova Medical (We, MA, USA) and Siemens Healthcare. The 7 T exam comprised a variable flip angle whole-brain T1R mapping acquisition including two 3D gradient-echo sequences (TE = 3.06 ms, TR = 14 ms, BW = 250 Hz/pixel, pixel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) with two different flip angles (FA = 5° and 20°). It also included a B1 + map to assess RF transmission inhomogeneities.17 In our case, an actual flip angle sequence18 was used with the same coverage as gradient-echo acquisitions and with the following parameters: TE = 3.06 ms, TR1 + TR2 =130 ms, TR1/TR2 = 5, BW = 1560 Hz/pixel, pixel size = 4 × 4 × 4 mm3. T1R map was reconstructed considering perfect spoiling and using spatial FA data extracted from the B1 map. The protocol also included a 3D multi-gradient-echo sequence (TE varying from 1.62 to 21.5 ms with incremental delta of 1.8 ms, TR = 30 ms, FA = 20°, BW = 1953 Hz/pixel, pixel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) to further estimate whole-brain T2*R map. T2*R maps were reconstructed using the magnitude images only and considering a monoexponential decay. We also acquired 2D high-resolution blocks (10 slices) of T2*-weighted images (TE = 27.2 ms, TR = 517 ms, FA = 25°, BW = 30 Hz/pixel, pixel size = 0.25 × 0.25 × 1 mm3). Total scan time per subject was about 1 h on the 7 T scanner. The 3 T protocol consisted of a single standard 3D T1 MPRAGE sequence (TE = 2.98 ms, TR = 2300 ms, TI = 900 ms, FA = 9°, BW = 238 Hz/pixel, pixel size = 1 × 1 × 1.1 mm3). Given the duration of the MRI evaluation at 7 T, FLAIR and T2* sequences were not part of the acquisition protocol, as all patients also had within six months for their usual follow-up in our referral center both FLAIR (TR/TE/TI 8402/161/2002 ms, pixel size = 0.94 × 0.94 × 5.5 mm3) and T2*-weighted gradient echo (TR/TE 500/15 ms, pixel size = 0.98 × 0.98 × 5.5 mm3) acquisition on a 1.5 T scanner (Signa General Electric Medical Systems).19

Image processing

Lesion quantification

Delineation of WMH and of lacunes was performed according to the STRIVE criteria.20 Masks of WMH and of lacunes were obtained for each patient from the FLAIR sequence and the 3D-T1 sequence, respectively. Volumes of WMH and of lacunes were obtained by multiplying the number of voxels of the masks by voxel size. The volume of whole brain parenchyma was obtained from the 3D-T1 sequence using Brainvisa (http://brainvisa.info).21 To take into account differences in head size among subjects, the brain parenchymal fraction was used in analyses.22 The number of microbleeds was recorded for all patients manually from the T2*-weighted sequences. All these parameters were obtained with methodologies that have been previously validated in CADASIL.7,19,23

Relaxation times of specific and nonspecific WMH

The whole white matter volumes were extracted from the 3D-T1 sequence using BrainVisa, with systematic corrections in each patient to take into account T1 signal abnormalities possibly corresponding to white matter lesions by using the corresponding mask of WMH.19 To do so, the WMH mask from the FLAIR sequence was registered to the 3D-T1 sequence using the rigid registration algorithm of FSL (FLIRT, http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FLIRT),24 as previously reported and validated.7 Voxels corresponding to white matter but erroneously attributed to gray matter by the segmentation process were reincluded in the whole white matter mask. Then, masks of the whole white matter and of WMH were registered to the acquisition space of relaxometry maps.

We defined a specific region of interest (ROI) corresponding to the white matter of anterior temporal poles and superior frontal gyri defined using the structural labels of the digitized version of the Talairach atlas registered into the Montreal Neurological Institute template25 (see supplementary material). We chose not to include in analyses the white matter of external capsules, given their particular shape and small size in relation to possible registration inaccuracies, precluding accurate comparisons between individuals with different brain morphologies. Additionally, we defined a nonspecific ROI corresponding to the remaining white matter. For each patient, specific (or nonspecific) WMH were defined as WMH voxels inside the specific (or nonspecific) ROI.

In patients, mean T1R and T2*R of specific and nonspecific WMH were calculated by averaging values of T1R and T2*R of specific (resp. nonspecific) WMH voxels. In controls, who had virtually no WMH, mean T1R and T2*R were calculated by averaging the values of T1R and T2*R of all voxels within specific and nonspecific ROI.

Voxel-wise group analysis of T1R and T2*R within WMH

For each patient, T1R and T2*R maps as well as masks of WMH were registered to the MNI template using the nonrigid registration algorithm of FSL (FNIRT, http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FNIRT).26 Group-level maps of T1R and T2*R within WMH were determined by averaging for each voxel of the MNI template, after spatial smoothing, the T1R (respectively the T2*R) of patients having WMH at this particular location. Long relaxation times were defined by values superior to two standard deviations above the mean of the patient’s group across all WMH voxels. Clusters with long T1R or long T2*R with significant sizes (above 500 mm3) were extracted and meshed in 3D.

High-resolution 7T structural MRI

Relaxometry maps and 7 T high-resolution structural T2*-weighted scans (0.25 × 0.25 × 1 mm3) were registered manually (Mango software, Research Imaging Center, UTHSCSA, http://ric.uthscsa.edu/mango) given their different contrast, resolution, and coverage. High-resolution images were systematically screened visually to detect macroscopic differences between specific and nonspecific WMH, taking into account normal variations of brain structure in controls. Additionally, given the known high number of dilated perivascular spaces (dPVS) at the cortico-subcortical junction in CADASIL,27 which could lengthen T1R and T2*R of the white matter by including CSF signal, we rated visually the density of dPVS for each high-resolution block as follows: grade 0 in the absence of dPVS, grade 1 for very few dPVS (<5), grade 2 for few dPVS (≥5 and <15), grade 3 for multiple dPVS (≥15). For patients, the density was evaluated: (1) in specific WMH, (2) at the border of specific WMH, (3) in nonspecific WMH, and (4) at the border of nonspecific WMH. For controls, the density was evaluated: (1) in specific ROI and (2) in nonspecific ROI.

Results

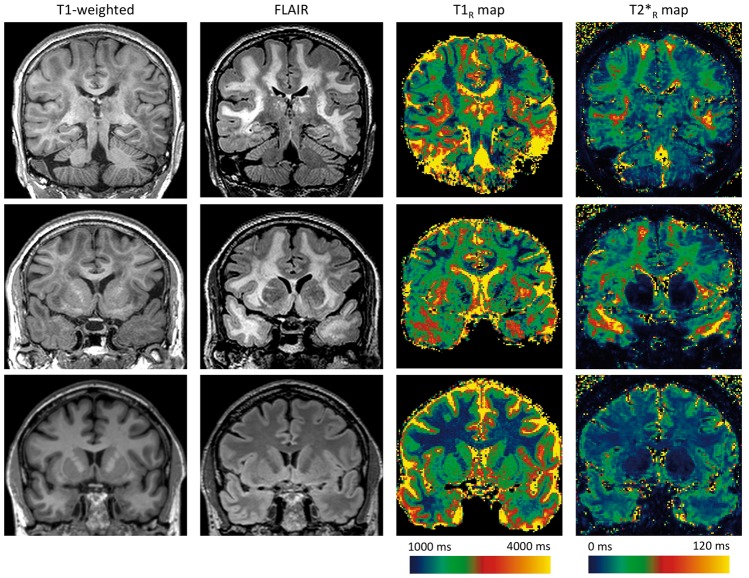

Patients and healthy controls did not differ in age or sex. Both groups performed similarly at the MMSE. Regarding MRI markers, brain parenchymal fraction did not significantly differ between groups (see Table 1 for details). As expected, we observed a strong lengthening of T1R and of T2*R within WMH, with important regional variations, as illustrated by a typical case (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of CADASIL patients and healthy controls.

| CADASIL patients (n = 20) | Healthy controls (n = 17) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender (n, %) | 9/20 (45%) | 6/17 (35%) | 0.79 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD, range | 56.7 ± 11.1, 35.5–77.1 | 57.2 ± 12.3, 33.2–74.7 | 0.91 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD, range | 28.4 ± 1.8, 24–30 | 28.9 ± 1.2, 26–30 | 0.44a |

| Brain parenchymal fraction, mean ± SD, range | 0.85 ± 0.04, 0.78–0.90 | 0.84 ± 0.04, 0.74–0.89 | 0.26a |

| WMH volume, mean, median, range (cm3) | 174, 110, 11–510 | No significant lesions | – |

| Volume of lacune, mean, median, range (cm3) (n = 9/20, 45%)b | 0.53, 0.34, 0.01–1.36 | 0 | – |

| Number of microhemorrhages, mean, median, range (n = 5/20, 25%)b | 9, 5, 1–32 | 0 | – |

CADASIL: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; WMH: white matter hyperintensities.

Adjusted for age and sex

In patients with such lesions (number given in parentheses).

Figure 1.

Spatial heterogeneity of T1R and T2*R within white matter hyperintensities. Three tesla coronal slices of 3D T1-weighted, 3D FLAIR images and 7 T reconstructed T1R and T2*R maps of a 65-year CADASIL patient with extensive white matter hyperintensities (WMH) (first and second lines) and of a 60-year control (third line). (The 3D FLAIR has been acquired during an ongoing MRI protocol and is used here solely for illustration purpose.) T1-weighted and FLAIR images show WMH both in deep white matter and in specific regions such as temporal poles, external capsules, and superior frontal areas. Relaxometry maps illustrate that WMH with the longest relaxation times are located in anterior temporal, subinsular, and superior frontal areas. From deep white matter to these areas, we can observe an increase in T2*R within WMH from 30 ms to more than 120 ms. By comparison, T2*R is much shorter and homogeneous in the white matter of the control (around 25 ms).

CADASIL: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy; FLAIR: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Comparison of relaxation times in specific and nonspecific WMH

ROI analysis

In patients, both T1R and T2*R were significantly longer in specific WMH than in nonspecific WMH with a relative difference of 7 and 12%, respectively (see Table 2). In controls, T1R was also significantly longer in specific ROI compared to nonspecific ROI but the difference was 2.5 times smaller than in patients (3%), while the difference in T2*R between specific and nonspecific ROI was minimal (0.2%).

Table 2.

Differences in relaxation times between specific and nonspecific white matter hyperintensities in patients and specific and nonspecific regions of interest in controls.

| Relaxation times (ms) | Specific WMH | Nonspecific WMH | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N = 20) | |||

| T1R, mean ± SD | 2309.0 ± 120.1 | 2144.7 ± 138.2 | <0.001 |

| T2*R, mean ± SD | 39.7 ± 4.8 | 35.3 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Specific ROI | Nonspecific ROI | ||

| Controls (N = 17) | |||

| T1R, mean ± SD | 2108.8 ± 42.0 | 2039.2 ± 35.6 | <0.001 |

| T2*R, mean ± SD | 24.5 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 1.0 | 0.71 |

ROI: region of interest; WMH: white matter hyperintensities.

Paired t-test.

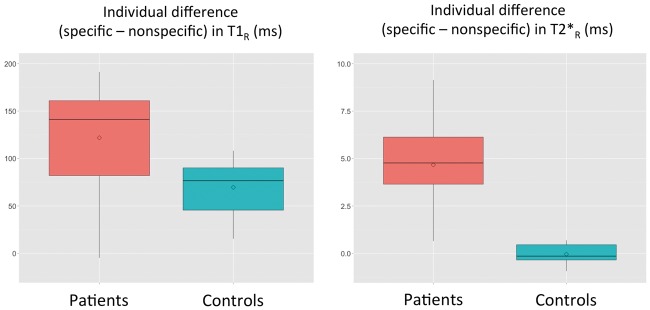

The boxplots in Figure 2 represent the mean difference in T1R and T2*R between specific and nonspecific WMH in each patient and between specific and nonspecific ROI in each control. When assessed by multiple linear regressions, the relative difference in T1R or in T2*R between specific and nonspecific WMH was neither associated with age nor with the volume of WMH (detailed results of the regression models are provided in supplementary material).

Figure 2.

Boxplots illustrating the mean differences in T1R and T2*R between specific and nonspecific white matter hyperintensities calculated for each CADASIL patient and between corresponding ROI containing normal appearing white matter calculated for each control. Differences in T1R and T2*R were computed for each patient between voxels corresponding to specific and nonspecific white matter hyperintensities (WMH). Differences in T1R and T2*R were computed for each control between voxels of the specific ROI and voxels of the nonspecific ROI containing normal appearing white matter. The boxplots represent mean values and spread at the group level of these differences. Please note that T1R and T2*R are represented using different scales.

CADASIL: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy; ROI: region of interest.

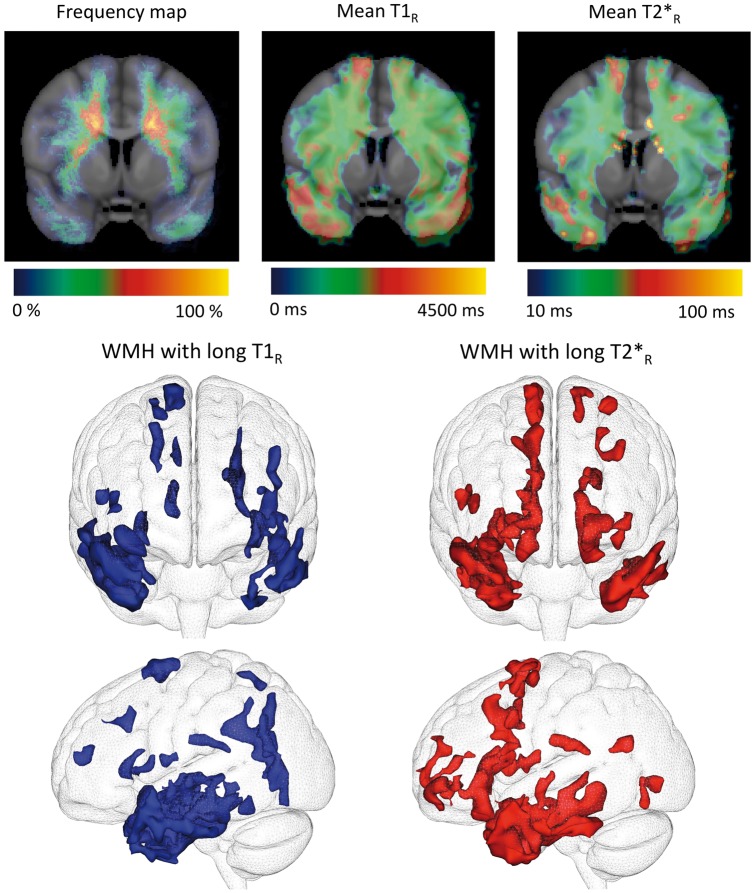

Unbiased voxel-wise analysis

Both averaged maps of T1R and of T2*R within whole WMH revealed that the longest relaxation times were observed symmetrically within the anterior temporal areas, the external capsules, and the superior frontal gyri in patients (Figure 3). This pattern of WMH voxels with very long T1R or very long T2*R appeared strikingly similar to that of the specific WMH. Whether the slight differences observed mainly in the superior frontal gyri between T1R and T2*R patterns reflect differences in tissue composition or is related to technical aspects remains unknown. By contrast, nonspecific WMH were characterized by shorter relaxation times.

Figure 3.

Group analysis of spatial heterogeneity of T1R and T2*R within white matter hyperintensities. Top (from left to right): Frequency map (for each voxel, proportion of patients presenting with white matter hyperintensities (WMH) for this given voxel), T1R map and T2*R map in MNI template across the CADASIL group (N = 20) showing WMH with long relaxation times in juxta-cortical areas (anterior temporal poles and superior frontal gyri). Bottom: Segmentation of WMH characterized by long T1R (left) or long T2*R (right) values (two standard deviations above the mean values calculated on all voxels of WMH in CADASIL patients). WMH in these fronto-temporal regions rigorously match specific WMH.

CADASIL: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy.

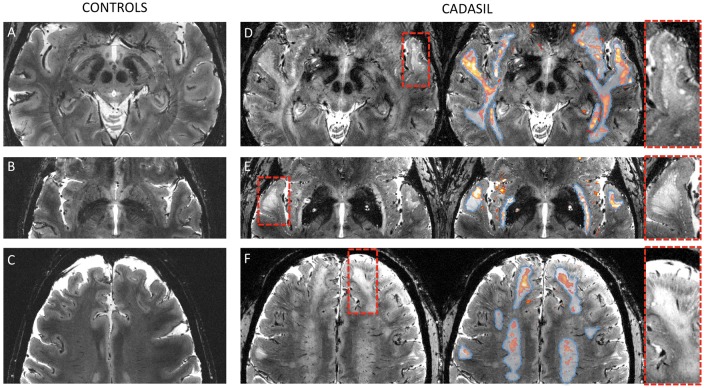

High-resolution 7 T structural MRI

High-resolution anatomical scans of high quality were obtained for 11/20 (55%) patients and 16/17 (94%) controls. Careful visual inspection by two experienced users of 7 T images in CADASIL (FDG and EJ) confirmed the presence of numerous dPVS at the cortico-subcortical junction in patients (see Figure 4). Table 3 reports the density of dPVS (grades 0, 1, 2, or 3) according to their location in both patients and controls. As expected, there was a significantly higher maximum density of dPVS across all regions in patients compared to controls (Mann–Whitney test: p < 0.001). In patients, there was no significant difference in dPVS density between specific and nonspecific WMH (paired Wilcoxon rank test: p = 0.34), but the grading was significantly higher at the border of specific WMH than in the three other regions (paired Wilcoxon rank test: p < 0.05) as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Ultra-high resolution MRI of specific white matter hyperintensities (WMH). Native 7 T ultra-high resolution (0.25 × 0.25 × 1 mm3) structural T2*-weighted images of two controls (a: 59 years; b and c: 60 years) and two CADASIL patients (d: 57 years, e and f: 61 years). In patients (right column), T2*R maps (1 × 1 × 1 mm3) were overlaid (red to yellow color) after registration and segmentation (T2*R > 50 ms) and whole white matter hyperintensities (WMH) obtained from conventional FLAIR sequences were delineated (dashed blue line). Red dashed boxes were zoomed in to show the unique aspect of the border between the cortical mantle and underlying white matter. Specific WMH are characterized by long T2*R in the close vicinity of which multiple dilated perivascular spaces were observed at the cortico-subcortical junction. Otherwise, no macroscopic visible abnormality was found in areas directly corresponding to long T2*R. In controls, T2*R was much shorter and there were few if any dilated perivascular spaces detectable.

CADASIL: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy; FLAIR: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.

Table 3.

Density of dilated perivascular spaces assessed from high-resolution images in patients and controls.

| Density of dPVS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 (%) | Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | |

| Patients | ||||

| Max across all regions | 0 | 0 | 55 | 45 |

| Specific WMH | 0 | 25 | 75 | 0 |

| Border of specific WMH | 0 | 0 | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| Nonspecific WMH | 0 | 55 | 45 | 0 |

| Border of nonspecific WMH | 0 | 18 | 73 | 9 |

| Controls | ||||

| Max across all regions | 0 | 69 | 25 | 6 |

| Specific ROI | 50 | 44 | 6 | 0 |

| Nonspecific ROI | 0 | 69 | 25 | 6 |

dPVS: dilated perivascular spaces; ROI: region of interest; WMH: white matter hyperintensities.

Except dPVS density, no visible difference was otherwise noted between patients and controls, nor between specific and nonspecific WMH in patients (see Figure 4 for specific WMH and supplementary Figure 2 for nonspecific WMH).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that specific and nonspecific WMH are characterized by different profiles of T1R and T2*R relaxation times that cannot only be explained by macroscopically visible differences on high-resolution images such as the number of dPVS nor by normal spatial variations of T1R and T2*R within the white matter. Importantly, the signal differences between specific and nonspecific WMH were observed both at the individual level (Figure 1) and at the group level (Figure 3) using two different methodologies (ROI-based and unbiased voxel-wise approaches). Altogether, these results strongly support that the microstructural alterations underlying WMH differ according to their location.

To note, T1R and T2*R lengthening have also been reported in the normal appearing white matter of CADASIL patients compared to controls using dedicated methods to compare similar anatomical regions.28,29 However, the amplitude of these differences was much lower compared to that observed between specific and nonspecific WMH in patients.

In the present study, the profile of T1R and T2*R, including the combination of very long T1R and T2*R is compatible with the presence of edema within specific WMH since the presence of water, wherever localized at the histological level, dramatically lengthens relaxation times. Our results are in line with the early appearance of intramyelinic edema reported in CADASIL mice.30 To note, in a rat model of intramyelinic edema, the edema water volume fraction evaluated from histology was strongly correlated to the longest T2R component.31 Demyelination may also increase relaxation times but its effect is anticipated to be much more pronounced on T1R than on T2*R,32 which was not observed in our results.

In the present study, we showed that the lengthening of T1R and of T2*R within specific WMH could not be explained by the only presence of dPVS. Indeed, while the possible inclusion of dPVS in voxels of specific WMH might lengthen T1R and T2*R, very high-resolution scans showed that dPVS lied outside the specific WMH voxels with the longest T1R and T2*R. Besides, the close spatial relationships observed between dPVS and specific WMH (Figure 4) raises the question of common underlying mechanisms. Indeed, dPVS plays an important role in the drainage of interstitial fluid around the brain.33 As such, a local failure of fluid drainage from the white matter could be involved in this process, resulting in the enlargement of dPVS and the local accumulation of fluid as hypothesized in a neuropathological study of temporal poles in CADASIL.27

Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that our results are related to the chronological progression of WMH. Indeed, if WMH spread to subcortical areas in CADASIL because of the extension from deep to subcortical areas, specific WMH would likely appear later during the course of the disease. These WMH may originally have longer relaxation times and then evolve toward shorter relaxation times as nonspecific WMH. However, in this case, one would expect to detect an effect of age on the difference in relaxation time between specific and nonspecific WMH, which was not the case.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample sizes of patients and controls were small. However, patients were highly phenotyped and represent a homogeneous sample of patients at the early clinical stage of the disease. Also, relaxometry necessitates several acquisitions with different parameters, lengthening acquisition times, and requiring postprocessing. Besides, the interpretation of the results must be cautious as alterations of relaxometry cannot be controlled visually. This highlights the importance of results obtained in the control group as well as those from high-resolution images. Also, given the small number of patients and the very low variability of clinical expression, we could not explore the potential relationships between WMH subtypes and clinical severity or other MRI markers of SVD. Nonetheless, our results show that patients with a large extent of specific WMH have a lower volume of lacunes and a larger brain volume than other patients (supplementary Table 1). These preliminary results support the hypothesis that the mechanisms underlying specific WMH are distinct from those underlying nonspecific WMH and also suggest that specific WMH may have milder clinical consequences than nonspecific WMH.

Our study also has several strengths. First, we studied a small sample of patients at the early clinical stage of the disease with important variations in WMH extent, allowing testing the hypothesis of different substrates for specific and nonspecific WMH. We designed a unique ultra-high field MRI protocol combining relaxometry, which provides additional quantitative and reproducible values that help differentiating tissues that appear otherwise similar on conventional imaging, and high-resolution structural images to probe the tissue composition of WMH beyond classic approaches using conventional MRI.34 Finally, we observed coherent results with both unsupervised and ROI-driven analyses on two independent sources of data (T1R and T2*R maps) and verified that similar regional differences were not measured in a group of controls, thus supporting the fact that potential acquisition artifacts did not drive our results.

Conclusion

In summary, our results support the hypothesis that WMH in anterior temporal poles and superior frontal areas result from different mechanisms than WMH observed in other white matter areas. Notably, this difference that is likely related to strong variations in tissue water content may be a consequence of white matter edema. Further studies are needed to further explore the pathophysiology of the different types of WMH and whether specific and nonspecific WMH have distinct relationships with the clinical phenotype in CADASIL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Chantal Ginisty, Séverine Roger, and Séverine Desmidt (UNIACT, NeuroSpin) for performing the MRI acquisitions and preprocessing the data. They also acknowledge Jocelyne Ruffié, Véronique Joly-Testaud, and Laurence Laurier for the recruitment process of patients and controls and Lucie Hertz-Pannier for helpful discussion.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by grants from Fondation Avenir, CADASIL France association and Fondation Leducq (Transatlantic Network of Excellence on the Pathogenesis of Small Vessel Disease of the Brain, http://www.fondationleducq.org).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

FDG, HC, and EJ designed the study. FDG, AV, and EJ collected and analyzed the data. FDG and EJ wrote the initial draft of the paper. All the authors carefully revised the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at http://jcbfm.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0271678X17690164

References

- 1.Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Auer DP, Putz B, Gossl C, et al. Differential lesion patterns in CADASIL and sporadic subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy: MR imaging study with statistical parametric group comparison. Radiology 2001; 218: 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Sullivan M, Jarosz JM, Martin RJ, et al. MRI hyperintensities of the temporal lobe and external capsule in patients with CADASIL. Neurology 2001; 56: 628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013; 80: 844–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duering M, Csanadi E, Gesierich B, et al. Incident lacunes preferentially localize to the edge of white matter hyperintensities: insights into the pathophysiology of cerebral small vessel disease. Brain 2013; 136: 2717–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Ladis Study Group. 2001–2011: a decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) Study: what have we learned about white matter changes and small-vessel disease? Cerebrovasc Dis 2011; 32: 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Viswanathan A, Godin O, Jouvent E, et al. Impact of MRI markers in subcortical vascular dementia: a multi-modal analysis in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging 2010; 31: 1629–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabriat H, Herve D, Duering M, et al. Predictors of clinical worsening in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: prospective cohort study. Stroke 2016; 47: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jouvent E, Viswanathan A, Chabriat H. Cerebral atrophy in cerebrovascular disorders. J Neuroimaging 2010; 20: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao M, Jouvent E, During M, et al. Extensive white matter hyperintensities may increase brain volume in cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke 2012; 43: 3252–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Guio F, Mangin JF, Duering M, et al. White matter edema at the early stage of cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke 2015; 46: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011; 82: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazekas F, Kleinert R, Offenbacher H, et al. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology 1993; 43: 1683–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanathan A, Gray F, Bousser M-G, et al. Cortical neuronal apoptosis in CADASIL. Stroke 2006; 37: 2690–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Guio F, Reyes S, Vignaud A, et al. In vivo high-resolution 7 Tesla MRI shows early and diffuse cortical alterations in CADASIL. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jouvent E, Reyes S, De Guio F, et al. Reaction time is a marker of early cognitive and behavioral alterations in pure cerebral small vessel disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2015; 47: 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng HL, Wright GA. Rapid high-resolution T(1) mapping by variable flip angles: accurate and precise measurements in the presence of radiofrequency field inhomogeneity. Magn Reson Med 2006; 55: 566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarnykh VL. Actual flip-angle imaging in the pulsed steady state: a method for rapid three-dimensional mapping of the transmitted radiofrequency field. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouvent E, Mangin J-F, Porcher R, et al. Cortical changes in cerebral small vessel diseases: a 3D MRI study of cortical morphology in CADASIL. Brain 2008; 131: 2201–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangin J-F, Rivière D, Cachia A, et al. A framework to study the cortical folding patterns. NeuroImage 2004; 23: S129–S138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jouvent E, Viswanathan A, Mangin JF, et al. Brain atrophy is related to lacunar lesions and tissue microstructural changes in CADASIL. Stroke 2007; 38: 1786–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouvent E, Mangin JF, Duchesnay E, et al. Longitudinal changes of cortical morphology in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 1002 e29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, et al. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 2002; 17: 825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, et al. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp 2000; 10: 120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, et al. FSL. NeuroImage 2012; 62: 782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto Y, Ihara M, Tham C, et al. Neuropathological correlates of temporal pole white matter hyperintensities in CADASIL. Stroke 2009; 40: 2004–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Guio F, Reyes S, Duering M, et al. Decreased T1 contrast between gray matter and normal-appearing white matter in CADASIL. AJNR 2014; 35: 72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Guio F, Vignaud A, Ropele S, et al. Loss of venous integrity in cerebral small vessel disease: a 7-T MRI study in cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Stroke 2014; 45: 2124–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cognat E, Cleophax S, Domenga-Denier V, et al. Early white matter changes in CADASIL: evidence of segmental intramyelinic oedema in a pre-clinical mouse model. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014; 2: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harkins KD, Valentine WM, Gochberg DF, et al. In-vivo multi-exponential T2, magnetization transfer and quantitative histology in a rat model of intramyelinic edema. NeuroImage Clin 2013; 2: 810–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stuber C, Morawski M, Schafer A, et al. Myelin and iron concentration in the human brain: a quantitative study of MRI contrast. NeuroImage 2014; 93: 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weller RO, Hawkes CA, Kalaria RN, et al. White matter changes in dementia: role of impaired drainage of interstitial fluid. Brain Pathol 2015; 25: 63–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Guio F, Jouvent E, Biessels GJ, et al. Reproducibility and variability of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging markers in cerebral small vessel disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1319–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.