Abstract

Introduction

Hepatitis B and C represent an important co-infection for people living with HIV worldwide. Nepal wants to be part of the international mobilization for viral hepatitis elimination, and has pursued better understanding of the epidemic in its territory through scientific research.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of seroprevalence studies hepatitis B and C in Nepal following the PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram.

Results

Fifty-four scientific publications and reports were selected for this review. Nearly a quarter of these documents have been issued in recent years and many are authored by non-governmental organizations in Nepal. The collective of information displays a wide range of alarming prevalence rates, particularly for girls and women survivors of human trafficking and a progressive participation of civil society in viral hepatitis epidemiology research in the country.

Conclusion

This paper presents a most complete review of hepatitis B and C and HIV co-infection prevalence studies in different population groups from 1973 to 2016. A comprehensive analysis of the epidemiology and apparent trends in public health research and policy making in Nepal are also addressed in this document. We expect this to be a most important tool for improvements in future interventions for both epidemics in the country.

Keywords: Viral hepatitis, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Systematic review, Epidemiology, Nepal

Background

Viral hepatitis has become a leading cause of death and disability worldwide - estimated to be responsible for over 1.4 million deaths every year. Chronic viral hepatitis, mostly represented by the hepatitis B and C viruses infections (HBV and HCV, respectively), is a major cause of increasing events of high morbidity and mortality such as cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Both viruses are more easily transmissible than HIV [1].

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) establishes the year of 2030 as a desirable deadline for the end of many epidemics, including viral hepatitis. Nepal, a landlocked central Himalayan country in South Asia, has committed to the seventeen ambitious goals of SDG, and pursues to graduate from the least developed country rank by 2022. Nepal already presented remarkable achievements in infectious diseases, particularly the HIV response [2–4]. However, the understanding of viral hepatitis impacts to the country is limited. There is no national plan devised for the elimination of viral hepatitis and hepatitis C has only been briefly mentioned in the National HIV Strategic Plan 2016–2021 (Nepal HIVision 2020) [5].

Multiple community- and facility-based seroepidemiological surveys for viral hepatitis and co-infections have taken place in Nepal since 1973 [6–8]. Studies have assessed different population groups mostly in urban areas of Kathmandu Valley and to a lesser extent in other development regions.

As new National Guidelines for Viral Hepatitis are being developed, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS in Nepal (UNAIDS Nepal) understands this comprehensive review is a most welcome tool for future research. We expect this document to be useful for mathematical models, advocacy for key populations, improvements in public health policy, and setting priorities for successful elimination of hepatitis B and C.

Methods

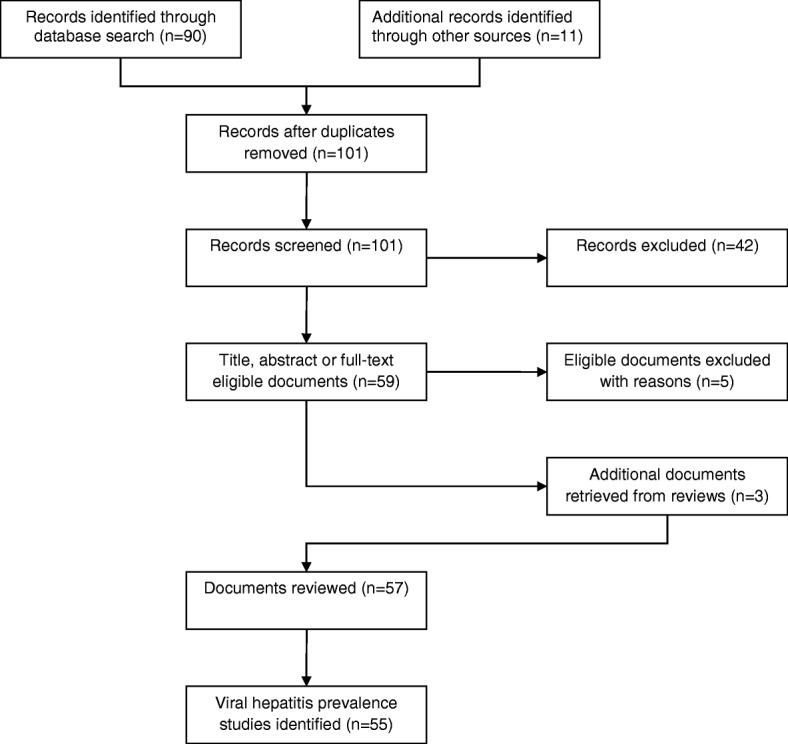

We conducted a systematic review of seroprevalence studies of hepatitis B and C following the PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram [9]. Our main sources of data for this research were: 1) PubMed (Medline), through the following search expression “((“Hepatitis B”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis B, Chronic”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis B virus”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis B Surface Antigens”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis B Antibodies”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis B”[Text] OR “Hepatitis C”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis C, Chronic”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis C Antibodies”[Mesh] OR “Hepatitis C”[Text]) AND (“Nepal”[Mesh] OR “Nepal”[Text]))”; 2) reports provided by the Government of Nepal (GoN); 3) reports authored by international agencies and non-governamental organizations (NGOs); and 4) personal correspondence to authors.

Study selection

Two researchers took part in all steps of the reviewing process. We assessed our initial search results for eligibility through title, abstract and full-text analysis. Duplicates were not identified, but two publications were found to be supplemental to previously evaluated studies. One review obtained during the search presented additional data for three studies unavailable in digital media. Personal correspondences were sent to authors to obtain additional information. We could not identify any repetition of datasets.

Publications were considered eligible for inclusion if they presented own and original data (absolute numbers or percentage) for any population group, Nepalese or residing in Nepal, at any given site and time for at least one of the following outcomes of interest: 1) hepatitis B seroprevalence, active infection or exposure; and 2) hepatitis C seroprevalence as detected by anti-HCV tests.

Selected publications were excluded if full-text material could not be retrieved, if published before 1981 and if abstract could not provide sufficient information for any of the three outcomes of interest.

Data extraction

The following data were then extracted from each eligible study included in this review: year of publication, population group, site, month and/or year of data collection, sample size, numbers/percentage of positive results for hepatitis B, C, HIV and syphilis; and authors’ name.

Seven studies did not provide details of which tests were used to define active HBV infection [7, 10–15]. One study identified did not provide details about which tests were used to define seroprevalence of exposition to HBV [16].

We chose to display results for every study total population and for as many subgroups as possible. Figures were obtained through full-text analysis and personal correspondence with authors. All numbers were thoroughly revised.

Results

This review selection process is depicted in Fig. 1, as adapted from the PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram [9]. Initial search expression resulted in ninety different records with no duplicates. Forty-two citations were excluded after title, abstract and full-text screening and one citation was found to be supplemental. One report from Asian Network of People Who Use Drugs (ANPUD), one from HEPA Foundation/United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), one from United Nations Development Program (UNPD), two from Nepal Red Cross Society (NRCS) and six from Ministry of Health of Nepal (MoH), including the Global AIDS Response Progress Report 2015 (GARRP), were added to the group of forty-eight eligible citations, resulting in fifty-nine documents.

Fig. 1.

Flow of article selection for the viral hepatitis B and C prevalence studies in Nepal

Five records were excluded because full-text could not be retrieved and their abstracts did not have data on any of the three outcomes of interest. Three additional documents from 1987 to 1990, which were not listed in PubMed, were identified from a review and later included in the collective. Fifty-seven documents relevant to fifty-five relevant prevalence studies were selected for this review.

Table 1 presents the collective of viral hepatitis prevalence studies with stratified population groups according to WHO key terms.

Table 1.

Studies reporting hepatitis B and C in Nepal

| SN | YEAR | POPULATION, SITE, TIME | SAMPLE SIZE, N | ANTI-HIV(%) | HBV | ANTI-HCV | NOTES | AUTHOR(S) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBSAG(%) | ANTI-HBC(%) | ANTI-HBS(%) | ||||||||

| 1 | 1973 | Patients attending hospitals in Kathmandu during infectious hepatitis outbreak, January 1973 to October 1973 | 53 sera samples | – | 0 (0.00) | – | – | – | – | Hillis A et al. [6] |

| 2 | 1984 | Hospitalized patients with jaundice referred to Shree Tribhubn Chandra Military Hospital, Kathmandu and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, 1981 to 1982 | 41 patients | – | 6 (7.50) | – | – | – | – | Kane MA et al. [28] |

| Outpatients referred to Shree Tribhubn Chandra Military Hospital, Kathmandu and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, 1981 to 1982 | 39 patients | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| 3 | 1987 | Children age 0–10 years, Surkhet Valley | 45 childrena | – | (6.6) | – | (22.2) | – | – | Shreshta SM. [72] |

| Children, teenagers and adults age 11–20 years, Surkhet Valley | 65 children, teenager and adultsa | – | (3.0) | – | (46.6) | – | – | |||

| Adults age 21–40 years, Surkhet Valley | 82 adultsa | – | (9.7) | – | (44.0) | – | – | |||

| Adults 41+ years, Surkhet Valley | 33 adultsa | – | (6.0) | – | (25.0) | – | – | |||

| Girls and women, 0–41+ years, Surkhet Valley | – | – | (9.8) | – | – | – | ||||

| Boys and men, 0–41+ years, Surkhet Valley | – | – | (4.4) | – | – | – | – | |||

| General population age 0–41+, Surkhet Valley | 225 peoplea | – | (6.6) | – | (35.0) | – | – | |||

| 4 | 1987 | Tibetan children age 0–9 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 34 children | – | (20.0) | (32.0)a | – | – | – | Shrestha SM. [30] |

| Tibetan children, teenagers and adults age 10–19 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 79 children, teenagers and adults | – | (10.0) | (39.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Tibetan adults age 20–29 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 106 adults | – | (18.0) | (55.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Tibetan adults age 30–39 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 61 adults | – | (20.0) | (46.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Tibetans age 40–49 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 95 adults | – | (15.0) | (36.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Tibetans age 0–49 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 375 people | – | (16.0) | (45.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese children age 0–9 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 113 children | – | (0.0) | (3.5)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese children, teenagers and adults age 10–19 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 198 children, teenagers and adults | – | (0.5) | (5.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese adults age 20–29 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 110 adults | – | (1.8) | (5.4)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese adults age 30–39 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 49 adults | – | (0.0) | (32.6)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese adults age 40–49 years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 25 adults | – | (0.0) | (16.0)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese adults age 50+ years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 45 adults | – | (2.2) | (7.8)a | – | – | – | |||

| Nepalese age 11–41+ years, Hemza, Tashi Ling, Pokhara; Jawalkhel, Kathmandu Valley | 540 people | – | (0.7) | (36.0)a | – | |||||

| 5 | 1988 | Patients during 1983 enterically transmitted non A–non B hepatitis outbreak, Kathmandu Valley | 150 patients | – | 34 (13.60)a | – | – | Nuti M [10] | ||

| Controls during 1983 non A–non B hepatitis outbreak, Kathmandu Valley | 100 people | – | – | – | ||||||

| 6 | 1988 | Lactating women from six villages of Kathmandu Valley | 26 women | – | 0 (0.00) | 4 (15.38) | 8 (30.77) | – | – | Reynolds RD et al. [73] |

| Breastfed infants age 2–6 months from six villages of Kathmandu Valley | 26 infants | – | – | – | – | |||||

| 7 | 1989 | Patients age 20–40 years attending four Kathmandu hospitals, Kathmandu, 1985 | 460 sera samples | 0 (0.00) | 5 (1.09) | 64 (13.91) | – | – | – | Mertens T et al. [74] |

| 8 | 1990 | Children age 0–5 years | 57 healthy children | – | 0 (0.00) | – | 5 (8.77) | – | – | Shrestha SM [75] |

| Children and teenagers age 6–15 years | 359 healthy children ad teenagers | – | 8 (2.23) | – | 15 (4.18) | – | – | |||

| Teenagers and adults age 16–41 years | 1788 healthy teenagers and adults | – | 16 (0.89) | – | 158 (8.84) | – | – | |||

| Adults, 41+ years | 351 healthy adults | – | 2 (0.57) | – | 35 (9.97) | – | – | |||

| Girls and women, 0–41+ years | 1529 healthy women | – | 9 (0.59) | – | 76 (7.40) | – | – | |||

| Boys and men, 0–41+ years | 1026 healthy men | – | 17 (1.65) | – | 138 (9.02) | – | – | |||

| General population, 0–41+ years | 2555 healthy individuals | – | 26 (1.02) | 23 (0.90) | 214 (8.4) | – | – | |||

| 9 | 1991 | Spouses of HBsAg chronic carriers | 34 people | – | 6 (17.65) | – | 15 (44.12) | – | – | Shrestha SM et al. [29] |

| Offspring of HBsAg chronic carriers | 73 people | – | 15 (20.55) | – | 17 (23.29) | – | – | |||

| Siblings of HBsAg chronic carriers | 29 people | – | 9 (31.03) | – | 11 (37.93) | – | – | |||

| 10 | 1993 | Children age 0–4 years, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 177 children | – | 64 (19.28) | 161 (17.05) | 213 (22.56) | – | – | Goh et al. [32] |

| Children age 5–14 years, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 155 children | – | – | – | ||||||

| Children and adults age 15–24 years, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 227 children and adults | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Adults age 25–34 years, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 289 people | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Adults 35+ years, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 96 people | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Gurkha Community members, Gurkha Contingent, Singapore | 944 people | – | 26 (2.75) | – | – | |||||

| 11 | 1994 | Patients with chronic hepatitis attending Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 20 patients | – | 12 (60.00) | – | – | 5 (25.00) | – | Shreshta SM et al. [26] |

| Patients with cirrhosis attending Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 63 patients | – | 25 (39.68) | – | – | 9 (14.28) | – | |||

| Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma attending Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 62 patients | – | 20 (29.41) | – | – | 6 (9.68) | – | |||

| Patients with chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma attending Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 145 patients | – | 57 (39.31) | – | – | 20 (13.79) | – | |||

| Pregnant women attending Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 83 women | – | 0 (0.00) | – | – | 3 (3.61) | – | |||

| Medical or paramedical personnel serving at Bir Hospital, Kathmandu | 296 people | – | 5 (1.69) | – | – | 10 (3.38) | – | |||

| 12 | 1994 | Female sex workers, Kathmandu Valley | 341 women | 3 (0.88) | 37 (10.85)a | – | Syphilis: 73 (21.41) | Bhatta P et al. [76] | ||

| 13 | 1994 | Villagers, Dharan, Sunsari; Pancha Kanya Village Development Committee, Ilam; Dhankuta Hile, Dhankuta; Basantapur Village Development Committee, Tehrathm | 303 serum samples | – | 0 (0.00) | – | 6 (1.98) | – | – | Rai SK et al. [77] |

| 14 | 1995 | Villagers, Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, 1987 | 676 blood samples | – | 2 (0.29) | 52 (7.69) | – | 1 (0.15) | – | Nakashima K et al. [78] |

| 15 | 1996 | People who inject drugs | 72 people | – | 4 (5.55) | 59 (81.94) | – | 58 (80.55) | – | Shrestha SM et al. [25] |

| 16 | 1997 | People who use drugs | 72 people | – | 2 (2.78) | 44 (61.11)b | 43 (59,72) | – | Shrestha SM et al. [16] | |

| People with chronic kidney disease | 41 people | – | 1 (2.44) | 6 (14.63)b | 1 (2.44) | – | ||||

| People with chronic liver disease | 145 people | – | 57 (39.31) | 74 (51.03)b | 12 (8.27) | – | ||||

| HBsAg carriers | 49 people | – | 49 (100.00) | 49 (100.00)b | 0 (0.00) | – | ||||

| Healthy individuals undergoing routine check-ups | 181 people | – | 9 (4.97) | 46 (25.41)b | 0 (0.00) | – | ||||

| 17 | 1998 | Patients age ≤ 15 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | 101 children and adults | – | – | 0/9 (0.00) | 1/9 (11.11) | 0/9 (0.00) | – | De Bruyn et al. [44] |

| Patients age 16–25 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | – | – | 0/34 (0.00) | 0/34 (0.00) | 4/34 (11.76) | – | ||||

| Patients age 26–35 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | – | – | 1/20 (5.00) | 0/21 (0.00) | 0/21 (0.00) | – | ||||

| Patients age 36–45 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | – | – | 2/14 (14.28) | 2/13 (15.38) | 0/13 (0.00) | – | ||||

| Patients age 46–55 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | – | – | 1/8 (12.50) | 1/8 (12.50) | 0/8 (0.00) | – | ||||

| Patients age ≥ 56 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital, Gorkha district, 1993 | – | – | 3/10 (30.00) | 4/10 (40.00) | 0/10 (0.00) | – | ||||

| 18 | 1999 | Male villagers age ≤ 24 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 44 boys and men | – | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.27) | – | 1 (2.27) | – | Sawayama Y et al. [40] |

| Female villagers age ≤ 24 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 43 girls and women | – | 1 (2.32) | 1 (2.32) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Villagers age ≤ 24 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 87 people | – | 1 (1.15) | 2 (2.30) | – | 1 (1.15) | – | |||

| Male villagers 25–34 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 40 men | – | 0 (0.00) | 2 (5.00) | – | 2 (5.00) | – | |||

| Female villagers 25–34 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 37 women | – | 1 (2.70) | 2 (5.40) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Villagers 25–34 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 77 people | – | 1 (1.30) | 4 (5.19) | – | 2 (2.60) | – | |||

| Male villagers 35–44 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 49 men | – | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.04) | – | 1 (2.04) | – | |||

| Female villagers 35–44 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 41 women | – | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.44) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Villagers 35–44 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 90 people | – | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.22) | – | 1 (1.11) | – | |||

| Male villagers 45–54 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 29 men | – | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.45) | – | 2 (6.90) | – | |||

| Female villagers 45–54 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 44 women | – | 0 (0.00) | 2 (4.54) | – | 1 (2.27) | – | |||

| Villagers 45–54 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 73 people | – | 0 (0.00) | 3 (4.11) | – | 3 (4.11) | – | |||

| Male villagers 55–64 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 29 men | – | 1 (3.45) | 5 (17.24) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Female villagers 55–64 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 39 women | – | 2 (5.13) | 6 (15.38) | – | 1 (2.56) | – | |||

| Villagers 55–64 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 68 people | – | 3 (4.41) | 11 (16.18) | – | 1 (1.47) | – | |||

| Male villagers ≥65 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 38 men | – | 0 (0.00) | 7 (18.42) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Female villagers ≥65 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 25 women | – | 0 (0.00) | 4 (16.00) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Villagers ≥65 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 63 people | – | 0 (0.00) | 11 (17.46) | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Female villagers age 15–90 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 229 women | – | 4 (1.75) | 16 (6.97) | – | 2 (0.87) | – | |||

| Male villagers age 15–90 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 229 men | – | 1 (0.44) | 17 (7.42) | – | 6 (2.62) | – | |||

| Villagers age 15–90 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages, August 1996 to September 1996 | 458 people | – | 5 (1.09) | 33 (7.20) | – | 8 (1.75) | – | |||

| 19 | 2000 | Healthy Nepalese Men from Eastern development region, October 1996 to March 1997 | 100 men | – | 2 (2.00) | – | – | – | – | Manandhar K et al. [79, 80] |

| Healthy Nepalese Men from Central development region, October 1996 to March 1997 | 100 men | – | 3 (3.00) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Healthy Nepalese Men from Western development region, October 1996 to March 1997 | 100 men | – | 4 (4.00) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Healthy Nepalese Men from Mid Western development region, October 1996 to March 1997 | 97 men | – | 4 (4.12) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Healthy Nepalese Men from Far Western development region, October 1996 to March 1997 | 81 men | – | 5 (6.17) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Healthy Nepalese Men from five different development regions, October 1996 to March 1997 | 478 men | – | 18 (3.76) | – | – | – | 17 < 40 yrs. old - | |||

| 20 | 2002 | Nepalese men age 16–50 years who required medical check-ups for employment abroad, July 1999 to September 1999 | 2585 men | – | 24 (0.93) | – | – | – | – | Bidya S [81] |

| 21 | 2003 | Boys and men < 19 years, Baba Medical Center, Kathmandu, September 2003 to June 2004 | 52 boys and men | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | – | – | – | – | Joshi SK et al. [34] |

| Men age 20–29 years, Baba Medical Center, Kathmandu, September 2003 to June 2004 | 375 men | 5 (1.33) | 9 (2.40) | – | – | – | Syphilis: 4/545 | |||

| Men age 30–39 years, Baba Medical Center, Kathmandu, September 2003 to June 2004 | 170 men | 5 (2.94) | 7 (4.11) | – | – | – | ||||

| Men age 40+ years, Baba Medical Center, Kathmandu, September 2003 to June 2004 | 30 men | – | 1 (3.33) | – | – | – | – | |||

| 22 | 2003 | People who inject drugs, Siddhi Polyclinic, Dillibazaar, Kathmandu | 400 people | – | – | – | – | 342 (85.5) | – | Shrestha IL [38] |

| Adults without history of injection drug use, Siddhi Polyclinic, Dillibazaar, Kathmandu | 400 people | – | – | – | – | 3 (0.75) | – | |||

| 23 | 2003 | Candidates for blood donation at Blood Bank Centre, NRCS, Teaching Hospital, Bhairahawa, February 2001 to April 2003 | 1548 samples | 2 (0.13) | 7 (0.45) | – | – | 2 (0.13) | – | Chander A et al. [18] |

| 24 | 2004 | Sherpa people age 15–66 years, Lukla, Solukhumbu district, 2004 | 103 people | – | 2 (1.94) | 25 (24.27) | 23 (22.33) | – | – | Chiba H et al. [82] |

| 25 | 2005 | Bhutanese refugees, Beldangi 2 Extension Camp, March 1998 to July 1998 | 467 people | – | 4 (0.86) | – | – | – | – | Shah BK et al. [83] |

| 26 | 2006 | Healthcare workers of Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, December 2001 to February 2002 | 145 people | – | 2 (1.38) | 21 (14.48) | – | – | – | Shrestha SK et al. [68] |

| 27 | 2006 | Male villagers, migrant-returnes from India and non-migrants, from five village development committees, Doti District, April 2001 | 149 people | 1 (0.67) | 16 (10.74) | – | – | – | – | Poudel K et al. [31] |

| 28 | 2007 | Patients with liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma attending Liver Foundation Nepal clinic, January 1998 to January 2004 | 121 patients | – | 48 (39.67) | 85 (70.25) | – | 15 (12.40) | – | Shrestha SM et al. [27] |

| Patients with liver cirrhosis attending Liver Foundation Nepal clinic, January 1998 to January 2004 | 70 patients | – | 20 (28.57) | 47 (67.14) | – | 6 (8.57) | – | |||

| Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma attending Liver Foundation Nepal clinic, January 1998 to January 2004 | 51 patients | – | 28 (54.90) | 38 (74.51) | – | 9 (17.65) | – | |||

| 29 | 2008 | Symptomatic people living with HIV/AIDS at Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, March 2004 to September 2005 | 54 patients | PLWH | 1 (1.85)a | 1 (1.85) | – | Dhungel BA et al. [11] | ||

| 30 | 2008 | Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2001 to 2002 | 72,459 blood samples | – | 627 (0.86) | – | – | 384 (0.52) | – | Karki S et al. [19] |

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2002 to 2003 | 73,758 blood samples | – | 911 (1.23) | – | – | 417 (0.56) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2003 to 2004 | 76,647 blood samples | – | 663 (0.86) | – | – | 321 (0.41) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2004 to 2005 | 82,677 blood samples | – | 644 (0.77) | – | – | 373 (0.45) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2005 to 2006 | 103,067 blood samples | – | 887 (0.86) | – | – | 366 (0.35) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2006 to 2007 | 115,720 blood samples | – | 430 (0.37) | – | – | 628 (0.54) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRSC, CBTS, hospital units/mobile camps all over Nepal, 2001 to 2007 | 524,328 blood samples | – | 4162 (0.82) | – | – | 2489 (0.47) | – | |||

| 31 | 2008 | Sex trafficked women and girls assisted by Maiti Nepal, Kathmandu | 246 women and girls | 74 (30.08) | 66/210 (31.43)a | – | Syphilis: 48% | Silverman J et al. [7] | ||

| 32 | 2009 | Candidates for blood donation at the Central Blood Transfusion Service, Nepal Red Cross Society (NRCS), Kathmandu, December 2006 to September 2007 | 33,255 individual samples | 65 (0.19) | – | – | – | Karki S et al. [12] | ||

| People living with HIV/AIDS diagnosed during blood donation at the Central Blood Transfusion Service, NRCS, Kathmandu, December 2006 to September 2007 | 65 individual samples tested positive for anti-HIV | PLWH | – | 7 (10.76) | – | |||||

| 33 | 2009 | Pregnant women admitted in the ward of NMCTH, Kathmandu, 2001 to 2007 | 5602 | – | 18 (0.32)a | – | – | Shreshta P et al. [84] | ||

| 34 | 2009 | People who inject drugs on Oral Substitution Therapy (OST), Kathmandu Valley, June 2009 | 118 people | – | – | – | – | 95 (80.50) | – | HEPA Foundation [85] |

| People who inject drugs, Kathmandu Valley, June 2009 | 82 people | – | – | – | – | 47 (57.32) | – | |||

| 35 | 2009 | Male candidates for blood donation, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 18,434 blood samples of male candidates | 25 (0.13) | 92 (0.50) | – | – | 128 (0.69) | Coinfection HIV/HCV: 8/128 | Shrestha AC et al. [20] |

| Female candidates for blood donation, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 3282 blood samples of female candidates | 2 (0.06) | 10 (0.30) | – | – | 11 (0.33) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation age ≤ 20 years, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 3310 blood samples | 2 (0.06) | 7 (0.21) | – | – | 7 (0.21) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation age 31–30 years, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 9818 blood samples | 12 (0.12) | 45 (0.45) | – | – | 75 (0.76) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation age 31–40 years, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 5763 blood samples | 10 (0.17) | 29 (0.50) | – | – | 42 (0.72) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation age 41–50 years, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 2433 blood sample | 3 (0.12) | 19 (0.78) | – | – | 13 (0.53) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation age 51–60 years, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 392 blood samples | 0 (0.00) | 3 (0.51) | – | – | 2 (0.51) | – | |||

| Candidates for blood donation, NRCS, Central Blood Transfusion Service (CBTS), Kathmandu, March 2008 to September 2008 | 21,716 blood samples | 27 (0.12) | 102 (0.46) | – | – | 139 (0.64) | – | |||

| 36 | 2010 | Candidates for blood donation in Banke blood transfusion service, July 2006 to June 2007 | 5211 | – | 63 (1.21)a | 6 (0.11) | – | Tiwari BR et al. [13] | ||

| Candidates for blood donation in Kaski blood transfusion service, July 2006 to June 2007 | 5995 | – | 21 (0.35)a | 10 (0.17) | – | |||||

| Candidates for blood donation in Morang blood transfusion service, July 2006 to June 2007 | 5351 | – | 47 (0.88)a | 14 (0.26) | – | |||||

| Candidates for blood donation in Banke, Kaski and Morang blood transfusion services, July 2006 to June 2007 | 16,557 | – | 131 (0.79)a | 32 (0.19) | – | |||||

| 37 | 2011 | People who inject drugs, age 18–40 years, 2011 | 40 people | – | – | – | – | 7 (17.50) | – | ANPUD. [86] |

| 38 | 2012 | Children age 10–12 years born from April 2000 to April 2002, before hepatitis B vaccine introduction, Kathmandu, April 2012 | 1200 children | – | 3 (0.25) | – | – | – | – | Upreti SR et al. [35] |

| Children age 5–6 years born from April 2006 to April 2007, after hepatitis B vaccine introduction, Kathmandu, April 2012 | 2187 children | – | 3 (0.14) | – | – | – | – | |||

| 39 | 2012 | Patients with ascites attending Nepal Medical College Hospital (NMCTH), Kathmandu, September 2011 to February 2012 | 43 patients | – | – | – | – | 2 (4.65) | – | Adhikari P et al. [87] |

| 40 | 2013 | People with one or more risk behaviors attending National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL), Kathmandu, November 2011 to May 2012 | 678 people | 105 (15.49) | – | – | – | – | – | Ojha CR et al. [88] |

| People living with HIV/AIDS diagnosed among study population, November 2011 to May 2012 | 105 people | PLWH | – | – | 14 (13.33) | – | – | |||

| 41 | 2014 | People living with HIV/AIDS attending B P Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS), Dharan; Society for Positive Atmosphere and Related Support to HIV and IDS (SPARSHA), Kathmandu; Sukhra Raj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, Kathmandu, April 2010 to March 2011 | 108 patients | PLWH | 4 (3.70)a | 3 (2.78) | HBV/HCV: 0 (0.00) | Barnawal SP et al. [15] | ||

| People who inject drugs living with HIV/AIDS attending BPKIHS, Dharan; SPARSHA, Kathmandu; Sukhra Raj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, Kathmandu, April 2010 to March 2011 | 205 patients | PLWH | 24 (11.71)a | 137 (66.83) | HBV/HCV: 10 (4.88) | |||||

| 42 | 2014 | Women living with HIV/AIDS, 18 years or older, February to March 2010 | 136 women | PLWH | – | – | – | 9 (6.61) | – | Poudel KC et al. [39] |

| Men living with HIV/AIDS, 18 years or older, February to March 2010 | 183 men | PLWH | – | – | – | 129 (70,49) | – | |||

| People who do not inject drugs living with HIV/AIDS, 18 years or older, February to March 2010 | 189 people | PLWH | – | – | – | 13 (6.88) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs living with HIV/AIDS, 18 years or older, February to March 2010 | 130 people | PLWH | – | – | – | 125 (95.15) | – | |||

| People living with HIV/AIDS, 18 years or older, February to March 2010 | 319 people | PLWH | – | – | – | 138 (43.26) | – | |||

| 43 | 2014 | Central Blood Transfusion Centre, 2012–2013 | 67,644 blood samples | 45 (0.07) | 150 (0.22) | – | – | 317 (0.47) | Syphilis: 394 (0.58) | NRCS [21] |

| Regional Blood Transfusion Centre, 2012–2013 | 47,733 blood samples | 40 (0.08) | 188 (0.39) | – | – | 126 (0.26) | Syphilis: 284 (0.59) | |||

| District/Emergency Blood Transfusion Centre, 2012–2013 | 61,624 blood samples | 35 (0.06) | 195 (0.32) | – | – | 121 (0.20) | Syphilis: 118 (0.19) | |||

| Hospital Blood Transfusion Unit, 2012–2013 | 12,320 blood samples | 3 (0.02) | 32 (0.26) | – | – | 21 (0.17) | Syphilis: 8 (0.06) | |||

| Total, 2012–2013 | 189,321 blood samples | 123 (0.06) | 565 (0.30) | – | – | 585 (0.31) | Syphilis: 804 (0.42) | |||

| 44 | 2014 | Children age 0–15 years with acute hepatitis attending the liver clinic of Bir Hospital and Norvic International Hospital of Kathmandu, Kathmandu, January 2006 to December 2010 | 312 children | – | 15 (4.81)a | – | – | Sudhamshu KC et al. [14] | ||

| 45 | 2015 | Women who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Nepalgunj | 3 women | 0 (0.00) | – | – | – | 0 (0.00) | – | Kinkel HT et al. [8] |

| Men who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Nepalgunj | 76 men | 6 (7.89) | – | – | – | 18 (23.68) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Nepalgunj | 79 people | 6 (7.59) | – | – | – | 18 (22.78) | – | |||

| Women who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services, Dharan; Biratnagar | 69 women | 9 (13.04) | 3 (4.35) | – | – | 17 (24.64) | – | |||

| Men who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services, Dharan; Biratnagar | 72 men | 12/70 (17.14) | 5 (6.94) | – | – | 50 (69.44) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services, Dharan; Biratnagar | 141 people | 21/139 (15.11) | 8 (5.67) | – | – | 67 (47.52) | – | |||

| Women who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan | 28 women | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.57) | – | – | 2 (7.14) | – | |||

| Men who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan | 153 men | 22/108 (20.37) | 2 (1.31) | – | – | 113 (73.86) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan | 181 people | 22/136 (16.18) | 3 (1.66) | – | – | 115 (63.53) | – | |||

| Women who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services, Nepalgunj; Dharan; Biratnagar; Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan, | 100 women | 9 (9.00) | 4 (4.00) | – | – | 19 (19.00) | – | |||

| Men who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Nepalgunj; Dharan; Biratnagar; Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan, | 301 men | 40/254 (15.75) | 10 (3.32) | – | – | 181 (60.13) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services submitted to HIV testing, Nepalgunj; Dharan; Biratnagar; Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan, | 354 people | 49 (13.84) | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| People who inject drugs attending Recovering Nepal services, Nepalgunj; Dharan; Biratnagar; Kathmandu; Lalitpur; Chitwan, | 401 people | 92/397 (23.17) | 14 (3.49) | 146 (43.89) | – | 200 (49.87) | – | |||

| 46 | 2015 | Patients attending Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, 2008 to 2013 | 25,708 individual blood samples | 218 (0.85) | – | – | – | – | – | Supram HS et al. [89] |

| People living with HIV/AIDS at Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, 2008 to 2013 | 218 individual blood samples | PLWH | 7 (3.21) | – | – | 9 (4.13) | – | |||

| 47 | 2015 | Boys and men 15+ years who inject drugs, Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa districts, July 2015 | 360 boys and men | 30 (8.33) | 3 (0.83) | – | – | 171 (47.50) | Syphilis: 4 (1.11); Syphilis History: 8 (2.22) | MoH/NCASC [90] |

| 48 | 2015 | Boys and men 16+ years who inject drugs, Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur districts, Kathmandu Valley, June 2015 to July 2015 | 340 boys and men | 22 (6.47) | 0 (0.00) | – | – | 75 (22.06) | Syphilis: 0 (0.00); Syphilis History: 0 (0.00) | MoH/NCASC [91] |

| 49 | 2015 | Boys and men 16+ years who inject drugs, Pokhara Valley, June 2015 to July 2015 | 345 boys and men | 10 (2.90) | 6 (1.74) | – | – | 45 (13.04) | -STI: 4 (1.16) | MoH/NCASC [92] |

| 50 | 2015 | People living with HIV/AIDS in Eastern Development Region, | 140 people | PLWH | 5 (3.57) | – | – | 67 (47.86) | – | UNDP/DFID/CMDN [2, 93] |

| People living with HIV/AIDS in Central Development Region, | 137 people | PLWH | 7 (5.11) | – | – | 30 (21.90) | – | |||

| People living with HIV/AIDS in West Development Region, | 203 people | PLWH | 13 (6.40) | – | – | 20 (9.85) | – | |||

| People living with HIV/AIDS in Midwest Development Region, | 51 people | PLWH | 0 (0.00) | – | – | 12 (23.53) | – | |||

| People living with HIV/AIDS in Far West Development Region, | 146 people | PLWH | 5 (3.42) | – | – | 3 (2.05) | – | |||

| People living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | 677 people | PLWH | 30 (4.43) | – | – | 132 (19.50) | – | |||

| People who inject drugs living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | 562 people | PLWH | 8 (1.42) | – | – | 91 (16.19) | – | |||

| Sex workers living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | – | PLWH | (0.1) | – | – | 0 (0.00) | – | |||

| Migrant workers living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | – | PLWH | (1.0) | – | – | (1.8) | – | |||

| Gay, Lesbian and Transgender people living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | – | PLWH | (0.4) | – | – | (0.4) | – | |||

| Non most at risk population living with HIV/AIDS in all Development Regions, | – | PLWH | (1.3) | – | – | (1.0) | – | |||

| 51 | 2016 | People who inject drugs with last 30-day frequent injection drug use attending rehabilitation centers, Kathmandu; Bhaktapur; Lalitupur; Sindupalchowk | 167 people | – | – | – | – | 20/87 (22.99) | – | Loewinger G et al. [94] |

| 52 | 2016 | Girls and women 16+ years who inject drugs, Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur districts, Kathmandu Valley, April 2016 to July 2016 | 160 girls and women | 14 (8.75) | 3 (1.87) | – | – | 34 (21.25) | 12 (7.50) | MoH/NCASC [95] |

| 53 | 2016 | Boys and men 15+ years who inject drugs, Rupandehi, Kapilvastu, Dang, Banke, Kailali and Kanchanpur districts | 300 boys and men | 7 (2.33) | 5 (1.67) | – | – | 24 (8.00) | Syphilis: 1 (0.33); Syphilis History: 5 (1.67) | MoH/NCASC [96] |

| 54 | 2016 | Patients who came in contact with HIV or other chronic liver disease and jaundice attending Teku Hospital, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, NRCS | 2700 patients | – | – | – | – | 100 (3.70) | – | Nepal A et al. [97] |

| 55 | 2016 | Central Blood Transfusion Centre, 2014–2015 | 69,303 blood samples | 21 (0.03) | 192 (0.28) | – | – | 224 (0.32) | Syphilis: 360 (0.52) | NRCS [22] |

| Regional Blood Transfusion Centre, 2014–2015 | 42,511 blood samples | 13 (0.03) | 151 (0.35) | – | – | 56 (0.23) | Syphilis: 115 (0.27) | |||

| District/Emergency Blood Transfusion Centre, 2014–2015 | 77,016 blood samples | 27 (0.03) | 227 (0.29) | – | – | 119 (0.15) | Syphilis: 260 (0.34) | |||

| Hospital Blood Transfusion unit, 2014–2015 | 28,324 blood samples | 7 (0.02) | 47 (0.16) | – | – | 23 (0.08) | Syphilis: 25 (0.09) | |||

| Total, 2014–2015 | 217,154 blood samples | 68 (0.03) | 617 (0.28) | – | – | 422 (0.19) | Syphilis: 760 (0.35) | |||

a: Study describes seroprevalence of active HBV infection. Test(s) used in the survey is(are) not specified

b: Study describes seroprevalence of exposure to HBV. Test(s) used in the survey is (are) not specified

Table 2 presents an analysis of the reviewed data and Cochran’s Q tests performed by Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. Estimated prevalence and heterogeneity has been presented for five population groups: PWID, populations at intermediate risk, populations at low risk (general population), populations with liver-related conditions and special clinical populations [17].

Table 2.

Findings of the meta-analyses for hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence measures

| Populations at risk | Studies | Samples | HCV prevalence estimates | Heterogeneity measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Total N | Mean (%) | 95% CI | Q (p-value)a | τ 2b | I2 (confidence limits-%)c | Prediction interval (%)d | |

| People who inject drugs | 15 | 3140 | 45.17 | 26.34–64.73 | 1714.1 (< 0.0001) | 0.1487 | 99.2 (99.0–99.3) | 0–100 |

| Populations at intermediate risk | 12 | 4998 | 12.76 | 5.44–22.47 | 668.83 (< 0.0001) | 0.0486 | 98.4 (97.9–98.7) | 0–59.58 |

| Populations at low risk (general population) | 28 | 972,123 | 0.68 | 0.54–0.86 | 683.44 (< 0.0001) | 0.2027 | 96.0 (95.1–96.8) | 0.26–1.75 |

| Populations with liver-related conditions | 6 | 411 | 11.51 | 7.73–15.87 | 7.40 (0.1926) | 0.0018 | 32.4 (0–72.7) | 3.48–22.89 |

| Special clinical populations | 3 | 133 | 1.67 | 0–5.81 | 2.79 (0.2473) | 0.0022 | 28.4 (0–92.6) | 0–75.38 |

aQ: the Cochran’s Q statistic is a measure assessing the existence of heterogeneity in HCV prevalence estimates

bτ2: the estimated between-study variance in the double arcsine transformed proportions of the true HCV prevalence estimates. The back-transformed τ2 was not calculated as the methodology to do so is not currently available

cI2: a measure assessing the magnitude of between-study variation that is due to differences in HCV prevalence estimates across studies rather than chance

dPrediction interval: estimates the 95% interval in which the true HCV prevalence in a new HCV study will lie

Population groups

Candidates for blood donation account for just seven prevalence studies and yet represent approximately 90 % of the population evaluated for viral hepatitis in Nepal since 1973. This overwhelming presence of candidates for blood donation in seroprevalence studies does not contribute to the understanding of populations at increased risk of HBV, HCV and HIV co-infection in Nepal as they rarely present seroprevalence rates higher than 1 % [12, 13, 18–22].

It is understood that people at increased risk of HBV, HCV and HIV co-infections should be properly represented in our review. We have succeeded to identify studies for most groups of interest: general population, children, adults, pregnant women, people who inject drugs (PWID), patients attending healthcare services, sexual and household contacts of people chronically infected by HBV, sex workers (SW), healthcare workers (HCW), migrant workers, refugees/displaced persons and survivors of human trafficking.

We found only one survey of viral hepatitis in lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender population (LGBT), including men who have sex with other men (MSM); and another in people with history of incarceration. All collected documents only referred to drug use as injection and did not acknowledge people who use drugs (PWUD) or different methods of drug administration (e.g. smoking heroin). [23, 24].

Hepatitis B

A disease preventable by vaccination, hepatitis B has been identified in our review in forty-six studies. HBsAg (surface antigen) positive tests had highest values in PWID (1.3–81.9%), [8, 25] patients with jaundice, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (7.5–60%); [16, 26–28] sexual and household contacts of people chronically infected by HBV (6.6–31), [29] girls and women survivors of sex trafficking (30%), [7] Tibetan population living in Kathmandu Valley (10–20%) [30] and Nepalese people outside Nepal (2.7–19.3) [31, 32]. On the other hand, the overall prevalence of hepatitis B in Nepal is estimated at 0.9%, [33].

Children, adults and general population cohorts also present interesting ranges for figures of hepatitis B seroprevalence. Older age groups present higher values for HBsAg [20, 34] and children born after vaccine implementation display reduced disease prevalence. [35].

Unfortunately, only one document presents viral hepatitis prevalence in LGBT population (MSM included), but it lacks important information on sample size and number of positive tests.

Exposure to hepatitis B virus, defined by anti-HBc (antibody against core antigen), has been assessed only in one key population - PWID, in two studies nearly twenty years apart. In 1996, more than 80 % of PWID had positive results for anti-HBc [25] and in 2015, when less than 45 % had positive results for the same marker [8].

Hepatitis C

One of the most important causes of morbidity [36] and mortality, particularly for people living with HIV (PLWH), [37] hepatitis C seroprevalence has been featured in thirty-one studies, in a total of approximately one million people in Nepal. Prevalence rates range from zero to more than 80%, with highest figures found in PWID (85.5 in males; 24.6 in females), [38] PLHIV (43.3) and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (17.6). [27, 38, 39].

Regardless of key population status, different prevalence rates have been observed in males and females [40]. Statistically significant differences according to gender can be verified in studies by Shrestha AC et al., between male and female candidates for blood donation in 2009 (0.69 vs. 0.33, respectively), [20] and Kinkel HT et a, between male and female PWID attending Recovering Nepal services in 2015 (19.00 vs. 60.13).

Age has been fundamental to the design of hepatitis C public health policies in many countries. It is known that age can relate to many factors in the epidemic: year of introduction of the virus, availability of tests and distribution of contaminated blood products, cumulative exposure (such as injection drug use, unprotected sexual activity across adult life), and status of harm reduction strategies [41–43]. In Nepal, age and hepatitis C have only been featured in two studies. De Bruyn et al. found anti-HCV to be positive in 11.8% of patients age 16–65 years attending Amp Pipal Hospital at Gorkha district in 1993; and Sawayama Y et al. found 2.27% in female villagers 45–54 years from Bhadrakali and Kotyang villages in 1996 [40, 44].

HIV co-infection prevalence

The first HIV prevalence study in Nepal dates 1989, [44] 1 year after the first case of HIV was detected in the country [45]. So far, eighteen prevalence studies also assessed at some time the HIV infection in their population, almost half a million people and roughly half of the population evaluated for HBV or HCV infection since 1985, the year of debut of anti-HIV ELISA tests.

As stated previously for overall population, candidates for blood donation represent the majority of the population tested for HIV co-infection in Nepal in the fifty-five viral hepatitis prevalence studies of this review. Yet, regardless of age and/or gender subgroups, candidates for blood donation have failed to present HIV seropositivity rates above 0.2% [20, 12, 18], constituting themselves a population of low prevalence for HIV co-infection. This data must not considered a proxy for general population, as candidates for blood donation have shown to be a “poor control group for non-genetic studies of diseases related to environmentally, behaviourally, or socially patterned exposures”, [46] but a reason to pursue further detection of viral hepatitis in priority populations.

As we evaluate the remaining studied population, we find that the highest rates of HIV infection found in this review do not belong to PWID, but sex trafficked girls and women, at an approximate 30% rate of infection in 2008 (74/246) [7). This is closely followed by PWID attending Recovering Nepal services, if accounted the participation of those with previously defined HIV status, with rates as high as 23.17% in 2015. Such findings are consonant with latest numbers of Family Health International data for HIV prevalence in PWID in Kathmandu (21% in 2009) [3] and increase of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in survivors of sex traffic, particularly for Nepalese girls and women [47–49].

Discussion

This review collects all available surveys performed in Nepal or with Nepalese population. It provides relevant information to policy makers, researchers and activists.

Developments of improved strategic information

It has been 44 years since the first viral hepatitis prevalence study took place in Nepal. Since then, sixty different publications, of which fifty-five are available in this review, have dedicated themselves to the better understanding of these epidemics.

Almost a quarter of these scientific publications and reports have been issued in the last 3 years. While there is still much to investigate, it is undeniable that Nepal’s civil society organizations and academia have been successful in their struggle to improve the reactive approach to viral hepatitis and HIV, shaping public health policy and visibility of key populations.

Superior strategic information and overall engagement to the epidemics lead to additional victories: the inclusion of LGBT issues in government policies, the return of harm reductions strategy in 2007, increase in donor funding for the response to HIV, and stronger ties between emerging and existing networks of key populations and representatives, healthcare professionals, academia, UNAIDS and GoN [50–55]. Such echoing common voice for change lead to the preliminary discussion of National Viral Hepatitis Guidelines and negotiation of licensed generic drugs for hepatitis C treatment at a fraction of prices offered to other developing countries [41, 56–59]. This recent collective represents a cornerstone for viral hepatitis in Nepal.

Gaps and key populations

It would seem to be that the shared modes of transmission of viral hepatitis and HIV, and the resulting similar epidemiological profiles, could translate into one equally successful public health intervention for both epidemics.

This is hardly the truth. Regardless of improvements in blood safety, availability of harm reduction services and assistance to sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections, with significant drops in HIV prevalence since the last decade, many key populations sustain subpar decrease in hepatitis C numbers. Such is the case of PWID in Nepal: hepatitis C exceeds three times the HIV prevalence in several cohorts.

Since 2000, PWID, PLHIV, sex workers and LGBT have figured in no less than seventeen different viral hepatitis prevalence studies, almost a third of studies collected in this review, contributing without precedents to the national strategic information and deeper understanding of the response to public health interventions. Additional publications also developed initial data for other population groups such as refugees/misplaced persons and survivors of sex traffic.

Our research could not retrieve any studies regarding transgender population, male sex workers or incarcerated persons in Nepal.

Hepatitis B vaccine coverage and elimination of vertical transmission (EVT)

Hepatitis B is a highly contagious, yet preventable disease [60, 61]. In recent years, many countries have chosen to scale up maternal and newborn care in order to secure a generation ‘free of hepatitis B’.

Our review provided two studies depicting hepatitis B in infancy in Nepal. The first study states hepatitis B is responsible for approximately 5 % of the cases of acute hepatitis in children 0–15 years [14]. The second study describes observed benefits of hepatitis B vaccine introduction to children in Nepal in 2002.

While no routine for hepatitis B immunoglobulin in prevention of vertical transmission has been implemented in Nepal, the rates of acute hepatitis related to HBV infection in children are quite different than the prevalence values of HBV in pregnant women (0.32%), an indicator that perhaps household exposure during infancy, and not mother-to-child transmission, is the reason for new but likely overlooked exposure during infancy (households).

Commercial vaccines for hepatitis B have been available worldwide since 1981 [62]. In Nepal, however, it has only been introduced in 2002. After fifteen years and despite recommendations issued by GoN, the country still struggles to provide appropriate vaccine coverage [35, 63].

Official government reports state that from 2002 until 2009, third-dose hepatitis B vaccine coverage for children 12–23 months stood at approximately 80%. [63, 64] World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimate improved coverage in 20,012 and 2013, slightly above 95%. [65] Such higher vaccine coverage numbers are not homogenous in Nepal - not all municipalities have immunization plans or appropriate structure at their disposal [63, 64]. Moreover, the intervention requires timely birth-dose vaccination for a most successful response, [66] and faces many other obstacles [67].

Hepatitis B vaccine is available to healthcare workers (HCW) in many countries. In Nepal, HCW are featured in two studies as an alternative to controls, with HBsAg seropositivity rates of 1.38 and 1.69% [26, 68]. These figures are lower than the ones presented by key populations, but still higher than those of candidates for blood donation. Further investigation reveals that HCW and students in Nepal have largely mishandled biosafety procedures while at high risk of exposure to the infective agent. Studies in tertiary care centers have shown frequent needle-stick and sharps-related injuries, and incomplete or fully ignored vaccination and post prophylaxis procedures [69–71].

Nevertheless, UNAIDS understands that the strengthening of the immunization plan and maternal health must be accompanied of a nationwide awareness campaign for HCW and future health professionals.

Community and the strengthening of health systems

Communities were the first responders to the HIV epidemic, nearly thirty years ago. They have continuously played an essential role in development of research, health services and shaping of public health policy worldwide, expanding their activities to sustainable and affordable vaccines and medicines for viral hepatitis.

Moreover, these collectives of advocates, researchers, clients or providers have the ability to work unisonous with marginalized populations, increasing the reach and quality of health systems and health services, often detecting overlooked issues such as stigma and discrimination. Whether leading research or promoting health services, civil society engagement improves awareness, prevention, diagnosis and retention in care. This has been the case of both viral hepatitis and HIV epidemic.

In Nepal, these initiatives are considered to be just as important as developments provided by academia, government and international agencies. It is clear that these endeavors provide a unique opportunity to fill critical gaps such as strategic information, low immunization coverage rates and elimination of mother-to-child and household transmission.

Conclusion

The present review illustrates different turning points in viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection epidemiology in Nepal. Since 1973, when the first study on viral hepatitis in the country was published, there have been many changes in the understanding of these epidemics.

These include the indirect effects of successful public health policies aimed towards HIV, such as the decrease of viral hepatitis prevalence in PWID, and their limitations, revealing overlooked population groups and issues in viral hepatitis that require public health policies of their own.

The review also allows one to witness the progressive scientific development by Nepalese researchers and institutions, and civil society representatives’ participation. Such collaboration correlates with increased number of studies and sample sizes in recent years including the survey of key populations, and will be fundamental for the success of the National HIV Strategic Plan 2016–2021 and achieving the SDG by 2030.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. The authors are also grateful for the valuable suggestions and comments by the reviewers of this article.

Availability of data and materials

All data present in this review is accessible through scientific journals and reports.

Authors’ contributions

MCMN and KB performed the systematic review. KB supervised the research and provided inputs for discussion. All authors contributed equally to the discussion, conclusion and review of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study does not require ethics committee approval or written informed consent as it relies entirely on published available data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marcelo Contardo Moscoso Naveira, Email: mnaveir1@alumni.jh.edu.

Komal Badal, Email: talktobadal@gmail.com, Email: badalk@unaids.org.

Jagadish Dhakal, Email: dhakalj@unaids.org.

Neichu Angami Mayer, Email: neidzangami@gmail.com.

Bina Pokharel, Email: pokharelb1@gmail.com.

Ruben Frank Del Prado, Email: delprador@unaids.org, Email: ruben.f.del.prado@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kleinman S, Busch M. The risk of transfusion-transmitted infection: direct estimation and mathematical modelling. Ballière’s Clinical Haematology. 2000;13(4):631–649. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Government of Nepal . Ministry of Health and Population. National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Country Progress Report Nepal. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narain JP. Three decades of HIV/AIDS in Asia. New Delhi: Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Nepal . National Planning Comission. Sustainable development goals 2016–2030. Kathmandu: National Preliminary Report; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of Nepal . Ministry of Health. National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Kathmandu: Nepal HIVision 2020 - Ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat, by 2030; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillis A, Shrestha S, Saha N. An epidemic of infectious hepatitis in the Kathmandu Valley. J Nepal Med Assoc. 1973;11(5):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Dharmadhikari A, Seage G, Raj A. Syphilis and hepatitis co-infection among HIV-infected, sex-trafficked women and girls, Nepal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):932–934. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinkel HT, Karmacharya D, Shakya J, Manandhar S, Panthi S, Karmacharya P, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C infections and an assessment of HCV-genotypes and two IL28B SNPs among people who inject drugs in three regions of Nepal. PLOS One. 2015;10(8):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuti M. The low prevalence of HBV markers in Nepal. Transact R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82:144. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhungel B, Dhungel K, Easow J, Singh Y. Opportunistic infection among HIV seropositive cases in Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2008;6(3):335–339. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v6i3.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karki S, Ghimire P, Tiwari BR, Shrestha AC, Gautam A, Rajkarnikar M. Seroprevalence of HIV and hepatitis C co-infection among blood donors in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(1):67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiwari B, Ghimire P, Kandel S, Rajkarnikar M. Seroprevalence of HBV and HCV in blood donors: a study from regional blood transfusion services of Nepal. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010;4(2):91–93. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.67026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudhamshu K, Sharma D, Poudyal N, Basnet BK. Acute viral hepatitis in pediatric age groups. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2014;52(193):687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnawal SP, Niraula SR, Agrahari AK, Bista N, Jha N, Pokharel PK. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection in Nepal. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33(2):141–145. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrestha SM, Shrestha S, Tsuda F, Sawada N, Tanaka T, Okamoto H, et al. Infection with GB virus C and hepatitis C virus in drug addicts, patients on maintenance hemodialysis, or with chronic liver disease in Nepal. J Med Virol. 1997;53:157–161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199710)53:2<157::AID-JMV8>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz GR, Riome S, Miller D, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013;13:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chander A, Pahwa V. Status of infectious disease markers among blood donors in a teaching hospital, Bhairahawa, western Nepal. J Commun Dis. 2003;35(3):188–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karki S, Ghimire P, Tiwari BR, Maharjan A, Rajkarnikar M. Trends in hepatitis B and hepatitis C seroprevalence among Nepalese blood donors. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:324–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrestha AC, Ghimre P, Tiwari BR, Rajkarnikar M. Transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Kathmandu, Nepal. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3(10):794–797. doi: 10.3855/jidc.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nepal Red Cross Society National Blood Transfusion Service . Annual Progress Report 2069/070. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nepal Red Cross Society . Annual Progress Report 2071/072. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee A, Uprety L, Chapagain M, Kafle K. Drug abuse in Nepal: a rapid assessment study. Bull Narc. 1996;48(1):11–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam L. Comments on Strang et al.'s "Heroin smoking by 'chasing the dragon': origins and history". Addiction. 1997;92(6):685–95. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09652149737665. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Shrestha S, Shrestha D, Gafney T, Maharjan K, Tsuda F, Okamoto H. Hepatitis B and C infection among drug abusers in Nepal. Trop Gastroenterol. 1996;17(4):212–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrestha SM, Tsuda F, Okamoto H, Tokita H, Horikita M, Tanaka T, et al. Hepatitis B virus subtypes and hepatitis C virus genotypes in patients with chronic liver disease in Nepal. Hepatol. 1994;19(4):805–809. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrestha SM, Shrestha S, Shreshta A, Tsuda F, Endo K, Takahashi M, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and inferior vena cava obstruction among patients with liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma in Nepal. Hepatol. 2007;22:1921–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane MA, Bradley DW, Shrestha SM, Maynard J, Cook EH, Mishra RP, et al. Recovery of a possible etiologic agent and transmission studies in marmosets. JAMA. 1984;252(22):3140–3145. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03350220046029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrestha SM, Shrestha I, Maharjan K. Family clustering of HBV infection in the household of persistent HBsAg carriers: spread of HBV by horizontal transmission. J Inst Med. 1991;13:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrestha SM. Seroepidemiology of viral hepatitis in Surkhet, Nepal. J Inst Med. 1987;9:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poudel KC, Jimba M, Okumura J, Wakai S. Emerging co-infection of HIV and hepatitis B virus in far western Nepal. Trop Doct. 2006;36:186–187. doi: 10.1258/004947506777978244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goh K, Kong K, Heng B, Oon C. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A and hepatitis B virus infection in a Gurkha Community in Singapore. J Med Virol. 1993;41:146–149. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrestha SM, Shrestha S. Chronic hepatitis B in Nepal: an Asian country with low prevalence of HBV infection. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012;33(2):95–101. doi: 10.7869/tg.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi S, Ghimire G. Serological prevalence of antibodies to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) among healthy Nepalese males - a retrospective study. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2003;1(4):251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upreti SR, Gurung S, Patel M, Dixit S, Krause K, Shakya G, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection before and after implementation of a hepatitis B vaccination program among children in Nepal. Vaccine. 2014;32(34):4304–4309. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl 1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sulkowski M, Thomas DL. Hepatitis in the HIV-infected person. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):197–208. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shrestha IL. Seroprevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus among injecting drug users from Kathmandu. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2003;1(2):101–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poudel KC, Palmer PH, Jimba M, Mizoue T, Kobayashi J, Poudel-Tandukar K. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus among HIV-positive people in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(3):277–283. doi: 10.1177/2325957413500989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawayama Y, Hayashi J, Ariyama I, Furusyo N, Kawasaki T, Kawasaki M, et al. A ten year serological survey of hepatitis A, B and C viruses infections in Nepal. J Epidemiol. 1999;9(5):350–354. doi: 10.2188/jea.9.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mesquita F, Santos MÉ, Benzaken A, Corrêa R, Cattapan E, Sereno L, et al. The Brazilian comprehensive response to hepatitis C: from strategic thinking to access to interferon-free therapy. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1132) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.European Centre fr Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis C surveillance in Europe 2013. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015.

- 43.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C - why people born from 1945–1965 should get tested. United States: CDC; 2016.

- 44.de Bruyn G, Song E. Seroepidemiology of hepatotropic viral infections in Amp Pipal, Nepal. Trop Doct. 1998;28:173–174. doi: 10.1177/004947559802800316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hannun J. AIDS in Nepal: communities confronting an emerging epidemic. New York: AmFAR in Association with Seven Stories Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golding J, Northstone K, Miller L, Davey Smith G, Pembrey M. Differences between blood donors and a population sample: implications for case-control studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1145–1156. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joffres C, Mills E, Joffres M, Khanna T, Walia H, Grund D. Sexual slavery without borders: trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7(22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Sarkar K, Bal B, Mukherjee R, Chakraborty S, Saha S, Ghosh A, et al. Sex-trafficking, violence, negotiating skill, and HIV infection in brother-based sex workers of Eastern India, adjoining Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(2):223–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman J, Decker M, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis B, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.UNDP, USAID . Being LGBT in Asia. Bangkok: Nepal Country Report; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Division for Health and Population. Opioid substitution therapy in Nepal. Bonn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH; 2016.

- 52.UNDP, Williams Institute . Surveying Nepal’s sexual and gender minorities: an inclusive approach. Bangkok: UNDP; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.UNDP . Lost in transition: transgender people, rights and HIV vulnerability in the Asia-Pacific Region. Bangkok: UNDP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ministry of Health and Population . National Centre for AIDS and STI Control. National targeted intervention operational guidelines - injecting drug users. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomson N. Harm reduction history, response, and current trends in Asia. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21(Suppl 4):113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natco Pharma. News & Announcements. 2017. http://natcopharma.co.in/about/news/. Accessed 21 Feb 2017.

- 57.Gilead Sciences, Inc . Chronic hepatitis C treatment expansion - generic manufacturing for developing countries. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Medicines Patent Pool. Medicines Patent Pool. 2015. https://medicinespatentpool.org/uploads/2015/11/MPP-HCV-License-Agreement-BMS-FINAL-Web-00000002.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2017.

- 59.Iyengar S, Tay-Teo K, Vogler S, Beyer P, Wiktor S, de Joncheere K, et al. Prices, costs, and affordability of new medicines for hepatitis C in 30 countries: an economic analysis. PLOS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lavanchy D. Chronic viral hepatitis as a public health issue in the world. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22(6):991–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mandell G, Bennett J, Mandell DR. In: Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7. Mandell JEBRD GL, editor. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blumberg BS. The discovery of the hepatitis B virus and the invention of the vaccine: a scientific memoir. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(Suppl):502–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s4.19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ministry of Health & Population . Department of Health Services. Child Health Division. National immunization program - reaching every child - comprehensive multi-year plan 2068/2072 (2011–2016) Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ministry of Health. Department of Health Services. Child Health Division. National immunization program of Nepal - reaching every village - multi-year plan of action 2007–2011. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2007.

- 65.Berger S. Hepatitis B: global status: GIDEON Informatics Inc. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization . Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016–2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tajiri K, Shimizu Y. Unsolved problems and future perspectives of hepatitis B virus vaccination. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(23):7074–7083. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shrestha S, Bhattarai M. Study of hepatitis B among different categories of health care workers. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16(2):108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhattarai S, Smriti K, Pradhan PM, Lama S, Rijal S. Hepatitis B vaccination status and needle-stick and sharps-related injuries among medical school students in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(774) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Gurubacharya D, Mathura K, Karki D. Knowledge, attitude and practices among health care workers on needle-stick injuries. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2003;1(2):91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh B, Paudel B, KC S. Knowledge and practice of health care workers regarding needle stick injuries in a tertiary care center of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2015;13:230–233. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v13i3.16813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shrestha SM. Acute sporadic viral hepatitis in Nepal. Trop Gastroenterol. 1987;8:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reynolds RD, Moser P, Acharya S, McConnell W, Andon M, Howard MP. Nutritional and medical status of lactating women and their infants in the Kathmandu valley of Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:722–728. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mertens T, Tondorf G, Siebolds M, Kruppenbacher J, Shrestha S, Mauff G, et al. Epidemiology of HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) in selected African and Asian populations. Infection. 1989;17(1):4–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01643488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shrestha SM. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B in Nepal. J Commun Dis. 1990;22:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhatta P, Thapa S, Neupane S, Baker J, Friedman M. Commercial sex workers in Kathmandu Valley: profile and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases. J Nepal Med Assoc. 1994;32(111):191–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rai SK, Shibata H, Satoh M, Murakoso K, Sumi K, Kubo T, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses in Eastern Nepal. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1994;68(12):1492–1497. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.68.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakashima K, Kashiwagi S, Noguchi A, Hirata M, Hayashi J, Kawasaki T, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus type-I, and hepatitis A, B and C viruses in Nepal: a serological survey. J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;98(5):347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manandhar K, Shrestha B. Prevalence of HBV infection among the healthy Nepalese males: a serological survey. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(6):410–413. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manandhar K, Shrestha B. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection amongst healthy Nepalese males. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19(4):145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bidya S. HBsAg carriers among healthy Nepalese men: a serological survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20(3):235–8. http://www.recoveringnepal.org.np/image/info_materials/20111103081156838553767.pdf. [PubMed]

- 82.Chiba H, Takezaki T, Neupani D, Kim J, Yoshida S, Mizoguchi E, et al. An epidemiological study of HBV, HCV and HTLV-1 in Sherpas of Nepal. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2004;5:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shah B, Bhattacharya S, Parija S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus among Bhutanese refugees residing in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2005;3(3):239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shrestha P, Bhandari D, Sharma D, Bhandari B. A study of viral hepatitis during pregnancy in Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11(3):192–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.HEPA Foundation, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Prevalence of hepatitis C in OST client.

- 86.Asian Network of People Who Use Drugs. Barriers to hepatitis C diagnosis, management and treatment among people who inject drugs in 4 Asian countries: a community led study in India, Indonesia, Malaysia & Nepal. Bangkok: Asian Network of People who Use Drugs (ANPUD); 2011.

- 87.Adhikari P, Pathak U, Uprety D, Sapkota S. Profile of ascites patients admitted in Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14(2):111–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ojha CR, Khagendra K, Shakya G. Co-infection of hepatitis C among HIV-infected population with different risk groups in Kathmandu, Nepal. Biomed Res. 2013;24(4):441–444. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Supram HS, Gokhale S, Sathian B, Bhatta DR. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection among HIV infected individuals at tertiary care hospital in Western Nepal. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2015;5(2):488–493. doi: 10.3126/nje.v5i2.12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ministry of Health and Population . National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among people who inject drugs (PWID-male) in the Eastern Terai Highway Districts (Jhapa, Morang and Sunsari) of Nepal, 2015. Teku, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ministry of Health and Population . National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among people who inject drugs (PWID) in Kathmandu Valley, 2015. Teku, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ministry of Health and Population . National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among people who inject drugs (PWIDs) in Pokhara Valley, 2015. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 93.United Nations Development Program/Department for International Development/Center for Molecular Dynamics Nepal . Draft report of four PLHIV surveys. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loewinger G, Sharma B, Karki DK, Khatiwoda P, Kainee S, Poudel K. Low knowledge and perceived hepatitis C risk despite high risk behaviour among injection drug users in Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;33:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ministry of Health . National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among female injecting drug users in Kathmandu Valley. Teku, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ministry of Health . National Centre for AIDS and STD Control. Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among people who inject drugs (PWID-male) in Western to Far Western Terai Highway Districts of Nepal. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nepal A, Kunwar B. Evidence of hepatitis C virus infection and associated treatment in Nepal. J Mol Biomark Diagn. 2016;7(2):270. doi: 10.4172/2155-9929.1000270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data present in this review is accessible through scientific journals and reports.