Abstract

Encephaloceles are rare embryological mesenchymal developmental anomalies resulting from inappropriate ossification in the skull through which herniate the intracranial contents of the sac. Occipital encephaloceles are described as giant when they are larger than the head from which they arise, and they pose a great surgical challenge. Herein, we present a case of a giant occipital encephalocele in a neonate with Chiari malformation Type 3 to highlight the problems encountered in its management and the outcome of the surgery.

KEYWORDS: Chiari malformation, encephalocele, giant encephalocele, hydromyelia, syringomyelia

INTRODUCTION

Chiari malformation (CM) Type 3 is an extremely rare anomaly, characterized by the herniation of the posterior fossa contents, including the cerebellum, brain stem, and fourth ventricle, and in some cases, the upper cervical spinal cord through a low occipital and/or upper cervical osseous defect. The incidence of encephalocele is 1/5000 live births.[1] Giant encephalocele is a rare clinical condition. Even today, it is a formidable challenge to neurosurgeons.[1,2] This is due to the amount of brain tissue, which forms the content of the encephalocele, intraoperative blood loss, and intra- and postoperative hypothermia. CM Type 3 with a giant occipital encephalocele (GOE) is rare, and to the author's knowledge, only a handful of published reports are available till date, mostly reporting a poor outcome which was contradictory in our case.[2,3,4,5]

CASE REPORT

History

A 1-day-old baby girl born at term in a peripheral hospital following cesarean section of a 36-year-old female was transferred to our neurosurgical center for further management. Antenatal diagnosis of an occipital encephalocele was established at 5 months of gestation period following a detailed scan by a fetomaternal specialist. Amniocentesis results were normal. The mother had Type 2 diabetes mellitus and two previous histories of macrosomic babies. There was neither a history of suspicious medication in the pregnancy period nor evidence of maternal infection during pregnancy.

Examination

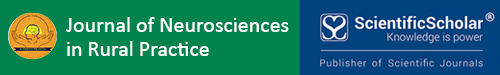

At birth, Apgar score was 10 and weight was 4.58 kg. There was no abnormality on physical examination besides a giant tense cystic mass on the posterior aspect of the head. The circumference of the swelling was 44 cm as compared to the head circumference of 33 cm. The overlying skin was stretched but well formed [Figure 1]. There was neither discernible congenital anomaly nor neurological deficit, and the hematological and biochemical parameters showed no abnormality.

Figure 1.

Preoperative appearance and position of the neonate in the operating room

Radiological findings

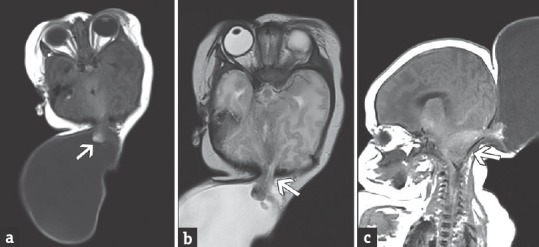

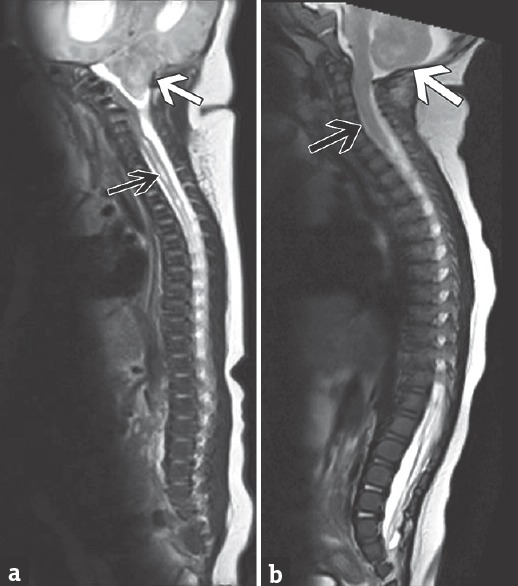

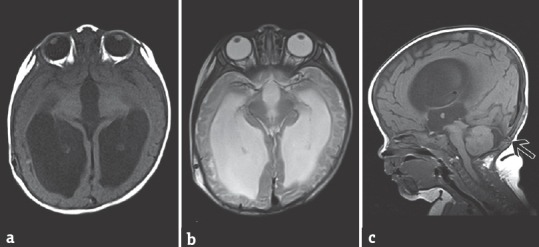

A computerized tomography (CT) scan demonstrated the encephalocele with evidence of herniation of a very thin-looking redundant brain tissue into the sac, and a defect of the occipital bone measuring 8 mm × 10 mm. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a defect at the occipital region and a large encephalocele sac with herniated right cerebellar brain parenchyma through this defect. Associated tonsillar herniation into the foramen magnum was seen. The fourth ventricle and brain stem were in the normal position. Other findings were corpus callosum dysgenesis with colpocephaly [Figure 2]. The magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) were normal. On the spine MRI, an evident syringohydromyelia was seen from C1 to T12 level [Figure 3]. This constellation of findings confers the diagnosis of a CM Type 3 with a GOE. Echocardiography and ultrasonography of the abdomen showed no abnormalities.

Figure 2.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging – T1 and (b) magnetic resonance imaging – T2 axial view preoperatively with white arrow showing giant occipital encephalocele with evidence of cerebellar tissue herniation into the sac. (c) Magnetic resonance imaging – T1 sagittal view showing the giant occipital encephalocele with Chiari malformation Type 3

Figure 3.

(a) Preoperative whole spine magnetic resonance imaging – T2 showing syringohydromyelia (black arrow) and tonsillar herniation, (b) postoperative whole spine magnetic resonance imaging – T2 at 3 months showing resolution of syringohydromyelia (black arrow) and tonsillar herniation (white arrow)

Operation

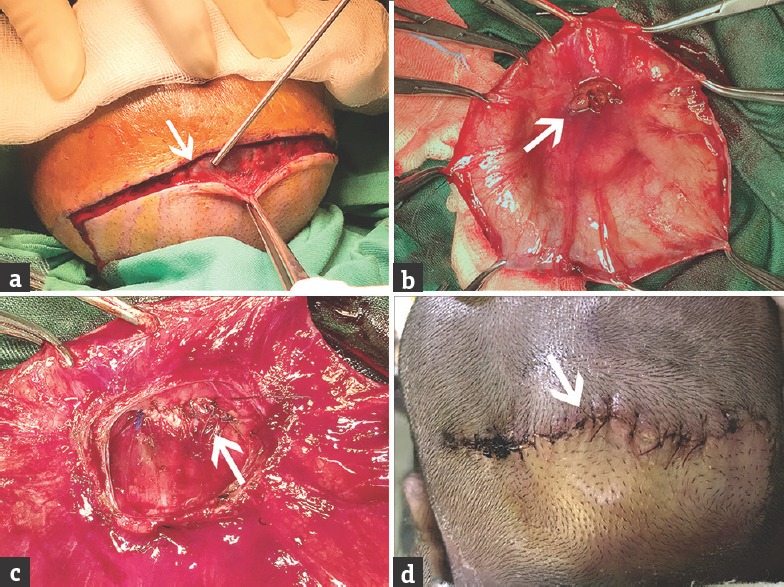

Surgery was planned to reduce the size of the swelling as well as its contents. The patient was intubated in a neutral position. Then, in prone position, the extent of scalp resection was marked out to avoid any redundant skin and dead space. A circumferential incision was placed over the sac, and the neck was dissected out. Sac was then opened, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was drained gradually. The protruded portion of cerebellum looked redundant, and hence, it was excised. A two-layered watertight closure was done for the dura, followed by scalp closure in layers [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Intraoperative images (white arrow): (a) Dissection of the flap along the marked skin margins, (b) exposure of the sac and the herniated nonviable cerebellar tissue, (c) double-layer closure of the dural defect, (d) skin closure 1 week postoperatively

Postoperative course

Postoperatively, the patient was discharged on the 7th day with a follow-up to monitor for fluid collection and the requirement for a shunt. A month following surgery, it was noted that the anterior fontanel was bulging and tense. A CT scan showed communicating hydrocephalus, which was managed with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. A postoperative MRI of the brain and spine was done 3 months later, which showed resolution of the occipital encephalocele and tonsillar herniation, with a significant radiological improvement of the syringohydromyelia [Figures 3 and 5]. At 6 months of age, the patient remains well with mild developmental delay and no neurological deficit under the pediatric neurology and neurosurgery follow-up.

Figure 5.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging – T1, (b) magnetic resonance imaging – T2 axial, and (c) magnetic resonance imaging – T1 sagittal view 3 months postoperatively showing no encephalocele and resolved tonsillar herniation

DISCUSSION

The size of occipital encephaloceles may vary from small to large masses. Nearly 15%–20% of children have additional congenital anomalies, including neural tube defects, microcephaly, CM Type 2 or 3, craniosynostosis, and syringomyelia.[2,3,5,6] For this reason, MRI coupled with MRA and MRV is the optimal investigation to visualize the contents of the sac and its relationship to venous sinuses during the surgical planning.[7]

The decision regarding surgery is dependent on various factors including the amount of neural tissue in the sac and other congenital anomalies. Surgical management of these children requires careful attention to pediatric anesthetic and surgical principles. Attention has to be given to blood and CSF loss, electrolyte imbalance, body temperature, prone position, and its associated complications.[8]

The surgical incision would depend on the shape, size, and location of the lesion. A multidisciplinary approach with a reconstructive surgeon is always beneficial in case there is inadequate skin for primary closure and skin flap rotation or advancement is required. In general, dysplastic brain tissue and meninges should be excised preserving the vascular structures.[1,6] Emphasis should be given for a two-layered watertight dural closure to prevent CSF leak. Osteogenic properties of dura can reduce the bony defect, obviating the need for cranioplasty. Surgical outcome is generally good independent of size, depending on the amount of neural tissue. A GOE with less neural tissue has excellent prognosis, as it was evident in our case.[1,9]

Nearly 60%–70% of patients with posterior encephaloceles will develop hydrocephalus requiring ventriculoperitoneal shunting.[10] It is crucial to know that hydrocephalus, which was not apparent preoperatively, can become apparent after the repair of an encephalocele. This was also the case in our patient which required a shunt postrepair.

The management of GOE needs to be tailored accordingly for every case, with the involvement of a multidisciplinary team including neurosurgeon, pediatrician, and anesthesiologist. In our case, with a tense GOE, problems encountered were essentially because of the large size and induced neonate handling, positioning in the operation theater, intubation, and blood loss during resection of the large amount of redundant skin. Well-planned and early meticulous surgery results in a satisfactory outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar V, Kulwant SB, Saurabh S, Richa SC. Giant occipital meningoencephalocele in a neonate: A therapeutic challenge. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2017;12:46–8. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.205655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulut MD, Yavuz A, Bora A, Gülşen I, Özkaçmaz S, Sösüncü E. Chiari III malformation with a giant encephalocele Sac: Case report and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49:316–9. doi: 10.1159/000365661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozinov O, Tirakotai W, Sure U, Bertalanffy H. Surgical closure and reconstruction of a large occipital encephalocele without parenchymal excision. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:144–7. doi: 10.1007/s00381-004-1020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahapatra AK. Giant encephalocele: A study of 14 patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2011;47:406–11. doi: 10.1159/000338895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mealey J, Jr, Dzenitis AJ, Hockey AA. The prognosis of encephaloceles. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:209–18. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.2.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munyi N, Poenaru D, Bransford R, Albright L. Encephalocele – A single institution African experience. East Afr Med J. 2009;86:51–4. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v86i2.46931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naidich TP, Altman NR, Braffman BH, McLone DG, Zimmerman RA. Cephaloceles and related malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:655–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdemir N, Ozdemir SA, Ozer EA. Management of the giant occipital encephaloceles in the neonates. Early Hum Dev. 2016;103:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath HD, Mahapatra AK, Borkar SA. A giant occipital encephalocele with spontaneous hemorrhage into the Sac: A rare case report. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9:158–60. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.142736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphreys RP. Encephalocele and dermal sinuses. In: Cheek WR, Martin AE, McLone DG, Reigel D, Walker M, editors. Pediatric Neurosurgery: Surgery of the Developing Nervous System. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1994. pp. 96–103. [Google Scholar]