Abstract

Purpose/Objectives:

To describe changes in health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) and to identify supportive care services used after treatment for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL) in young adults.

Design:

A longitudinal repeated measures study design was used to test the feasibility of data collection at the conclusion and 1, 3 and 6 months after the completion of treatment for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

Setting:

Participants were identified from two large comprehensive cancers in New England.

Sample:

Forty young adults with newly diagnosed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma were enrolled in the study prior to the completion of chemotherapy or radiation.

Methods:

Data were collected by interviews, standardized questionnaires, and medical record reviews.

Main Research Variables:

Health-related quality of life variables, defined as symptom distress, physical function, emotional distress, and intimate relationships, use of specific supportive care services, baseline demographic and disease related information.

Findings:

Results indicate that symptom distress improved by 1 month after treatment and remained low at 3 and 6 months. Similarly, physical function improved by 1 month after treatment. Only 12.5% of the sample had significant emotional distress at baseline and this decreased to 8% over time. Patients placed high value on their interpersonal relationships. A variety of supportive care services were used after treatment. The most common services used after treatment were related to economic issues whereas by six months services shifted towards enhancing nutrition and fitness.

Conclusion:

The results from this study suggest that HR-QOL in young adults with HL improved within 1-month after-treatment and that interest in using supportive care services was high.

Implications for Nursing

Facilitating the use of supportive care services at the end of cancer treatment appears to be an important part of helping young adults transition to survivorship.

In 2011, it is estimated that there were 8,830 new cases of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL) and 166,776 people living and receiving treatment or in remission in the United States (Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, 2010). HL affects a disproportionate number of young adults, both men and women, and the probability of long-term, disease free survival is excellent. Indeed, individuals with stage I and stage II HL receiving curative regimes have an estimated 5-year survival rate of 90–95%, which decreases to 60%−80% for those with stage III and IV disease (American Cancer Society, 2010).

A catastrophic illness such as cancer in young adults has the potential to interrupt the ability to attain expected developmental milestones such as the establishment of personal independence, development of intimate relationships with friends and marital partners and accomplish career and work goals (Roper, McDermott, Cooley, Daley, & Fawcett, 2009; Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, & Kaplan, 2000). A serious life changing event can suddenly alter a young adult’s already vulnerable self-esteem and fragile identity, which can have a negative impact on health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) (Sidell, 1997; Zebrack, 2000). Thus, it is important to gain an understanding of the impact of cancer on young adults’ HR-QOL, who may experience a deeper sense of loss compared to older adults who have greater life experience and may be more accepting of adverse events (Schroevers, Ranchor, & Sanderman, 2003). This knowledge can serve as a basis for development of interventions that are designed to enhance the transition to survivorship, minimize deleterious effects on accomplishing normal developmental tasks, and improve HR-QOL.

Conceptual Framework

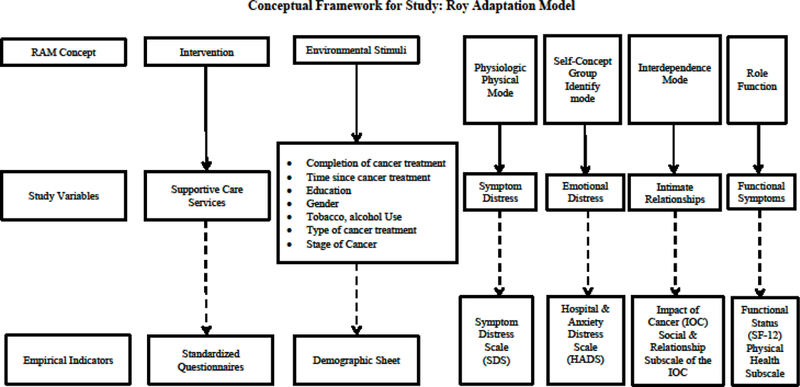

This study was guided by the Roy Adaptation Model (RAM) as shown in Figure 1 (Roy, Whetsell, & Frederickson, 2009). The RAM depicts individuals as bio-psychosocial beings who adapt to ever-changing environmental stimuli. Environmental stimuli are categorized as focal, which refers to the stimuli most immediately confronting the person; contextual, which refers to contributing factors in the situation; and residual, which refers to other unknown factors that may influence the situation. When factors making up the residual stimuli become known, they usually are considered contextual stimuli. The individual has coping processes, called regulator and cognator subsystems. The regulator subsystem functions through use of the autonomic nervous system in making physiologic adjustments to the environment, whereas the cognator subsystem controls processes related to perception, learning, judgment, and emotion. Environmental stimuli activate the coping processes. The coping processes act to produce adaptive or ineffective responses. Adaptive responses are those that promote the person’s survival, growth, reproduction, and mastery. In contrast, ineffective responses are those that do not promote these goals, thereby signaling a need for intervention. The responses are considered to take place in four bio-psychosocial modes. The physiological mode is concerned with basic needs necessary to maintain the physiological integrity of the human system. The self-concept mode is concerned with the psychic and spiritual self. The role function mode is concerned with the performance of roles based on the individuals’ position within society. The interdependence mode deals with the maintenance of satisfying affectional relationships with significant others. Collectively, the four modes of adaptation comprise HR-QOL (Nuamah, Cooley, Fawcett, & McCorkle, 1999). Nurses assess behavior and factors that influence adaptive abilities, and focus interventions on the person’s ability to expand their adaptive abilities.

Figure 1:

Conceptual Framework

The RAM concepts of interest for this study were the focal and contextual stimuli, the four bio-psychosocial modes of adaptation, and nursing interventions. Roy and Andrews (2009) postulated that focal and contextual stimuli influence the response modes. The focal stimulus was time, in relation to treatment (completion of active treatment and 1, 3, and 6 months after completion of treatment). The contextual stimuli were represented by demographic (marital status, education, gender) and clinical characteristics (stage of disease and type of cancer treatment). Biopsychosocial adaptation was represented by HR-QOL. In particular, the physiologic mode was represented by symptom distress, the self-concept mode was represented by emotional distress, the interdependence mode was represented by intimate relationships, and the role function mode was represented by functional status. Supportive care services that were being used were identified to determine what nursing interventions could augment existing services.

Literature Review

Although patients look forward to the completion of treatment, feelings of ambivalence and concerns about recurrent disease often surround the end of active treatment (Arnold, 1999; IOM, 2005, p. 10). Moreover, the end of treatment may seem to be an abrupt conclusion to what patients may regard as a safe environment of monitoring and focused care. Because oncology nurses provide care to patients with HL throughout the treatment period, they are in an ideal position to support patients by addressing survivorship issues systematically prior to the end of active treatment and throughout the transition to surveillance (Ganz & Hahn, 2008; Oeffinger & McCabe, 2006). At the present time, however, there are few data to guide clinical nursing interventions to facilitate the adaptation to living with cancer after the completion of treatment (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2005).

Only one prospective longitudinal study describing changes in HR-QOL in young adults with HL conducted in the United States could be located. Ganz et al. (2003) compared the HR-QOL for those receiving combined modality treatment (CMT) to those who received radiation alone before treatment, at six months, then annually for seven years. Ganz et al. (2003) found that those who received CMT experienced significantly more physical symptoms such as fatigue, poorer quality of life (QOL), and were more likely to be unemployed at six months compared to those who received radiation therapy alone. Most studies conducted have been cross-sectional and have examined HR-QOL issues among long-term HL survivors, defined as 5 years or greater since diagnosis (Adams et al., 2004; Bloom et al., 1993; Cameron et al., 2001; Fobair et al., 1986; Zabora, BrintzenhofeSzoc, Curbow, Hooker, & Piantadosi, 2001).

Physical symptom burden has also been associated with age. Loge (1999) reported that there was a statistically significant difference between those HL patients 60 years or older who had the lowest scores on physical scales such as bodily pain, physical functioning, and general health and role limitations. Gil-Fernandez (2003) reported that loss of appetite, problems with diarrhea, and depression were higher in those over 45 years. Greater concerns for young adult survivors of cancer who return to normal functioning soon after treatment are the long term and late effects of cancer.

Evidence supporting an increase in psychological distress among HL survivors is mixed. Cella and Tross (1986) reported that survivors did not differ significantly from non-patients in psychological distress. In fact, many survivors’ expressed positive outcomes associated with the cancer experience such as having a greater appreciation of life, and enhanced self-esteem (Cella & Tross, 1986; Yellen, Cella, & Bonomi, 1993). Other studies, however, revealed that psychological distress was higher than that of a healthy population and that up to 50% of patients reported anxiety, depression or a combination of both in the first year after diagnosis and treatment (Devlen, Maguire, Phillips, & Crowther, 1987; Kornblith et al., 1990; Norum & Wist, 1996).

Several researchers have reported disruptions in personal relationships among survivors of HL (Cella & Tross, 1986; Fobair et al., 1986; Kornblith et al., 1990). Fobair et al. (1986) identified a moderately high divorce rate (32%), problems with infertility (18%), and less interest in sexual activity (20%) among 403 HL survivors. Cella and Tross (1986) found significantly lowered intimacy motivation among 60 men HL survivors as compared to a healthy control group. In another study, Kornblith et al. (1990) noted that of 273 HL survivors, 37% reported one or more sexual problems due to decreased interest, activity or satisfaction.

Although the majority of HL survivors return to a high level of functioning, changes in social and work related function have been noted (Devlen et al., 1987; Fobair et al., 1986; Kornblith et al., 1990; van Tulder, Aaronson, & Bruning, 1994). Devlin et al. (1987) identified a decline and inadequate interest in leisure activities among HL survivors. Difficulties returning to work have been reported in up to 42% of HL survivors (Fobair et al., 1986). Problems included denial of insurance or other benefits, encouraged to leave, being fired, laid off or demoted (Fobair et al., 1986; Kornblith et al., 1990). Carpenter, Morrow, and Schmale (1989) reported that those patients who had completed treatment greater than two years compared to those less than two years experienced greater feelings of abandonment and illness uncertainty although appeared better adjusted to career plans as they moved further away from treatment. Fobair et al. (1986) reported that younger HL survivors (15–34 years) on average had a return of energy within 12 months although the median time required to resume normal activities was eight months for all ages.

Supportive care services are services that assist patients and their families in handling the physical, psychological, social, and practical problems that frequently accompany the diagnosis and treatment for cancer (Coluzzi et al., 1995). Limited research exists on the scope of services that are designed specifically for cancer survivors who have completed treatment (Ferrell, Virani, Smith, & Juarez, 2003; Tesauro, Rowland, & Lustig, 2002). Tesauro (2002) described the type of services that are available specifically for cancer survivors who have completed treatment from Comprehensive Cancer Centers within the United States. Few researchers have assessed what services are used or needed from the patient’s perspective. Gray et al. (2000) assessed the supportive care services used by women with breast cancer. Out of 731 women with breast cancer, 31% reported using at least one supportive care service (from mental health professional, dietician or physical therapist) and 34% indicated that there was at least one professional service that they would have liked to use but were unable to access. Houts et al. (1986) surveyed 629 persons with cancer to determine their views of unmet psychological, social or economic needs. Fifty-nine percent of respondents indicated at least one unmet need. The most common unmet need was dealing with the emotional aspects of the cancer diagnosis. Younger age, being employed, student status, more advanced stage of cancer, and having received chemotherapy was associated with use of and need for supportive care services (Gray, Goel, & Fitch, 2000; Houts, Yasko, Kahn, Schelzel, & Marconi, 1986).

The existing gaps in knowledge about HR-QOL after treatment for HL illustrate the need for further clinical research data to guide nursing interventions to facilitate adaptation to living with cancer after the completion of treatment for HL. Longitudinal studies designed to examine HR-QOL in young adults after completion of treatment for HL are critical to capture changes over time and to direct the timing of clinical interventions (Murdaugh, 1997). Thus, the aims of the current study are to: (1) describe changes in adaptation, conceptualized as components of HR-QOL of young adult HL patients at the end of cancer treatment and one, three, and six months after the completion of treatment, and (2) identify supportive care services used at baseline and end of treatment. This study extends the literature by examining changes in HR-QOL over time in young HL survivors up to six months following treatment.

Methods

Research Design

This study used a longitudinal repeated measures design.

Participants/Sample

Participants were identified from two academic medical centers in New England. To determine sample size, historical data for new patient consults in 2000 and 2001 were reviewed at the two sites for new patient HL consults. It was estimated that we would have a total of 40–60 potentially eligible patients for 2003. Therefore, our accrual goal was projected to be 45 patients over one year to ensure that there would be at least 35 participants eligible for evaluation. Data were collected after treatment completion (defined as 1 week before or 1 week after last cancer treatment), and 1, 3, and 6 months after treatment. Patients were enrolled in the study over one year.

Inclusion criteria for patients were: English speaking, between 21 and 40 years of age with newly diagnosed HL (early stages I A/B, II A, or III A or late stage; IIB, IIIB, IV A/B). Participants were enrolled in the study prior to the completion of chemotherapy or radiation. Participants were not eligible if they have had a prior cancer diagnosis, had recurrent HL, received treatment at another facility, or if they were unable to complete questionnaires due to language barriers or had major organic or psychiatric disorders that would preclude an ability to provide informed consent.

Of 126 patients originally screened to be included in the study, 79 patients were ineligible. Twenty-six (33%) were ineligible due to their age (being either too old or too young), twenty-three (29%) were not newly diagnosed and were seeing a consult for relapsed disease, twenty (25%) were newly diagnosed but were receiving their treatment at another facility, three (4%) were non English speaking or missed screening and finally, seven (9%) were eligible but refused participation. Their stated reasons were they were: too busy, too anxious, and just unwilling. Most of those who refused participation were female (n=4) and the mean age of refusals was 29 years of age. Of the remaining 47 registered patients, data generating did not begin for 7 due most frequently to progressive disease that occurred after enrollment.

The sample size for each data collection period was 40 at baseline (time 1), 38 (95%) at one month (time 2), 37 (92.5%) at three months (time three), and 38 (95%) at six months (time 4). Two participants withdrew consent after completing survey one, resulting in an attrition rate of 5%. A cohort of 38 patients completed all surveys, with the exception of one who had missing information at time three.

Survey Instruments

Demographic, and supportive care services data were collected by a standardized questionnaire that has been used in previous research (Degner & Sloan, 1992; Degner & Sloan, 1995). Clinical data (cancer stage and type of treatment) were collected by a medical chart review.

Physical symptom distress was measured by the Symptom Distress Scale (SDS). The SDS is a 13 item self-report questionnaire scored on a 5-point Likert Scale measuring distress experience relating to the severity of 11 symptoms and the frequency of two symptoms. This SDS asks for symptom scoring on the day the questionnaire was administered and took approximately five minutes to complete. The 11 symptoms include nausea, appetite, insomnia, pain, fatigue, bowel pattern, concentration, appearance, outlook, breathing, and cough. Additionally nausea and pain is reported by frequency separately. A total score is obtained by summing the 13 items; total scores range from 13, indicating little distress, to 65, indicating severe symptom distress. Cronbach alpha internal reliability coefficients in newly diagnosed cancers were .80 and .81 respectively using the SDS scale (Degner & Sloan, 1992; Degner & Sloan, 1995). Content, construct, and criterion validity have also been reported for the SDS in the cancer population (McCorkle, Cooley, & Shea, 2003). Cronbach alphas for the SDS in this study were 0.76, 0.82, 0.84, and 0.81 for Baseline, 1 Month, 3 Months, and 6 Months, respectively.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) measured emotional distress. The HADS is a 14 item, self-administered measure completed in about 5–10 minutes (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983 ). This instrument has also been found to be a reliable instrument for measuring anxiety and depression in survivors in the outpatient setting (Fossa, Dahl, & Loge, 2003; Osborne, Elsworth, & Hopper, 2003; Schofield et al., 2003; Smith, Selby, & Velikova, 2002). A summative score is obtained by adding the items. Cut-scores are available to assist in identification of those who need further assessment and intervention. Scores range from 0 to 21 for anxiety and 0 to 21 for depression. A score of 0 to 7 for either subscale is regarded as being in the normal range, a score of 11 or higher indicates probable presence (‘caseness’) of the mood disorder and a score of 8 to 10 being suggestive presence of the respective state (Snaith, 2003). The HADS was designed specifically to assess these disorders in medically ill patients including those with cancer and can be used to monitor changes over time. Its rating system is based on a four-point format and asks how the patient has felt in the past week. Authors report item-to-subscale reliability correlations as being between 0.41 to 0.76 for the anxiety items and 0.3 to 0.6 for depression items (Frank-Stromborg & Olsen, 1997). Researchers have reported internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of those with testicular cancer to be 0.85 for HADS-Anxiety and 0.82 for HADS-Depression (Fossa et al., 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha for the depression subscale of the HADS for the four time points of this study (baseline, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months) were 0.62, 0.81, 0.82, and 0.85. The Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety subscale of the HADS for the four time points of this study (baseline, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months) were 0.80, 0.86, 0.76, and 0.82.

Intimate relationships was measured by the social and relationship scale of the Impact of Cancer (IOC). The IOC is a 41 item self-administered measure developed to measure the HR-QOL of long-term cancer survivors (Zebrack, Ganz, Benrnaards, Petersen, & Abraham, 2006). Time for completion is about 10 minutes. Scoring is on a 5 point Likert scale, 1 defined as strongly disagree to 5 defined as strongly agree. This measurement consists of 6 thematic domains, physical, psychological, existential, social, meaning of cancer, and health worry. Additional items were included for those who were married or in long-term relationships and for those who were currently employed. Internal consistency reliability coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.67 – 0.89 among 193 long-term survivors including 25% with lymphoma (Zebrack et al., 2006). The revised IOC, version 2 (IOCv2), has been developed since the completion of this study following evaluation and refinement of the original scale (Crespi, Ganz, Petersen, Castillo, & Caan, 2008). Two questions from this survey were recommended for use to measure intimate relationships namely: “I place a higher value on my relationships with family or friends than I did before having had cancer.” and “I feel a special bond with people with cancer.” (B.J. Zebrack personal communication, August 1, 2007).

Functional status was measured by the physical health portion of the SF-12 Health Survey (Ware, Turner-Bowker, Kosinski, & Gandek, 2002). Administration time can range from 5 to 10 minutes. The instrument has eight concepts: physical function, role-limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. The items of the SF-12v2 are aggregated to provide two summary measures; physical and mental health. Scale scores below 50 indicate below average health status. Norm based scoring for the US population and for those with chronic illness is available (Ware et al., 2002). Test Retest correlation for physical and mental health was .89 and .76, respectively.

Procedures

Identification of potential participants was accomplished by reviewing the electronic appointment scheduling system for current HL patients and those who were scheduled for new consults at one site. Patients were approached after the oncology clinician was notified by a research representative. The research representative provided the patient with a waiver letter and a consent form when it was determined that a patient was eligible for the trial. If the patient agreed to meet with a research representative, the protocol was explained and informed consent was obtained. Once consent was obtained, arrangements were made for a future telephone interview and the questionnaires were given to the patients as a reference to facilitate the telephone interview. If the patient was undecided about participation in the study, the research representative contacted the patient at a future date with patient permission. For those patients enrolled offsite, the off-site principal investigator identified and provided a potential patient with a waiver letter and consent. A research representative was contacted by the off-site principal investigator and arrangements were made to review eligibility, explain the protocol, and consent the patient. Approval from the Institutional Review Board was obtained for both sites.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for this analysis including frequencies, means, medians, and standard deviations to describe the demographic variables, clinical characteristics, and supportive care services used at each timepoint by young adults with HL. All measures of HRQOL are described for each instrument score measuring the physical, psychological, functional, and intimate relationship components of HRQOL at each time point. Non-parametric Friedman tests were used to determine differences between the means over time and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests was used for the four pairwise comparisons. To protect against error, the Bonferroni correction of 0.0167 based on a desired level of significance of .05 was used. Additional analyses were done to explore any gender, marital, and type of treatment differences in the domains of HR-QOL.

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

The final sample consisted of 40 young adult survivors of HL ranging in age from 21–40 years (M = 30.9 years, SD = 5.8; Table 1). The sample was primarily female (60%), married (63%), Caucasian (90%), and lived with children (55%). Only 10% lived with a parent and 63% were married or living with a marital partner. Approximately 88% were employed or earning income within the last 12 months, and 10% were fully retired from paid employment. Eighty-three percent of the sample had stage I or stage II HL and 17% had stage III or stage IV. The majority of the sample (58%) received chemotherapy alone; 5% received radiation therapy alone and 37% received combined chemotherapy and radiation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline (N=40)

| Characteristics | Sample Characteristics: N=40 | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Mean = 30.41 SD = 5.701 | ||

| Education | |||

| High School Graduate or some college | 13 | 31.7% | |

| College Graduate or advanced degree | 28 | 68.3% | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 16 | 39% | |

| Marital Status | Never Married | 15 | 38% |

| Married or Living with a Partner | 25 | 63% | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic – White | 37 | 90% | |

| Other | 4 | 10% | |

| Stage of Disease | |||

| Early | 36 | 88% | |

| Late | 5 | 12% | |

| Treatment | |||

| Chemotherapy Only | 24 | 59% | |

| Radiation Only | 2 | 5% | |

| Chemotherapy and Radiation | 15 | 36% | |

Physical Distress

Analysis revealed that distressing and bothersome physical symptoms improved significantly from one to six months following treatment. Overall improvement in physical symptoms showed significantly lower mean scores of physical distress at all timepoints (p=< .0001) compared to baseline. Data were approximately normally distributed at baseline only; therefore the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests were used in lieu of parametric statistics to compare timepoints. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in symptom distress between baseline and one month (p=<.0001).

Dichotomous groups were created to delineate those with moderate to severe physical distress, indicated by an SDS score of 25 or higher. Analysis revealed that 20 HL survivors (50%) reported moderate to severe distress at baseline, and four HL survivors (11%) reported moderate to severe distress at both one and six months increasing to six reported cases (16%) at 3 months.

Emotional Distress

Examination of emotional distress demonstrated an overall significant difference from end of treatment to 6 months following treatment using the Freedman Test (p = 0.000). Pairwise comparisons were performed that showed significant improvements in total HADS depression and anxiety scores from end of treatment to 1 month following treatment (p= .006). Emotional distress was demonstrated by combined cut-off scores at or above moderate (8 or higher) to severe (11 or higher) levels of HADS anxiety and depression scores, respectively. Only 12.5% of the sample had severe emotional distress or anxiety at baseline and this decreased to 7.9% by 6 months after treatment. Although the incidence of severe anxiety decreased to 2.6% at 1 month, it continued to increase to 5.4% at 3 months and slightly at 6 months. Mean scores of anxiety and depression were all within normal range except for baseline. Depression scores improved significantly from baseline to one month (p= .010) but there were no significant improvement in anxiety levels (p=.029) for the same data collection points based on the Bonferroni correction levels of .0167.

Intimate Relationships

Intimate relationships were explained by finding the mean of the first two questions included in the activities and relationships scale of the Impact of Cancer (IOC). The average mean score for both questions increased slightly from baseline to six months, although the analysis revealed that the only significant difference in scores (p=.0003) was from end of treatment to 1 month when participants were asked if they developed a special bond with people with cancer.

Functional Status

Functional status measured by the physical health portion of the SF-12 scale significantly improved overall from end of treatment to 6 months using the Freedman Test (p = 0.000). There was a significant increase in scores from end of treatment to 1 month only (p = 0.000) for pairwise comparisons.

Supportive Care Services

Sixty-eight percent (n=27) of HL survivors used one or more services at baseline but the use of services declined somewhat to fifty-five percent (n=21) at six months. Twenty-three participants had questions regarding employee rights, health insurance, disability, and other legal and financial information at baseline declining to 16 inquiries at six months. Participation in emotional support groups (n=7) were frequently used at baseline and included professional and peer counseling (15%). Participation in health behavior programs (n=10) such as nutrition and exercise programs were often used at baseline (22%). Different forms of physical therapy (n=6) were used at baseline, including pain management and physical, and alternative therapies (13%). Supportive care services declined over time from 46 inquiries at baseline to 40 inquiries at six months. Whereas economic inquiries declined at six months the use of health behavior programs, especially fitness programs, increased at six months.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to examine changes in adaptation, conceptualized as components of HR-QOL of young adult HL patients: at the end of active treatment and at 1, 3, and 6-months after the completion of treatment and identified supportive care services used after treatment. The results of this study reveal that physical symptoms as measured by the SDS significantly improved as soon as one month after treatment from a mean of 25 at baseline, indicating moderate distress to 19.3 at 6 months, indicating low distress. This finding differs from previous studies. In a study of 246 HL survivors, Ganz (2003) reported that SDS scores were significantly higher (worse) for all HL patients at 6 months and did not return to baseline until 1 year after treatment. However, Ganz found that symptom distress was significantly lower for those who received chemotherapy alone compared to those who received CMT. In fact, we found that all of those HL survivors (n=4) who reported severe physical symptom distress at 6 months received CMT. The finding that the majority of HL patients in this study (59%) received chemotherapy only and had early stage disease (88%) may have contributed to the significant improvement in physical symptoms so soon after treatment completion. Thus, in this study significant improvements in symptom distress may be attributed to most participants not receiving both radiation and chemotherapy treatment. This finding is consistent with the findings from two earlier studies of HL patients who received CMT and experienced a greater delay in the return of energy levels, fatigue, and dyspnea compared to those receiving less intense therapy (Fobair et al., 1986; Ganz et al., 2003). Furthermore, other researchers investigating HL survivors have reported that multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, poor concentration, sleep disturbances, dyspnea, nausea, and pain are common and often persist long after completion of CMT treatment (Fossa, Vassilopoulou-Sellin, & Dahl, 2008; Greil et al., 1999). Additionally, supportive care services including symptom management have improved significantly in the past10 years.

The results of this study indicate that HL survivors’ psychological well-being is not significantly compromised. Mean scores for depression and anxiety were all within normal range and improved significantly from baseline to six months. In this study of young adult HL survivors severe depression was not reported by any of the participants at 6 months. These findings are consistent with other investigators. Loge (1997) found that HL survivors younger than 29 reported less depression than those older than 50 years. Kornblith (1998) also reported that HL survivors younger than 40 years had lower levels of depression compared to older HL survivors. Katon (2003) suggested that older adults may experience a heightened awareness of physical symptoms that can impair HRQOL and can be associated with depressive symptoms.

Functional limitations can range from difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living such as walking or lifting to performing activities such as shopping, attending social events, visiting friends, or earning a living. Factors such as older age, physical symptoms, fatigue, and psychological distress significantly predicted disability in a study of 459 HL survivors. Due to these factors HL survivors were twice as likely to be permanently disabled compared to the general population (Abrahamsen, Loge, Hannisdal, Holte, & Kvaloy, 1998). Contrary to these findings, not only did HL survivors in this study show improvement in physical and functional assessments as soon as one month after treatment, they continued to improve further away from treatment. Carpenter (1989) reported similar findings in which HL survivors were better adjusted in career plans compared to those who were closer to treatment. In a longitudinal study of 120 HL survivors, Devlen (1987) reported that for those survivors who did not remain in work during treatment, 24% returned to work within six to eleven months and an additional 19% returned to work at twelve months or more. As more survivors are able to work during treatment or return to work soon after treatment because of advances in the treatment and management of HL they are able to maintain financial independence and possibly improve outlook and quality of life through work.

The financial obligations of survivors as well as maintaining health insurance coverage may also have an influence on HL survivors’ desire to work during treatment or return to work soon after treatment regardless of distressing physical symptoms. In fact, Zebrack (2007) examined the needs of young adult cancer survivors and reported that 59% of respondents ranked adequate health insurance as their first or second most important need, which may be an incentive to return to work before full recovery. Alternatively, other researchers have found that some survivors who experienced a reduction in energy levels or who were less interested in professional work pursuits, placed more importance on participating in leisure activities and sport regardless of distressful symptoms (Bloom, Hoppe, Fobair, & Cox, 1988; Joly et al., 1996).

HL survivors in this study consistently placed a high value on relationships with family and friends compared to before having cancer. Fletchner (1998) reported that for those HL survivors who had partners, 39% believed their relationship was more intense after diagnosis and only 15% experienced a worsened relationship or separation. The implication that can be taken from our study is that survivors increasingly valued their relationships with family and friends when they were furthest away from treatment at six months. Not only do close and positive interpersonal relationships with friends and family contribute to improved coping and adjustment to cancer, but social support from a spouse has been associated with improved survival (Andersen, 1992; Wortman & Dunkel-Schetter, 1979). It remains unclear when the best time for couple counseling should be but our study revealed that scores related to intimacy and social support were lowest one month to three months after treatment. This may suggest that couple focused interventions should be initiated before treatment completion when patients and families are more accessible to professional counselors and those at risk for deteriorating relationships demonstrating a lack of communication, loss of intimacy, and negative expressions of criticism can be identified.

It is not surprising that a large percentage of inquiries pertained to the economic burden of cancer. Out of pocket expenses for prescription drugs, transportation, inability to work resulting in a loss of income, expenses related to co-insurance and co-payment, or lost caregiver wages are some of the socioeconomic burdens that cancer survivors experience. Personal bankruptcy or the filing of a petition to protect against creditors is common in those with chronic illness, including those with cancer (Himmelstein, Warren, Thorne, & Woolhandler, 2005a, 2005b). Treatment can often create lapses in employment and unless survivors have a safety net, even a brief illness can be financially devastating.

In a study of HL survivors, participants were randomized to one of four groups to determine if psychological and social functioning could be improved through education intervention or a peer support group. The education group showed improvements in anxiety and treatment problems but the peer support group showed no significant changes supporting the argument that professional guidance may be more appropriate (Jacobs, Ross, Walker, & Stockdale, 1983). A combination of psychosocial interventions such as stress management, behavioral training, and cognitive therapy as well as nutritional education is thought to provide longer lasting benefit and greater emotional support (Fawzy, 1999; Rehse & Pukrop, 2003).

In an intervention study of HD survivors who participated in an exercise intervention, a significant reduction in physical, mental, and total fatigue as well as increased exercise tolerance was reported (Oldervoll, Kaasa, Knobel, & Loge, 2003). The number of young survivors in our study doubled in their reported use of services relating to physical fitness activities from baseline to six months after treatment which may also have contributed to improved quality of life. In a recent study of 221 cancer survivors who participated in a 12-week community based exercise program, investigators found improvements in fatigue, insomnia, physical function as well as being a safe and effective means for improving overall health (Roajotte et al., 2012).

The RAM was a useful guide for this study in that the concepts of this nursing conceptual model provided a structure for the literature review and led to selection of components of HRQOL that are amenable to nursing assessment and intervention. Furthermore, the RAM proposition that stimuli influence responses in the modes of adaptation led to a longitudinal study design and our analysis of changes in the components of HRQOL over time. The finding that some components of HRQOL changed over time provides indirect support of that RAM proposition.

Limitations

Generalization of the present study results is limited by use of a small convenience sample of HL survivors from a major academic medical center that enrolls patients onto clinical trials not offered at other centers. As a consequence, patients seeking treatment are well versed and knowledgeable in their disease state and often are of higher socioeconomic status than more diverse populations. Socioeconomic factors can be strong predictors of health status. These demographic factors may account for better health and HR-QOL so soon after treatment in our population of HL survivors. Our sample of patients may also have a greater ability to access supportive care services such as professional counseling, exercise and nutrition programs, and physical therapy during treatment which may have contributed to a more speedy recovery after treatment.

Another limitation of this study is the IOC survey used to measure intimate relationships. This survey was refined and evaluated by the developer during the course of this study which resulted in a significant change to the instrument. As a consequence, this survey included only two remaining questions to measure intimate relationships; therefore it was not possible to adequately describe these outcomes. Manne and Badr (2008) suggested that in addition to taking a dyadic approach in methodology and research design when studying couple adaptation to a cancer diagnosis, a multi-method approach should be implemented using both observational designs and daily diaries that address the needs of both patient and spouse and enhance communication and understanding of the experience. Understanding the dynamics of intimate relationships in cancer survivors may require the use of a qualitative approach .which may be more effective than a survey type inquiry.

Implications for research, practice and policy

In addition to providing a longitudinal study describing changes in HR-QOL this study will be helpful in identifying interventions that can promote healthy behaviors and positive lifestyle changes resulting in improved HR-QOL. Lifestyle changes such as attention to diet and increased physical activity can be initiated during treatment to prevent sedentary behaviors that are common in this population following treatment. Cancer patients are quite accessible during treatment and by providing on-site activities that are convenient, inexpensive, and useful for promoting behavior change, such as nutrition consults and couple counseling, initiation can begin early. Ideally these services would be covered by insurance. Patients often desire further knowledge that will improve their physical and psychological well-being. On site patient participation in cancer support programs in an academic medical center can be a challenge for providers because often patients come from long distances and are unable to extend visits for various reasons, such as feeling ill, work or family obligations, or just anxious to return home, but opportunities do exist. It is encouraging that many supportive care services were used at the end of treatment in this study, some decreasing while others increased based on need and appropriate timing. Although not all patients used services, many used more than one service at a time.

On a policy level, these results provide insight as to the economic burden of cancer for patients. Opportunities for accommodation in the workplace as well as legal assistance or opportunities for short-term disability can significantly improve the HR-QOL of HL survivors. Occupational health professionals should also be at the table to provide opportunities for collaboration and input. It is essential to identify individual, disease, and work-related factors that will predict and assist the survivor to manage the physical and psychological consequences of treatment for both those who continue to work and those who choose not to or are unable to return to work.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Health-Related Quality of Life Domains Over Time (N = 40, 38, 37, 38)

| Variable (Possible Score Range) |

Conclusion of Treatment M (SD) N = 40 |

1 Month After Treatment M (SD) N = 38 |

3 Months After Treatment M (SD) n = 37 |

6 Months After Treatment M (SD) N = 38 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom distress(13–65) | 25.0 (6.3) | 20.1 (4.6) | 19.7 (5.6) | 19.3 (5.1) |

| Emotional distress | ||||

| Anxiety (0–21) | 5.3 (3.7) | 4.4 (3.7) | 4.1 (2.9) | 4.2 (3.5) |

| Depression (0–21) | 3.5 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.9) | 2.2 (2.6) | 1.8 (2.4) |

| HADS | 8.9(5.1) | 7.0(6.1) | 6.3(5.0) | 6.0(5.4) |

| Functional status Physical (50 Average) | 43.4 (8.3) | 48.4 (7.3) | 50.5 (8.4) | 51.3 (7.0) |

| Higher value relationships with family & friends (1–5) | 4.0 (0.8) | 3.9(1.0) | 3.9(1.0) | 4.1(0.9) |

| Special bond with people with cancer (1–5) | 3.6(1.0) | 4.0 (.8) | 3.8 (.9) | 3.7 (1.0) |

| Combined | 4.0(0.8) | 4.0(0.7) | 3.9(0.8) | 3.9(0.7) |

Table 3.

Frequencies for Supportive Care Services Over Time ((N = 40, 38, 37, 38)

| Type of Service | Conclusion of Treatment | 1 Month After Treatment | 3 Months After Treatment | 6 Months After Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=46 | % | n=42 | % | n=35 | % | N=40 | % | |

| Economic Inquiries | 50% | 50% | 37% | 40% | ||||

| Inquires about employee rights | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Inquiries about health insurance | 9 | 10 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Inquiries about legal/financial issues | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Disability | 9 | 6 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Emotional Support | 15% | 15% | 14% | 10% | ||||

| Peer counseling | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Professional counseling | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Health Behaviors | 22% | 28% | 40% | 42% | ||||

| Nutrition | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Fitness | 6 | 11 | 11 | 12 | ||||

| Physical Therapy | 13% | 7% | 9% | 8% | ||||

| Pain management | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Physical therapy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Alternative therapy | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

Key Points:

Supportive care services appear to be an important aspect of the transition to survivorship.

Supportive care needs appear to change over time from an emphasis on economic issues to enhancing wellness through nutrition and fitness programs

Information about the HR-QOL of young adults with HL following active treatment is essential to begin building a base for clinical interventions that promote the transition to survivorship.

Patients place a high value on their relationships with family and friends.

Acknowledgements:

Christine A. Coakley, RN, MPH, Kecia Boyd, RN, BSN who recruited subjects and collected data at DFCI and Dr. Ronald Takvorian who identified patients for enrollment at MGH. Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute 1 U56 CA11863502, Principal Investigators Karen M. Emmons and Adam Colon-Carmona, (Kristin Roper, Pre-doctoral Fellow, University of Massachusetts-Boston, PhD Program in Health Policy, Cancer Nursing and Health Disparities).

Supported in part by Oncology Nursing Foundation 2004 Novice Researcher Mentorship Grant, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute 2004 Friends Grant (Kristin Roper, PI)

Footnotes

Work completed from the Phyllis F. Cantor Center, Research in Nursing and Patient Care Services, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Contributor Information

Kristin Roper, Phyllis F. Cantor Center, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Mary E. Cooley, Phyllis F. Cantor Center, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts-Boston, Boston, MA.

Mark Powell, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Kathleen McDermott, Research in Nursing and Patient Care Services, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Sarah Green, Phyllis F. Cantor Center, Research in Nursing and Patient Care Services, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Jacqueline Fawcett, University of Massachusetts, Boston, Boston, MA.

References

- Abrahamsen AF, Loge JH, Hannisdal E, Holte H, & Kvaloy S (1998). Socio-medical situation for long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: a survey of 459 patients treated at one institution. Eur J Cancer, 34(12), 1865–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MJ, Lipsitz SR, Colan SD, Tarbell NJ, Treves ST, Diller L, et al. (2004). Cardiovascular status in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease treated with chest radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol, 22(15), 3139–3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2010). Detailed guide: Hodgkin Disease how is Hodgkin Disease staged? . Retrieved August 31, 2010, from http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_3x_How_Is_Hodgkin_Disease_Staged.asp

- Andersen B (1992). Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of life. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 60(4), 552–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EM (1999). The cessation of cancer treatment as a crisis. Social Work in Health Care, 29(2), 21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom Fobair, P, Gritz E, Wellisch D, Spiegel D, Varghese A, et al. (1993). Psychosocial outcomes of cancer: a comparative analysis of Hodgkin’s disease and testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol, 11(5), 979–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom Hoppe, R. T, Fobair P, & Cox, RS (1988). Effects of treatment on the work experiences of long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 6(3–4), 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CL, Cella D, Herndon Ii JE, Kornblith AB, Zukerman E, Henderson E, et al. (2001). Persistent symptoms among survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: An explanatory model based on classical conditioning. Health Psychol, 20(1), 71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter PJ, Morrow GR, & Schmale AH (1989). The psychosocial status of cancer patients after cessation of treatment. J Psychosocial Oncol, 7(1–2), 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, & Tross S (1986). Psychological adjustment to survival from Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(5), 616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi PH, Grant M, Doroshow JH, Rhiner M, Ferrell B, & Rivera L (1995). Survey of the provision of supportive care services at National Cancer Institute- designated cancer centers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 13, 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Castillo A, & Caan B (2008). Refinement and Psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100(21), 1530–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner LF, & Sloan JA (1992). Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play?. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45, 941– 950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner LF, & Sloan JA (1995). Symptom distress in newly diagnosed cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 10, 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlen J, Maguire P, Phillips P, & Crowther D (1987). Psychological problems associated with diagnosis and treatment of lymphomas. II: Prospective study. Br Med J 295(6604), 955–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy FI (1999). Psychosocial interventions for patients with cancer: What works and what doesn’t. European Journal of Cancer, 35(11), 1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Virani R, Smith S, & Juarez G (2003). The role of the oncology nurse to ensure quality care for cancer survivors: A report commissioned by the National Cancer Policy Board and Institute of Medicine. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flechtner H, Ruffer JU, Henry-Amar M, Mellink WA, Sieber M, Ferme C, et al. (1998). Quality of life assessment in Hodgkin’s disease: a new comprehensive approach. First experiences from the EORTC/GELA and GHSG trials. EORTC Lymphoma Cooperative Group. Groupe D’Etude des Lymphomes de L’Adulte and German Hodgkin Study Group. Ann Oncol, 9 Suppl 5, S147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fobair P, Hoppe RT, Bloom J, Cox R, Varghese A, & Spiegel D (1986). Psychosocial problems among survivors of Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol, 4(5), 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossa Dahl Loge (2003). Fatigue, anxiety, and depression in long-term surviors of testicular cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 1249–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossa, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, & Dahl, AA (2008). Long term physical sequelae after adult-onset cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 3, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Stromborg M, & Olsen SJ (1997). Instruments for clinical health-care research (2nd ed.). Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, & Hahn EE (2008). Implementing a surviorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(5), 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, Moinpour, C. M, Pauler DK, Kornblith AB, Gaynor ER, Balcerzak SP, et al. (2003). Health status and quality of life in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s disease treated on Southwest Oncology Group Study 9133. J Clin Oncol, 21(18), 3512–3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Fernandez JJ, Ramos C, Tamayo AT, Tomas JF, Figuera A, Arranz R, et al. (2003). Quality of life and psychological well-being in Spanish long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: results of a controlled pilot study. Ann Hematol, 82, 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RE, Goel V, & Fitch MI (2000). Utilization of professional supportive care services by women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 64, 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil R, Holzner B, Kemmler G, Kopp M, Buchowski A, Oberaigner W, et al. (1999). Retrospective assessment of quality of life and treatment outcome in patients with Hodgkin’s disease from 1969 to 1994. Eur J Cancer, 35(5), 698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, & Stovall E (2005). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein DU, Warren E, Thorne D, & Woolhandler S (2005a). Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Affairs, W5-63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy W5-63.- (2005b). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn SB, Schelzel GW, & Marconi KM (1986). Unmet psychological, social, and economic needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer, 58, 2355–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. (2005, p. 10). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C, Ross RD, Walker IM, & Stockdale FE (1983). Behavior of cancer patients: A randomized study of the effects of education and peer support groups. American Journal of Clinical Oncology Clinical Trials, 6, 347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly F, Henry-Amar M, Arveux P, Reman O, Tanguy A, Peny AM, et al. (1996). Late psychosocial sequelae in Hodgkin’s disease survivors: a French population-based case-control study. J Clin Oncol, 14(9), 2444–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ (2003). Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. (1990). Quality of life assessment of Hodgkin’s disease survivors: a model for cooperative clinical trials. Oncology 4(5), 93–101; discussion 104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith AB, Herndon JE 2nd, Zuckerman E, Cella, D. F, Cherin E, Wolchok, S, et al. (1998). Comparison of psychosocial adaptation of advanced stage Hodgkin’s disease and acute leukemia survivors. Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Ann Oncol, 9(3), 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. (2010, August 31, 2010). Lymphoma facts and statistics from leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma facts: 2009–2010. from http://www.leukemia-lymphoma.org/all_page?item_id=8312

- Loge JH, Abrahamsen AF, Ekeberg O, Hannisdal E, & Kaasa S (1997). Psychological distress after cancer cure: a survey of 459 Hodgkin’s disease survivors. Br J Cancer, 76(6), 791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge JH, Abrahamsen AF, Ekeberg O, & Kaasa S (1999). Reduced health-related quality of life among Hodgkin’s disease survivors: a comparative study with general population norms. Ann Oncol, 10(1), 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, & Badr H (2008). Intimacy and relationship processes in Couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer, 112(11 suppl), 2541–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle, R, Cooley, M, & Shea, J. A. (2003). A User’s Manual for the Symptom Distress Scale.

- Murdaugh C (1997). Health-related quality of life as an outcome in organizatinal research. Med Care 35(11), NS41–NS48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norum J, & Wist E (1996). Psychological distress in survivors of Hodgkin’s disease. Support Care Cancer, 4(3), 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuamah IF, Cooley ME, Fawcett J, & McCorkle R (1999). Testing a theory for health-related quality of life in cancer patients: A structural equation approach. Res Nurs Health, 22(3), 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger KC, & McCabe MS (2006). Models for delivering survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(32), 5117–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldervoll LM, Kaasa S, Knobel H, & Loge JH (2003). Exercise reduces fatigue in chronic fatigued Hodgkins disease survivors--results from a pilot study. Eur J Cancer, 39(1), 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, & Hopper JL (2003). Age-specific norms and determinants of anxiety and depression in 731 women with breast cancer recruited through a population-based cancer registry. European Journal of Cancer, 39, 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehse B, & Pukrop R (2003). Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Educ Couns, 50(2), 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS, Gregerson L, Leiserowitz A, & Syrjala KL (2012). Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper K, McDermott K, Cooley ME, Daley K, & Fawcett J (2009). Health-related quality of life in adults with Hodgkin’s disease: the state of the science. Cancer Nurs, 32(6), E1–17; quiz E18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C, Whetsell MV, & Frederickson K (2009). The Roy adaptation model and research. Nursing Sicence Quarterly, 22(3), 209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, & Kaplan. (2000). Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry: Theories of Personality and Psychopathology Erikson Erik H. In. Chapter 6 (7th ed.). Philidelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PEPN,B, Thompson, J. F, Tattersall, M. H, Beeney, L. J, & Dunn, S M (2003). Psychological responses of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer. Annals Oncology, 14, 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroevers MJ, Ranchor AV, & Sanderman R (2003). Depressive symptoms in cancer patients compared with people from the general population: The role of sociodemographic and medical factors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 21(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sidell N (1997). Adult adjustment to chronic illness: A review of the literature. Health and Social Work, 22(1), 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AB, Selby PJ, & Velikova G (2002). Factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale from a large cancer population. Psychology Psychotherapy, 75, 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith PR (2003). The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(29). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesauro GM, Rowland JH, & Lustig C (2002). Survivorship resources for post-treatment cancer survivors. Cancer Practice, 10, 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tulder MW, Aaronson NK, & Bruning PF (1994). The quality of life of long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol, 5(2), 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Turner-Bowker DM, Kosinski M, & Gandek B ( 2002). The SF-12v2 Health Survey Users Manual. Lincoln: QualityMetric Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wortman CB, & Dunkel-Schetter C (1979). Interpersonal relationships and Cancer: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 35(1), 120–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yellen SB, Cella DF, & Bonomi A (1993). Quality of life in people with Hodgkin’s disease. Oncology 7, 41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, & Piantadosi S (2001). The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-oncol, 10(1), 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ (2000). Cancer survivor identity and quality of life. Cancer Practice, 8(5), 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Benrnaards CA, Petersen L, & Abraham L (2006). Assessing the impact of cancer: Development of a new instrument for Long-term survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 407–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Mills J, & Weitzman TS (2007). Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 1, 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, & Snaith RP (1983. ). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]