Abstract

Despite the progress in safety and efficacy of cell replacement therapy with pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), the presence of residual undifferentiated stem cells or proliferating neural progenitor cells with rostral identity remains a major challenge. Here we report the generation of a LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 alpha (LMX1A) knock-in GFP reporter human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line that marks the early dopaminergic progenitors during neural differentiation to find reliable membrane protein markers for isolation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Purified GFP positive cells in vitro exhibited expression of mRNA and proteins that characterized and matched the midbrain dopaminergic identity. Further quantitative proteomics analysis of enriched LMX1A+ cells identified several membrane-associated proteins including a polysialylated embryonic form of neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) and contactin 2 (CNTN2), enabling prospective isolation of LMX1A+ progenitor cells. Transplantation of human-PSC-derived purified CNTN2+ progenitors enhanced dopamine release from transplanted cells in the host brain and alleviated Parkinson's disease-related phenotypes in animal models. This study establishes an efficient approach for purification of large numbers of human-PSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors for therapeutic applications.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, Label-free quantification, Spectral counting, Stem cells, Progenitor cells

Midbrain dopaminergic neurons are a subset of the neuromodulatory neurons that reside in the basal ganglia, substantia nigra pars compacta, and ventral tegmentum areas that project axons to the dorsal striatum, prefrontal cortex, and ventral striatum regions, respectively. Loss of the nigrostriatal pathway is a pathological outcome of Parkinson's disease (PD); other pathological hallmarks include aggregation of alpha-synuclein (SNCA) and formation of Lewy bodies in affected neurons. In order to restore the degenerated neurons, fetal mesencephalic cells have been utilized in clinical trials (1, 2). These studies suggest that transplanted cells can survive in the brains of patients with PD and resulted in amelioration of the disease symptoms (3, 4). Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) are another source of human-derived cells for cell replacement therapy in neurodegenerative diseases. There has been considerable progress in increasing survival as well as functional effects of transplanted dopaminergic neurons from PSCs (5–7). Transplantation of neural progenitor cells differentiated from human PSCs to the brain of an animal model of PD have resulted in their long-term survival and correct target innervation comparable to fetal midbrain tissue (8). Despite progress in safety and efficacy of cell therapy with PSCs, major concerns that remain unaddressed include the presence of residual undifferentiated stem cells or proliferating neural progenitor cells with rostral identity, which may cause overgrowth and tumor formation (8–12). Contamination with serotonergic neurons could lead to graft-induced dyskinesia following the transplantation of cells in the host brain (13–16). Various protocols and different batches of differentiated cells generated from the same protocol have shown biochemical differences, which leads to variability in transplantation outcomes. Therefore, standardized protocols to isolate and purify cells for transplantation are essential for consistent and reliable results.

Here we report the generation of a LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 alpha (LMX1A) knock-in a GFP reporter human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line that marks the early dopaminergic progenitors during neural differentiation. This reporter cell line was differentiated toward dopaminergic neurons followed by enrichment of GFP-positive cells in vitro. Purified cells exhibited expression of mRNA and proteins that characterized and matched the midbrain dopaminergic molecular signature. Differentiation of purified cells yielded a homogeneous population of dopaminergic neurons with functional properties that expressed marker genes. Comparative shotgun proteomics analysis revealed the presence of a specific protein expression pattern in dopaminergic progenitors and mature neurons. The combination of Western blotting and immunostaining approaches confirmed the results. Enrichment of membrane proteins in the purified cell population was a criterion to monitor dopaminergic progenitor cell purification.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Human Embryonic Stem Cell (hESC) Culture and Construction of the Knock-in LMX1A Cell Line

hESC Royan H6 (passages 25–35) (17) and H9 (WiCell) cells were maintained under feeder-free conditions on Matrigel (17). The medium was changed daily and cells passaged once weekly with collagenase/dispase at a ratio of 1:2 (R&D Systems). hESCs showed the normal karyotype (46XY) and expressed the key pluripotency markers, Oct4 and Nanog.

The pKO-DTA backbone (a gift from the Eccles Institute of Neuroscience, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Australian National University) was used to construct the targeting vector. Right and left homology arms were amplified from Royan H6 genomic DNA as a template with the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). We removed the ATG start codon from the end of the left arm and added one nucleotide to the start of the right arm. The right homology arm replaced the KpnI and XhoI sites in the vector. Then, eGFP was inserted into the NotI and SacII sites, and we cloned the left arm in the NotI site. Genomic PCR products and constructed clones were sequenced for possible errors in the PCR amplification process. We selected clones with no mismatch against NCBI human reference genome GRCh37.p13 Primary Assembly for electroporation. The final vector (12,451 bp) comprised of a 3,388-bp 5′ homology arm, eGFP, loxp flanked by Neo resistance cassette, and a 2,824-bp 3′ homology arm, which was introduced into the hESCs.

Genetic modification and electroporation were performed as previously reported (18). Briefly, feeder-free hESCs were dissociated into single cells with Accutase for 10 min at 37 °C. A total of 10 × 106 cells per 700 μl of cold PBS were incubated with 20 μg of linearized plasmid in the BlcI site for 5 min on ice. Cells were electroporated in 0.4-cm cuvettes (Gene Pulser Xcell modular electroporation system, Bio-Rad) with 250-V and 500-μF constant parameters, after which cells were harvested by centrifugation and replated on mitomycinated MTK-Neo media (Australian National University). G418 (Sigma) selection was started after three days and continued for a period of 10 days (range: 50–200 μg/ml). To excise the neomycin cassette, we electroporated the cells with CRE recombinase plasmid transiently as described above. Targeted clones were identified by long PCR amplification from outside of the targeted region, and we kept the modified colonies for karyotype and differentiation analysis. We used the qPCR and reference controls as previously described (19) for copy number quantification in order to eliminate any random integration events in the established clones.

Cell Differentiation

Neural differentiation of the cultured cells was achieved as previously described (5). Briefly, feeder-free hESCs (Royan-H6 and H9) colonies were detached as cell patches by 1:2 ratio of collagenase/dispase. Embryoid bodies were formed in ROCKi (Y27632, 10 μm) (after two days) that contained a 1:1 ratio of DMEM/F12:neurobasal (21103_ 049; Gibco) medium supplemented with 1% N2 (17502_048; Gibco), 2% B27 (17504_044; Gibco) supplement without vitamin A, StemoleculeTM SB431542 (10 μm), StemoleculeTM LDN-193189 (100 nm), StemoleculeTM CHIR99201 (0.7 μm), and 200 ng/ml SHH (R&D Systems). Medium of the differentiated cells was changed a day after initial seeding. On day 4, embryoid bodies were plated onto the dishes coated with laminin (5 mg/ml; L2020; Sigma) and poly-l-ornithine (15 mg/ml; P4957; Sigma). N2 and B27 supplement concentrations were reduced to one-half, and we completely excluded SB431542 from the media by day 10. On day 12 of differentiation, cells were dissociated by 0.008% trypsin (27250_018; Gibco) and 2 mm disodium EDTA (108454; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Single cells were replated on laminin and poly-l-ornithine-coated tissue culture dishes and differentiated for a further two weeks in neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27, 2.5% KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR), 200 mm ascorbic acid (A8960; Sigma), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; 20 ng/ml; 248 BD/CF; R&D), glial-derived neurotrophic factor (20 ng/ml; G1777; Sigma), and db-cAMP (1 ng/ml; D0260; Sigma). For rostral forebrain differentiation, day 2, H9 hESCs cultures (from WiCell®) were treated with the basic differentiation media similar to that for dopaminergic neurons, supplemented with StemoleculeTM SB431542 (10 μm), and StemoleculeTM LDN-193189 (100 nm) for one week, and then cells were treated with dispase and replated in the differentiation medium with FGF2 (10 ng/ml) and Cyclopamin (2 μm) for another one week. The cells were then lifted mechanically and allowed to form a sphere in the suspension culture for a week. For caudal spinal progenitor differentiation, we used the same protocol as for dopaminergic (DA) neurons except that we added retinoic acid (RA) (1 μm) and 3 μm StemoleculeTM CHIR99201 for the first two weeks and cells were lifted mechanically and cultured as suspension in basic differentiation medium containing RA (1 μm) and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) (100 ng/ml). For cell sorting and analysis, cultures at day 12 (for isolation of CNTN2+ cells) and day 21 (for isolation of NCAM+ cells) were treated with Accutase® (STEMCELL Technologies) for 10 min in room temperature (RT) and cells harvested and washed with PBS two times and then resuspended in the cold sorting buffer (contains PBS, 25 mm HEPES, pH 7, 1% FBS, 5U/ml DNaseI) at a density of 5 × 106 and sorted with BD FACSAria™ III into positive and negative cell populations based on the gating on the software. Sorted cells were recovered before imaging by culturing for 24 h in the differentiation medium. For transplantation, cells were pelleted and resuspended in the cold sorting buffer without further culturing at a density of 7 × 104 cells and maintained on the ice until transplantation.

Immunofluorescence Staining

For immunostaining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, P6148) for 20 min, after which their membranes were permeabilized by 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, T8532) and blocked with 10% host serum of the secondary antibody and 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, A3311). Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies (Table S1) diluted in blocking solution. After three washes, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (Table S1). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, D8417) and analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX71) and Nikon A1 confocal laser microscope system.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TrizolTM reagent (Invitrogen) from three independent biological replicates of cultured cells. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of DNase I (Takara, 2270A)-treated RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentase, KI632) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was carried out on a Rotor Gene 6000 (Corbett Research) in 10 μl reactions that contained 5 μl of SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara, RR041) with 0.375 μm of each primer and each sample run in duplicates for technical replicates. All primers used in these assays were tested for specificity and amplification efficiency (Table S2).

Protein Extraction and Separation by SDS-PAGE

Three replicates from hESC and differentiated samples (at least 5 × 106 cells/sample) were used in the shotgun proteomics. Samples were washed twice with 5 ml ice-cold PBS. The samples were then centrifuged at 450 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Next, we added 1 ml of the lysis buffer (Qiagen) that contained 1 unit of benzonase nuclease and 10 μl of protease inhibitor (100x) to the cell precipitates, which were subsequently incubated at 4 °C. Cells were disrupted by subjecting them to sonication (three times) on ice, each for 5 min (45-s pulses with 15-s intervals). The insoluble debris was then pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was quantified by the Bradford Assay Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) using BSA as the standard. We treated the extracted proteins with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (160 μg per well). Proteins were separated on 12% bis-tris polyacrylamide gels at 100 V for 1 h and visualized using colloidal Coomassie blue. Finally, the gels were washed twice in water (10 min per wash), and the individual lanes were then cut into 12 slices of equal size from top to bottom.

In-gel Digestion by Trypsin

Each stained gel lane was cut into 16 pieces. Each piece was cut again and diced into smaller pieces then placed into individual wells of a 96-well plate. For destaining, the gel pieces were first briefly washed with 100 mm NH4HCO3, followed by washing twice with 200 μl of 50% acetonitrile (ACN)/100 mm of 50% NH4HCO3 for 20 min each time. The pieces were dehydrated with 100% ACN, air dried, and reduced with 50 μl of 10 mm DTT/NH4HCO3 (50 mm) at 37 °C for 1 h. Finally, the samples were alkylated in the dark with 50 μl of 50 mm iodoacetamide/50 mm NH4HCO3 at room temperature for 1 h. Next, samples were briefly washed with 100 mm NH4HCO3 and 200 μl of 50% ACN/100 mm of 50% NH4HCO3 for 10 min, dehydrated with 100% ACN, and air dried. Finally, samples were digested with 20 μl of trypsin (12.5 ng/μl of trypsin in 50 mm NH4HCO3) on ice for 30 min then left overnight at 37 °C. Peptide extractions were carried out for three times with 30 μl of 50% ACN/2% formic acid. Extracted peptides were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and reconstituted into 10 μl with 2% formic acid.

Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The resultant peptides from the SDS-PAGE gel slices were analyzed by nanoflow liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS/MS) using an LTQ-XL ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo, Fremont, CA, USA). Reversed-phase columns were packed in-house to ∼9 cm (100 μm inner diameters) using 100 Å, 5 μm Zorbax C18 resin (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and 5 μm Zorbax C18 resin (Agilent Technologies Santa Clara, CA, USA) in a fused silica capillary with an integrated electrospray tip. A 1.8-kV electrospray voltage was applied via a liquid junction upstream of the C18 column. Samples were then injected into the C18 column using a Surveyor autosampler (Thermo, Fremont, CA, USA). The column was washed with buffer A that consisted of 5% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid for 10 min at 1 μl/min before each loading. The peptide elution was carried out with 0–50% buffer B that consisted of 95% v/v ACN and 0.1% v/v formic acid over 58 min at 500 nL min−1 followed by 50–95% buffer B over 5 min at 500 nl min−1. The eluted peptides were then directed into a nanospray ionization source of the mass spectrometer. Spectra were scanned over the range of 400–1,500 amu. Automated peak recognition, dynamic exclusion window set to 90s, and tandem MS of the top six most intense precursor ions at 35% normalization collision energy were performed using Xcalibur software (version 2.06; Thermo, Fremont, CA, USA).

Protein Identification

Raw files were converted to the mzXML format using the ReAdW program and processed through Global Proteome Machine software with version 2.1.1 of the X!Tandem algorithm (available in the public domain at: http://www.thegpm.org). For each experiment, 16 fractions were processed sequentially with output files for each individual fraction, and we generated a merged, nonredundant output file for protein identification with log (e) values less than −1. Tandem mass spectra were searched against Homo sapiens protein database compiled from NCBI (Refseq protein database containing 99,871 sequences as of September 2014) with the search parameters that included MS and MS/MS tolerances ±2 Da or ±0.2 Da and K/R-P cleavages and allowed for up to two missed tryptic cleavages. The database contained a list of common human tryptic peptide contaminants. Fixed modifications were set for carbamidomethylation of cysteine and variable modifications were set for methionine oxidation.

Functional Annotation

The gene identifier (GI) numbers of proteins were converted to Symbols and Entrez accession IDs using the bioDBnet biological database network (20). The lists of up- and downregulated proteins with relative GI ID for each comparison were then uploaded in DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins (10 μg total) from hESCs, LMX1a-positive and -negative progenitors were electrophoresed in 12% SDS-PAGE (120 V for 1 h) using a Mini-PROTEAN 3 electrophoresis unit (Bio-Rad). The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Amersham Biosciences) by semi-dry blotting (Bio-Rad) using Dunn carbonate transfer buffer (10 mm NaCHO3, 3 mm Na2CO3, 20% methanol). Membranes were blocked for 1.5 h using western blocker solution (Sigma, W0138) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Table S8). Membranes were incubated with the peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit IgG (1: 100,000, Sigma, A2074) as appropriate for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the blots were visualized using ECL detection reagent (Sigma, CPS-1–120) and images were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

Cell Transplantation and Behavior Analysis

All animal procedures received the approval of the Royan Institutional Review Board and Institutional Ethical Committee (approval ID: J/90/1397). For the in vivo transplantation studies, we used adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g). Animals were obtained from Razi Institute (Karaj, Iran) and maintained in temperature-controlled rooms with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle, 50–55% humidity, and ad libitum access to food and water. The nigrostriatal dopamine pathway was partially lesioned in the host rats by an injection of 4 μl 6-hydroxydopamine (3.5 μg/μl free base dissolved in a solution of 0.2 mg/ml l-ascorbic acid in 0.9% w/v NaCl) into the medial forebrain bundle at the following coordinates with reference to the bregma and dura: anterior/posterior (AP): −4.4 mm; medial/lateral (ML): −1.2 mm; and dorsal/ventral (DV): −7.8 mm; target base (TB): −2.4). After three weeks, we assessed the effect of the lesion on motor function according to assessment of motor impairments, implementing tests that examine for a side bias. We used an apomorphine-induced rotation test, apomorphine (subcutaneous (s.c.) at a dose of 0.25 mg/kg) was injected, and contralateral turns were monitored for a period of 40 min using automated rotameter. For spontaneous motor tests, we examined forelimb use during explorative activity; briefly rats were placed individually in glass cylinder, and the number of independent wall placements observed for the right forelimb, left forelimb, and both forelimbs simultaneously were recorded for 10-min periods. Lesioned animals were stratified across four groups (n = 8 per group) according to values obtained for both the behavioral measures. Only rats that exhibited a mean net rotation of at least six full turns/min for apomorphine over 60 min and ≤25% use of the forelimb contralateral to the lesion in the cylinder test were included in the study.

One week after the behavioral pretesting (four weeks after lesioning), each animal received a total amount of 2 μl of CNTN2+ cells and 4 μl of NCAM+ cells of cell suspension that contained the same cell numbers for unsorted cells, NCAM+ and CNTN2+ cells, and fibroblast cells. We adjusted the cell numbers to 70,000–80,000 cells/μl. Two separate deposits of 1 μl each were placed along each of two implantation tracts in the head of the striatum at the following coordinates with reference to the bregma and dura: AP: +1.2/+0.5 mm; ML: −2.6/−3 mm; DV: −4.5 mm; and TB: −2.4 mm). The capillary was left in place 5 min before withdrawal. The animals survived for 10–12 weeks, during which we analyzed their motor performance behavior every two weeks. Immunosuppressive treatment in the form of daily intraperitoneal injections of cyclosporine A (Novartis; 10 mg/kg,) was administered throughout the experiment, beginning the day prior to transplantation.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

For statistical comparisons, we used three independent differentiations from Royan H6 (P25–35) and H9 to dopaminergic progenitors (n = 3), dorsal forebrain (n = 3), spinal progenitors (n = 3), and dopaminergic mature neurons (n = 3). For qPCR comparisons, we ran two technical replicates along with our biological replicates to minimize the variation in each run. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the comparative CT method (Delta Delta CT method) with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) used as an internal control for normalization in REST © (Relative Expression Software Tool). Cell quantification for immunostaining images was performed using ImageJ and cell counter plugin for over 1,000 cells.

The p value and the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) were used to determine the significance of enrichment or overrepresentation of terms for each annotation [e.g. Gene Ontology biological process and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway]. These proteins were also selected and reloaded into Qiagen Ingenuity R Pathway Analysis (IPAR, Qiagen, CA, USA, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) for further analysis using gene symbols as identifiers, along with fold changes and adjusted p values as observations with a cutoff of 35 molecules per network and 25 networks per analysis. For Gene Ontology categories of interest, normalized spectral abundance factors (NSAF) abundance data were summed to achieve the overall protein abundance change over time for biological process categories. Then, Gene Ontology annotation and relative protein abundance were plotted side by side for the up- and downregulated proteins for each of the comparison tests.

Quantitative MS analysis was performed on three biological replicates of hESCs, LMX1a-positive and -negative progenitor cells and their corresponding differentiated neurons. For each condition, we combined the Global Proteome Machine outputs from each of the three biological replicates to produce a single nonredundant/high-confidence shotgun proteomic analysis output. The final list contained only the proteins that are identified in all three biological replicates of at least one condition, with a minimum summed spectral count across three replicates of five. FDRs of identification were calculated using a reversed sequence decoy database: Protein FDR = (#reverse proteins identified)/(total protein identifications) × 100 and Peptide FDR = 2 × (#reverse peptide identifications)/(total peptide identifications) × 100 (21, 22). We used NSAF as previously described by Zybailov et al. (2007) to estimate protein abundance data (23) For each protein k in sample i, the number of spectral counts that identified the protein were divided by the estimated protein length. The protein length was determined by dividing the molecular weight of the protein by the average amino acid molecular weight. SpCk/Length values were normalized to the total by dividing by the sum (SpCk/Lengthk) over all proteins, which yielded NSAFi values for each sample i. When plotting or summarizing the overall protein abundance for a particular condition, we used the average of the NSAF values for all replicates as a measure of protein abundance. A spectral fraction of 0.5 was initially added to all spectral counts to compensate for null values and allow for log transformation of the NSAF data prior to statistical analysis (24).

Student's t-tests on log-transformed NSAF data were used to determine differentially accumulated proteins for each comparison tests. Proteins with t test p values <0.05 were considered to be significantly changed between the two conditions. Additionally, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also performed to identify proteins that changed in abundance among those proteins and were present and reproducible under all conditions. The analysis was performed on log-transformed NSAF data, and proteins with an ANOVA p value <0.05 were considered to show a significant change between the different experimental conditions.

RESULTS

Characterization and in Vitro Differentiation of LMX1A-GFP Reporter Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs)

We generated LMX1A-GFP knock-in cell line (Fig. 1B) by using electroporation to introduce linearized pKO-LA-GFP-RA-DTA constructs (Table S2, Fig. S1) into hESCs. Cells were subjected to antibiotic treatment with G418, and the resultant antibiotic resistant hESC clones were screened by PCR genotyping primer pairs specific to the desired targeted allele (Fig. S1). DNA sequencing further revealed that the flanking sequences of homology arm regions were identical to the predicted targeted allele in the two knock-in clones. qPCR-based assay results further indicated that only one copy of the GFP gene existed in each of the knock-in cell lines (Fig. S1B), which reflected the absence of randomly integrated copies of the donor vector.

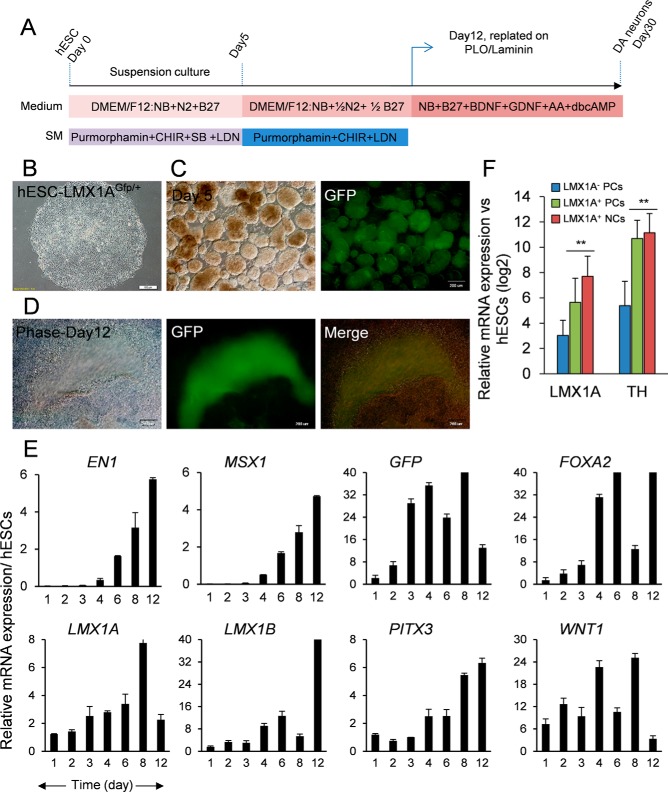

Fig. 1.

Establishment, characterization, and differentiation of LMX1AGFP/+ hESCs. (A) Schematic view of the medium ingredients. (B) Morphology of hESC colony in the feeder-free culture and (C) embryoid bodies on day 5 of differentiation before plating where cells expressed the GFP reporter. (D) Phase image of day 12 progenitors after plating with highlighted cells that expressed GFP. (E) Time course qPCR data for some of the developmentally important genes during the first days of differentiation. (F) qPCR comparison among LMX1A-negative progenitors, positive progenitors, and differentiated neurons versus hESCs for LMX1B and TH transcripts. DA: dopaminergic neurons; SB: SB431542; LDN: LDN-193189; GDNF: glial-derived neurotrophic factor; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; AA: ascorbic acid; dbcAMP: dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

LMX1A-GFP clones (Fig. 1B) differentiated into the dopaminergic neurons with the floor plate based midbrain DA neuron protocol (Fig. 1A) and depicted the reporter expression five days postdifferentiation (Fig. 1C) and maintained its expression throughout the differentiation time until day 12 (Fig. 1D). Gene expression analysis of mRNA levels revealed a higher expression of genes associated with DA progenitor cells 8–12 days after induction, with the maximum expression of the reporter gene at day 8 (Fig. 1E). Cells isolated by FACS (Fig. S2A) were analyzed by qRT-PCR to confirm enrichment for expression of DA-specific transcripts compared with the negative control population. Our results demonstrated 32-fold enrichment for LMX1B and 64-fold enrichment for TH expression in the GFP reporter cells compared with the negative cells (Fig. 1F).

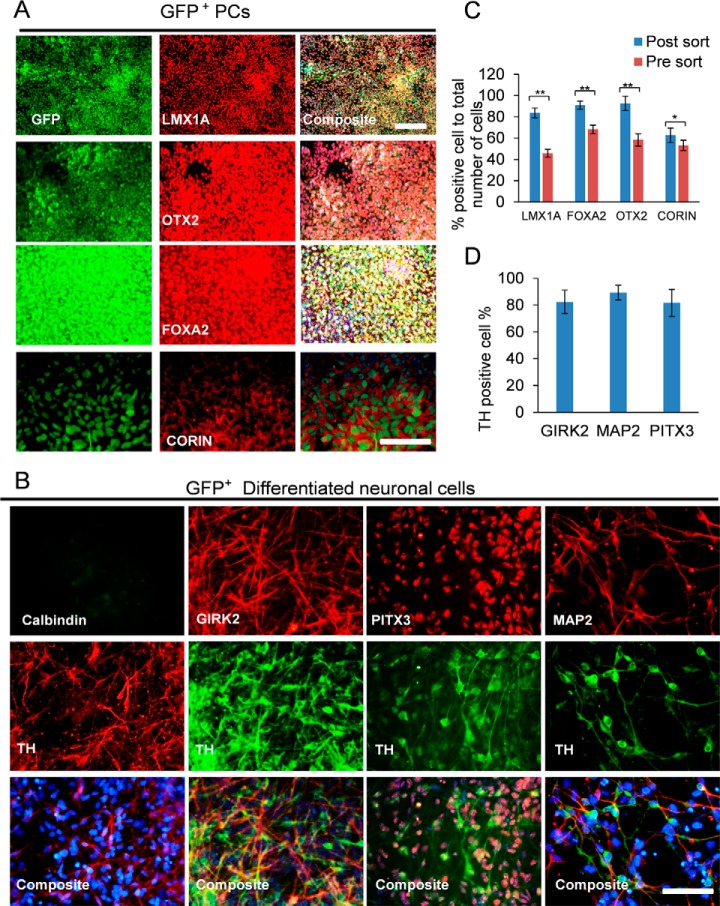

Immunostaining analysis of FACS-sorted cells confirmed that a large extent of the cells that expressed GFP also co-expressed FOXA2 (91%±3.9), LMX1A (84%±4.7), OTX2 (93%±5.3), and CORIN (63%±6.7) proteins 24 h after sorting (Fig. 2A and 2C, Fig. S2C). Further differentiation of the GFP-positive cells resulted in significant elongation of the axons and improved arborization (Fig. 2B). We observed that TH expression co-localized with GRIK2 (82%±8.7), PITX3 (82%±10), and MAP2 immunoreactivity (89%±5.4; Fig. 2D, Fig. S2). Together, these in vitro data supported our hypothesis that the knock-in approach could be effectively used to purify a progenitor population of midbrain DA neurons.

Fig. 2.

In vitro characterization of GFP+ DA progenitors. (A) Immunostaining for putative DA progenitor proteins LMX1A, FOXA2, OTX2, and CORIN at day 12 progenitors after cell sorting. (B) Differentiated neurons on day 30 from GFP-positive cells co-stained for TH and CALB2, GIRK2, PITX3, and MAP2. Quantification of immunostaining results for percentage of the (C) progenitors (n = 3 independent experiments; mean ± S.D.; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; Dunnett's test) and (D) mature neurons that expressed the DA markers. In all experiments, the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (Scale bars = 50 μm).

Proteome Signature Analysis of LMX1A-GFP hESCs and Differentiated Cells Enabled Identification of DA-neuron-enriched Proteins

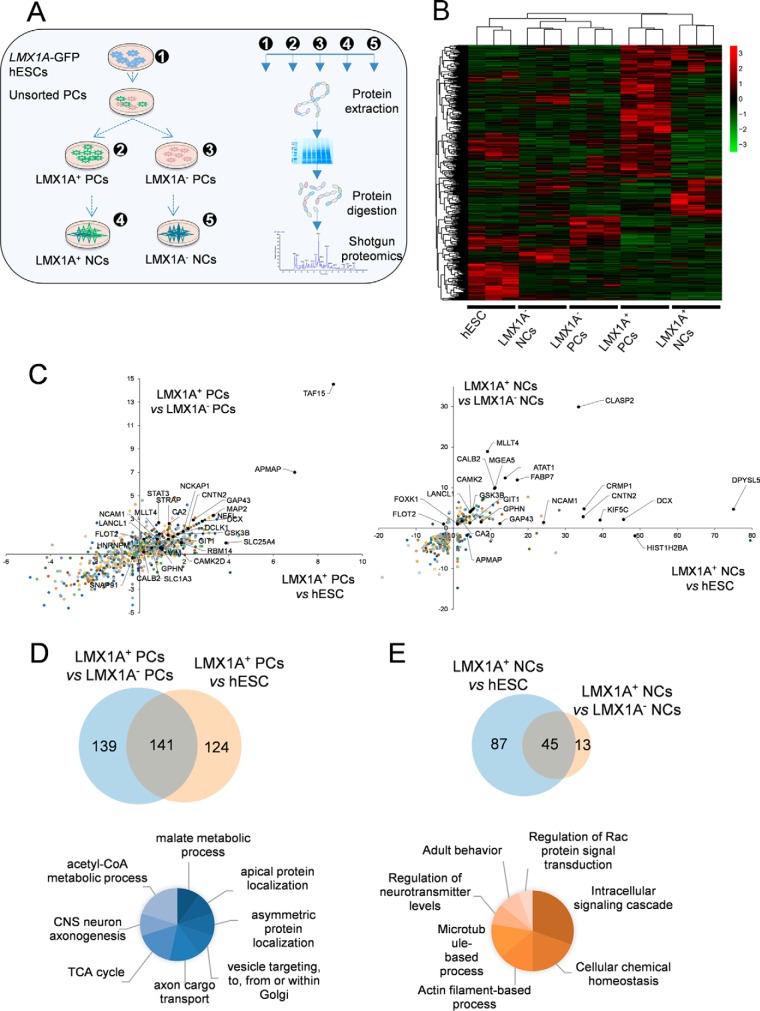

We performed shotgun proteomics analysis of FACS-purified cells for DA progenitors and mature neurons at days 12 and 30, respectively and for the negative population for both progenitors and mature neurons (n = 3 independent differentiation for each step) (Fig. 3A). Supplemental Table S3 lists all raw data for the identified proteins in each sample, protein and peptide FDR, and all identified proteins. Overall, across all analyzed samples, we reproducibly identified 1,572 proteins with a protein and peptide FDR of less than a 1% threshold (Table S4). The data were considered as highly stringent and required no further filtering. The expression of 906 proteins demonstrated significant alterations among all samples, which were plotted in the heat map (Fig. 3B, Table S5). We assessed the dopaminergic progenitor cells and mature neuron-specific proteome profiles by comparing reporter-positive cells against hESCs and negative control cells. The protein fold changes were calculated and plotted as in the scatter graphs for the progenitor cells and neurons (Fig. 3C). Our results showed that 280 identified proteins were overrepresented in the LMX1A-positive progenitors (expression ratio ≥ 2 and p ≥ 0.05) compared with the negative control cells. There were 141 proteins that expressed mainly in the GFP-positive progenitors related to the stem cells. However, 139 proteins were highly expressed in positive progenitors that might have some expression in the hESCs (Fig. 3D; also see Fig. S3). Additionally, 124 proteins were exclusively expressed in the positive progenitors related to the hESCs and might have expression in negative cells (Table S6). In the differentiated LMX1A-positive neurons, 132 proteins had increased expression compared with hESC samples, whereas 58 proteins had increased expression compared with the LMX1A-negative neurons (Fig. 3E, Table S6). Up-regulated proteins identified in the LMX1A-positive progenitors are mainly involved in malate metabolism, apical protein localization, asymmetric protein localization, and vesicle targeting to, from, or within the Golgi, and axonal cargo transport. In addition, these proteins have also been implicated in biochemical pathways associated with neural differentiation processes such as TCA cycle and acetyl-CoA metabolism (Fig. 3E, Table S7). The biological processes that were mainly overrepresented in the LMX1A-positive neurons primarily associate with intracellular signaling cascades involved in Rac signaling, intracellular biochemical homeostasis, actin filament and microtubule formation, regulation of neurotransmitter release, and adult behavior (Fig. 3D and 3E).

Fig. 3.

Expression pattern for differentially expressed proteins during DA differentiation in GFP-positive and -negative cells. (A) Schematic representation of proteomics workflow and samples analyzed in this study. (B) Hierarchical clustering based on expression correlations between 906 differentially expressed proteins depicted as heatmap for three replicates of different samples. (C) Scatter plot visualization for expression ratio of proteins in LMX1A+ progenitors (left) and LMX1A+ neurons (right) compared with LMX1A− cells and hESCs. (D) Up-regulated proteins in the LMX1A+ progenitors compared with LMX1A− cells and hESCs. Corresponding biological processes for proteins enriched in the positive cells versus negative progenitors. (E) Up-regulated proteins in LMX1A+ neurons compared with LMX1A− neurons and hESCs. Corresponding biological processes for proteins enriched in the positive differentiated neurons versus the LMX1A− neurons.

Validation of Differentially Expressed Proteins

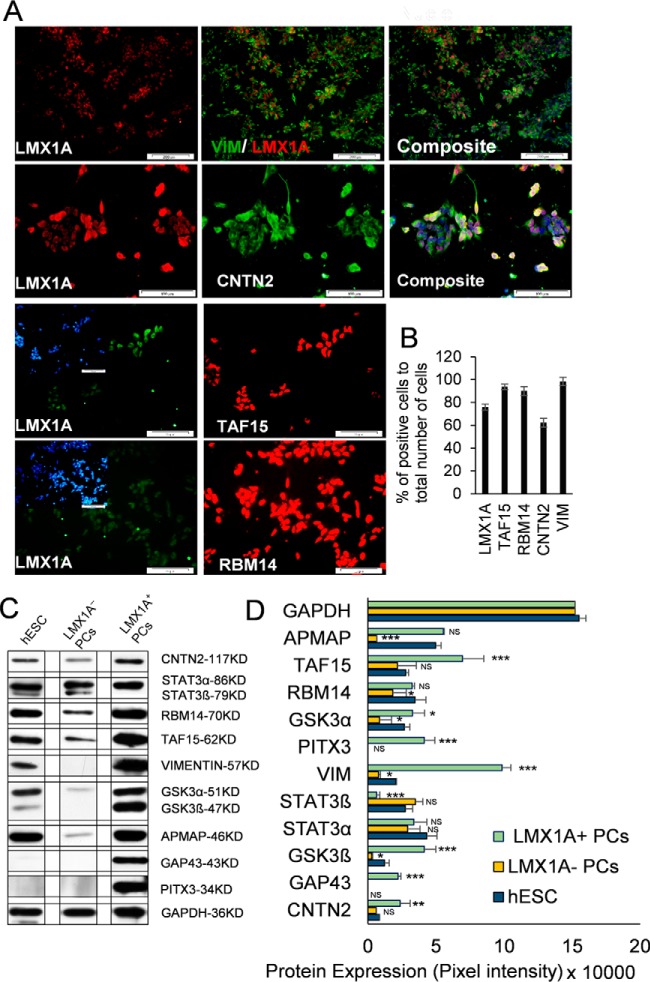

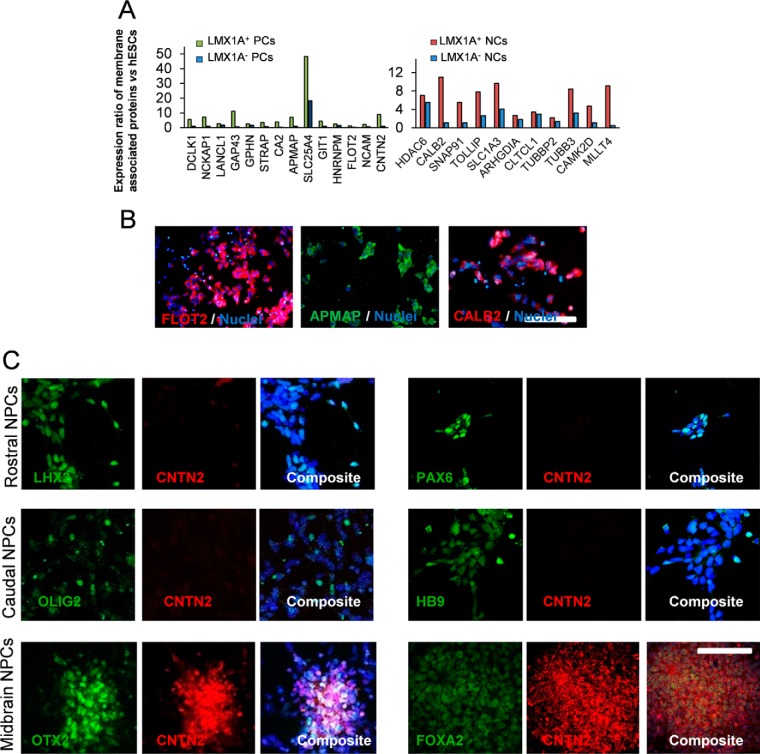

To corroborate the results obtained by the MS analysis, we subjected selected proteins to immunostaining and Western blot analysis. We sought to verify the abundance and localization of up-regulated proteins and their co-expressions with the LMX1A protein as a hallmark of progenitor cells. Immunostaining results for RBM14 and TAF15 (nuclear proteins), VIM (cytoplasmic protein), and CNTN2 (membrane-associated protein) confirmed that all assessed proteins co-expressed with LMX1A-positive cells in the unsorted population of progenitors (Fig. 4A and 4B). Western blotting analyses of hESCs, positive LMX1A cells, and negative control cell lysates revealed changes that matched the results obtained from the MS analysis (Figs. 4C and 4D, Fig. S6). Specifically, we observed two isoforms of STAT3 protein in the hESC and negative control cells, while the positive cells expressed only the longer alpha isoform. Similarly, positive cells demonstrated much greater protein expressions for RBM14, TAF15, VIM, GSK3β, APMAP, GAP43, PITX3, and CNTN2 proteins in LMX1A-positive cells compared with the LMX1A-negative cells (Fig. 4D). Although, we observed detectable expressions of these proteins in the negative and hESCs; GAP43, GSK3β, and VIM were robustly expressed in the positive progenitor cells. We also investigated the localization of some of the identified proteins for possible cell surface association that could potentially serve as a suitable marker for DA progenitor cells (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescence staining followed by microscopic examination confirmed cell surface localization for CNTN2, FLOT2, CALB2 (caltretinin), and APMAP proteins in the progenitor cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Expression of several identified proteins in the LMX1A+ progenitors. (A) Immunostaining for LMX1A as a DA-progenitor-specific protein, TAF15 and RBM14 transcription factors (the blue channel shown inside the green channel is the total nuclei for the cells), and its co-expression with vimentin and contactin 2 proteins. (B) Quantification results of immunostaining for images in panel (A). (C) Representative band images of multiple Western blot analysis (n = 3/group) (Fig. S6) are presented. One replicate of each group from similar blot has been presented for newly identified proteins in the human embryonic stem cell (hESCs), LMX1A+ and LMX1A− progenitors at day 12 after differentiation, and (D) quantification of band intensity for each protein in three replicates of samples normalized with GAPDH protein expression and mean expression of each group compared with the expression of proteins in the hESCs. PITX3 protein was used as a positive control (n = 3 independent experiments; mean ± S.D.; NS: not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Dunnett's test).

Fig. 5.

Expression of identified membrane associated proteins in the LMX1A+ progenitors and neurons. (A) Expression of membrane proteins based on the cellular component analysis in the LMX1A+ progenitors and neurons compared with the LMX1A− progenitors and neurons normalized with their expression in the hESCs. (B) Membrane localization of flotillin 2, APMAP1, and calbindin 2 proteins at day 12 after differentiation in unsorted progenitors. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (C) Evaluation of CNTN2 expression in the H9-derived rostral forebrain progenitors expressing LHX2 and PAX6, caudal spinal progenitors expressing OLIG2 and HB9, and midbrain progenitor cells expressing OTX2 and FOXA2. (Scale bars = 50 μm).

Isolation of DA Progenitors Based on the Cell Surface Proteins and Transplantation into the PD Animal Model

For further illumination of the specificity of our differentiation method and its validation by the proteomics approach, we differentiated H9 hES cell line to the rostral and caudal neural progenitors (see the methods) and examined the expression of CNTN2 as one of the specific proteins that we found has a higher expression in DA progenitors. We found that both forebrain progenitors expressing LHX2 and PAX6 and caudal spinal neural progenitors expressing OLIG2 and HB9 had little expression of CNTN2, but the midbrain progenitors developed by our protocol had higher and specific expression determined by double staining with FOXA2 and OTX2 (Fig. 5C). We decided to isolate the progenitor cells based on their membrane protein expression. We tested flotilin, calretinin, NCAM, and APMAP antibodies and three different antibodies for CNTN2. Most of commercial antibodies available for these proteins did not have enough specificity for the FACS system and failed to generate reliable results (the consistency that we defined here was as a coefficient of variation less than 25%), except for one CNTN2 antibody (Abcam, ab133498) and NCAM antibody (Figs. S4 and S5). Antibodies against these proteins depicted acceptable consistency for purifying progenitors from the mixed culture of progenitors. Immunostaining for pluripotency markers OCT3/4 and NANOG in day 12 progenitors sorted with CNTN2 and unsorted showed that these cells retained OCT3/4 expression at a lower level, but both populations were negative for NANOG expression, indicating elimination of residual undifferentiated embryonic stem cells during the differentiation process (Fig. S2).

Temporal analysis of CD24 (cell marker for early neural progenitors) and CD56 (NCAM) protein expressions with FACS indicated that, over differentiation time for the population of CD24+ cells decreased from 84% at day 9 to 18% at day 21, and population of NCAM-positive cells increased gradually from 14% at day 9 to 84% at day 21 (Fig. S5A), consistent with proteomics data. CD56-positive cells were isolated from the culture at day 21 of differentiation and transplanted into the striatum of adult rats pretreated unilaterally with 6-OHDA. Animals receiving CD56+ sorted cells (n = 15) were compared with intact control animals (n = 15) and lesioned animals without cell administration (n = 10). All animals received daily cyclosporine treatment for immunosuppression and minimized tissue rejection until rats were euthanized at the end of week 12. Animals grafted with CD56+ cells showed significant recovery in rotation behavior 6–12 weeks after implantation, and only in this group there was a significant improvement in contralateral forelimb use over the lesion control animals at the 8–12 week time points. (ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test; p ≤ 0.01; Fig. S5B).

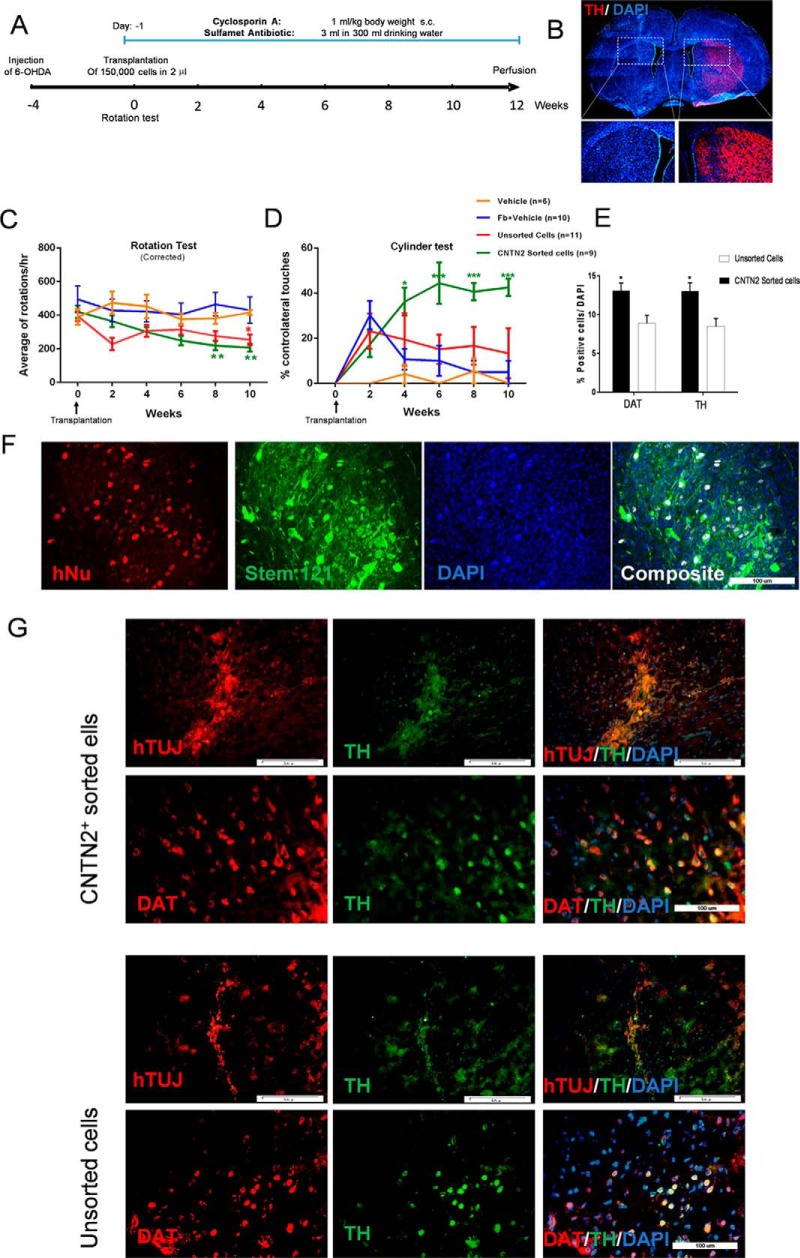

We also surgically transplanted CNTN2-positive cells isolated from the culture after 12 days of differentiation into the striatum of adult rats pretreated unilaterally with 6-OHDA (Fig. 6A and 6B). The animal groups were separately transplanted with differentiated hESCs using three different cell types: CNTN2 sorted cells (n = 15), total unsorted cells (n = 15), control fibroblast cells (n = 10), and vehicle group without cells (n = 10). All animals received daily cyclosporine treatment for immunosuppression and minimized tissue rejection until rats were euthanized at the end of week 12.

Fig. 6.

Transplantation of CNTN2+ cells to the striatum of the PD animal model. (A) Schematic view of PD animal model, treatments, and timing in CNTN2+ cell replacement strategy. (B) Immunohistochemistry analysis of 6-OH dopamine semi-lesioned rat brain at four weeks after lesion for TH to mark DA neuron terminals in the striatum. (C) Normalized apomorphine-induced rotation at 10 weeks after transplantation in vehicle and animals transplanted with CNTN2+ cells, unsorted cells, and fibroblast cells; rats in the vehicle and grafts of fibroblast cells showed no reduction in drug-induced rotations at any of the analyzed time points. (D) CNTN2+ grafted animals displayed significantly more paw touches than lesion control rats and unsorted cells when tested in the cylinder at four weeks after transplantation and afterward. The animals that received unsorted cells showed no significant difference with the control animals. (E) Quantification of the numbers of TH+ and DAT+ cells in the transplanted CNTN2+ sorted versus unsorted cells in the grafted region of PD animals. (F) Immunohistochemistry analysis of the grafted region with human-specific nuclei (hNu) and human-specific cytoplasmic marker (stem 121) and (G) immunohistochemistry for human-specific TUJ1, TH, and DAT antibodies for engrafted human cells in the rat brain. Both CNTN2+ sorted cells and unsorted cells were positive for TH and DAT immunostaining. All data are presented as mean ± S.E. *p < 0.01 (CNTN2+ sorted cells versus unsorted cells), **p < 0.001 (CNTN2+ sorted cells versus unsorted cells and lesion control), ***p < 0.0001 (CNTN2+ sorted cells versus unsorted cells and lesion control).

Animals grafted with both sorted and unsorted progenitors showed significant recovery in their rotational behavior test at 10 weeks after cell transplantation as well as dopamine release caused by reversed apomorphine-induced rotational asymmetry in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats (ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test; p ≤ 0.01; Fig. 6C). However, we observed faster recovery, at the end of eight weeks, in the animals that received the sorted cells (Fig. 6C). We observed significant improvement in contralateral forelimb akinesia over the lesion control for CNTN2-sorted progenitors that was significantly more when compared with the unsorted population (Fig. 6D). Histological analysis of brain sections revealed that all grafted animals, except those implanted with fibroblast cells, had transplants that survived and stained positive for human-specific proteins (Fig. 6F). None of the grafts showed signs of any tumor formation or cell overgrowth. There was a significant differentiation of transplanted progenitors in both sorted and unsorted cells in the TH- and DAT-positive neurons. There were also a significant number of CNTN2-positive progenitors that expressed TH and DAT proteins compared with the unsorted cells (Fig. 6E and 6G).

DISCUSSION

Transgenic human PSCs, as a potential therapeutic platform, are being increasingly explored in order to obtain an enriched population of differentiated cells in vitro (25–27). Among various transgenesis methods, the knock-in approach to introduce reporter genes in cell lines holds the promise of precise gene expression with minimal positional effects or disruption of other genes caused by random integration. We used the LMX1A locus as a crucial transcription factor to develop mesodiencephalic dopaminergic neurons (28) to mark the early stage of DA progenitor development and characterize proteins that are exclusively expressed in these cells. Overexpression of LMX1A in the human pluripotent cells increased differentiation of these cells to the DA neurons (29), and we previously reported that addition of TAT-permeable LMX1A recombinant protein in differentiation culture increased hESCs-derived differentiated DA neurons (7). The transgenic heterozygous cells prepared in this study had normal growth and karyotyped as normal hESCs and successfully differentiated to DA neurons. The LMX1A gene had decreased expression; therefore, we detected reporter expression using immunostaining approaches during initial days of differentiation (starting from day 3), which reached the maximum expression by day 8 after induction. These observations substantiated previous reports and were consistent with other studies that elucidated LMX1A expression during embryonic development and human PSC differentiation (30–32). The cells that were positive for GFP expression mainly expressed floor plate proteins FOXA2 and CORIN and dopaminergic-specific protein PITX3, which was reminiscent of authentic midbrain dopaminergic neuron progenitors.

Although robust methods have been introduced that produce enough modified cells, uncertainty remains for selecting the right cell types from human pluripotent cells for transplantation in terms of heterogeneity (33). There are only limited studies that have focused on selecting DA neurons for transplantation. One strategy facilitates isolation of a homogenous population of predefined cell types by sorting target cells based on their membrane proteins or glycans; however, this kind of method needs an in-depth understanding of the glycobiology or membrane proteins to be used as markers. Unfortunately, this information is not available for DA progenitors. Corin (atrial natriuretic peptide-converting enzyme) has previously been used as a brain floor plate marker to mediate sorting of the DA progenitors in a mixed culture of neuronal progenitors (34–36). The results have suggested that only 40% of sorted cells expressed TH and Nurr1 as the midbrain DA markers (35).

In a more recent study, researchers used 312 annotated antibodies and screened for antibodies that specifically enriched FOXA2-positive population. They found integrin-associated protein marks the FOXA2-positive cells (38). Our pure culture of TH neurons (>80% for TH and GIRK2 double-stained neurons) coupled with a shotgun proteomics approach (39) enabled us to identify proteins with higher abundancy in DA progenitors and neurons. In this study, we found several novel transcription factors that co-expressed with LMX1A positive cells such as RBM14 and TAF15, along with expression of TFs as previously reported in the dopaminergic areas of the brain such as XPO1 (40), FOXK1 (41), and PHF6 (42). The positive cells demonstrated a higher expression of TARDBP, a nuclear protein in which various mutations have been identified in fronto-temporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's, and PD (Table S7) (43). We examined the proteins that were exclusively localized to the plasma membrane and identified contactin 2, calbindin 2, flotillin 2, adipocyte plasma membrane associated protein, and neural cell adhesion molecule 1. We confirmed their expressions in our progenitors (Figs. 4 and 5, Table S8). Ganat et al. used the transgenic reporter system for HES5, NURR1, and PITX3 genes to purify dopaminergic progenitors and compared transcriptome data obtained from cells enriched from these three reporters (25). We identified CHRNA6, CHRNB3, Gucy2C, and Rit2 as highly expressed integral membrane transcripts (25), although GUCY2C and CHRN proteins predominantly expressed in the adult DA neurons and are not exclusively representatives of progenitors (44). We did not find any previously described membrane-associated transcripts in our proteomics study. This discrepancy could partly be attributed to our technical limitation of protein detection with lower expression. However, differences in developmental stages of the cells likely played a major role in altered expression of various proteins compared with the former studies. We found that PSA-NCAM was enriched in our proteomics data, and isolation of progenitors based on this membrane protein enriched for dopaminergic markers and transplantation of NCAM-positive progenitors could recover symptoms in PD animals (Fig. S5B and S5C). However, we observed clear reduction of rotation and increase in use of forelimb after NCAM-positive cell transplantation; we could not claim these cells are all dopaminergic and could be any type of neurons as reported by others, suggesting that membrane-associated proteins such as PSA-NCAM and ALCAM are not mDA progenitors specific and are expressed in other neuronal progenitors (36, 37). Therefore, we mainly focused on CNTN2 in this study as a more specific protein marker for DA progenitors. We have further tested isolated CNTN2+ progenitors to evaluate their functionality in vivo and validate our approach in finding reliable membrane proteins to purify authentic DA progenitors. Significant improvements in contralateral touches in CNTN2+ transplanted cells and consistent decline of drug-induced rotation in model animals are both indications of dopamine release from transplanted cells in the host brain. Although we noted no significant improvement in motor performance for the unsorted cells group, these cells could also be beneficial as sorted progenitors in terms of reducing rotation in the animals and dopamine production (just like NCAM-positive cells). Different performance of the sorted and unsorted cells in the two PD animal model assays could be due to the fact that motor impairment tests have different sensitivity, and drug induced rotation is more sensitive to the TH cell loss in the substantia nigra (SN) of animals than the spontaneous motor test with forelimb asymmetries in cylinder test (45). Indicating that apomorphine induced rotation more delicately reflected the number of integrated TH neurons in the lesion side, but in the cylinder test, more TH neurons integration needs to reflect in the forelimb asymmetries test. In our study, in both groups of animals that received transplants with sorted and unsorted cells, we had enough TH-positive neurons, which was probably sufficient for recovery and a decreasing number of rotations over time (as this test is more sensitive). However, in the forelimb asymmetries in the cylinder test, we just observed recovery in a group with more TH cells (CNTN2-sorted group) and small improvement in the other group. Therefore, we conclude that, even though we transplanted the same number of cells in both groups, the CNTN2-positive cells contain more dopaminergic progenitors, and it reflects as an improvement in the forelimb asymmetries test. Future studies in alternative animal models such as nigrostriatal bundle lesion models could be used to validate the beneficial effects of unsorted cells on behavioral outcomes (46). Our novel results that delineated significantly more TH/DAT double positive neurons in isolated CNTN2+ progenitors compared with unsorted cells further support the notion that purity of transplanted cells might be a more critical parameter to achieve recovery of motor abilities compared with the number of transplanted cells.

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD007837.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Royan Institute for their help, especially Fazel Samani and Ehsan Janzamin for their assistance doing the sorting experiments and Sahar Kiani lab for facilitating transplantations. This work was supported by a grant from Royan Institute to G.H.S. and H.B. and the Iranian Council of Stem Cell Research and Technology, the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF), and Iran Science Elites Federation to H.B, and Korean Research Foundation (grant no. 2017M3A9B4061408) and Chungcheonbuk-do to B.L.

Footnotes

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- PSC

- pluripotent stem cell

- LMX1A

- LIM homeoboxtranscription factor 1α

- PSA-NCAM

- polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule

- CNTN2

- contactin 2

- PD

- Parkinson's disease

- DA

- dopaminergic

- SN

- substantia nigra

- SNCA

- synuclein α

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- hESC

- human embryonic stem cell

- DTA

- diphtheria toxin A

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- Loxp

- locus of X(cross)-over in P

- Neo

- neomycin

- MTK

- MMCV thymidine kinase

- RA

- retinoic acid

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- GDNF

- glial-derived neurotrophic factor

- SHH

- Sonic Hedgehog

- RT

- room temperature

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- DAPI

- 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride

- CAN

- acetonitrile

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- GI

- gene identification

- ID

- identifier

- ECL

- electrochemiluminescence

- S.C.

- subcutaneous

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- NSAF

- normalized spectral abundance factors

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- KEGG

- Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FOXA2

- Forkhead box A2

- OTX2

- orthodenticle homeobox 2

- CORIN

- atrial natriuretic peptide-converting enzyme

- MAP

- microtubule-associated protein

- GRIK2

- glutamate ionotropic receptor kainate type subunit 2

- PITX3

- paired-like homeodomain 3

- TH

- tyrosine hydroxylase

- EN1

- Engrailed homeobox 1

- MSX1

- Msh homeobox 1

- WNT

- wingless-type MMTV integration site family

- NC

- neural cell

- PC

- progenitor cell

- TCA

- citric acid cycle

- TAF

- TATA-box binding factor

- RBM

- RNA binding motif

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- GSK

- glycogen synthase kinase

- VIM

- vimentin

- GAP43

- growth-associated protein 43

- FLOT

- flotillin

- CALB

- calbindin

- HB9

- motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1

- LHX

- LIM homeobox

- OLIG2

- oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2

- PAX6

- paired box 6

- OCT

- octamer-binding transcription factor

- NANOG

- Nanog homeobox

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- OHDA

- hydroxydopamine

- TUJ

- neuron-specific class III β-tubulin

- DAT

- dopamine transporter

- TAT

- transactivator of transcription

- XPO

- exportin

- PHF

- PHD finger protein

- TARDBP

- TAR DNA-binding protein

- HES

- Hes gene family

- NURR

- nuclear receptor-related

- CHRNA6

- cholinergic receptor nicotinic α6

- CHRNB3

- cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, β3

- GUCY

- guanylate cyclase 2

- aLCAM

- activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fitzpatrick K. M., Raschke J., and Emborg M. E. (2009) Cell-based therapies for Parkinson's disease: Past, present, and future. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 11, 2189–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ishii T., and Eto K. (2014) Fetal stem cell transplantation: Past, present, and future. World J. Stem Cells 6, 404–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freed C. R., Greene P. E., Breeze R. E., Tsai W. Y., DuMouchel W., Kao R., Dillon S., Winfield H., Culver S., Trojanowski J. Q., Eidelberg D., and Fahn S. (2001) Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 710–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olanow C. W., Goetz C. G., Kordower J. H., Stoessl A. J., Sossi V., Brin M. F., Shannon K. M., Nauert G. M., Perl D. P., Godbold J., and Freeman T. B. (2003) A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 54, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirkeby A., Grealish S., Wolf D. A., Nelander J., Wood J., Lundblad M., Lindvall O., and Parmar M. (2012) Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Reports 1, 703–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kriks S., Shim J. W., Piao J., Ganat Y. M., Wakeman D. R., Xie Z., Carrillo-Reid L., Auyeung G., Antonacci C., Buch A., Yang L., Beal M. F., Surmeier D. J., Kordower J. H., Tabar V., and Studer L. (2011) Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson's disease. Nature 480, 547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fathi A., Rasouli H., Yeganeh M., Salekdeh G. H., and Baharvand H. (2015) Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells toward dopaminergic neurons using recombinant LMX1A factor. Mol. Biotechnol. 57, 184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grealish S., Diguet E., Kirkeby A., Mattsson B., Heuer A., Bramoulle Y., Van Camp N., Perrier A. L., Hantraye P., Björklund A., and Parmar M. (2014) Human ESC-derived dopamine neurons show similar preclinical efficacy and potency to fetal neurons when grafted in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Stem Cell 15, 653–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doi D., Morizane A., Kikuchi T., Onoe H., Hayashi T., Kawasaki T., Motono M., Sasai Y., Saiki H., Gomi M., Yoshikawa T., Hayashi H., Shinoyama M., Refaat M. M., Suemori H., Miyamoto S., and Takahashi J. (2012) Prolonged maturation culture favors a reduction in the tumorigenicity and the dopaminergic function of human ESC-derived neural cells in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. Stem Cells 30, 935–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brederlau A., Correia A. S., Anisimov S. V., Elmi M., Paul G., Roybon L., Morizane A., Bergquist F., Riebe I., Nannmark U., Carta M., Hanse E., Takahashi J., Sasai Y., Funa K., Brundin P., Eriksson P. S., and Li J. Y. (2006) Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells to a rat model of Parkinson's disease: Effect of in vitro differentiation on graft survival and teratoma formation. Stem Cells 24, 1433–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elkabetz Y., Panagiotakos G., Al Shamy G., Socci N. D., Tabar V., and Studer L. (2008) Human ES cell-derived neural rosettes reveal a functionally distinct early neural stem cell stage. Genes Develop. 22, 152–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roy N. S., Cleren C., Singh S. K., Yang L., Beal M. F., and Goldman S. A. (2006) Functional engraftment of human ES cell-derived dopaminergic neurons enriched by coculture with telomerase-immortalized midbrain astrocytes. Nature Med. 12, 1259–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carlsson T., Carta M., Winkler C., Björklund A., and Kirik D. (2007) Serotonin neuron transplants exacerbate L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 27, 8011–8022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carta M., Carlsson T., Kirik D., and Björklund A. (2007) Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain 130, 1819–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Politis M. (2010) Dyskinesias after neural transplantation in Parkinson's disease: What do we know and what is next? BMC Medicine 8, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Politis M., Wu K., Loane C., Quinn N. P., Brooks D. J., Rehncrona S., Bjorklund A., Lindvall O., and Piccini P. (2010) Serotonergic neurons mediate dyskinesia side effects in Parkinson's patients with neural transplants. Science Translational Medicine 2, 38ra46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baharvand H., Ashtiani S. K., Valojerdi M. R., Shahverdi A., Taee A., and Sabour D. (2004) Establishment and in vitro differentiation of a new embryonic stem cell line from human blastocyst. Differentiation 72, 224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Costa M., Dottori M., Sourris K., Jamshidi P., Hatzistavrou T., Davis R., Azzola L., Jackson S., Lim S. M., Pera M., Elefanty A. G., and Stanley E. G. (2007) A method for genetic modification of human embryonic stem cells using electroporation. Nature Protocols 2, 792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. D'Haene B., Vandesompele J., and Hellemans J. (2010) Accurate and objective copy number profiling using real-time quantitative PCR. Methods 50, 262–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mudunuri U., Che A., Yi M., and Stephens R. M. (2009) bioDBnet: the biological database network. Bioinformatics 25, 555–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mirzaei M., Soltani N., Sarhadi E., George I. S., Neilson K. A., Pascovici D., Shahbazian S., Haynes P. A., Atwell B. J., and Salekdeh G. H. (2014) Manipulating root water supply elicits major shifts in the shoot proteome. J. Proteome Res. 13, 517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krijgsveld J., Gauci S., Dormeyer W., and Heck A. J. (2006) In-gel isoelectric focusing of peptides as a tool for improved protein identification. J. Proteome Res. 5, 1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zybailov B. L., Florens L., and Washburn M. P. (2007) Quantitative shotgun proteomics using a protease with broad specificity and normalized spectral abundance factors. Mol. Biosyst. 3, 354–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mirzaei M., Pascovici D., Atwell B. J., and Haynes P. A. (2012) Differential regulation of aquaporins, small GTPases and V-ATPases proteins in rice leaves subjected to drought stress and recovery. Proteomics 12, 864–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ganat Y. M., Calder E. L., Kriks S., Nelander J., Tu E. Y., Jia F., Battista D., Harrison N., Parmar M., Tomishima M. J., Rutishauser U., and Studer L. (2012) Identification of embryonic stem cell-derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons for engraftment. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2928–2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hedlund E., Pruszak J., Lardaro T., Ludwig W., Viñuela A., Kim K. S., and Isacson O. (2008) Embryonic stem cell-derived Pitx3-enhanced green fluorescent protein midbrain dopamine neurons survive enrichment by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and function in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Stem Cells 26, 1526–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pruszak J., Sonntag K. C., Aung M. H., Sanchez-Pernaute R., and Isacson O. (2007) Markers and methods for cell sorting of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural cell populations. Stem Cells 25, 2257–2268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersson E., Tryggvason U., Deng Q., Friling S., Alekseenko Z., Robert B., Perlmann T., and Ericson J. (2006) Identification of intrinsic determinants of midbrain dopamine neurons. Cell 124, 393–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Friling S., Andersson E., Thompson L. H., Jönsson M. E., Hebsgaard J. B., Nanou E., Alekseenko Z., Marklund U., Kjellander S., Volakakis N., Hovatta O., El Manira A., Björklund A., Perlmann T., and Ericson J. (2009) Efficient production of mesencephalic dopamine neurons by Lmx1a expression in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7613–7618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung S., Leung A., Han B. S., Chang M. Y., Moon J. I., Kim C. H., Hong S., Pruszak J., Isacson O., and Kim K. S. (2009) Wnt1-lmx1a forms a novel autoregulatory loop and controls midbrain dopaminergic differentiation synergistically with the SHH-FoxA2 pathway. Cell Stem Cell 5, 646–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakatani T., Kumai M., Mizuhara E., Minaki Y., and Ono Y. (2010) Lmx1a and Lmx1b cooperate with Foxa2 to coordinate the specification of dopaminergic neurons and control of floor plate cell differentiation in the developing mesencephalon. Dev. Biol. 339, 101–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niclis J. C., Gantner C. W., Alsanie W. F., McDougall S. J., Bye C. R., Elefanty A. G., Stanley E. G., Haynes J. M., Pouton C. W., Thompson L. H., and Parish C. L. (2017) Efficiently specified ventral midbrain dopamine neurons from human pluripotent stem cells under xeno-free conditions restore motor deficits in Parkinsonian rodents. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6, 937–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Niclis J. C., Gantner C. W., Hunt C. P. J., Kauhausen J. A., Durnall J. C., Haynes J. M., Pouton C. W., Parish C. L., and Thompson L. H. (2017) A PITX3-EGFP reporter line reveals connectivity of dopamine and non-dopamine neuronal subtypes in grafts generated from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 9, 868–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chung S., Moon J. I., Leung A., Aldrich D., Lukianov S., Kitayama Y., Park S., Li Y., Bolshakov V. Y., Lamonerie T., and Kim K. S. (2011) ES cell-derived renewable and functional midbrain dopaminergic progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9703–9708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Doi D., Samata B., Katsukawa M., Kikuchi T., Morizane A., Ono Y., Sekiguchi K., Nakagawa M., Parmar M., and Takahashi J. (2014) Isolation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopaminergic progenitors by cell sorting for successful transplantation. Stem Cell Rep. 2, 337–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ono Y., Nakatani T., Sakamoto Y., Mizuhara E., Minaki Y., Kumai M., Hamaguchi A., Nishimura M., Inoue Y., Hayashi H., Takahashi J., and Imai T. (2007) Differences in neurogenic potential in floor plate cells along an anteroposterior location: Midbrain dopaminergic neurons originate from mesencephalic floor plate cells. Development 134, 3213–3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bye C. R., Jönsson M. E., Björklund A., Parish C. L., and Thompson L. H. (2015) Transcriptome analysis reveals transmembrane targets on transplantable midbrain dopamine progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E1946–E1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lehnen D., Barral S., Cardoso T., Grealish S., Heuer A., Smiyakin A., Kirkeby A., Kollet J., Cremer H., Parmar M., Bosio A., and Knöbel S. (2017) IAP-based cell sorting results in homogeneous transplantable dopaminergic precursor cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 9, 1207–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liao L., McClatchy D. B., and Yates J. R. (2009) Shotgun proteomics in neuroscience. Neuron 63, 12–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simunovic F., Yi M., Wang Y., Stephens R., and Sonntag K. C. (2010) Evidence for gender-specific transcriptional profiles of nigral dopamine neurons in Parkinson disease. PLoS ONE 5, e8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wijchers P. J., Hoekman M. F., Burbach J. P., and Smidt M. P. (2006) Identification of forkhead transcription factors in cortical and dopaminergic areas of the adult murine brain. Brain Res. 1068, 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phani S., Gonye G., and Iacovitti L. (2010) VTA neurons show a potentially protective transcriptional response to MPTP. Brain Res. 1343, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rayaprolu S., Fujioka S., Traynor S., Soto-Ortolaza A. I., Petrucelli L., Dickson D. W., Rademakers R., Boylan K. B., Graff-Radford N. R., Uitti R. J., Wszolek Z. K., and Ross O. A. (2013) TARDBP mutations in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 312–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gong R., Ding C., Hu J., Lu Y., Liu F., Mann E., Xu F., Cohen M. B., and Luo M. (2011) Role for the membrane receptor guanylyl cyclase-C in attention deficiency and hyperactive behavior. Science 333, 1642–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Iancu R., Mohapel P., Brundin P., and Paul G. (2005) Behavioral characterization of a unilateral 6-OHDA-lesion model of Parkinson's disease in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 162, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Metz G. A., and Whishaw I. Q. (2002) Drug-induced rotation intensity in unilateral dopamine-depleted rats is not correlated with end point or qualitative measures of forelimb or hindlimb motor performance. Neuroscience 111, 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD007837.