Abstract

Purpose

In this work, the effects of sodium chloride (NaCl) on gene expression of planktonic Streptococcus mutans cells are investigated. Also assessed are the effects of NaCl on zeta potential of sound and demineralized dentin.

Methods

The relative level of glucosyltransferase B (gtfB), gtfC and gtfD transcription of S. mutans in the presence of NaCl was evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The osmolality of varying salt (NaCl) concentrations and their influence on the zeta potential of sound and demineralized dentin was investigated as well.

Results

NaCl significantly reduced the expression of gtfB and C genes in planktonic S. mutans; whereas, gtf D gene expression significantly increased in the presence of NaCl (P < 0.05). NaCl at concentrations of 37.5 mg/ml reduced zeta potential of demineralized dentin, while no significant decrease of zeta potential was found when sound dentin was exposed to this concentration.

Conclusion

NaCl reduces the expression of some gtfs in S. mutans and increases negative potential charge of demineralized dentin.

Keywords: Glycosylteransferase, Osmolality, Sodium chloride, Streptococcus mutans, Zeta potential

1. Introduction

Dental caries is a global public health problem and continues to be the most prevalent and costly oral infectious disease. Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans), as a principle causal agent of dental caries, is a member of normal oral flora and has the ability to adhere to tooth surfaces and form dental plaque.1 Normally, the bacterial cell surface and the surface of a tooth are negatively charged, resulting in repulsion of bacteria when approaching the surface of the tooth. However, S. mutans can synthesize large amounts of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), including glucans through glucosyltransferases (Gtfs), and adhere to glucan-coated surfaces. This bacterium harbors three distinct gtf genes responsible for the production of three Gtfs.2 The gtfB and gtfC genes encode GtfB and GtfC that produce mostly water-insoluble glucans, whereas the gtfD gene encodes an GtfD that synthesizes water-soluble glucans.3 GtfB, GtfC and glucans facilitate colonization of cariogenic bacteria and result in dental plaque formation on tooth surface.4

It has been shown that mutant S. mutans strains with defects in gtf genes (particularly gtfB and gtfC) have weaker cariogenic properties in vivo and thus, materials down-regulating the gtf genes (especially gtfB and C) may be able to effectively prevent the formation of dental biofilm and, consequently, dental caries. Thus, attempts are ongoing to find anti-plaque agents with no adverse biological effects. Among all the candidates, natural products are one of the main sources of antimicrobial materials.5 Salvadora persica and propolis extracts obtained from honey bees, as well as other new natural products, are frequently being studied with the hope of introducing them into clinical practices.6,7

NaCl is used as a safe antibacterial agent to prevent microbial growth in food and cosmetic industries since it decreases the water content, increases the ionic strength of the solution, reduces the solubility of oxygen in water, and makes the products more resistant to spoilage.8 Although there is evidence about the promising effect of NaCl mouth rinses in healing of oral mucosal lesions, it is not used as a routine mouth rinse in the critical care setting due to the resultant dryness.9 The aim of this study is to investigate (i) the effects of different concentrations of NaCl on the gene expression of S. mutans by means of qPCR and (ii) the influence of salt concentration on zeta potential of sound and demineralized dentin surface.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

NaCl powder (5–50 μm), chlorhexidine digluconate, and Tris-EDTA-lysozyme buffer were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, USA). Brain heart infusion (BHI) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were supplied by Merck (KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) by Liofilchem (Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy). RNA protect solution, RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini Kit, and QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). All primers (gtf genes and housekeeping genes) for real-time PCR were controlled with NCBI Primer Blast software and obtained commercially from Takapuzist Company (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea).

2.2. Agar diffusion method

The agar diffusion method was used for detecting the biological response to NaCl. For this test, S. mutans (ATCC 35668) suspension was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards and then inoculated on MHA. Using the sterile Pasteur pipette, 3 wells (6 mm in diameter) were punched on the agar surface. Next, one well was filled with NaCl powder and one with 50 μl of 0.2% CHX (as the positive or standard control group). One empty well in each plate served as the negative control. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the inhibition zones were measured using calipers. The test was conducted in triplicate and the experiment was repeated twice.

2.3. Broth macrodilution method and agar plating

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) were performed using the broth macrodilution method and agar plating according to NCCLS M27_P (1990). 200 mg/ml NaCl aqueous solution was prepared and sterilized using 0.22 μm Millipore filter. Then, the stock solution was serially diluted in 6 tubes filled with BHI broth to obtain final concentrations of 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 and 3.1 mg/mL. Addition of NaCl did not alter the pH. Note that these are the final concentrations of NaCl and account for the initial 0.5% NaCl that already exists in the media. Overnight broth culture of S. mutans were prepared according to 0.5 McFarland standard and added to the test tubes (final bacterial count of mixture in each tube was approximately 106 CFU/ml). There was also a tube containing BHI broth with the organism as the positive control and a tube containing BHI broth without the organism as the negative control. Treated bacterial cultures were then incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. Cultures were evaluated by turbidimetry and the lowest concentration of NaCl, which showed no turbidity, was identified as the MIC. Then, all tubes not showing visible growth were sub-cultured on BHI agar plates and incubated at 37 °C overnight to determine MBC. The lowest concentration that allowed no visible growth on the plate was determined as the MBC.

2.4. Evaluation of the expression of gtf genes via qPCR

Suspensions of S. mutans (equivalent to 1 McFarland) were prepared through an overnight broth culture. Based on the result of MIC and MBC, two concentrations of NaCl, i.e. 37.5 mg/mL (sub-MIC) and 75 mg/mL (sub-MBC), were prepared and inoculated with suspension of S. mutans. Non-treated (NaCl free) culture was considered as the positive control for gene expression. The tubes were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation (5000 g at 4 °C, 10 min), disrupted by adding Tris-EDTA-lysozyme buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Then, the bacterial total RNA was isolated and purified using RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using the NanoDrop instrument (mySPEC, Vienna, Austria). Isolated RNA was reverse transcribed (RT) using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNAs and negative controls (no-RT) were amplified using the SYBR®Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 200 nM of forward and reverse primers (Table 1). Amplification of specific products was performed on the ABI StepOne™ detection system (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Threshold cycle (Cт) values were determined, and relative expression levels were calculated according to the comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) method.

Table 1.

Specific primers used for qPCR.

| Genes | Nucleotide sequence (5’→3′) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gtfB | Forward: AGCAAATGCAGCCAATCTACAAAT | 60 | 96 |

| Reverse: ACGAACTTTGCCGTTATTGTCA | |||

| gtfC | Forward: GGTTTAACGTCAAAATTAGCTGTATTAGC | 60 | 91 |

| Reverse: CTCAACCAACCGCCACTGTT | |||

| gtfD | Forward: ACAGCAGACAGCAGCCAAGA | 60 | 94 |

| Reverse: ACTGGGTTTGCTGCGTTTG | |||

| Rec A | Forward: GCGTGCCTTGAAGTTTTATTCTTC | 60 | 75 |

| Reverse: TGTTCCCCGGTTCCTTAAATT |

2.5. Measurement of osmolality

Osmolality of the samples were measured in suitably diluted NaCl (37.5 mg/mL and 75 mg/mL) using a fully calibrated VAPRO® vapor pressure osmometer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Wescor, Inc., Logan, Utah).

2.6. Preparation of dentin and partially demineralized dentin powders

The dentin powders were prepared as described previously.10 In brief, sound teeth extracted for surgical or orthodontic purposes were collected. The teeth were washed with deionized water and immersed in 70% v/v ethanol. After rinsing, the soft tissue appendages on the root surface, enamel, cementum and pulp tissue were removed. The remaining dentin was milled together with dry ice and filtered using a 45-micron filter. For demineralization of dentin powder, 5%, 10% and 17% concentrations of EDTA were used, each for two to 5 min (step-wise sequential). At the time intervals for replacement of EDTA, samples were rinsed three times with deionized water. Sound and demineralized dentin powders were freeze-dried and stored.

2.7. Measurement of the zeta potential

The zeta-potential of different types of dentin were measured by a zetasizer (Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, Ltd., UK). Dry dentin particles (10 mg) were suspended in 1 ml distilled water or aqueous solution of NaCl (37.5 mg/ml and 75 mg/ml). The samples were sonicated to obtain a homogeneous suspension before the measurement. The measurements were conducted in triplicate.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Differences between the groups were analyzed by GraphPad Prism (V.6.01) (GraphPad software, Inc, La Jolla, USA) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the Tukey-Kramer post deviation test for all pairs. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Agar-well diffusion method

The mean diameter of the growth inhibition zone was 28 ± 1 and 14 ± 0.8 mm for CHX solution and NaCl, respectively.

3.2. MIC and MBC determination

NaCl MIC and MBC for planktonic cells were 50 mg/ml and 100 mg/ml, respectively. Thus, sub-MIC values were established in concentrations lower than 50 mg/ml. In 100 mg/ml, there was no cell growth.

3.3. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of gtf gene expression

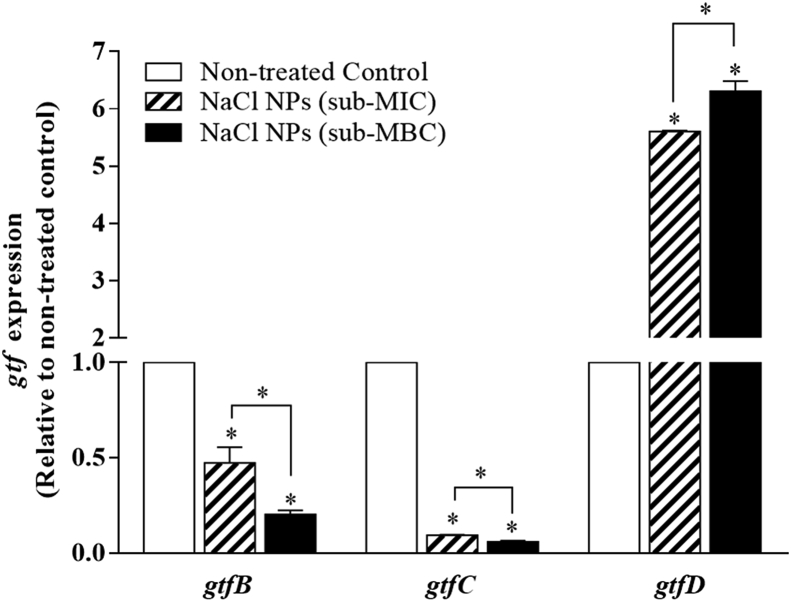

Fig. 1 shows the comparative effects of sub-MIC (37.5 mg/mL) and sub-MBC (75 mg/mL) concentrations of NaCl on gtf gene expression. The analysis revealed that the gtf genes were more abundantly expressed in non-treated S. mutans cultures. Both sub-MIC and sub-MBC concentrations significantly reduced the gtfB gene expression by 52.7 ± 14.2% and 79.7 ± 3.5%, respectively compared to the non-treated control (P < 0.05). The gtfC gene expression was down-regulated by 90.7 ± 0.6% and 94 ± 1%, in the presence of sub-MIC and sub-MBC concentrations, respectively. Interestingly, significant up-regulation of gtfD gene expression was observed in the presence of sub-MIC (5.6 ± 0.0 folds) and sub-MBC (6.3 ± 0.3 folds) concentrations of NaCl compared to non-treated control (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

qPCR analysis of gtfB, gtfC, and gtfD gene expression. Planktonic S. mutans were grown in absence (0, control) or presence of 37.5 mg/mL (sub-MIC) and 70 mg/mL (sub-MBC) concentrations of NaCl and subjected to qPCR analysis. The mRNA level of each gene was normalized to that of recA (internal control), and then the expression in treated cells was compared to that in non-treated control (value of 1). The results are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

3.4. Osmolality

The osmolality of distilled water, calculated from two independent readings, was determined to be 0 mosmol/kg. The addition of 37.5 and 75 mg/ml NaCl increased the osmolality to 1090 and 2248 mosmol/kg, respectively.

3.5. Zeta potential

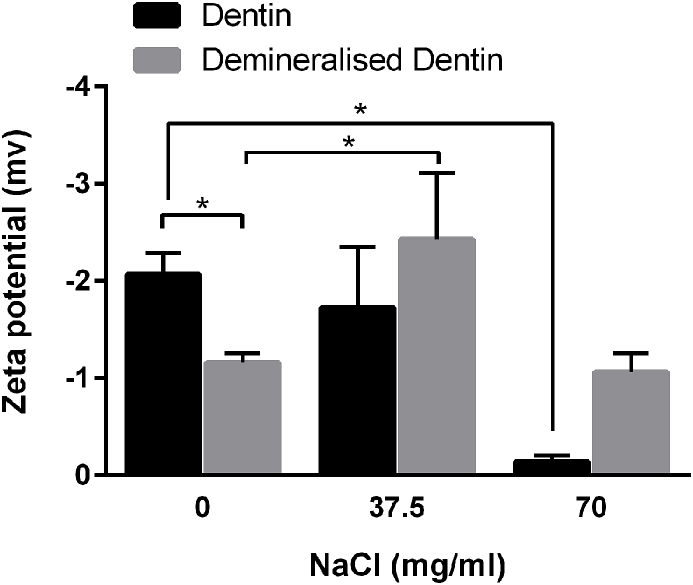

As shown in Fig. 2, the dentin particles showed higher negative charge in distilled water compared to high concentration solution of NaCl (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between zeta potential of dentin in water and 37.5 mg/ml NaCl (p > 0.05). Compared with sound dentin, demineralized dentin presented smaller negative charge; it showed higher negative charge in 37.5 mg/ml NaCl compared to distilled water (p < 0.05), while in the presence of 75 mg/ml NaCl the zeta-potential value of demineralized dentin reversed to positive charge.

Fig. 2.

Zeta Potential (in mV) of the samples. The results are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate whether solutions of sodium chloride can be used to inactivate S. mutans, and change surface charge of demineralized dentin.

NaCl is a traditional, widely used preservative compound with antibacterial properties. VAN DER WAAL et al. investigated synergistic combination of NaCl and potassium sorbate against E. faecalis biofilms and showed that NaCl with potassium sorbate destroyed E. faecalis biofilms within 1 h.11 Also, BAUTISTA-GALLEGO et al. carried out a quantitative investigation on the individual effects of sodium (NaCl), potassium (KCl), calcium (CaCl2), and magnesium (MgCl2) chloride salts against Lactobacillus pentosus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. CaCl2 and NaCl showed a similar and significant antimicrobial effect on the growth cycle, while KCl and MgCl2 were progressively less inhibitory.12 Likewise, it is reported that the growth of S. mutans is significantly reduced in the presence of Bamboo salt-pro (1 mg/mL), NaCl (1 mg/mL) or sodium fluoride (1%).13 In our research, we demonstrated the antibacterial activity of NaCl. The most effective factor in the antimicrobial activity of NaCl could be the high osmotic pressure it builds. Hyperosmotic pressure can inactivate bacteria in a biofilm due to reduction of the amount of available water to the microorganism.14 In our study, the osmolality of 75 and 37.5 mg/ml NaCl in distilled water was 1090 and 2248 mosmol/kg, respectively. LIU et al. found that 0.4 M of NaCl provided the sub-inhibitory level of osmolality that slightly retarded the growth rate of S. mutans.15 Our results showed that hyperosmotic conditions significantly inhibited the growth of S. mutans, and this inhibitory effect was related to change in gene expression. In a study by ABRANCHES et al., the hyperosmotic stress response of S. mutans was investigated by using BHI supplemented with 0.01, 0.1, 0.4 and 0.5 M NaCl, and real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis revealed that some of the genes were induced after exposure to 0.4 M NaCl.16 In the current study, we showed that NaCl significantly inhibited the expression of gtfB and especially gtfC. LIU et al. investigated the gene expression changes of S. mutans biofilm upon hyperosmotic challenge, and concluded that down-regulation of gtfB and comC were responsible for the observed biofilm dispersal.15 Down-regulation of gtfB and gtfC expression under hyperosmotic conditions can lead to a less condensed microbial population with reduced biomass.17 According to our results, the sub-MBC (above-MIC) concentrations of NaCl had a superior effect compared to the sub-MIC concentrations. However, the advantage of using sub-MIC concentrations in the oral environment is that they can exert antibacterial properties without killing or inhibiting the growth of normal microbial flora.

Beside gtf gene expression in S. mutans, another important factor associated with the progress of caries is the ionic charge of demineralized dentin. Since bacterial surfaces possess a negative charge and human teeth are also negatively charged, there would be a repulsive interaction between their surfaces. However, after demineralization of teeth, negatively charged microorganisms have a high affinity to the positively charged demineralized dentin. It seems likely that NaCl could also play a role in this matter. Zeta potential results in our study indicate that demineralization leads to a decrease of negative charge of the dentin and NaCl in 37.5 mg/ml concentration, can augment the negative charge of demineralized dentin. The results suggest that NaCl treatments of the demineralized dentin leading to increased negative surface charge may be effective in reduction of the electrostatic attraction between demineralized dentin and bacterial cells, therefore preventing the progression of dental caries. In this study, all the samples exhibited negative zeta potential. However, results show that when NaCl concentration was increased from 0 to 37.5 mg/ml, sound dentin exhibited no significant difference in the negative zeta potential. At a higher concentration of NaCl, the zeta potential of sound and demineralized dentin became positive. It seems that higher concentration of NaCl ions could cover the surface of particles and form an ion shield, which might increase the zeta potential.18

Bacterial attachment to the tooth surface is governed by both glucans and surface charge. Therefore, NaCl as a natural material could alter glucan production and inhibit progressive demineralization of dentin, thereby treating relevant diseases, such as dentin caries. Microorganisms, however, reside on the tooth surface in a biofilm configuration and have a more tolerant phenotype to elevated osmolality than planktonic cultures do.19 Therefore, the biofilm model should be considered in future studies.

There is also some concern about possible hypertension due to NaCl. In the future studies, the effect of combination of salt with other materials, with respect to this concern, could be considered. PARK et al. examined the possible effects of chitosan alone and in combination with NaCl in spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) models and showed the antihypertensive effect of a composition of NaCl plus chitosan.20 Additionally, microspheres can encapsulate large amounts of active substances and release them in a prolonged manner.21 Chitosan microsphere delivery system could be used with the goal of improving the beneficial effect of NaCl by prolonging its residence time at the site of action.

5. Conclusion

NaCl's effects against S. mutans depend on the concentration. At sub-MIC concentration, NaCl reduces the expression of some gtfs in S. mutans and increases negative potential charge of demineralized dentin.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dental Research Center, Research Institute of Dental Sciences, School of Dentistry, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 97-13439).

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Razieh Shahbazi for her skilled assistance.

References

- 1.Jacob M. Biofilms, a new approach to the microbiology of dental plaque. Odontology. 2006;94(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10266-006-0063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo H., Falsetta M.L., Klein M.I. The exopolysaccharide matrix: a virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J Dent Res. 2013;92:1065–1073. doi: 10.1177/0022034513504218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krzysciak W., Jurczak A., Koscielniak D., Bystrowska B., Skalniak A. The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:499–515. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moye Z.D., Zeng L., Burne R.A. Modification of gene expression and virulence traits in Streptococcus mutans in response to carbohydrate availability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:972–985. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03579-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabatabaei FS, Moezizadeh M, Javand F. Effects of extracts of Salvadora persica on proliferation and viability of human dental pulp stem cells. J Conserv Dent. 18(4):315-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Jafarzadeh Kashi T.S., Kermanshahi R.K., Erfan M., Vahid Dastjerdi E., Rezaei Y., Tabatabaei F.S. Evaluating the in-vitro antibacterial effect of Iranian propolis on oral microorganisms. Iran J Pharm Res (IJPR) 2011;10(2):363–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manas P., Pagan R. Microbial inactivation by new technologies of food preservation. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:1387–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry A.M., Davidson P.M. Beyond comfort: oral hygiene as a critical nursing activity in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(6):318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabatabaei F.S., Tatari S., Samadi R., Torshabi M. Surface characterization and biological properties of regular dentin, demineralized dentin, and deproteinized dentin. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27(11):164. doi: 10.1007/s10856-016-5780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Waal S.V., Jiang L.-M., de Soet J.J., van der Sluis L.W.M., Wesselink P.R., Crielaard W. Sodium chloride and potassium sorbate: a synergistic combination against Enterococcus faecalis biofilms: an in vitro study. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120(5):452–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bautista-Gallego J., Arroyo-Lopez F.N., Duran-Quintana M.C., Garrido-Fernandez A. Individual effects of sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium chloride salts on Lactobacillus pentiosus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth. J Food Protect. 2008;71(7):1412–1421. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.7.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin H., You H., Shin T.-Y., Kim H.-M., You Y.-O. Effect of Bamboo salt-pro on carries-inducing properties of Streptococcus mutans. Orient Pharm Exp Med. 2003;3(1):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Waal S.V., van der Sluis L.W.M., Özok A.R. The effects of hyperosmosis or high pH on a dual-species biofilm of Enterococcus faecalis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an in vitro study. Int Endod J. 2011;44(12):1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C., Niu Y., Zhou X. Hyperosmotic response of streptococcus mutans: from microscopic physiology to transcriptomic profile. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13(1):275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abranches J., Lemos J.A., Burne R.A. Osmotic stress responses of Streptococcus mutans UA159. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;255(2):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koo H., Xiao J., Klein M.I. Extracellular polysaccharides matrix — an often forgotten virulence factor in oral biofilm research. Int J Oral Sci. 2009;1(4):229–234. doi: 10.4248/IJOS.09086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan S.S., Mukherjee A., Chandrasekaran N. Studies on interaction of colloidal silver nanoparticles (SNPs) with five different bacterial species. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2011;87(1):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemesh M., Tam A., Steinberg D. Differential gene expression profiling of Streptococcus mutans cultured under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Microbiology. 2007;153(5):1307–1317. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S.-H., Dutta N.K., Baek M.-W. NaCl plus chitosan as a dietary salt to prevent the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Vet Sci. 2009;10(2):141. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2009.10.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torshabi M., Nojehdehian H., Tabatabaei F.S. In vitro behavior of poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid microspheres containing minocycline, metronidazole, and ciprofloxacin. J Invest Clin Dent. 2016;8(2) doi: 10.1111/jicd.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]