Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate the use of a mobile app in patients already using total body photography (TBP) to increase skin self-examination (SSE) rates and pilot the effectiveness of exam reminders and accountability partners.

Design:

Randomized controlled trial with computer generated randomization table to allocate interventions

Setting:

University of Pennsylvania pigmented lesion clinic.

Participants:

69 patients eighteen years or older with an iPhone/iPad, who already were in possession of TBP photographs.

Intervention:

A mobile app loaded with digital TBP photos for all participants, and either (1) the mobile app only, or (2) skin exam reminders, or (3) an accountability partner, or (4) reminders and an accountability partner.

Main outcome measure:

Change in SSE rates as assessed by enrollment and end-of-study surveys 6 months later

Results:

81 patients completed informed consent, with 12 patients not completing trial enrollment procedures due to device incompatibility, leaving 69 patients that were randomized and analyzed (mean age 54.3 [SD=13.9]). SSE rates increased significantly from 58% at baseline to 83% at 6 months (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.20–4.09), with no difference among the intervention groups. The group with exam reminders alone had the highest (94%) overall satisfaction, and the group with accountability partners alone accounted for the lowest (71%).

Conclusion:

A mobile app alone, or with reminders and/or accountability partners, was found to be an effective tool that can help to increase SSE rates. Skin exam reminders may help provide a better overall experience for a subset of patients.

1. Introduction

The importance of home skin exams is highlighted by a number of studies supporting an association between higher skin self-examination (SSE) rates and thinner, more treatable, melanomas at diagnosis [1–3]. Yet, SSE rates by adults are as low as 10% in high-risk groups such as those who warrant professional total body photography (TBP) [4,5]. With TBP, the patient receives 20 to 50 photographs produced with professional lighting and a contrasting background to optimize image quality. The patient uses these photographs to compare against when checking for new or changing pigmented skin lesions [6].

Several studies suggest that the use of photographs, including TBP, as well as patient education on skin exams and melanoma may be effective interventions to increase skin self- examination (SSE) rates [7–12]. Our previous work demonstrated the efficacy of both printed TBP photos and a mobile app loaded with TBP photos, at increasing SSE rates [13]. However, the previous study was limited to patients who had never had TBP prior to the study, with the potential that initial use could stem from a motivating event such as a new diagnosis or recommendation.

Accordingly, we investigated the use of a mobile app loaded with TBP photos in a different patient population: those with established TBP use for skin self-exams, in order to evaluate the generalizability of our previous findings. In addition, an extensive body of research [14] underpinned by social and health behavior models such as the theory of reasoned action [15,16], the theory of planned behavior [17,18], and the model of interpersonal behavior [19] highlight the influence that social pressure, or subjective norms, can have on patient behavior. Consequently, we piloted the use of skin exam reminders and personalized skin exam performance reports sent to accountability partners as potential means of enhancing perceived social pressures and improving self-exam rates.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included adults age eighteen years or older that presented to the Penn Dermatology Pigmented Lesion Clinic with an iPhone/iPad and who already were in possession of TBP photographs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier - NCT02520622). With the approval of the University of Pennsylvania IRB, the study occurred between August 2015 and January 2017 when target enrollment was reached. We targeted enrollment of 70 patients based on prior literature successfully assessing the impact of image-based interventions on SSE rates [8,9].

Immediately after completion of the enrollment survey, all patients were set up with a mobile app loaded with their TBP photos, and then were randomized by a study coordinator (using Stata) into one of four groups that consisted of the following interventions: (1) the mobile app only, (2) the receipt of monthly skin exam reminders, (3) an accountability partner that would receive a monthly performance report of their skin exam progress, or (4) a combination of both monthly reminders and a report to an accountability partner. All groups could continue to use the standard of care at Penn, consisting of printed photographs and a CD containing digital copies. The primary outcome variable was the change in skin self-examination rates as assessed by enrollment and end-of- study surveys. The secondary outcome variable was patient satisfaction as assessed by the end-of-study survey.

2.1. Study Interventions

The patient’s professionally taken TBP photographs were loaded into the mobile app where they were encrypted, password-protected, and stored within the app on their device. The app was developed for iOS only (based on clinic surveys showing a majority of patients with iOS), and devices released before the iPhone 5s or iPad Air were not supported in order to simplify app development and support. The app allowed patients to magnify photos, to make side-by-side comparisons, and to flag photo areas for follow-up with their clinician. The app also provided skin cancer and skin exam education and tracked how frequently each of the photos were viewed as part of a skin exam. Through the app’s communication with Way to Health, an automated information technology platform that has been used in prior behavioral intervention studies [20–23], this skin exam data was used to email monthly performance reports to accountability partners, depending on the study arm. The Way to Health platform also distributed monthly skin exam reminders by email and/or text message depending on the study arm.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

To evaluate the effect of the interventions, we compared the change from enrollment to follow-up in the percentage performing regular skin self-examinations in each group. We considered participants to be performing regular skin exams if they conducted a self- examination at least four times in the past six months. We used GEE logistic regression (STATA version 14, StataCorp, College Station, Texas) to examine changes in our primary outcome (SSE rates) while accounting for correlation between longitudinal responses within individuals. Fisher’s exact tests were used to evaluate differences in patient satisfaction between intervention groups.

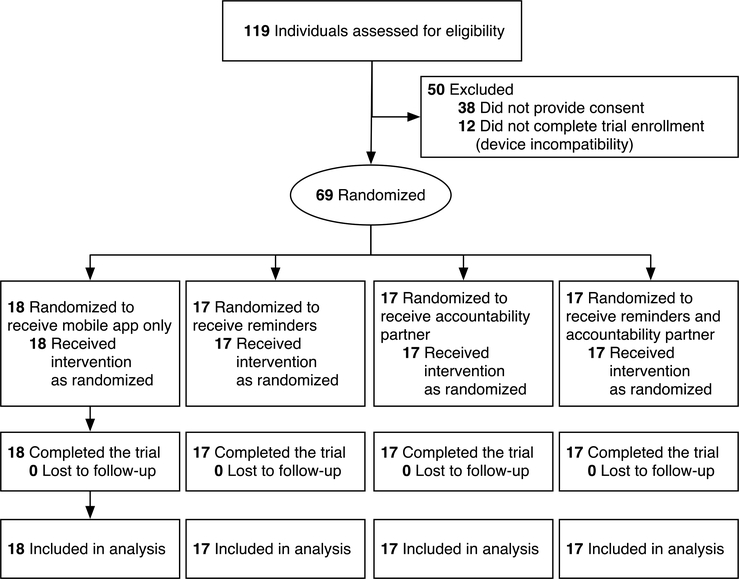

3. Results

From August 2015 to April 2016, 68% [81/119] of patients agreed to participate in this study and provided informed consent (see Figure 1). Of the 81 patients, 12 did not complete trial enrollment procedures due to device incompatibility, leaving 69 patients that were randomized and analyzed. Reasons for not participating included concerns about privacy/security, not being very tech savvy, not wanting to change their routine, and not wanting to get involved with a research study. Table one presents the study population characteristics, with none differing significantly across the four groups. The mean age of participants was 54.3 (SD=13.9). All study patients identified as Caucasian, and 44% had graduate or professional training. The average time each participant was a patient with the PLG clinic was 8.4 years (SD=7.9). The average time each participant had TBP photos was 8.5 years (SD=7.6) with the shortest period being 170 days. 83% of patients started using TBP within one year of their entrance into the PLG clinic. The average time between when patients started in the study to when they completed the end-of-study survey was 226 days (7.52 months).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1:

Characteristics of patients with total body photographya

| Characteristic | Mobile App Only n=18 n (%) |

Reminders n=17 n (%) |

Social Support n=17 n (%) |

Combined n=17 n (%) |

p- valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 11 (61.1) | 14 (82.4) | 10 (58.8) | 9 (52.9) | 0.3 |

| Male | 7 (38.9) | 3 (17.7) | 7 (41.2) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–44 | 5 (27.8) | 7 (41.2) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.8) | 0.25 |

| 45–54 | 3 (16.7) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (17.7) | 2 (11.8) | |

| 55+ | 10 (55.6) | 5 (29.4) | 10 (58.8) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| white non-Hispanic | 18 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 1 |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 2(11.1) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (17.7) | 0.74 |

| Some college, college graduate | 9 (50.0) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (41.2) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Graduate or professional training | 7 (38.9) | 9 (52.9) | 9 (52.9) | 5 (29.4) | |

| New patient to the pigmented lesion clinicc | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.38 |

| No | 18 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 16(94.1) | |

| Time as a pigmented lesion clinic patient | |||||

| Less than 1 year | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.58 |

| 1 to 5 years | 7 (38.9) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (41.2) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Greater than 5 years | 11 (61.1) | 8 (47.1) | 10 (58.8) | 11 (64.7) | |

| Time with TBP photos | |||||

| Less than 1 year | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 0.71 |

| 1 to 5 years | 9 (50.0) | 7 (41.2) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Greater than 5 years | 9 (50.0) | 8 (47.1) | 11 (64.7) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Use of mole-mapping software or diagrams in last 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.9) | 4 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) | 0.22 |

| No | 17 (94.4) | 16 (94.1) | 13 (76.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Use of computer/device for skin exams in last 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 2(11.1) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.58 |

| No | 16 (88.9) | 16 (94.1) | 16 (94.1) | 17 (100.0) | |

| History of melanoma or other skin cancer | |||||

| Yes | 16 (88.9) | 14 (82.4) | 17 (100.0) | 14 (82.4) | 0.33 |

| No | 2(11.1) | 3 (17.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.7) | |

| TBP modality currently used most | |||||

| Printed photographs | 13 (72.2) | 15 (88.2) | 17 (100.0) | 14 (82.4) | 0.28 |

| Digital photographs | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| None | 4 (22.2) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.7) |

The following characteristics occurred in the majority of patients and did not differ significantly between study groups: described skin self-exams as beneficial, felt their knowledge of skin cancer risks and how to perform an exam was good, felt skin exams were difficult to perform but were confident in performing them, had an abnormal skin lesion/biopsy, had help from a partner during skin exams, received education on skin exams/skin cancer, had a pigmented lesion clinic appointments in the past 6 months, had skin exams by a clinician in the past year, and had regular skin self-exams recommended to them by a dermatologist. Most participants (55%) had a 1st degree relative with a history of skin cancer.

Pearson’s chi-squared test

Patients that are not new to the pigmented lesion clinic have had more than one appointment

Table two shows that SSE rates increased significantly over the 6-month study period (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.20–4.09) with no difference between the intervention groups. Overall, 58% of our study population, regardless of study arm, performed regular skin exams at baseline, increasing to 83% six months later. Participation in the study, with access to a mobile app and performance reports, may have helped patients complete more thorough skin exams, with significant SSE rate increases for difficult to examine areas such as the lower back (75% increased to 92%; p-value = 0.008) and back of legs (80% increased to 95%; p- value = 0.006).

Table 2:

Impact of interventions on self-examination rates in patients who have total body photography

| Model Characteristic | Baselinea | 6 Monthsb | Odds Ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Visitc | ||||

| Baseline | 69 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 6-month | 65 (100.0) | 2.64 (1.20, 4.10) | <0.001 | |

| Intervention | ||||

| Mobile app only | 18 (26.1) | 17 (26.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Reminders | 17 (24.6) | 16 (24.6) | −0.98 (−2.65, 0.69) | 0.25 |

| Accountability partner | 17 (24.6) | 17 (26.2) | −0.48 (−2.25, 1.29) | 0.60 |

| Combined (Reminders + Accountability partner) | 17 (24.6) | 15 (23.1) | −1.27 (−3.01,0.48) | 0.15 |

| Number of skin exams in last 6 months | ||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 1 | 5 (7.3) | 1 (1.5) | Xd | |

| 2 | 9 (13.0) | 3 (4.6) | −0.23 (−2.32, 1.86) | 0.83 |

| 3 | 15 (21.7) | 7 (10.8) | −0.43 (−2.40, 1.53) | 0.67 |

| 4+ | 40 (58.0) | 54 (83.1) | 4.28 (2.10, 6.47) | <0.001 |

Number and percentage of participants at baseline, regardless of intervention, unless specified otherwise

Number and percentage of participants at 6 months, regardless of intervention, unless specified otherwise

Visit describes the impact of study participation, while controlling for longitudinal data, the intervention, and the number of skin exams in the last 6 months

Insignificant number of observations for adequate statistical analysis

While SSE rates were similar across the study groups, satisfaction rates were highest in the reminders group and lowest in the accountability partner group, with rates of 94% and 71% respectively (table three). When these two groups were compared directly in post-hoc analysis, the difference in satisfaction between the reminders and accountability partner groups trended toward significance (p-value = 0.085), although this study was small and may have been underpowered to detect significant differences in satisfaction if they in fact existed. In addition, anticipated future use of the app differed significantly between the interventions (p-value = 0.049), with the accountability partner group having the lowest future use rate of 76%. Over 80% of study participants reported having help from a partner during skin self-examination with no significant difference between intervention groups.

Table 3:

Impact of interventions on patient satisfaction

| Mobile-only N (%) |

Reminders N (%) |

Accountability N (%) |

Combined N (%) |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction | |||||

| Very dissatisfied, Dissatisfied, Neutral | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.2) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (13.3) | 0.34 |

| Satisfied, Very Satisfied | 13 (86.7) | 15 (93.8) | 12 (70.6) | 13 (86.7) | |

| Anticipated future use (next 5 years) | |||||

| Anticipated future use (next 5 years) Never, Rarely, Sometimes |

0(0) | 1 (6.2) | 4 (23.5) | 0(0) | 0.049 |

| Most of the time, Always | 15 (100) | 15 (93.8) | 13 (76.5) | 15 (100) |

Fisher’s exact test (extended to m × n table using Stata)

4. Discussion

We demonstrated that a mobile app alone, or with reminders and/or accountability partners, can be an effective method of increasing skin exam rates in a patient population that had an average of 8.5 years of printed TBP use (versus a population that was new to TBP in our previous study) [13]. This improvement in exam rates without significant intergroup differences suggests that participation in the study alone, or the Hawthorne effect, may have played a role in the observed SSE rate increase. Future studies could evaluate this potential effect by including a crossover point where patients would revert back to their baseline skin exam modality after being randomized to an intervention. A sustained increase in skin exam performance after reverting to a baseline skin exam modality may help elucidate any potential Hawthorne effect.

While exam rates did not differ significantly between study groups, anticipated future use of the mobile app differed significantly, with the accountability partner group having the lowest future use rate. Additionally, overall satisfaction was highest in the reminders group and lowest in the accountability partner group, with patients anecdotally volunteering that the exam reminders were invaluable. This satisfaction with reminders was consistent with other studies demonstrating the efficacy of smartphone reminders in helping patients increase SSE rates, increase sunscreen use, lose weight, and show up for clinic appointments [24–27].

Given the occasional displeasure patients expressed upon being randomized into the accountability partner group, we suspect that the relative decrease in satisfaction with this intervention may stem from patient discomfort with giving up privacy and having their skin exam habits disclosed to a third party (who may or may not be the same person as their exam partner). Also, over 80% of study participants had help from a partner when performing skin exams, with no significant difference between study arms. Consequently, we could not draw conclusions about the potential benefit of having a skin exam partner based on this study.

This study’s limitations include the reliance on self-reported responses to surveys and the lack of blinding to the intervention. Additionally, the study group was a self-selected group of patients that were interested in participating in a clinical trial using a mobile app for skin exams. Consequently, it is possible that the significant increase in SSE rates may not generalize well to a patient population not interested in this trial. We were encouraged, however, by the trial’s 68% participation rate and that study participants represented a wide range of age and technical abilities.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we piloted the effectiveness of a mobile app alone, or with skin exam reminders and/or accountability partners, at increasing SSE rates. After 6 months of follow-up, our analysis demonstrated the efficacy of a mobile app at increasing SSE rates in a different patient population than our previous study. Future research should investigate whether this impact can be sustained over longer periods of time and should consider reverting to baseline skin exam modalities after intervention use in order to better elucidate any potential Hawthorne effect. Regardless, these results, along with the high satisfaction rates associated with the mobile app and exam reminders, further established mobile technology as a viable option for patients to use and for clinicians to offer in support of regular skin self-exams.

Key points.

Skin self-exam (SSE) rates are low, even in high-risk groups such as those who warrant professional total body photography (TBP).

In this randomized controlled trial, a mobile app alone, or with reminders and/or accountability partners, was found to be an effective tool to help increase SSE rates in patients using TBP for their skin exams.

Skin exam reminders were associated with the greatest overall patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics award TL1TR000138, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health grant UL1TR000003.

Funding: A.J.M is supported in part by the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number TL1TR000138 and Grant Number UL1TR000003. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Science or the National Institutes of Health.

E.Y.C. is supported by the Dermatology Foundation Dermatopathology Research Career Development Award.

Footnotes

6 Compliance with Ethical Standards

6.1 Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Conflict of Interest: Author A.J.M, author E.Y.C., author M.E.M., author Z.A.K., and author C.L.K declare that they have no conflict of interest.

6.2 Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals

Ethical approval: This study occurred with the approval of the University of Pennsylvania IRB. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

6.3 Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier - NCT02520622.

References

- 1.Wang SQ, Hashemi P. Noninvasive imaging technologies in the diagnosis of melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller AC, Swetter SM, Brooks K, Demierre M-F, Yaroch AL. Screening, early detection, and trends for melanoma: Current status (2000–2006) and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:555–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, Geller AC. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: Current status (2007–2013) and future directions: Part I. Epidemiology, high-risk groups, clinical strategies, and diagnostic technology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:599.el–599.el2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstock MA, Risica PM, Martin RA, Rakowski W, Smith KJ, Berwick M, et al. Reliability of assessment and circumstances of performance of thorough skin self-examination for the early detection of melanoma in the Check-It-Out Project. Prev Med. 2004;38:761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamidi R, Cockburn MG, Peng DH. Prevalence and predictors of skin self-examination: prospects for melanoma prevention and early detection. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:993–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melanoma of the Skin - Cancer Stat Facts [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

- 7.Geller AC, Emmons KM, Brooks DR, Powers C, Zhang Z, Koh HK, et al. A randomized trial to improve early detection and prevention practices among siblings of melanoma patients. Cancer. 2006;107:806–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Berwick M, Halpern AC. Patient adherence to skin self- examination: effect of nurse intervention with photographs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:152–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstock MA, Nguyen FQ, Martin RA. Enhancing Skin Self-Examination with Imaging: Evaluation of a Mole-Mapping Program. J Cutan Med Surg Inc Med Surg Dermatol. 2004;8:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay JL, Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Halpern AC. Psychosocial Mediators of a Nurse Intervention to Increase Skin Self-examination in Patients at High Risk for Melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2006;15:1212–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dubois M, Richard M-A, Bonnelye G, Grob J-J. Cognitive training with photographs as a new concept in an education campaign for self-detection of melanoma: a pilot study in the community. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1099–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KB, Weinstock MA, Risica PM. Components of a successful intervention for monthly skin self- examination for early detection of melanoma: The “Check It Out” Trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marek AJ, Chu EY, Ming ME, Khan ZA, Kovarik CL. Impact of a Smartphone Application on Skin Self-Examination Rates in Patients that are New to Total Body Photography: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2018 Feb 12];0. Available from: http://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(18)30211-1/abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBarr KA. A Review of Current Health Education Theories. Californian J Health Promot. 2004;2:14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishbein M A theory of reasoned action: some applications and implications. Neb Symp Motiv Neb Symp Motiv. 1980;27:65–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbein M A, Ajzen I Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. 1975.

- 17.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior Action Control [Internet]. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 1985. [cited 2018 Jun 26]. p. 11–39. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triandis HC Interpersonal behavior. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kullgren JT, Troxel AB, Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Norton LA, Wesby L, et al. Individual- Versus Group-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kullgren JT, Harkins KA, Bellamy SL, Gonzales A, Tao Y, Zhu J, et al. A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of financial incentives and peer networks to promote walking among older adults. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2014;41:43S–50S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sen AP, Sewell TB, Riley EB, Stearman B, Bellamy SL, Hu MF, et al. Financial Incentives for Home-Based Health Monitoring: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:770–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Rosin R, Bellamy SL, Small DS, Fletcher MA, et al. A Randomized Trial of Social Comparison Feedback and Financial Incentives to Increase Physical Activity. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2016;30:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong AW, Watson AJ, Makredes M, Frangos JE, Kimball AB, Kvedar JC. Text-Message Reminders to Improve Sunscreen Use: A Randomized, Controlled Trial Using Electronic Monitoring. Arch Dermatol [Internet]. 2009. [cited 2018 Feb 2];145. Available from: http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archdermatol.2009.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, Dillon L, Zabinski M, Rock CL, et al. A Text Message-Based Intervention for Weight Loss: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009; 11 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koshy E, Car J, Majeed A. Effectiveness of mobile-phone short message service (SMS) reminders for ophthalmology outpatient appointments: Observational study. BMC Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2008. [cited 2018 Feb 2];8 Available from: http://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2415-8-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youl PH, Soyer HP, Baade PD, Marshall AL, Finch L, Janda M. Can skin cancer prevention and early detection be improved via mobile phone text messaging? A randomised, attention control trial. Prev Med. 2015;71:50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]