Abstract

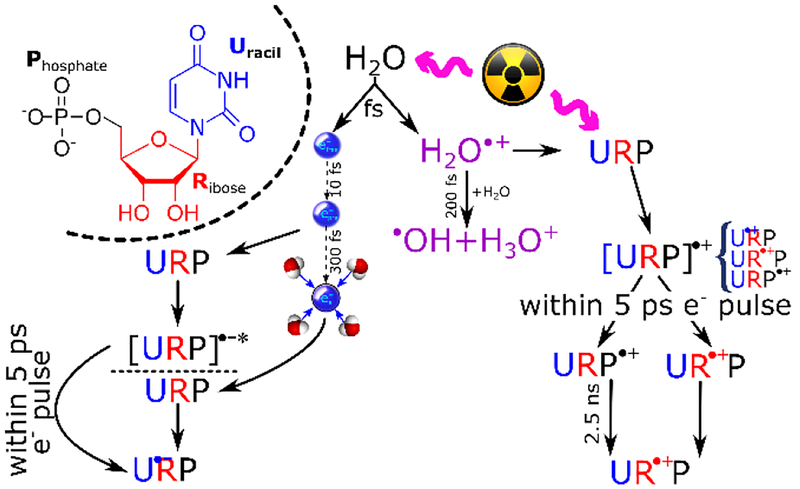

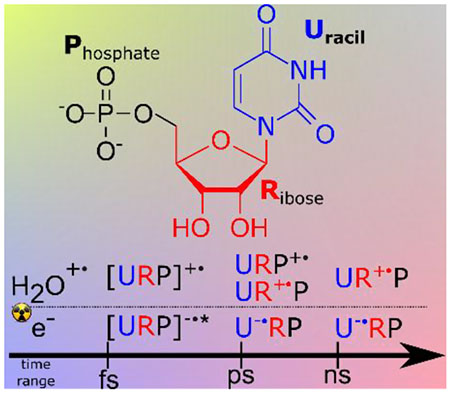

The primary localization process of radiation-induced charges (holes (cation radical sites) and excess electrons) remains poorly understood, even at the level of monomeric DNA/RNA-models, in particular, in an aqueous environment. Herein, we report the first spectroscopic study of charge transfer occurring in radiolysis of aqueous uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP) solutions and its components: uridine, uracil, ribose and phosphate. Our results show that: prehydrated electrons effectively attach to base site of UMP; the holes in UMP formed by either direct-ionization or via reaction of UMP with the radiation-mediated water cation radical (H2O•+) facilely localize on the ribose site, despite the fact that a part of them were initially created either on the phosphate or uracil. The nature of phosphate-to-sugar hole transfer is characterized as a barrierless intramolecular electron transfer with a time constant of 2.5 ns, while the base-to-sugar hole transfer occurs much faster, within 5 ps electron pulse.

TOC GRAPHICS

In a biological medium, the direct-type effects leading to cellular DNA/RNA damage by ionizing radiation result from two sorts of events occurring in ultrafast regime (< 1 ps): (a) direct ionization of DNA, or oxidation by water cation radicals (H2O•+) formed within the DNA hydration shell, and (b) interaction of pre-thermalized electrons with the DNA molecule.1,2 Direct-type effects cause the formation of cationic, anionic, and neutral radicals,3 accounting for the majority of DNA/RNA damages: strand breaks and base damages.4–6 Besides, cascades of low-energy electrons (LEEs; 0–20 eV) also lead to strand breaks through dissociative electron attachment.7,8 However, studies of direct-effects were often limited to the gas and condensed phases or crystalline state of target molecules.7,8

Radiation ionizes the molecular units of a nucleotide non-specifically with a probability proportional to its electron fraction (fs): about 57% of the ionizations will occur at the 2′-deoxyribose-phosphate backbone while the remaining 43% ionizations are distributed among the bases.3,9 Thus, the detailed mechanism of charge transfer processes that should take place among the sites of sugar, phosphate and base have not been much elucidated experimentally at a single molecule level. The global concentration of macromolecules (DNA, RNA, proteins etc.) in cell nucleus ranges from 65 to 220 mg/mL; therefore, cell nucleus is not a dilute aqueous solution. Furthermore, dsDNA in cellular systems is highly packaged in nucleosomes with the DNA wrapped around the histone protein core that forms the basic unit of the chromatin structure.10 As a result, the sophisticated time-resolved techniques that are applied in highly concentrated aqueous solutions of DNA-models become necessary to investigate the direct-type effects of DNA in bulk phase and to account for the initial hole localization and presolvated electron (epre−, time constant of solvation ca. 300 fs11) attachment concurrently occurring in sub-picosecond time scales. In fact, this goal may not be easily achieved by applying the cutting-edge femtosecond laser spectroscopy;12 although a laser pulse is able to ionize the aqueous system through a multi-photon process and can provide a femtosecond time resolution, most of the light can be preferentially absorbed by the abundant purine or pyrimidine groups, resulting in a larger extent of photoexcitation of bases. In contrast, laser-driven picosecond electron pulse radiolysis coupled with transient optical absorption spectroscopy has recently been proven to be a very suitable technique for exploring the electron/H2O•+ transfers and hence, direct-type effects that occur in solution, by detecting the formation of the corresponding radicals.12–14

In this work, we performed picosecond electron pulse (5 ps) radiolysis measurements (see SI for more details) of various concentrations of uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP), uridine (Urd), uracil (U), ribose (Rib) and phosphate (P). We chose uracil derivatives by taking advantage of their unique solubility in water compared to other nucleotide/sides. The direct ionization of UMP as well as interaction of UMP with H2O•+ become experimentally observable at high concentration of UMP which is associated with high fs (Figure SI1). Furthermore, the interaction of epre− with UMP as a model of reductive DNA/RNA damage pathway was studied at similar timescale. Most importantly, this work reports the direct observation of the initial charge localization site and subsequent intramolecular charge transfer at a single nucleotide level in aqueous solution for the first time.

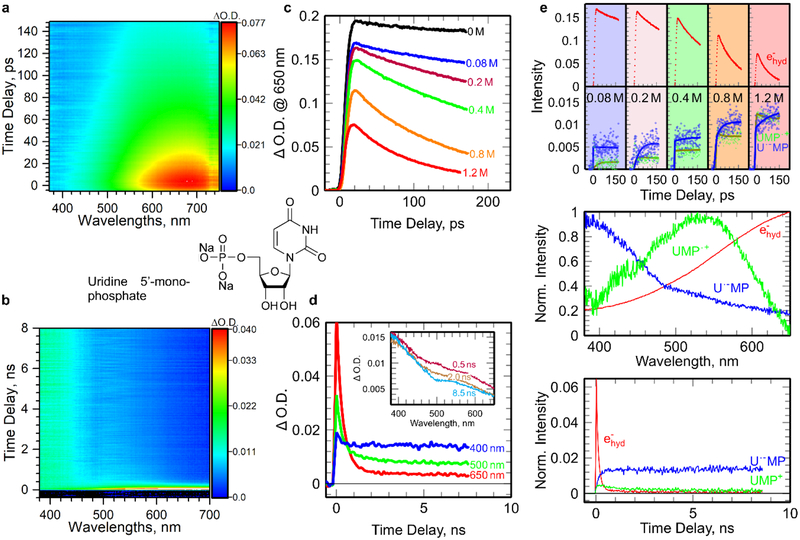

The radiation track is surrounded both by LEEs and holes, which can either recombine with each other or localize in the energetically favorable regions.2–9 At high concentration, UMP molecule effectively scavenges both epre− and ehyd−. The global analyses of pulse-probe matrix data (Figure 1a and 1b) clearly show that immediately after irradiation of UMP solutions, three distinguishable species, absorbing in 380–700 nm range are formed (Figure 1e). The strong and featureless broad absorption band at ca. 710 nm (red curve, Figure 1c) is the typical spectra of ehyd−. Experimentally, the decrease of ehyd− formation yield with increasing UMP concentration (Figure 1c), provides the direct evidence that a significant fraction of epre− is captured by UMP in competition to the solvation of epre− to ehyd− with a rate constant ~ 5 × 1012 M−1·s−1 (Figure S2), the highest one of epre− scavenging rate comparing to DNA nucleotides.12 The ultrafast attachment of epre− to UMP forms the transient UMP negative ion (radical, [UMP]*•−). At longer time-scales, ehyd− is fully scavenged by UMP, yet a small residual transient absorption signal (Figure 1d) suggests the presence of other intermediates, e.g., either products of [UMP]*•− dissociation or non-dissociative anion radicals ([UMP]•−). The transient (blue spectrum) which show predominant absorption in the UV region can be attributed to either [UMP]*•− or [UMP]•−.12,15 In addition, one should always consider formation of [UMP]•+, by either direct ionization or via reaction between UMP and H2O•+ at high UMP concentration. Species absorbing at 520 nm could be attributed to phosphate-center radical formed by direct oxidization. The assignment is based on the fact the intermediate at 520 nm found to be present only in UMP (Figure 1c), and is not detected in Urd and U solutions (Figure 2c and Figure SI3). Its spectral shape is nearly identical with that of phosphate radicals (H2PO4•).14,16 Also, the cation radical of ribose absorbs in the UV range below 300 nm and the cation radical of U has a different spectral shape (Figure SI5). These results suggest that the phosphate moiety in sugar-phosphate backbone plays an important role for trapping the hole.

Figure 1.

Picosecond pulse radiolysis of UMP aqueous solutions at ambient conditions. (a-b) Picosecond pulse radiolysis transient absorption profiles on picosecond and nanosecond timescales for 1.2 M aqueous UMP solutions, respectively; (c) transient absorption at 650 nm kinetics on picosecond timescale for aqueous UMP (0.08 to 1.2 M) solutions; (d) transient absorption kinetics on nanosecond timescale at different wavelengths for 1.2 M UMP; (e) global data analysis of two-dimensional transient absorption profiles in (a) and (b) giving the spectra and the kinetics of the three species (ehyd− in red, U•−MP in blue and UMP•+ in green) involved in the mechanism of charge localization on UMP.

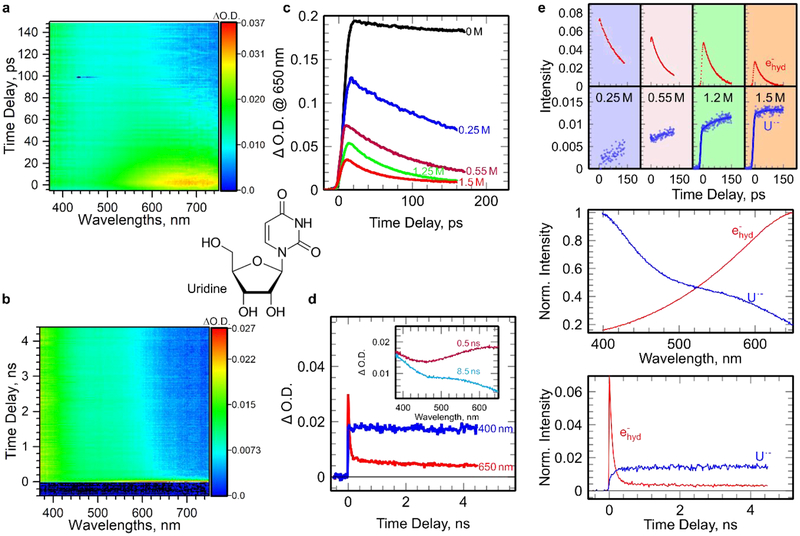

Figure 2.

Picosecond pulse radiolysis of Urd aqueous solutions at ambient conditions. (a-b) Picosecond pulse radiolysis transient absorption profiles on picosecond and nanosecond timescales for 1.5 M aqueous Urd solutions, respectively; (c) transient absorption at 650 nm kinetics on picosecond timescale for aqueous UMP (0.25 to 1.5 M) solutions; (d) transient absorption kinetics on nanosecond timescale at different wavelengths for 1.2 M Urd; (e) global data analysis of two-dimensional transient absorption profiles in (a) and (b) giving the spectra and the kinetics of the two species (epre− in red and U•−rd in blue) involved in the mechanism of electron localization on Urd.

To identify the localization site of the excess electron on UMP, we have investigated uridine, uracil, ribose, and phosphate aqueous solutions as models. Ribose and phosphate do not react with epre− nor ehyd−. Global data analyses isolate spectra of U, Urd and UMP anion radicals, formed in reactions of epre− and ehyd− (Figure 2 and SI3) with these compounds, and shows that the spectra are nearly-identical to each other (Figure 1e). Therefore, we conclude that the negative charge is exclusively located on the uracil base in Urd and UMP (U•−MP and U•−rd). Moreover, the observed increase of anion radical signal (blue curve in Figure 1e, Figure 2e) is correlated with the decay of ehyd−, which also verifies this finding. At longer timescales (8 ns, Figure 1b), all anion radicals including U•−MP, U•−rd and U•−, are found to remain stable at least within the detection time window. Thus, these results show that neither the intramolecular electron transfer from the uracil base to other subunits (sugar and phosphate) nor intermolecular transfer to neighboring UMP occurs.

[U•−MP]* formed by epre− attachment to UMP can either relax to its ground state which is of the same nature as the U•−MP formed via the reaction with ehyd−, or it can dissociate into fragments. Correlation of the amount of epre− captured by UMP with the initial yield of U•−MP indicates that the dissociation channel is not an efficient process and that epre− and ehyd− attachment lead to the same radical products, which is in agreement with our previous observations for guanine monophosphate in water.12 Taking into account of the experimentally determined rate constant of epre− attachment (~5×1012 M−1·s−1) to UMP, the dissociation does not take place because UMP would not be able to scavenge the electrons at higher energy level, such as non-thermalized electrons (time constant of thermalization <30 fs)11,17 even at concentrations as high as 1 M.

When the ultrafast formation of [UMP]•+ occurs the positive charge is likely to be statistically distributed over different parts of the molecules: uracil, ribose and phosphate. The positive charge localized on phosphate subunit, UMP•+, has been found to follow a nearly first order decay with a time constant of ca. 2.5 ns. From the comprehensive one-electron oxidation experiments of UMP, Urd, U and ribose, it was learned that initially the uracil base moiety has the lowest redox potential to trap the holes.18–22 However, through a rapid base-to-sugar charge transfer process happening in a conformation of UMP in which the sugar-phosphate very proximate to the base cation radical, the holes are eventually trapped in the backbone (Figure SI5).23 Thus, the decay is likely to be an intramolecular or intermolecular electron transfer process. The intermolecular pathway is excluded because the model study of bimolecular reaction between H2PO4• and ribose in highly acidic condition of H3PO4 solutions (Figure SI4) shows this reaction occurs on microsecond timescale (for details see SI), indicating that the R unit of UMP repairs P•+. Furthermore, the temperature effect (Figure SI4) on the hole transfer process did not show noticeable impact on the lifetime and decay rate of UMP•+ up to 60°C. This experimental result indicates that the activation barrier of this hole transfer process is negligible. In aqueous solutions, deprotonation and hydration of the UMP cation radical will cause the formation of other transients, such as, 6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrouracil-5yl.24 In addition, oxygen will play a significant role on the fate of UMP radicals.25 However, in our experiments in sub- and nanosecond time ranges, these reactions and other conversions of UMP-radicals are less likely owing to the rates of these reactions1; only the ultrafast reactions, such as, electron attachment and charge transfer processes from different sites (base-to-sugar, phosphate-to-sugar etc.) in a single nucleotide are the predominant processes. In fact, our studies identify the radicals which would undergo these reactions, e.g., deprotonation, hydration, reaction with oxygen etc.

Carbon-centered radicals located on the 2′-deoxyribose moiety are likely attributed to the precursors of radiation-induced strand breaks1,3, so tracking the sugar radical formation in DNA is of crucial importance to the biological consequences of radiation3,26,27. The mechanism of formation of neutral sugar radicals is dominated by the fast deprotonation of sugar cation radicals as a result of very rapid base-to-sugar hole transfer28 or phosphate-to-sugar hole transfer.18–20 Hence, the decay of URP•+ observed in UMP as well as H2PO4• in H3PO4 / ribose solutions provides evidence for the rates of phosphate-to-sugar hole transfer process and subsequent deprotonation of the incipient sugar cation radical. Using concentrated UMP solutions, we were not able to observe the expected increase of absorption due to sugar cation radical by transient absorption spectroscopy because of high UV absorption (< 350 nm) of UMP solute itself. On this basis, we consider that the hole in irradiated aqueous Urd should be formed and trapped on the sugar moiety as well as on the uracil ring. This is because the irradiated medium has an electron fraction similar to the corresponding one found in UMP. However, even at a higher concentration of Urd (1.5 M) that is comparable to UMP (1.2 M), no transient signal of U•+rd was detected (Figure 2). Thus, from the absence of signal due to [Urd]•+ absorption (Figure S5), we conclude that in [Urd]•+, there occurs a very facile intramolecular charge transfer from base-to-sugar within a picosecond time window and most likely via a tunneling process similar to that found in UMP23 and in one-electron oxidized gemcitabine.28 The fate of directly formed UR•+P radical (Scheme 1) is difficult to track due to previously-mentioned issues with high concentrations. Moreover, pulse radiolysis experiments with ribose 5-phosphate (RP) did not succeed, since RP was rapidly degrading under radiation. Accounting for the phosphate-to-sugar hole transfer process, we consider that once formed, UR•+P, remains stable within tens of nanoseconds.

Scheme 1.

Main radiolysis pathways of UMP water solutions.

In conclusion, this picosecond pulse radiolysis study of rapid charge localization in UMP via electron-irradiation of its aqueous solution has led to the following salient findings (Scheme 1 and Table S1). 1) UMP effectively scavenges epre− and ehyd− thereby forming the corresponding anion radicals, [UMP]*•− and [UMP]•−, with electron localization on the pyrimidine base ring, without leading to the dissociation of UMP. 2) The ionization of UMP takes place via direct ionization and the reaction of UMP with H2O•+, leading to the formation of [UMP]•+, whereas the positive charge is statistically distributed over the different parts of the molecule. The hole will eventually localize on the ribose, and the hole transfer path from phosphate to ribose occurs as a rather slow intramolecular process, possible assisted by H-atom transfer with a negligible activation barrier;21,22 the path from uracil to ribose occurs in ultrafast regime. Our observation explains why, ESR studies of irradiated DNA18–20,28, or models (e.g., dimethyl phosphate19) of sugar-phosphate backbone, the phosphate radical was not observed. 3) Our work has provided an experimental estimate of the extent of direct-type effect occurring in an aqueous phase at ambient condition. It is known that the sugar radicals are precursors of DNA strand breaks and crosslinking.1–6 Thus, the successful application of a picosecond pulse radiolysis technique on aqueous DNA/RNA-model systems paves the way to solve the long-standing mysteries in the earliest events of radiation-induced damage to nucleic acids (DNA/RNA).

Experimental section

The chemical compounds (5′-UMP in the form of disodium salts, Urd, uracil and ribose; purity, >99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were used without further purification. The 5 ps picosecond pulse radiolysis transient absorbance measurements were performed at the electron facility ELYSE29 (Université Paris Sud, France), coupled with transient absorption broadband probe spectroscopy (360–800 nm for timescales <10 ns, 250 – 850 nm for timescales >10 ns, see SI for details). The spectra of the absorbing species in the type of system studied here are known to strongly overlap; as a result, it becomes difficult to deconvolute individual spectra. Therefore, a global data analysis approach was used by using SK-Ana code.30

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

JM thanks Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) funding for support. AA thanks the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01CA045424) for support. AA is also grateful to Research Excellence Fund (REF) and Center for Biomedical Research (CBR) at Oakland University for support.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Extra information on experimental methods are available, extra experimental data discussing electron scavenging, phosphate radical reduction by ribose, and single electron oxidation of UMP, Urd, U by sulfate anion radical (SO4•−).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sonntag C Free-Radical-Induced DNA Damage and Its Repair: A Chemical Perspective; SpringerLink: Springer e-Books; Springer; Berlin Heidelberg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sevilla MD; Bernhard WA Mechanisms of Direct Radiation Damage to DNA In Radiation Chemistry. From Basics to Applications in Material and Life Science; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Adhikary A; Becker D; Sevilla MD Electron Spin Resonance of Radicals in Irradiated DNA BT - Applications of EPR in Radiation Research; Lund A, Shiotani M, Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp 299–352. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ward JF The Complexity of DNA Damage: Relevance to Biological Consequences. Int. J. Radiat. Biol 1994, 66, 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bernhard WA; Close DM DNA Damage Dictates the Biological Consequences of Ionizing Radiation: The Chemical Pathways In Charge Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter; Hatano Y, Mozumder A, Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2004; pp 431–470. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Purkavastha S; Milligan JK; Bernhard WA Correlation of Free Radical Yields with Strand Break Yields Produced in Plasmid DNA by the Direct Effect of Ionizing Radiation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 16967–16973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Boudaïffa B; Cloutier P; Hunting D; Huels MA; Sanche L Resonant Formation of DNA Strand Breaks by Low-Energy (3 to 20 EV) Electrons. Science 2000, 287, 1658–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Alizadeh E; Sanche L Precursors of Solvated Electrons in Radiobiological Physics and Chemistry. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 5578–5602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Becker D; Adhikary A; Sevilla MD Mechanisms of Radiation-Induced DNA Damage: Direct Effects In Recent trends in radiation chemistry; World Scientific, 2010; pp 509–542. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hancock R The Nucleus: Volume 1: Nuclei and Subnuclear Components; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Migus A; Gauduel Y; Martin JL; Antonetti A Excess Electrons in Liquid Water: First Evidence of a Prehydrated State with Femtosecond Lifetime. Phys. Rev. Lett 1987, 58, 1559–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ma J; Wang F; Denisov SA; Adhikary A; Mostafavi M Reactivity of Prehydrated Electrons toward Nucleobases and Nucleotides in Aqueous Solution. Sci. Adv 2017, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ma J; Schmidhammer U; Pernot P; Mostafavi M Reactivity of the Strongest Oxidizing Species in Aqueous Solutions: The Short-Lived Radical Cation H2O+. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2014, 5, 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ma J; Schmidhammer U; Mostafavi M Picosecond Pulse Radiolysis of Highly Concentrated Phosphoric Acid Solutions: Mechanism of Phosphate Radical Formation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 7180–7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yamagami R; Kobayashi K; Tagawa S Formation of Spectral Intermediate G-C and A-T Anion Complex in Duplex DNA Studied by Pulse Radiolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 14772–14777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ma J; Marignier J-L; Pernot P; Houee-Levin C; Kumar A; Sevilla MD; Adhikary A; Mostafavi M Direct Observation of the Oxidation of DNA Bases by Phosphate Radicals Formed under Radiation: A Model of the Backbone-to-Base Hole Transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2018, 20, 14927–14937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Stahler J; Deinert JC; Wegkamp D; Hagen S; Wolf M Real-Time Measurement of the Vertical Binding Energy during the Birth of a Solvated Electron. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 3520–3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Adhikary A; Kumar A; Palmer BJ; Todd AD; Sevilla MD Formation of S-Cl Phosphorothioate Adduct Radicals in DsDNA S-Oligomers: Hole Transfer to Guanine vs Disulfide Anion Radical Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 12827–12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Adhikary A; Becker D; Palmer BJ; Heizer AN; Sevilla MD Direct Formation of the C5′-Radical in the Sugar-Phosphate Backbone of DNA by High Energy Radiation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 116, 5900–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Shukla LI; Pazdro R; Becker D; Sevilla MD Sugar Radicals in DNA: Isolation of Neutral Radicals in Gamma-Irradiated DNA by Hole and Electron Scavenging. Radiat. Res 2005, 163, 591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gutsev GL; Ampadu Boateng D; Jena P; Tibbetts KM A Theoretical and Mass Spectrometry Study of Dimethyl Methylphosphonate: New Isomers and Cation Decay Channels in an Intense Femtosecond Laser Field. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 8414–8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Steenken S; Goldbergerova L Photoionization of Organic Phosphates by 193 Nm Laser Light in Aqueous Solution: Rapid Intramolecular H-Transfer to the Primarily Formed Phosphate Radical. A Model for Ionization-Induced Chain-Breakage in DNA? J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 3928–3934. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hildenbrand K The SO4- Induced Oxidation of 2′-Deoxyuridine-5′-Phosphate, Uridine-5′-Phosphate and Thymidine-5′-Phosphate. An ESR Study in Aqueous Solution. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1990, pp 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Cadet J; Davies KJA Oxidative DNA Damage & Repair: An Introduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2017, 107, 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Deeble DJ; Sonntag CVON Radioprotection of Pyrimidines by Oxygen and Sensitization by Phosphate: A Feature of Their Electron. 1987, No. reaction 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Greenberg MM Elucidating DNA Damage and Repair Processes by Independently Generating Reactive and Metastable Intermediates. Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ward JF Complexity of Damage Produced by Ionizing Radiation. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 2000, 65, 377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Adhikary A; Kumar A; Rayala R; Hindi RM; Adhikary A; Wnuk SF; Sevilla MD One-Electron Oxidation of Gemcitabine and Analogs: Mechanism of Formation of C3 and C2 Sugar Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 15646–15653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Belloni J; Monard H; Gobert F; Larbre JP; Demarque a.; De Waele V; Lampre I; Marignier JL; Mostafavi M; Bourdon JC; et al. ELYSE - A Picosecond Electron Accelerator for Pulse Radiolysis Research. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip 2005, 539, 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ruckebusch C; Sliwa M; Pernot P; de Juan A; Tauler R Comprehensive Data Analysis of Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectra: A Review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev 2012, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.