Abstract

Weight concerns are common among adolescents and are associated with a range of negative psychological and physical health outcomes. Self-esteem is one correlate of weight concerns, yet prospective research has not yet documented the direction of this association over the course of adolescence or whether this association differs by gender. This study sought to clarify the role of self-esteem in the development of adolescents’ weight concerns and investigate the potentially protective role of father and mother responsiveness, another documented correlate of weight concerns. Participants were 392 predominately Caucasian/European American adolescents, ages 11–18, and their parents. Time lagged mixed effects models revealed bidirectional associations between self-esteem and weight concerns at the within-individual level over the course of adolescence. Results also confirmed the moderating roles of youth gender and father responsiveness in the prospective link between self-esteem and weight concerns such that father responsiveness buffered the effects of low self-esteem on weight concerns for girls but not boys. Only gender moderated the prospective link between weight concerns and self-esteem: On occasions when youth reported higher self-esteem than usual (compared to their own cross-time average) they reported fewer weight concerns the next year, but this effect was slightly larger for boys. Findings suggest that self-esteem and weight concerns are reciprocally related in adolescence and highlight the importance of examining interactions between family processes and individual characteristics to predict adolescent psychological adjustment.

Keywords: adolescence, self-esteem, weight concerns, parent responsiveness, family systems

Weight concerns include fear of weight gain, preoccupation with body shape and weight, perception of overweight, and weight loss behaviors (Killen et al., 1994). The prevalence of weight concerns among youth has reached alarming rates, with 34% of adolescent girls and 21% of adolescent boys endorsing concerns or distress about their weight (Micali, Ploubidis, De Stavola, Simonoff, & Treasure, 2014). Girls are disproportionately affected by weight concerns, and this trend persists over time: Girls’ weight concerns increase over adolescence, whereas boys’ show little change (Lam & McHale, 2012). Importantly, weight concerns predict onset of eating disorders and are associated with depression, low self-esteem, risky behaviors, and losses in quality of life, social, emotional, and physical functioning among adolescents (Farhat, Iannotti, & Summersett-Ringgold, 2015, Killen et al., 1994; McHale, Corneal, & Crouter, 2001). Given these detrimental impacts, research is needed to identify risk and protective factors that prevent the onset or mitigate the severity of adolescents’ weight concerns. Few putative risk factors have received adequate empirical support from prospective designs, however, and those that have been identified were not strong predictors of eating pathology (Stice, 2002). Longitudinal research is a crucial step in developing an etiologic model of weight concern development and informing the design of interventions (Kraemer et al., 1997).

Toward identifying risk and protective factors for the development of weight concerns, this study used longitudinal data to establish the temporal relations between self-esteem and weight concerns. We also tested gender as a moderator of these associations because self-esteem and weight concerns have different developmental trajectories for girls and boys, with girls experiencing greater increases in weight concerns and decreases in self-esteem compared to boys during adolescence (Lam & McHale, 2012; Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005). We used a sample ranging in age from early to late adolescence because we lacked empirically guided expectations for when during adolescence this association might be apparent. Our study also was grounded in the idea that development is shaped through reciprocal transactions between individuals and other family members, including parents. These interactions are not static, underscoring the importance of examining family relationships over time and how fluctuations in adolescents’ characteristics, such as self-esteem and weight concerns, may be driven by changing family experiences (Davies & Cicchetti, 2004). To better understand the role of family processes, we examined the role of parent responsiveness as a protective factor for weight concerns.

Prior work suggests that dimensions of parental responsiveness, including acceptance and support, may mitigate youth weight concerns. For example, longitudinal studies (Lam & McHale, 2012; May, Kim, McHale, & Crouter, 2006) indicate that lower levels of maternal, but not paternal, intimacy and knowledge are associated with more weight concerns in adolescent girls, and on occasions when youth report lower levels of maternal acceptance or higher levels of father-adolescent conflict than usual, they report more weight concerns the following year. Similarly, cross-sectional studies indicate that parental hostility and lack of support are associated with youth weight concerns (Ata, Ludden, & Lally, 2007; Hochgraf, Kahn, & Kim-Spoon, 2017).

One component of adolescent psychological adjustment that may play a role in the development and maintenance of weight concerns is self-esteem, a person’s overall feelings of worth. Self-esteem theory emphasizes the roles of individuals’ feelings of competence in domains that are important to them and others’ appraisals of their worth (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001; Harter, 1993). Thus, in individuals for whom physical appearance is important, negative evaluations of their bodies should lead to lower self-esteem. As self-esteem is also shaped by the opinions of significant others, perceptions that family members have judged them as unworthy should result in lower self-esteem (Harter, 1993). This tenet is particularly relevant to the connections between parent responsiveness, self-esteem, and weight concerns. Adolescents’ overvaluation of physical appearance and parents’ lack of responsiveness could both lead to low self-esteem. However, low self-esteem derived from failure to meet ideals of attractiveness could be buffered by responsive parents. Indeed, there is evidence that adolescents’ perceptions of maternal and paternal supportiveness predict their self-esteem (Gecas & Schwalbe, 1986).

Few studies have investigated links between adolescent self-esteem and weight concerns, and we found none that evaluated temporal precedence. Most work on self-esteem and eating disorder development has focused on body dissatisfaction, a related but distinct construct from weight concerns. Body dissatisfaction indicates discontent with body shape and size (Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983) whereas weight concerns capture psychological and behavioral characteristics of individuals with eating disorders (Killen et al., 1994; Gordon, Holm-Denoma, Crosby, & Wonderlich, 2010). Prospective, longitudinal analyses of self-esteem and body dissatisfaction may illuminate directions of effects between weight concerns and self-esteem.

Studies of adolescents suggest that body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts self-esteem, and typically body dissatisfaction is higher and self-esteem is lower among girls than boys (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., 2015; Paxton, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2006). Other work suggests, however, that self-esteem predicts body dissatisfaction for girls but not boys (Paxton, et al., 2006). Wichstrom and von Soest (2016) found bidirectional associations between self-esteem and body dissatisfaction. Together, these findings suggest a possible bidirectional link between weight concerns and self-esteem that may differ by gender.

In sum, research highlights that: (a) parent responsiveness is associated with higher self-esteem and fewer weight concerns, (b) the link between self-esteem and weight concerns may be bidirectional, and (c) these effects may differ by youth gender. Together these findings suggest a feedback loop linking self-esteem and weight concerns during adolescence, such that low self-esteem predicts higher weight concerns, which in turn predict lower self-esteem. Parent responsiveness may interrupt this cycle, leading to fewer weight concerns by augmenting adolescents’ self-esteem and/or by buffering effects of low self-esteem. As boys’ and girls’ developmental trajectories for self-esteem and weight concerns differ and prior work suggests differential patterns of association for boys and girls (Lam & McHale, 2012; Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005), this model may be applicable to girls more so than boys.

We tested this model by measuring the directions of associations between self-esteem and weight concerns across adolescence and the roles of parent responsiveness and gender in these linkages. As fathers’ roles in the development of weight concerns are not well understood, adolescents’ perceptions of father and mother responsiveness were included as separate variables in the same model. First, we hypothesized negative, bidirectional relations between self-esteem and weight concerns. Second, we expected higher levels of responsiveness from either parent to buffer the effects of low self-esteem on weight concerns and weight concerns on self-esteem. Third, we hypothesized youth gender would interact with self-esteem and weight concerns such that girls would exhibit stronger links between self-esteem and weight concerns than boys.

Method

Participants and Study Procedures

Participants were 392 adolescents ages 11–18 (mean age at first measurement = 15 years, SD = 1.63; 49.5% female) and their mothers and fathers from 196 families who were part of a longitudinal study of development and family relationships that began in 1995–1996. Eligibility criteria were that parents were married and employed and that their firstborn child was in 4th or 5th grade with a sibling 1–4 years younger. Retention was 97% during the years used in this study; of the 203 original families, five withdrew from the study in earlier years and two did not participate in the years used for this analysis. This study used self-report data from both youth in each family and demographic data collected from parents in Years 6, 8, and 9 via home interviews, when both siblings were adolescents. Year 7 was not included because weight concerns were not measured. Hereafter, Years 6, 8, and 9 are referred to as Times 1, 2, and 3. The sample was almost exclusively Caucasian, which is representative of the region. However, the sample was slightly more educated than typical adults of the region: Mothers’ mean education was 14.78 (SD = 2.18), and fathers, 14.84 (SD = 2.45) of on a scale where 12 = high school degree, 14 = some college, and 16 = bachelor’s degree, whereas median adult education in the state was a high school degree/12 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005). Mean annual family income at Time 1 was $38,552 (SD = $18,011, range = $0–101,500) whereas median income for the region was $43,426 (DeNavas-Walt, Cleveland, & U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). Participants provided informed consent/assent and the IRB approved all study procedures.

Measures

Adolescents completed the 6-item Stanford Weight Concerns Scale (Killen et al., 1994) at Times 1, 2, and 3. Cronbach alphas ranged from .77 to .86. They also rated mother and father responsiveness at Times 1, 2, and 3 using a five-item scale from the Parenting Style Inventory (Darling & Toyokawa, 1997). Cronbach alphas ranged from .76 to .85. Finally, adolescents reported their self-esteem at Times 1, 2, and 3 using the five-item Self-Worth subscale of Harter’s Perceived Competence Scale (Harter, 1988). Self-esteem and self-worth are considered to be the same construct (Harter, 1993). Cronbach alphas ranged from .83 to .85.

Adolescents’ reports of height and weight collected at Time 1 were used to calculate BMI (M = 21.14, SD = 3.71, range = 12.96–36.87), as prior research indicates this method is accurate for adolescent girls and boys (Clarke, Sastry, Duffy, & Ailshire, 2014). Mothers’ report of their children’s ages was included as a control because weight concerns and self-esteem change across development (Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005). Mothers’ and fathers’ Time 1 levels of education were correlated, r = .49, p < .001 and thus averaged to reflect socioeconomic status. (M = 14.81, SD = 2.00, range = 11.50–20.00). Mothers reported youth gender.

Analysis Plan

Multilevel modeling was used to accommodate the clustered (i.e., siblings within families with repeated measurements across three time points) and unbalanced (i.e., time intervals between years of measurement varied) study design. A time-lagged design allowed for testing within-person changes over time while controlling for each person’s cross time average. Using this approach, we estimated residual change from year to year in the dependent variables that was explained by the predictor variables, controlling for the dependent variables in the prior year, a rigorous test of association that illuminates directions of effects between self-esteem and weight concerns and interactions with youth gender and mother and father responsiveness.

Two-level random intercept models were estimated using the MIXED procedure in SAS (9.4). Heterogeneous compound symmetry was used to adjust for the non-independence of residuals between siblings, and restricted maximum likelihood estimation accommodated missing observations (130 missing observations in Model 1 and one in Model 2). Model 1 (“Weight Concerns”) tested the main effect of self-esteem and two- and three-way interactions between gender, parent responsiveness, and self-esteem in predicting weight concerns. Model 2 (“Self-Esteem”) tested the main effect of weight concerns and the two- and three-way interactions between gender, parent responsiveness and weight concerns in predicting self-esteem. In both models, predictors were lagged within-person levels of the independent variables the previous year, and between-person variables were the participants’ cross time averages of the independent variables. Between-person variables and time invariant controls were centered on the grand mean, and lagged predictors were person-centered. At Level 2, time invariant predictors were entered, including parent education, BMI, gender, and the cross time averages of mother and father responsiveness as well as the cross time average of self-esteem (Model 1) and weight concerns (Model 2). At Level 1, the time varying predictors were entered (age, lagged weight concerns, lagged self-esteem, and lagged father and mother responsiveness). Including youth’s cross time averages of predictors at Level 2 made it possible to test whether residual change across years predicted change in the dependent variable beyond adolescents’ average level of the predictors. The lagged versions of the dependent variables (i.e., weight concerns in Model 1; self-esteem in Model 2) were included to control for prior levels of the dependent variables. For both Model 1 and 2, an empty model, a main effects model, and then a two- and three-way interaction model were estimated. See Supplementary Material for more information on model estimation, equations, and descriptives.

Results

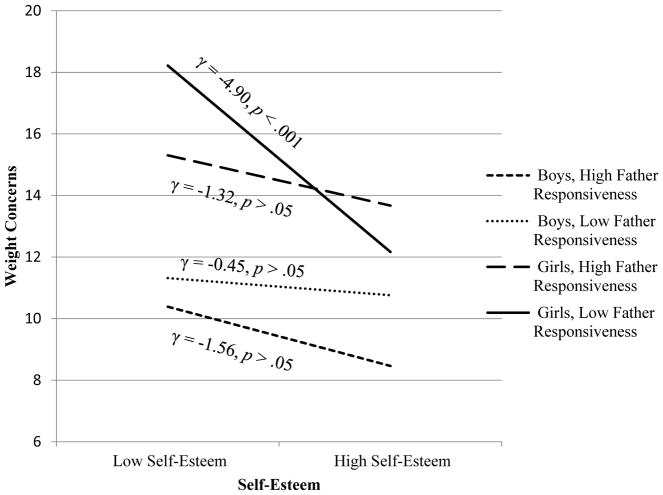

For Model 1 (Table 1), the control variables age, BMI, weight concerns the previous year, and participants’ cross time average of self-esteem were significant predictors of weight concerns. Beyond these, adolescent self-esteem was a significant negative predictor of weight concerns, such that higher self-esteem than usual (relative to the adolescent’s cross time average) predicted lower than usual weight concerns the following year. Neither mother nor father responsiveness predicted weight concerns the following year. A gender main effect revealed that girls reported significantly more weight concerns than boys but neither the two-way interaction between gender and self-esteem nor the two-way interactions between gender and mother or father responsiveness were significant. The two-way interaction between self-esteem and father but not mother responsiveness, was statistically significant, but was qualified by a three-way, self-esteem X father responsiveness X gender interaction. When probed at one standard deviation above and below the mean of adolescent self-esteem, only the simple slope for girls with low father responsiveness was statistically significant, γ = −4.90, p < .001: For these girls, every one unit decrease in self-esteem meant a 4.9 unit increase in weight concerns (Figure 1). For Model 2 (Table 2), self-esteem the previous year and participants’ cross time average of weight concerns were the only control variables that predicted self-esteem the following year. Lagged weight concerns negatively predicted self-esteem, such that higher weight concerns than usual predicted lower self-esteem the following year. Mother, but not father, responsiveness also predicted self-esteem: On occasions when mother responsiveness was higher than usual, youth’s self-esteem the following year was also higher than usual. One interaction emerged between gender and lagged weight concerns. When probed at one standard deviation above and below the mean of weight concerns, the prospective, within-individual association between self-esteem and weight concerns was significant for boys and girls, but the slope was steeper for boys, γ = −0.04, p < .001, than girls, γ = −0.02, p < .05.

Table 1.

Model 1: The Prospective Link between Self-Esteem and Weight Concerns

| Main Effects | Two Way Interactions | Full Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | t -value | γ | t -value | γ | t -value | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 15.19*** | 26.43 | 15.19*** | 26.43 | 14.84*** | 25.21 |

| Age (γ10) | 0.44* | 2.31 | 0.44* | 2.31 | 0.47* | 2.47 |

| Body Mass Index (γ02) | 0.31*** | 3.89 | 0.31*** | 3.89 | 0.32*** | 4.05 |

| Gender (γ01) | −4.77*** | −6.19 | −4.77*** | −6.19 | −4.61*** | −5.85 |

| Parent Education (γ03) | --- | --- | ||||

| WCt-1 (γ30) | −0.57*** | −7.92 | −0.57*** | −7.92 | −0.54*** | −7.87 |

| SEBP (γ04) | −2.15** | −2.71 | −2.15** | −2.71 | −2.07* | −2.70 |

| FRBP (γ05) | −0.11 | −0.71 | −0.11 | −0.71 | −0.15 | −1.02 |

| MRBP (γ06) | −0.11 | −0.53 | −0.11 | −0.53 | −0.08 | −0.38 |

| SE t-1 (γ20) | −2.82*** | −5.68 | −2.82*** | −5.68 | −3.11*** | −5.71 |

| FR t-1 (γ40) | −0.18* | −1.81 | −0.18* | −1.81 | −0.11 | −0.94 |

| MR t-1 (γ50) | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| Gender* SE t-1 (γ21) | --- | --- | 2.11 | 1.89 | ||

| SE t-1* FR t-1 (γ70) | --- | --- | 0.54*** | 4.12 | ||

| SE t-1* MR t-1 (γ60) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Gender* FR t-1 (γ41) | --- | --- | −0.14 | −0.75 | ||

| Gender* MR t-1 (γ51) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Gender* SE t-1* FR t-1 (γ71) | −0.70* | −2.81 | ||||

| Gender* SE t-1* MR t-1 (γ61) | --- | --- | ||||

Note. t-1 = lagged; BP = cross time average; WC = weight concerns; SE = self-esteem; FR = father responsiveness; MR = mother responsiveness.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Three-way interaction of self-esteem and father responsiveness in predicting weight concerns of girls and boys

Table 2.

Model 2: The Prospective Link between Weight Concerns and Self-Esteem

| Main Effects | Two Way Interactions | Full Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | t -value | γ | t -value | γ | t -value | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 3.19*** | 64.65 | 3.17*** | 62.92 | 3.17*** | 62.92 |

| Age (γ10) | --- | --- | ||||

| Body Mass Index (γ02) | --- | --- | ||||

| Gender (γ01) | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Parent Education (γ03) | --- | --- | ||||

| SE t-1 (γ20) | −0.54*** | −7.98 | −0.54*** | −8.01 | −0.54*** | −8.01 |

| WCBP (γ04) | −0.03*** | −4.11 | −0.03*** | −4.08 | −0.03*** | −4.08 |

| FRBP (γ05) | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| MRBP (γ06) | 0.03 | 1.43 | 0.03 | 1.62 | 0.03 | 1.62 |

| WC t-1 (γ30) | −0.02*** | −4.22 | −0.02* | −2.75 | −0.02* | −2.75 |

| FR t-1 (γ40) | 0.02 | 1.54 | 0.01 | 1.44 | 0.01 | 1.44 |

| MR t-1 (γ50) | 0.04** | 3.29 | 0.04** | 3.48 | 0.04** | 3.48 |

| Gender* WC t-1 (γ31) | −0.02* | −2.14 | −0.02* | −2.14 | ||

| WC t-1* FR t-1 (γ70) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| WC t-1* MR t-1 (γ60) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Gender* FR t-1 (γ41) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Gender* MR t-1 (γ51) | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Gender* WC t-1* FR t-1 (γ71) | --- | --- | ||||

| Gender* WC t-1* MR t-1 (γ61) | --- | --- | ||||

Note. t-1 = lagged; BP = cross time average; SE = self-esteem; WC = weight concerns; FR = father responsiveness; MR = mother responsiveness.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Discussion

We found support for a new conceptual model of the development of weight concerns during adolescence: Hypothesized bidirectional links between self-esteem and weight concerns indicated that higher self-esteem than usual (relative to the adolescent’s cross time average) predicted lower weight concerns than usual the following year, and more weight concerns than usual predicted lower self-esteem than usual the following year. These within-person associations were observed after controlling for participants’ cross time averages of the predictor variables, meaning that the results cannot be attributed to stable individual differences (Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002). These bidirectional links provide support for a feedback loop linking self-esteem and weight concerns during adolescence.

There was also evidence that parent responsiveness acts as a protective factor to interrupt this cycle, leading to fewer weight concerns by augmenting adolescents’ self-esteem and by buffering effects of low self-esteem. Specifically, father responsiveness moderated the prospective link between self-esteem and weight concerns for girls, and higher than usual mother responsiveness predicted adolescents’ self-esteem the following year. The proposed model described girls better than boys with the exception that both boys’ and girls’ self-esteem benefitted from maternal responsiveness. These findings advance understanding of the family contexts of the development of weight concerns by documenting that weight concerns may both influence and be influenced by adolescents’ self-esteem and the protective role of parent responsiveness. These bidirectional associations are consistent with self-esteem theories, which suggest that adolescents who overvalue physical appearance will experience declines in self-esteem when they have negative evaluations of their bodies. However, self-esteem theories do not account for the prospective link between self-esteem and weight concerns, suggesting that an alternate theory, such as the proposed model’s feedback loop between self-esteem and weight concerns, is needed to describe this reciprocal association.

The moderating role of gender in the bidirectional link between self-esteem and weight concerns is consistent with gender differences in developmental trajectories of self-esteem and weight concerns (Lam & McHale, 2012; Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005) and prior research suggesting the link between self-esteem and body dissatisfaction is apparent for girls but not boys (Paxton et al., 2006). Although both girls’ and boys’ weight concerns predicted self-esteem, boys’ weight concerns were significantly lower and boys’ self-esteem was higher than girls’. Thus, although a one-unit increase in weight concerns corresponded to a slightly greater decrease in self-esteem for boys girls, girls still experienced more weight concerns and lower self-esteem overall. This finding suggests that appearance informs both boys’ and girls’ self-esteem, but perhaps girls’ more so, consistent with gender socialization theories and findings that girls value a desirable body weight more so than boys (Clabaugh, Karpinski, & Griffin, 2008).

Gender socialization processes may also explain the differential influence of mother and father responsiveness in self-esteem-weight concern linkages. Gender socialization theory suggests that both parent and child gender shape parent-child interactions: Mother-child relationships are closer and are characterized by more responsiveness and disagreements than father-child relationships (McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003). Thus, mothers’ responsiveness may be more relevant for adolescents’ self-esteem. Only fathers’ responsiveness had a buffering effect on the prospective link between low self-esteem and weight concerns, and only for daughters. Fathers’ responsiveness may be a point of reference for girls during adolescence as girls navigate relationships with the other sex and develop attitudes toward their bodies. Together, these results are consistent with the idea that mothers’ responsiveness has effects on a global domain of adjustment (i.e., self-esteem), whereas fathers’ responsiveness has effects on a specific domain for their children with a risk characteristic (i.e., gender).

These findings have implications for preventing weight concerns. Existing programs (e.g., The Body Project) are individual-focused (Stice, Rohde, & Shaw, 2013) and do not consider family processes such as parent responsiveness as targets for prevention. This study provided evidence that increasing mother and father responsiveness may reduce adolescents’ weight concerns. Thus, targeting family processes, particularly parent responsiveness, may bolster intervention effect sizes. Existing family-centered prevention programs for risky behaviors during adolescence (e.g., Family Check-Up) foster parent responsiveness, but program evaluations have yet to include weight concerns (Gill, Dishion, & Shaw, 2014). Thus, there are opportunities to develop family-centered eating disorder prevention programs and assess the impact of existing family-centered programs on weight concerns.

Our findings prompt further research. Given variation in body ideals, eating behaviors, and parenting behaviors across ethnic groups, replication in diverse samples is warranted. In addition, although the longitudinal, lagged design permits inferences about the direction of association, causality cannot be inferred. Research using more closely spaced measurements may illuminate the time in development when bidirectional links between self-esteem and weight concerns emerge. Studies should also incorporate objective measurements of BMI. Finally, research should determine whether parent responsiveness is consistently protective throughout adolescence. As adolescents spend considerable amounts of time with their peers, it will be important to examine whether peer evaluations of adolescents’ worth are similarly protective to self-esteem and weight concerns.

Although many questions remain, this study advanced understanding of the development of weight concerns and self-esteem during adolescence and the role of mothers and fathers in adolescents’ psychological adjustment. Findings underscore the need to consider how family processes interact with individual characteristics to influence risk for weight concerns. Identifying modifiable risk and protective factors, such as parent responsiveness and self-esteem, and uncovering how these factors differentially affect youth will refine theories of eating disorder development and may enhance effectiveness of prevention programs.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ata RN, Ludden AB, Lally MM. The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:1024–1037. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clabaugh A, Karpinski A, Griffin K. Body weight contingency of self-worth. Self and Identity. 2008;7:337–359. doi: 10.1080/15298860701665032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Sastry N, Duffy D, Ailshire J. Accuracy of self-reported versus measured weight over adolescence and young adulthood: findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health, 1996–2008. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;180:153–159. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Wolfe CT. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review. 2001;108:593–623. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Toyokawa T. Construction and validation of the parenting style inventory II (PSI-II) 1997 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cicchetti D. Toward an integration of family systems and developmental psychopathology approaches. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:477–481. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Cleveland R USCensus Bureau. Money income in the United States: 2001. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat T, Iannotti RJ, Summersett-Ringgold F. Weight, weight perceptions and health-related quality of life among a national sample of US girls. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2015;36:313. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, McCabe M, Skouteris H, Richardson B, Nihill K, Watson B, Solomon D. Does body satisfaction influence self-esteem in adolescents’ daily lives? An experience sampling study. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;45:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1983;2:15–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15::AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gecas V, Schwalbe ML. Parental behavior and adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:37–46. doi: 10.2307/352226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AM, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS. The Family Check-Up. In: Landry SH, Cooper CL, editors. Wellbeing in children and families. West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2014. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KH, Holm-Denoma JM, Crosby R, Wonderlich SA. The Oxford Handbook of Eating Disorders. New York: Oxford; 2010. The classification of eating disorders; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Denver: U. of Denver; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In: Baumeister RF, editor. Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard. Springer; 1993. pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hochgraf AK, Kahn RE, Kim-Spoon J. The moderating role of emotional reactivity in the link between parental hostility and eating disorder symptoms in early adolescence. Eating Disorders. 2017;25:420–435. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2017.1347417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JE, Lanza S, Osgood DW, Eccles JS, Wigfield A. Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one though twelve. Child Development. 2002;73:509–527. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, Wilson DM, Haydel KF, Hammer LD, … Kraemer H. Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: A three-year prospective analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:227–238. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199411)16:3<227::AID-EAT2260160303>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of general psychiatry. 1997;54:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM. Developmental patterns and family predictors of adolescent weight concerns: A replication and extension. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:524–530. doi: 10.1002/eat.20974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May AL, Kim JY, McHale SM, Crouter A. Parent–adolescent relationships and the development of weight concerns from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:729–740. doi: 10.1002/eat.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Corneal DA, Crouter AC, Birch LL. Gender and weight concerns in early and middle adolescence: Links with well-being and family characteristics. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:338–348. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Whiteman SD. The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2003;12:125–148. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micali N, Ploubidis G, De Stavola B, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Frequency and patterns of eating disorder symptoms in early adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: a five-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:888–899. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME. Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:539–549. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH. Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:825. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H. The Body Project: A dissonance-based eating disorder prevention intervention. New York, NY: Oxford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M. Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self-esteem: Prospective findings. Body Image. 2005;2:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Educational attainment by employment status for the population 25 to 64 years. 2005 Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/

- Wichstrøm L, von Soest T. Reciprocal relations between body satisfaction and self-esteem: A large 13-year prospective study of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2016;47:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.