Abstract

Objective.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) is conceptualized as a disorder of negative affect and low effortful control. Yet, empirical tests of trait associations with ODD remain limited. The current study examined the relationship between temperament and personality traits and DSM-5 ODD symptom domains and related impairment in a preschool-aged sample.

Method.

Participants were 109 children ages 3–6 (59% male), over-recruited for ODD from the community, and their primary caregivers (87% mothers). ODD symptoms and impairment were measured using the Kiddie-Disruptive Behavior Disorder Schedule, temperament traits were measured using parent report on the Child Behavior Questionnaire and the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, and personality traits were measured using examiner report on the California Child Q-Sort.

Results.

Results suggest high negative affect was associated with all three ODD symptom domains, while low agreeableness was specifically associated with the angry/irritable ODD symptom domain, and high surgency was associated with the argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptom domains. Negative affect and surgency interacted with agreeableness to predict impairment, but not symptoms: low agreeableness was associated with high impairment, regardless of other trait levels, while high negative affect and high surgency predicted high impairment in the presence of high agreeableness.

Conclusions.

Overall, results suggest ODD is a disorder of high negative affect. Furthermore, low agreeableness is differentially associated with affective ODD symptoms, and high surgency is associated with behavioral ODD symptoms. These traits interact in complex ways to predict impairment. Therefore, negative affect, agreeableness, and surgency may be useful early markers of ODD symptoms and impairment.

Keywords: temperament, externalizing disorders, assessment

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) is a common and impairing behavioral disorder that has a prevalence rate of between 4 and 16% during preschool (Egger & Angold, 2006). ODD is characterized by a pattern of angry, hostile, and/or defiant behaviors and interactions with others and was recently subdivided into three symptom domains: angry/irritable, argumentative/defiant, and vindictive (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), alternatively better supported as two domains of affective versus behavioral symptoms by recent work (e.g., angry/irritable and vindictive symptoms combined in an affective symptom domain; Burke et al., 2014; but see Lavigne et al., 2015 for other supported two-domain solutions). ODD is associated with a number of negative and costly outcomes, such as poor family relations and academic problems (Spira & Fischel, 2005; Posner et al., 2007). Notably, specific ODD symptom domains are believed to differentially predict the high levels of comorbidity often seen in the disorder, with the angry/irritable domain related to internalizing problems, the argumentative/defiant domain related to ADHD, and the vindictive domain related to conduct problems (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). In line with this, ODD is commonly conceptualized as a disorder of negative affect and, secondarily, low effortful control (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009; Stringaris, Maughan, & Goodman, 2010). Yet, empirical tests of trait associations with early ODD remain in short supply, and this was the goal of the present investigation.

Temperament is commonly conceptualized as individual differences in self-regulation and reactivity (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981). Although there are many models of temperament, most recognize at least three temperament traits that are conceptually similar to the model developed by Rothbart (1989): negative affect, surgency, and effortful control (e.g. Eisenberg et al., 1996). Negative affect includes negative emotions such as anger, fearfulness, discomfort, and sadness. Surgency refers to an individual’s positive emotions, activity level, and impulsivity. Effortful control refers to an individual’s inhibitory control, focus of attention, and sensitivity to perception (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981). Importantly, individual differences in temperament traits can be reliably measured via questionnaires as early as infancy (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003).

Similar to temperament, personality refers to an individual’s unique pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (McCrae & Costa, 1987; Tackett, 2006). The most well-established model of personality in adulthood is the Five Factor Model of personality, a model comprised of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Although research on personality traits has historically focused on adults, research suggests that personality traits can also be applied to children (Digman & Inouye, 1986; van Lieshout & Haselager, 1994; Shiner, 1998; Tackett, Krueger, Iacono, & McGue, 2008), even preschoolers (Abe, 2005; De Pauw, Mervielde, & Van Leeuwen, 2009). Further, work suggests that temperament and personality traits may be largely synonymous, with negative affect related to neuroticism, surgency related to extraversion, and effortful control related to conscientiousness (Shiner, 1998; Tackett, 2006). In addition, traits can be well-captured at either a three- (for temperament) or five- (for personality) factor level, depending on the level of analysis; that is, five factor models can be viewed as a lower level of the trait hierarchy compared to three-factor trait models. For example, effortful control is a trait that, at a lower level of analysis, can be further subdivided into effortful control and agreeableness (Nigg, 2006; Shiner & DeYoung, 2011).

Temperament and personality traits exhibit robust associations with psychopathology (Nigg, 2006; Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010); yet, the nature of these associations remains debated. Several models have been put forward which seek to explain how temperament and personality relate to psychopathology; however, the models most supported by research thus far are the vulnerability model and the spectrum model (reviewed by Tackett, 2006; Watson, Gamez, & Simms, 2005). The vulnerability model suggests that temperament and personality traits are risk factors that may contribute to the development of psychopathology. The spectrum model views psychopathology as the extreme end of the normal range of personality traits, whereby extreme personality traits are conceptualized as synonymous with psychopathology. These models are similar in suggesting the possible utility of early assessment of temperament and personality traits since both models suggest that extreme, maladaptive traits may predict psychopathology. Thus, extreme traits may be useful early markers of psychopathology, and tests of the nature of the association between traits and psychopathology are emerging.

As noted above, extant theory (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009) suggests that ODD may be primarily a disorder of negative affect. In line with this idea, prior empirical research indicates that children with disruptive behavior problems exhibit higher negative affect and related traits such as irritability, compared to children without disruptive behavior problems (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998; Dougherty et al., 2011; Eisenberg et al., 200l; Lavigne et al., 2012; 2015; Martel & Nigg, 2006; Lahey, Waldman, & McBurnett, 1999; White, 1999). Further, Stringaris and Goodman’s (2009) theoretical model suggests some specificity of associations between high negative affect and ODD symptom domains such that negative affect may be more strongly associated with the angry/irritable (vs. argumentative/defiant, vindictive) ODD symptom domain, although this idea remains largely untested (but see Ezpeleta et al., 2012). Stringaris and Goodman’s (2009) theoretical model suggests that low effortful control may be more specifically associated with the argumentative/defiant and vindictive (vs. angry/irritable) ODD symptom domains, although little empirical studies have examined this either. Consistent with this idea, work has supported associations between Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBD) and low effortful control, or conscientiousness, and – at a lower level of personality’s hierarchical structure -- low agreeableness (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Gjone & Stevenson, 1997; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2010; Lahey, 2009; Martel, Gremillion, & Roberts, 2012).

Further, child development research suggests complex interactions between traits in prediction of child outcomes. Specifically, negative affect and effortful control—or at lower level of hierarchical analysis, agreeableness—interact to predict child DBDs, such that low effortful control, or low agreeableness, is a particularly salient predictor of child DBDs with high negative affect only related to DBD when effortful control, or agreeableness is high (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Martel, Gremillion, & Roberts, 2012). Recent work suggests similar interactions between positive (vs. negative) affect and effortful control (or agreeableness, at lower levels of conceptualization; Eisenberg et al., in press). This latter finding is in line with theoretical work by Carver and Harmon-Jones (2009) that suggests that anger may be an approach-related emotion, similar to surgency, suggesting possible associations between positive affect and ODD. Although limited work has validated such ideas in relation to ADHD hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms (Martel, 2009; Martel & Nigg, 2006), no known work has examined the relationship between positive affect and ODD. However, such relationships might be expected particularly in relation to ODD symptoms and/or impairment.

To summarize, although ODD is currently conceptualized as a disorder of primarily high negative affect and secondarily low effortful control, empirical tests of this remain in short supply. Further, the possible role of positive affect in anger as an approach-related emotion remains unexamined. Lastly, almost no attention has been given to complex interactions between traits related to affect and control as they may relate to early ODD. This study intends to address these gaps in the existing literature by empirically examining associations between traits related to negative affect, surgency, and effortful control in relation to ODD symptoms during early childhood, a period of time when ODD often first emerges.

The first aim of the study is to evaluate associations of temperament and personality traits with the DSM-5 ODD symptom domains in young children over-recruited for ODD. Based on Stringaris and Goodman’s theoretical model (2009), it is predicted that high negative affect will be more specifically associated with the angry/irritable (vs. argumentative/defiant, vindictive) symptom domain, whereas low effortful control (and low agreeableness) will be more specifically associated with argumentative/defiant and vindictive (vs. angry/irritable) symptom domains. It is also predicted that surgency/positive affect will be associated with one or more ODD symptom domains, based on prior theoretical and empirical work (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Martel 2009; Martel & Nigg, 2006). The second aim of the study is to explore complex, potentially interactive, associations of effortful control (and agreeableness), negative affect, and surgency/positive affect with ODD symptoms and/or impairment. Based on Eisenberg et al. (2009) and Martel, Gremillion, and Roberts’ (2012) work, it is predicted that effortful control (or agreeableness) and negative affect (or positive affect) will interact to predict ODD symptoms and impairment such that low effortful control, or low agreeableness, will be a particularly salient predictor of child ODD symptoms and impairment with high negative or positive affect only related to ODD when effortful control, or agreeableness is high.

Methods

Participants

Overview.

Participants were 109 preschoolers between ages three and six (M=4.77 years, SD=1.11) and their primary caregivers (87% mothers). Fifty-nine percent of the sample was male; 33% of the sample was ethnic minority (mostly African American with some Latino, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Mixed). Parental educational level ranged from unemployed to highly skilled professionals, with incomes ranging from below $20,000 to above $100,000 annually (0=annual income less than $20,000, 1=between $20,000 and $40,000, 2=between $40,000 and $60,000, 3=between $60,000 and $80,000, 4=between $80,000 and $100,000, and 5=over $100,000 annually; see Table 1). Based on multistage and comprehensive diagnostic screening procedures, preschoolers were recruited into two groups: ODD children (n=60) and non-ODD children (n=49). The non-ODD group included preschoolers with subthreshold symptoms to provide a more continuous measure of ODD symptoms. Symptom counts were the focus of analyses, consistent with research suggesting that externalizing behavior may be better captured by continuous dimensions than categorical diagnosis (Krueger, Markon, Patrick, & Iacono, 2005; Markon, Chmielewski, & Miller, 2011) and to be sensitive to the young age of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographics and descriptive information

| Non-ODD | ODD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=49 |

n=60 |

|||

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 4.57 | (1.08) | 4.93 | (1.11) |

| Boys n(%) | 27 | (55.1) | 37 | (61.7) |

| Ethnic minority n(%) | 18 | (36.7) | 18 | (30) |

| African American | 17 | (34.7) | 11 | (18.3) |

| Latino | 1 | (2) | 2 | (3.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.7) |

| Mixed | 0 | (0) | 4 | (6.7) |

| Family income (mode) | 0,1 | 0 | ||

| ODD symptoms*** | 1.78 | (1.14) | 5.32 | (1.26) |

| ODD impairment*** | 6.05 | (4.05) | 10.92 | (3.34) |

| Temperament traits (CBQ) | ||||

| Negative affect*** | 3.91 | (0.97) | 4.56 | (0.94) |

| Effortful control* | 5.04 | (0.77) | 4.68 | (0.96) |

| Surgency* | 4.51 | (0.95) | 4.96 | (0.96) |

| Temperament traits (LabTAB) | ||||

| Perfect circle anger | 5.75 | (6.48) | 4.98 | (5.77) |

| Perfect circle sadness | 1.09 | (1.42) | 2.26 | (3.42) |

| Gift delay effortful control | 9.56 | (2.88) | 9.33 | (2.60) |

| Bubbles positive affect | 21.63 | (8.68) | 18.89 | (8.92) |

| Personality traits (CCQ) | ||||

| Neuroticism | 3.39 | (1.11) | 3.68 | (1.19) |

| Conscientiousness | 6.06 | (1.25) | 5.55 | (1.35) |

| Agreeableness** | 6.27 | (1.15) | 5.46 | (1.31) |

| Extraversion | 6.53 | (1.39) | 6.34 | (1.43) |

Family income modes: 0=annual income < $20,000, 1=between $20,000 and $40,000

Subgroup differences based on independent samples t-tests and chi-squares.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Recruitment and Identification.

Participants were recruited from an urban southeastern community through direct mailings, postings, advertisements, and flyers designed to over-recruit young children with behavior problems. A telephone screening was conducted to rule out children prescribed psychotropic medication (e.g., antidepressants) and children with neurological impairments, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, psychosis, seizure history, head injury with loss of consciousness, or other major medical conditions. All families screened into the study attended a campus laboratory visit and completed written and verbal informed consent procedures consistent with the Institutional Review Board, the National Institute of Mental Health, and APA guidelines. Families were paid $50 for study completion.

Measures

Symptom Counts for ODD and Related Impairment.

Parent report on ODD symptoms and related impairment was available via the clinician-administered Kiddie-Disruptive Behavior Disorder Schedule (K-DBDS; LeBlanc et al., 2008), a semi-structured diagnostic interview for ODD and other DBDs, administered by a trained graduate student clinician. The K-DBDS demonstrates high test-retest reliability and high inter-rater reliability in the preschool population (LeBlanc et al., 2008). DSM-IV ODD symptoms were measured using a dichotomous code (0=absent; 1=present), and totals of 4 or more resulted in diagnosis, consistent with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for ODD (APA, 2013). Separate sum scores for each symptom domain, as specified in the DSM 5 (given that symptoms are the same as DSM-IV), were utilized. ODD-related impairment (e.g., “How much do the behaviors interfere with the child’s ability to play and get along with other kids?”) was measured on a 1 (i.e., not very much) to 3 (i.e., a lot) scale of severity. Sum scores for impairment were utilized. All scales had acceptable internal consistency of .72 or above. Inter-rater reliability in number of symptoms on a random sample of 10% of the sample was .82 or above based on masked ratings. Higher scores indicate more symptoms and impairment.

Temperament Traits.

To measure negative affect, effortful control, and surgency parents completed the very short form of the Child Behavior Questionnaire, a reliable and valid measure for use with this age group (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006). Traits were measured using 12-item scales suggested by Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, and Fisher (2001). Composite scale scores were generated by reverse-scoring selected items and computing the average for negative affect (sample item: gets frustrated when prevented from doing something wanted to do), effortful control (e.g., prepares for trips or outings by planning what needs), and surgency (e.g., likes adventurous activities). The scales had internal consistency in the current sample of .76, .67, and .77 respectively.

Select paradigms from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LabTAB; Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, & Longley, 1999; Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) provided observational ratings of preschool temperament traits. Negative affect (sadness and anger; i.e., “perfect circle”), effortful control (i.e., “gift delay”), and positive affect, or exuberance (i.e. “bubbles”) paradigms were used in the present study (see Goldsmith et al., 1999). All examiners were blind to the child’s diagnosis. In order to assess negative affect (sadness and anger), the child was asked to draw a “perfect” circle; the child was corrected and asked to redraw their circle for two minutes. During this time, verbal, facial, and behavioral expressions of sadness and anger, as well as intensity of and latency to sadness and anger were coded as present or absent in five-second increments. Two composite scores were generated by summing all coded behaviors for sadness and for anger across the two minutes. In order to assess effortful control, children were asked to wait with their back turned while the examiner wrapped a gift; the child was instructed not to touch the gift while the examiner left to room to retrieve a bow for the gift. Extent of peeking for the entire segment was coded on a five-point scale (1 = child peeks the entire time; 5 = child never peeks). To assess positive affect, children played with a bubble gun for one minute. Presence or absence of positive motor activity (e.g., clapping) and verbal expressions of positive affect (e.g., laughter) were tallied within ten-second increments. To generate composite scores for positive motor activity and verbal expressions of positive affect, a sum of all tally marks across the one minute was computed. Inter-rater reliability was acceptable for each individual coded category within construct (kappas > .78). Higher scores denote higher levels of traits.

Personality Traits.

To examine personality traits, specifically neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion, an examiner who was not privy to diagnosis and interacted with the child for at least three hours under structured conditions (i.e., during LabTAB and questionnaire administration) completed the California Child Q-Sort (CCQ; Block, 2008; Block & Block, 1980), a developmentally sensitive measure (John et al., 1994; Martel & Nigg, 2006). The CCQ is a typical Q-Sort consisting of 100 cards, which must be placed in a forced-choice, nine-category, rectangular distribution. Scales developed by John, Caspi, Robins, Moffitt, and Stouthamer-Loeber (1994) for neuroticism (sample item: fearful or anxious), conscientiousness (e.g., resourceful in initiating activities), agreeableness (e.g., considerate and thoughtful of other children), and extraversion (e.g., vital, energetic, lively) were used. Composite scale scores were generated by reverse-scoring selected items and computing the average. Internal consistency for these trait scales was .74, .65, .86, and .81, respectively.

Data Analysis

First, temperament and personality traits and ODD symptoms were examined by 2 independent raters for item overlap. No items appeared to be overlapping when using a close conceptual overlap criterion (i.e. items had to designate closely related ideas), and agreement between raters was 100%; thus, all items were included in analyses. Next, demographic and diagnostic group differences were examined using t-tests, chi-square statistics, and analysis of variance. Then, a correlation matrix of all main study variables was conducted.

To evaluate main study aims and hypotheses regarding simple associations between traits and ODD symptoms to reduce utilized trait variables, bivariate correlations were conducted followed by path analysis which allowed for simultaneous estimation of all paths between traits and ODD symptom domains in order to control for shared covariance among symptom domains and traits. To evaluate main study aims and hypotheses regarding complex, interactive associations between traits and ODD-related impairment, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with main effects entered as step 1 and interactions between continuous variables entered at step 2. In the case of significant interactions, we dichotomized variables at one standardized deviation below and above to mean in order to graphically depict moderation effects.

Based on a sample size of 109 and an expected medium effect size (r=.3; Martel et al., 2012), power was adequate (.90 for correlations and path analysis and .75 for hierarchical regressions).

Results

Demographics and Diagnostic Group Differences

As noted in Table 1, based on t-tests and chi-square statistics, there were no demographic differences across diagnostic group (ODD vs. non-ODD; all p>.30), and no significant correlations between demographics and ODD symptoms (r range −.090-.177, all p>.08) with the exception that univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant mean differences in ODD symptoms based on family income (F[1,98]=2.496, p=.04) with lower income levels related to higher ODD symptoms. Mean levels of ODD symptoms and associated impairment, as well as levels of negative affect, surgency, effortful control, and agreeableness were significantly different between the ODD and non-ODD diagnostic groups in the expected direction (all p<.04 to p<.001). All other trait measures exhibited no significant differences between diagnostic groups (all p>.07). No demographic variables, with the exception of family income (F[1,98] range 2.297–2.854, p<.04), exhibited significant associations with the ODD symptom domains; thus, the effect of family income on study results was examined in secondary analyses.

Associations between Traits and ODD Symptom Domains

Bivariate correlations between traits and ODD symptom domains were conducted in order to determine which traits to focus on in subsequent analyses, shown in Table 2. High negative affect was significantly correlated with all symptom domains (angry/irritable r=.328, argumentative/defiant r=.341, vindictive r=.309, all p<.001), but neither neuroticism, nor perfect circle anger, nor perfect circle sadness were significantly associated with any of the symptom domains (r range −.086-.168, all p>.1). Neither effortful control nor gift delay effortful control exhibited significant associations with any of the symptom domains (r range −.144-.048, all p>.15), but low conscientiousness was significantly correlated with the angry/irritable symptom domain (r=−.288, p=.004), but not with the argumentative/defiant or vindictive symptom domains (r range −.077- −.015; all p>.46). Low agreeableness was significantly associated with the angry/irritable and argumentative/defiant symptom domains (r=−.504, p<.001; r=−.242 p<.02), but not with the vindictive symptom domain (r=−.120, p=.24). Extraversion was not significantly correlated with any of the symptom domains (r range −.026-.059; all p>.57). High positive affect was significantly correlated with the argumentative/defiant symptom domain (r=.279, p=.02), but not with the angry/irritable or vindictive symptom domains (r range −.138- −.065, all p>.2), while high surgency was significantly associated with all the symptom domains (r range .204-.217; all p<.04). Overall, high negative affect, low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, and high surgency exhibited the strongest associations within each trait with one or more ODD symptom domains. Based on these results, they were chosen as the focus of subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Correlations between temperament traits and personality traits and ODD symptom domains

| Angry/Irritable | Argumentative/Defiant | Vindictive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBQ Negative affect | .382*** | .341*** | .309*** |

| CCQ Neuroticism | .168 | −.028 | −.011 |

| LabTAB Perfect circle anger | −.078 | −.070 | −.086 |

| LabTAB Perfect circle sadness | .138 | −.059 | −.088 |

| CBQ Effortful control | −.102 | −.141 | −.091 |

| CCQ Conscientiousness | −.288** | −.077 | −.015 |

| CCQ Agreeableness | −.504*** | −.242* | −.120 |

| LabTAB Gift delay effortful control | −.110 | −.144 | .048 |

| CBQ Surgency | .204* | .217* | .206* |

| CCQ Extraversion | .059 | −.019 | −.026 |

| LabTAB Bubbles positive affect | −.065 | .279* | −.138 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Specificity of Associations between Traits and Symptom Domains

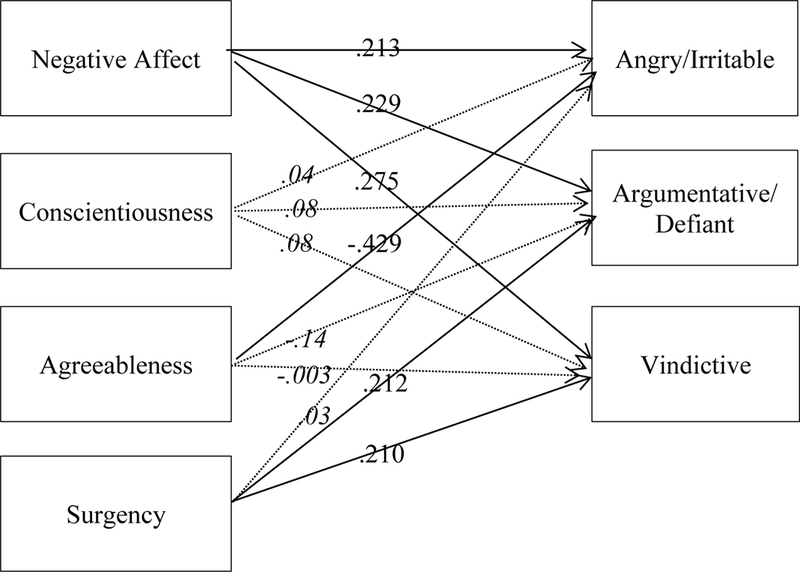

Path analysis was conducted in Mplus in order to examine specificity of associations between traits and ODD symptom domains. All three symptom domains were regressed simultaneously on negative affect, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and surgency (AIC=594.03, BIC=652.94), and significant difference tests were conducted to examine relative differences in associations between traits and ODD symptom domais. Results, shown in Figure 1, indicated that high negative affect was significantly associated with the angry/irritable, argumentative/defiant, and vindictive ODD symptom domains (β=.213, p=.03; β=.229, p=.01; β=.275, p<.001). Low agreeableness was significantly associated with the angry/irritable ODD symptom domain (β=−.429, p<.001), and this association was specific in the sense that it was significantly different than the association between agreeableness and other ODD symptom domains (t>2.04, p<.04). High surgency was significantly associated with the argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptom domains (β=.212, p=.03; β=.210, p=.03), but this association was not specific as it was not significantly different than the association between surgency and the angry/irritable symptom domain (t<1.24, p>.22). Conscientiousness was not significantly associated with any of the ODD symptom domains (β range .036-.093, all p>.5). Overall, this suggests a more general association between high negative affect and all three ODD symptom domains. However, low agreeableness appears to be more specifically associated with the angry/irritable ODD symptom domain.

Figure 1.

Traits as Predictors of ODD Symptom Domains

Note. Dotted paths and italicized coefficients were nonsignificant.

Traits as Predictors of ODD Symptoms and Impairment

In order to preliminarily examine associations between traits and ODD impairment, bivariate correlations were conducted between traits and ODD-related impairment. High negative affect (r=.545, p<.001), low conscientiousness (r=−.313, p=.004), low agreeableness (r=−.507, p<.001), and high surgency (r=.388, p<.001) were significantly associated with increased ODD-related impairment.

Next, hierarchical regression was utilized to examine whether traits interacted in predicting ODD-related impairment or ODD symptoms with main effects entered as step 1 and interactions (i.e., agreeableness x negative affect and agreeableness x surgency) entered at step 2. Neither negative affect nor surgency significantly interacted with conscientiousness to predict ODD-related impairment (ΔR2=.001, β=.028, SE=.33; p=.78 for negative affect; (ΔR2=.001, β=.024, SE=.46 p=.82 for surgency) or ODD symptoms (ΔR2=.001, β=.005, SE=.16 p=.96 for negative affect; ΔR2=.001, β=.023, SE=.21 p=.91 for surgency). Negative affect and surgency significantly interacted with agreeableness to predict ODD-related impairment (ΔR2=.052, β=.233, SE=.25, p<.05 for negative affect; ΔR2=.063, β=.253, SE=.27, p<.05 for surgency), but not ODD symptoms (ΔR2=.002, β=.12, SE=.13 p=.18 for negative affect; ΔR2=.03, β=.18, SE=.14 p=.06 for surgency). As depicted in Figures 2 and 3 respectively, low agreeableness was related to increased ODD-related impairment, regardless of the level of negative affect or surgency. However, when agreeableness was high, high negative affect was significantly related to increased ODD-related impairment (t=4.47, p<.01), but the association between negative affect and impairment was not significantly different from zero when agreeableness was low (t=−.36, p=.72). A similar pattern was observed for surgency such that, when agreeableness was high, high surgency was significantly related to increased ODD-related impairment (t=3.35, p<.01), but the association between surgency and impairment was not significantly different from zero when agreeableness was low (t=−1.45, p=.15). Therefore, negative affect and surgency interact with agreeableness in their prediction of ODD-related impairment, but not symptoms.

Figure 2.

Interaction between negative affect and agreeableness predicting ODD-related impairment

Note. A=Agreeableness.

Figure 3.

Interaction between surgency and agreeableness predicting ODD-related impairment

Note. A=Agreeableness.

Secondary Checks

Income as a Covariate.

Since there were significant mean differences in ODD symptoms based on family income, all analyses were conducted a second time covarying income. All significant findings mentioned above survived correction for family income, with two exceptions. When family income was entered into the path analysis examining the specificity of associations between traits and ODD symptom domains, the associations between high surgency and the argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptom domains dropped to non-significance (β=.195, p=.07; β=.175, p=.11).

Comparison of DSM-5 3-Domain Model and Recent 2-Domain Models.

We conducted secondary analyses comparing the DSM-5 3-domain ODD model with 2 recent 2-domain ODD models: (1) an affective (i.e., being touchy, angry, and loses temper) and behavioral (i.e., argues, defies, annoys others, blames others, spiteful/vindictive) model (Burke et al., 2014) and (2) a negative affect (i.e., touchy, angry, spiteful/vindictive) and behavioral (i.e., argues, defies, and loses temper) model (Lavigne et al., 2015). We reran the correlation matrix between all traits and these 2-factor ODD models with very few substantial differences between the DSM-5 angry/irritable and affective (Burke et al., 2014; or negative affect; Lavigne et al., 2015) domains or between the DSM-5 argumentative/defiant and behavioral (Burke et al., 2014; Lavigne et al., 2015) domains in the sense that the patterns of significant and nonsignificant findings were almost identical (results available upon request). We also conducted partial correlations among symptom domains and agreeableness, controlling for the alternative symptom domain in order to examine whether the specific association between agreeableness and the DSM-5 angry/irritable domain also held for the affective (or negative affect) domain. Significant, specific associations between low agreeableness and the affective domain held for the Burke et al. (2014) affective domain (p=.002), but not for the Lavigne et al. (2015) negative affect domain (p=.62), based on significant difference tests.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between traits related to negative affect, effortful control, and surgency and ODD symptoms in young children. Results suggested significant associations between high negative affect and all three ODD symptom domains. However, low agreeableness was specifically associated with the angry/irritable ODD symptom domain, while high surgency was only somewhat specifically associated with the argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptom domains. Both negative affect and surgency interacted with agreeableness to predict more ODD-related impairment, but not symptoms, such that when agreeableness was low, impairment was high regardless of the level of negative affect or surgency and, when agreeableness was high, high negative affect and high surgency (but not low negative affect or low surgency) were associated with higher impairment. Overall, these results suggest that high negative affect, low agreeableness, and high surgency are strongly associated with ODD symptoms and related impairment during preschool, with somewhat differential associations with ODD symptom domains, and affect and agreeableness exhibiting interactive effects in relation to impairment.

Consistent with Stringaris and Goodman’s (2009) conceptualization of ODD as a disorder of negative affect, high negative affect was associated with all three ODD symptom domains, not just the angry/irritable ODD symptom domain. Thus, ODD may primarily be a disorder of high negative affect. This is in line with work suggesting that children with ODD are at increased risk for comorbidity such as depression and anxiety later in life (Lavigne et al., 2001; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). Yet, results of this study do not support associations between low effortful control and ODD symptoms, despite diagnostic group differences, and this is somewhat counter to prior work in this area (e.g., Dougherty et al., 2011; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Lavigne et al., 2012). This may be due to the young age of our sample, the primacy of more affectively-driven traits in this age range, or impaired parental reporting abilities in the severely stressed urban sample studied. Yet, it is also possible that there are diagnostic differences are not explained by symptoms or symptom domains, or there was low power to detect symptom domain level effects. However, low agreeableness, related to conscientiousness and effortful control, but measured at a lower hierarchical level of trait structure, exhibited prominent associations with ODD in this age range, particularly with the angry/irritable domain. This is in line with recent work by Burke and colleagues (2014) suggesting an irritability dimension within ODD and might be viewed as consistent with recent calls to subdivide ODD into two (vs. 3) symptom domains using an affective versus behavioral distinction (Herzhoff & Tackett, 2016; Lavigne et al., 2015) since our affective domain, characterized by angry/irritable symptoms, was specifically underpinned by low agreeableness, and this finding also found in relation in Burke et al. (2014)’s 2-domain model (although it should be noted that such specificity was not found in relation to Lavigne et al.’s [2015] model).

Importantly, this study was the first to demonstrate that high surgency was associated with ODD, perhaps particularly with the argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptom domains, although this difference in associations was not significant. In line with hypotheses, this finding suggests that high positive affect and high negative affect, may be risky, in line with the spectrum conceptualization of trait-psychopathology associations. Associations between high positive affect and ODD are in line with Carver and Harmon-Jones’ (2009) theory of anger as an approach-related emotion, as well as neurobiological findings suggesting decreased reward sensitivity in these children which may lead to higher levels of surgency-related behaviors in order to stimulate positive affect (Matthys, Vanderschuren, & Schutter, 2013). These results are also consistent with prior work finding associations between high positive affect and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD symptoms (Martel, 2009; Martel & Nigg, 2006). We would take such prior work a step further by suggesting that different disorders are described not just by the expression of a single extreme trait, but rather by different combinations of extreme traits interacting with one another. In this way, high positive affect may be part of what distinguishes externalizing from internalizing disorders (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010).

This study’s findings suggest that negative affect and surgency interact with agreeableness in relation to ODD-related impairment, consistent with work by Eisenberg et al. (2009) and particularly Martel, Gremillion, and Roberts (2012), which suggested low effortful control is a primary route to ADHD, and negative affect is a secondary pathway. In regard to ODD, current findings suggest that low agreeableness is a primary pathway to increased ODD-related impairment and high negative affect and high surgency are secondary pathways. These findings highlight the importance of agreeableness for the development of prosocial behavior and effective management of interpersonal conflict (Eisenberg et al., 1999; Jensen-Campbell, Gleason, Adams, & Malcolm, 2003), often lacking in ODD. In addition, this work suggests that high surgency can be a risk factor for psychopathology in the right circumstances and when manifest with particular combinations of other traits.

The study had a number of strengths, including a well-characterized sample of children over-recruited for ODD and multiple measures of traits and clinical symptoms, but it also had limitations. There is the possibility of results being due to a type I error, given that multiple analyses were conducted. There may be shared source variance between temperament traits and ODD symptoms, given that the same informant completed both measures in some cases. While overlapping items between traits and ODD symptoms were screened, conceptual overlap between psychopathology and traits may still be an issue. In addition, we did not obtain interrater reliability on the CCQ, and this measure is not independent of other study measures; these are study limitations. Importantly, since this sample was a community-recruited sample, over-recruited for ODD symptoms in an urban setting, the results may not generalize to other populations; these results should be replicated using other samples. Further, this study is cross-sectional in nature, and longitudinal extension of the current work will be important. While the current study shows that there are distinct associations between temperament and personality traits and ODD symptoms and impairment, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the longitudinal relationship between these traits and the disorder.

Study results may have clinical utility. For example, study results suggest that it may be useful for clinicians to conduct early assessment of maladaptive variants of negative affect, agreeableness, and surgency in young children at risk for ODD. Since these traits can be reliably identified earlier than ODD itself (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003), identification of children with extreme traits may be able to lead to earlier identification of children at risk for a disorder with severe public health outcomes, including poor family relations, academic problems, and high comorbidity with other disruptive behavior problems (Spira & Fischel, 2005; Posner et al., 2007). Further, study results suggest that high negative affect, high surgency, and low agreeableness may be useful for understanding the level of impairment the child is likely to experience, which has real-world implications for the quality of the child’s social relationships (Eisenberg et al., 1999; Jensen-Campbell, Gleason, Adams, & Malcolm, 2003). In sum, early assessment of these traits could be helpful for determining which children are most in need of early intervention for ODD.

Overall, this study addressed the relationship between temperament traits, personality traits, and ODD symptoms in young children. Study results partially support Stringaris and Goodman’s (2009) theory of ODD, suggesting that it is a disorder of high negative affect. Results also advance work in this area by highlighting the important roles of low agreeableness and high surgency. While high negative affect appears to be more generally associated with ODD symptoms, low agreeableness appears particularly associated with angry/irritable ODD symptoms, and high surgency might be somewhat more related to argumentative/defiant and vindictive ODD symptoms. Further, negative affect and surgency appear to interact with agreeableness to predict ODD-related impairment. Collectively, this suggests the importance of the early assessment of these traits in young children in order help identify children at high risk for ODD symptoms and impairment and to guide targeted early intervention.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 5R03 HD062599–02 to M. Martel. We are indebted to the families who made this study possible.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 5R03 HD062599–02 to M. Martel.

Footnotes

Ethical Standards

All families screened into the study completed written and verbal informed consent procedures consistent with the Institutional Review Board, the National Institute of Mental Health, and APA guidelines.

There is no financial or other conflict of interest to report.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abe JAA (2005). The predictive validity of the Five-Factor Model of personality with preschool age children: A nine year follow-up study. Journal of Research in Personality, 39(4), 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Block B (2008). California Q-sort psychometrics. The Q-sort character appraisal: Encoding subjective impression of persons quantitatively (55–62). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Block J, & Block JH (1980). The California Child Q-set. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, & Waldman ID (2014). Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(4), 841–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & Harmon-Jones E (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 183–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1998). Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 469–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SS, Mervielde I, & Van Leeuwen KG (2009). How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(3), 309–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM, & Inouye J (1986). Further specification of the five robust factors of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, Dyson M, Olino TM, Durbin CE, & Klein DN (2011). Preschoolers’ observed temperament and psychiatric disorders assessed with a parent diagnostic interview. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2), 295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Murphy BC, Losoya SH, & Guthrie I (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R (1996). The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 141–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Shepard SA, Cumberland A, & Carlo G (1999). Consistency and development of prosocial dispositions: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 70(6), 1360–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M (2009). Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 988–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, & Angold A (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3‐4), 313–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Penelo E, & Domènech JM (2012). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3‐year‐old preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(11), 1128–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, & Rothbart MK (2003). Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development, 26(1), 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gjone H, & Stevenson J (1997). A longitudinal twin study of temperament and behavior problems: Common genetic or environmental influences? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1448–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, & Prescott A (1999). The laboratory temperament assessment battery: Preschool version. Madison: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Herzhoff K, & Tackett JL (2016). Subfactors of oppositional defiant disorder: converging evidence from structural and latent class analyses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(1), 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Micco JA, van Grondelle A,... & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Clinical outcomes of laboratory-observed preschool behavioral disinhibition at five-year follow-up. Biological psychiatry, 62(6), 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Gleason KA, Adams R, & Malcolm KT (2003). Interpersonal conflict, agreeableness, and personality development. Journal of Personality, 71(6), 1059–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Caspi A, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, & Stouthamer-Loeber M (1994). The “little five”: Exploring the nomological network of the five-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Development, 65, 160–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HW, Cho SC, Kim BN, Kim JW, Shin MS, & Yeo JY (2010). Does oppositional defiant disorder have temperament and psychopathological profiles independent of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder?. Comprehensive psychiatry, 51(4), 412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, & Harlan ET (2000). Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, & Watson D (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, & Iacono WG (2005). Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 537–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64(4), 241–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID, & McBurnett K (1999). Annotation: the development of antisocial behavior: an integrative causal model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(5), 669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Bryant FB, Hopkins J, & Gouze KR (2015). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in young children: model comparisons, gender, and longitudinal invariance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 423–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Cicchetti C, Gibbons RD, Binns HJ, Larsen L, & DeVito C (2001). Oppositional defiant disorder with onset in preschool years: Longitudinal stability and pathways to other disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(12), 1393–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Dahl KP, Gouze KR, LeBailly SA, & Hopkins J (2015). Multi-domain predictors of oppositional defiant disorder symptoms in preschool children: cross-informant differences. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(2), 308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Gouze KR, Hopkins J, Bryant FB, & LeBailly SA (2012). A multi-domain model of risk factors for ODD symptoms in a community sample of 4-year-olds. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 741–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc N, Boivin M, Dionne G, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, & Tremblay RE (2008). The development of hyperactive-impulsive behaviors during the preschool years: The predictive validity of parental assessments. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 977–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Chmielewski M, & Miller CJ (2011). The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: A quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(5), 856–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM (2009). A new perspective on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Emotion dysregulation and trait models. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 50(9), 1042–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Gremillion ML, & Roberts B (2012). Temperament and common disruptive behavior problems in preschool. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 874–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, & Nigg JT (2006). Child ADHD and personality/temperament traits of reactive and effortful control, resiliency, and emotionality. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(11), 1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, Vanderschuren LJMJ, & Schutter DJLG (2013). The neurobiology of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: altered functioning in three mental domains. Development and psychopathology, 25(1), 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Costa PT (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT (2006). Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 395–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Melvin GA, Murray DW, Gugga SS, Fisher P, Skrobala A (2007). Clinical presentation of the Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in preschool children: The Preschoolers with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Study (PATS). Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17(5), 547–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, & Rothbart MK (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87(1), 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK (1989). Temperament in childhood: A framework In Kohnstamm GA, Bates JE, & Rothbart MK (Eds.), Temperament in childhood, (59–73). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, & Fisher P (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72(5), 1394–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Derryberry D (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament In Lamb ME & Brown AL (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 37–86). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL (1998). How shall we speak of children’s personalities in middle childhood? A preliminary taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 308–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, & DeYoung CG (2011). The structure of temperament and personality traits: A developmental perspective In Zelazo PD (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 113–141). New York, NY: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Spira EG, & Fischel JE (2005). The impact of preschool inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity on social and academic development: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(7), 755–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, & Goodman R (2009). Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(3), 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Maughan B, & Goodman R (2010). What’s in a disruptive disorder? Temperamental antecedents of oppositional defiant disorder: Findings from the Avon longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(5), 474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL (2006). Evaluating models of the personality-psychopathology relationship in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 584–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, & McGue M (2008). Personality in middle childhood: A hierarchical structure and longitudinal connections with personality in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1456–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lieshout CFM, & Haselager GJT (1994). The Big Five personality factors in Q-sort descriptions of children and adolescents In Halverson CF, Kohnstamm GA, & Martin RP (Eds.), The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood (293–318). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Gamez W, & Simms LJ (2005). Basic dimensions of temperament and their relation to anxiety and depression: a symptom-based perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 3(1), 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- White JD (1999). Review personality, temperament, and ADHD: a review of the literature. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(4), 589–598. [Google Scholar]