Abstract

Approximately one third of early childhood pupils in Ghana are struggling with meeting basic behavioral and developmental milestones, but little is known about mechanisms or factors that contribute to poor early childhood development. With a lack of developmental research to guide intervention or education program and policy planning, this study aimed to address these research gaps by examining a developmental mechanism for early childhood development. We tested a mediational mechanism model that examined the influence of parental wellbeing on parenting and children’s development. Two hundred and sixty-two Ghanaian parents whose children attended early childhood classes (nursery to 3rd grade) were recruited. Data were gathered through parent interviews and Structural Equation Modeling was utilized to examine pathways of the model. Results support the mediational model that Ghanaian parents’ depression was associated with less optimal parenting, and in turn greater child externalizing behavioral problems. This study adds new evidence of cross cultural consistency in early childhood development.

Keywords: Wellbeing, Parental Depression, Social Support, Parenting, Early Childhood, Child Development, Social Emotion Development, Ghana

INTRODUCTION

Early experiences are formative for future development and health, as early experiences shape the architecture of the developing brain and healthy behaviors in ways that have lasting consequences into childhood and adulthood [1]. Young children require substantial support from their caregivers to develop a broad array of behaviors and social skills, which form the foundation for all other aspects of children’s functioning, from forming good health habits, meaningful relationships and friendships, and successfully adapting to school, family and community life. Despite the importance of promoting early childhood development, such research is limited in many low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). In Ghana, where this study took place, national efforts have been made over the past few years to expand a two-year free and compulsory pre-primary education, which has led to Ghana having one of the highest preschool enrollment rates (68%) among LMICs [2]. However, approximately 33% of early childhood pupils continue to struggle with meeting basic behavioral and developmental milestones, including following directions, working independently, avoiding distraction, getting along with others, and avoiding aggression [3]; and 4% to 27% of school-aged children had mental health problems (i.e., 18% with abnormal problem, 27% with emotion problem, 23% with conduct problem, 4% with hyperactivity using Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) [4]. However, little research has been conducted to understand mechanisms for poor early childhood development. Therefore, domains of familial contextual factors (e.g., parental wellbeing, socioeconomic characteristics, support resources) and parenting (e.g., beliefs, involvement in education, social emotional support, behavioral management) that are critical to early development remain unknown. This study aimed to address this literature gap by examining the role of parental wellbeing in parenting, and in turn in child development to better understand the mechanisms for promoting healthy development in young Ghanaian children.

Parenting Research in Ghana

Parenting research in Ghana is limited and has not focused on early childhood. Prior to 1990, most research was conducted from anthropological perspectives and largely focused on social parenthood, child fosterage, and parenthood in patriarchal societies, which are deeply embedded in Ghanaian family system and cultural contexts [5–7]. Similar to other African cultures and family systems, many Ghanaian adults value a patriarchal system whereas the father or eldest male in the household usually hold the power for decision-making, including decisions regarding child rearing. Biological parents in Ghanaian families play major roles in child upbringing, but other adults can also play important roles in parenting (social parenthood). Social parenthood endorses that every adult of reasonable age in households or communities can make an input in how the child of another is raised and this may include disciplining the child if he/she is caught misbehaving [8]. This arrangement of family life has changed over time because of globalization, migration and urbanization [9]. There is also a growing number of single families and women headed households, and weakening of authority/power of fathers and male traditional leaders in families [8]. However, whether parenting and child developmental theories derived from Western cultures can be applied to modern Ghanaian parenthood contexts remain to be tested.

Recent parenting research in Ghana has focused more on characterizing Ghanaian families’ parenting practice patterns and examining Western parenting constructs and their associations with child outcomes in Ghana. Studies have found that parenting in Ghana largely fit into the authoritarian parenting style, characterized by high degree of control and low levels of warmth [8]. However, there is also a shift in parenting style over time and across generations. Younger generations of parents who are also resident in urban areas are more likely to practice an authoritative parenting style, where there is a fair balance between warmth, parental control and disciplinary strategies [10, 11]. In addition, studies also reported a low to medium level of learning support/engagement at home provided by Ghanaian parents. For example, only 33 percent of Ghanaian parents read to their young child in the previous three days (compared to 54% in all LMICs and 83% in the United States), which placed Ghanaian parents’ engagement ranking in the 12th place relative to the 28 LMICs included in the study [3, 12]. Low parental engagement might explain why one-third of young Ghanaian children struggle with meeting basic developmental milestones (as described above) [3].

In parenting and child development research, a few studies have been conducted. Most have focused on Baumrind’s parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, permissive; [13] and have examined the relationships between parental warmth/acceptance/ nurturance, autonomy support, restriction/control, structure, and wellbeing on child development [14–16]. Overall, these studies have supported generalizability of Western constructs/theories to Ghanaian contexts. For example, studies have found higher parental structuring of child activities in Ghanaian families was related to higher children’s cognitive competence, higher parental autonomy support was related to fewer child depressive symptoms and higher motivation and engagement in school, and higher parental control and more use of authoritarian parenting style were associated with poorer child regulation around school work and lower academic engagement [15]. In addition, parental wellbeing (e.g., depression, anxiety, HIV/AIDS) was associated with lower parenting stress [16] and fewer problem behaviors in children [4]. Unfortunately, most parenting studies were focused on school-aged children and adolescents. We have not identified published studies focused on early childhood parenting and child development.

The Present Study

Building on the existing literature, the current study investigates the links between parental wellbeing, parenting, and early childhood pupils’ outcomes in Ghanaian families. This study was guided by the Family Stress Model [17–20], which posits that level of parental and environmental-related stress influences quality of parenting, which impacts child outcomes. We examined three domains of parental wellbeing (depression, health, and perceived social support), seven domains of parenting (including positive and negative domains of parenting that are commonly studied in parenting research), and five domains of child development (including social competence, common domains of behavioral problems, and overall health).

METHODS

Participants

Study participants included 262 Ghanaian parents whose children attended early childhood classes (pre-primary to 3rd grade). Children were not the subject of this study. Parents in this study were defined as biological birth parents or non-birth adult primary caregivers who lived with target children and played a major caregiver role. Non-birth adult primary caregivers were chosen because of the widely accepted practice of social parenthood that sometimes arises from the biological parents not being actively involved in the children’s lives (due to parental health or different living arrangements).

The mean age of parents was 38.23 years (SD = 8.12 years, range 18 to 69 years) and the majority were female (64%). About one fifth of parents (22%) were single, 88% were employed, 64% identified as the child’s mother (25% fathers, 3% grandparents, and 8% relatives), and 34% had educational attainment of primary school or less and 66% secondary or higher. Most families (87%) were Christian (10% Muslim, and 3% Catholic) and, on average, had 2.92 children (SD = 1.50) and 5.43 (SD = 2.06) household members. Children were on average 6.83 years old (SD = 1.56 years, range 3 to 10 years), 51% were boys, and all were enrolled in Nursery to Primary 3 in Accra, the capital city of Ghana.

Procedure

Participants were recruited between March and August 2016 from 10 schools in diverse communities of Accra. Parents of children enrolled in Nursery to Primary 3 were eligible for the study and primary schools were identified through a regional school list. About 25 families from each school were randomly selected and recruited through introduction of school staff. Eligible primary caregivers who agreed to participate were provided with oral or written informed consent. For parents who were literate, a written consent was given, and a signed consent form was documented. For parents who were illiterate, an oral consent was given, and a literate witness (e.g., research staff, community guide) signed the consent form on behalf of the participant, which was then documented. After consent, parents were scheduled for an interview in their children’s school by a trained bachelor or master-level social science researcher. Consents and interviews were conducted in English (52%; the official language in Ghana schools), Akan (42%; the primary local language), or Ga (6%) based on parents’ preference. The Akan and Ga versions of measures were translated and back-translated, and a team review approach was used to resolve any discrepancies between the versions [21]. Children did not participate in the evaluation. The study procedures and method of consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Humanities, University of Ghana (IRB number: ECH 007/15-16) and NYU School of Medicine (IRB number: i15-00812).

Measures

Measures included in this study have demonstrated to be reliable and valid with Ghanaian population. Scale reliability (assessed using internal consistency Cronbach’s Alpha/α based on our current study sample) and validity (associations of study constructs; see Table 1) for all study measures are reported below.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Alphas, and Correlations Among Study Variables

| M (SD) | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Well-Being | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Depression | 3.13 (4.15) | .85 | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. Social Support | 3.88 (.92) | .96 | −.22ǂ | – | ||||||||||||

| 3. Health | 2.23 (.78) | .89 | .33ǂ | −.09 | – | |||||||||||

| Parenting | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Belief of using Corporal Punishment | 2.70 (1.26) | .93 | .11 | −.19** | .12 | – | ||||||||||

| 5. Discourage Negative Emotion | 1.56 (.65) | .84 | .45ǂ | −.09 | .21** | .19** | – | |||||||||

| 6. Parent-Child Conflict | 2.00 (.76) | .90 | .17** | −.22ǂ | .13* | .32ǂ | .19ǂ | – | ||||||||

| 7. Severe Physical Abuse | .12 (.32) | .71 | .23ǂ | −.04 | .01 | .06 | .25ǂ | .07 | – | |||||||

| 8. Mild Physical Abuse | 1.02 (.71) | .67 | .27ǂ | −.18** | .16** | .35ǂ | .35ǂ | .43ǂ | .38ǂ | – | ||||||

| 9. Psychological Abuse | .60 (.56) | .63 | .32ǂ | −.15** | .12 | .32ǂ | .34ǂ | .37ǂ | .41ǂ | .56ǂ | – | |||||

| 10. Involvement in Education | 3.74 (1.91) | .67 | −.18** | .20** | −.14* | −.26ǂ | −.23ǂ | −.13* | .04 | −.14* | −.18** | – | ||||

| Child Health | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Social Competence | 3.37 (.71) | .88 | −.07 | .18** | −.18** | −.32ǂ | −.12 | −.41ǂ | .01 | −22ǂ | −.25ǂ | .19** | – | |||

| 12. Externalizing Problem | 3.85 (2.64) | .69 | .04 | −.06 | .10 | .37ǂ | .23ǂ | .49ǂ | .08 | .36ǂ | .29** | −.10 | −.40ǂ | – | ||

| 13. Attention Problem | 3.76 (2.37) | .71 | .10 | −.04 | .03 | .32ǂ | .10 | .44ǂ | .05 | .37ǂ | .31ǂ | −.03 | −.29ǂ | .45ǂ | – | |

| 14. Internalizing Problem | 1.03 (1.47) | .73 | .12* | −.15* | .14* | .09 | .09 | .33ǂ | .01 | .13* | .17** | −.12* | −.10 | .21** | .09 | – |

| 15. Child Overall Health | 6.05(1.14) | .68 | −.20** | .21** | −.19** | −.06 | −.18** | −.21** | −.08 | −.12* | −.14* | .22ǂ | .14* | −.03 | −.07 | −.11 |

Note. α is reliability (internal consistency) for each study scale using our Ghanaian sample.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001. For parental depression (PHQ9), estimate 8% of parents had moderate to severe depression (using cut-off 10).

Parental Wellbeing

Three self-report measures were used to assess parental wellbeing. Parental Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; 10 items; α =.85), a brief depression screening measure that has been widely used and validated in many countries [22–24]. Parents rated 9 symptom items on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all; 3 = nearly every day). The scale also includes an overall functioning rating that evaluates the level of functional impairment (0 = not at all difficult to function, 3 = extremely difficult to function). A total score was created for 9 symptom items, which was used for analyses. Social Support (4 items; α =.96) was evaluated using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [25]. The scale evaluates perceived support for comfort, sharing emotion, and needing help on a 5-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Parental health was assessed based on parent perception of overall health, physical health, and quality of life (3 items; α =.89 for the study sample) on a 5-point scale (1=poor, 5= excellent).

Parenting

Five parent self-report measures were used to assess seven areas of parenting. Constructs that had been identified as significant predictors for child development in the Western and cross cultural literature (including research based on Africa, Asian and diverse ethnic populations) were targeted [26–30].

The Responses to Children and Emotion Questionnaire (RTCE; [31] was used to assess parent emotion socialization practices. Parents were asked to rate how often they used different socialization strategies (i.e., punish, neglect) in response to child negative emotions (i.e., sad/feeling down, angry/feeling frustrated) on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all like me; 5 = a lot like me). For this study, the summary scores of Discouragement of Emotional Socialization (10 items, combine punish and neglect of sadness and anger, α = .84) was used. The Parent-Child Relationship Scale [32] measures Conflicted Parent-Child Relationship (12 items; α =.90; e.g., child and I always seem to be struggling with each other) on a 5-point scale (1 = definitely does not apply; 5 = definitely applies). Attitude About Corporal Punishment scale (3 items; α = .93) assesses parents’ attitude toward corporal punishment (e.g., in order to bring up a child properly, you need to physically punish your child) on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) [26] .

The ISPACN Child Abuse Screening Tool- Parent Version (ICAST-P) was used to assess parents’ use of discipline practices, especially harmful forms of child discipline [33]. It has been applied in six countries and translated into seven languages, and has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties [33]. Parents were asked to rate 26 discipline practices on a 7-point scale (0=never in my life, 1= not in the past year, but it has happened before, 2= 1-2 times a year, 3=several times a year/3-5 per year, 4=monthly or bimonthly/6-12 per year, 5=several times a month/13-50 per year, 6= once a week or more often/more than 50 per year). Three subscales, Mild Physical Discipline (10 items, α =.67), the Severe Physical Discipline (6 items; α =.71) and Psychological Discipline (9 items, α =.63) were used.

Parent Involvement in Education was assessed using 2 items. Parents were asked to rate how often they help their child with school-type activities (e.g., reading or discussing a story together, working on a project together) on a 7-point scale (1 = never, 4 = a few times per month, 7 = everyday). They were also asked to rate the number of total hours they help their child with any education related activities (e.g., spend time talking about school activities, doing homework, reading together) in the last two school days (1 = less than 0.5 hour, 4 = 1.5 - 2 hours, 7 = 3 or more hours). The two items were correlated (r = .51, p <.001); therefore, we combined the items into one scale (α =.67).

Child Functioning

Three tools were used to assess child health and development. The Social Competence Scale (12 items; e.g., “shares things with others,” “copes well with failure”; α = .88; [34, 35] evaluates children’s positive social behaviors, including emotion regulation, prosocial behaviors, and communication skills. Parents were asked to rate how well the statements describe their child on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very well).

Child Health was measured with two global items. Parents were asked to rate their overall perception of their child’s health on a 4-point scale (1 = poor health; 4 = very good or excellent health) and their perception about their child’s tendency to get physical illness on a 3-point scale (1 = certainly true, 3 = not true). Both items are highly related (r = .67); therefore, we created a sum score. A higher score indicates better health.

The Pictorial Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PPSC) [36–39], a pictorial version of PSC that contains pictorial description in addition to written text, assesses early symptoms of behavioral problems. Parents rated how well each statement describes their child on a three-point scale from 0 (never) to 2 (often). The measure has shown to have adequate internal consistency and concurrent validity (associated with Child Behavioral Checklist in expected ways [36, 40, 41]. For this study, three problem scales and the total problem scale were used— Internalizing Problems (5 items; α =.73; e.g., “Feels sad, unhappy” and “Worries a lot”), Externalizing Problems (7 items; α =.69; e.g., “Fights with other children” and “Teases others”), Attention Problems (5 items; α =.71; e.g., “Distracted easily” and “Act as if driven by a motor”), and Total Problems (17 items; α =.77). A screen can be considered positive based on total and domain cut off scores recommended by Blucker et al [42]. Positive screens are determined by a total score > 14, an internalizing score > 4, an externalizing score > 6, or an attention score > 6. A positive screen suggests that a child is at-risk and warrants follow-up to determine potential diagnosis and treatment recommendations.

Inter-correlations among key study constructs are presented in Table 1. Inter-correlations within domains (i.e., parental wellbeing, parenting, child outcomes) and across domains were in expected directions, suggesting support of concurrent and construct validity of study measures for use in Ghana. For example, three parent discipline subscales were positively related to parent discouragement of emotion socialization (r=.25-.35, p <.001). Also, mild physical abuse and psychological abused were positively associated with parent belief about use of corporal punishment (r=.32-.35, p <.001) and conflicted parent-child relationship (r=.37-.43, p <.001).

Demographics

To consider potential confounders, parent and child gender (0=female, 1=male), parental education (0=primary or less, 1=secondary or higher), employment status (1=yes, 0=no), and number of children at home were included in analyses as covariates.

Analyses

To study the relationships between parental wellbeing, parenting, and child behavioral and physical health, we utilized Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), allowing for (a) path analysis of the model in its entirety including mediating mechanisms, (b) correlations between all model variables within each domain (parental wellbeing, parenting, child behavioral and physical health); and, (c) adjustment for potential confounders (i.e., parent and child gender, education, employment, and number of children in the home). Mplus 7 was used for SEM with robust Huber-White estimation algorithms to address nonnormality and variance heterogeneity in addition to use of Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). The fit of the SEM models were evaluated using chi-square (χ2 > .05 or χ2/df ratio less than 3.0), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08), and comparative fit index (CFI > .95) [43].

RESULTS

Parental Wellbeing and Associations with Parenting and Child Functioning

Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of variables pertaining to parental well-being, parenting, and child behavioral and physical health are shown in Table 1. Using the cut-offs recommended by Blucker et al. [42], approximately 10% of the study children were at-risk for mental health problem (with 13% at-risk for attention problem, 5% at-risk for internalizing problem, and 16% at-risk for externalizing problem). For children from high risk communities, prevalence of their mental health problem was higher than children from normal communities (high vs. low risk: 14% vs. 6% for total problems and 9% vs. 2% Internalizing problems, ps<.05). These findings were somewhat comparable to the findings based on sub-Saharan African child populations (which estimated 3% to 29 % of children with problem behaviors using non-PPSC measures)[44].

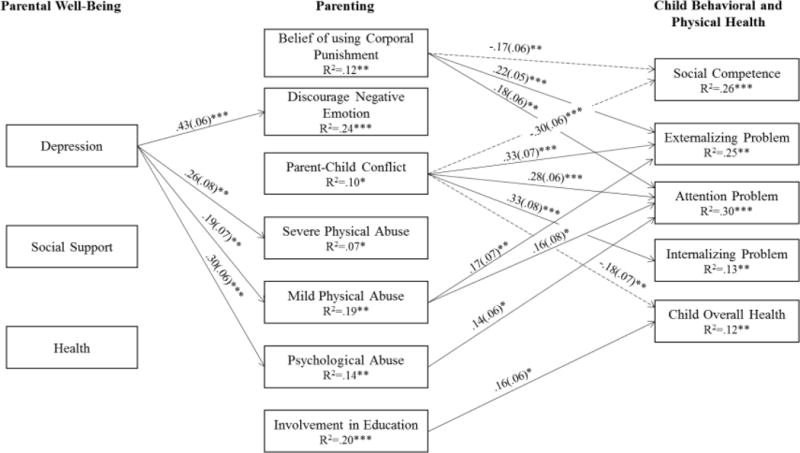

To test the mediational mechanisms (examining whether the influence of parental wellbeing on child health/development is through parenting mediators), adjusted SEM was carried out. Figure 1 presents the standardized path coefficients for the significant paths and the R2 values for each endogenous variable (parenting, and child functioning). Overall, we found a support of the mediational model. Global fit indices of the SEM model pointed to good model fit (χ2 (23) = 38.02, p = .03; χ2/df ratio= 1.6; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05; 95% CI: .02, .08). Furthermore, focused fit indices (standardized residuals and modification indices) revealed no theoretically meaningful points of stress on the model. Parental depression and 5 parenting constructs explained 12-30% of the variance in child behavioral and physical health outcomes. Findings indicated that heightened parental depression is significantly associated with increased discouragement of negative emotion, severe and mild physical abuse, and psychological abuse. Greater mild physical abuse was associated with increased attention and externalizing problems of the children, and greater psychological abuse was associated with increased attention problems of the children.

Figure 1. Structural Equation Modeling for Association among Parental Wellbeing, Parenting, and Child Functioning.

Note. Model controlled for parent gender, education, employment, child gender, and number of children at home. Standardized path coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses) are presented. A dash path indicates a negative association. Paths that did not reach significance are not shown in this figure. * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

Joint significant tests (i.e., Sobel tests) were further carried out to test significant mediational chains for the paths that showed significant associations between parental wellbeing and parenting, and between parenting and child outcomes [45]. We found trend mediational paths for parental depression → mild physical abuse → child externalizing problems and attention problems, Sobel test = 1.81, p = .070 for externalizing problem and Sobel test =1.75, p = .08 for attention problem, respectively. Additionally, we found significant mediational paths for parental depression → psychological abuse → child attention problems, with Sobel tests = 2.11, p = .03.

Although parental wellbeing was not associated with parent-child conflict, several parenting domains, such as belief of using corporal punishment and parental involvement in child’s education, were related to child outcomes in expected ways. We found that greater conflicted relationship and belief in using corporal punishment were associated with lower child social competence and more externalizing and attention problems. High parent-child conflict was also associated with more child internalizing problem and poor overall health. Similarly, high parental involvement in child’s education was associated with better child health.

DISCUSSION

This study extends the parenting literature in Ghana and studies the influence of parental wellbeing and parenting contexts on young children’s development. This study is unique in that there is a focus on early childhood and an investigation of multiple domains of parenting, caregiver wellbeing, and child development that are commonly targeted in early childhood interventions and child development research. In addition, we tested a Family Stress Model that is highly relevant to LMIC contexts and are contributing to understandings of whether the developmental theory developed from Western perspectives is generalizable to Ghana contexts. This study is also one of the few studies that examine parenting and early childhood development specifically in low-and middle-income African countries.

Consistent with the Family Stress Model and findings reported in high income countries, Ghanaian parents’ depression was associated with negative parenting (including practice of more abusive parenting) and in turn increased risk of poor child behavioral health. Similar to other parenting research, we also found parent-child conflict, belief of using corporal punishment, and parental involvement in child’s education to be related to child physical and mental health outcomes in expected ways. Findings suggest cross-cultural consistency regarding developmental mechanisms for optimal child development [26, 46, 47], and suggest that existing evidence-based early interventions and parenting interventions developed from high-income countries [29, 48] might be applicable to Ghanaian families.

Although most of the significant paths identified in the SEM model were consistent with the literature, there were two exceptions. In the model, we did not find expected associations between parent emotional socialization and child outcome measures as suggested in the literature [46, 49], yet in the zero-order correlation results, we found that high parental discouragement of negative emotion, including punishment and neglect of sadness and anger, is associated with high externalizing problem and poor overall health. It is likely that discouragement of negative emotion overlapped with other parenting constructs, such as psychological abuse (r= .34 in this study sample), low parental involvement (r=.23), and parent-child conflict (r=.19); and after adjusting for other parenting constructs, discouragement of negative emotion may play a less important role in child development. In addition, we did not find expected associations between severe physical abuse and child outcome measures in the model or in the zero-order correlations [50]. This may have been due to low rates of severe abuse observed/reported in our community sample.

In light of the findings, there are some limitations worth noting. First, we cannot exclude the potential for reverse causality because this was a cross-sectional study design. In addition, the measures were based solely on single parental self-report, and parent self-report on only global items of child health. There is a lack of alternate/secondary caregiver ratings of child behaviors. Estimation bias due to a single information source cannot be excluded, and caution for the interpretation of the results is warranted. Furthermore, the subsamples of families (e.g., small sample for mothers, fathers, and non-birth caregivers, representing n = 167, 65, and 30 respectively) were not large enough to test mechanisms separately by subgroups, particularly to better understand roles of male and female caregivers in patriarchal African societies. Future studies should apply larger samples to explore differential impacts of mothers and fathers in child development.

Clinical Implications

Findings from this study have implications for prevention and the development and adoption of existing evidence-based interventions for Ghanaian children and families. Specifically, this study identified multiple stressors (e.g., parental depression, poor health, and low social support) and risk factors (e.g. conflicted parent-child relationship, low parental involvement, discouragement of sad and anger negative emotion expressions, and physical and psychological abuse) are related to poor child health and mental health. Findings imply that existing evidence-based family interventions that effectively engage parents and targeted these family and parenting risks may hold promise for the prevention of mental health problems and promotion of healthy development in Ghanaian children. For example, programs such as ParentCorps [15, 26, 28, 51], Positive Parenting Program (Triple P) [52, 53], and the Incredible Years (IY) [54–57] have been successfully implemented and demonstrated intervention effectiveness on parenting and child mental health in both developed and developing countries may be promising for implementation with high-risk Ghanaian children and families. In addition, given low rate of Ghanaian parents’ involvement in early childhood education (i.e., only 33% read to their young child in the previous three days compared to 83% in developed country/US) [3], additional strategies may need to be developed in order to promote Ghanaian parents’ positive attitude and involvement in early childhood care.

SUMMARY.

Most developmental theories, parenting constructs, and early childhood interventions have been developed based on samples from high-income countries, and have not been validated in most African populations. Given high rates of poor early childhood development in LMICs, it is critical to better understand mechanisms to inform parenting interventions. This study addresses gaps in the literature and adds new evidence and understandings of parenting and early childhood development literature in LMIC contexts. Specifically, this study found that multiple parenting constructs developed from high-income countries are generalizable to Ghanaian contexts (e.g., demonstrated to have adequate reliability and validity). The Family Stress Model and mediational mechanisms (the link between parental wellbeing and child outcomes is mediated through parenting) are also supported in Ghanaian families. Our findings have implications for prevention and the development and adoption of existing evidence-based programs for Ghanaian children and families. Future research may focus on how to adapt existing evidence-based interventions to fit local community contexts and service settings.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NYU CGPH Research Affinity Group Challenge Grant/NYU Provost Office and National Institutes of Mental Health (U19 MH110001-01). We wish to acknowledge the generous participation of the schools, community leaders and parents.

References

- 1.Shonkoff J. Science, policy and practice: three cultures in search of a shared mission. Child Dev. 2000;71:181–187. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. Ghana: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (summary of key findings) UNICEF; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoy DC, et al. Early Childhood Developmental Status in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: National, Regional, and Global Prevalence Estimates Using Predictive Modeling. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doku PN. Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children’s psychological wellbeing. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiawoo DK. Some patterns of foster care in Ghana. In: Oppong C, editor. Marriage and fertility and parenthood in West Africa: Changing African Family Monographs. Australia National University Press; Canberra: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goody E. Parenthood and Social Reproduction: Fostering and occupational roles in West Africa. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oppong C. Some biosocial Aspects of Childcare in Ghana: Decades of Change. In: Oppong C, Badasu D, Waerness K, editors. Childcare of a Globalising World Perspectives from Ghana. BRIC; Norway: 2012. pp. 38–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Therborn G. African families in a global context. Nordic Africa Institute; Uppsala: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nukunya GK. Tradition and change in Ghana: An introduction to sociology. 2nd Ghana Universities Press; Accra: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachan M. Constructs of Parenting in Urban Ghana. University of Ghana; Ghana: 2012. Paper 8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ofosu-Asiamah D. Examining the effects of parenting styles on academic performances of Senior High School students in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality, Ashanti region. Kwame Nkrumah University; Ghana: 2013. Unpublished Dissertation Submitted to the. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bornstein MH, Putnick DL. Cognitive and socioemotional caregiving in developing countries. Child Dev. 2012;83:46–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Heatherington EM, editors. Family transitions. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 111–164. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salaam B, Mounts NS. International note: Maternal warmth, behavioral control, and psychological control: Relations to adjustment of Ghanaian early adolescents. J Adolesc. 2016;49:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marbell KN, Grolnick WS. Correlates of parental control and autonomy support in an interdependent culture: A look at Ghana. Motiv and Emot. 2013;37:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo N, et al. Mental health related determinants of parenting stress among urban mothers of young children - Results from a birth-cohort study in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conger RD, et al. Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLoyd VC, Vonnie C. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53(2):185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. 53:185-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic Status, Family Processes, and Individual Development. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alegria M, et al. Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: Integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:270–288. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams JB. The PHQ-9 validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfizer I. PHQ-9(Patient Health Questionnaire) Pfizer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akena D, Joska J, Obuku EA, Stein DJ. Sensitivity and specificity of clinician administered screening instruments in detecting depression among HIV-positive individuals in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1245–1252. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.764385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakigudde J, Musisi S, Ehnvall A, Airaksinen E, Agren H. Adaptation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in a Ugandan setting. Afri Health Sci. 2009:S35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang K-Y, Abura G, Theise R, Nakigudde J. Parental depression and associations with parenting and children’s physical and mental health in Sub-Saharan African settings. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;48:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0679-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang K-Y, Cheng S, Calzada E, Brotman LM. Symptoms of anxiety and associated risk and protective factors in young Asian American children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43:761–774. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0295-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brotman LM, et al. Promoting effective parenting practices and preventing conduct problems among ethnic minority families from low-income, urban communities. Child Dev. 2011;82:258–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang K-Y, et al. Applying public health frameworks to advance the promotion of mental health among Asian American children. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014;5:145–152. doi: 10.1037/a0036185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson-McClure S, et al. A population-level approach to promoting healthy child development and school success in low-income, urban neighborhoods: impact on parenting and child condut problems. Prevention Science. 2015;16:279–290. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0473-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Neal C, Magai Do parents respond in different ways when children feel different emotions? The emotional context of parenting Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:467–487. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pianta RC. Child-Parent Relationship Scale. Charlottesville: University of Virginia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Runyan DK, et al. The development and piloting of the ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool-Parent Version (ICAST-P) Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrigan A. Social Competence Scale - Parent Version, Grade 1 / Year 2 (Fast Track Project technical report) 2002 (Available from the Fast Track Project Web site, http://www.fasttrackproject.org/)

- 35.Gouley KK, Brotman LM, Huang K-Y, Shrout P. Construct validation of the social competence scale in preschool-age children. Social Development. 2008;17:380–398. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leiner MA, Balcazar H, Straus DC, Shirsat P, Handal G. Screening Mexican for psychosocial and behavioral problems during pediatric consultation. Rev Invest Clin. 2007;59:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiner MA, Puertas H, Caratachea R, Perez H, Jimenez P. Sensitivity and specificity of the pictorial Pediatric Symptom Checklist for psychosocial problem detection in a Mexican sample. Rev Invest Clin. 2010;62:560–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leiner MA, Rescorla L, Medina I, Blanc O, Ortiz M. Psychometric comparisons of the pictorial child behavior checklist with the standard version of the instrument. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:618–627. doi: 10.1037/a0019778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakigudde J, Bauta B, Wolf S, Huang K-Y. Screening Child Social Emotional and Behavioral Functioning in Low-Income Country Contexts. Jacobs Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science. 2016;2:016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoppelbein L, Greening L, Moll G, Jordan S, Suozzi A. Factor analyses of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 with African-American and Caucasian pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37:348–357. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canceko-Llego CD, Castillo-Carandang NT, Reyes AL. Validation of the Pictorial Pediatric Symptom Checklist – Filipino version for the psychosocial screening of children in a low-income urban community. Acta Med Philipp. 2009;43:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blucker RT, et al. Pediatric behavioral health screening in primary care a preliminary analysis of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 with functional impairment items. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014;53:449–455. doi: 10.1177/0009922814527498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cortina MA, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG. Prevalence of child mental health problems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:276–281. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang K-Y, Calzada E, Cheng S, Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Brotman LM. Cultural Adaptation, Parenting and Child Mental Health Among English Speaking Asian American Immigrant Families. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;48:572–583. doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0683-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calzada E, Huang K-Y, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, Brotman LM. Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Culture Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:285–296. doi: 10.1037/a0028694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.UNODC. Compilation of Evidence-Based Family Skills Training Programmes. United Nations Publication; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedlmeier W, Corapci F, Cole PM. Emotion Socialization in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5:410–427. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macfie J, Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Dissciation in maltreated versus nonmaltreated preschool-aged children. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brotman LM, et al. Effects of ParentCorps in pre-kindergarten on child mental health and academic performance: follow-up of a randomized clinical trial through 8 years of age. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanders MR. Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:506–517. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sumargi A, Sofronoff K, Morawska A. A Randomized-Controlled Trial of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program Seminar Series with Indonesian Parents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46:49–761. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Webster-Stratton C. The incredible years: Parents, teachers, and children training series. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2001;18:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Stoolmiller M. Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: evaluation of the Incredible Years Teacher and Child Training Programs in high-risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2008;49:471–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumann AA, et al. Cultural Adaptation and Implementation of Evidence-Based Parent-Training: A Systematic Review and Critique of Guiding Evidence. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;53:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Menting ATA, de Castro BO, Matthys W. Effectiveness of the Incredible Years parent training to modify disruptive and prosocial child behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]