Abstract

In this article, we discuss theory and research on how people who have different adult romantic attachment orientations fare across one of life’s often happiest, but also most chronically stressful, events—the transition to parenthood. We first discuss central principles of attachment theory and then review empirical research revealing how two types of attachment insecurity—anxiety and avoidance—tend to prospectively predict unique patterns of relational and personal outcomes across this often challenging life event. We also suggest how many of these findings can be understood within a diathesis-stress process model that has guided our own research on the transition to parenthood.

Keywords: Attachment, attachment orientations, transition to parenthood, parenting, chronic stress

Few events are more life-changing than becoming a parent for the first time [1]. Until recently, most research investigating the transition to parenthood has been primarily descriptive, focusing on typical (modal) outcomes and experiences for new mothers and, less often, new fathers [2]. During the past 20 years, however, researchers have begun applying principles of attachment theory [3,4,5,6] to better understand not only modal responses to having a first child, but how and why certain individuals react very differently to this challenging life event. Bowlby [6] believed that the transition to parenthood is a time when attachment processes are activated and salient, partly because it is a chronically stressful time, but also because it elicits perceptions and memories of how individuals were treated by their own parents during their childhood.

For several years, we [7] have studied how individuals who have secure versus insecure attachment orientations think, feel, and behave both prenatally and postnatally across the transition to parenthood. Borrowing key attachment principles, we conceptualize attachment insecurity as a diathesis capable of generating maladaptive interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes in response to this life transition.

Principles of Attachment Theory

According to Bowlby [3,4,5], the attachment system evolved to increase the survival of infants and children in our ancestral past. The attachment system activates (turns on) when individuals experience fear, anxiety, or other forms of distress. From an evolutionary perspective [8], the system promoted survival by keeping children in close physical proximity to their attachment figures. From a psychological perspective [9,10], proximity reduces fear, anxiety, and distress, allowing individuals to pursue other important life tasks. The attachment system shuts down (turns off) when individuals experience a sufficient reduction in fear, anxiety, or distress, indexed by felt security [11].

Across development, individuals keep track of the extent to which they receive sufficient proximity/comfort from their attachment figures, beginning with their parents and continuing with their close friends and romantic partners [12]. These representations, known as working models [4], have two components: (1) a model of attachment figures (e.g., parents, close friends, romantic partners), which includes their degree of responsiveness to one’s prior bids for proximity/comfortable, and (2) a model of self, which entails information about one’s ability to obtain proximity/comfort and one’s value as a relationship partner.

Bowlby [4,5] proposed that the way in which individuals are treated by significant others—especially during times of stress—shapes their expectations, attitudes, and beliefs about future partners and relationships. These expectancies/attitudes/beliefs operate as “if/then” propositions (e.g., “If I am upset, then I can count on my partner to support me” [13]. Once developed, working models affect how individuals relate to their romantic partners in interpersonal contexts, especially in stressful/threatening situations. Nevertheless, working models can and sometimes do change, especially when individuals encounter experiences that directly contradict their current models [14,15].

Adult Attachment Orientations

Adult romantic attachment orientations are assessed on two relatively uncorrelated dimensions labeled avoidance and anxiety [16,17]. Avoidance reflects the degree to which individuals feel comfortable with closeness and emotional intimacy in relationships. Highly avoidant people harbor negative views of their romantic partners and positive, but sometimes unstable, self-views [18]. They strive to establish and maintain independence, control, and autonomy in their relationships [19,20], because they believe that seeking psychological/emotional proximity is neither possible nor desirable based on their history of repeated rejection. These beliefs motivate avoidant people to use distancing/deactivating coping strategies [20,21] in which they suppress negative thoughts/emotions and attachment needs in order to maintain independence and autonomy. Less avoidant (or more secure) individuals are comfortable with intimacy and mutual dependence.

Anxiety indexes the degree to which individuals worry about not being appreciated or being abandoned by their romantic partners. Highly anxious individuals are heavily invested in their relationships, and they yearn to become emotionally closer to their partners in order to feel more secure [19]. They have negative self-views and guarded (but often hopeful) views of their partners [18]. These conflicting views lead anxious individuals to question their worth, worry about relationship loss, and remain hypervigilant to signs their partners might be withdrawing [21]. To boost their low security, anxious individuals frequently behave in ways that smother or pressure their partners for reassurance [22]. Because they do not know whether they can count on their partners, anxious people rely on emotion-focused/hyperactivating coping strategies [20,21], which sustain or escalate their worries and keep their attachment systems activated [20,23]. Less anxious (or more secure) individuals do not worry about loss or abandonment.

The Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model and the Transition to Parenthood

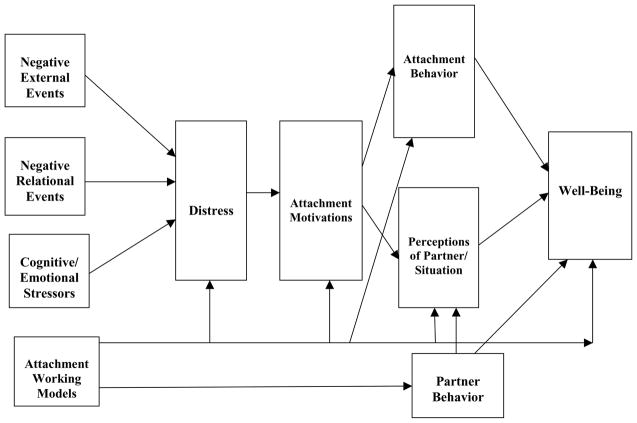

The findings of many attachment/transition to parenthood studies can be understood within the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model [7], which is shown in Figure 1. According to this model, the two types of attachment insecurity act as a diathesis that produces negative interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes in response to perceptions tied to stressful/threatening events during the transition. Although the model addresses three major forms of stress (external, internal, and chronic), here we focus on chronic stress. Most research has examined two broad outcomes: relational (e.g., marital satisfaction) and personal (e.g., depression).

Figure 1.

The Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model [7] has two components: a normative (species-typical) component, and an individual difference component. From a normative perspective, the attachment system is activated (turned on) by three types of events: (1) negative external events (e.g., dangerous/threatening situations), (2) negative relational events (e.g., relationship conflict, separation, abandonment), and (3) cognitive/emotional stressors (e.g., ruminating about negative events). Each one elicits distress in most people. Distress, in turn, triggers species-typical attachment motivations to seek proximity, support, and/or reassurance from attachment figures (e.g., parents, close friends, romantic partners). These motivations then launch specific attachment behaviors designed to reduce or regulate distress, which then influences perceptions of the partner and/or the current situation. Perceptions of the partner/situation, however, are also influenced by how the partner behaves in the current situation. The specific attachment behaviors that an individual displays, and the partner/relationship perceptions s/he has, are guided by his/her working models (see below). These behaviors and perceptions, in turn, affect an individual’s relational and personal well-being in response to the stressful situation.

Attachment working models can affect any stage of the model, as shown by the lines running from attachment working models to each model stage. For example, working models can influence how distressed individuals feel in response to a negative or stressful event, and they can determine which attachment motivations are evoked when distress is experienced. Working models can also affect the attachment behaviors that individuals display when attachment motivations are triggered, how they perceive their partners in the situation, and how their partners behave toward them. Each of these pathways can impact the quality of relational and personal well-being that is experienced during or after encountering the stressful event.

From an individual difference perspective, the model proposes that individuals who have different attachment orientations should respond differently when they are exposed to certain kinds of distressing situations. For example, when highly anxious individuals encounter stressful events that threaten or call into question the quality or stability of their romantic relationships, they should be keenly aware of their distress and seek immediate help/support from their romantic partners. In light of the conflicted nature of their working models, however, anxious individuals should be strongly motivated to reduce distress by increasing proximity (including emotional closeness) with their partners. This should be exacerbated by their reliance on emotion-focused/hyperactivating coping strategies [7, 21], which direct their attention toward the source of distress and lead them to ruminate about possible negative outcomes. Such coping strategies also direct their attention away from figuring out how to resolve the stressor/problem, which keeps their attachment systems activated. As a result, the attachment behaviors that highly anxious individuals enact center on intense, obsessive proximity/support/reassurance-seeking from their partners, which often do not diminish their distress. Over time, the romantic partners of anxious individuals are likely to tire and become frustrated from continually having to offer reassurance/support, and these reactions may be construed by anxious individuals as signs of further rejection. Highly anxious individuals should also perceive their partner’s intentions, motives, and actions less benevolently during the stressful situation, underestimating the care/support that their partners provide (or are willing to provide). These negative perceptions should, in turn, generate lower relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.

When confronting stressful events, especially those that threatened their autonomy and independence, highly avoidant individuals might not be fully aware of how distressed they are, and they should neither want nor seek help or support from their partners unless they feel overwhelmed. Given their negative, cynical working models, avoidant individuals should be motivated to reduce or contain the distress they feel by being self-reliant, which allows them to reestablish independence, autonomy, and control in the stressful situation. This should be facilitated by their use of avoidant/deactivating coping strategies [7, 21], which suppress awareness of their distress, attachment needs, and attachment behaviors, at least in the short-term. Avoidant individuals should engage in attachment behaviors that allow some contact with their partners, but at a safe, emotionally comfortable distance and on terms they dictate. The partners of avoidant individuals should, in turn, offer and provide lower levels of reassurance and support, which avoidant individuals should prefer, but may also view as further rejection. Avoidant individuals should also view their partner’s intentions, motives, and behaviors in the stressful situation less benevolently, leading them to underestimate the amount of care and support their partners have given them (or are willing to provide). These negative perceptions should culminate in lower relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.

When highly secure individuals (i.e., those who score low on anxiety and avoidance) experience distressing situations, they ought to realize that they are upset and may need help or support from their partners, depending on the nature of the stressor and the knowledge and skills they have to address it. In view of their positive working models, secure individuals should be motivated to manage distress by drawing closer to their partners (physically and emotionally) in order to increase closeness and intimacy with them. This should be facilitated by their adoption of problem-focused coping strategies [7, 21], which permit secure individuals to resolve most problems constructively with appropriate assistance from their partners. The attachment behaviors that highly secure individuals should enact involve requesting or seeking proximity, comfort, or support from their partners, which helps them dissipate distress so they can pursue other important life tasks. The partners of highly secure individuals, in turn, should respond in more positive and constructive ways when secure individuals request comfort/care/support from them (unless their partners happen to be insecurely attached). In addition, highly secure individuals should perceive their partner’s intentions, motives, and actions in the situation more benevolently. These positive perceptions should result in better relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.

The transition to parenthood is an impactful, chronic stressor because new parents must cope with novel challenges, including role changes, chronic fatigue, family demands, financial strain, and work-family conflict. Although some new parents report increases in marital and personal well-being [1], most report downturns in marital satisfaction and personal well-being [2]. We now describe the findings of longitudinal transition studies that have assessed adult romantic attachment orientations.

Relational Outcomes

Most transition research examining relational outcomes has focused on marital satisfaction. Longitudinal studies consistently document that insecure partners—especially highly anxious ones—experience lower and/or more rapidly declining satisfaction following childbirth [2,24–28].

Our research has confirmed and extended these findings, testing specific pathways in the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model (Figure 1). For example, we have found that highly anxious women enter the transition perceiving or expecting less spousal support, and this forecasts steeper declines in their marital satisfaction across the transition [29,30]. Importantly, husbands of more anxious women who feel that they are not getting sufficient support report parallel declines in both satisfaction and support-provision, which may further undermine satisfaction in highly anxious wives. In addition, highly avoidant people—especially men—who believe their newborn is interfering with their personal or work lives [29] or perceive they are doing too much childcare [31] report very steep declines in satisfaction over the first two years of the transition, whereas less avoidant (more secure) men and women do not. These core concerns—insufficient support/relationship loss for anxious people and insufficient independence/autonomy for avoidant people—are precisely those that should activate the attachment systems and working models of these two types of insecure people.

A handful of studies have explored other relational outcomes. For example, insecurely attached people—particularly highly avoidant ones—report greater conflict and partner-targeted aggression across the transition [32–35], most likely in response to the life-altering personal and work changes associated with having a child. Highly avoidant people also report declines in relationship commitment over the transition [36] and have more negative views of their babies [37], even at two weeks postpartum [38]. Both highly avoidant and highly anxious new parents also have less interpersonal empathy and report poorer parental adjustment across the transition [39], but their engagement as parents depends in part on their partner’s attachment orientation/behavior [40]. Lang and colleagues [40], for instance, found that highly avoidant fathers spend more time in exploration-focused engagement with their young children on days when mothers (their wives) display heightened attachment anxiety, whereas highly anxious mothers spend more time in proximity-focused engagement with their young children when fathers (their husbands) exhibit greater avoidance.

Personal Outcomes

Most transition research investigating personal outcomes has targeted depressive symptoms. Longitudinal studies repeatedly reveal that highly anxious and highly avoidant individuals experience elevated and sometimes increasing depressive symptoms over the transition [41–43].

In our work testing the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model, we have found that highly anxious women who enter the transition perceiving or expecting either less spousal support or greater spousal anger report increases in depressive symptoms over time [43,44]. Consistent with our model, we [44] have also found that the link between these interaction effects and pre-to-postnatal increases in depressive symptoms are mediated by wives’ perceived declines in their husbands’ support across time. Moreover, for highly anxious women, the link between their prenatal and postnatal depression scores is mediated by their (wives’) perceptions of support available from their husbands. Additionally, their husbands report increases in their depressive symptoms and declines in their support-provision across the transition, which should exacerbate the depressive symptoms of highly anxious wives.

Consistent with our model, we [43] have also found that: (a) the association between attachment anxiety and depressive symptoms is moderated by variables assessing the quality of their marriages; (b) the association between avoidance and depressive symptoms is moderated by variables indexing the amount of family responsibilities; and (c) the caregiving styles enacted by partners affects depressive symptoms differently in highly anxious and highly avoidant persons.

A few studies have investigated other personal outcomes. Insecurely attached new parents, for example, report greater parental strain and poorer coping [37,45] and less parental reflective functioning [46] across the transition. Moreover, women who enter parenthood seeking less spousal support or who have highly avoidant husbands tend to become more avoidant across the transition, whereas men who report providing more prenatal support to their wives become less avoidant [47]. Among first-time economically-stressed mothers, those who are more stressed, depressed, or received less sensitive care from their own mothers become more insecure over time [48]. Viewed together, these findings are consistent with the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model [7].

Future Directions and Conclusion

There are two especially promising directions for future research. First, under what circumstances do securely attached individuals fail to regulate their emotions well during the transition, and when do insecurely attached individuals regulate theirs more effectively? Second, when are the partners of insecurely attached new parents able to soothe their insecure mates, helping them to react more constructively across the transition [49]? Third, how does attachment disorganization [50] affect the transition? Research done outside of the transition indicates that both men and women with higher disorganized scores show greater anger and behave more aggressively toward their partners. This suggests that aggression, anger, and even abuse, which have rarely been studied in the transition literature, might occur across the transition among disorganized partners.

In conclusion, the transition to parenthood triggers different attachment concerns in highly anxious and highly avoidant people—threats concerning support/loss in anxious persons, and threats concerning autonomy/independence in avoidant persons. Research relevant to the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model has begun to shed clarifying light on the psychological processes through which these concerns translate into lower well-being in these two types of insecure people.

Highlights.

Reviews how adult attachment orientations predict outcomes across the transition to parenthood

Discusses why chronic stress evokes different concerns in anxious and avoidant people

Frames current findings within the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model

Proposes promising directions for future research

Acknowledgments

Some of the research reported in this article was support by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01-MH49599 to Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeffry A. Simpson, University of Minnesota

W. Steven Rholes, Texas A&M University.

References

- 1*.Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change in couples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. A general overview of what the transition to parenthood involves and how new parents typically react to it. [Google Scholar]

- 2**.Feeney JA, Hohaus L, Noller P, Alexander RP. Becoming parents: Exploring the bonds between mothers, fathers, and their infants. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. One of the first comprehensive overviews of how secure, anxious, and avoidant adult romantic attachment orientations are associated with an array of personal and relational outcomes in partners navigating the transition to parenthood. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowlby J. A secure base. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Adult attachment orientations, stress, and romantic relationships. In: Devine PG, Plant A, Olson J, Zanna M, editors. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 45. 2012. pp. 279–328. A detailed description of the Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model and review of studies that provide support for different pathways in the model. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson JA, Belsky J. Attachment theory within a modern evolutionary framework. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marvin RS, Britner AA, Russell BA. Normative development: The ontogeny of attachment in childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Adult attachment and emotion regulation. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2016a. pp. 507–533. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development. 1977;48:1184–1199. doi: 10.2307/1128475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bretherton I, Mulholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory. In: Cassidy J, RShaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins NL, Guichard AC, Ford MB, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment: New developments and emerging themes. In: Rholes WS, Simpson JA, editors. Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford; 2004. pp. 196–239. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arriaga XB, Kumashiro M, Simpson JA, Overall NC. Revising working models across time: Relationship situations that enhance attachment security. Personality and Social Psychology Review. doi: 10.1177/108886317705257. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraley RC. Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:123–51. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan K, Clark C, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Feeney JA. Adult romantic attachment: Developments in the study of couple relationships. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. A comprehensive theoretical and empirical overview of how adult attachment orientations are systematically associated with how people think, feel, and behave in romantic relationships. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikulincer M. Attachment working models and the sense of trust: An exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1209–1224. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2016b. A recent comprehensive and thorough review of all the major lines of research on adult attachment. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 35. New York: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaver PR, Schachner DA, Mikulincer M. Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:343–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins NL, Ford MB, Guichard AC, Allard L. Working models of attachment and attribution processes in intimate relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:201–219. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzeschi C, Pazzagli C, Radi G, Raspa V, Buratta L. Antecedents of maternal parenting stress: The role of attachment style, prenatal attachment, and dyadic adjustment in first-time mothers. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moller K, Hwang CP, Wickberg B. Romantic attachment, parenthood and marital satisfaction. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006;24:233–240. doi: 10.1080/02646830600821272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paley B, Cox MJ, Harter KS, Margand NA. Adult attachment stance and spouses’ marital perceptions during the transition to parenthood. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:340–360. doi: 10.1080/14616730210167276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Settle T, Lee J, Kamp Dush CM. Supportive coparenting relationships as a haven of psychological safety at the transition to parenthood. Research in Human Development. 2016;13:32–48. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2016.1141281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trillingsgaard T, Sommer D, Lasgaard M, Elklit A. Adult attachment and the perceived cost of housework and child care. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2014;32:508–519. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2014.945516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Kohn JL, Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Martin AM, Tran S, Wilson CL. Changes in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: The role of adult attachment orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:1506–1522. doi: 10.1177/0146167212454548. A fairly recent transition study of middle-class couples having their first child. The results focus on how attachment orientations are related to marital satisfaction across the transition, with a focus on key moderating variables. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Campbell L, Grich J. Adult attachment and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:421–435. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.421. One of the first transition to parenthood studies to examine how adult romantic attachment orientations (assessed prenatally) prospectively predict important marital outcomes over the first six months of the transition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Fillo J, Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Kohn JL. Dads doing diapers: Individual and relational outcomes associated with the division of childcare across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015;108:298–316. doi: 10.1037/a0038572. A recent study describing the steep downturns in marital satisfaction that avoidantly attached men who perceive they are doing too much childcare experience across the first two years of the transition to parenthood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bower DJ. Unpublished dissertation. Ohio State University, Dissertation Abstracts International; 2013. Personality, attachment, and relationship conflict across the transition to parenthood. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gou LH, Woodin EM. Relationship dissatisfaction as a mediator for the link between attachment insecurity and psychological aggression over the transition to parenthood. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2017;6:1–17. doi: 10.1037/cfp0000072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rholes WS, Kohn JL, Simpson JA. A longitudinal study of conflict in new parents: The role of attachment. Personal Relationships. 2014;21:1–21. doi: 10.1111/pere.12023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eller J, Marshall EM, Simpson JA, Karantzas GC, Rholes WS. Partner predictors of marital aggression across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferriby M, Kolita L, Kamp Dush C, Schoppe-Sullivan S. Dimensions of attachment and commitment across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29:938–944. doi: 10.1037/fam0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krause K. Unpublished dissertation. Eastern Michigan University, Dissertation Abstracts International; 2014. Relationship predictors of prenatal maternal representations and the child and parenting experiences one year after birth. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson CL, Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Tran S. Labor, delivery, and early parenthood: An attachment theory perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:505–518. doi: 10.1177/0146167206296952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazmierczak M. Couple empathy: The mediator of attachment styles for partners adjusting to parenthood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2015;33:15–27. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2014.974148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang SN, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Kotila LE, Kamp Dush CM. Daily parenting engagement among new mothers and fathers: The role of romantic attachment in dual-earner families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:862–872. doi: 10.1037/a0034510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feeney J, Alexander R, Noller P, Hohaus L. Attachment insecurity, depression, and the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:475–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-6811.2003.00061.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meuti V, Aceti F, Giacchetti N, Carluccio GM, Zaccagni M, Marini I, Giancola O, Ciolli P, Biondi M. Perinatal depression and patterns of attachment: A critical risk factor? Depression Research and Treatment. 2015;2015:105012. doi: 10.1155/2015/105012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43**.Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Kohn JL, Wilson CL, Martin AM, Tran S, Kashy DA. Attachment orientations and depression: A longitudinal study of new parents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:567–586. doi: 10.1037/a0022802. A fairly recent transition study of first-time parents (both partners) that focuses on depressive symptoms across the first two years of the transition to parenthood. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Tran S, Wilson CL. Adult attachment, the transition to parenthood, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1172–1187. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1172. One of the first transition studies to investigate how adult attachment orientations predict depressive symptoms in women and men across the first six months of the transition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexander R, Feeney J, Hohaus L, Noller P. Attachment style and coping resources as predictors of coping strategies in the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships. 2001;8:137–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2001.tb00032.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cristobal PS, Santelices MP, Fuenzalida DAM. Manifestation of trauma: The effect of early traumatic experiences and adult attachment on parental reflective functioning. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Wilson CL. Changes in attachment orientations across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:317–331. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00030-1. One of the first studies to explore how adult attachment orientations prospectively predict depressive symptoms in men and women during the first six months of the transition. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern JA, Fraley RC, Jones JD, Gross JT, Shaver PR, Cassidy J. Developmental processes across the first two years of parenthood: Stability and change in adult attachment styles. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/dev0000481. (in press) doi:10/1037/dev0000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49*.Simpson JA, Overall NC. Partner buffering of attachment insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:54–59. doi: 10.1177/0963721413510933. A process model suggesting what the partners of highly anxious and highly avoidant individuals can do to reduce the likelihood that their insecure partners think, feel, and behave in dysfunctional ways during interpersonal conflicts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Paetzold RL, Rholes WS. Disorganized attachment in adulthood: Theory, measurement, and implications for romantic relationships. Review of General Psychology. 2015;19:146–156. A recent review and synthesis of disorganized attachment in adults, including how it is measured and expressed in romantic relationships. [Google Scholar]