Abstract

The facial nerve is unique among the motor nerves. It has long and tortuous course through the temporal bone and within the Fallopian canal. Because of this it is more prone to paralysis than any other nerve in the body. The most frequent type of facial palsy is Bell’s palsy. This is an acute idiopathic lower motor neuron palsy of the facial nerve which does not normally progress and which is most usually unilateral and self limiting,: the majority of cases remit within 4–6 months and nearly always remission is complete by 1 year. In those cases that do not recover it is my contention that this is caused by Either the progression, or after effects, of secondary ischemia: tertiary ischemia. In turn this causes thickening of the facial nerve sheath with a fibrous band or bands forming with resultant strangulation and compression of the nerve, which hampers its recovery. In such cases facial nerve decompression with slitting of the sheath and cutting of any fibrous bands would be the preferred management when allied with aggressive medical therapy.

Keywords: Bell’s palsy, Tertiary ischemia, Residual facial palsy

Aetiology

There are three theories advanced regarding the aetiology of Bell’s palsy which is thought to be due either to vascular change or to a viral aetiology. In some cases there is also a hereditary origin. There are certain features that support surgical decompression of the facial nerve in selected cases. In this paper I describe tertiary ischemia with fibrous thickening, in which surgical decompression of the nerve with slitting of the sheath and cutting of any fibrous band or bands, if present, was an important part of treatment. It is my contention that the thickened facial nerve sheath and the associated bands cause strangulation and compression of the nerve, and that timely decompression serves to promote regeneration.

The nerve is a layered structure with an outer tough shiny grey periosteal layer and an immediately deeper layer formed by a vascular plexus and covering the epineural layer of the neural tissue. Peripherally this vascular plexus is formed by the stylomastoid artery and then this in turn is replaced, more centrally, by the petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery, the internal auditory artery and the anterior inferior cerebral artery. The presence of the vascular layer is clearly important since when it is compromised, local ischemia and a palsy will result.

It seems that vascular ischaema can be of three types.

Vascular Theory

Primary Ischemia

The facial nerve has tough epineurium which has rich vascular supply. Vasospasm will lead to decreased blood supply. Resulting in a primary ischaemic neuropathy. This is a rare occurrence. And opponents of this theory would state that the nerve has adequate blood supply with numerous anastomoses between the stylomastoid and petrosal vessels. However in certain cases, such as in Leriche’s syndrome and possibly Diabetes mellitus [1] such a mechanism could apply. It is certainly possible, as is witnessed by the onset of acute facial paralysis following the embolisation of the middle meningeal artery [2]. Some also believe that there is a lack of significant anastomosis between the stylomastoid and petrosal branches [3]: this would pre-dispose to ischaemia at this point.

Secondary Ischemia

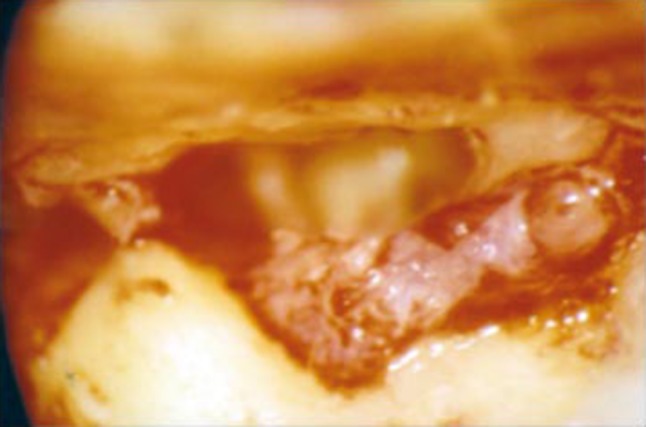

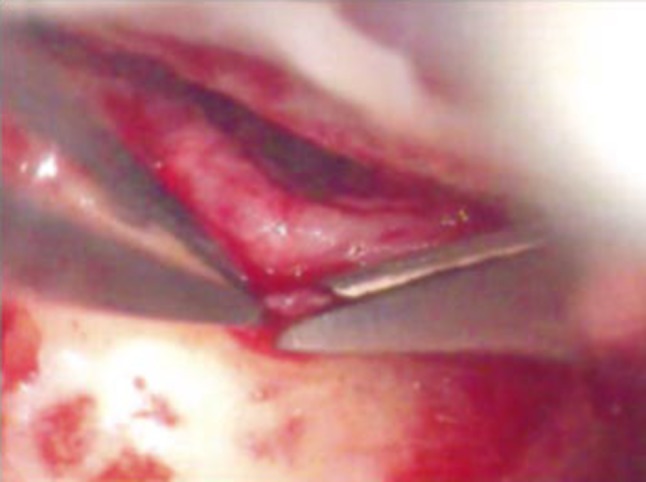

Hilger [4] proposed that a process of primary ischemia could lead to secondary ischemia. The essential features in such cases are an initial arteriolar constriction followed by capillary dilatation with an increase in permeability and resultant transudation. The lymph capillaries are compressed by the presence of the transudate and may even close. This further increases the formation of transudate and leads to zonal ischemia: a vicious cycle therefore arises which may even result in necrosis of the nerve thus may lead to discontinuty of the nerve [4] I have even seen affection of fallopian canal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative photograph of facial nerve decompression-Markedly thickened facial nerve sheath strangulating the facial nerve with erosion of fallopian canal. Note the edema of nerve

The pathophysiology of edema within the confines of fallopian canal is the same Initial vasospastic changes increase capillary permeability and the formation of oedema, which is aided and abetted by histamine release mechanism from an intermediate hypersensitivity reaction. According to Sunderland [5] there is a delicate balance of the pressures within the fallopian canal which are necessary for continued nutrition of the nerve: this is now disturbed. Any slight swelling of the nerve then leads to obstruction of the venous outflow which, in turn, also promotes a viscous cycle that results in interference with the arterial blood supply of the nerve.

Tertiary Ischemia

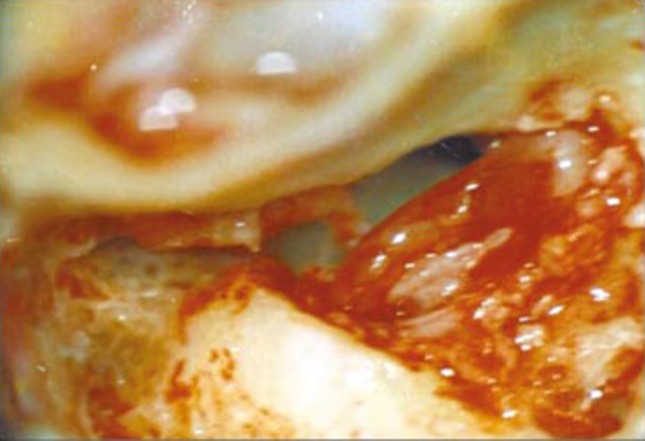

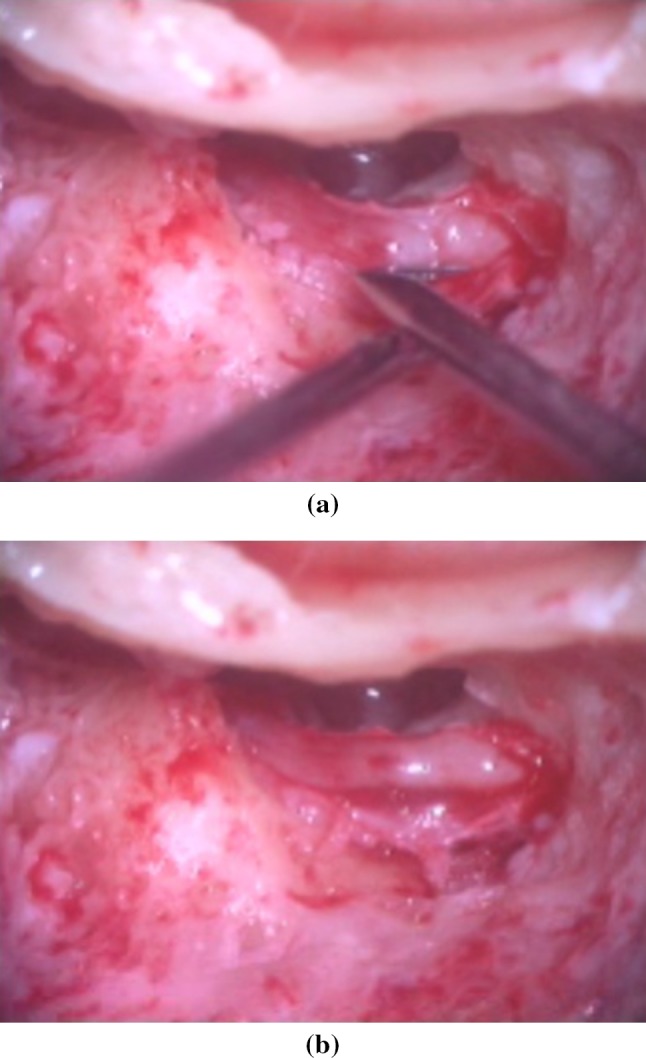

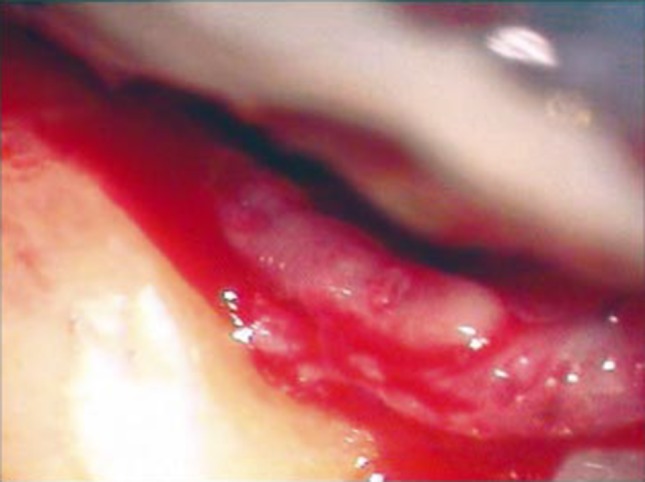

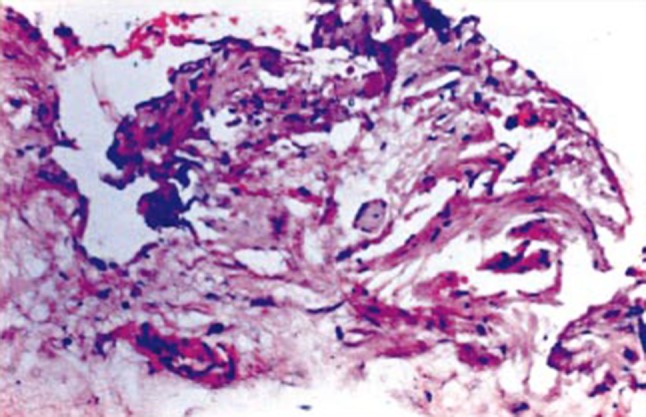

I believe that in certain cases the process of secondary ischemia leads on to, or progress to, tertiary ischemia [6, 7]. This is the result of the vasospasm progressing and leading to periarteritis and endarteritis of the blood vessels leading to varying amount fibrosis of facial nerve sheath. This results in thickening of the facial nerve sheath and at times also to the formation of fibrous tissue causing strangulation of the facial nerve. At this stage surgically decompression with slitting of the sheath and cutting of any fibrous bands if present is important as otherwise it can result in permanent facial palsy (Figs. 2, 3, 4). In cadaveric dissection it is not possible to take a big biopsy of the sheath as it is very thin and fragile and histopathology is unsatisfactory. However in Bell’s palsy it is possible to comfortably take an adequate biopsy of the sheath for reporting as the sheath is very much thickened. When this is done the microscopic features include the presence of blood vessels with thickened walls along with changes of obliterative endarteritis. There is also fibrosis. Figures 5 and 6 I have seen even erosion of the bone of the fallopian canal in such cases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative photograph of facial nerve decompression—thickening of facial nerve sheath due to fibrosis and edema at stylomastoid foramen. Facial nerve sheath is slit open

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photographs of facial nerve decompression showing. a A fibrous band strangulating facial nerve. b Fibrous band is cut. Note the compression it has caused on facial nerve

Fig. 4.

Inraoperative photograph of facial nerve decompression. Note -marked edema of facial nerve there were multiple bands formation which were cut-note indentations caused by them. There is markedly thickened facial nerve sheath

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative photograph of facial nerve decompression—Biopsy being taken of thickened facial nerve sheath

Fig. 6.

Histopathology of facial nerve sheath showing bundles of facial nerve fibers with fibrosis (H&E Staining ×20)

Such changes in facial nerve sheath architecture are typically seen in cases that have a residual facial palsy and the histopathological changes can be well demonstrated by Masson’s trichrome staining When a facial nerve decompression is done in such cases and the sheath is slit then almost immediately the patient notices a relief of the tightness felt in and around the mastoid area—but recovery of facial paralysis is not, of course, immediate.

Viral Theory

This theory proposes that Bell’s palsy may be a part of polyneuropathy of viral origin. The viruses most incriminated are Herpes Zoster or Simplex virus [8, 9], but it has been also reported that by Herpes Simplex Virus type -1 (H S V-I) is a causative agent in Bell’s paralysis [10]

It is proposed that the virus replicates in the ganglion cells causing local damage and hypofunction of the nerves. It is then thought to pass down to the axons, causing a radiculitis, and to infect Schwann cells causing inflammation and an autoimmune response. Lymphocytic infiltration would then follow leading to fragmentation of myelin with demyelination and chromatolysis. When the inflammation and autoimmune reaction resolves remyelination would then follow. However studies of nerve sheath fails to reveal inflammatory cells [11, 12] and such data would not therefore support an inflammatory etiology for Bell’s Palsy.

Hereditary Theory

Familial anatomic variations in the middle ear cleft are common occurrences.

They can be classified as being due to.

Variations of Pneumatisation

It is well known that pneumatisation of the mastoid varies from a sclerotic (acellular) form to being well pneumatised. In chronic suppurative otitis media, Cholesteatoma primarily occurs in sclerotic or acellular mastoid. There can be associated variations of fallopian canal.

Mastoid Antrum

This also varies in size from small to vary large sized which can lead to formation of retraction pockets of tympanic membrane with cholesteatoma. This is because a large sized mastoid antrum can cause more negative pressure when the eustachian tube is blocked [6, 13].

Facial Canal

The canal has a long and tortuous course in the temporal bone and is prone to variations in one of three ways –diameter, course and dehiscence. Dehiscence is the most common. A familial anatomic variation in the facial canal may account for tendency towards greater incidence of development of Bell’s palsy latter in life. The bony constriction of the fallopian canal leads to acute recurrent attacks of facial palsy which is more common in osteoporotic group of diseases as the fallopian canal in them is of a abnormally small diameter. This is believed to make the nerve more prone for primary ischemic injury or even viral infection. The trait of development of recurrent attacks of facial palsy is believed to be recessive [14].

The diameter of the fallopian canal at the metal foramen near the fundus is 0.61 mm [15] but accordingly is also suggested it be of 0.68 mm [16]. There it is suggested that this is the narrowest part of fallopian canal and should be attended to while decompressing the nerve.

Observations

I have experience of 614 cases of facial nerve decompressions for various conditions (Table 1). Out of these, most cases (469) were performed while treating chronic suppurative otitis media with cholesteatoma. A further 87 cases were due to traumatic facial nerve palsy (39 of Head injuries causing fracture of the temporal bone and 48 of Iatrogenic facial palsy).

Table 1.

Total Number of cases of facial nerve decompression

| 1- Total number of cases of facial nerve decompression by trans mastoid approach—614 |

| A-Surgery for C S O M and Cholesteatoma—469 |

| B-Trauma—87 |

| a-Head injuries—39 |

| b-Iatrogenic facial palsy—48 |

| C-Bell’s palsy—58 |

I have also operated on 58 cases of facial nerve decompression due to Bell’s Palsy with slitting of the sheath through a transmastoid approach. All had thickened facial nerve sheath of varying degrees and oedema, 49 cases had congestion of nerve. One case had erosion of fallopian canal, 9 had formation of single or multiple fibrous bands (multiple bands in 7 cases and single near the stylomastoid foramen in 2 cases). A histopathology study of the facial nerve sheath was done in 8 cases and in such cases showed fibrosis, endarteritis with periarteritis and obliterative endarteritis. I have also tried to study facial nerve sheath during cadaveric temporal bone dissections in a few cases but it was very thin and I could not take an adequate size biopsy for histopathology (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraoperative findings in Bell’s palsy

| A- Thickened facial nerve sheath—58 |

| B- Oedema of the facial nerve—58 |

| C- Congestion of the facial nerve of varing degree—49 |

| D- Fibtrous bands in Mastoid/Second Genu of the facial nerve—9 |

| 1-Multiple—7 |

| 2-Single-near the Stylomastoid foramen—2 |

| 3-Erosion of fallopian canal—1 |

| E- Histopathology of facial nerve sheath—8 |

| Fibrosis with periarteirits, endarteritis &/or obliterative endarteirtis—8 |

Discussion

It is well known fact that Bell’s palsy is a controversial topic because of the various theories causing it and because of the role of surgical treatment. In my opinion all the theories discussed may play a part in the causation of a palsy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Flow chart—Aetiology of Bell’s palsy

| 1- Anatomical variations of fallopian canal |

| 2- Cold/viral prodrome |

| 3- Primary ischemia |

| Vasospasm—oedema and congestion of facial nerve |

| Reversible with Medical treament |

| 4- Secondary ischemia |

| Transudate formation and leads to zonal Ischemia |

| Reversible with medical treatment otherwise in addition may require facial nerve decompression by trans mastoid approach |

| 5- Tertiary ischemia |

| Thickening of facial nerve sheath with formation of fibrous band/bands |

| Can lead to Residual facial palsy |

| Facial nerve decompression with transmastoid approach and slitting of it’s sheath and cutting of fibrous band/bands is required along the medical treatment |

To summaries, in presence of anatomical variations of the fallopian canal, and particularly when the canal is dehiscent and the nerve is exposed, vasospasm of the stylomastoid artery which supplies the mastoid segment of facial nerve may occur. This leads to primary ischemia and manifests as edema and congestion of mastoid segment of facial nerve, but is reversible with timely treatment at this stage. At this stage there is pain of varying degree around the ear because of vasospasm. There may be associated viral prodrome which aggravates the condition. If due to any reason it progresses, then secondary ischemia may follow with formation of a transudate in the fallopian canal and around facial nerve leading to worsening of the palsy. In turn this secondary ischemia may progress to tertiary Ischemia.

It is this vasospasm, will progresses to periarteritis and obliterative endarteritis, that leads to fibrosis of varying degrees in the facial nerve sheath and, in turn, to thickening and strangulation of the nerve. There may be single or multiple fibrous band formation leading to further compression of nerve. This is the cause of long term facial palsy unless treated surgically by facial nerve decompression by trans mastoid route with slitting of the sheath and cutting of fibrous band/bands, thus relieving the compressing effects on the facial nerve and promoting it’s recovery. Medical treatment and physiotherapy also is important in treating it but physiotherapy has been always undisputable.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the Deans of T N Medical college and staff of E N T department during my tenure for helping me do this work. Dr N. K. Bhel Former Prof, Deparment of Pathology for help in preparing this paper. I am grateful to Professor Guy Kenyon (U.K) for his valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

D. S. Grewal is the Former Professor and Head, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, and Head and Neck Surgery at T N Medical College and B Y L Nair Charitable Hospital, Mumbai, India.

References

- 1.Drachmann D. Bell’s palsy-a neurological point of view. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;89:147. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1969.00770020149027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DonathT Lengyel. I The vascular structure of intratemporal section of the facial nerve, with special reference to peripheral facial palsy. Acta Med Acad Sci Hung. 1957;102:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calcaterra TC, Rand RW, Bentson JR. Ischemic paralysis of facial nerve: a positive etiological factor in Bell’s pasy. Larygoscope. 1976;86:92–97. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197601000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilger JA. The nature of Bell’s palsy. Larygoscope. 1949;59:228–235. doi: 10.1288/00005537-194903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunderland S. Blood supply of the peripheral nerves. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1945;54:280–282. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1945.02300100054005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grewal DS, Hathiram BT, Walvekar R, et al. Surgical decompression in Bell’s palsy—Our view point. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;54:198–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02993103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grewal DS (2012) Atlas of surgery of the facial nerve, 2nd edn. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. 2012 Bell’s palsy, pp 30–45

- 8.May M, Hardin WB. Facial palsy: interpretation of neurological findings. Am Acad Opthalmol Otol. 1977;84:710–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomita H. Facial nerve surgery. By Hogo Fish. Amesterdam: Kugler Medical Publication; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Naakaashiro Y, et al. Bell’s palsy and Hepes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneural fluid and muscle. Ann Int Med. 1996;124:27–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_Part_1-199601010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kettle K. Pathology and surgery of Bell’s palsy. Laryngoscope. 1963;73:837. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sade J, Levy E, Chaco J. Surgery and pathology of Bell’s palsy. Arch Otolarygol. 1965;82:594. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1965.00760010596007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grewal DS, Hathiram BT, Saraiya SV. Canal wall down Tympanomastoidectomy,” on disease “approach for retraction pockets and Cholesteatoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:832–839. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107006123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakar PK, Sawhney KL, Saharia PS. Familial Bells palsy (Case report) J Laryngol Otol. 1996;80:628–630. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100065750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firsh U. Surgery for Bell’s palsy. Arch Otolarngol. 1981;107:1–11. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790370003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proctor B. The anatomy of the facial nerve. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1991;24:479–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]