Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is a major global health threat. High prevalences of colonization and infection with multi-drug resistance organisms (MDROs) have been reported in patients undergoing dialysis. It is unknown if this finding extends to patients with mild and moderate/severe kidney disease. An observational study included all adult incident patients hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of infection in four hospitals from Guangzhou, China. Inclusion criteria: Serum creatinine measurement at admission together with microbial culture confirmed infections. Exclusion criterion: Undergoing renal replacement therapy. Four categories of Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were compared: eGFR ≥ 105, 60–104 (reference), 30–59, and <30 ml/min/1.73 m2. The odds ratio of MDROs, defined as specific pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp.) resistant to three or more antibiotic classes, were calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model across eGFR strata. Of 94,445 total microbial culture records, 7,288 first positive cultures matched to infection diagnosis were selected. Among them, 5,028 (68.9%) were potential MDROs. The odds of infections by MDROs was 19% and 41% higher in those with eGFR between 30–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Adjusted odds ratio, AOR): 1.19, 95% CI:1.02–1.38, P = 0.022) and eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (AOR: 1.41, 95% CI:1.12–1.78, P = 0.004), respectively. Patients with impaired renal function have a higher risk of infections by MDROs. Kidney dysfunction at admission may be an indicator for need of closer attention to microbial culture results requiring subsequent change of antibiotics.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is a major growing global threat because even common infections and minor injuries may becoming life threatening due to the increasing incidence of infections caused by multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs)1. As recently stated by the United Nations (UN) and World Health Organization (WHO), ABR has escalated into a global crisis that must be prioritized2,3.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) as well is a global health problem, affecting 10–15% of the population worldwide4,5. Patients with CKD are not only the victims of infection, but plausibly also a reservoir of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. An increased risk of infection has been reported in individuals with CKD, especially in those undergoing dialysis6. Higher rates of infection in patients with CKD result in more frequent use of antibiotics7 and more frequent hospitalization6,8,9, thereby increasing their exposure to microbes, including MDROs10.

High prevalences of colonization by, and infection due to MDROs, such as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), have been reported in patients undergoing dialysis11–14. However, it is currently unknown if non-dialysis CKD patients are at higher risk of infections caused by MDROs. Studying these infections is relevant given the potential nephrotoxicity of second and third line antibiotics15. What is worse, these patients can potentially transmit MDROs to patients in other sections of the healthcare facilities.

Since the recognition of CKD remains low4, pre-admission baseline kidney function, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), is not always available when patients are admitted to hospital. In clinical practice, eGFR at the time of admission represents an important indicator of kidney function that may help to inform clinical decision making, even though reduced eGFR at admission may represent acute and/or chronic kidney dysfunction.

The aim of this study was to explore the association between kidney function at admission and the risk of infections by MDROs in patients hospitalized with infections. Secondly, we tried to identify specific microbial patterns of infection among them. The existence of such patterns would help to inform public planning strategies to cope with antibiotic resistance.

Results

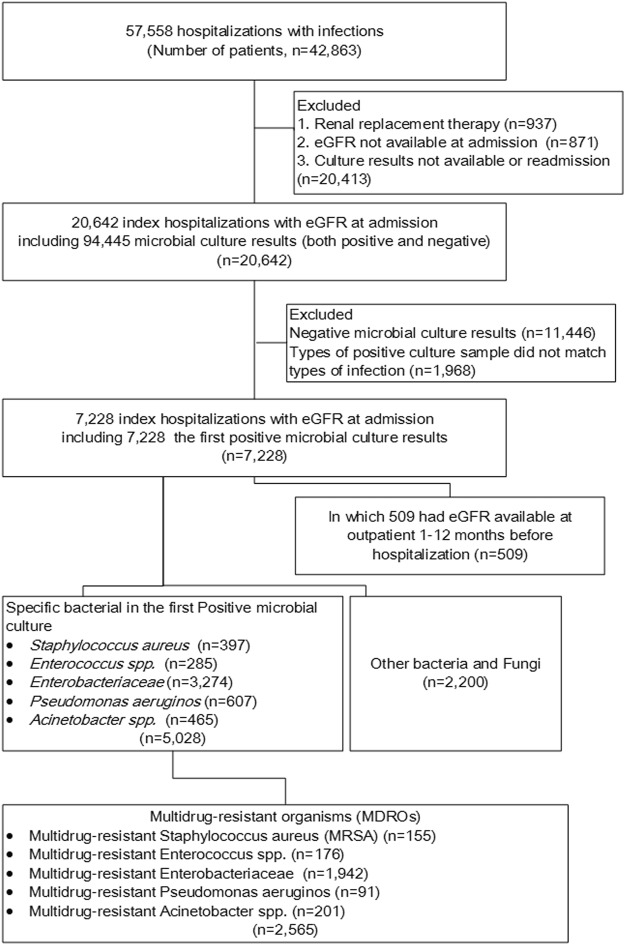

The flowchart of included microbial cultures

In total, 42,863 patients had 57,558 hospitalizations with infections during the study period. In their first hospitalization, 20,642 patients had 94,445 microbial culture results (both positive and negative). After excluding those without positive microbial results or infection diagnoses that were not matched to a culture confirmed sample, a total of 7,228 incident hospitalized patients with the first positive microbial culture results were included. Of these, 509 patients had eGFR available at a prior outpatient visit 1–12 months before hospitalization. Those samples with positivity for Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. accounted for 68.9% (5,028/7,228) of the first positive cultures. Among them, 51.0% (2,565/5,028) were MDROs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart.

Baseline demographics of patients in different groups

Of included patients (n = 5,028), 58.6% were females and the mean age was 70 years. The majority (n = 3,038, 60.4%) had normal or near-normal kidney function (eGFR of 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2). The most common comorbidities were cerebrovascular disease (35.0%), diabetes mellitus (30.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (18.6%), and cancer (17.9%). Undefined infection-related hospitalizations (IRHs) were the most common IRHs (64.0%), followed by community-acquired (26.0%) and healthcare-associated IRHs (10.0%). The prevalence of comorbidities was higher in lower eGFR categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of patients with first culture positive bacteria** stratified by eGFR categories.

| eGFR at admission | eGFR at admission (ml/min/1.73 m2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ≥105 | 60–104 | 30–59 | <30 | *P value | |

| (n = 5,028) | (n = 689) | (n = 3,038) | (n = 968) | (n = 333) | ||

| Age (years, median) [interquartile range] | 70 [58–79] | 46 [36–56] | 71 [60–79] | 78 [70–83] | 76 [65–81] | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 2,948 (58.6) | 393 (57.0) | 1,772 (58.3) | 564 (58.3) | 219 (65.8) | 0.05 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1 [0–2] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [1–2] | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | <0.001 |

| Single Comorbidities | <0.001 | |||||

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 90 (1.8) | 4 (0.6) | 42 (1.4) | 32 (3.3) | 12 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 344 (6.8) | 8 (1.2) | 150 (4.9) | 128 (13.2) | 58 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 57 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) | 26 (0.9) | 21 (2.2) | 8 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Cerebral vascular disease, n (%) | 1,783 (35.0) | 128 (18.6) | 1,082 (35.6) | 449 (46.4) | 124 (37.2) | <0.001 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 61 (1.2) | 4 (0.6) | 44 (1.5) | 9 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | 0.2 |

| Chronic obstructed pulmonary disease, n (%) | 933 (18.6) | 88 (12.8) | 606 (20.0) | 190 (19.6) | 49 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Connective tissue disease, n (%) | 105 (2.1) | 21 (3.1) | 59 (1.9) | 19 (2.0) | 6 (1.8) | 0.34 |

| Peptic ulcer, n (%) | 158 (3.0) | 14 (2.0) | 88 (2.9) | 38 (3.9) | 18 (5.4) | 0.01 |

| Paraplegia, n (%) | 10 (0.2) | 7 (1.0) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1,523 (30.3) | 107 (15.5) | 892 (29.4) | 371 (38.3) | 152 (46.0) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 900 (17.9) | 170 (24.7) | 558 (18.4) | 144 (14.9) | 28 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Severe liver disease, n (%) | 49 (1.0) | 6 (0.9) | 33 (1.1) | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.6) | 0.76 |

| Types of infection-related hospitalizations | <0.001 | |||||

| Total, n (%) | 5,028 (100.0) | 689 (100.0) | 3,038 (100.0) | 968 (100.0) | 333 (100.0) | |

| Community-acquired IRHs, n (%) | 1,309 (26.0) | 216 (31.4) | 773 (25.4) | 242 (25.0) | 78 (23.4) | 0.006 |

| Hospital-acquired IRHs, n (%) | 504 (10.0) | 106 (15.4) | 295 (9.7) | 84 (8.7) | 19 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Undefined IRHs, n (%) | 3,215 (64.0) | 367 (53.3) | 1,970 (64.9) | 642 (66.3) | 236 (70.9) | <0.001 |

*Mann-Whitney U test or Analysis of variance or Chi-square test or rank-sum test.

**Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginos, Acinetobacter spp.

Data from four hospitals of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China.

Culture positive rates

In the first hospitalization, 20,642 patients had 94,445 microbial culture results with eGFR available at admission. The culture-positive rate was 21.8%, 20.8%, 30.3%, 10%, 25% in overall, sputum, midstream, venous blood and other types of specimen, respectively. A higher overall culture-positive rate was observed as eGFR declined (P = 0.06). When categorized according to specific sample source, the same pattern remained only in the sputum (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences observed for culture positive rates in midstream urine (P = 0.6), venous blood (P = 0.7) or other specimen types (P = 0.7) (Supplementary Table 3).

Infection and microbial pattern in the first positive culture

Respiratory tract, genitourinary and bloodstream infections were the leading infections in these patients. (Supplementary Fig. 1) In 7,228 first positive microbial cultures, Gram-negative (G−) bacteria were the most commonly detected bacteria in the positive cultures, followed by Gram-positive (G+) bacteria, mycoplasmataceae and fungi. Compared to patients with eGFR 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2, the proportion of G− bacteria decreased (from 68% to 63%) across decreasing eGFR strata, while the proportion of G+ increased (from 14% to 18%). Among the G+ bacteria noted, Staphylococcus aureus (SA) was the most common among patients with eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, and Enterococcus spp. the most common one among patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2. Among the G− bacteria, Escherichia coli (E.coli) was the most common of all, followed by Klebsiella (Supplementary Fig. 2).

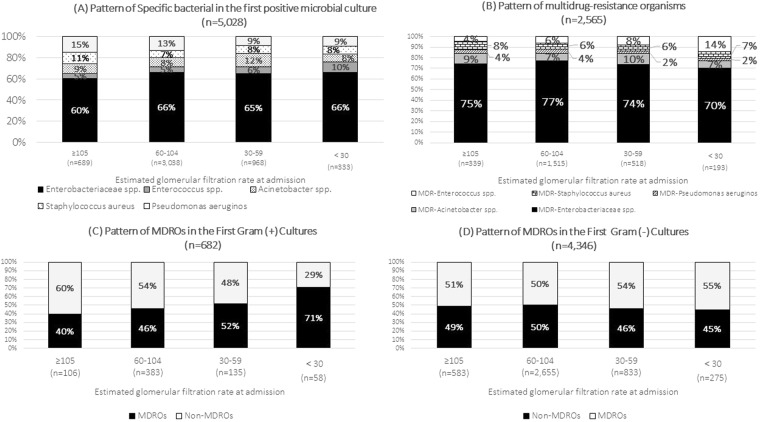

MDROs in the first positive culture

In 2,565 MDROs, a different pattern in the first positive culture was observed according to different eGFR categories. G+ MDROs increased while G− MDROs decreased from eGFR between 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2. Enterobacteriaceae spp. were the predominant MDROs, followed by Enterococcus spp., Acinetobacter spp., SA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Compared with eGFR between 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2, the proportion of Enterococcus spp. started to rise as the eGFR declined. (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The pattern of multidrug-resistance organisms in first positive microbial culture pattern by eGFR categories: (A) Pattern of Specific bacterial in the first positive microbial culture; (B) Pattern of multidrug-resistance organisms; (C) Pattern of MDROs in the First Gram (+) Cultures; (D) Pattern of MDROs in the First Gram (−) Cultures.

The crude MDRO proportions in the first positive cultures were 49.2%, 49.9%, 53.5% and 58.0% in patients with eGFR ≥ 105, 60–104, 30–59 and <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Regarding specific pathogen subgroups, the crude multidrug-resistant ratio increased with decreasing eGFR for MRSA, Enterobacteriaceae spp., Enterococcus spp. and Acinetobacter spp., but decreased for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The same trend was observed in the stratified analyses by disease subgroups and specimen subgroups, but not in venous blood specimen subgroups (Table 2).

Table 2.

MDROs in the first positive culture result in different groups by eGFR at admission categories.

| The first culture positive was MDRO* | eGFR at admission (ml/min/1.73 m2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDRO/Total | ≥105 | 60–104 | 30–59 | <30 | P value* | P trend** | |

| Overall MDROs***, n (%) | 2,565/5,028 | 339 (49.2) | 1,515 (49.9) | 518 (53.5) | 193 (58.0) | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Pathogen | |||||||

| Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, n (%) | 155/397 | 27 (36.5) | 86 (38.2) | 29 (39.7) | 12 (52.0) | 0.56 | 0.31 |

| Multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, n (%) | 1,942/3,274 | 252 (60.6) | 1,172 (58.4) | 383 (60.8) | 135 (61.4) | 0.57 | 0.2 |

| Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, n (%) | 91/607 | 13 (12.8) | 62 (15.8) | 12 (14.5) | 4 (13.3) | 0.87 | 0.56 |

| Multidrug-resistant Enterococcus spp., n (%) | 176/285 | 15 (46.9) | 92 (58.2) | 41 (66.1) | 28 (84.9) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp., n (%) | 201/465 | 32 (49.2) | 103 (40.4) | 53 (44.2) | 13 (52.0) | 0.46 | 0.26 |

| Disease | |||||||

| Single pneumonia with sputum specimen, n (%) | 487/1,169 | 74 (41.8) | 291 (40.9) | 87 (41.0) | 35 (50.0) | 0.53 | 0.04 |

| Single UTIs with urine specimen, n (%) | 1,284/2,151 | 144 (63.2) | 759 (58.3) | 271 (60.6) | 110 (63.2) | 0.35 | 0.08 |

| All sepsis with positive microbial culture, n (%) | 482/893 | 70 (50.7) | 232 (52.1) | 120 (56.3) | 60 (61.9) | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Specimen | |||||||

| Sputum, n (%) | 630/1,678 | 87 (35.4) | 378 (36.3) | 127 (41.2) | 38 (45.8) | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Midstream urine, n (%) | 1,397/2,307 | 152 (62.8) | 831 (59.3) | 299 (62.0) | 115 (63.5) | 0.46 | 0.14 |

| Venous blood, n (%) | 96/201 | 12 (33.3) | 62 (54.6) | 16 (44.4) | 3 (30.0) | 0.08 | 0.05 |

*Chi2 test in all subgroups; **The nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups from group 60–104 to group <30.

**MDROs: multi-drug resistance organism; Only applied in the five types of bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginos, Acinetobacter spp.; Resistant to three or more antimicrobial classes;

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate. UTI: urinary tract infection.

Data from four hospitals of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China.

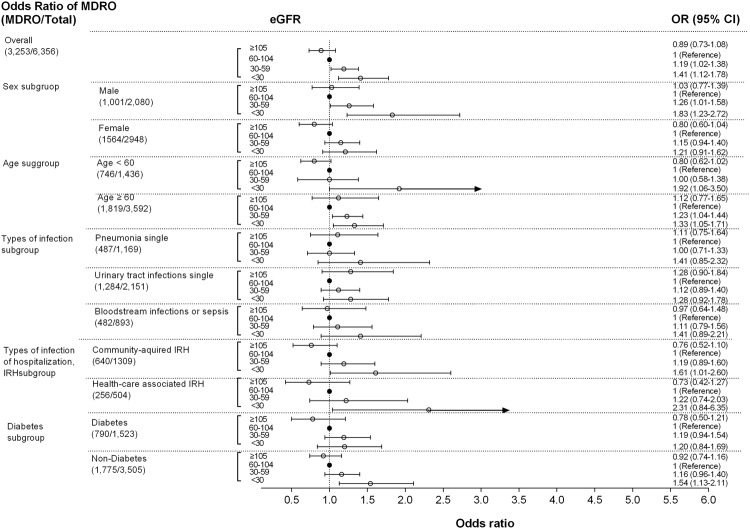

The results of multivariable logistic regression models showed increased odds of MDROs across lower eGFR strata. Compared to eGFR 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2, the odds of infections by MDROs were 19% and 41% higher in those with eGFR values between 30–60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Adjusted odds ratio, AOR): 1.19, 95% CI:1.02–1.38, P = 0.022) and eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (AOR: 1.41, 95% CI:1.12–1.78, P = 0.004), respectively.

In subgroup analysis, the trends persisted across sex, age strata, single pneumonia, single urinary tract infections, sepsis, community-acquired infection, health-care associated infection and in patients with or without diabetes, although they did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The odds ratio of MDROs in the first positive culture by different eGFR categories in Guangzhou, China. Sex subgroup adjusted by age and Charlson comorbidity index; Age subgroup adjusted by sex and Adjusted by Charlson comorbidity index; The rest of subgroups adjusted by age, sex and Charlson comorbidity index. *MDROs: multi-drug resistance organism; Defined by the following bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginos, Acinetobacter spp.; Resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes; IRH: infection-related hospitalization.

In those with eGFR values determined 1–12 months prior to hospitalization, a sensitivity analysis demonstrated consistently higher risk of MDROs in those with lower eGFR categories, although the results were not statistically significant in this relatively small group (Supplementary Fig. 3). The higher odds of MDROs in those with low eGFR values at admission were observed, regardless of whether or not reduced renal function existed at a prior outpatient visit (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

Our study shows that poorer kidney function at the time of hospital admission is associated with a higher probability of having MDROs. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association of kidney function at admission with infection by MDROs in adults without end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The finding in the current study of such an association is of potential clinical relevance. The main clinical application of this study lies in the need to consider the presence of renal dysfunction at admission as a signal to pay closer attention to the microbial culture results, given that identified pathogens may be potentially resistant to first-line initial antibiotics. Therefore, a subsequent modification of the initial antimicrobial therapy is needed if resistance to the current therapy exists. Our study also identifies patients with impaired renal function as a high-risk group for MDROs infections in need of close monitoring.

Previous studies have mainly focused on the higher risk of infection caused by MDROs, such as MRSA and VRE, in patients undergoing hemodialysis (1, 2)11–14. To our knowledge, there are no data to suggest whether or not the association may extend to milder levels of reduced renal function not requiring dialysis. Shorr et al. documented that long-term hemodialysis was an independent risk factor associated with infection due to antibiotic resistant bacteria16. An analysis from the CDC Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) system showed that the incidence of invasive MRSA infection in dialysis patients was 23.3 cases per 1000 persons, a rate that was 100 times greater than that in the general population14. Similar statistics have been reported from the United Kingdom (UK), where 4.2% of all episodes of MRSA bacteremia occurred among dialysis patients17. Our findings showed that higher odds of infection caused by MDROs were observed as the eGFR declined below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, and were even higher in the group eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 compared to the group with eGFR between 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Many factors might contribute to the higher odds of MDRO infections in patients with reduced renal function. Frequent exposure to antibiotics is the main driver of ABR1. Patients with reduced eGFR have a higher risk of antimicrobial exposure due to their susceptibility to infections6,8,9,18–20, either prescribed by physicians or self-prescribed. Infection susceptibility due to immune dysfunction has also been proposed in patients with impaired renal function, including increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), accumulation of toxic products, and functional abnormalities of monocytes, T lymphocytes and natural killer cells21,22. Furthermore, patients with more severely reduced renal function generally have more frequent contact with healthcare personnel and environments (e.g. hospitals), as well as other patients, due to comorbidities and complications6. This increases their potential exposure to MDROs. The high proportion of MDROs in our study is comparable to that of other studies in China (such as MDR Acinetobacter baumannii: 57.5–72.8%, MRSA: 44.6–73.5%)23,24. China is one of the leading antibiotic prescribing countries in the world and is facing the problem of misuse and overuse of antibiotics25–27. This might be the reason for the higher proportion of MDROs in the microbial results in our study than those in other western countries. The Chinese central government has started to address this problem with a more stringent antimicrobial stewardship policies since 2012, including restriction of antibiotic prescription to doctors, prevention of self-prescription, development of audit and inspection systems, and investigation and reassignment of responsibility to hospital management staff who violate rational use policies. These initiatives may take some time to mitigate the increased susceptibility of patients with reduced eGFR due to MDRO infection24,28. For physicians in clinical practice, close attention to eGFR at admission should inform clinical decision-making regarding rational prescription of initial and subsequent antibiotics in order to control the antibiotic resistance problem.

The strengths of this real-world study are its careful design and richness of information including microbial cultures from linked electronic medical databases. Although a high presence of MDROs has been documented in China, we were able to identify different odds or risks of MDROs across different eGFR strata even in the high MDRO context. Our findings are from Guangzhou, a city in the southern part of China, and may not be generalizable to other populations. However, we speculate that comparable associations may also be present in other populations with similar social status, income level and accessibility to antibiotics. The results should be interpreted considering the following limitations. (1) To define renal function, we used a single measurement of eGFR at admission, which may have resulted in misclassification of true eGFR as patients’ renal function may not have been in steady state at the time. Thus, it was not possible to determine with certainty whether patients with low eGFR values at hospital admission had acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease or a combination of the two. A sensitivity analysis examining the relationship between eGFR values determined 1–12 months prior to hospitalization and MDROs demonstrated consistent findings to those of the main analysis, although the results were not statistically significant, possibly due to the more limited sample size. (2) We only focused on the first positive culture as the outcome, which was influenced by culture positive rate, previous hospitalization, antibiotic use before admission or admission from a nursing home29–31. There was no significant difference in culture positive rates among patients with different eGFR categories in our sample (Supplementary Table 3). However, we did not have access to a regional registry that allowed us to identify previous hospitalization and antibiotic use. (3) A positive culture could be related to contamination or colonization, rather than indicating the causative pathogen of infection. The possibility of a false positive culture result was mitigated by specifically matching a symptomatic clinical diagnosis with relevant types of positive culture samples. Residual and unknown confounding may have influenced our estimates. (4) As this is an observational study, the observed association between impaired renal function and MDROs cannot be used to draw causal inferences.

Our study suggests that patients with CKD at admission have a higher likelihood of having MDRO infections. This information may increase the awareness among physicians about the prognostic value of creatinine tests at admission, and aid in the choice of initial antibiotics.

Methods

Study Design

This was an observational study using electronic health records.

Setting and data source

We used electronic healthcare data from four hospitals belonging to a healthcare conglomerate, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (GDHCM), China. GDHCM is located in Guangzhou city with a population of 13,080,500 residents as of 201532. GDHCM serves as one of the main referral centers for the area, with over 5 million outpatient visits and 70,000 inpatients per year. The four hospitals share the same electronic medical record database (EMRD), developed by International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), and which includes both inpatient and outpatient medical records.

Participants

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were adults (≥18 years), were hospitalized with at least one discharge diagnosis of infection according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), between August 2012 and December 2015 (see Supplementary Table 1 for definitions33), had a positive microbial culture result in which the type of sample matched the type of infection, and had at least one serum creatinine (sCr) measurement available at admission. Patients receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT, kidney transplantation or dialysis) were excluded. For patients with multiple hospital admissions, only the first admission record was used. The reasons why discharge diagnosis was used to confirm a hospitalization with infection included (1) need to capture all infections, including community acquired infection and health-care associated infection; (2) evidence was not always present to establish an infection diagnosis at admission. In the case of multiple infection diagnoses during the same hospitalization, only one infection-related diagnosis was used and only if the type of first positive culture aligned with the discharge diagnosis (Supplementary Table 2). For example, the first positive midstream urine culture should match to urinary tract infections; Bacteraemia/sepsis was valid if it had positive culture of any type and no other organ specific infection diagnosis. Thus, each hospitalization had a unique culture-confirmed infection diagnosis.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, China (B2016-194-01). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived. All patient data were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

Renal function estimation

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated from serum creatinine (sCr) concentration at admission (the first value was considered if more than one test was taken on the same day), using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula34. Patients were divided into four categories of eGFR: eGFR ≥ 105, 60–104, 30–59, and <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, with eGFR of 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2 serving as the reference group because this range showed the lowest risk of infection in a previous study and higher eGFR, for example eGFR ≥ 105 ml/min/1.73 m2 might indicate malnutrition, which would be predisposed to high risk of infection9.

Microbial susceptibility test and MDROs

Sampling and culture were performed according to standard procedures35. Microbiological tests based on Gram staining, microscopic observation of bacterial morphotypes, characteristics in culture medium and various specific biochemical reactions were applied to identify bacteria according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) procedures36. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was also performed according to CLSI procedures, and micro-organisms were tested using a susceptibility panel35. The antibiotics panel used for susceptibility testing was applied according to CLSI guidelines and local prescription pattern. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by susceptibility analysis system (MicroScan® WalkAway® 96 Plus; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The antibiotic susceptibility was interpreted using the CLSI MIC breakpoints at the time the test was conducted35. The standard and quality of the laboratory in GDHCM is certified by the International Organization for Standardization, ISO 15189.

MDROs were limited to a first culture positive pathogen of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Enterobacteriaceae (other than Salmonella and Shigella), Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp., and acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antibiotic classes, defined by European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)37. The first positive culture was used to avoid the influence of the initial antimicrobial therapy on culture result and different culture results during the same hospitalization.

Covariates

Patient age and sex were extracted from the medical records. According to the classification of Charlson comorbidities index using an established ICD-10 algorithm38, comorbid conditions were ascertained from the discharge diagnosis, including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease, diabetes without chronic complication, diabetes with chronic complication, hemiplegia or paraplegia, any malignancy, moderate or severe liver disease, metastatic solid tumor and AIDS/HIV. According to the GDHCM policy, discharge diagnosis was forced to include all the comorbid conditions from patients’ medical histories. Numbers of cultures, types of specimens and types of infection-related hospitalizations (IRHs) were extracted from the EMRD.

IRHs were sub-classified as health care-associated IRH (HAIRHs), community-acquired IRH (CAIRHs), and undefined IRH (UIRHs). HAIRHs were defined as the onset of infection after 48 hours following admission and confirmed by health care-associated infection report in the database which was audited by infection control healthcare professionals in GDHCM. CAIRHs were defined as those with infection diagnosis at admission. UIRHs were those that did not fulfill any of the criteria above.

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables were summarized using mean ± standard deviation, or median and interquartile range, as appropriate, while categorical variables were summarized using proportions. Differences in baseline characteristics and the proportion of MDROs in the first culture result between groups of patients within the 4 different eGFR categories were compared using ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square test, Fisher´s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. All the data extracted from EMRD in our study were complete, with no missing data and loss to follow-up.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of MDROs in the first culture result among different categories of eGFR. Covariates included age group (18–44; 45–59; 60–74; ≥75 years), sex, and Charlson comorbidity index (excluding the renal disease score). A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Additionally, we repeated the main analysis in subgroups: different sex, age groups, diabetes groups, cause-specific infection-related outcomes including blood stream infections or sepsis, pneumonia and urinary tract infections and types of hospitalization. In light of the fact that reduced eGFR values at admission may have represented pre-existing renal impairment, we performed a sensitivity analysis in those with and without pre-existing reduced renal function. Reduced renal function at admission without pre-existing renal impairment was defined as eGFR 60–104 ml/min/1.73 m2 at outpatient visit 1–12 months preceding hospitalization and eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at admission. Reduced renal function at admission with pre-existing reduced renal function was defined as eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 both at preceding outpatient visits and at admission. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to estimate the relative risk of MDROs in the first culture result across different eGFR strata using log binomial model. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Chuanliang Yi, Jiajie Huang, Haoyang Fu and the department of information for their help with the data extraction from GDHCM. We thank Qiang Zhou from the microbial culture room, the department of laboratory, for his support in the report of microbial culture result. This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the People’s Republic of China (No. 2013BAI02B04; No. 201407001-1 A; No. 201407005) and the grant from Guangzhou science and technology project (2016201604030085). This work was also supported by a research grant from a project between the Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, China and the Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, funding from Foreign Experts Project, Foreign Experts Bureau of Guangdong Province, China [GDT20164400034] and Science and technology research funding of Chinese medicine from Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (No. 2014KT1305, No. YN2018QL08, No. 2017KT1392). GBS acknowledges China government scholarship from China scholarship council (No. 201508440214). DJ acknowledges practitioner fellowship funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. JJC acknowledges funding from Stockholm County Council, Westman and Martin Rind Foundations and the Swedish Heart and Lung Association. Baxter Novum is the result of a grant from Baxter Healthcare Corporation to Karolinska Institutet. The funding source was not involved in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of Foreign Experts Project, Foreign Experts Bureau of Guangdong Province, China.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, data acquisition, or data analysis and interpretation. Specifically, G.B.S., Z.R.H., Z.H.W. and X.S.L. performed the data collection and extraction. G.B.S., J.J.C., B.L., D.J. and C.S.L. participated in the study design and clinical data monitoring or data interpretation. G.B.S., E.R., H.X., L.M.L. and G.M. performed the biostatistics analysis. G.B.S., J.J.C., B.L. and C.S.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved either in the drafting or the revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of Guangdong provincial hospital of Chinese medicine.

Competing Interests

Bengt Lindholm is employed by Baxter Healthcare Corporation. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31612-1.

References

- 1.Holmes AH, et al. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet. 2016;387:176–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinl J. UN declaration on antimicrobial resistance lacks targets. Lancet. 2016;388:1365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31769-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization, W. H. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/global-action-plan/en/ (2015).

- 4.Levin A, et al. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. Lancet. 2017;390:1888–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bello AK, et al. Assessment of Global Kidney Health Care Status. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2017;317:1864–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald HI, Thomas SL, Nitsch D. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for acute community-acquired infections in high-income countries: a systematic review. Bmj Open. 2014;4:e4100. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Lancet Infectious, D Antibiotic resistance: long-term solutions require action now. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:995. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald HI, Thomas SL, Millett ERC, Nitsch D. CKD and the Risk of Acute, Community-Acquired Infections Among Older People With Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Cohort Study Using Electronic Health Records. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:60–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James MT, et al. CKD and Risk of Hospitalization and Death With Pneumonia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:24–32. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calfee DP. Multidrug-Resistant Organisms Within the Dialysis Population: A Potentially Preventable Perfect Storm. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:3–5. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Ziakas PD, Rice LB, Mylonakis E. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Colonization Among Dialysis Patients: A Meta-analysis of Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Significance. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:88–97. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Meta-Analysis of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Colonization and Risk of Infection in Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2131–2141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013091028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowley L, Wilson J, Guy R, Pitcher D, Fluck R. UK Renal Registry 14th Annual Report: Chapter 12 Epidemiology of Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteraemia Amongst Patients Receiving Dialysis for Established Renal Failure in England in 2009 to 2011: A Joint Report from the Health Protection Agency and the UK Renal Registry. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:C233–C245. doi: 10.1159/000342856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Report Emerging Infections Program Network Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/mrsa14.pdf (2014).

- 15.Rocco, M. et al. Risk factors for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients receiving high intravenous doses of colistin methanesulfonate and/or other nephrotoxic antibiotics: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care17, 10.1186/cc12853 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. Prediction of Infection Due to Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria by Select Risk Factors for Health Care-Associated Pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2205–2210. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fluck R, Wilson J, Tomson CRV. UK Renal Registry 12th Annual Report (December 2009): Chapter 12 Epidemiology of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteraemia Amongst Patients Receiving Dialysis for Established Renal Failure in England in 2008: a joint report from the UK Renal Registry and the Health Protection Agency. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115:C261–C270. doi: 10.1159/000301235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang ST, et al. Pneumococcal pneumonia infection is associated with end-stage renal disease in adult hospitalized patients. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James MT, Laupland KB. Examining Noncardiovascular Morbidity in CKD: Estimated GFR and the Risk of Infection. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:327–329. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalrymple LS, et al. The Risk of Infection-Related Hospitalization With Decreased Kidney Function. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:356–363. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betjes MG. Immune cell dysfunction and inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato S, et al. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephro. 2008;3:1526–1533. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00950208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, Q., Xu, Y. C., Kiratisin, P. & Dowzicky, M. J. Antimicrobial activity among gram-positive and gram-negative organisms collected from the Asia-Pacific region as part of the Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial: Comparison of 2015 results with previous years. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.08.014 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Xiao YH, Li LJ. China’s national plan to combat antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16:1216–1218. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paterson DL, van Duin D. China’s antibiotic resistance problems. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017;17:351–352. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao YH, Li LJ. Legislation of clinical antibiotic use in China. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13:189–191. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heddini A, Cars O, Qiang S, Tomson G. Antibiotic resistance in China-a major future challenge. Lancet. 2009;373:30–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61956-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao, Y. H. et al. Changes in Chinese Policies to Promote the Rational Use of Antibiotics. Plos Med10, 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001556 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Bell, B. G., Schellevis, F., Stobberingh, E., Goossens, H. & Pringle, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. Bmc Infect Dis14, 10.1186/1471-2334-14-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Goossens H, Ferech M, Stichele RV, Elseviers M, Grp EP. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365:579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross AE, et al. Epidemiology and Predictors of Multidrug-Resistant Community-Acquired and Health Care-Associated Pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 2014;58:5262–5268. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02582-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics, G. Guangzhou population, http://www.gzstats.gov.cn/tjyw/201604/t20160412_39495.htm (2015).

- 33.Dalrymple LS, et al. Outcomes of Infection-Related Hospitalization in Medicare Beneficiaries Receiving In-Center Hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:754–762. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levey AS, et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 24th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S24. (Wayne, PA, 2014).

- 36.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. In Document M35-A2, 2nd ed.Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2015).

- 37.Magiorakos AP, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quan HD, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of Guangdong provincial hospital of Chinese medicine.