Abstract

Introduction

Staphylococcal infection–related glomerulonephritis (GN) has been shown to represent a unique form of infection-related GN that contains IgA-dominant deposits and is often seen concurrently with the bacterial infection. Biopsies commonly reveal an endocapillary proliferative and/or exudative or mesangial proliferative GN. Rare cases have been reported to show cryoglobulin-like features, including hyaline pseudothrombi and wireloop deposits; however, detailed characterization of these cases is lacking.

Methods

The pathology archives from the University of Utah and Sharp Memorial Hospital were reviewed from January 2016 to September 2017 in search of cases with GN containing IgA-dominant deposits and features of cryoglobulinemia.

Results

Of 1965 native kidney biopsies, 5 showed IgA-dominant GN with cryoglobulinemic features. All patients had active staphylococcal infections at the time of biopsy. All presented with acute kidney injury (serum creatinine range: 1.7−6 mg/dl), and all had proteinuria and hematuria. All biopsies showed exudative GN, and 4 biopsies had focal crescents. All had focally prominent hyaline pseudothrombi with or without wireloop deposits, and all showed co-dominant staining for IgA and C3 on immunofluorescence microscopy. Serologic testing for cryoglobulinemia was performed in 3 patients and was transiently positive in 1 patient. Four patients required hemodialysis at last follow-up, whereas 1 patient returned to baseline kidney function.

Conclusion

IgA-dominant GN with cryoglobulinemic features is an uncommon but severe form of glomerular injury in patients with staphylococcal infections. Four of 5 patients had crescentic glomerular injuries, all of whom required hemodialysis at last follow-up. Patients with IgA-dominant GN with features of cryoglobulinemia should be evaluated for active staphylococcal infection.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, cryoglobulinemia, infection-related glomerulonephritis

GN related to bacterial infection has long been recognized as a form of kidney injury, with early descriptions of post-streptococcal GN dating back to the 19th century.1 Although post-streptococcal disease has represented the prototypical example of bacterial infection-related GN, the past 2 decades have seen an epidemiological shift in the underlying cause, morphologic features, and therapeutic regimens for this collection of diseases.2 In developed countries, staphylococcal species have emerged as common etiologic agents in cases of bacterial infection-related GN (IRGN) and are associated with distinct morphologic features and clinical implications that differ from classic postinfectious GN. GN associated with staphylococcal infection shows deposits that stain in a dominant or co-dominant fashion for IgA and the C3 component of complement by immunofluorescence microscopy and clinically occurs in the setting of an active infection.

During the last decade, an increasing body of literature has been amassed regarding the morphologic and clinical features of staphylococcal IRGN. Although diffuse proliferative and exudative GN is the most commonly encountered pattern of glomerular injury, less common injuries including GN with cryoglobulinemic features have been rarely reported.3, 4 We present a clinicopathologic series of 5 patients with cryoglobulin-like GN with IgA-dominant deposits, all of whom had an active Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) infection at the time of biopsy.

Materials and Methods

The pathology archives from the University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT) and Sharp Memorial Hospital (San Diego, CA) were searched from January 2016 to September 2017. All cases were processed for standard light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. Cases that showed GN with IgA-dominant deposits were reviewed for descriptions of cryoglobulinemic features, such as hyaline pseudothrombi and wireloop deposits. Hyaline pseudothrombi were defined as intracapillary plugs within glomeruli that were eosinophilic on hematoxylin and eosin stain and stained strongly on periodic acid Schiff, with pale to negative staining on the Jones methenamine silver stain. Other features included a homogenous appearance of the intracapillary plug and a cleft between the intraluminal material and capillary basement membrane. Wireloop deposits were defined as segmental band-like hyaline thickening of capillary loops with a staining pattern similar to that described for hyaline pseudothrombi. After identification of cases of IgA-dominant GN with cryoglobulinemic features, pathologic and clinical data were reviewed, as was clinical follow-up, when available.

Reviewed clinical features included presence of an underlying infection, serologic studies (including cryoglobulin studies, viral and/or autoimmune serologic studies, and presence of a paraprotein), presence of proteinuria and/or hematuria, and renal function. Nephrotic-range proteinuria was defined as 3.5 g of protein per day or a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 3.5 g/g.

Results

Biopsy Selection

During the study period, 1965 native kidney biopsies were reviewed, 258 (13%) of which showed immune complex deposition with IgA-dominant staining by immunofluorescence microscopy. Of the biopsies with IgA-dominant deposits, 5 showed hyaline pseudothrombi with or without wireloop deposits on light microscopy. These 5 biopsies represented 0.25% of all native kidney biopsies during the study period and 1.9% of biopsies with IgA-dominant deposits.

Clinical Features at Presentation

All 5 patients with IgA-dominant deposits and cryoglobulinemic features had active bacterial infections with S aureus at the time of biopsy. Clinical characteristics of these patients are detailed in Table 1. Three patients were men, and 4 were older than 60 years of age. All 5 patients presented with acute kidney injury (serum creatinine range: 1.7−6 mg/dl), 1 of whom was anuric (patient #3). Proteinuria and hematuria was present in all 4 patients making urine. Degree of proteinuria was quantified in 2 patients and was in the nephrotic range in 1 patient (patient #2). Three patients required hemodialysis at presentation (patients #1, 3, and 5). Patient #5 had underlying diabetes mellitus, and patient #4 had a history of rheumatoid arthritis being treated with methotrexate. Two patients (patients #3 and 5) had leg ulcers as the primary site of infection. Two patients had deep seated infections, including 1 patient with vertebral osteomyelitis (patient #2) and 1 patient with an epidural abscess adjacent to the lumbar spine (patient #4). Patient #1 presented with bullous impetigo. Three patients (patients #2, 4, and 5) had bacteremia. Bacterial cultures were available for 4 patients, all of which grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA). The patient with bullous impetigo was presumed to have a S aureus infection. Serologic testing for cryoglobulins was performed in 3 patients and was initially positive in patient #3 with cryoprecipitate composed of IgA (4 mg/dl; reference: 0 mg/dl), IgG (4 mg/dl; reference: 0 mg/dl), and IgM (5 mg/dl; reference: 0 mg/dl). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) with immunofixation electrophoresis concurrent with the positive cryoglobulin assay was suggestive of monotypic IgA-λ; however, repeat testing upon hospital transfer was negative for both cryoglobulins and paraprotein. SPEP was performed on 3 additional patients (patients #2, 4, and 5), all of whom showed a polyclonal increase in IgA without monoclonal proteins. Complement C3 levels were low to borderline low in all 4 patients with available results (range: 41−85 mg/dl; reference range: 88−201 mg/dl), and C4 levels were normal in all tested patients. Four patients had testing performed for hepatitis C virus (HCV), and 1 patient (patient #2) had positive antibodies with elevated viral RNA of 3,000,000 IU/ml. Two patients underwent testing for rheumatoid factor, which was negative in both.

Table 1.

Clinical features

| Patient | Age (yr)/sex | Infection | Cryoglobulin | HCV | C3 (mg/dl) | Presenting SCr (mg/dl) | Treatment | Follow-up time (mo) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 33/F | Bullous impetigo | Negative | Negative | N/A | 3.7 | Antibiotic + CS | 1 | HD |

| #2 | 62/M | MSSA/osteomyelitis, bacteremia | Negative | Positive | 83 | 4.3 | Antibiotic + CS | 3 | HD |

| #3 | 75/M | MSSA/foot ulcer | Positive | Negative | 41 | 4 | Antibiotic | 9 | HD |

| #4 | 63/F | MSSA/epidural abscess, bacteremia | N/A | Negative | 60 | 1.7 | Antibiotic | 2 | SCr: 0.75 mg/dl |

| #5 | 61/M | MSSA/diabetic foot, bacteremia | N/A | N/A | 85 | 6 | Antibiotic | 6 | HD/Expired |

CS, corticosteroids; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HD, hemodialysis; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; SCr, serum creatinine.

Kidney Biopsy Findings

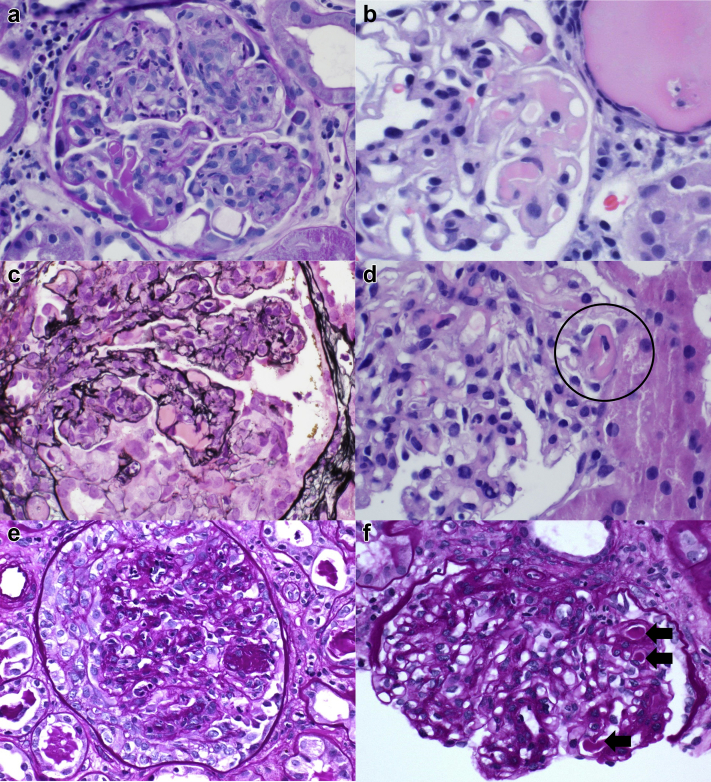

The pathologic features are summarized in Table 2. Light microscopic evaluation revealed a mean of 25 glomeruli (range: 13−34). All biopsies showed proliferative and exudative GN, which was diffuse in 4 patients and focal in 1 patient (patient #4). One biopsy (patient #2) showed focal membranoproliferative changes, including glomerular basement membrane duplication. The biopsy for patient #5 showed a background of moderately advanced diabetic glomerulosclerosis with focal nodular mesangial expansion. All biopsies showed focally prominent immune complex deposition in the form of hyaline pseudothrombi with or without wireloop deposits (Figure 1a−f). Hyaline pseudothrombi and/or wireloop lesions involved a mean 22% of sampled glomeruli (range: 6%−58%). Of note, cryoglobulinemic features were not identified in any biopsies with noninfectious IgA-dominant GN during the study period. Focal crescent formation was identified in 4 biopsies, involving 23% to 46% of the sampled glomeruli, and glomerular fibrinoid necrosis was focally present in 3 biopsies, involving 6% to 29% of sampled glomeruli. In comparison, 26 cases of IgA-dominant IRGN without cryoglobulinemic features were identified at the University of Utah and Sharp Memorial Hospital during the study period, and crescents were present in 10 (38%) biopsies. The degree of global glomerular sclerosis was focal in all 5 cases (range: 5%−40%). All cases showed at least focal interstitial inflammation, and the degree of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy was moderate in 1 case (patient #5) and minimal (<10%) in the remaining 4 cases. One biopsy (patient #5) showed moderate arterial and arteriolar sclerosis, whereas the other 4 showed no more than mild chronic vascular disease.

Table 2.

Pathologic features

| Patient | LM injury | Crescents/FN (%) | Global sclerosis (%) | HT/WL (%) | IF/TA | IF | EM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | DPGN | 23/0 | 8 | 58 | Minimal | 3+ IgA/C3, 2+ IgG/κ/λ, tr IgM | SEN, SEP, IM, Mes |

| #2 | DPGN/MPGN | 23/13 | 6 | 17 | Minimal | 3+ IgA/C3, 3+ κ, 1+ IgG/IgM/λ | SEN, Mes |

| #3 | DPGN | 46/6 | 29 | 20 | Minimal | 3+ C3, 2+ IgA/κ/λ, tr IgG/IgM | SEN, Mes, IL |

| #4 | FPGN | 0/0 | 5 | 8 | Minimal | 3+ C3, 2+IgA, 1+ κ, tr IgM/λ | SEN, Mes |

| #5 | DPGN | 45/29 | 40 | 6 | Moderate | 3+ IgA/C3, 2+ κ, 1+IgM/λ | SEN, Mes, SEP |

DPGN, diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis; EM, electron microscopy; FN, fibrinoid necrosis; FPGN, focal proliferative glomerulonephritis; HT, hyaline pseudothrombi; IF, immunofluorescence; IF/TA, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy; IL, intraluminal; IM, intramembranous; LM, light microscopy; Mes, mesangial; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; SEN, subendothelial; SEP, subepithelial; tr, trace (<1+); WL, wire-loop deposits.

Minimal: <10% fibrosis and atrophy; moderate: 25% to 50% fibrosis and atrophy.

Figure 1.

By light microscopy, all cases showed proliferative and exudative glomerulonephritis with focal features suggestive of cryoglobulinemia, including hyaline pseudothrombi. Patient #1 (a), patient #2 (b), patient #3 (c), and patient #5 (f) (arrows) and wireloop deposits (patient #4 [d]; circle). Cellular crescents (patient #3 [c], patient #5 [e]) were identified in 4 of 5 cases.

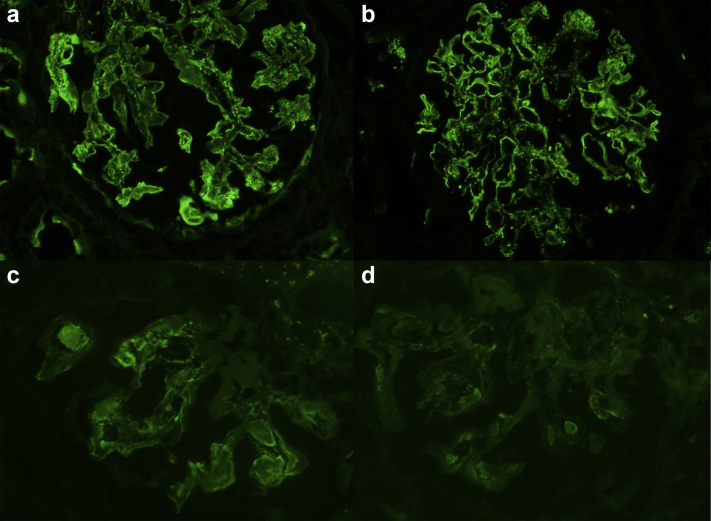

By immunofluorescence microscopy, all biopsies showed co-dominant staining of glomerular deposits for IgA and C3 (Figure 2a-d). Judged on a scale of 0 to 3+, 3 biopsies showed 3+ diffuse coarse granular capillary wall and mesangial staining for IgA, whereas 2 biopsies showed 2+ staining. All 5 biopsies demonstrated 3+ staining for C3 in a similar distribution. Mesangial and segmental capillary wall staining for IgM was present in lesser levels in all biopsies (trace: 1+), and similar staining for IgG was identified in 3 biopsies (trace: 2+). Deposits in all cases were polytypic, with staining for both κ and λ light chains. Staining for C1q was absent in all cases. There was no staining of tubular basement membranes, interstitial areas, or vessels in any case.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy showed dominant or co-dominant staining in all cases for IgA (a) and C3 (b) (patient #2), including in hyaline pseudothrombi (IgA [c] and C3 [d]) (patient #1).

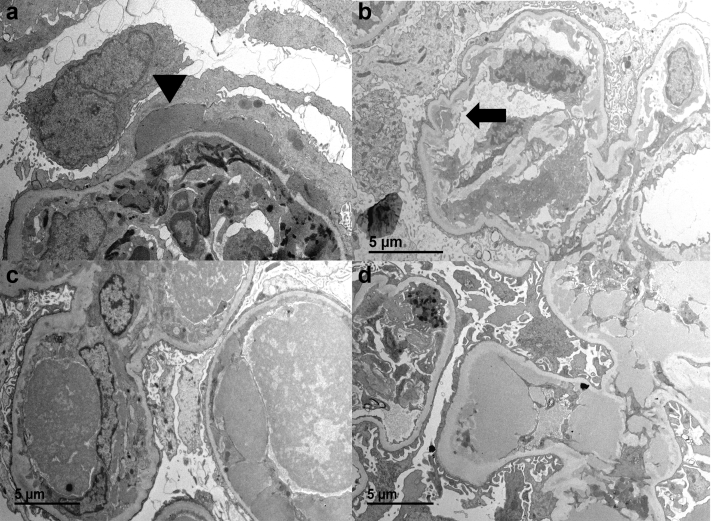

Ultrastructural examination revealed immune-type electron dense deposits in all cases (Figure 3a−d). All 5 biopsies demonstrated subendothelial and mesangial deposits, whereas 2 cases (patients #1 and 5) showed subepithelial deposits, which were hump-like in 1 case (patient #1). The biopsy for patient #1 also had segmental small intramembranous deposits that were oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane. One case (patient #3) had prominent intraluminal deposits in the sample with a variegated appearance; however, definitive substructural organization was not seen in any of the cases. Endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions were absent in examined areas in all cases.

Figure 3.

By electron microscopy, all patients had subendothelial and mesangial immune-type electron-dense deposits. One patient (patient #1) had subepithelial hump-like deposits (a) (arrowhead) and 1 patient (patient #2) had abundant subendothelial deposits with segmental duplication of the glomerular basement membrane (b; arrow). One patient (patient #3) had prominent intraluminal deposits on the sample for electron microscopy (c), and one (patient #4) demonstrated large subendothelial deposits corresponding to wireloop deposits on light microscopy (d).

Treatment and Clinical Follow-up

After biopsy, all 5 patients were treated with antibiotic therapy, and 2 patients also received corticosteroids. Clinical follow-up was available for a mean of 4.2 months (range: 1−9 months). At last follow-up, 4 patients (all of whom had diffuse proliferative GN with crescents) required hemodialysis at 1, 3, 9, and 6 months, respectively (patients #1, 2, 3, and 5). Patient #5 died approximately 6 months after presentation while still requiring hemodialysis. Patient #4 had a complicated hospital course, with hypoxic respiratory failure and encephalopathy. She was treated with antibiotics and at last follow-up had returned to baseline serum creatinine.

Comparison to IgA-Dominant IRGN Without Cryoglobulinemic Features

To further evaluate the clinical and pathologic characteristics of the described patients with IgA-dominant IRGN with cryoglobulinemic features, similar cases without wireloop deposits or hyaline pseudothrombi were pulled for comparison. Eight patients without cryoglobulinemic features who had clinical follow-up data available were included. All 8 patients presented with kidney injury with acutely elevated serum creatinine ranging from 1.6 to 8.5 mg/dl. All had hematuria and proteinuria, including 3 in the nephrotic range. Five (63%) had underlying diabetes mellitus, and all had an identified site of infection, including foot wounds and/or ulcers (n = 4), infected hardware (n = 2), osteomyelitis (n = 1), and joint infection (n = 1). S aureus was isolated in 4 patients.

On biopsy, 7 (88%) showed diffuse exudative GN, and 1 patient demonstrated focal proliferative GN. Crescents were focally identified in 2 (25%) biopsies. By definition, immunofluorescence in all 8 cases showed co-dominant IgA and C3 staining.

Six of the 8 patients were treated with antibiotic therapy, and the 2 patients with infected hardware also underwent removal of their infection sources. At last follow-up, 5 (63%) patients required renal replacement therapy in the form of hemodialysis (n = 4) or peritoneal dialysis (n = 1). Two patients had persistent chronic kidney disease at last follow-up, and 1 patient had recovery of renal function to baseline serum creatinine.

Discussion

GN related to staphylococcal infection has become increasingly recognized as a unique but relatively uncommon (<1% of biopsies in most series) form of IRGN over the past 2 decades.2, 5 Unlike GN related to streptococcal infection, staphylococcal IRGN (S-IRGN) is often seen concurrently with an active staphylococcal infectious process, and thus treatment is typically focused on targeting the infection.6, 7 Early descriptions of S-IRGN primarily focused on patients with underlying diabetes mellitus; however, as the incidence of staphylococcal infections has continued to rise in the developed world,2 cases of S-IRGN in nondiabetic patients have also become increasingly recognized.4, 8 The 5 patients in our study (only 1 of whom was diabetic) had a wide variety of active staphylococcal infections at the time of biopsy, including superficial skin infections and deep seated infections with bacteremia. In addition, all showed an endocapillary proliferative and exudative pattern of injury, and 4 of the 5 patients had focal crescents. Histologically, S-IRGN has a limited spectrum of glomerular injury patterns, including diffuse proliferative and/or exudative, mesangial proliferative, membranoproliferative, and crescentic GN.3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11 Immunofluorescence staining typically highlights immune complex deposits that show either dominant or co-dominant coarse granular staining for IgA and C3 frequently along the glomerular capillaries and in the mesangium.3, 8, 11 Ultrastructural findings in S-IRGN include mesangial, and less frequently, subendothelial electron dense deposits, and in most cases, with a variable frequency (31%−100%) of subepithelial hump-like and intramembranous deposits.3, 4, 12

In this study, we described a subset of S-IRGN patients with IgA-dominant deposits and features of cryoglobulinemic GN; a finding that has been rarely reported. Satoskar et al. described focal hyaline pseudothrombi in 3 of 8 patients, all of whom had more severe endocapillary hypercellularity.3 Worawichawong et al. identified focal hyaline pseudothrombi in 2 of 7 cases of S-IRGN, all of whom showed a diffuse proliferative and exudative pattern of injury.4 The 5 cases of S-IRGN identified in this study represented 1.9% of native biopsies that showed GN with IgA-dominant deposits and 16% of S-IRGN cases during the study period. The presence of cryoglobulinemia was confirmed in 1 patient, whereas 2 patients had negative cryoglobulin assays. Patient #3 had an apparently transient type II mixed cryoglobulinemia, with cryoprecipitate containing IgA-λ, IgG, and IgM. In the 2 previous studies that reported S-IRGN cases with cryoglobulin-like features, only 1 patient had a documented positive cryoglobulin assay, and typing was not available.3 Clinically, testing for cryoglobulinemia can be difficult because temperature regulation from collection to specimen processing is required and frequently not achieved. These difficulties can result in false negative results.13, 14 Cryoglobulinemic GN with IgA-dominant deposits has been reported in association with underlying IgA-λ expressing lymphoproliferative disorders.15, 16 The patients in our cohort showed polytypic staining of IgA deposits by immunofluorescence microscopy, and most of those who underwent SPEP and/or immunofixation electrophoresis testing showed a polyclonal increase in IgA without monoclonal protein. One patient did have serum testing suggestive of monoclonal IgA-λ; however, repeat testing was negative, arguing in favor of a transient event, which was likely related to the underlying infectious process and associated with an inflammatory stimulus. Cryoglobulins containing IgA were reported in a high proportion of patients with IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein Purpura); however, this finding was not reproduced in other studies.17 Patient #2 in our study had an active HCV infection in addition to MSSA osteomyelitis and bacteremia. Cryoglobulinemic GN in the setting of HCV infection is most often a result of mixed cryoglobulinemia with monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG without IgA.18, 19, 20 The presence of dominant IgA staining in this report argued against HCV as the underlying cause of cryoglobulinemic GN in this patient. Outcomes in patients with IgA-dominant IRGN with cryoglobulinemic features appeared similar to those without these features. Compared with a small cohort of patients without cryoglobulinemic features, there was a similar rate of progression to end-stage kidney disease (80% vs. 63%) despite adequate antibacterial therapy. Previous studies of IgA-dominant IRGN also showed poor renal outcomes in most patients.3, 4

The pathophysiology and mechanism of cryoglobulinemia in the setting of staphylococcal infection has not been studied. In the setting of HCV infection, cryoglobulin production is likely related to activation of B lymphocytes after an interaction with HCV viral particles directly with B cells and release of B-cell activating factor by dendritic cells.21, 22 B-cell activation can lead to clonal expansion and monotypic IgM production with rheumatoid factor-like properties.22, 23, 24 Initial reports of S-IRGN postulated a role for staphylococcal superantigens in GN.5 The presence of superantigens, which cause over-activation of the immune system via interaction with the major histocompatibility complex on antigen-presenting cells, can result in activation of T cells and may also play a role in B-cell activation and antibody production.5 There is some evidence that staphylococcal enterotoxin B can result in B-cell activation and autoantibody formation.25 Further study is needed to identify the role (if any) of bacterial superantigens in B-cell activation and cryoglobulin production.

In summary, we presented a small group of patients with an uncommon manifestation of S-IRGN, highlighted by acute endocapillary and extracapillary GN with hyaline capillary wall and luminal deposits suggestive of cryoglobulinemia. All cases demonstrated dominant or co-dominant immunofluorescence staining for IgA, all patients had active S aureus infections at the time of biopsy, and 80% of patients had end-stage kidney disease at last follow-up. Cryoglobulinemic features were not identified in patients with noninfectious IgA-dominant GN. This finding should initiate a thorough clinical evaluation for an active bacterial infection because prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy might be required to remove the potential source of bacterial antigen driving this severe form of immune complex-mediated GN.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Brodsky S.V., Nadasdy T. Infection-related glomerulonephritis. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;169:153–160. doi: 10.1159/000313950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasr S.H., Markowitz G.S., Stokes M.B. Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the modern era: experience with 86 adults and review of the literature. Medicine. 2008;87:21–32. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e318161b0fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoskar A.A., Nadasdy G., Plaza J.A. Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis mimicking IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1179–1186. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worawichawong S., Girard L., Trpkov K. Immunoglobulin A-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: frequent occurrence in nondiabetic patients with Staphylococcus aureus infection. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koyama A., Kobayashi M., Yamaguchi N. Glomerulonephritis associated with MRSA infection: a possible role of bacterial superantigen. Kidney Int. 1995;47:207–216. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glassock R.J., Alvarado A., Prosek J. Staphylococcus-related glomerulonephritis and poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: why defining “post” is important in understanding and treating infection-related glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:826–832. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meehan S.M. Postinfectious versus infection-related glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:725–726. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasr S.H., Markowitz G.S., Whelan J.D. IgA-dominant acute poststaphylococcal glomerulonephritis complicating diabetic nephropathy. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S.Y., Bu R., Zhang Q. Clinical, pathological, and prognostic characteristics of glomerulonephritis related to staphylococcal infection. Medicine. 2016;95:e3386. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasr S.H., D'Agati V.D. IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a new twist on an old disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119:c18–c25. doi: 10.1159/000324180. discussion c26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoskar A.A., Suleiman S., Ayoub I. Staphylococcus infection-associated GN - spectrum of IgA staining and prevalence of ANCA in a single-center cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:39–49. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05070516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas M., Racusen L.C., Bagnasco S.M. IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a report of 13 cases with common ultrastructural features. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motyckova G., Murali M. Laboratory testing for cryoglobulins. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:500–502. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargur R., White P., Egner W. Cryoglobulin evaluation: best practice? Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47(Pt 1):8–16. doi: 10.1258/acb.2009.009180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rollino C., Dieny A., Le Marc'hadour F. Double monoclonal cryoglobulinemia, glomerulonephritis and lymphoma. Nephron. 1992;62:459–464. doi: 10.1159/000187099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vignon M., Cohen C., Faguer S. The clinicopathologic characteristics of kidney diseases related to monotypic IgA deposits. Kidney Int. 2017;91:720–728. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Fuentes M., Chantler C., Williams D.G. Cryoglobulinaemia in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. BMJ. 1977;2:163–165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson R.J., Gretch D.R., Yamabe H. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:465–470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasquariello A., Ferri C., Moriconi L. Cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus. Am J Nephrol. 1993;13:300–304. doi: 10.1159/000168641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tedeschi A., Barate C., Minola E., Morra E. Cryoglobulinemia. Blood Rev. 2007;21:183–200. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosa D., Saletti G., De Gregorio E. Activation of naive B lymphocytes via CD81, a pathogenetic mechanism for hepatitis C virus-associated B lymphocyte disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18544–18549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509402102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dammacco F., Sansonno D. Therapy for hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1035–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charles E.D., Brunetti C., Marukian S. Clonal B cells in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia contain an expanded anergic CD21low B-cell subset. Blood. 2011;117:5425–5437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visentini M., Conti V., Cagliuso M. Persistence of a large population of exhausted monoclonal B cells in mixed cryoglobuliemia after the eradication of hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:729–735. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J., Yang J., Lu Y.W. Possible role of staphylococcal enterotoxin B in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Viral Immunol. 2015;28:354–359. doi: 10.1089/vim.2015.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]