Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is an incurable disease with poor prognosis and unknown etiology. The poor clinical outcome is associated with enhanced microbial burden in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from IPF patients. However, whether microbes from the respiratory tract fluid cause the disease remains uncertain. Tissue-associated microbes can influence host physiology in health and disease development. The aim of this study was to evaluate the existence of microbes in lung fibrotic tissues. We evaluated the microbial community in lung tissues from IPF and from human transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) transgenic mice with lung fibrosis by oligotyping. We also evaluated the microbial population in non-tumor-bearing tissues from surgical specimens of lung cancer patients. The phyla Firmicutes and the genus Clostridium tended to be predominant in the lung tissue from IPF and lung cancer patients. Oligotyping analysis revealed a predominance of bacteria belonging to the genera Halomonas, Shewanella, Christensenella, and Clostridium in lung tissue from IPF and lung cancer. Evaluation of the microbial community in the lung tissue from mice revealed abundance of Proteobacteria in both wild-type (WT) littermates and transgenic mice. However, the genus Halomonas tended to be more abundant in TGF-β1 transgenic mice compared to WT mice. In conclusion, this study describes tissue-associated microbes in lung fibrotic tissues from IPF patients and from aging TGF-β1 transgenic mice.

Keywords: fibrosis, microbes, epithelial cells, cancer, mouse model, lung tissue

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and fatal disease with a median survival of only 2–4 years following diagnosis, and thus it is considered to be more lethal than many types of cancer (King et al., 2011). No definite etiology of IPF has been identified and no effective therapy that shows survival benefit is available (King et al., 2011). It is currently thought that the disease is the result of a chronic/repetitive injury and dysfunction of alveolar epithelial cells triggered by environmental or occupational factors (e.g., pollutants, dusts, gastric aspirates, and cigarette smoke) in a genetically predisposed host (Richeldi et al., 2017). Epithelial injury is apparently followed by increased expression of pro-fibrotic cytokines and growth factors, accelerated apoptosis of the alveolar epithelium, abnormal accumulation of activated myofibroblasts, and excessive deposition of extracellular matrix proteins in the lungs (Richeldi et al., 2017). The mechanism of the lung epithelial dysfunction induced by the gene and environmental risk factors is unclear. Recent studies suggest that imbalance of the lung microbial community or dysbiosis may play a role in the process of chronic injury and activation of lung epithelial cells in IPF (Molyneaux and Maher, 2013; Hewitt and Molyneaux, 2017). The association of the lung microbiota with acute exacerbation, clinical progression of the disease, risk of death, decline in pulmonary function, persistent elevation of the host immune response and with the progression-free survival, and fibroblast responsiveness provides strong evidence on the clinical and pathogenic relevance of the lung microbiota in IPF (Molyneaux et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). However, whether the lung microbial population is the cause or consequence of IPF remains unknown.

Studies on the gut microbiome have shown that mucosa-associated microbes are relatively stable overtime and that bacteria directly interacting with organ tissue can affect host response in health and disease development (Backhed et al., 2005). Most studies on the microbiome in IPF have used bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples for microbial analysis (Han et al., 2014; Molyneaux et al., 2014); that is, most isolated microbes were residing in the airway lumen. Another limitation of past studies is the use of methods with restricted taxonomic resolution, and therefore only microorganisms commonly found in healthy individuals could be detected in the IPF lung (Han et al., 2014; Molyneaux et al., 2014; Kitsios et al., 2018). In this study, we hypothesized that the use of a high-resolution computational method would allow identification of microbial communities previously undescribed in the lung microbiome. To test this hypothesis, we prepared and sequenced 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons from lung tissue samples and used oligotyping, a computational method with high resolution (Eren et al., 2013, 2014) to distinguish microbial communities in fibrotic tissues from patients with IPF and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 transgenic mice with pulmonary fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study comprised six patients with IPF, three patients with lung adenocarcinoma, two patients with collagen vascular disease-associated interstitial lung disease, one subject with pneumothorax, and three healthy subjects (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Diagnosis of IPF and lung cancer was done following accepted international criteria (Travis et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2012).

All subjects provided written informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committees for Clinical Investigation of Mie University (Approval No. 2707, March 7, 2014), Matsusaka Municipal Hospital (approval dated June 11, 2014), and Mie Chuo Medical Center (Approval No. 2014-6; September 2, 2014) and conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample Collection From All Subjects

None of the subjects included in the study received any therapy with antibiotics 6 weeks prior to sample collection. Bronchoscopy study was performed following guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and BALF samples were collected as previously described (Meyer et al., 2012; Han et al., 2014). Aliquots of unprocessed BALF collected into sterile tubes were immediately placed on ice, centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min and each pellet was frozen at -80°C until DNA extraction. Unstimulated saliva was collected from all study participants after thorough flushing with a water rinse. The subjects were instructed to expel continuously spit that pools on the floor of the mouth on sterile plastic tubes, transferred to sterile tubes, centrifuged as described above and the pellet stored at -80°C until DNA extraction. Histopathological diagnosis of IPF was done in five patients through lung samples obtained by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), which was performed following standard sterile surgical conditions (Morris and Zamvar, 2014). Lung samples obtained by VATS from three IPF patients were available for microbial analysis. Lung histological samples from lung cancer patients were obtained from the resected lung tumor after completion of the therapeutic surgical procedures (Supplementary Table 1). The normal non-tumoral regions of the resected lobe from lung cancer patients were used for the preparation of bacterial genomic DNA.

Animals

Human TGF-β1 transgenic mice backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for more than 10 generations were previously characterized and wild-type (WT) littermates were used as controls (D’Alessandro-Gabazza et al., 2012). All animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment and subjected to a 12-h light/dark cycle in the animal house of Mie University. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) of mice was performed as previously described (D’Alessandro-Gabazza et al., 2012). The Committee for Animal Investigation of Mie University approved the experimental protocols (Approval No. 24-50) and all procedures were performed in accordance with approved institutional guidelines.

Experimental Design and Sample Collection From Mice

Transforming growth factor-β1 transgenic mice (females, n = 7, males, n = 5) of more than 20 weeks of age and with advanced pulmonary fibrosis on micro-CT examination were used in the experiments. WT (females, n = 5; males, n = 2) littermates with normal findings on micro-CT examination were used as controls. For microbial analysis of lung tissue, mice were euthanized by an overdose (>120 mg/kg) of sodium pentobarbital administered by intraperitoneal injection and the lungs were sampled using sterilized instruments and under sterile surgical conditions. Excised lung specimens were placed into sterile tubes and stored at -80°C until analysis.

DNA Isolation From Samples

To extract DNA from BALF and saliva, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the pellets were suspended in a total of 100 μl saline and transferred to 2-ml bead beating tubes (Mo Bio). DNA was extracted using the Soil DNA Isolation Kit, Power Soil (Mo Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. DNA concentration was quantified using the NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies). Frozen lung tissues were placed in a sterile plastic dish, dissociated, cut and finely minced using sterile scalpels and then DNA was extracted following the same procedure described above and prepared for subsequent analysis.

Small Subunit Ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid (SSU rRNA) Hypervariable Tag Sequencing

Amplicon libraries for the 16S rRNA gene V1–V3 hypervariable regions were constructed using a set of primers targeting the hypervariable regions V1–V3 (V123), using a mixture of four forward primers V123F1234, and one reverse primer V123R, as previously described (Trompette et al., 2014). The products obtained from six separate reactions were pooled and purified using Gel Band Purification Columns (GE Healthcare, United Kingdom), and the DNA concentration was determined using the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, United States). Sample-specific, 12-base barcodes were used to tag each PCR product prior to high-throughput sequencing. The uniquely tagged, pooled DNA samples were immobilized on DNA capture beads, amplified through emulsion-based clonal amplification (emPCR), and sequenced in a 454 Life Sciences Genome Sequencer FLX (Roche Diagnostics) at the W.M. Keck Center for Comparative and Functional Genomics, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and at the Microarray Technologies and BIOInfOSU Core Facility Services at Oklahoma State University, Stillwater. There are reports showing comparable results obtained using either 454 or the now broadly used Illumina MiSeq for the scrutiny of microbial biodiversity through 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Tremblay et al., 2015; Castelino et al., 2017).

Community Analysis

514,985 quality-filtered 16S rRNA sequences from 454 pyro-sequencing were processed using the QIIME pipeline (Caporaso et al., 2010). Reads with lengths below 200 nucleotides and quality scores under 25 were excluded from further analysis. No mismatches were allowed in the forward primer. Resulting quality-controlled sequences were denoised using default settings and binned into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% sequence similarity cutoff using uclust 1.2.22 as OTU picking method (Edgar, 2010; Kunin et al., 2010). The cluster seed was used as representative sequence. Chimeric sequences were detected with the Chimera Slayer algorithm and excluded from subsequent analysis. Non-chimeric sequences were aligned with the PyNAST tool using as reference the Greengenes core set alignment (DeSantis et al., 2006; Caporaso et al., 2010). Taxonomy assignations were inferred through comparisons with both the RDP and BLASTn databases (Altschul et al., 1990; Cole et al., 2009). Rarefaction analysis was performed at a depth of 1000 sequences by sample in order to remove the heterogeneity of the number of sequences by sample prior to calculation of alpha and beta diversity statistics. Alpha diversity was measured through Shannon (measurement of the diversity), Chao1 (richness), and equitability (evenness) indices. Beta diversity was calculated using weighted and unweighted UniFrac metrics. QIIME data were imported to the R software for further statistical inference (R Core Team, 2015). Barplots and boxplots were created with ggplot2 after exclusion of taxa with relative abundances under 1% (Wickham, 2009).

Staining of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen

Staining of PCNA was performed at Biopathology Institute Corporation (Oita, Japan) using rabbit polyclonal anti-PCNA antibody (Abcam, Tokyo, Japan) and biotin-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody according to standard methods.

Oligotyping Analysis

QIIME data were used as input for the oligotyping pipeline in order to determine oligotypes within the taxa contributing to variation among samples (Eren et al., 2013). Each oligotype was required to appear in at least one sample (-s 1) and have a minimum substantive abundance of 10 (-M 10). These parameters were chosen empirically based on the purpose of the analysis and corresponded to the consensus values giving consistent results for each taxonomic group. Matrix counts were normalized within each sample for comparative analysis and imported into R for statistical analysis and graphics generation. For oligotyping, we performed quality filtering of raw sequencing data generated by 454 sequencing technology. Supplementary Table 2 summarizes all custom parameters utilized and the number of oligotypes generated for each taxa analyzed. Bacterial DNA sequences are available at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession KAFK00000000.

Statistical Analysis

Probability distribution of data was determined using the function descdist from the fitdistrplus package (Delignette-Muller and Dutang, 2015) and uniformity of variance was tested with the Levene test within the car package in R (Fox and Weisberg, 2011). The human groups for comparison included three healthy subjects, six IPF, and three lung cancer patients, and the murine groups included 7 WT and 12 TGF-β1 TG mice. Differences between experimental groups were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to evaluate differences in oligotype profiles in the R (package stats) between the study groups by sample source. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed to valuate variations in the dataset (Anderson, 2001). A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significance.

Results

Microbial Communities at the Phylum and Genus Level

Luminal (BALF) and Saliva Samples

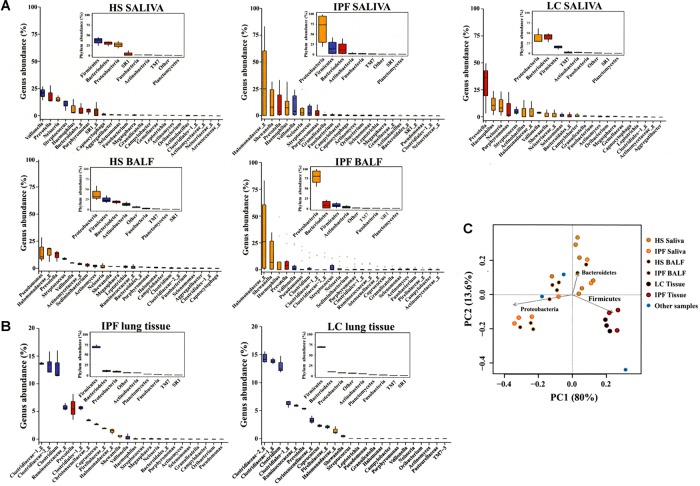

Analysis of bacterial communities by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing revealed a trend toward enhanced proportion of Proteobacteria in saliva and BALF of IPF patients compared to healthy subjects (Figure 1A and Supplementary Tables 3, 4). Proteobacteria tended to be predominant in saliva from lung cancer patients compared to healthy subjects. Subsequent evaluation at the genus level showed that Halomonadaceae and Shewanellaceae, both members of the Proteobacteria, tended to be more dominant in saliva and BALF from IPF patients compared to healthy subjects. The main genera detected in saliva and BALF of IPF patients were an unknown genus belonging to the Halomonadaceae (hereinafter referred to as Halomonadaceae_g), and Shewanella, Prevotella, Haemophilus, Veillonella, Neisseria, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, and Streptococcus (Figure 1A and Supplementary Tables 3, 4).

FIGURE 1.

Community profiles of saliva, BALF, and lung tissue in controls and patients. Saliva, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (A), and lung tissues (B) were sampled from IPF and LC patients, and saliva and BALF (A) from HS to isolate genomic DNA, amplify the V123 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene through high-throughput sequencing and taxonomic profiling. The abundance variation box plots as determined by read abundance for the 38 most abundant genera in IPF and LC patients are displayed and colored by taxonomic affiliation at the phylum level. Corresponding insets exhibit phylum abundance box plots. Principal component analysis (PcoA) was also calculated (C). Saliva (n = 6), BALF (n = 3), and lung tissue (n = 3) samples were available from IPF patients; saliva (n = 3) and lung tissue (n = 3) samples were available from LC patients. “Other samples” described in (C) are BALF samples from patients with collagen vascular disease-associated interstitial lung disease (n = 2) and lung tissue sample from a patient with pneumothorax (n = 1). BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; LC, lung cancer; HS, healthy subjects.

Tissue Samples

Pulmonary tissue samples from IPF and lung cancer patients displayed similar bacterial taxonomic profiles. Lung tissue samples were characterized by a large proportion of Firmicutes and a high percentage of unclassified bacteria (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 5). There was a small proportion of Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and other minority phyla. Main families within the Firmicutes included Clostridiaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, two new families within the Clostridiales, and Christensenellaceae. A more detailed analysis showed two unknown Clostridiaceae genera (Clostridiaceae-1_g, Clostridiaceae-2_g) and Clostridium as the predominant genera detectable in lung tissue from IPF (p > 0.05) and lung cancer patients (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 5). None of the differences among taxonomic groups between lung cancer and IPF patients were significant.

An overall evaluation of the phylogenetic diversity among human groups and between TGF-β1 and WT murine groups disclosed no significant difference (Supplementary Tables 6, 7). However, the microbial population of lung tissue samples showed a significant phylogenetic divergence compared to that of BALF and saliva samples (Supplementary Table 8).

Principal Component Analysis

The principal component analysis (PCoA) revealed that variation among samples was mostly due to abundance of the main detected bacterial phyla, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes without clear associations to healthy and diseased states, but with a tendency toward an enrichment of Proteobacteria in saliva and BALF from IPF patients, and of Firmicutes in lung tissues from lung cancer and IPF patients (Figure 1C). In addition, the PCoA revealed clustering of tissue samples from both lung cancer and IPF subjects, indicating that lung tissue communities from either condition display similar bacterial taxonomic profiles (Figure 1C).

Bacterial Oligotypes

Luminal and Saliva Samples

To further resolve the bacterial diversity below the genus level, microbial oligotypes of the most dominant genera were analyzed by sample source. Oligotypes of Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Veillonella, Prevotella, and Pseudomonas were identified mainly in airway luminal samples (BALF, saliva) (Supplementary Figures 2A–C and Supplementary Table 2).

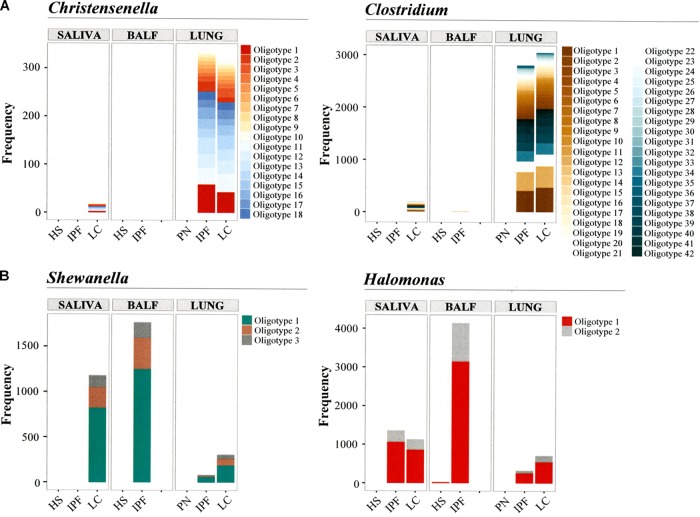

Tissue Samples

Clostridium oligotypes were dominant in lung tissues from IPF and lung cancer patients (Figures 2A,B). Oligotypes of Shewanella and an undescribed bacteria of Halomonadaceae genus (Halomonadaceae_g) were detected in tissue samples from IPF and lung cancer patients, as well as in the luminal samples (Figures 2A,B). We also detected several oligotypes of unknown Christensenellaceae genera (Christensenellaceae_g). The most prevalent Christensenellaceae_g oligotype (i.e., oligotype 1, Figure 2A) in IPF and LC patients displayed the highest similarity with an uncultured member of the Clostridiales isolated from the rumen (Supplementary Table 2). The main oligotypes within Clostridium in lung tissues from IPF and lung cancer patients (oligotypes 1, 12, and 41; Figure 2A and Supplementary Table 2) shared similarities ranging from 99 to 100% with Clostridium butyricum strain JDY6D1. Shewanella oligotypes in lung tissues from IPF and lung cancer patients were predominated by oligotypes 1 and 2, which exhibited close to 100% similarity with the Shewanella haliotis strain 0315 (Figure 2B and Supplementary Table 2). These oligotypes also dominated in saliva and BALF from lung cancer and IPF patients. For the yet uncharacterized genus Halomonadaceae_g, the most detected oligotype (oligotype 1) showed 100% similarity with an uncultured Halomonas strain isolated from the intestinal microbiota of Rutilus rutilus, the common roach (Figure 2B and Supplementary Table 2). This oligotype was also detectable in saliva from both IPF and lung cancer patients in addition to BALF from IPF patients.

FIGURE 2.

Oligotyping of microbial communities. Individual nucleotide positions were evaluated by Shannon entropy to identify the most frequent microbial community oligotypes across samples. Oligotypes of Christensenella and Clostridium (A), and oligotypes of Shewanella and Halomonas (B) were detected. Saliva (n = 6), BALF (n = 3), and lung tissue (n = 3) samples were available from patients with IPF; saliva (n = 3) and lung tissue (n = 3) samples were available from LC patients. Lung tissue sample was available from one patient with PN. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; HS, healthy subjects; PN, pneumothorax patient. Frequency in the y-axis represents the normalized oligotype counts.

An overall evaluation of statistical differences in the oligotype profiles for Christensenellaceae, Clostridium, Shewanella, and Halomonadaceae was performed between the study groups (healthy subjects/pneumothorax, IPF, lung cancer) by sample source (saliva, BALF, lung tissue). The analysis showed that the oligotype profiles of Clostridium (p < 0.001) in saliva could significantly differentiate groups as compared to other sample sources. There was tendency but not significant difference by sample source in the oligotype profiles of Shewanella or Halomonadaceae, which was likely due to the low number of subjects within each group (Supplementary Table 9).

Bacterial Populations in Aging TGF-β1 Transgenic Mouse With Pulmonary Fibrosis

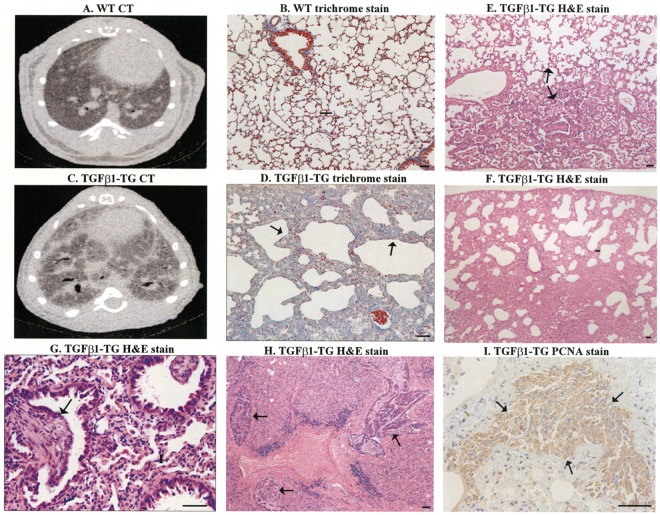

To demonstrate whether a fibrotic environment favors the growth of specific groups of lung microbiota, we evaluated the microbial communities in lung tissue from mice overexpressing the human profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 specifically in the lungs (D’Alessandro-Gabazza et al., 2012). Similar to the disease in humans, aged (>30 weeks) TGF-β1 transgenic mice spontaneously develop pulmonary fibrosis with a progressive and fatal course (Figures 3A–D). The lung histopathologic findings are characterized by lung scarring, and honeycomb cysts alternating with areas of less affected parenchyma (Figures 3D–F). The lungs of transgenic mice also exhibit fibroblast foci-like areas and, at late stages, lung cancer complication (Figures 3G–I).

FIGURE 3.

Pulmonary fibrosis in transgenic (TG) mice overexpressing human transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1. CT and trichrome stain of lung tissues from WT mice (A,B) and TGF-β1 mice (C,D, arrows). H&E stain showed areas of fibrotic changes alternate with areas with less affected parenchyma (E, arrows), honeycombing-like cysts with disruption of lung parenchyma (F), and fibroblastic foci-like structures (G, arrow), and multiples areas with adenocarcinoma (H, arrows). There is increased staining of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in cancerous areas (I, arrows). Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

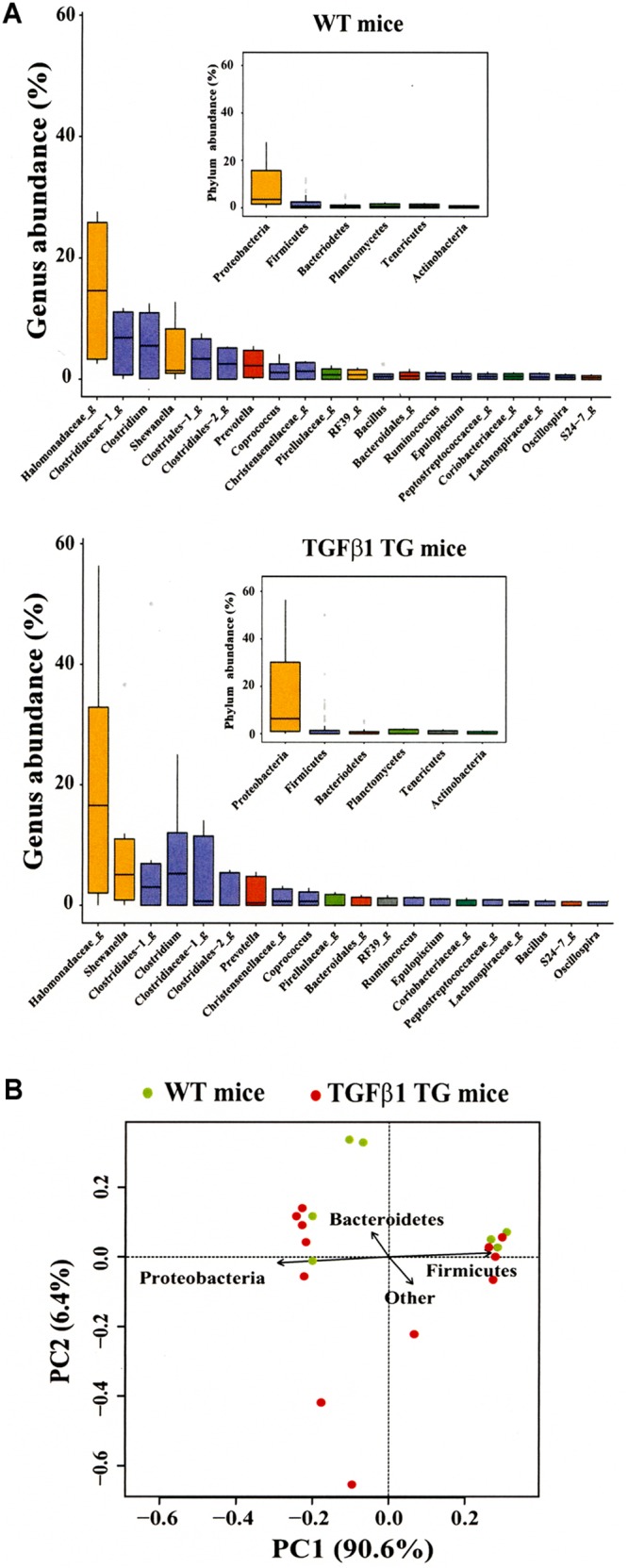

Evaluation of bacterial composition based on 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing revealed relative abundance of Proteobacteria in both WT littermates and transgenic mice; however, at the genus-level, a trend toward an increase in members of Halomonadaceae and Shewanellaceae was observed in TGF-β1 transgenic mice compared to their WT counterparts (Figure 4A). The PCoA explained a 97% of the variation among samples, which was mostly related to abundance of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, without clear associations between WT and TGF-β1 transgenic mice (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Community profiles of lung tissue in wild-type (WT) and TGF-β1 transgenic (TG) mice. Analysis of microbial composition of lung tissues from both WT and TGF-β1 TG mice at the phylum and genus level (A). PCoA was also performed (B).

Alpha and Beta Diversities

The distribution pattern of the alpha diversity was displayed using the Faith’s phylogenetic diversity metric (Faith, 1992). There were no significant differences among the different human and mouse groups (Supplementary Figures 3A,B). Beta diversity of the human and mouse groups was evaluated above by PCoA of weighted unifrac distances and by PERMANOVA.

Discussion

Lung Sampling, Risk of Contamination, and Microbial Communities

Recent studies have demonstrated that the normal lung is not sterile and the existence of a healthy lung microbiome (Moffatt and Cookson, 2017). However, the risk of microbial contamination or false positive finding is still a major concern during lung molecular microbiome studies. Contamination can occur during specimen sampling, DNA extraction, amplicon preparation, and sequencing (Tanner et al., 1998; Salter et al., 2014). Bronchoscopy is generally used for sampling. During the procedure, a sterilized bronchoscope is advanced through the oral or nasal cavity, pharynx, and vocal cords before wedging into a middle or lingular lobe airway, thus during the procedure there is a risk of carrying contaminants from the oropharyngeal region to the lower respiratory tract (Han et al., 2014). Nonetheless, well-conducted investigations of bacterial topography in healthy human airways have demonstrated that contamination during oropharyngeal passage of the bronchoscope is actually minimum, thus providing validation for the use of bronchoscopy in lung microbiome studies (Charlson et al., 2011; Dickson et al., 2017). Based on the reported bacterial topography data we can assume that the lung luminal and tissue-resident microbes described here have migrated primarily by microaspiration and additionally by mucosal dispersion from the upper respiratory track (Dickson et al., 2017). The similar frequency of the BALF microbial communities at phylum level in healthy individuals and IPF patients between our findings and previous reports suggests that contamination was probably minimum in our present study (Molyneaux et al., 2017; Takahashi et al., 2018). The risk of contamination of lung tissues sampled from IPF and lung cancer patients, and of the lungs excised from WT and TGF-β1 TG mice was also minimum, at least during sampling, because sampling was performed under sterile surgical conditions. Interestingly, there was a predominance of Firmicutes in the lung tissue from both IPF and lung cancer patients, whereas Proteobacteria and Firmicutes were abundance in the lung tissue from human TGF-β1 TG mice. We have no explanation for the resemblance of the lung tissue microbial population between IPF and lung cancer patients. However, it is worth noting here that common genetic and epigenetic aberrations have been also reported in both IPF and lung cancer patients (Vancheri et al., 2010; Vancheri, 2013; Vancheri and du Bois, 2013; Stella et al., 2014; Vancheri, 2015).

Oligotyping Versus Canonical Methods

In the present study, to test the hypothesis that a high resolution technique would identify so far undescribed microbial populations in the lungs, we used oligotyping, a computational method with high resolution, to evaluate the lung microbial community (Eren et al., 2013). Assignment of a microbial community analyzed by the 16S rRNA gene to a specific group is generally performed by comparing the DNA sequence to a reference database or by identifying OTUs from clustering sequences using an arbitrary similarity threshold (Wang et al., 2007; Huse et al., 2008, 2010; Liu et al., 2008; Schloss et al., 2009). However, each of these canonical approaches has important limitations. Reference-based classifications may fail to provide the real microbial diversity in a specific environment because of the lack of representative isolates in the database. On the other hand, the clustering approach may fail to identify microbial populations that differ from each other by small number of nucleotides, because researchers commonly use low similarity threshold to avoid random sequencing errors. Due to disadvantages of these canonical methods, we used here high-throughput sequencing followed by classification into groups that have identical sequences known as oligotypes. To determine oligotypes, the 16S rRNA gene sequences are aligned and the Shannon entropy is calculated to identify highly variable nucleotide positions. This high-resolution approach may allow the distinction between sequences differing by as little as a single nucleotide (Eren et al., 2014). In the present study, we performed oligotyping to clarify whether there are differential distribution patterns of oligotypes within our cohort groups. The results of this analysis disclosed the presence of several oligotypes of Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Veillonella, Pseudomonas, and Prevotella in BALF and saliva from both IPF and healthy subjects. More importantly, for the first time, various oligotypes of Christensenella and Clostridium were detected in lung tissue and a few oligotypes of Shewanella and Halomonas in both airway fluid and lung tissue from IPF and lung cancer patients, further suggesting the involvement of these microbial communities in fibrotic diseases.

Proposal of a Mechanistic Hypothesis of IPF Based on Current Findings

Genome-wide association studies have shown that aberrations of several genes including surfactant protein, telomerases, and mucin are associated with high risk of developing IPF (Fingerlin et al., 2013). On the other hand, growing evidence indicates that host genetic variations can influence the microbiome composition (Goodrich et al., 2014; Blekhman et al., 2015; Luca et al., 2018). Therefore, it is conceivable that genetic alterations affect the lung microbial composition in patients with IPF. Here, we identified members of the Christensenellaceae family in lung fibrotic tissues. Previous study has shown that Christensenella is the most heritable microbe in the gut (Goodrich et al., 2014); that is, its presence or absence depends on the host genetic variant. In addition, the presence of Christensenella appears to predict the coexistence of other bacteria because it is apparently able to drive changes in the microbial community (Goodrich et al., 2014). The identification of Christensenellaceae family members here suggests their potential role in remodeling of lung microbial diversity in IPF. On the other hand, there is a consensus that IPF is triggered by repetitive lung epithelial injury causing enhanced activation and/or accelerated apoptosis of the alveolar lining epithelium and by increased lung recruitment of myofibroblasts leading to increased collagen production and deposition (King et al., 2011; Bagnato and Harari, 2015). Here we showed that Halomonas and Shewanella coexist in the IPF lung. Based on the halophilic and pro-apoptotic properties of Halomonas (Martinez-Canovas et al., 2004; Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2011; Sagar et al., 2013) and sodium permeation-changing ability of Shewanella (Wang et al., 2008), we hypothesize that the presence of Shewanella increases extracellular levels of salt by blocking intracellular passage of sodium and thereby creating a propitious microenvironment for the growth of Halomonas. These halophilic bacteria secrete potent pro-apoptotic factors that may activate and subsequently induce increased apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2011; Sagar et al., 2013). Activated epithelial cells express several pro-fibrotic growth factors including TGF-β1, which may further stimulate the growth of Halomonas by promoting extracellular salt formation via inhibition of cell membrane expression of sodium and chloride channels (Supplementary Figure 4; Frank et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2014; Lutful Kabir et al., 2018).

The eventual detrimental role of a salty microenvironment in the pathophysiological scenario of IPF is supported by the following observations: (1) acute exacerbation of the disease in IPF patients is common following diagnostic bronchoalveolar lavage procedures in which a high volume of saline is used (Sakamoto et al., 2012), (2) increased circulating sodium chloride increases TGF-β1 expression (Hovater and Sanders, 2012), and (3) salt decreases the protective activity of mucin (Travis et al., 1999). The fact that mucin in turn can block the adverse effects of salt (Travis et al., 1999) may explain why IPF patients with a common risk polymorphism in MUC5B, associated with increased mucin production, have significantly improved survival (Peljto et al., 2013).

Study Limitations

One limitation is the small size of the IPF and lung cancer population. It is generally difficult to obtain lung tissue samples from IPF patients because diagnostic bronchoscopy procedures are frequently associated with exacerbation or with fatal consequences of the fibrotic disease (Sakamoto et al., 2012).

Conclusion

The discovery in the present study of a potentially pathogenic microbial community in direct association with lung tissue from IPF and TGF-β1 transgenic mice implicates this bacterial community in the pathogenesis of the fibrotic disease. The similarity between the microbial composition of the lung tissue from TGF-β1 TG mice with lung fibrosis and IPF suggests the potential usefulness of this mouse model for evaluating the role of the lung microbiome in the pathogenesis of IPF and for testing the therapeutic efficacy of antibiotics. However, further studies that examine tissues from a larger sample size and patients of different genetic backgrounds will help probe the observations made in this study. In addition, transplantation studies using TGF-β1 TG and germ-free mice would help confirm the impact of the lung microbiome in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.

Data Availability

Bacterial DNA sequences are available at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the Accession No. KAFK00000000.

Author Contributions

IC, ECG, and CND-G conceived the project, designed the study, wrote the manuscript, and supervised all phases of the investigation. IC, CM-G, SW, and RM performed the DNA sequencing and gene profiling. OH, FW, OT, TK, HF, and KF provided samples, interpreted clinical data, and supervised data analysis. MT, TY, and CND-G performed the sample collection and DNA extraction. KF and KN performed the microCT, genotyping, and additional microbial DNA extraction.

Conflict of Interest Statement

ECG, CND-G, and IC have issued a patent on this new discovery. ECG and TK have a patent on the TGF-β1 TG mouse used in this study.The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer KB and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Kakenhi Nos. 17K08442 and 18K08175), gift funds to IC and RM and also supported by the College of ACES Office of International Programs, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The funders had no role in study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01892/full#supplementary-material

References

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. J. (2001). Permutation tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 58 626–639. 10.1139/f01-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Ley R. E., Sonnenburg J. L., Peterson D. A., Gordon J. I. (2005). Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307 1915–1920. 10.1126/science.1104816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato G., Harari S. (2015). Cellular interactions in the pathogenesis of interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 24 102–114. 10.1183/09059180.00003214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekhman R., Goodrich J. K., Huang K., Sun Q., Bukowski R., Bell J. T., et al. (2015). Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol. 16:191. 10.1186/s13059-015-0759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7 335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelino M., Eyre S., Moat J., Fox G., Martin P., Ho P., et al. (2017). Optimisation of methods for bacterial skin microbiome investigation: primer selection and comparison of the 454 versus MiSeq platform. BMC Microbiol. 17:23. 10.1186/s12866-017-0927-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson E. S., Bittinger K., Haas A. R., Fitzgerald A. S., Frank I., Yadav A., et al. (2011). Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184 957–963. 10.1164/rccm.201104-0655OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Wang Q., Cardenas E., Fish J., Chai B., Farris R. J., et al. (2009). The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D141–D145. 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015). A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro-Gabazza C. N., Kobayashi T., Boveda-Ruiz D., Takagi T., Toda M., Gil-Bernabe P., et al. (2012). Development and preclinical efficacy of novel transforming growth factor-beta1 short interfering RNAs for pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 46 397–406. 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0158OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delignette-Muller M. L., Dutang C. (2015). fitdistrplus: an R package for fitting distributions. J. Stat. Softw. 64 1–34. 10.18637/jss.v064.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis T. Z., Hugenholtz P., Larsen N., Rojas M., Brodie E. L., Keller K., et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 5069–5072. 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. P., Erb-Downward J. R., Freeman C. M., Mccloskey L., Falkowski N. R., Huffnagle G. B., et al. (2017). Bacterial topography of the healthy human lower respiratory tract. mBio 8:e02287-16. 10.1128/mBio.02287-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren A. M., Borisy G. G., Huse S. M., Mark Welch J. L. (2014). Oligotyping analysis of the human oral microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E2875–E2884. 10.1073/pnas.1409644111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren A. M., Maignien L., Sul W. J., Murphy L. G., Grim S. L., Morrison H. G., et al. (2013). Oligotyping: differentiating between closely related microbial taxa using 16S rRNA gene data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4 1111–1119. 10.1111/2041-210X.12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith D. P. (1992). Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 61 1–10. 10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerlin T. E., Murphy E., Zhang W., Peljto A. L., Brown K. K., Steele M. P., et al. (2013). Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 45 613–620. 10.1038/ng.2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Weisberg S. (2011). An R Comparison to Applied Regression. Thousand Oaks, CL: SAGE Publications. 10.1074/jbc.M304882200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J., Roux J., Kawakatsu H., Su G., Dagenais A., Berthiaume Y., et al. (2003). Transforming growth factor-beta1 decreases expression of the epithelial sodium channel alphaENaC and alveolar epithelial vectorial sodium and fluid transport via an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278 43939–43950. 10.1074/jbc.M304882200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J. K., Waters J. L., Poole A. C., Sutter J. L., Koren O., Blekhman R., et al. (2014). Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 159 789–799. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. K., Zhou Y., Murray S., Tayob N., Noth I., Lama V. N., et al. (2014). Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2 548–556. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70069-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt R. J., Molyneaux P. L. (2017). The respiratory microbiome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Transl. Med. 5 250. 10.21037/atm.2017.01.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovater M. B., Sanders P. W. (2012). Effect of dietary salt on regulation of TGF-beta in the kidney. Semin. Nephrol. 32 269–276. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Ma S. F., Espindola M. S., Vij R., Oldham J. M., Huffnagle G. B., et al. (2017). Microbes Are Associated with Host Innate Immune Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196 208–219. 10.1164/rccm.201607-1525OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse S. M., Dethlefsen L., Huber J. A., Mark Welch D., Relman D. A., Sogin M. L. (2008). Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000255. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse S. M., Welch D. M., Morrison H. G., Sogin M. L. (2010). Ironing out the wrinkles in the rare biosphere through improved OTU clustering. Environ. Microbiol. 12 1889–1898. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02193.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King T. E., Jr., Pardo A., Selman M. (2011). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 378 1949–1961. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsios G. D., Rojas M., Kass D. J., Fitch A., Sembrat J. C., Qin S., et al. (2018). Microbiome in lung explants of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case-control study in patients with end-stage fibrosis. Thorax 73 481–484. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin V., Engelbrektson A., Ochman H., Hugenholtz P. (2010). Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ. Microbiol. 12 118–123. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Desantis T. Z., Andersen G. L., Knight R. (2008). Accurate taxonomy assignments from 16S rRNA sequences produced by highly parallel pyrosequencers. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:e120. 10.1093/nar/gkn491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca F., Kupfer S. S., Knights D., Khoruts A., Blekhman R. (2018). Functional genomics of host-microbiome interactions in humans. Trends Genet. 34 30–40. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutful Kabir F., Ambalavanan N., Liu G., Li P., Solomon G. M., Lal C. V., et al. (2018). MicroRNA-145 antagonism reverses TGF-beta inhibition of F508del CFTR correction in airway epithelia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 197 632–643. 10.1164/rccm.201704-0732OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Canovas M. J., Quesada E., Llamas I., Bejar V. (2004). Halomonas ventosae sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, denitrifying, exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 733–737. 10.1099/ijs.0.02942-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. C., Raghu G., Baughman R. P., Brown K. K., Costabel U., Du Bois R. M., et al. (2012). An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185 1004–1014. 10.1164/rccm.201202-0320ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt M. F., Cookson W. O. (2017). The lung microbiome in health and disease. Clin. Med. 17 525–529. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux P. L., Cox M. J., Wells A. U., Kim H. C., Ji W., Cookson W. O., et al. (2017). Changes in the respiratory microbiome during acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 18:29. 10.1186/s12931-017-0511-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux P. L., Cox M. J., Willis-Owen S. A., Mallia P., Russell K. E., Russell A. M., et al. (2014). The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190 906–913. 10.1164/rccm.201403-0541OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux P. L., Maher T. M. (2013). The role of infection in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 22 376–381. 10.1183/09059180.00000713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris D., Zamvar V. (2014). The efficacy of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lung biopsies in patients with interstitial lung disease: a retrospective study of 66 patients. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 9:45. 10.1186/1749-8090-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peljto A. L., Zhang Y., Fingerlin T. E., Ma S. F., Garcia J. G., Richards T. J., et al. (2013). Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA 309 2232–2239. 10.1001/jama.2013.5827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. M., Vadasz I., Wujak L., Wygrecka M., Olschewski A., Becker C., et al. (2014). TGF-beta directs trafficking of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC which has implications for ion and fluid transport in acute lung injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E374–E383. 10.1073/pnas.1306798111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richeldi L., Collard H. R., Jones M. G. (2017). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 389 1941–1952. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ruiz C., Srivastava G. K., Carranza D., Mata J. A., Llamas I., Santamaria M., et al. (2011). An exopolysaccharide produced by the novel halophilic bacterium Halomonas stenophila strain B100 selectively induces apoptosis in human T leukaemia cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89 345–355. 10.1007/s00253-010-2886-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar S., Esau L., Holtermann K., Hikmawan T., Zhang G., Stingl U., et al. (2013). Induction of apoptosis in cancer cell lines by the Red Sea brine pool bacterial extracts. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 13:344. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K., Taniguchi H., Kondoh Y., Wakai K., Kimura T., Kataoka K., et al. (2012). Acute exacerbation of IPF following diagnostic bronchoalveolar lavage procedures. Respir. Med. 106 436–442. 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter S. J., Cox M. J., Turek E. M., Calus S. T., Cookson W. O., Moffatt M. F., et al. (2014). Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol. 12:87. 10.1186/s12915-014-0087-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss P. D., Westcott S. L., Ryabin T., Hall J. R., Hartmann M., Hollister E. B., et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 7537–7541. 10.1128/AEM.01541-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella G. M., Inghilleri S., Pignochino Y., Zorzetto M., Oggionni T., Morbini P., et al. (2014). Activation of oncogenic pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl. Oncol. 7 650–655. 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Saito A., Chiba H., Kuronuma K., Ikeda K., Kobayashi T., et al. (2018). Impaired diversity of the lung microbiome predicts progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 19:34. 10.1186/s12931-018-0736-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M. A., Goebel B. M., Dojka M. A., Pace N. R. (1998). Specific ribosomal DNA sequences from diverse environmental settings correlate with experimental contaminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 3110–3113. 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis S. M., Conway B. A., Zabner J., Smith J. J., Anderson N. N., Singh P. K., et al. (1999). Activity of abundant antimicrobials of the human airway. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 20 872–879. 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis W. D., Brambilla E., Noguchi M., Nicholson A. G., Geisinger K. R., Yatabe Y., et al. (2011). International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6 244–285. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay J., Singh K., Fern A., Kirton E. S., He S., Woyke T., et al. (2015). Primer and platform effects on 16S rRNA tag sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 6:771. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trompette A., Gollwitzer E. S., Yadava K., Sichelstiel A. K., Sprenger N., Ngom-Bru C., et al. (2014). Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 20 159–166. 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancheri C. (2013). Common pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer. Eur. Respir. Rev. 22 265–272. 10.1183/09059180.00003613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancheri C. (2015). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer: do they really look similar? BMC Med. 13:220. 10.1186/s12916-015-0478-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancheri C., du Bois R. M. (2013). A progression-free end-point for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis trials: lessons from cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 41 262–269. 10.1183/09031936.00115112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancheri C., Failla M., Crimi N., Raghu G. (2010). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur. Respir. J. 35 496–504. 10.1183/09031936.00077309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lesko M., Badri M. H., Kapoor B. C., Wu B. G., Li Y., et al. (2017). Lung microbiome and host immune tone in subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with inhaled interferon-gamma. ERJ Open Res. 3 00008–2017. 10.1183/23120541.00008-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Garrity G. M., Tiedje J. M., Cole J. R. (2007). Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 5261–5267. 10.1128/AEM.00062-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. J., Yu R. C., Luo X., Zhou M. J., Lin X. T. (2008). Toxin-screening and identification of bacteria isolated from highly toxic marine gastropod Nassarius semiplicatus. Toxicon 52 55–61. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.04.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. (2009). Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 10.1007/978-0-387-98141-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Bacterial DNA sequences are available at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the Accession No. KAFK00000000.