Abstract

Introduction: Zymogen granule glycoprotein 2 (GP2) was demonstrated as first autoimmune mucosal target in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) associated with disease severity. Autoantibodies to four GP2 isoforms (aGP21−4) were found in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases but reactivity against specific GP2 epitopes has not been investigated in PSC yet. Hence, the prevalence of aGP21−4 and their association with the PSC phenotype for risk prediction were examined.

Methods: GP2 isoforms were stably expressed as glycosylphosphatidyl - inositol-anchored molecules in the membrane of HEp-2 cells and used as autoantigenic targets in indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). aGP21−4 IgA and IgG were detected by IFA in 212 PSC patients of four European university hospitals and 145 controls comprising 95 patients with cystic fibrosis and 50 healthy subjects.

Results: Combined aGP21 and aGP24 IgA testing with a sensitivity of 66.0% and a specificity of 97.9% resulted in the best diagnostic performance (Youden index: 0.64) regarding all aGP2 and combinations thereof. aGP24 IgA positivity is significantly associated with the presence of cirrhosis in PSC (p = 0.0056). Logistic regression revealed the occurrence of aGP21 IgA (odds ratio [OR] 1.38, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03–1.86) and aGP24 IgA (OR 1.52, 95%CI: 1.07–2.15) along with male gender (OR 0.51, 95%CI: 0.27–0.97) and older age (OR 1.03 95%CI: 1.01–1.05) as significant risks for the concomitant presence of cirrhosis in PSC.

Conclusions: Combined aGP21 and aGP24 IgA analysis is preferred to single aGP2 isoform analysis for sensitive PSC autoantibody testing. Positivity for aGP21 and aGP24 IgA is associated with cirrhosis in PSC and could be used for risk stratification.

Keywords: zymogen granule glycoprotein 2, primary sclerosing cholangitis, cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma, immunoglobulin A

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a chronic immune-mediated, life threatening, genetically predisposed, cholestatic liver illness, is associated with the co-occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in particular with the phenotype thereof (1, 2). The prevalence of PSC is estimated at up to 16.2 per 100,000 individuals and still rising (3, 4). There is a clinical need for markers predicting PSC severity and prognosis despite recent progress regarding the use of certain serum and bile proteins (5, 6). Further, IgA to zymogen granule glycoprotein 2 (GP2) was identified as a novel marker candidate for disease severity and cholangiocarcinoma in PSC (7, 8). Glycoprotein 2 is a microbe-sensing (9, 10) and immunomodulating molecule (11) with two major sources (pancreas and intestine) (12). Of note, GP2 was originally identified as a target of Crohn's disease (CD)-specific pancreatic antibodies (13, 14). Upon specific binding to FimH, GP2 interacts selectively with bacterial species including pathogens (10) and, thus, may determine both innate and acquired immune responses to the intestinal microbiota (11, 15). There is mounting evidence that mucosal interactions between the intestinal microbiota and host immune responses partake in the development of chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract (12, 16–18).

Since the first report of GP2's over-expression in the inflamed intestine of CD patients (13), several cross-sectional and prospective studies demonstrated the association of autoantibodies (autoAbs) to GP2 (aGP2) with the stricturing and/or stenosing CD phenotype and disease severity (18, 19), earlier surgical recurrence after first surgery (20), as well as de-novo development of CD in patients with suspected ulcerative colitis (UC) after ileal pouch surgery and development of subsequent pouchitis (21). Thus, autoimmunity to GP2 appears to be a stratification factor of the clinical phenotype in IBD (18).

Given the close association of PSC with IBD, the occurrence of aGP2 IgA in severe PSC (7) provided further evidence for the correlation of the mucosal loss of tolerance to GP2 with fibrostenotic changes as reported in IBD (22). Remarkably, a recent comprehensive retrospective outcome analysis of 7,121 PSC patients at 37 centers in Europe, North America, and Australia revealed that 70% of them developed IBD at some point (1). Conversely, PSC appeared to be underestimated around three-fold in long-term IBD and to progress in subclinical IBD patients (23).

In total, four human GP2 isoforms (GP21−4) were identified (18, 24) and respective autoAbs detected in patients with IBD which demonstrated differing test performances by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (20, 25, 26). Hence, stable HEp-2 cell-lines expressing GP2 isoforms as glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane molecules and one cell line with an empty vector as control were generated to elucidate the role of loss of tolerance to GP2 isoforms in PSC. Consequently, IgG and IgA aGP21−4 by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) in patients with PSC and controls were determined.

Methods

Patients

Patients with PSC were recruited from four European university hospitals specialized in autoimmune liver diseases (Table 1). All PSC patients were examined clinically and endoscopically for concomitant IBD and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). The diagnosis of PSC and IBD was based on clinical, radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic evaluation (27, 28, 29).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients and controls.

| n | Age (IQR) | f (%) | IBD (%) | CD (%) | UC (%) | AIH (%) | Cirrhosis (%) | CCa (%) | LTx (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC | 212 | 43.0 (23.3) | 70 (33.0) | 136 (64.2) | 17 (8.0) | 119 (56.1) | 20 (9.4) | 86 (31.6) | 5* (3.7) | 81 (38.2) |

| Berlin | 23 | 52.5 (17.5) | 6 (26.1) | 19 (82.6)§3 | 2 (8.7) | 17 (73.9) | 1 (4.3) | 19 (82.6) | 0 | 19 (82.6) |

| Hamburg | 30 | 50.0 (17.3) | 18 (60.0)§2 | 15 (50.0) | 4 (13.3) | 11 (36.7)§5 | 5 (16.7) | 3 (10.0)§6 | 0 | 0 |

| London | 83 | 46.3 (18.7) | 23 (27.7) | 53 (63.9) | 1 (1.2)§4 | 52 (62.7) | 5 (6.0) | 49 (59.0)§8 | 5 (6.0) | 57 (68.8) |

| Debrecen | 76 | 34.1 (21.6)§1 | 23 (30.3) | 49 (64.5) | 10 (13.2) | 39 (51.3) | 9 (11.8) | 15 (19.7)§7 | 0 | 6 (7.9)§9 |

| Controls | 145 | 26.9 (22.1)& | 63 (43.4) | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0 | 0 |

| CF | 95 | 15.6 (20.9)& | 44 (46.3)$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0 | 0 |

| HS | 50 | 36.0 (18.0) | 19 (38.0) | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0$ | 0 | 0 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; CCa, cholangiocarcinoma; CD, Crohn's disease; CF, cystic fibrosis; f, females; HS, healthy subjects; IQR, interquartile range; LTx, liver transplantation; n, number; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC ulcerative colitis.

Related to 136 patients with PSC.

Comparison of the prevalence in all patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis with control groups:

p < 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Comparison of the prevalence in all patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis with control groups:

p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test for dichotomous values.

Comparison of the prevalence within the cohorts of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis:

Debrecen vs. Berlin, Hamburg and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis test).

Hamburg vs. Berlin, Debrecen and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

Berlin vs. Hamburg (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

London vs. Hamburg and Debrecen, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

Berlin vs. Hamburg and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

Hamburg vs. Berlin and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

Debrecen vs. Berlin and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

London vs. Berlin (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

Debrecen vs. Berlin and London, respectively (p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test).

In total, 145 gender-matched controls were enrolled in this study comprising 95 patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and 50 healthy subjects (HS). The patients with CF, a multi-systemic disorder with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and biliary cirrhosis with a different pathogenesis, were included as disease controls with regard to PSC. The 50 apparently healthy subjects (HS) with no liver or intestinal pathology were both age- and gender-matched.

The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki 1989).

Generation of GP2-expressing cell lines

Stable HEp-2 cell lines expressing membrane GPI-anchored GP2 isoforms were generated through transduction with lentiviruses. Briefly, coding sequences of GP2 isoforms sequences were amplified with PCR and cloned into pLVX-IRES-puro plasmids each using T4 DNA ligase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. To confirm successful cloning, plasmids were Sanger sequenced. For transduction, lentiviruses were produced using the Lenti-X Lentiviral Expression System (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, USA). Thus, an 80% confluent Lenti-X 293T cell line was co-transfected with the six plasmids containing GP2 isoforms or an “empty” vector. The harvested supernatants were concentrated by centrifugation in Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and employed for transduction of HEp-2 cells. Selection of successfully transduced cells was performed by adding the antibiotic puromycin to cell culture.

Confirmation of GP2 transduction into HEp-2 cells was done with reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT qPCR). In brief, RNA from transduced cells was isolated with RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). After RT reaction using Maxima First Strand Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), qPCR was performed in the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany) with following primers: 5- ATCAACGTGATTCCACCATCC-3 and 5- TTGAGCAAGAAGGCTGGC-3 (for GP2 gene); 5-AAATGTTTCATTGTGGGAGC-3 and 5- ATATGAGGCAGCAGTTTCTC-3 (for RPLP0 gene). RPLP0 was used as reference gene. Obtained PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis.

Expression of GP2 isoform proteins was confirmed by Western blotting. Briefly, transduced HEp-2 cells were lysed and the lysate run on SDS-PAGE. Separated bands transferred on the blotting membrane were developed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to GP2 reactive with all isoforms (GA Generic Assays, Dahlewitz, Germany). Isoforms of GP2 were revealed by a secondary anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with horse radish peroxidase employing enhanced chemiluminescence.

Membrane expression of GPI-anchored GP2 isoforms was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis.

Detection of IgG and IgA to GP2 isoforms

IgG and IgA to GP2 isoforms were determined by IFA employing stably transduced HEp-2 cells expressing membrane GPI-anchored GP2 isoforms 1-4. Briefly, cells were fixed on glass slides as described elsewhere (30) and incubated with 1 in 20 diluted sera for 1 h at room temperature. HEp-2 cells transduced with an empty vector were used as negative control. After washing, bound autoAbs to GP2 isoforms were revealed by incubation of polyclonal anti-human IgG or IgA antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Agilent, Santa Clar, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. A fluorescent microscope (Axiovert 40, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) was used to read specific staining of HEp-2 cells. Brighter fluorescent staining of the cellular membrane of transduced HEp-2 cells in comparison with HEp-2 cells transduced with an empty vector was scored positive.

Statistical methods

Data were tested for normality by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov-test and non-normally distributed data were reported by median and quartile ranges. The two-tailed, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test for statistically significant differences of independent samples in 2 and more groups, respectively. Prevalence comparison between groups was performed by two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Logistic regression analysis was employed to test for the influence of explanatory (independent) variables on a binomial response variable and to detect possible clinical confounders on such association (age, gender, concomitant IBD, concomitant overlap with AIH) by a backward exclusion strategy resulting in adjusted odds ratios. P < 0.05 was considered as significant. MedCalc software version 12.7.0.0 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used for performing statistical analysis.

Results

Detection of autoantibodies to GP2 isoforms by indirect immunofluorescence

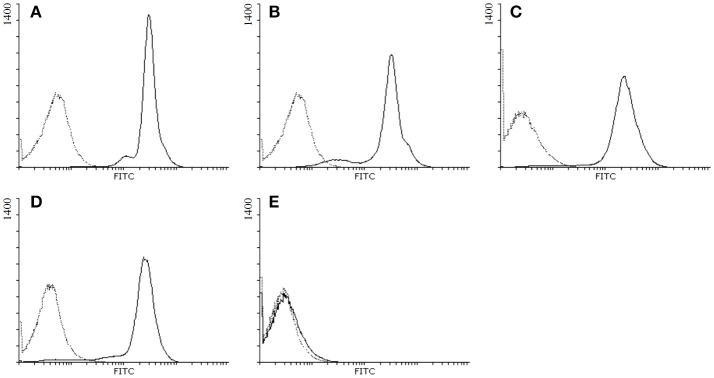

GP2 isoforms were expressed stably in HEp-2 cells as GPI-anchored molecules in the membrane of these cells by lentiviruses transduction. As control, one cell line was transduced with an empty vector only. The presence of membrane-bound GP21 to GP24 in the respective lines and their absence in the empty vector cell line was confirmed by FACS analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Detection of the membrane expression of GP2 isoforms in HEp-2 cells by flow cytometry. GP2 expressed in HEp-2 cells was stained with polyclonal antibodies raised against full length human GP2 followed by FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG: (A) HEp-2 cells expressing human GP2 isoform 1; (B) GP2 isoform 2; (C) GP2 isoform 3; (D) GP2 isoform 4; (E) HEp-2 cells transduced with an empty vector; black solid lines: primary and secondary antibody staining; black dotted lines: secondary antibody staining only.

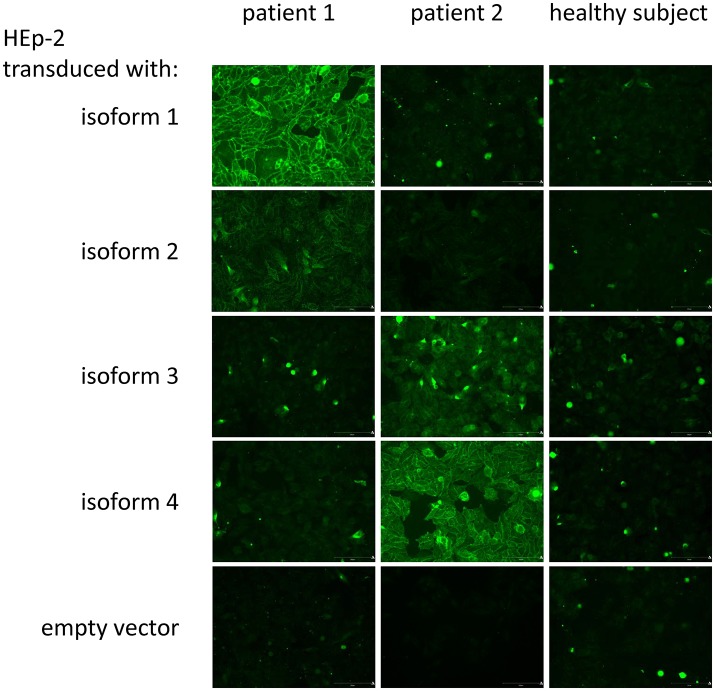

For the detection of aGP21 to aGP24 by IFA, cells of each line were fixed to conventional glass slides and used as targets for specific autoAb analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay for the detection of IgA to GP2 isoforms: Exemplarily, two patient sera and one serum of a healthy subject as control were run on HEp-2 cells transduced with GP2 isoforms 1 (GP21) to 4 (GP24) with glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor and an empty vector, respectively. Patient 1 demonstrated a strong specific binding to membrane-bound GP21 and a weak one to GP22, whereas patient 2 showed the typical binding pattern for a strong positive binding to GP24 and a weak one for GP23. The healthy subject did not reveal a positive membrane-reactive pattern on the respective transduced HEp-2 cells.

Occurrence of IgA and IgG to GP2 isoforms in patients and controls

IgA and IgG against GP21−4 were determined in 212 patients with PSC of four European hospitals and 145 gender-matched controls. Of note, the 50 HS included as controls were gender- as well as aged-matched to all PSC patients (Table 1). Patients with PSC of the Debrecen cohort were significantly younger compared to the remaining three PSC cohorts whereas the Hamburg cohort had a significantly higher median age (p < 0.05, respectively).

Apart from aGP23, all other aGP2 demonstrated significantly elevated prevalences in PSC patients compared with controls including HS and patients with CF (p < 0.05, respectively) (Table 2). However, this did not hold true for all PSC cohorts of the four different centers.

Table 2.

Frequency of IgA and IgG against GP2 isoforms 1 (aGP21) to 4 (aGP24) detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay on stabile isoform-transduced HEp2 cells in 212 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) from different hospitals and 145 controls.

| aGP21 | aGP22 | aGP23 | aGP24 | aGP21/2/3/4 | aGP21/4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | IgA (%) | IgG (%) | IgA (%) | IgG (%) | IgA (%) | IgG (%) | IgA (%) | IgG (%) | IgA (%) | IgG (%) | IgA and/ or IgG (%) | IgA (%) | |

| PSC | 212 | 100 (47.2)** | 92 (43.4)** | 21 (9.9)* | 40 (18.9)* | 10 (4.7) | 31 (14.6) | 103 (48.6)** | 81 (38.2)** | 140 (66.0)** | 119 (56.1)** | 154 (72.6)** | 140 (66.0)** |

| Berlin | 23 | 6 (26.1)** | 7 (30.4)* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (13.0)* | 2 (8.7) | 8 (34.8)** | 8 (34.8) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (34.8)** |

| Hamburg | 30 | 11 (36.7)** | 12 (40.0)* | 5 (16.7)* | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 9 (30.0)** | 8 (26.7)* | 16 (53.3)** | 16 (53.3)* | 17 (56.7)* | 16 (53.3)** |

| London | 83 | 42 (50.6)** | 39 (47.0)** | 2 (2.4) | 28 (33.7)** | 4 (4.8) | 26 (31.3)* | 52 (62.7)** | 40 (48.2)** | 59 (71.1)** | 50 (60.2)** | 68 (81.9)** | 59 (71.1)** |

| Debrecen | 76 | 41 (53.9)** | 34 (44.7)** | 14 (18.4)** | 11 (14.5) | 5 (6.6) | 4 (5.3) | 39 (51.3)** | 31 (40.8)** | 57 (75.0)** | 45 (59.2)** | 59 (77.6)** | 57 (75.0)** |

| Controls | 145 | 2 (1.4) | 11 (7.6) | 1 (0.7) | 12 (8.3) | 4 (2.8) | 20 (13.8) | 1 (0.7) | 11 (7.6) | 6 (4.1) | 33 (22.8) | 34 (23.4) | 3 (2.1) |

| CF | 95 | 1 (1.1) | 8 (8.4) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (9.5) | 4 (4.2) | 18 (18.9)$ | 1 (1.1) | 9 (9.5) | 5 (5.3) | 26 (27.4)$ | 26 (27.4) | 2 (2.1) |

| HS | 50 | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.0) | 0 | 3 (6.0) | 0 | 2 (4.0) | 0 | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (14.0) | 8 (16.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| YI (PSC vs. controls) | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.64 | |

CF, cystic fibrosis, f, females; HS, healthy subjects; IQR, interquartile range; n, number; YI, Youden index (specificity+sensitivity-1)

Comparison of the prevalence of positive aGP2 in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis with controls (n = 145):

p < 0.05,

p < 0.0001, by Fisher's exact test, respectively.

Comparison of the prevalence of positive aGP2 in patients with cystic fibrosis with healthy subjects (n = 50):

p < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test.

Regarding IgA reactivity, aGP21 (47.2%) and aGP24 positivity (48.6%) revealed the highest frequencies in PSC patients resulting in an even significantly elevated combined positive rate of 66.0% (aGP21and/or4 IgA) compared with both rates of single aGP2 isoform IgA testing (p < 0.0001, = 0.0004, respectively). Analysis of all four aGP2 isoform IgA did not increase the positive rate further. Apart from aGP23 IgA, all other aGP2 isoform IgA demonstrated significantly lower prevalences in controls. Thus, aGP21and/or4 IgA testing revealed the best Youden index (YI) of 0.64 being a measure of assay performance.

In terms of IgG, aGP21, and aGP24 testing revealed the highest positive rates in PSC patients, too. However, their prevalences were lower in contrast to the corresponding IgA, but only the difference for aGP24 reached significance (p = 0.0395). Further, both aGP2 isoform IgG had significantly more positives in the control groups (p < 0.5, respectively). That resulted in halved YIs for both and, thus, demonstrated a poorer assay performance for the discrimination of patients with PSC from controls in comparison to corresponding IgA analysis.

Association of IgA and IgG to GP2 isoforms with PSC phenotypes

The possible association of the presence of IgA and IgG to GP21−4 in PSC patients with performed liver transplantation (LTx) and concomitant occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis, cirrhosis; cholangiocarcinoma, CD, UC, IBD (CD or UC) was investigated by Fisher's exact test (Table 3). Further, established associations were investigated by logistic regression analysis to analyze the influence of confounding factors.

Table 3.

Positive and negative (italic) significant associations of IgA and IgG against GP2 isoforms 1 (aGP21) to 4 (aGP24) with the clinical phenotype in 212 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) by Fisher's exact test.

| N | IBD | CD | UC | AIH | Cirrhosis | CCa | LTx | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC | 212 |

aGP21/4 IgA p = 0.01386 aGP21/2/3/4 IgA p = 0.0076 |

aGP24 IgA p = 0.0051 aGP21/4 IgA p = 0.0056 aGP22 IgG p = 0.0199 aGP24 IgG p = 0.0447 |

aGP23 IgG p < 0.0001 |

aGP22 IgA p = 0.0006 |

|||

| Berlin | 23 | |||||||

| Hamburg | 30 |

aGP22 IgA p = 0.0472 |

||||||

| London | 83 |

aGP23 IgG p = 0.0288 |

aGP24 IgA p = 0.0055 aGP21/2/3/4 IgA p = 0.0144 |

aGP23 IgG p = 0.0316 |

||||

| Debrecen | 76 | aGP22 IgA p = 0.0261 aGP22 IgG p = 0.0349 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; CCa, cholangiocarcinoma; CD, Crohn's disease; LTx, liver transplantation; n, number; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC ulcerative colitis.

Association of IgA and IgG to GP2 isoforms with cirrhosis

A significantly positive association of aGP2 isoform IgA and IgG positivity in PSC was established for the concomitant occurrence of cirrhosis. Thus, aGP21 and aGP24 IgA as well as aGP22 and aGP24 IgG were more prevalent in PSC patients with cirrhosis than in those without (p < 0.05, respectively). Similar positive associations could be found in the larger cohorts from London and Debrecen, too. Logistic regression analysis for the risk analysis of the occurrence of cirrhosis in all 212 PSC patients confirmed aGP21 and aGP24 IgA as independent predictors in older male PSC patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of independent variables for the risk prediction of liver transplantation (LTx) and the occurrence of cirrhosis in 212 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Coefficient | SE | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cirrhosis | aGP21 IgA | 0.3243 | 0.1514 | 1.3831 | 1.0279–1.8609 | 0.0322 |

| aGP24 IgA | 0.1729 | 0.1771 | 1.5178 | 1.0727–2.1478 | 0.0185 | |

| age | 0.0273 | 0.0100 | 1.0277 | 1.0077–1.0480 | 0.0063 | |

| gender | −0.6693 | 0.3235 | 0.5121 | 0.2716–0.9654 | 0.0385 | |

| LTx | aGP22 IgA | −3.02104 | 1.27092 | 0.0488 | 0.0040–0.5886 | 0.0175 |

| cirrhosis | 3.70772 | 0.49727 | 40.7608 | 15.3800–108.0262 | < 0.0001 | |

| AIH overlap | −2.63423 | 1.00286 | 0.0718 | 0.0101–0.5124 | 0.0086 | |

| UC | 1.82313 | 0.49012 | 6.1912 | 2.3691–16.1799 | 0.0002 |

The presence of IgA and IgG to GP2 isoforms 1 (aGP21) to 4 (aGP24) and the concomitant occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), and autoimmune hepatitis overlap as well as age and gender were used as possible predictive independent variables for the logistic regression analysis.

CI, confidence interval, OR, adjusted odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Association of aGP22 IgG with PSC patients without LTx

A significantly negative association of aGP22 IgA was revealed for LTx performed in PSC patients of all cohorts. This significantly more prevalent aGP22 IgA occurrence in PSC patients without LTx was not detected in the single PSC cohorts but confirmed by logistic regression analysis as independent predictor in PCS patients without LTx demonstrating concomitant cirrhosis, UC and no AIH overlap (Table 4).

Association of IgA and IgG to GP2 isoforms with IBD

Patients with PSC and concomitant CD demonstrated a significantly lower prevalence of aGP21/4 and aGP21/2/3/4 IgA. However, this association was neither found in the single PSC cohorts nor confirmed by logistic regression analysis. There was no further association of all PSC patients with and without IBD, UC or CD regarding the concomitant presence of aGP2 isoform autoAbs by Fisher's exact test. Only the London cohort demonstrated significantly less frequent aGP23 IgG in PSC patients with concomitant IBD and the Hamburg cohort significantly less frequent aGP22 IgA in patients with UC (p < 0.05, respectively) (Table 3).

Logistic regression analysis revealed the concomitant occurrence of UC as an independent risk factor for liver transplantation along with cirrhosis. The presence of GP22 IgA and AIH overlap were negative predictors in this regard (Table 4).

Discussion

The recent reports of the occurrence of aGP2 IgA in patients with large biliary duct disorders including PSC and of aGP2 IgA as marker of severe disease, as well as cholangiocarcinoma ushered in a new era in PSC serology (7, 31). Until recently, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) have been considered as main serological marker of PSC (32) and particularly ANCA IgA has been associated with cirrhosis linked to intestinal infections (33). However, attempts to identify the respective autoantigenic ANCA as well as other PSC-specific targets have been inconclusive so far (34). Conversely, IgG to proteinase 3 (PR3) being a cytoplasmic ANCA target could be detected by highly sensitive enzyme immunoassays or microbead-based immunoassays in up to 44% of patients with PSC (35, 36). Thus, apart from the neutrophilic target PR3, GP2 was identified as an autoantigenic target in PSC and questions on a possible pathogenic role of respective specific IgA being the mucosal immunoglobulin in contrast to IgG were raised. Since four GP2 isoforms were discovered and specific IgG and IgA against them were described in patients with IBD (24–26, 37), this study attempted to ascertain the frequency of IgG and IgA to GP2 isoforms in PSC and their possible relation to the PSC phenotype as stratification factor in PSC.

In contrast to recent reports demonstrating preferentially aGP2 IgA in PSC (7, 8), this study revealed both IgA as well as IgG against GP2 isoforms.

The IgG to GP2 isoforms determined in this study demonstrated both lower sensitivities and specificities in contrast to IgA against the corresponding GP2 isoforms which resulted in poorer assay performances of the former. Of note, apart from significantly higher positive rates of IgG to GP2 isoforms in PSC, we detected a significantly elevated prevalence of IgG GP23Ab in control patients with CF (18.9%) vs. healthy controls (4.0%). This finding warrants further investigation and could indicate a different loss of tolerance to GP2 isoforms in CF.

In terms of discrimination of PSC from controls, aGP21 IgA (47.2%) and aGP24 IgA-positives (48.6%) revealed the highest frequencies amongst all aGP2. Interestingly, combination of both led to a significantly elevated sensitivity of 66.0%. This was a significantly higher prevalence than the corresponding total prevalence reported by Jendrek et al. (66.0 vs. 48.7%, p < 0.0001). Thus, combined testing of both aGP21 and aGP24 IgA appears more sensitive than the determination of IgA to just one GP2 isoform. Indeed, the single positivity rates of aGP21 and aGP24 IgA in this study were not significantly different from the rate reported elsewhere. Further, due to the higher specificity, combined aGP21 and GP24 IgA testing demonstrated the best diagnostic performance for PSC by a YI of 0.64 regarding the analysis of all aGP2 and combinations thereof.

As GP21 and GP24 represent long (537 amino acids) and short GP2 isoforms (387 amino acids), respectively, they could bear differing epitopes (24). Remarkably, GP22 and GP23 which differ from GP21 and GP24 in just three amino acids (valine-proline-arginine), respectively (25), demonstrated significantly diminished IgA binding in PSC. This adds support to the notion that GP2 isoforms bear different autoantigenic epitopes, all of which should be contained in GP2-antigenic preparations in aGP2 immunoassays for proper and accurate autoAb testing.

IgG and in particular IgA against GP2 isoforms revealed different associations with the PSC phenotype. In fact, aGP21 and aGP24 IgA were demonstrated as positive predictors of cirrhosis in older males with PSC. The cirrhosis in PSC is mainly characterized by extensive fibrosis around the larger bile ducts (4). An association of aGP2 IgG and IgA detected by ELISA with the stenosing/stricturing phenotype in patients with CD, which is characterized by fibrostenotic changes either, was established in one longitudinal and several cross-sectional studies (18). Further, the need for surgical resection and repeated surgical intervention in CD was associated with the occurrence of aGP2 (20, 22). Wölfel et al. demonstrated a significant association of aGP21 IgA and a tendency for′ GP24 IgA with earlier surgical recurrence in CD (20). Further, aGP21 and aGP22 IgA were reported to be significantly associated with the stenosing/stricturing and severity of disease but not with disease activity. Thus, IgA against GP2 isoforms might be a serological marker for the development of fibrostenotic changes in both the gut and larger bile ducts.

There is clearly a need for risk stratification in PSC (5, 38) and aGP2 IgA could be of prognostic value like autoAbs to gp210 do in primary biliary cholangitis (39). Given a potential ascending pathophysiology of PSC, aGP21/4 IgA could be a stage-defining biomarker (40). This is of interest, as aGP2 IgA secreted onto mucosal surfaces might mediate the up-take of GP2-covered bacteria by GP2-bearing M cells of the intestinal follicle-associated epithelium (15, 41) and, thus, partake in the development of severe complications or even pre-tumor stages. Patients with PSC appear to demonstrate a gut microbial signature distinct from both normal individuals and patients with UC without liver disease whereas their microbial signature is not dependent on the occurrence of IBD (42). Thus, fecal microbiota profiles can be used as markers of PSC (43). Altogether, that hints at an involvement of the microbiota in the pathophysiology of PSC which was demonstrated in a well-established mouse models for PSC and spontaneous bile duct inflammation (44, 45).

Interestingly, CD appears to confer prognostic favor in PSC and a lower risk to develop adverse effects (1). Thus, it remains to be determined in prospective studies whether aGP2-positive CD patients characterized by complicated CD with fibrotic adverse effects also demonstrate severe PSC.

All 5 PSC patients with cholangiocarcinoma demonstrated aGP21 and/or aGP24 IgA. This might be a hint that aGP2 IgA occurs earlier in the disease course and that the tolerance break is linked with the mucosal microbiota interaction of GP2. In this context, the elevation of aGP23 IgG in patients with CF is of interest since approximately 30% of patients with CF have clinically significant liver disease (46).

The finding that aGP21/4 and aGP21/2/3/4 IgA demonstrated significantly lower prevalences in PSC patients with CD was surprising. We speculate that PSC with concomitant CD might be different from CD without obvious liver involvement regarding the loss of tolerance to GP2. However, this notion needs to be treated with caution since it could be confirmed neither in the single cohorts nor by logistic regression analysis.

As most multi-center studies of this kind, our study lacks perfection. The controls were not age matched to patients with PSC due to the younger age of the controls with CF. Further, there was a high level of diversity in the distinct PSC cohorts of the four European hospitals regarding number of patients and their phenotype. The established independent predictors of cirrhosis aGP21 and aGP24 IgA could not be associated in all single cohorts with the concomitant occurrence of cirrhosis.

Altogether, combined aGP21 and aGP24 analysis is required for sensitive PSC-specific autoAb testing and should be preferred to the autoAb analysis against single aGP2 isoforms only. aGP21 and aGP24 IgA might be predictors of cirrhosis in PSC and, thus, an useful alternative for risk prediction. Elevated aGP2 IgA may demonstrate a link to fibrotic changes observed in IBD in particular in CD. Prospective studies including patients tested pre- and post-liver transplantation will provide excellent hints regarding the pathophysiological role of these autoAbs.

Author contributions

DR and PS conceived of the study and participated in its design and data evaluation. RK and JS conducted the transduction experiments and participated in the development of the indirect fluorescence assay. MS participated in the development of the indirect fluorescence assay and carried out the assays. MP, TT, DCB, JP, MM, DB, JH, ML, KC, AF, and CS recruited patients, provided patient data and participated in the statistical evaluation thereof. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

DR is a shareholder and employee of GA Generic Assays GmbH and Medipan GmbH. MS receives a grant from GA Generic Assays GmbH. Both have no further personal or professional interests to declare.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GP2

zymogen glycoprotein 2

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- GP21

GP2 isoform 1

- IFA

indirect immunofluorescence assay

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- CD

Crohn's disease

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- autoAb

autoantibody

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- HS

healthy subjects

- IQR

interquartile range

- LTx

liver transplantation

- YI

Youden index

Footnotes

Funding. AF received infrastructure support from the DFG Excellence Cluster 306 Inflammation at Interfaces. CS was supported by the Helmut and Hannelore Greve Foundation and the YAEL Foundation. Both AF and CS were supported by the DFG (KFO306). PS and RK received support from the DFG (grant number 288074052, SHI 1147/3-1) and the BMBF InnoProfile-Transfer 03IPT611X. MP was supported by the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (BO/00232/17/5) and Research Grants of National Research Development and Innovation Office (K115818/2015/1).

References

- 1.Weismuller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY, et al. Patient age, sex, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotype associate with course of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology (2017) 152:1975–84. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb GJ, Hirschfield GM. Using GWAS to identify genetic predisposition in hepatic autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. (2016) 66:25–39. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. (2012) 56:1181–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. (2017) 67:1298–323. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vesterhus M, Holm A, Hov JR, Nygard S, Schrumpf E, Melum E, et al. Novel serum and bile protein markers predict primary sclerosing cholangitis disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. (2017) 66:1214–22. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowlus CL, Olson KA, Gershwin ME. Evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) 14:749. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jendrek ST, Gotthardt D, Nitzsche T, Widmann L, Korf T, Michaels MA, et al. Anti-GP2 IgA autoantibodies are associated with poor survival and cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut (2017) 66:137–44. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tornai T, Tornai D, Sipeki N, Tornai I, Alsulaimani R, Fechner K, et al. Loss of tolerance to gut immunity protein, glycoprotein 2 (GP2) is associated with progressive disease course in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:399. 10.1038/s41598-017-18622-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu S, Lowe AW. The pancreatic zymogen granule membrane protein, GP2, binds Escherichia coli Type 1 fimbriae. BMC Gastroenterol. (2009) 9:58. 10.1186/1471-230X-9-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schierack P, Rodiger S, Kolenda R, Hiemann R, Berger E, Grzymajlo K, et al. Species-specific and pathotype-specific binding of bacteria to zymogen granule membrane glycoprotein 2 (GP2). Gut (2015) 64:517–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner L, Paclik D, Fritz C, Reinhold D, Roggenbuck D, Sturm A. Identification of pancreatic Glycoprotein 2 as an endogenous immunomodulator of innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. (2012) 189:2774–83. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Schierack P, Bogdanos DP, Conrad K, Laass MW. Crohn's disease specific pancreatic antibodies: clinical and pathophysiological challenges. Clin Chem Lab Med. (2014) 52:483–94. 10.1515/cclm-2013-0801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roggenbuck D, Hausdorf G, Martinez-Gamboa L, Reinhold D, Buttner T, Jungblut PR, et al. Identification of GP2, the major zymogen granule membrane glycoprotein, as the autoantigen of pancreatic antibodies in Crohn's disease. Gut (2009) 58:1620–8. 10.1136/gut.2008.162495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komorowski L, Teegen B, Probst C, Aulinger-Stocker K, Sina C, Fellermann K, et al. Autoantibodies against exocrine pancreas in Crohn's disease are directed against two antigens: the glycoproteins CUZD1 and GP2. J Crohns Colitis (2013) 7:780–90. 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hase K, Kawano K, Nochi T, Pontes GS, Fukuda S, Ebisawa M, et al. Uptake through glycoprotein 2 of FimH(+) bacteria by M cells initiates mucosal immune response. Nature (2009) 462:226–30. 10.1038/nature08529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Sun K, Wu Y, Yang Y, Tso P, Wu Z. Interactions between intestinal microbiota and host immune response in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:942. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basson A, Trotter A, Rodriguez-Palacios A, Cominelli F. Mucosal interactions between genetics, diet, and microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:290. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Baumgart DC, Schierack P, Conrad K, Laass MW. Autoimmunity in crohn's disease-a putative stratification factor of the clinical phenotype. Adv Clin Chem. (2016) 77:77–101. 10.1016/bs.acc.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roggenbuck D, Humbel RL, Reinhold D, Bogdanos DP, Conrad K, Laass MW. Glycoprotein 2 antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease - no association with disease phenotype? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2012) 56:e5. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318275fa77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wölfel G, Lopez R, Hösl J, Kunst C, Roggenbuck D, Mueller M, et al. The novel isoforms 1 and 4 of serum anti-GP2 antibody are linked to earlier surgical recurrence in Crohn's disease (CD) subjects after first surgery. Gastroenterology (2017) 152(5 Suppl. 1):S368–9. 10.1016/S0016-5085(17)31481-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner L, Sturm A, Roggenbuck D, Yahav L, Zion T, Meirowithz E, et al. Antibodies against glycoprotein 2 are novel markers of intestinal inflammation in patients with an ileal pouch. J Crohns Colitis (2013) 7:e522–32. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degenhardt F, Dirmeier A, Lopez R, Lang S, Kunst C, Roggenbuck D, et al. Serologic anti-GP2 antibodies are associated with genetic polymorphisms, fibrostenosis, and need for surgical resection in crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2016) 22:2648–57. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunder AK, Hov JR, Borthne A, Gleditsch J, Johannesen G, Tveit K, et al. Prevalence of sclerosing cholangitis detected by magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with long-term inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology (2016) 151:660–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuoka S. Molecular cloning and sequences of cDNAs encoding alpha (large) and beta (small) isoforms of human pancreatic zymogen granule membrane-associated protein GP2. Biochim Biophys Acta (2000) 1491:376–80. 10.1016/S0167-4781(00)00057-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Röber N, Noss L, Goihl A, Reinhold D, Jahn J, Zimmer KP, et al. Autoantibodies against GP2 isoforms in pediatric patients with Crohn's disease: differences in reactivity and correlation to clinical features. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2017) 23:1624–36. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roggenbuck D, Rober N, Bogdanos DP, Goihl A, Reinhold D, Conrad K, et al. Autoreactivity to isoforms of glycoprotein 2 in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chim Acta (2015) 442:82–3. 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, Nagorney DM, Boberg KM, Shneider B, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology (2010) 51:660–78. 10.1002/hep.23294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrad K, Roggenbuck D, Laass MW. Diagnosis and classification of ulcerative colitis. Autoimmun Rev. (2014) 13:463–6. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laass MW, Roggenbuck D, Conrad K. Diagnosis and classification of Crohn's disease. Autoimmun Rev. (2014) 13:467–71. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George S, Paulick S, Knutter I, Rober N, Hiemann R, Roggenbuck D, et al. Stable expression of human muscle-specific kinase in HEp-2 M4 cells for automatic immunofluorescence diagnostics of myasthenia gravis. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e83924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papp M, Sipeki N, Tornai T, Altorjay I, Norman GL, Shums Z, et al. Rediscovery of the anti-pancreatic antibodies and evaluation of their prognostic value in a prospective clinical cohort of crohn's patients: the importance of specific target antigens [GP2 and CUZD1]. J Crohns Colitis (2015) 9:659–68. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilschanski M, Chait P, Wade JA, Davis L, Corey M, St LP, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in 32 children: clinical, laboratory, and radiographic features, with survival analysis. Hepatology (1995) 22:1415–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papp M, Sipeki N, Vitalis Z, Tornai T, Altorjay I, Tornai I, et al. High prevalence of IgA class anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) is associated with increased risk of bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. (2013) 59:457–66. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung BK, Guevel BT, Reynolds GM, Gupta Udatha DB, Henriksen EK, Stamataki Z, et al. Phenotyping and auto-antibody production by liver-infiltrating B cells in primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cholangitis. J Autoimmun. (2017) 77:45–54. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sowa M, Grossmann K, Knutter I, Hiemann R, Rober N, Anderer U, et al. Simultaneous automated screening and confirmatory testing for vasculitis-specific ANCA. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e107743. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stinton LM, Bentow C, Mahler M, Norman GL, Eksteen B, Mason AL, et al. PR3-ANCA: a promising biomarker in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e112877. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S, Luo J, Wu Z, Roggenbuck D, Schierack P, Reinhold D, et al. Antibodies against glycoprotein 2 display diagnostic advantages over ASCA in distinguishing CD from intestinal tuberculosis and intestinal Behcet's disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. (2018) 9:e133. 10.1038/ctg.2018.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trivedi PJ, Corpechot C, Pares A, Hirschfield GM. Risk stratification in autoimmune cholestatic liver diseases: opportunities for clinicians and trialists. Hepatology (2016) 63:644–59. 10.1002/hep.28128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura M, Kondo H, Mori T, Komori A, Matsuyama M, Ito M, et al. Anti-gp210 and anti-centromere antibodies are different risk factors for the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology (2007) 45:118–27. 10.1002/hep.21472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansen PL, Ghallab A, Vartak N, Reif R, Schaap FG, Hampe J, et al. The ascending pathophysiology of cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology (2017) 65:722–38. 10.1002/hep.28965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Werner L, Schierack P, Bogdanos DP, Conrad K. Glycoprotein 2 antibodies in Crohn's disease. Adv Clin Chem. (2013) 60:187–208. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407681-5.00006-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kummen M, Holm K, Anmarkrud JA, Nygard S, Vesterhus M, Hoivik ML, et al. The gut microbial profile in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis is distinct from patients with ulcerative colitis without biliary disease and healthy controls. Gut (2016) 66:611–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruhlemann MC, Heinsen FA, Zenouzi R, Lieb W, Franke A, Schramm C. Faecal microbiota profiles as diagnostic biomarkers in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut (2017) 66:753–4. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabibian JH, O'Hara SP, Trussoni CE, Tietz PS, Splinter PL, Mounajjed T, et al. Absence of the intestinal microbiota exacerbates hepatobiliary disease in a murine model of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology (2016) 63:185–96. 10.1002/hep.27927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schrumpf E, Kummen M, Valestrand L, Greiner TU, Holm K, Arulampalam V, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to a mouse model of spontaneous bile duct inflammation. J Hepatol. (2017) 66:382–89. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moyer K, Balistreri W. Hepatobiliary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2009) 25:272–8. 10.1097/MOG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]