Abstract

Transepithelial Cl- and HCO3- transport is crucial for the function of all epithelia, and HCO3- is a biological buffer that maintains acid-base homeostasis. In most epithelia, a series of Cl-/HCO3- exchangers and Cl- channels that mediate Cl- absorption and HCO3- secretion have been detected in the luminal and basolateral membranes. Slc26a9 belongs to the solute carrier 26 (Slc26) family of anion transporters expressed in the epithelia of multiple organs. This review summarizes the expression pattern and functional diversity of Slc26a9 in different systems based on all investigations performed thus far. Furthermore, the physical and functional interactions between Slc26a9 and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) are discussed due to their overlapping expression pattern in multiple organs. Finally, we focus on the relationship between slc26a9 mutations and disease onset. An understanding of the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of Slc26a9 in multiple organs offers new possibilities for disease therapy.

Keywords: Slc26a9, multiple organs, expression pattern, physiological function, pathophysiology, health and disease

Introduction

Acid/base homeostasis is vital for life because protein and enzyme functions, cell structures and membrane permeability are altered by changing pH. In most epithelia, transepithelial chloride absorption and bicarbonate secretion are associated with fluid secretion, which is important for normal functioning. Slc26 anion exchangers are members of a recently discovered gene family with multifunctional transmembrane proteins. These proteins mediate the transport of various monovalent and divalent anions, including chloride, bicarbonate, sulfate, iodide and oxalate, mainly across the plasma membrane of epithelial cells and contribute to the composition and pH of secreted fluids in the body (El Khouri and Toure, 2014). This gene family consists of 11 members and is divided into three groups, e.g., selective sulfate transporters, Cl-/HCO3- exchangers and anion channels, based on their proven or putative transport properties (Mount and Romero, 2004; Dorwart et al., 2008; Ohana et al., 2009; Alper and Sharma, 2013). Slc26a9 is classified into the third group and expressed in the apical membrane of multiple organs to regulate Cl- and HCO3- transport by different ion transport methods. In this review, we discuss the current knowledge of the expression pattern, functional diversity, regulatory mechanism and pathophysiology of this novel protein in different organs.

Cloning, Expression and Physiological Functions of Slc26a9 in Different Organs

Slc26a9 (solute carrier family 26 member 9) is a member of the Slc26 family of multifunctional anion transporters. Slc26a9 was cloned on the basis of its homology to other Slc26 isoforms. In humans, SLC26A9 maps to chromosome 1 and encodes a 791-amino-acid protein (Lohi et al., 2002). SLC26A9 (human)/Slc26a9 (mouse) is expressed at high levels in the lung (Lohi et al., 2002) and stomach (Xu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2015), to some extent in the proximal duodenum, and at low levels in the distal duodenum and pancreas (Liu et al., 2015). Slc26a9 is also detected in some specialized cells in the kidney (Amlal et al., 2013), neural system (Chang et al., 2009b), reproductive tract (Dorwart et al., 2007), salivary gland (Tandon et al., 2017), and prostate (Lohi et al., 2002). Although Slc26a9 is not expressed in normal enamel cells (Lacruz et al., 2012), it is upregulated in Slc26a1 and Slc26a7 null mice, suggesting that it plays a strong compensatory role during enamel maturation (Yin et al., 2015). Functional studies showed that Slc26a9 is involved in diverse transport modes in different systems. First, recent work in Xenopus oocytes, Fischer rat thyroid epithelial cells, HEK cells and COS-7 cells expressing Slc26a9 has shown that Slc26a9 is a highly selective Cl- channel with minimal OH/HCO3 permeability that is regulated by with-no-lysine kinases (WNK) and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in heterologous cells (Dorwart et al., 2007; Loriol et al., 2008; Bertrand et al., 2009; Salomon et al., 2016). Loriol et al. reported that the conductivity of Slc26a9 is enhanced at high HCO3- concentrations (Loriol et al., 2008). Second, electrophysiological experiments involving Xenopus oocytes, HEK cells, and animal models have attributed the following three different transport modes to Slc26a9: Cl- channel (Loriol et al., 2008; Bertrand et al., 2009; Avella et al., 2011; Ousingsawat et al., 2012; Amlal et al., 2013), Cl-/HCO3- exchanger (Xu et al., 2005; Demitrack et al., 2010) and Na+ transporter (Chang et al., 2009b). Additionally, the Slc26a9 protein plays multiple physiological roles in the transport of several anions, including I-, NO3, gluconate, SO42-, and Br-, at different conductances (Dorwart et al., 2007; Loriol et al., 2008).

Slc26a9 Functions as a Cl- Channel in the Airway

Slc26a9 is predominantly expressed in the apical membrane of alveolar, tracheal, and bronchiolar epithelial cells in the lung (Lohi et al., 2002; Bertrand et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014). Initial studies have shown that Slc26a9 contributes to constitutive and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent Cl- secretion in cultured human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells, and Slc26a9 has been suggested to functionally interact with CFTR in vitro (Bertrand et al., 2009; Avella et al., 2011), indicating that Slc26a9 may serve as a chloride channel that compensates for CFTR dysfunction in CF. Based on the functional properties of Slc26a9 in transduced cells and its expression pattern in human and mouse airways (Lohi et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2009b), questions regarding the function of Slc26a9 in maintaining airway surface liquid (ASL) homeostasis in health and allergic airway disease have emerged. Studies investigating the function of Slc26a9 in native epithelia have been performed in the lung of Slc26a9 null mice, and the essential role of Slc26a9 in mediating Cl- secretion and preventing mucus obstruction during airway inflammation induced by IL-13 instillation (Anagnostopoulou et al., 2012), but not under physiological conditions, has been identified. This finding suggests that anion conductance, which was found to be upregulated in allergic airway inflammation in a previous study (Anagnostopoulou et al., 2010), may indeed occur through Slc26a9 and that the inability to activate this conductance may result in an increase in airway pathology. Taken together, these data indicate that besides TMEM16A and CFTR, Slc26a9 functions as an alternative chloride channel that may contribute to the regulation of ASL, which is essential for mucus clearance under pathophysiological conditions in the airways.

Slc26a9 Is Involved in Various Ion Transport Systems in the Digestive System

In the Stomach

Slc26a9 is highly expressed in the apical membrane of parietal cells, surface epithelial cells and deep cells in the gastric glands and is co-localized with H+/K+-ATPase expression (Xu et al., 2005, 2008). The initial characterization of Slc26a9 transport by the measurements of intracellular pH (pHi) suggested that Slc26a9 can function as a Cl/HCO3 exchanger in gastric surface cells to support HCO3- secretion in the stomach, which can be inhibited by NH4+ in vivo (Xu et al., 2005). These results raise the question of whether the expression of Slc26a9 is reduced during Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori, Hp) infection due to the production of ammonia (NH3)/NH4+ through its urease activity, which may predispose patients to acidic injury and peptic ulcers by impairing Slc26a9-mediated gastric HCO3- secretion. However, a subsequent study showed that the mRNA and protein expression levels of Slc26a9 are not altered in gastric surface epithelial cells in Hp-infected mice, which might be a compensatory response to overcome the chronic inhibition of Slc26a9-mediated HCO3- secretion by the Hp infection (Henriksnas et al., 2006). Subsequently, Demitrack et al. demonstrated that Slc26a9 can activate cellular HCO3- secretion through its anion transporter if the gastric epithelium is damaged (Demitrack et al., 2010). Collectively, these observations suggest that Slc26a9 functions as a Cl-/HCO3- exchanger. However, based on a Slc26a9-deficient mouse model, functional experiments have shown that the deletion of Slc26a9 results in impaired acid secretion, indicating that Slc26a9 can function as a Cl- channel (Xu et al., 2008). Moreover, the absence of Slc26a9 expression in the murine stomach at young age causes parietal cell loss, hypochlorhydria and massive fundic hyperplasia (Xu et al., 2008), suggesting that the Slc26a9 gene is essential for parietal cell function and survival. Loss of parietal cells is known to contribute to a premalignant environment in the gastric mucosa, and gastric cancer normally develops in the setting of parietal cell loss and mucous cell metaplasia (Goldenring and Nam, 2010). Thus, Slc26a9 deficiency may promote gastric carcinogenesis and should be intensively investigated.

In the Duodenum

Recently, polymorphisms in the slc26a9 gene were associated with an increased risk of meconium ileus (MI) in infants with cystic fibrosis (CF) (Sun et al., 2012), which addresses the question regarding the expression and function of Slc26a9 in the intestine. Early expression data showed that low levels of Slc26a9 were detected in the duodenum (Xu et al., 2005). However, a significant reduction in basal duodenal HCO3- secretion was observed in Slc26a9-deficient duodenum in vivo, and forskolin-induced stimulation did not alter HCO3- secretion. Additionally, both luminal low acid and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) treatments strongly reduced HCO3- secretion in the absence of Slc26a9 expression, suggesting that Slc26a9 plays an important role in orchestrating the acid-induced duodenal HCO3- secretory response (Singh et al., 2013). Subsequently, a more precise study found that Slc26a9 was detected in the proximal duodenum but not in the more distal part of the intestine where MI occurs (Liu et al., 2015). The loss of Slc26a9 expression resulted in reduced survival of CFTR-deficient mice and strongly impaired HCO3- and fluid secretion in the proximal duodenum, particularly at a young age, indicating that Slc26a9 plays a key role in regulating HCO3- secretory and fluid absorptive changes in the proximal duodenal mucosa despite the low Slc26a9 expression at the whole organ level (Liu et al., 2015). The association between Slc26a9 and MI might be related to the absence or malfunction of Slc26a9 in the upper GI tract, which results in maldigestion and impaired downstream signaling. More importantly, we depict the following four potential ion transport modes of Slc26a9 in the duodenum: a. Slc26a9 is located in the crypts of the duodenum and functions as a chloride channel (similar to CFTR) to facilitate Cl- recycling via another Cl-/HCO3- exchanger, b. Slc26a9 functions as an anion exchanger that is functionally coupled to CFTR to regulate HCO3- secretion, c. Slc26a9 and CFTR interact structurally and/or functionally in a positive fashion to enhance HCO3- secretion, and d. Slc26a9 is a crypt enterocyte anion channel that functions indirectly in transepithelial anion transport but is possibly involved in volume control/apoptosis/migration/differentiation. In this case, the altered ion transport could be a secondary phenomenon based on the changes in cellular growth and differentiation patterns. Therefore, the importance of Slc26a9 in the regulation of HCO3- secretion may offer a new possibility for the protection of duodenum ulcer, as HCO3- secretion is essential for maintaining acid/base homeostasis and mucosal protection in the duodenum.

In the Pancreas and Biliary System

Polymorphisms in Slc26a9 are associated with an increased incidence and poor prognosis of diabetic individuals with CF (Blackman et al., 2013), However, knowledge of the expression and function of Slc26a9 in the pancreas and biliary system is lacking. We found that Slc26a9 was expressed in the pancreatic parenchyma, liver, gallbladder and microdissected pancreatic and bile ducts at low levels (Liu et al., 2015). Afterward, functional data showed that the deletion of Slc26a9 is associated with a reduction in pancreatic fluid, but not HCO3- secretion, in young female mice. This finding demonstrates that Slc26a9 plays a role in pancreatic ductal physiology despite the fairly low expression levels compared to those of CFTR and other electrolyte transporters. Furthermore, a slight reduction in the normalization of blood glucose levels was observed after an intravenous glucose bolus in older female mice. The female preponderance for an Slc26a9-related loss of ductal function is interesting in the context of the higher incidence of diabetes in female CF patients (Li et al., 2016). Thus, Slc26a9 can function as an alternative chloride channel to regulate fluid absorption and glucose metabolism in the pancreas, suggesting that Slc26a9 may not only be involved in CF-related diabetes (CFRD) onset but also may contribute to the occurrence of Type 2 diabetes.

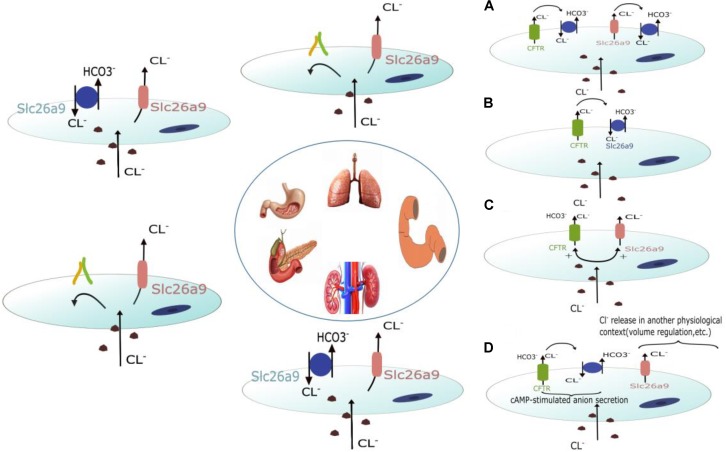

Role of Slc26a9 in the Kidney

Slc26a9 is mainly found in the medulla and cultured medullary collecting duct cells and is located on the apical membrane of a subset of cells in the outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), the initial portion of the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD), and principal cells (Amlal et al., 2013; Soleimani, 2013). Functional analyses showed that the absence of Slc26a9 in mouse results in impaired chloride and sodium excretion after exposure to a high-salt diet or water deprivation. This impairment is accompanied by elevated systemic arterial pressure, suggesting that Slc26a9 functions as a Cl- channel that regulates renal salt excretion and blood pressure (Amlal et al., 2013). However, RT-PCR analyses and pHi measurements in cultured proximal tubular cell lines (PTE) from Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) showed that Slc26a9 is upregulated in SHR PTE cells. Slc26a9 functions as a Cl-/HCO3- exchanger that mediates part of Cl- and HCO3- transport activity in both WKY and SHR cells (Simao et al., 2013). Therefore, the exact ion transport mode of Slc26a9 in the kidney is still controversial. Figure 1 depicts the potential ion transport modes of Slc26a9 in different organs.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram depicting the potential roles of Slc26a9 in different organs. Slc26a9 functions as a Cl- channel in the lung and pancreases. In the stomach and kidney, Slc26a9 can function as both a Cl- channel and Cl-/HCO3- exchanger. In addition to functioning as a Cl- channel and Cl-/HCO3- exchanger, four potential roles of Slc26a9 in the duodenum have been discussed in other organs. Slc26a9 and CFTR may interact structurally and/or functionally in a positive fashion to enhance HCO3- secretion. Slc26a9 is a crypt enterocyte anion channel that functions indirectly with regard to transepithelial anion transport and is possibly involved in volume control/apoptosis/migration/differentiation.

Reciprocal Interaction Between Slc26a9 and CFTR

Several Slc26a9 regulatory mechanisms, including transcription, protein trafficking, post-translational modifications, macro-molecular complex formation (Dorwart et al., 2008) and WNK regulation (Dorwart et al., 2007; Park et al., 2012; Bazúa-Valenti et al., 2015), have been described. The reciprocal regulation between CFTR and Slc26a9 has also been extensively discussed (Dorwart et al., 2008; Fong, 2012; Li et al., 2017) due to the overlapping expression pattern and function of the two proteins in some organs. First, co-immunoprecipitation experiments conducted in HEK293 cells transiently expressing Slc26a9 and CFTR proteins demonstrated the existence of the Slc26a9-CFTR complex (Bertrand et al., 2009). This complex was also confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation in a CF bronchial epithelial cell line (CFBE4Io) stably expressing wild-type or p.phe508del CFTR proteins transduced with Slc26a9 (Avella et al., 2011). The direct interaction between the two proteins was further demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation experiments using the purified Slc26a9 anti-sigma factor antagonist (STAS) domain and purified CFTR R domain (Chang et al., 2009a). Second, Slc26a9 interacts functionally and/or structurally with CFTR when co-expressed heterologously, but whether this interaction results in enhancement or inhibition is controversial. Some findings suggest that Slc26a9 can enhance CFTR-mediated anion secretion in cultured airway cells and Xenopus oocytes (Bertrand et al., 2009; Avella et al., 2011; Ousingsawat et al., 2012), and the reciprocal stimulation of both Slc26a9 and the CFTR current by an STAS-R domain interaction in a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent fashion has been described. This finding is similar to previous descriptions of the interaction between the anion exchangers Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 (Bertrand et al., 2009). Furthermore, we confirmed that a deletion of Slc26a9 reduces survival in CFTR-deficient mice (Liu et al., 2015). Interestingly, Avella et al. also reported that the level of Slc26a9 protein increased in response to co-expression with the CFTR channel (Avella et al., 2011). In contrast, Slc26a9 has been found to inhibit (and be inhibited by) CFTR in non-polarized HEK293 cells (Ousingsawat et al., 2012). Additionally, a recent study showed that Slc26a9 is co-expressed with F508del CFTR, and its trafficking defect led to a PDZ motif-sensitive intracellular retention of Slc26a9 (Bertrand et al., 2017). Therefore, Slc26a9 function and regulation may be highly context-dependent and merit further investigation.

SLC26A9 and Human Diseases

Recent reports have demonstrated that mutations in SLC26A proteins cause a variety of human diseases (Dorwart et al., 2008; El Khouri and Toure, 2014). In humans, pathogenic mutations in slc26a9 have been associated with some diseases as well. Initially, based on a public single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) database, Romero’s group found that slc26a9 polymorphisms cause several functional modifications, including increased or decreased Cl- current and Cl-/HCO3- exchanger activity and altered protein expression, which could lead to a spectrum of pathophysiologies. However, SLC26A9 is not directly associated with any disease (Chen et al., 2012). Nevertheless, a genome-wide pharmacogenomics study investigating neurocognition reported that rs11240594 at slc26a9 mediates the effects of olanzapine on processing speed, indicating that slc26a9 may be a novel candidate gene for antipsychotic responses in schizophrenia (McClay et al., 2011). This study represents the only report associated with the neural system thus far. In the airways, an analysis of a database of a large European cohort of childhood asthma was performed, resulting in the detection of polymorphisms that carried an increased risk of childhood asthma. Indeed, a polymorphism (at rs2282430) in the slc26a9 gene was found to be associated with an increased asthma incidence. Additionally, polymorphisms in the 3′ UTR of slc26a9 that reduce protein expression in vitro are associated with asthma. These data provide initial evidence that SLC26A9 may be involved in asthma pathogenesis in humans, suggesting that SLC26A9 may serve as a therapeutic target for allergic airway diseases (Anagnostopoulou et al., 2012; Mall and Galietta, 2015; Sala-Rabanal et al., 2015). Subsequently, a study involving a cohort of 147 patients presenting with diffuse idiopathic bronchiectasis, corresponding to a common lung disease primarily induced in CF patients, was performed. The authors showed that two missense variants (p. Arg575Trp and p.Val486Ile) in the slc26a9 gene can decrease Cl- channel transport and are related to diffuse idiopathic bronchiectasis, indicating that SLC26A9 is a candidate gene for CF-like disease (Bakouh et al., 2013). Recently, more studies have shown that SNPs in the slc26a9 gene are associated with CF-related disease onset, suggesting that SLC26A9 is a novel CFTR regulator. Sun and colleagues were the first to report that SNPs (at rs4077468) in the slc26a9 gene were significantly associated with increases in MI in CF infants (Sun et al., 2012). Interestingly, another SNP (rs7512462) in the slc26a9 gene was pleiotropic for MI, pancreatic insufficiency and early exocrine pancreatic disease in CF individuals (Li et al., 2014; Soave et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2018) but not progressive lung disease patients (Wright et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014; Corvol et al., 2015). However, new data demonstrated that the rs7512462∗C allele is associated with a better response to ivacaftor (VX-770, C24H28N2O3) in patients with CF and mutations, resulting in improvements in pulmonary function (Pereira et al., 2017). This finding confirmed that Slc26a9 airway modification requires CFTR at the cell surface and that a common variant in Slc26a9 may predict the response to CFTR-directed therapeutics (Strug et al., 2016). Furthermore, Blackman’s group reported that two SNPs in complete linkage disequilibrium (rs4077468 and rs4077469) located within the slc26a9 gene were found to increase the risk of CFRD onset, but the same genetic alterations in slc26a9 played a protective role against Type 2 diabetes predisposition (Blackman et al., 2013; Meyre and Pare, 2013). This finding suggests that the ductal fluid flow in the exocrine pancreas was changed due to abnormal chloride channel function resulting from CFTR mutations and that SNPs at the slc26a9 locus play a substantial role in CFRD, further supporting that Slc26a9 activity might play a role in glucose metabolism (Blackman et al., 2013). Collectively, these studies suggest that SLC26A9 is a disease modifier and novel therapeutic target that may compensate for impaired CFTR-mediated Cl- secretion. Recently, dysfunction of Slc26a9-mediated ion composition was associated with Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) onset (Tandon et al., 2017), according to the alteration of the expression and cellular localization of Slc26a9 in SS saliva when compared with healthy controls (Pedersen et al., 2005; Pijpe et al., 2007). Although most studies have focused on the role of Slc26a9 in CF-related disease onset, we anticipate that Slc26a9 may also be involved in the pathogenesis of some unreported diseases, such as duodenal ulcers, Type 2 diabetes and hypertension, based on functional analysis (Amlal et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). The role of Slc26a9 remains a mystery in many fields and diseases and merits further and intensive investigation. Table 1 lists the SNPs in the slc26a9 gene that are related to different diseases.

Table 1.

SNPs in the slc26a9 gene that have been reported to be related to the onset of diseases.

| Disease | SNPs in the slc26a9 gene | References |

|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | rs11240594 | McClay et al., 2011 |

| Asthma | rs2282430 | Anagnostopoulou et al., 2012 |

| Meconium ileus | rs4077468 rs7512462 | Sun et al., 2012 Li et al., 2014 |

| CF-related diabetes Pancreatic insufficiency and Early exocrine pancreatic disease | rs4077468 rs4077469 rs7512462 | Blackman et al., 2013 Meyre and Pare, 2013 Soave et al., 2014 Li et al., 2014 Miller et al., 2015 |

Summary and Outlook

Slc26a9 is a member of a relatively new Slc26a gene family with multiple functions. Although extensive work has been performed to investigate the expression pattern, functional diversity, regulatory mechanism and pathophysiology of this novel protein in different organs by various systems, the exact physiological and pathophysiological role of Slc26a9 remains a mystery in many fields. Future work should not only further investigate its regulatory role in ion transport but also elucidate the characteristics of its non-ionic transport, i.e., Slc26a9 is possibly involved in volume control/apoptosis/migration/differentiation. Importantly, previous studies mainly focused on the role of Slc26a9 as a disease modifier of CF-related diseases, based on the overlapping expression pattern and function of the two proteins in some organs. However, an increasing number of functional studies have shown that Slc26a9 may also be involved in some non-CF-related diseases, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, schizophrenia and unreported diseases, including duodenal ulcers, Type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Therefore, basic and genetic research is required in the future to determine whether Slc26a9 can be a clinically relevant disease modifier or promising therapeutic target.

Author Contributions

XL and TL performed the work and contributed equally. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (81560456 to XL, 81660098 to TL, and 81572438 to BT), the Outstanding Scientific Youth Fund of Guizhou Province (2017-5608 to XL), and the Scientific Innovation Fund of Returned Overseas of Guizhou Province (2016-14 to XL).

References

- Alper S. L., Sharma A. K. (2013). The SLC26 gene family of anion transporters and channels. Mol. Aspects Med. 34 494–515. 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal H., Xu J., Barone S., Zahedi K., Soleimani M. (2013). The chloride channel/transporter Slc26a9 regulates the systemic arterial pressure and renal chloride excretion. J. Mol. Med. 91 561–572. 10.1007/s00109-012-0973-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou P., Dai L., Schatterny J., Hirtz S., Duerr J., Mall M. A. (2010). Allergic airway inflammation induces a pro-secretory epithelial ion transport phenotype in mice. Eur. Respir. J. 36 1436–1447. 10.1183/09031936.00181209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou P., Riederer B., Duerr J., Michel S., Binia A., Agrawal R., et al. (2012). SLC26A9-mediated chloride secretion prevents mucus obstruction in airway inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 122 3629–3634. 10.1172/JCI60429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avella M., Loriol C., Boulukos K., Borgese F., Ehrenfeld J. (2011). SLC26A9 stimulates CFTR expression and function in human bronchial cell lines. J. Cell. Physiol. 226 212–223. 10.1002/jcp.22328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakouh N., Bienvenu T., Thomas A., Ehrenfeld J., Liote H., Roussel D., et al. (2013). Characterization of SLC26A9 in patients with CF-like lung disease. Hum. Mutat. 34 1404–1414. 10.1002/humu.22382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazúa-Valenti S., Chávez-Canales M., Rojas-Vega L., González-Rodríguez X., Vázquez N., Rodríguez-Gama A., et al. (2015). The effect of WNK4 on the Na+-Cl- cotransporter is modulated by intracellular chloride. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26 1781–1786. 10.1681/ASN.2014050470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand C. A., Mitra S., Mishra S. K., Wang X., Zhao Y., Pilewski J. M., et al. (2017). The CFTR trafficking mutation F508del inhibits the constitutive activity of SLC26A9. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 312 L912. 10.1152/ajplung.00178.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand C. A., Zhang R., Pilewski J. M., Frizzell R. A. (2009). SLC26A9 is a constitutively active, CFTR-regulated anion conductance in human bronchial epithelia. J. Gen. Physiol. 133 421–438. 10.1085/jgp.200810097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman S. M., Commander C. W., Watson C., Arcara K. M., Strug L. J., Stonebraker J. R., et al. (2013). Genetic modifiers of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 62 3627–3635. 10.2337/db13-0510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. H., Plata C., Sindic A., Ranatunga W. K., Chen A. P., Zandi-Nejad K., et al. (2009a). Slc26a9 is inhibited by the R-region of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator via the STAS domain. J. Biol. Chem. 284 28306–28318. 10.1074/jbc.M109.001669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. H., Plata C., Zandi-Nejad K., Sindic A., Sussman C. R., Mercado A., et al. (2009b). Slc26a9–anion exchanger, channel and Na+ transporter. J. Membr. Biol. 228 125–140. 10.1007/s00232-009-9165-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. P., Chang M. H., Romero M. F. (2012). Functional analysis of nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in human SLC26A9. Hum. Mutat. 33 1275–1284. 10.1002/humu.22107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvol H., Blackman S. M., Boelle P. Y., Gallins P. J., Pace R. G., Stonebraker J. R., et al. (2015). Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies five modifier loci of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 6:8382. 10.1038/ncomms9382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demitrack E. S., Soleimani M., Montrose M. H. (2010). Damage to the gastric epithelium activates cellular bicarbonate secretion via SLC26A9 Cl(-)/HCO(3)(-). Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 299 G255–G264. 10.1152/ajpgi.00037.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorwart M. R., Shcheynikov N., Wang Y., Stippec S., Muallem S. (2007). SLC26A9 is a Cl(-) channel regulated by the WNK kinases. J. Physiol. 584(Pt 1), 333–345. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorwart M. R., Shcheynikov N., Yang D., Muallem S. (2008). The solute carrier 26 family of proteins in epithelial ion transport. Physiology 23 104–114. 10.1152/physiol.00037.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khouri E., Toure A. (2014). Functional interaction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator with members of the SLC26 family of anion transporters (SLC26A8 and SLC26A9): physiological and pathophysiological relevance. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 52 58–67. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong P. (2012). CFTR-SLC26 transporter interactions in epithelia. Biophys. Rev. 4 107–116. 10.1007/s12551-012-0068-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenring J. R., Nam K. T. (2010). Oxyntic atrophy, metaplasia, and gastric cancer. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 96 117–131. 10.1016/B978-0-12-381280-3.00005-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksnas J., Phillipson M., Storm M., Engstrand L., Soleimani M., Holm L. (2006). Impaired mucus-bicarbonate barrier in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291 G396–G403. 10.1152/ajpgi.00017.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz R. S., Smith C. E., Bringas P., Chen Y., Smith S. M., Snead M. L., et al. (2012). Identification of novel candidate genes involved in mineralization of dental enamel by genome-wide transcript profiling. J. Cell. Physiol. 227 2264–2275. 10.1002/jcp.22965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Salomon J. J., Sheppard D. N., Mall M. A., Galietta L. J. (2017). Bypassing CFTR dysfunction in cystic fibrosis with alternative pathways for anion transport. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 34 91–97. 10.1016/j.coph.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Riederer B., Liu X., Pallagi P., Singh A. K., Soleimani M., et al. (2016). Loss of Slc26a9 anion transporter results in reduced pancreatic fluid secretion in young female mice. Gastroenterology 150 S915–S915. [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Soave D., Miller M. R., Keenan K., Lin F., Gong J., et al. (2014). Unraveling the complex genetic model for cystic fibrosis: pleiotropic effects of modifier genes on early cystic fibrosis-related morbidities. Hum. Genet. 133 151–161. 10.1007/s00439-013-1363-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Li T., Riederer B., Lenzen H., Ludolph L., Yeruva S., et al. (2015). Loss of Slc26a9 anion transporter alters intestinal electrolyte and HCO3(-) transport and reduces survival in CFTR-deficient mice. Pflugers Arch. 467 1261–1275. 10.1007/s00424-014-1543-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Riederer B., Anagnostopoulou P., Li T., Yu Q., Rausch B., et al. (2014). Absence of Slc26a9 results in altered tracheobronchial anion transport and high mortality in neonate mice (1181.7). FASEB J. 28(1 Suppl.),1181–1187.24285091 [Google Scholar]

- Lohi H., Kujala M., Makela S., Lehtonen E., Kestila M., Saarialho-Kere U., et al. (2002). Functional characterization of three novel tissue-specific anion exchangers SLC26A 7, -A8, and -A9. J. Biol. Chem. 277 14246–14254. 10.1074/jbc.M111802200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loriol C., Dulong S., Avella M., Gabillat N., Boulukos K., Borgese F., et al. (2008). Characterization of SLC26A 9, facilitation of Cl(-) transport by bicarbonate. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 22 15–30. 10.1159/000149780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M. A., Galietta L. J. (2015). Targeting ion channels in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 14 561–570. 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClay J. L., Adkins D. E., Aberg K., Bukszar J., Khachane A. N., Keefe R. S., et al. (2011). Genome-wide pharmacogenomic study of neurocognition as an indicator of antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 36 616–626. 10.1038/npp.2010.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyre D., Pare G. (2013). Genetic dissection of diabetes: facing the giant. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 62 3338–3340. 10.2337/db13-1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. R., Soave D., Li W., Gong J., Pace R. G., Boelle P. Y., et al. (2015). Variants in solute carrier SLC26A9 modify prenatal exocrine pancreatic damage in cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 166 1152.e6–1157.e6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.01.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount D. B., Romero M. F. (2004). The SLC26 gene family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Pflugers Arch. 447 710–721. 10.1007/s00424-003-1090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohana E., Yang D., Shcheynikov N., Muallem S. (2009). Diverse transport modes by the solute carrier 26 family of anion transporters. J. Physiol. 587 2179–2185. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ousingsawat J., Schreiber R., Kunzelmann K. (2012). Differential contribution of SLC26A9 to Cl(-) conductance in polarized and non-polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 227 2323–2329. 10.1002/jcp.22967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Hong J. H., Ohana E., Muallem S. (2012). The WNK/SPAK and IRBIT/PP1 pathways in epithelial fluid and electrolyte transport. Physiology 27 291–299. 10.1152/physiol.00028.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A. M., Bardow A., Nauntofte B. (2005). Salivary changes and dental caries as potential oral markers of autoimmune salivary gland dysfunction in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. BMC Clin. Pathol. 5:4. 10.1186/1472-6890-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S. V. N., Ribeiro J. D., Bertuzzo C. S., Marson F. A. L. (2018). Interaction among variants in the SLC gene family (SLC6A 14, SLC26A 9, SLC11A 1, and SLC9A3) and CFTR mutations with clinical markers of cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 53 888–900. 10.1002/ppul.24005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V. N., Ribeiro J. D., Bertuzzo C. S., Marson F. A. L. (2017). Association of clinical severity of cystic fibrosis with variants in the SLC, gene family ( SLC6A 14, SLC26A 9, SLC11A 1, AND SLC9A3 ). Gene 629 117–126. 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijpe J., Kalk W. W. I., Bootsma H., Spijkervet F. K. L., Kallenberg C. G. M., Vissink A. (2007). Progression of salivary gland dysfunction in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66 107–112. 10.1136/ard.2006.052647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala-Rabanal M., Yurtsever Z., Berry K. N., Brett T. J. (2015). Novel roles for chloride channels, exchangers, and regulators in chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:497387. 10.1155/2015/497387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon J. J., Spahn S., Wang X., Fullekrug J., Bertrand C. A., Mall M. A. (2016). Generation and functional characterization of epithelial cells with stable expression of SLC26A9 Cl- channels. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 310 L593–L602. 10.1152/ajplung.00321.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simao S., Gomes P., Pinho M. J., Soares-da-Silva P. (2013). Identification of SLC26A transporters involved in the Cl(-)/HCO(3)(-) exchange in proximal tubular cells from WKY and SHR. Life Sci. 93 435–440. 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K., Liu Y., Riederer B., Engelhardt R., Thakur B. K., Soleimani M., et al. (2013). Molecular transport machinery involved in orchestrating luminal acid-induced duodenal bicarbonate secretion in vivo. J. Physiol. 591 5377–5391. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.254854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soave D., Miller M. R., Keenan K., Li W., Gong J., Ip W., et al. (2014). Evidence for a causal relationship between early exocrine pancreatic disease and cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a mendelian randomization study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 63 2114–2119. 10.2337/db13-1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani M. (2013). SLC26 CL - /HCO 3 -, exchangers in the kidney: roles in health and disease. Kidney Int. 84 657–666. 10.1038/ki.2013.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strug L. J., Gonska T., He G., Keenan K., Ip W., Boelle P. Y., et al. (2016). Cystic fibrosis gene modifier SLC26A9 modulates airway response to CFTR-directed therapeutics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25 4590–4600. 10.1093/hmg/ddw290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Rommens J. M., Corvol H., Li W., Li X., Chiang T. A., et al. (2012). Multiple apical plasma membrane constituents are associated with susceptibility to meconium ileus in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 44 562–569. 10.1038/ng.2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon M., Perez P., Burbelo P. D., Calkins C., Alevizos I. (2017). Laser microdissection coupled with RNA-seq reveal cell-type and disease-specific markers in the salivary gland of Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 35 777–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright F. A., Strug L. J., Doshi V. K., Commander C. W., Blackman S. M., Sun L., et al. (2011). Genome-wide association and linkage identify modifier loci of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis at 11p13 and 20q13.2. Nat. Genet. 43 539–546. 10.1038/ng.838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Henriksnas J., Barone S., Witte D., Shull G. E., Forte J. G., et al. (2005). SLC26A9 is expressed in gastric surface epithelial cells, mediates Cl-/HCO3- exchange, and is inhibited by NH4+. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289C493–C505. 10.1152/ajpcell.00030.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Song P., Miller M. L., Borgese F., Barone S., Riederer B., et al. (2008). Deletion of the chloride transporter Slc26a9 causes loss of tubulovesicles in parietal cells and impairs acid secretion in the stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 17955–17960. 10.1073/pnas.0800616105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin K., Lei Y., Wen X., Lacruz R. S., Soleimani M., Kurtz I., et al. (2015). Slc26a gene family participate in pH regulation during enamel maturation. PLoS One 10:e0144703. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]