Abstract

Background

Adoptive cell therapy employing natural killer group 2D (NKG2D) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells has demonstrated preclinical efficacy in several model systems, including hematological and solid tumors. We present comprehensive data on manufacturing development and clinical production of autologous NKG2D CAR T cells for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma (NCT02203825). An NKG2D CAR was generated by fusing native full-length human NKG2D to the human CD3ζ cytoplasmic signaling domain. NKG2D naturally associates with native costimulatory molecule DAP10, effectively generating a second-generation CAR against multiple ligands upregulated during malignant transformation including MIC-A, MIC-B and the UL-16 binding proteins.

Methods

CAR T cells were infused fresh after a 9-day process wherein OKT3-activated T cells were genetically modified with replication- defective gamma-retroviral vector and expanded ex vivo for 5 days with recombinant human interleukin-2.

Results

Despite sizable interpatient variation in originally collected cells, release criteria, including T-cell expansion and purity (median 98%), T- cell transduction (median 66% CD8+ T cells), and functional activity against NKG2D ligand-positive cells, were met for 100% of healthy donors and patients enrolled and collected. There was minimal carryover of non-T cells, particularly malignant cells; both effector memory and central memory cells were generated; and inflammatory cytokines such as GM-CSF, RANTES, IFN-γ and TNFα were selectively upregulated.

Discussion

The process resulted in production of required cell doses for the first-in-human Phase I NKG2D CAR T clinical trial, and provides a robust, flexible base for further optimization of NKG2D CAR T-cell manufacturing.

Keywords: Chimeric Antigen Receptor, NKG2D, GMP cell therapy, CAR T, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Multiple Myeloma, gamma retrovirus

Introduction

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cells are targeted, genetically engineered cellular therapies that can invoke rapid and specific anti-tumor activity, while providing sustained responses. Canonical CAR T cells are engineered using constructs encoding a single chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from a murine or human antibody, a costimulatory domain connected by a hinge region, and the cytoplasmic signaling domain of CD3ζ [1, 2]. This typically restricts CAR T cells to recognizing a single tumor antigen on a limited subset of tumors, such as CD19 in B-cell malignancies [3, 4]. Such CAR T cells have shown impressive clinical results, whereas successful CAR T-cell therapies for other hematologic malignancies and solid tumors have proven more challenging [5, 6].

Natural killer (NK) cells recognize tumor cells in vitro and in vivo using a series of activating and inhibitory receptors to distinguish tumors from normal cells [7, 8]. Ligands for NKG2D, an NK cell activating receptor, can be found in hematologic malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemias, myelodysplastic syndromes and myelomas and are also detected in solid tumors derived from colon, breast, prostate, ovary, lung, brain, liver, and kidney [8, 9]. In total, more than 70% of human cancers have evidence of NKG2D ligand expression. We have produced a chimeric NKG2D receptor (NKG2D CAR) by fusing the full-length human NKG2D gene with the cytoplasmic signaling domain of CD3ζ thereby endowing engineered T cells with activity against NKG2D ligands. These include MIC-A, MIC-B, and the UL-16 binding proteins commonly upregulated in malignancy, infections or settings of cell stress but largely absent on the surface of healthy cells [8, 10]. NKG2D naturally associates with the natively-encoded adaptor protein DAP10 that provides a co-stimulatory signal upon ligand binding, effectively making this NKG2D CAR a “second-generation” receptor. The only ‘foreign’ sequence of the construct is the intracellular fusion between the NKG2D and CD3ζ proteins, yielding a receptor with potentially low immunogenicity.

In the present study, we describe a process to produce therapeutic doses of autologous NKG2D CAR T cells for a Phase I clinical trial to treat relapsed acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and multiple myeloma (MM). Methods used to produce CAR T cells, in addition to genetic construct and clinical trial design, are essential determinants of in vivo efficacy. Thus, comprehensive characterization of manufacturing steps and the CAR product composition at each step is key to advancing the field. Stepwise efforts to improve scalability, cost and reproducibility are necessary and may well enable the broad commercialization of these products.

The NKG2D CAR T cells in this study were produced through a 9-day in vitro process described extensively below involving OKT3-activated T cells genetically modified with a replication-defective gamma-retroviral vector and ex vivo expansion in gas-permeable culture devices. This process, first in cells collected from healthy donors and then in cells derived from patients with AML/MDS or MM, generated products with consistent viability and T-cell purity, robust in vitro expansion kinetics, high vector-mediated surface expression of NKG2D on both CD8+ and CD4+ T cell subsets, and reproducible in vitro functional activity. This process supported a dose-escalation Phase I clinical trial and provides a platform for future NKG2D CAR development in multiple disease settings.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and patient sample collection

All healthy donor cells and AML/MDS or MM donor cells at either Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center or Dana-Farber Cancer institute (DFCI) were obtained after informed consent under IRB-approved banking or clinical trial protocols, or purchased from commercial entities. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) were isolated using Lymphoprep (StemCells Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) or Ficoll-Pacque Premium (GE, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Human cell lines used were NKG2D-ligand positive RPMI 8866, Panc-1, K562 or NKG2D-ligand negative P815 (see Supplemental Methods).

Construction and production of NKG2D CAR gamma-retroviral vector

The NKG2D CAR construct contains full-length NKG2D fused to the intracellular CD3ζ cloned into a Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (Mo-MuLV)-based vector. For virus production, we used the PG13 packaging cell line expressing the gibbon ape leukemia virus env and the Mo-MuLV gag-pol proteins. For research grade-vector, PG13 clones expressing NKG2D CAR were generated by transfecting GP2-293T cells with NKG2D CAR DNA expression vector and VSV-G gene. After 72 hours, cell supernatant from transfected GP2-293T cells was used to transduce PG13 cells at least 3 times with transient virus. Transduced PG13 cells were expanded for both cryopreservation and virus production. Cells plated for virus production were allowed to produce virus for up to 72 hours. Virus supernatants were harvested and filtered through a 0.45 um filter. Virus supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. A small aliquot was used for titration using a retrovirus titration kit by qRT-PCR (Takara, Mountain View, CA, USA). GMP grade clinical virus was produced by Rimedion at Indiana University Vector Production Facility (IUVPF).

Generation of clinical grade NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells

Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected at Day −8 were incubated with 40 ng/mL of anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (OKT3 clone, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) for 48 hours in X-Vivo 15 medium (Lonza, Portsmouth, NH, USA) supplemented with 5% human AB serum (Gemini Bio-Products, Sacramento, CA, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza) and 100 U/mL of recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) (Proleukin, Novartis, Frimley, UK) in T75 cm2 cell culture flasks at 1×106 cells/mL. Activated T cells were transduced twice with NKG2D CAR retroviral supernatant in retronectin-coated (Takara) 24-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/mL in the presence of 100 U/mL of rhIL-2 at Days −6 and −5. Forty ng/mL of anti-human CD3 mAbs were added to the first transduction. Mock T cells were plated in complete medium without retrovirus. After the second round of transduction, NKG2D CAR T or Mock T cells were transferred into G-Re×100 Flasks (Wilson Wolf, St Paul, MN, USA) in complete X-Vivo 15 media supplemented with 100 U/mL of rhIL-2 for 5 days. On the day of harvest, Day 0, NKG2D CAR or Mock T cells were resuspended in Plasma-Lyte (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) plus 1% Human Serum Albumin (Grifols, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Total viable cells were counted using trypan blue dye. NKG2D CAR cells were dosed based on the number of viable CD3+ T cells as determined by flow cytometry. For stability studies, cells from both Mock and NKG2D CAR T cells at 5×106/mL were stored in Plasma-Lyte supplemented with 1% HSA at 4°C. Cell counts, viability, flow cytometry characterization were performed at 24 and 48 hours.

Surface immunophenotyping by FACS analysis

Starting PBMCs and the final product was stained for multiple surface markers to determine granulocyte, monocyte, immature blast-like cell, NK-cell, B-cell and T-cell subset composition (Supplementary Methods). These included CD11b, CD33, CD14; CD34; CD14, CD45; CD16, CD56; CD10, CD38, CD138; and CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RO, CCR7 and CD314/NKG2D, respectively. Given that CD8+ T cells express native NKG2D which cannot be differentiated from NKG2D-CAR expression by surface staining, a baseline threshold of native NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells was defined as the fluorescence intensity exceeded by only 5% of CD8+ T cells in a parallel Mock T cell culture. Vector-driven NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells was calculated as the expression on transduced cells over that Mock-derived threshold (Fig. 2B). Isotype controls were used to quantify NKG2D expression on CD4+ T cells.

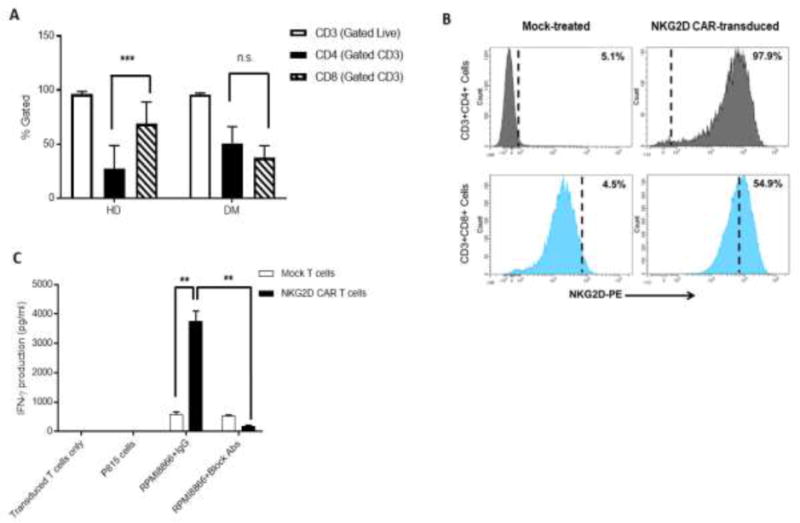

Figure 2.

NKG2D CAR-transduced T-cell product phenotype and in vitro functional activity – pre-clinical results. Surface expression analysis by flow cytometry of (A) CD3 (open bars), CD4 (black bars) and CD8 (striped bars) in product samples manufactured from HDs (n=17) and DMs (n=6); (B) Transduction efficiency in the final product from a representative healthy donor based on surface vector-driven NKG2D CAR expression on CD8+ T cells. Any expression above 5% Mock background (dashed vertical line) was considered due to vector expression. (C) IFN-γ production by ELISA of Mock-treated (open bars) and NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells (black bars) in response to cells with (RPMI8866) and without (P815) NKG2D ligand expression, incubated with either anti-NKG2D blocking Abs or control IgG Abs. NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells alone were plated as controls. Data shown is from one representative donor. Error bars represent SD of triplicates. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; n.s indicates not significant, p> 0.05.

Cytokine release assays

NKG2D CAR T cells from healthy donors or those with malignancies were co-cultured at the ratio of 1:1 with NKG2D ligand-positive cells Panc-1, RPMI 8866, and K562; the NKG2D-ligand negative cell line P815; or medium alone for 24 hours. Cell-free media was harvested and concentrations of IFN-γ were determined by ELISA (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Supernatants were also used in Multiplex assays to determine the concentrations of TNF-α, GM-CSF, RANTES, IL-13, IL-5 and IL-10.

Quantitative Real-Time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for vector copy number (VCN) per cell and for replication competent retrovirus (RCR)

Quantitative PCR for VCN was performed on total DNA from NKG2D products using primers and a labeled probe (Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT], Marlton, NJ, USA) specific for the fusion region of the NKG2D CAR construct. One million NKG2D CAR T cells were processed and 100ng of DNA were used per reaction under the following thermocycler conditions: 1) 95°C for 3 minutes, 2) 95°C for 5 seconds, 3) 56.5°C for 20 seconds, [total of 40 cycles], on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Forward primer (5′-GCCACCAAGGACACCTAC-3′), reverse primer (5′-CTCATCTCCCAGCTGTGTC-3′), probe (5′-[FAM]-AATTCGGGTGGATTCGTGGTCGG-[BHQ]-3′) were included in the reaction in combination with SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Copies of retroviral DNA per cell were estimated based on a standard curve created by serial dilution of NKG2D-CAR plasmid DNA spiked into a genomic DNA background.

For RCR, DNA was isolated from the 1×106 NKG2D CAR T cells and PG13 cells. Primers (IDT) used were: GALV 5′II: 5′-ACCACAGGCGACAGACTTTTT-3′ and GALV3′II: 5′-TGAGACAGCCTCTCTTTTAGTCCT-3′. PCR-certified water and PG13 DNA were used as negative and positive controls (500 bp for the GALV gene amplification), respectively, and cells and cell supernatant from NKG2D CAR T cell cultures were evaluated for the presence of this gene. PCR reactions were run under the following conditions: 95°C denaturation, 65°C annealing, and 72°C extension for a total of 35 cycles. Amplified samples were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel in 1X TAE SyberSafe (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and visualized under UV light. The presence or absence of a 500bp band was noted for the NKG2D CAR T samples.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as median and range, and categorical variables were summarized as number and percentages. Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests were used to compare the difference between paired samples. Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests or 2 sample t tests were used to compare the difference between 2 independent groups. Kruskal Wallis tests were used to compare 2 or more independent samples.

Results

Process characteristics: cell manipulation, transduction and expansion

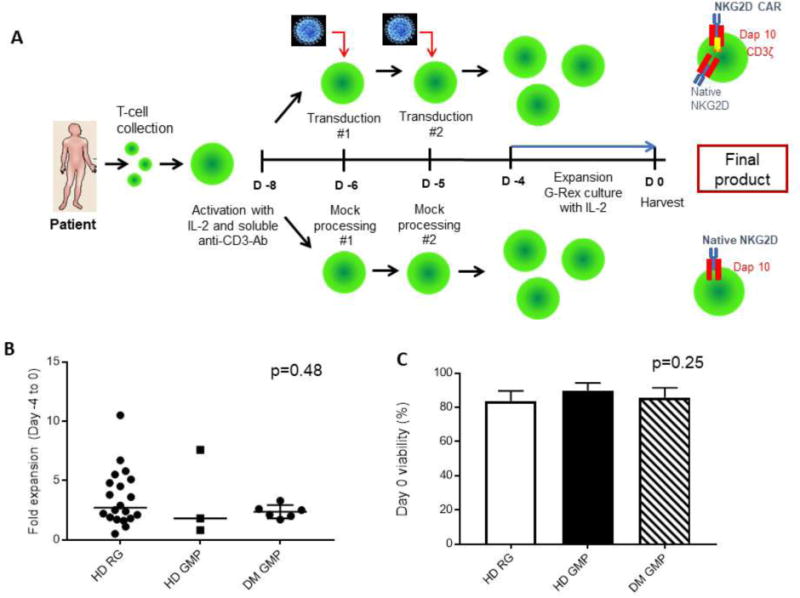

To optimize pre-clinical manufacturing of NKG2D CAR T cells, processes were run using PBMCs from 17 healthy donors. OKT3 and rhIL-2-stimulated PBMCs were transduced twice with viral supernatant from PG13 packaging cells expressing the NKG2D CAR virus, and cells expanded in G-Rex flasks in the presence of rhIL-2 (Fig. 1A). T-cell cultures were initiated either from fresh or cryopreserved PBMCs following Ficoll-density centrifugation. After 9 days, each culture was analyzed for cell expansion, cell viability, transduction efficiency, cell phenotype and functional activity. We observed a median fold-expansion of 2.9 in G-Rex flasks for research grade (RG) processes from 20 healthy donor runs (HD) between Days −4 to 0 (time of harvest), with 84% viability at harvest (Fig. 1B and C). Clinical grade (GMP) parallel runs were performed at both the Cell Manufacturing Core Facility (CMCF) at DFCI and Celdara Medical (CM). Three independent healthy donor samples underwent processing with GMP-grade reagents and showed statistically similar cell expansions and viabilities to those observed during process development using RG reagents. To evaluate the robustness of the process, PBMC samples isolated from 6 AML or MM patients, referred to jointly as donors with malignancies (DM), were used to produce NKG2D CAR T cells using GMP-grade reagents. We observed a median fold-expansion of 2.1 (p =0.48) from Days −4 to 0 and final viability of 86% across all pre-clinical runs (p=0.25) (Fig. 1B and C). Characterization of the final product was based on expression of multiple cell markers (Supplemental Methods). CD3+ T cells comprised almost the entire final product for both HDs and DMs, with median levels greater than 97%. A significant skewing towards CD8+ T cells was noticed in HD-derived (p=0.0007) but not in DM-derived products (p=0.16), with a significant difference in CD4/8 ratio between the 2 groups (p=0.003) (Fig. 2A). While the exact reason for this is unclear, exposure to prior chemotherapies and immunomodulatory agents such as lenalidomide during treatment for malignancy may affect both apheresis and final product composition from donors with malignancies. Due to high endogenous expression levels of NKG2D in CD8+ cells, a 5% baseline threshold for NKG2D expression was set using Mock-treated T cells. The percentage of cells expressing NKG2D at a level above the Mock threshold was used as a readout of vector-specific NKG2D surface expression and thus transduction efficiency. Representative NKG2D surface expression of Mock and NKG2D CAR T cells from a representative healthy donor is shown in Fig. 2B. Comparable transduction efficiencies were observed in additional HD and DM donors during the optimization phase.

Figure 1.

Manufacturing process with healthy donors (HD) and donors with malignancies (DM) – pre-clinical results. (A) Manufacturing workflow for production of Mock-treated and NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells. (B) Fold-expansion of NKG2D CAR T cells from Day −4 to 0. Each dot represents a donor. Bars indicate the mean. (C) Viability of NKG2D CAR-transduced T-cell product measured at Day 0 (harvest) by Trypan Blue exclusion. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD). HD RG n=20 runs from 17 donors; HD GMP n=3; DM GMP n=6. IL-2: Interleukin-2; Ab: Antibody; RG: Research-grade manufacturing; GMP: Clinical-grade manufacturing.

NKG2D CAR T cells mediate a robust and specific biological activity against NKG2D ligand-expressing tumor cells

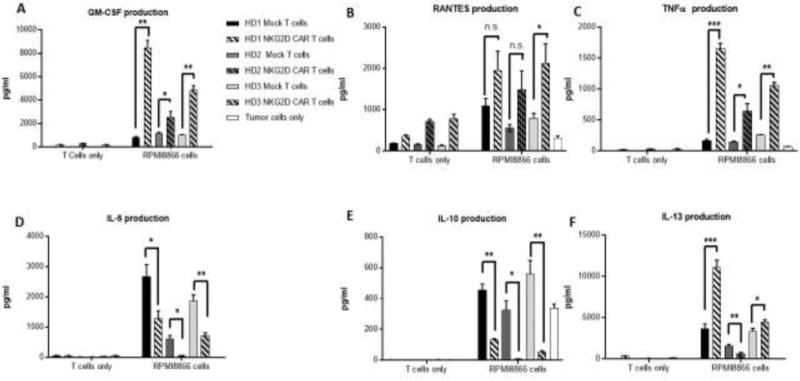

To address the efficacy of NKG2D CAR T cells against tumor cell lines, Mock or NKG2D CAR T cells were co-cultured with NKG2D ligand-positive RPMI 8866 or NKG2D ligand-negative P815 cells (Fig. 2C). NKG2D CAR T cells secreted significantly higher levels of IFN-γ compared to Mock T cells when cultured with RPMI 8866 cells (p=0.003). IFN-γ production was inhibited by addition of NKG2D-blocking antibodies (Abs), demonstrating specific recognition through NKG2D (p=0.003). Moreover, Mock T cells secreted low amounts of IFN-γ in the presence of RPMI 8866, regardless of presence of blocking antibody, further supporting activation through the CAR molecule. Secretion of additional anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines was determined by multiplex analysis after coculture with RPMI 8866 (Fig. 3). Compared to Mock T cells, NKG2D CAR T cells from 3 healthy donors secreted significantly higher amounts of the proinflammatory cytokines GM-CSF (p≤0.04), TNFα (p≤0.02), and there was a trend for greater CCL5 production (p≤0.07) (Fig. 3A-C). In all except one instance, cytokine/chemokine production by NKG2D-CAR T cells was significantly higher in response to RPMI8866 than by NKG2D CAR T cells alone (p values not shown). The production of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 (p≤0.01) and IL-5 (p≤0.01) by NKG2D CAR T cells was significantly lower than by Mock T cells (Fig. 3D-E). IL-13 production by NKG2D CAR T cells was variable across donors (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Cytokine secretion by Multiplex assay of Mock-treated and NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells alone or after coculture with ligand-expressing tumor cells RPMI8866. Human Mock-treated T cells (solid bars) or NKG2D CARs-transduced T cells (striped bars) derived from 3 healthy donors were co-cultured with the NKG2D ligand-expressing RPMI8866 cell line. Tumor cells alone are shown in white bars. Culture supernatants were analyzed for the levels of cytokines (A) GM-CSF, (C) TNF-α, (D) IL-5, (E) IL-10, and (F) IL-13, and the chemokine (B) CCL5 (RANTES). Error bars represent SD of triplicate wells within one run. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; n.s indicates not significant, p≥0.05.

Clinical trial manufacturing of NKG2D CAR T cells: cell manipulation and expansion characteristics

Cells from 12 patients enrolled in the Phase I clinical trial at DFCI were collected either by venipuncture (n=6) or apheresis (n=6) per PI discretion, depending upon absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC). In general, AML patients had higher median ALCs than patients with myeloma (920 versus 500, p=0.04). The median number of total nucleated cells (TNC) collected through apheresis was much higher compared to those collected by venipuncture, as expected (234.5 versus 26.4×107, p=0.008). Merging both collection processes, median recovery following Ficoll collection was 139×107 (7 - 390) cells. Median percentage of CD3+ of TNC (38%, range, 3-69%), numbers of CD3+ cells plated, and subsequent cell counts are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Trial Product Expansion and Characterization

| Patient (Peripheral Blood counts) | Characteristic Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×10^9/uL) | 2.3 | 0.7 | 7.2 |

| ALC (×10^6/uL) | 650* | 110 | 2370 |

| Product Characteristic | |||

| TNC Post Ficoll (×10^7) | 139.1 | 7 | 390 |

| TNC Trypan Blue Viability Day −8 | 98% | 94% | 99% |

| Viable TNC Plated Day −8 (×10^7) | 40 | 6.9 | 40 |

| % CD3 of TNC Plated Day −8 | 36% | 3% | 69% |

| Viable CD3 Plated Day −8 (×10^7) | 9.6 | 1.2 | 24.5 |

| TNC Fold Expansion, Day −8 to −6 | 0.6* | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| TNC Trypan Blue Viability Day −6 | 92% | 77% | 96% |

| CD3 Fold Expansion, Day −8 to −6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| NKG2D CAR-Transduced | |||

| Viable TNC Transduced Day −6 (×10^7) | 9.6 | 4.3 | 9.6 |

| Viable CD3 Transduced Day −6 (×10^7) | 3.1 | 0.2 | 7.3 |

| TNC Fold Expansion Day −6 to −4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| TNC Trypan Blue Viability Day −4 | 84% | 65% | 98% |

| Viable TNC seeded to Grex Day −4 (×10^7) | 8.5 | 3.4 | 16.7 |

| Viable TNC Harvested Day 0 (×10^7) | 14.8 | 7.6 | 170.0 |

| Trypan Blue Viability Day 0 (%) | 81% | 75% | 92% |

| Viable CD3 Harvested Day 0 (×10^7) | 13.8 | 7.2 | 162.0 |

| TNC Fold Expansion Day −4 to 0 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 23.0 |

| TNC Fold Expansion, Day −6 to 0 | 2 | 1 | 18 |

| CD3 Fold Expansion, Day −6 to 0 | 8 | 2 | 54 |

| CD4 Fold Expansion, Day −6 to 0 | 6 | 1 | 112 |

| CD8 Fold Expansion, Day −6 to 0 | 9 | 2 | 65 |

WBC: White Blood cells; ALC: Absolute Lymphocyte Count; TNC: Total Nucleated Cells

p<0.05, indicates the values are significantly different between cultures derived from 7 subjects with AML versus 5 subjects with MM.

Cultures were initiated immediately after Ficoll-density centrifugation. Up to 4×106 cells from each patient were activated on Day −8; in 3 patients fewer cells were obtained after venipuncture. After 2 days of activation in culture and a median fold-expansion of 1 (range, 0.26-1.33; AML median 0.91 versus MM median 0.44, p=0.03), cells underwent a first transduction with the clinical NKG2D CAR virus or mock-treated as described above. A maximum of two 24-well plates (106 live cells/well) were transduced per patient, depending on cell yield after stimulation. After the second transduction at 1 day later (Day −4), all Mock or NKG2D CAR T cells were transferred into G-Rex flasks in the presence of complete fresh media and rhIL-2. Fold-expansion in the clinical runs was tracked from Day −6 to 0. The median fold-expansions for TNC and CD3+ were 2 (range, 1 – 18) and 8 (range, 2 – 54), respectively, demonstrating concurrent T-cell expansion and elimination of other cell types contaminating the culture (Table 1). At Day 0, a median of 13.8×107 (7.2 – 162) CD3+ cells were harvested with 80% viability (range, 75 – 92%). All patients met their required cell dose, which escalated from 1×106 to 3×107 viable CD3+ cells during the clinical trial.

Clinical trial manufacturing of NKG2D CAR T cells: final product composition and transduction efficiency

On Days −8 and 0, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for T-cell, B-cell, monocytic and myeloid markers, viability by 7-AAD exclusion, and transduction efficiency (Day 0 only) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1). When gating on lymphocytes (Table 2A), final products showed median T-cell purity of 98% (AML 95% vs MM 99%, p=0.04), despite starting products that had as few as 3% CD3+ cells. The final CD8 and CD4 product frequencies were highly variable between patients. CAR T-cell products from AML patients had lower CD8+ and higher CD4+ percentages than did products from MM patients (CD8%, median AML 26% vs MM 57%, p=0.02; CD4%, median AML 69% vs MM 31%, p=0.03), despite no differences existing at collection. There was no clear correlation between %CD4 or CD8 at collection and at harvest in a given patient (correlation coefficients 0.3 and 0.24, respectively).

Table 2.

Clinical Trial Product Phenotype Before and After Processing.

| Day −8 Post Ficoll | Day 0 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| A. | ||||||

| % Lymphs (of CD45+ Cells) | 52 | 11 | 87 | 65 | 39 | 95 |

| % CD3+ T Cells (of Lymphs) | 79 | 4 | 96 | 98* | 79 | 100 |

| % CD4+ T Cells (of CD3+) | 56 | 21 | 89 | 57* | 7 | 90 |

| % CD8+ T Cells (of CD3+) | 37 | 7 | 76 | 36* | 7 | 89 |

| % CD19+ B cells (of Lymphs) | 3 | <0.1 | 13 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 17 |

| % Vector-specific NKG2D Expression (of CD4+)# | 93 | 74 | 99 | |||

| % Vector-specific NKG2D Expression (of CD8+)# | 66 | 15 | 87 | |||

| B. | ||||||

| % 7-AAD Negative Live “Lymphs/Monos” (by FSC/SSC) | 100 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 91 | 100 |

| % 7-AAD Negative Live “Granulocytes” (by FSC/SSC) | 77 | 40 | 95 | 18* | 8 | 50 |

| % CD33+/CD11b+ “Myeloid Cells” (of Live Cells) | 17 | 0.9 | 51 | 0.2 | <0.1 | 5 |

| % CD14+ “Monocytic Cells” (of Live Cells) | 13* | 1 | 52 | 0.2 | <0.1 | 4 |

| % CD34+ “AML Blasts” (of Lives Cells) | 2* | 0.5 | 84 | |||

| AML Patients | 32 | 1 | 84 | 0.1 | <0.1 | 6 |

| Myeloma Patients | <1 | <1 | <1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| C. | ||||||

| % CD38+/CD138+/CD3− “Plasma Cells” (of Live Cells) | 0.3 | <0.1 | 2 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 4 |

Note: Data were generated utilizing a unique combination of flow cytometry reagents for each of the 3 panels A, B and C. Within Panel A, there were 2 sets of reagents used, one incorporating NKG2D on Day 0 as indicated by

Monos: Monocytes; Lymph: Lymphocytes; FCS: Forward Scatter; SSC: Side Scatter.

p<0.05. Indicates that these values were significantly different between cultures derived from 7 subjects with AML versus the 5 subjects with MM.

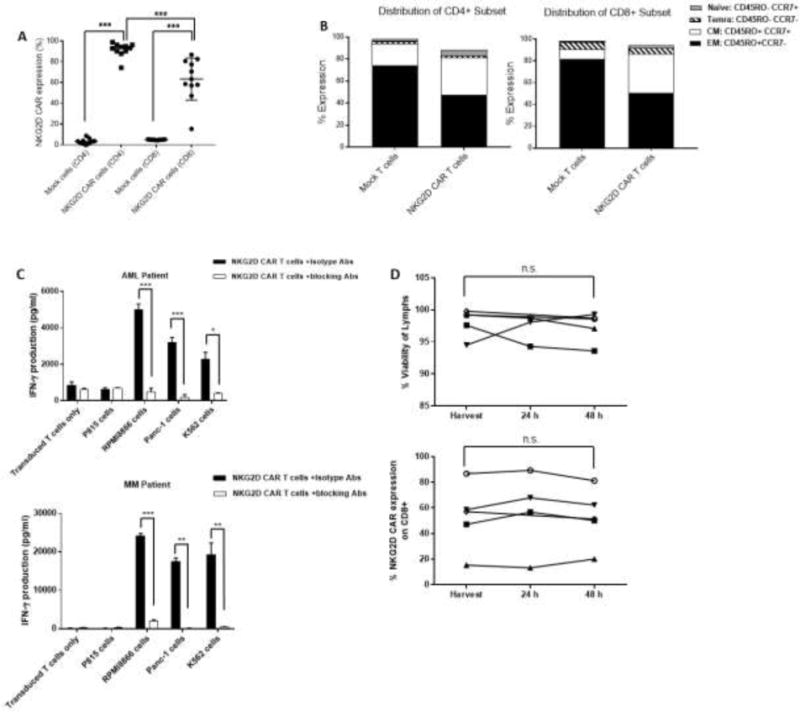

Median transduction efficiency was 66% (range, 15 – 87%) and 93% (range, 74 – 99%) in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively (p<0.0001) (Table 2 and Fig. 4A). With respect to T-cell phenotype, we observed a predominant population of CD45RO+ and CCR7-effector memory (EM) cells (CD8+, median 51%, range, 39-73%; CD4+, median 48%, range, 32-70) with a significant proportion of CD45RO+CCR7+ central memory (CM) cells as well (CD8+, 36%, range, 4-59%; CD4+, median 34%, range, 20-53%). NKG2D-CAR T cell products contained a higher proportion of CM cells (CD4, p=0.002; CD8, p=0.0005) and lower proportion of EM cells (CD4, p=0.002; CD8, p=0.005) than did Mock-cultured CD4 or CD8 T cells. There were no differences in Temra content (CD4, p=0.6; CD8, p=0.2), and naïve T cells were significantly higher in NKG2D-CAR products (CD4; p=0.002; CD8, p=0.02). Thus, NKG2D transduction yielded a “less differentiated” product than did Mock treatment (Mock CD8+ EM median 82%; Mock CD4+ EM median 74%) (Fig. 4B). Mock-treated cultures had significantly more median TNC and CD3 fold-expansion between Days −6 and 0 than did NKG2D-transduced cultures (30 vs 2, p=0.002); 61 vs 8, p=0.001), which may account for the more differentiated phenotype after mock culture.

Figure 4.

Transduction efficiency, phenotype and functional activity of AML and MM-derived NKG2D CAR-transduced T-cell products in clinical trial. (A) Transduction efficiency in products derived from AML (n=7) and MM patients (n=5). (B) Median distribution of differentiation stages by CD45RO and CCR7 expression on Mock-treated and NKG2D CAR-transduced CD4+ (left panel) and CD8+ (right panel) T cells. Naïve: CD45RO− CCR7+; Central Memory (CM): CD45RO+ CCR7+; Effector Memory (EM): CD45RO+ CCR7−; Terminal Effector Memory RA (Temra): CD45RO− CCR7−; (C) IFN-γ production by ELISA of NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells in response to ligand-positive cells (RPMI 8866, Panc-1 and K562 cells) from a representative AML (top panel) and MM patient (bottom panel); P815 cells (ligand negative); or NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells alone. NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells were incubated with blocking Abs (open bars) or control IgG Abs (closed bars). Error bars represent SD of triplicate wells within a single assay. (D) Stability of 5 NKG2D CAR-transduced products based on lymphocyte viability by 7-AAD exclusion (left panel) and vector-specific NKG2D CAR expression on CD8+ T cells (right panel). * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; n.s indicates not significant, p≥ 0.05.

The culture was still very dynamic at the time of harvest. When looking at all cell events based on size and density profile by FACS (i.e., forward scatter (FSC) and size scatter (SSC)), many granulocytes were still present. However, these granulocytes were primarily 7-AAD positive and in the process of undergoing apoptosis: median 7-AAD negative granulocytes 18%, range, 8-50% (Table 2B). In contrast, cells within the lymphocyte/monocyte gate based on FSC and SSC parameters were median 98% 7-AAD negative, range, 91-100%. When gating only on the 7-AAD negative, live fraction, there were low frequencies of CD19+, CD33+/CD11b+ and CD14+ cells, representing B, myeloid and monocytic cells, respectively. Of all these non-T cell populations, only CD19+ B cells were seen to have any notable survival at the end of patient’s culture, i.e., one product with 16.7% CD19+ B cells (Mock culture, 9.7% B cells), and all others <0.3%.

In terms of tumor-cell carryover, this manufacturing process was highly efficient at elimination of myeloid cells, including immature CD34+ cells, and plasma cells. Median percentage of CD34+ cells, as a surrogate blast marker, in AML patients was 0.1% (range, <0.1 – 6%) at harvest on day 0 compared to 32% (range, 1 – 84%) at collection on Day −8. For the MM patients, the median frequency levels of CD38+/CD138+/CD3-plasma cells were very low to begin with at 0.3% (range, <0.1 – 2%) and remained low at Day 0.

To confirm functional activity of the clinical product, NKG2D CAR-transduced T-cell products from 4 patients (3 AML and 1 MM) were co-cultured with NKG2D-ligand positive human tumor cell lines RPMI 8866, Panc-1, and K562 (Fig. 4C). NKG2D CAR T cells secreted high levels of IFN-γ when cultured with ligand-positive cells, which was significantly inhibited by addition of NKG2D blocking Abs (AML Pt, p=0.0001, 0.0007, 0.01; MM Pt, p<0.0001, 0.001, 0.009, respectively).

NKG2D CAR T-cell product release and stability

Each NKG2D CAR T-cell product was infused fresh rather than cryopreserved. To meet regulatory specifications (acceptable thresholds in parentheses), samples were collected from NKG2D CAR T-cells culture at Day −1 and evaluated by PCR for presence of mycoplasma (undetectable), replication competent retrovirus (RCR) (undetectable) and vector copy number (VCN) (≤ 5 copies/cell). A second stage of release studies, performed on Day 0, included measurement of endotoxin levels (≤5 EU/kg/hr) and a Gram stain (no organisms seen) to ensure no bacterial contamination. The certificate of analysis of the final product for infusion also contained Day 0 trypan blue viability of all harvested cells (≥70%) and transduction efficiency on CD8+ cells (≥ 5% vector-specific NKG2D expression) (Supplemental Table 2). NKG2D CAR T cells were dosed on total viable CD3+ T cells. Cultures for bacterial sterility were obtained at harvest and maintained for 14 days but were not available at release. All T-cell products in GMP validations (n=5) and the clinical trial (n=12) passed all release criteria, including 14-day sterilities (Supplemental Table 2).

Lastly, we determined the stability of the product to establish an expiration time and allow flexibility in infusion time based on clinical conditions. Harvested NKG2D CAR T-cell products (n=5) were placed at 4°C and tested after 24 and 48 hours for cell viability, cytokine secretion, transduction efficiency and expression of T-cell markers (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Table 3). There was no significant change in the % Trypan blue viability of all cells (p= 0.09), 7-AAD-based viability of lymphocytes (p=0.68), % CD8 among lymphocytes (p=0.83), CD8+ vector-specific NKG2D expression (p=0.99) or functional activity by IFN-γ production (p=0.72) at 48hrs.

Discussion

An increasing number of studies describe the use of autologous CAR T cells to treat many types of tumors [11, 12]. CAR T cells as a treatment for patients with B-cell malignancies have been most extensively investigated, with very impressive response rates [13–15], and with selected products recently approved by FDA (Kymriah™ and Yescarta™). However, myeloid diseases and solid tumors have been much harder to target given lack of antigens specific to tumor cells and not on healthy tissues. Therefore, we present data on a non-canonical CAR incorporating the NKG2D activating receptor which can recognize multiple NKG2D ligands upregulated by the process of malignant transformation across a wide range of human cancer types, including AML/MDS and myeloma. Given the novelty of this CAR target and the importance of manufacturing conditions in final product composition, clinical efficacy, and toxicity, we have thoroughly detailed our manufacturing steps and product characteristics to augment the clinical results of the first-in-human Phase I clinical trial utilizing these products. We demonstrate feasibility of manufacturing autologous T cells expressing NKG2D CAR T cells using a 9-day process of activation with soluble anti-CD3 antibody and rhIL-2, two rounds of retroviral transduction with an SFG-NKG2D-CD3ζ vector, and expansion with rhIL-2 in G-Rex flasks. Successful manufacturing was noted with both research-grade and GMP-grade reagents and vector; in 20 healthy donor samples, 6 samples from donors with malignancies and then 7 patients with AML/MDS and 5 with MM in a therapeutic clinical trial. We stress the reproducibility of our process, as manufacturing failures present an important limitation for this cost-intensive class of cell therapies [16–19].

Without CD3+ T or T-cell subset selection, we found virtually no carryover of immature myeloid cells or plasma cells, little carryover of live myeloid or monocytic cells based on CD13/CD33 and CD14 markers, and only 1 case of notable B-cell survival into the harvested product. The relatively short manufacturing process likely accounts for some residual carryover of non-CAR cells, and elutriation or selection steps could be considered in future studies to enhance purity. CD4 and CD8 composition of the final T-cell product varied widely between patients, potentially impacted by prior disease-directed therapy, with a predominance of effector memory and central memory T cells at harvest. A median of 66% and 93% vector-specific NKG2D CAR surface expression was seen on CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively. Every pre-clinical and clinical product tested showed IFN-γ secretion against NKG2D-ligand positive cell lines that was specifically inhibited by NKG2D-blocking antibodies. In 3 healthy donor products, additional inflammatory cytokines (GM-CSF, TNFα, and RANTES) were preferentially produced by NKG2D-transduced versus Mock T cells, while inhibitory cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-10 were produced at lower levels. All clinical products passed release criteria based on viability, VCN, RCR and bacterial testing.

Regarding unique aspects of processing, we stimulated cells with OKT3 and rhIL-2 with minimal expansion during stimulation but excellent subsequent transduction efficiency. Between the first transduction and harvesting, we had median 8-fold, up to 54-fold expansion of CD3+ T cells. Our results are in line with data from other trials indicating that stimulation of T cells using soluble anti-CD3 antibody and rhIL-2 results in consistent expansion and functional activity of the CAR T cells [14, 20, 21]. We released and infused the fresh product within 9 days of apheresis. This required sampling for VCN, RCR and mycoplasma 24 hours prior to final harvest with exquisite communication and coordination but should be considered as a way to decrease manufacturing time, which is crucial for patients with active disease. Although, the DAP10 costimulatory gene was not included in the NKG2D-CD3ζ fusion or vector, expression of NKG2D on the cell surface requires this chaperone protein. Therefore, DAP10 was clearly natively expressed and colocalized with the CAR, creating a functional second generation CAR [22].

In terms of future optimization, in this early-stage trial requiring cell doses of only 1×106 to 3×107, we achieved sufficient cell numbers starting from peripheral blood draws of 200mL from patients with ALCs as low as 110/uL, and when T cells comprised less than 3% of all cells plated at Day −8. However, for higher dose-escalations, scalability will need to be addressed, perhaps by utilizing exclusively apheresis products, performing retroviral transduction in bags (validations successfully performed but not shown), and large-scale expansion systems such as larger G-Rex containers, or WAVE™ bioreactors [23, 24]. Additionally, a multicenter trial may require cryopreservation of the final product. We validated stability of multiple aspects of the final product for 48 hours. However, optimal conditions for cryopreservation, thawing and cell recovery should be further explored.

There are several potential limitations of the current manufacturing approach

While production was uniformly successful, expansion of T cells ranged from 2 to 54-fold after transduction, CD4 and CD8 composition was highly variable, and CD8+ transduction efficiency ranged from 15-87%, possibly due to patient age, prior regimens and type and stage of disease, as have been previously observed by other studies [25, 26]. Future approaches might involve T-cell selection strategies to limit transduction and/or reinfusion of B- or myeloid cells and dosing based on CAR+ T cells rather than viable T cells. Efforts are underway to establish monoclonal antibodies to the NKG2D/CD3ζ fusion region to facilitate more accurate detection of NKG2D-CAR expression. Our process yielded EM T cells, associated with anti-tumor activity in vitro and sizable percentages of CM cells, associated with persistence. Although optimal composition for efficacy and resistance to suppression within the tumor microenvironment is unknown, an approach to optimize percentage of a younger memory population, such as T stem cell memory cells could be contemplated in future approaches [27–30]. Preclinical studies demonstrated NKG2D CAR T cells promote changes in the microenvironment that lead to an overall improvement of anti-tumor response in multiple animal models [31, 32]. What aspects of manufacturing and product composition are critical to achieving this effect in humans remains to be elucidated.

In summary, this study demonstrated feasible generation of sufficient numbers of functional NKG2D CAR-transduced T cells in a short period of time, although product composition and degree of expansion was highly variable. The manufacturing process described here allows for a great level of flexibility and can be easily scaled and adapted for future novel NKG2D CAR T-cell trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Institutes of Health Grant R44 HL099217 and the Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation COE grant for supporting this work. We also thank the DartLab Immunoassay and Flow Cytometry Shared Resource at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth for their services with Luminex analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

C.L.S. has patents and financial interests in NK receptor–based CAR therapies. C.L.S. is a scientific founder for Celdara Medical, a consultant, and receives research support from Celdara Medical. These conflicts are managed under the policies of Dartmouth College. M.-L.S. has an immediate family member with financial interests in NK receptor–based CAR therapies. J.M.M., J.R., M.W.F., T.W., and A.S. are employed by Celdara Medical, which has a material financial interest in NK receptor–based CAR intellectual property assigned to the Trustees of Dartmouth College. DEG, SS and FLE are employees of Celyad S.A, which is the clinical trial sponsor. G.D. is currently an employee of Novartis, which has material financial interests in other CAR T cell therapies. S.B., S.N. received salary support through an SBIR grant awarded to Celdara Medical. The other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national regulatory committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Gacerez AT, Arellano B, Sentman CL. How Chimeric Antigen Receptor Design Affects Adoptive T Cell Therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(12):2590–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava S, Riddell SR. Engineering CAR-T cells: Design concepts. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(8):494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dotti G, Gottschalk S, Savoldo B, Brenner MK. Design and development of therapies using chimeric antigen receptor-expressing T cells. Immunol Rev. 2014;257(1):107–26. doi: 10.1111/imr.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Riviere I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(4):388–98. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Ye ZL, Yuan ZG, Luo ZQ, Jin HJ, Qian QJ. New Strategies for the Treatment of Solid Tumors with CAR-T Cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12(6):718–29. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newick K, Moon E, Albelda SM. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for solid tumors. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016;3:16006. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldhauer I, Steinle A. NK cells and cancer immunosurveillance. Oncogene. 2008;27(45):5932–43. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spear P, Wu MR, Sentman ML, Sentman CL. NKG2D ligands as therapeutic targets. Cancer immunity. 2013;13:8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sentman CL, Meehan KR. NKG2D CARs as cell therapy for cancer. Cancer J. 2014;20(2):156–9. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang T, Lemoi BA, Sentman CL. Chimeric NK-receptor-bearing T cells mediate antitumor immunotherapy. Blood. 2005;106(5):1544–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almasbak H, Aarvak T, Vemuri MC. CAR T Cell Therapy: A Game Changer in Cancer Treatment. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:5474602. doi: 10.1155/2016/5474602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jena B, Moyes JS, Huls H, Cooper LJ. Driving CAR-based T-cell therapy to success. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2014;9(1):50–6. doi: 10.1007/s11899-013-0197-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2014;123(17):2625–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-492231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN, Steinberg SM, Stroncek D, Tschernia N, Yuan C, Zhang H, Zhang L, Rosenberg SA, Wayne AS, Mackall CL. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):517–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, Mahnke YD, Melenhorst JJ, Rheingold SR, Shen A, Teachey DT, Levine BL, June CH, Porter DL, Grupp SA. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter DL, Hwang WT, Frey NV, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, Loren AW, Bagg A, Marcucci KT, Shen A, Gonzalez V, Ambrose D, Grupp SA, Chew A, Zheng Z, Milone MC, Levine BL, Melenhorst JJ, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(303):303ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, Chung SS, Stefanski J, Borquez-Ojeda O, Olszewska M, Qu J, Wasielewska T, He Q, Fink M, Shinglot H, Youssif M, Satter M, Wang Y, Hosey J, Quintanilla H, Halton E, Bernal Y, Bouhassira DC, Arcila ME, Gonen M, Roboz GJ, Maslak P, Douer D, Frattini MG, Giralt S, Sadelain M, Brentjens R. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science translational medicine. 2014;6(224):224ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torikai H, Cooper LJ. Translational Implications for Off-the-shelf Immune Cells Expressing Chimeric Antigen Receptors. Mol Ther. 2016;24(7):1178–86. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie DS, Neeson PJ, Khot A, Peinert S, Tai T, Tainton K, Chen K, Shin M, Wall DM, Honemann D, Gambell P, Westerman DA, Haurat J, Westwood JA, Scott AM, Kravets L, Dickinson M, Trapani JA, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Prince HM. Persistence and efficacy of second generation CAR T cell against the LeY antigen in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Ther. 2013;21(11):2122–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brudno JN, Somerville RP, Shi V, Rose JJ, Halverson DC, Fowler DH, Gea-Banacloche JC, Pavletic SZ, Hickstein DD, Lu TL, Feldman SA, Iwamoto AT, Kurlander R, Maric I, Goy A, Hansen BG, Wilder JS, Blacklock-Schuver B, Hakim FT, Rosenberg SA, Gress RE, Kochenderfer JN. Allogeneic T Cells That Express an Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Induce Remissions of B-Cell Malignancies That Progress After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation Without Causing Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(10):1112–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, Dudley ME, Stetler-Stevenson M, Feldman SA, Maric I, Raffeld M, Nathan DA, Lanier BJ, Morgan RA, Rosenberg SA. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116(20):4099–102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber A, Sentman CL. NKG2D receptor regulates human effector T-cell cytokine production. Blood. 2011;117(24):6571–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajgain P, Mucharla R, Wilson J, Welch D, Anurathapan U, Liang B, Lu X, Ripple K, Centanni JM, Hall C, Hsu D, Couture LA, Gupta S, Gee AP, Heslop HE, Leen AM, Rooney CM, Vera JF. Optimizing the production of suspension cells using the G-Rex “M” series. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2014;1:14015. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2014.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Riviere I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016;3:16015. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollyman D, Stefanski J, Przybylowski M, Bartido S, Borquez-Ojeda O, Taylor C, Yeh R, Capacio V, Olszewska M, Hosey J, Sadelain M, Brentjens RJ, Riviere I. Manufacturing validation of biologically functional T cells targeted to CD19 antigen for autologous adoptive cell therapy. Journal of immunotherapy. 2009;32(2):169–80. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318194a6e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh N, Perazzelli J, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Early memory phenotypes drive T cell proliferation in patients with pediatric malignancies. Science translational medicine. 2016;8(320):320ra3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas SN. Committing CAR T cells to memory. Science translational medicine. 2016;8(370):370ec205. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kueberuwa G, Gornall H, Alcantar-Orozco EM, Bouvier D, Kapacee ZA, Hawkins RE, Gilham DE. CCR7+ selected gene-modified T cells maintain a central memory phenotype and display enhanced persistence in peripheral blood in vivo. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. Sorting through subsets: which T-cell populations mediate highly effective adoptive immunotherapy? Journal of immunotherapy. 2012;35(9):651–60. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31827806e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golubovskaya V, Wu L. Different Subsets of T Cells, Memory, Effector Functions, and CAR-T Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2016;8(3) doi: 10.3390/cancers8030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spear P, Barber A, Sentman CL. Collaboration of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) -expressing T cells and host T cells for optimal elimination of established ovarian tumors. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(4):e23564. doi: 10.4161/onci.23564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spear P, Barber A, Rynda-Apple A, Sentman CL. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells shape myeloid cell function within the tumor microenvironment through IFN-gamma and GM-CSF. J Immunol. 2012;188(12):6389–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.