Abstract

Background

South Africa’s public healthcare system is better equipped to manage breast cancer than most other SSA countries, but survival rates are unknown.

Methods

A historical cohort of 602 women newly diagnosed with invasive breast carcinoma during 2009–2011 at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, Soweto, Johannesburg, was followed using health systems data to December 2014. ‘Overall survival’ time was defined from diagnosis to death or terminal illness. Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) associated with woman and tumour characteristics.

Results

During a median 2.1 years follow-up (IQR 0.5–3.8), 149 women died or were classified terminally ill; 287 were lost-to-follow-up. 3-year survival was 84% for early stage (I/II) and 56% for late stage (III/IV) tumours (late v early: HR 2.8 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.9–4.1), however the 42% cumulative losses to follow-up over this period were greater for late stage, half of which occurred within 6 months of diagnosis. After mutual adjustment for stage, grade, age, receptor subtype and HIV status, lower survival was also associated with triple negative (HR 3.1 (95% CI: 1.9–5.0)) and HER2-enriched (2.5 (95% CI: 1.4–4.5)) compared to ER/PR+ HER2− tumours, but not with age or HIV-infection (1.4 (95% CI: 0.8, 2.3)).

Conclusion

In this South African cohort, breast cancer survival is suboptimal, but was better for early stage and hormone receptor-positive tumours. Efforts to reduce clinic losses in the immediate post-diagnosis period, in addition to early presentation and accelerated diagnosis and treatment, are needed to prevent breast cancer deaths, and survival improvements need to be monitored using prospective studies with active follow-up.

Keywords: South Africa, Survival, Breast neoplasms, Stage at diagnosis, Historical cohort

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Despite lower incidence rates of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) compared to high income countries (HICs), mortality rates from breast cancer are similar in the two regions because of poorer outcomes in the former. Several studies have shown 5-year survival estimates in SSA to be approximately 50% [1–6] compared to 90% in the USA for women diagnosed with breast cancer during 2006–12 [7]. Although a limited number of breast cancer survival studies have been conducted in SSA, considerable variation is expected between the countries within this region.

The South African public healthcare system is considerably more advanced and equipped to manage breast cancer than most other SSA countries [8]. Availability of treatment is better and barriers to diagnosis and treatment are relatively fewer. Notably, South Africa has an extensive private and public hospital network; multiple tertiary hospitals equipped with specialized cancer treatment facilities; the highest number of radiotherapy machines per cancer patient in SSA [9]; and a standardized national public health laboratory system that supports histopathological diagnosis and routine receptor determination to aid therapeutic decisions [10].

In South Africa, as in other SSA countries, there is limited opportunistic and no population-wide breast cancer screening, thus tumour stage at first presentation is typically more advanced compared to HIC settings, but it may be more favourable than in other SSA settings [11;12]. Whilst the aforementioned factors would be expected to lead to improved survival in South Africa compared to other SSA countries, the complexities of cancer treatment are challenging [13] and it is unclear how the relatively high proportion of HIV-positive breast cancer patients in this setting (15–20%) affect survival [14;15]. Further, because resource-limited settings tend to have large losses to follow-up due to various factors including poor healthcare information systems [16], most breast cancer survival estimates from SSA have large uncertainty margins and might be biased.

The Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, Johannesburg, is South Africa’s largest government hospital providing tertiary care to the 3–4 million population of Soweto and surrounding areas in Gauteng Province. CHBAH initiated a dedicated breast clinic around 2001 which provides surgical treatment as well as patient follow-up, and systematically uses an electronic clinic database to aid clinical management. This database records all patient contacts, including treatments and, ideally, 6-monthly check-ups, for at least 5 years post-diagnosis. Medical and radiation oncology treatment is provided at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH), a tertiary/quaternary hospital 18 km from CHBAH. Our previous articles describe key clinical characteristics, including an encouraging trend towards earlier presentation between 2006–12, a predominance of ER-positive disease and a considerable (17%) proportion of HIV-positive breast cancer patients [11;14;17]. In the present study, we aimed to estimate breast cancer survival using this unique resource, by assembling a historical cohort of women diagnosed during 2009–2011 at CHBAH. We also assessed the accrual of losses-to-follow-up because, using recent terminology [16], the use of ‘ambient’ data means such losses can be substantial and may cloud ‘nominal’ survival estimates.

2.0 METHODS

2.1 Breast cancer patient cohort

In 2006, a patient management database was initiated at the CHBAH breast clinic, containing clinico-diagnostic and demographic factors. In early 2015, we assembled a historical cohort comprising women newly diagnosed with invasive, histologically-confirmed, primary breast carcinoma (ICD10 C50) at the CHBAH between 01 January 2009 and 31 December 2011. This diagnostic period was chosen because it allowed for a potential follow-up period of at least 3 years (to end of 2014) for all women. In our setting, diagnosis of breast cancer during this time period entailed referral or presentation to the CHBAH breast clinic; a triple assessment comprising (i) clinical examination and staging, (ii) imaging with mammography and ultrasonography and (iii) an image-guided core needle biopsy for histological diagnostic confirmation, tumour grade and receptor subtyping performed by the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) laboratory. Neither Ki-67 mitotic index testing nor FISH testing for equivocal HER2 results were routinely available during this period. Two to three weeks after presentation, when pathology reports were available, women were informed of their diagnosis and treatment plans were outlined. The initial treatment period typically involved surgery, surveillance and, when necessary, palliative care at CHBAH, and chemotherapy and radiotherapy at CMJAH. After completing treatment, follow-up visits were scheduled at 6-monthly intervals for the first 2–3 years, and at times were duplicated between departments involved in treatment at both CMJAH and CHBAH. A small number (n=13, 2%) of women did not return for their diagnostic results and were not included in this analysis.

2.2 Follow-up and outcomes

We aimed to perform an analysis of overall survival amongst the breast cancer cohort. For this purpose, follow-up commenced on the date of breast cancer diagnosis, which for each woman was defined as the earliest of: histological confirmation of breast cancer, treatment decision meeting date, or, if the previous two were missing, date of first breast cancer treatment. Thereafter, follow-up of women and outcomes were based on ‘ambient’ data, that is, medical records routinely available in all treatment departments and hospital records of admissions or the hospital register of deaths. Prior to this study, these data were not routinely integrated thus the status of each cohort member during follow-up period was searched for in these records from both CHBAH and CMJAH. Survival time from diagnosis to death was the “ideal” outcome of interest, thus we initially ascertained whether there was any indication of death and the date thereof. For patients without such an indication, disease status at the time of last contact was determined from medical records as: (i) alive (specified as no evidence of disease; with stable disease; with disease progression; or alive but disease status unknown) or (ii) had terminal disease, was unlikely to survive more than 3 months and was receiving end-of-life care. The latter status was determined by a record review of all patients included in the study by senior clinicians and was included because, in this setting, many terminal patients do not die in the hospital, but rather in their own homes, supported by the CHBAH mobile palliative care team if they live in the nearby vicinity. Other urban South African cohorts have reported a similar end-of-life situation [18]. In the present study, there were as many patients who were considered terminal as there were patients known to have died. As we did not have permission to follow up beyond ambient data, we analysed the combined endpoint of time-to-terminal-illness or death as the best estimate of overall survival.

2.3 Prognostic indicators

Clinical staging information (AJCC and TNM), histology type, the Scarff-Bloom Richardson tumour grade (1=well, 2=moderate or 3=poorly differentiated) and immunohistochemically-determined oestrogen (ER), progesterone (PR) and HER2 receptor status was collected on tumour specimens. For this study, cut-offs of >1% (score 1, 2 or 3) were considered ER-positive and PR-positive while for HER2 status, immunohistochemical scores of 0, 1 and 2 were considered HER2-negative and score 3 as HER2-positive. During the period of this study, HIV testing following informed consent was encouraged, particularly in younger patients. Previous studies have shown the HIV-prevalence within this cohort to be similar to that of the catchment population [14] Standard policy is to refer all HIV-positive patients for antiretroviral (ARV) therapy prior to starting chemotherapy.

2.4 Ethics approval

The study was approved by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Ethics Committee (IEC14-14) and the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M130369/M110562). Record retrieval was approved by the CEOs of CHBAH and CMJAH (11 June 2013). Individual consent from women was not required as this was a retrospectively designed study, thus analyses were based on existing data only.

2.5 Statistical methods

We performed a survival analysis of time from breast cancer diagnosis (time zero) to terminal illness or death, with these dates and events as defined above. Women were censored on the date when they were last known to be alive, or on 31st December 2014 (the administrative censoring date after which data extraction began) giving a potential maximum follow-up time of 3 years for women diagnosed at the end of 2011, and 6 years for those diagnosed in early 2009. Women were considered as lost to follow-up if they were censored prior to the administrative censoring date. We generated Kaplan-Meier curves for terminal illness-free survival, and, assuming that losses to follow-up were uninformative, Cox regression models to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) of terminal illness/death associated with each risk factor. Crude HRs were first estimated for all factors, and thereafter mutually adjusted for age (continuous), AJCC stage (4 categories), tumour grade (3 categories), HIV status (positive, negative and unknown) and receptor subtype (ER/PR/HER2 combined), except for ER status which was adjusted for age, stage, grade and HIV status. Proportional hazards assumptions were assessed through inclusion of interaction terms with number of years since diagnosis.

Given the reliance on ambient data, we examined the incidence proportion of losses to follow-up using the Aalen-Johansen estimator, which accounts for the competing events of terminal illness/death [19]. Further, because these losses to follow-up were sizeable and increased with time-since-diagnosis, we performed a Lexis expansion of the follow-up time at 2 years and at 4 years, and then estimated HRs based on follow-up to 2 and to 4-years. Lastly, because many losses occurred within the first few months of diagnosis, we calculated conditional survival estimates, conditional on the patient being alive for at least 6 months. All analyses were conducted in STATA using the stset suite of commands.

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of breast cancer cohort

During 2009–2011, 602 women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer at CHBAH, with a mean age at diagnosis of 54.4 years (SD 14.2 years). Table 1 shows brief demographic, tumour and treatment characteristics. The vast majority (91%) were black women; and HIV status was classified as unknown (17%), negative (68%) or positive (15%). Overall, 7 (1.2%) patients had synchronous bilateral tumours; 31 (5%) women were diagnosed at stage I, 276 (46%) at stage II, 245 (41%) at stage III and 50 (8%) at stage IV. 392 (65%) of tumours were ER/PR-positive, 69 (11.5%) were HER2-enriched and 126 (22%) were triple negative. During follow-up, most women (89%) received at least one form of surgical, chemo, radiation or endocrine therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 602 women diagnosed with breast cancer at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, South Africa, from 2009 to 2011

| All (n=602*) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics: | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years, mean ± SD): | 54.4 ± 14.2 | |

| | | |

| Race (%): | Black: | 542 (90.8%) |

| White: | 22 (3.7%) | |

| Mixed ancestry: | 19 (3.2%) | |

| Indian/Asian: | 14 (2.4%) | |

| | | |

| HIV status (%): | Positive: | 88 (14.6%) |

| Negative: | 411 (68.3%) | |

| Unknown: | 103 (17.1%) | |

| | | |

| Median follow-up time (IQR) years: | 2.1 (0.5 – 3.8) | |

| | | |

| No record of treatment (%): | 67 (11.1%) | |

| Had surgery (%): | 446 (74.1%) | |

| Initiated chemotherapy (%): | 406 (67.4%) | |

| Initiated radiation therapy (%): | 314 (52.2%) | |

| Initiated endocrine treatment (%): | 277 (46.4%) | |

| | | |

| Tumour Characteristics: | ||

| Stage (%): | I | 31 (5.2%) |

| II | 276 (45.9%) | |

| III | 245 (40.7%) | |

| IV | 50 (8.3%) | |

| | | |

| Grade (%): | 1 | 62 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 270 (49.2%) | |

| 3 | 217 (39.5%) | |

| | | |

| ER status (%): | Positive | 367 (62.3%) |

| Negative | 222 (37.7%) | |

| PR status (%): | Positive | 314 (53.5%) |

| Negative | 273 (46.5%) | |

| HER2 status (%): | Positive | 141 (24.2%) |

| Negative | 442 (75.8%) | |

| | | |

| Receptor subtype (%): | ER+/PR+; HER2− | 315 (54.2%) |

| ER+/PR+; HER2+ | 71 (12.2%) | |

| ER− & PR−; HER2+ | 69 (11.9%) | |

| ER− & PR−; HER2− | 126 (21.7%) | |

| | | |

Missing data were n=5 (1%) for race; n=53 (9%) for grade; n=13 (2%) for ER status; n=15 (3%) for PR status; n=19 (3%) for HER2 status; n=21 (4%) for receptor subtype.

3.2 Overall survival and losses to follow-up

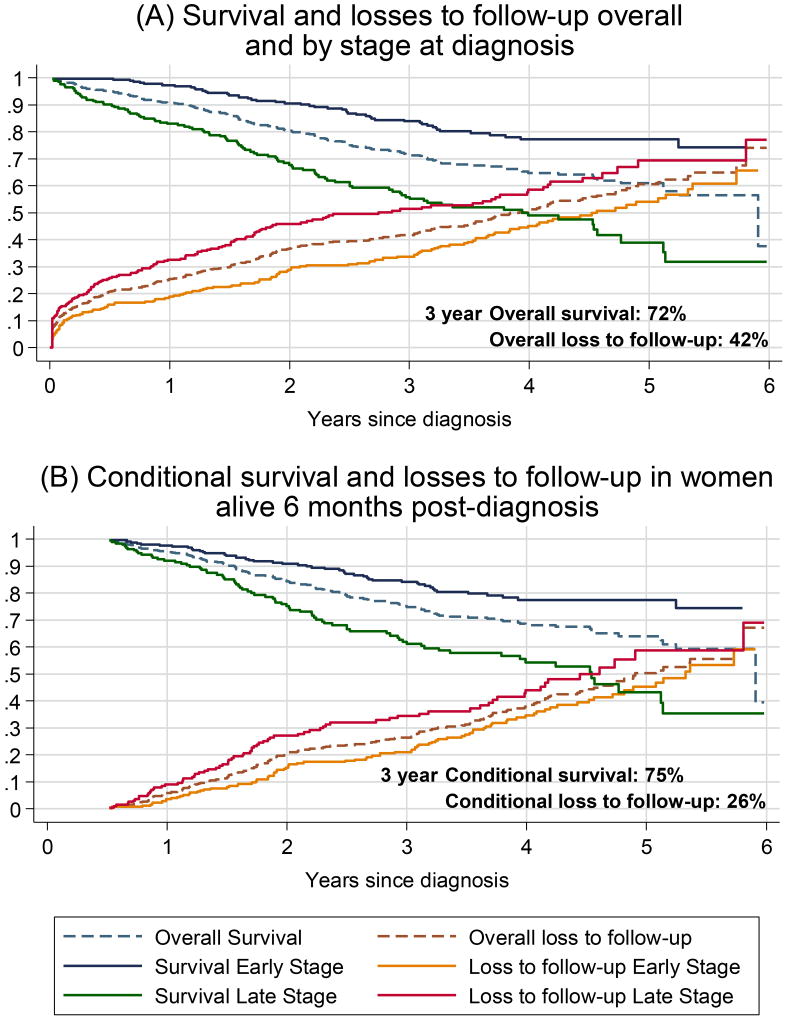

The median follow-up time was 2.1 years (IQR 0.5–3.8, range 1 week to 6 years), during which time 149 women (24.8% of the initial cohort) either died (n=74; 12.3%) or were determined to be terminally ill (n=75; 12.5%). Of the deaths, 62 were recorded as having died from breast cancer, 9 of unknown cause, and 3 of other causes. By the end of 2014, a total of 287 (48%) women were lost to follow-up. Sixty nine women (12%) were lost to follow-up within the first 30 days of their breast cancer diagnosis and a cumulative total of 123 (20%) were lost to follow-up within the first 6 months of diagnosis. These considerable losses are shown in Figure 1A, which plots the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of terminal disease-free survival alongside the cumulative proportion of losses-to-follow up, overall and separately for women diagnosed with early (stage I/II) and late stage (III/IV) cancers.

Figure 1.

Terminal illness-free survival and cumulative incidence of loss to follow-up after breast cancer diagnosis at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, overall and by stage at diagnosis for (A) 602 breast cancer patients diagnosed 2009–2011 and (B) conditional estimates for 454 breast cancer patients known to be alive 6 months post diagnosis. As losses to follow-up were more likely to occur in women diagnosed at late stages, the crude overall survival is over-estimated.

The probability of terminal illness-free survival at the CHBAH breast clinic was 91% at 1 year, 80% at 2 years, 72% at 3 years, 65% at 4 years and 61% at 5 years, whilst losses to follow-up were 25% at 1 year, 37% after 2 years, 42% after 3 years, 51% after 4 years and 61% after 5 years. Assuming that, within groups, survival rates among the women who were lost to follow-up do not differ from those followed, 3-year survival was 84% and 56% for early and late stage at diagnosis respectively; however, overall 42% patients had been lost to follow-up by the end of 3 years; 34% and 51% for early and late stage respectively.

Examination of the losses to follow-up over time shows their rapid accumulation in the first few months after diagnosis (Figure 1A) and Table 2 displays the characteristics of women who were lost to follow-up. Throughout, losses to follow-up did not appear to occur randomly; they were more common among women with late stage disease (Table 2, Figure 1); acute losses to follow-up within 6 months post-diagnosis comprised women who had received surgery only or had no record of treatment (54%), as well as older women. Thus, women known to be alive at 6 months and with whom clinicians were in contact form a distinct subcohort, and conditional survival at 6 months becomes a meaningful measure for communication to the in-contact patient population and benefits from being more robust, as subsequent losses to follow-up are an absolute 20 percentage points lower (Figure 1B). Survival to 3 years, conditional on being alive at 6 months, was 84% and 62% for women initially diagnosed with early and late stage breast cancer, respectively while losses-to-follow-up were 21% and 34% respectively at this time point.

Table 2.

Characteristics of women known to be alive at the start of each time interval since diagnosis, and those lost to follow-up within each interval.

| Time since breast cancer diagnosis: | <= 30 days | 1–6 months | 6–12 months | >1 year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women (%): | ||||

| At risk at start of period: | 602 | 528 | 454 | 407 |

| Died or terminal: | 5 (0.8%) | 20 (3.8%) | 21 (4.6%) | 103 (25.3%) |

| Lost to follow-up: | 69 (11.5%) | 54 (10.2%) | 26 (5.7%) | 138 (33.9%) |

| | | | | |

| Median follow-up time (IQR),months, amongst losses: | 0.2 (0.2 – 0.5) | 3.3 (2.0 – 4.5) | 10.2 (8.2 – 10.8) | 28.5 (20.6 – 44.8) |

| | | | | |

| Age at diagnosis for at risk* (mean ± SD): | 54.4 ± 14.2 | 53.5 ± 13.7 | 53.0 ± 13.4 | 53.0 ± 13.7 |

| Age at diagnosis for losses* (mean ± SD): | 60.6 ± 15.7 | 56.4 ± 14.7 | 50.8 ± 9.3 | 53.1 ± 14.9 |

| | | | | |

| % Black among at risk | 542 (90.8%) | 475 (90.7%) | 411 (91.1%) | 370 (91.6%) |

| % Black among losses | 63 (91.3%) | 46 (86.8%) | 23 (88.5%) | 127 (92.7%) |

| | | | | |

| % HIV positive among at risk | 88 (14.6%) | 79 (15.0%) | 67 (14.8%) | 59 (14.5%) |

| % HIV positive among losses | 8 (11.6%) | 8 (14.8%) | 4 (15.4%) | 30 (21.7%) |

| | | | | |

| % Late Stage at diagnosis for at risk: | 295 (49.0%) | 247 (46.8%) | 197 (43.4%) | 165 (40.5%) |

| % Late Stage at diagnosis for losses: | 44 (63.8%) | 30 (55.6%) | 17 (65.4%) | 57 (41.3%) |

| | | | | |

| % received no treatment for at risk: | 67 (11.1%) | 27 (5.1%) | 13 (2.9%) | 10 (2.5%) |

| % received no treatment among losses: | 37 (53.6%) | 5 (9.3%) | 1 (3.9%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| | | | | |

| % had surgery among at risk: | 446 (74.1%) | 421 (79.7%) | 392 (86.3%) | 361 (88.7%) |

| % had surgery among losses | 25 (36.2%) | 28 (51.9%) | 20 (76.9%) | 122 (88.4%) |

| | | | | |

| % initiated chemotherapy among at risk: | 406 (67.4%) | 401 (76.0%) | 367 (80.8%) | 330 (81.1%) |

| % initiated chemotherapy among losses: | 5 (7.3%) | 26 (48.2%) | 21 (80.8%) | 111 (80.4%) |

| | | | | |

| % initiated radiation therapy among at risk: | 314 (52.2%) | 312 (59.1%) | 302 (66.5%) | 275 (67.6%) |

| % initiated radiation therapy among losses: | 0 | 6 (11.1%) | 16 (61.5%) | 90 (65.2%) |

| | | | | |

| % initiated endocrine treatment among at risk: | 277 (46.4%) | 268 (51.2%) | 258 (57.2%) | 249 (61.6%) |

| % initiated endocrine treatment among losses: | 9 (13.0%) | 10 (18.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | 83 (60.6%) |

‘at risk’ refers to patients alive at the start of the time period; ‘losses’ refers to patients lost to follow-up during the time period

3.3 Determinants of terminal illness or death

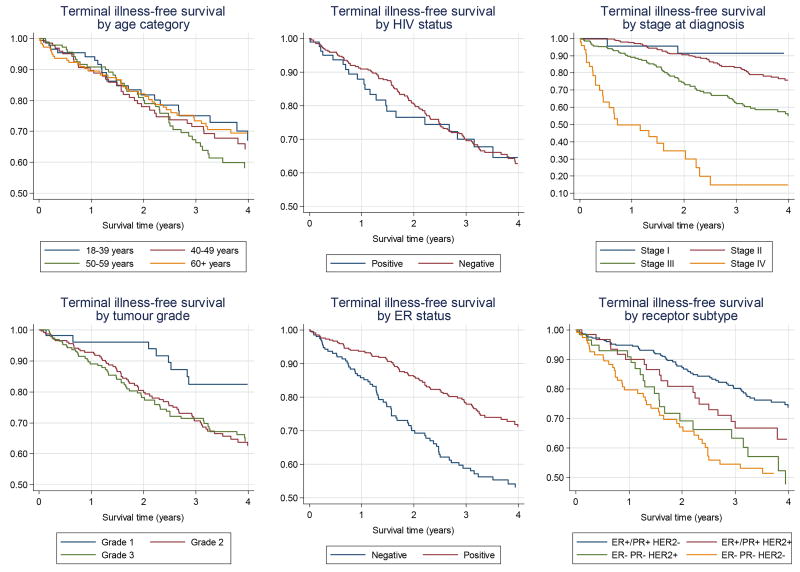

HRs for terminal illness/death were very similar when based on analyses to 4 years or, with fewer losses to follow-up, to 2 years post diagnosis (Table 3), thus Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to 4 years (Figure 2). After mutual adjustment, stage at diagnosis was the strongest risk factor; terminal disease/death rates were 2 and 16 times higher in stage III and IV disease, respectively, than in stage II disease. Women with ER-negative tumours had higher terminal illness/death rates than those with ER-positive tumours (HR 2.5; 95% CI: 1.7–3.7). When analysing all three receptors, compared to women with ER+/PR+ HER2− breast cancer, women with ER+/PR+ HER2+ tumours did not have different rates of terminal illness/death (HR 1.3 (95% CI: 0.7–2.3), whilst women with HER2-enriched and triple negative tumours had significantly increased terminal illness/death rates: HRs of 2.5 (95% CI: 1.4–4.5) and 3.1 (95% CI: 1.9–5.0) respectively. Similar results were seen when the analysis was restricted to those women known to be alive 6 months post-diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3. Hazard ratios for associations between prognostic factors and terminal illness/death after breast cancer diagnosis.

Hazard ratios are presented unadjusted, truncated at 2 and 4 years post-diagnosis, and fully adjusted at 4 years post diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Number of deaths or terminally ill |

Unadjusted, Follow-up to 2 years |

Unadjusted, Follow-up to 4 years |

Adjusted 4 year* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 years |

4 years |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

|

| Age at diagnosis, Years | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 14 | 21 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||

| 40–49 | 24 | 35 | 1.23 (0.63 – 2.37) | 0.544 | 1.16 (0.68 – 2.00) | 0.58 | 0.75 (0.42 – 1.34) | 0.324 |

| 50–59 | 24 | 43 | 1.08 (0.56 – 2.08) | 0.826 | 1.33 (0.79 – 2.24) | 0.285 | 0 .90 (0.50 – 1.62) | 0.735 |

| 60+ | 27 | 41 | 1.04 (0.54 – 1.98) | 0.914 | 1.03 (0.61 – 1.75) | 0.902 | 0.83 (0 .47 – 1.48) | 0.533 |

| Linear trend per 10 years | 1.01 (0.87 – 1.18) | 0.873 | 1.01 (0.99 – 1.15) | 0.826 | 1.01 (0.87 – 1.18) | 0.854 | ||

| HIV Status | ||||||||

| Negative | 62 | 103 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||

| Positive | 16 | 21 | 1.31 (0.76 – 2.28) | 0.330 | 1.09 (0.68 – 1.74) | 0.730 | 1.39 (0.83 – 2.33) | 0.209 |

| Unknown | 11 | 16 | 0.83 (0.44 – 1.58) | 0.570 | 0.67 (0.39 – 1.13) | 0.135 | 0.63 (0.34 – 1.15) | 0.134 |

| Stage at Diagnosis | ||||||||

| I | 2 | 2 | 0.90 (0.21 – 3.86) | 0.891 | 0.39 (0.10 – 1.61) | 0.194 | 0.55 (0.13 – 2.29) | 0.41 |

| II | 21 | 46 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||

| III | 44 | 66 | 3.03 (1.80 – 5.11) | <0.001 | 2.30 (1.58 – 3.36) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.42 – 3.18) | <0.001 |

| IV | 22 | 26 | 14.24 (7.77 – 26.11) | <0.001 | 11.01 (6.71 – 18.05) | <0.001 | 15.92 (8.99 – 28.19) | <0.001 |

| Tumor Grade | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 8 | 0.20 (0.05 – 0.82) | 0.026 | 0.46 (0.22 – 0.95) | 0.036 | 0.50 (0.23 – 1.07) | 0.073 |

| 2 | 40 | 65 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||

| 3 | 37 | 54 | 1.12 (0.71 – 1.75) | 0.626 | 1.00 (0.70 – 1.43) | 0.998 | 0.68 (0.46 – 1.02) | 0.064 |

| ER Status | ||||||||

| Positive | 40 | 71 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref)** | |||

| Negative | 48 | 68 | 2.35 (1.54 – 3.58) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.44 – 2.80) | <0.001 | 2.50 (1.69 – 3.70) | <0.001 |

| Receptor Subtype | ||||||||

| ER+/PR+; HER2− | 31 | 55 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||

| ER+/PR+; HER2+ | 11 | 19 | 1.57 (0.79 – 3.12) | 0.201 | 1.57 (0.93 – 2.64) | 0.091 | 1.25 (0.70 – 2.25) | 0.449 |

| ER− & PR−; HER2+ | 15 | 21 | 2.64 (1.43 – 4.90) | 0.002 | 2.31 (1.40 – 3.83) | 0.001 | 2.53 (1.43 – 4.47) | 0.001 |

| ER− & PR−; HER− | 30 | 41 | 3.07 (1.86 – 5.08) | <0.001 | 2.51 (1.68 – 3.77) | <0.001 | 3.09 (1.93 – 4.96) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, HIV status, stage at diagnosis, grade and receptor subtype.

Adjusted for age, HIV status, stage at diagnosis and grade.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier estimates of terminal illness-free survival for 602 breast cancer patients diagnosed from 2009–11 in Soweto, South Africa, by prognostic factor (unadjusted).

The age of women at diagnosis was not associated with terminal illness/death in this study and nor was race. For the 88 women who were HIV-positive, the rate of terminal illness/death was slightly higher than for HIV-negative women or those with unknown HIV-status, but these differences were not statistically different (Table 3). When restricted to women with known HIV status only, these results remained non-significant (4-year unadjusted HR for HIV-positive women: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.68–1.74). The separation of survival curves between years 1 and 2 (Figure 2) is based on 7 deaths in HIV-positive women resulting in wide confidence intervals.

4.0 DISCUSSION

4.1 Findings

In this study, we examined overall terminal-illness free survival in a historical cohort of 602 women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer during 2009–11, at a tertiary public hospital in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa. The probability of terminal illness-free survival at the CHBAH breast clinic was 91% at 1 year, 80% at 2 years, 72% at 3 years, 65% at 4 years and 61% at 5 years. Losses to follow-up however were extensive, 25% after just 1 year, 37% after 2 years, 42% after 3 years, 51% after 4 years and 61% after 5 years. Assuming a worst case scenario, in which all loses to follow-up were terminal 90 days after their last known contact, 5-year terminal-illness free survival would be only 24%; however, if all patients lost to follow-up were still alive on the date of administrative censoring, 5-year terminal-illness free survival would be 74%. For women who remained in contact with the medical system for at least 6 months, losses to follow-up were fewer (26% at 3 years) thus the 3-year terminal illness-free survival of 75% within this sub-cohort is a more robust measure. Lower survival was associated with late stage tumours, triple negative and HER2-enriched tumours, but not with age at diagnosis or HIV status.

4.2 Comparisons with other studies

Five-year survival rates from breast cancer in low and middle income countries (LMICs) are estimated at 57% [20]. In SSA countries, breast cancer survival estimates are available for Ethiopia, The Gambia, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda [4–6;21–23], and for young patients (<35 years) from Senegal [24]. Comparisons with these studies are hindered by methodological differences and limitations of the individual studies. With the exception of one study in Ethiopia [4], all were retrospective in design and thus losses to follow-up were considerable. At five years, losses to follow-up ranged between 22% and 42%, which are lower than the 61% at five years in the present study. However, losses to follow-up were also dealt with differently: some studies assumed non-informative censoring, others worst-case scenarios, some completely omitted losses from all analyses, while others provided few details. Furthermore, survival endpoints differed. The Ethiopian study assessed metastases-free survival amongst women, staged I–III at diagnosis, to whom tamoxifen was freely supplied where appropriate [4], whereas other studies examined time to death [5;6;21–23]. In the present study, a compromised outcome of terminal disease-free survival was analysed as half of the women with adverse outcomes were classified as terminally ill, without any information on their subsequent (presumed) date of death.

Despite these differences, crude comparisons of survival can be tentatively made. The present study appears to have better 2-year survival (80%) than estimates from Ethiopia and Uganda (~70%) or from Nigeria and young women in Senegal (~60%). Five-year survival in this study (61%) is also higher than in Ethiopia and Uganda (range 46–56%) and considerably better than in Nigeria or the Gambia (12 to 24%) [4–6;21–23]. As previously stated, better survival rates in South Africa were hypothesized and appear to be the case, albeit with the uncertainties mentioned. Beyond SSA, and of interest here, is a USA study which examined breast cancer survival amongst African-American patients with lower socioeconomic status [25], possibly a more similar demographic to the patients attending the CHBAH breast clinic, where 5-year survival was 62%, very similar to the 61% found in our study.

In terms of prognosis, as expected, late stage at diagnosis and intrinsic subtype were significant risk factors for poorer patient outcomes. Associations with late stage had already been established in other SSA studies [4–6;26;27], but this is the first study to robustly establish the 2.5- and 3-fold higher death rates in HER2-enriched and triple negative breast cancers, respectively. Poorer survival among HER2-enriched tumours may be expected, since patients in the public sector do not have access to trastuzumab therapy. International studies have found similar results, and beyond 5 years (a period that could not be observed in our study) HER2-positive, ER-negative tumours may have even lower survival than triple negative tumours [28]. Thus, despite losses to follow-up which render absolute survival estimates uncertain, our findings regarding differences in patient outcomes based on stage and subtype appear to be robust and lend credibility to the lack of differences by age, in contrast to the Ethiopian study [4].

This is the largest study to date examining breast cancer outcomes in HIV-positive women (n=88). We found no evidence of large survival disadvantages in HIV-positive women; a previous Ugandan study, which included 24 HIV-positive breast cancer patients, found increased mortality associated with HIV (HR 2.04 (95% CI 0.76–5.47)), but confidence intervals were wide [29]. Further studies of HIV-positive breast cancer patients, based on a larger size and including wider outcomes are warranted in similar HIV-endemic settings given the high HIV prevalence in younger breast cancer patients.

4.3 Limitations

Cancer survival studies in SSA have all reported large losses to follow-up especially when follow-up methods are passive, as they were in this study. In South Africa, as in many SSA countries, patients diagnosed with terminal illness prefer to return to their homes to die and thus there is no formal record of their deaths within the ambient data [5]. In addition to these limitations, the present study identified a critical period within the first few months of diagnosis when women were lost to follow-up. This period needs to be given attention by clinicians managing patients as such losses to follow-up are likely to include women who don’t receive any treatment. Researchers prospectively examining overall survival may need more intensive, active follow-up methods during this period. A prospective study would also be able to include, and investigate the role of, lifestyle factors known to be associated with breast cancer survival, such as physical activity, smoking and BMI.

Kaplan-Meier analyses are based on non-informative censoring, assuming that all patients lost to follow-up have the same outcome possibilities as those remaining within the cohort [16], which is not very accurate when there are large losses to follow-up. Studies, such as this one, relying on existing records often have incomplete data which leads to an underestimation of the number of deaths and thus an overestimation of survival by as much as 13% [23]. By including those patients diagnosed with terminal illness and receiving end-of-life care into a composite endpoint, we were able to decrease the loss to follow-up proportions. By further analysing a sub-cohort of patients followed up for at least 6 months, we were able to obtain relatively accurate survival estimates. Finally, as this was a retrospective study, few socio-demographic characteristics of women or outcome disparities could be examined. Furthermore, as we were limited to ambient data where time to recurrence was not always systematically recorded, this outcome could not be accurately assessed.

4.4 Public health implications

In LMICs, the breast cancer incidence burden is increasing by up to 5% per year [30], most likely driven by improved reporting, an aging population and by the adoption of more westernised lifestyles including a decrease in fertility and an increase in obesity especially in urban areas [31]. Late diagnosis of breast cancer is one of the main drivers of poor outcomes [23]. Delays in seeking breast cancer treatment and drop outs from treatment have been linked to a lack of breast cancer education and awareness and to social and cultural barriers such as the cost of treatment and the fear of mastectomy and rejection by a partner and/or community [31;32]. Population-wide mammographic screening is not feasible in many LMICs, but knowledge of clinical and self-breast exams can lead to earlier detection of breast cancers [30;33].

Breast cancer down-staging will only be of benefit if appropriate diagnosis and treatment facilities are available [20]. In South Africa, especially in urban areas, patients have access to high quality diagnosis and treatment facilities, including immunohistochemical analysis of tumour receptors, to determine the best course of treatment. Treatments including surgery and radiation therapy, and systemic therapies including chemotherapy and hormonal therapy are available within the public sector and are likely to account partially for the 2 to 3-fold lower death rates associated with early compared to later stage at diagnosis in this study. Down-staging of breast cancers in this setting should be made a priority to prevent avoidable deaths in women with breast cancer.

5.0 CONCLUSION

Qualified by considerable losses to follow-up, terminal-illness free survival from breast cancer in this Sowetan cohort was estimated to be higher than that of many other SSA countries, but still lags behind HICs. Women with breast cancer subtypes associated with a good prognosis in HICs were the majority and had better survival in this cohort, as did those diagnosed with less advanced disease. The realization that survival is substantially improved in early stage tumours shows that survival gains can be achieved through downstaging in the existing system. Furthermore, efforts need to be made to retain older women within the healthcare system and ensure that they receive their prescribed therapies, especially those diagnosed at later stages. Early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer need to be an urgent priority to further prevent breast cancer deaths in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Few studies have examined breast cancer survival in sub-Saharan Africa.

We studied time to death or terminal illness in a historical breast cancer cohort

Despite considerable losses to follow-up, estimated 3-year survival was 72%

Survival was better in early stage and ER-positive tumours

Early diagnosis and treatment has the potential to improve survival in this setting

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported by an AORTIC BIG CAT award and an IARC Return Grant, and was initiated during the tenure of an IARC Postdoctoral Fellowship to C. Dickens partially supported by the European Commission FP7 Marie Curie Actions – People – Co-funding of regional, national and international programmes (COFUND).

The wider team and baseline data collection were supported by NCI-1R01CA192627 (Drs. Jacobson, Joffe, Neugut and Ruff), the South African Medical Research Council /University Witwatersrand Common Epithelial Cancer Research Centre (Dr. Ruff); CANSA South Africa award “Downstaging and improving survival of breast cancer in South Africa” (Dr Cubasch) and the Columbia University – South Africa Training Program for Research on AIDS-related Malignancies (NIH D43CA153715-03).

We are grateful to the assistance of the staff at the CHBAH Batho Pele Breast Clinic, Medical Oncology (Area 495), Radiation Oncology (Area 348), and Dr Evan Shoul and the staff at the HIV clinic at CMJAH.

Authorship Contributions

Herbert Cubasch – conception and design of study, revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript

Caroline Dickens – acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of results, drafting and revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript

Maureen Joffe – conception and design of study, acquisition of data, revision of manuscript

Raquel Duarte – conception and design of study, acquisition of data, revision of manuscript

Nivashni Murugan – acquisition of data

Ming Tsai Chih – acquisition of data

Kiashanee Moodley – acquisition of data

Vinay Sharma – acquisition of data

Oluwatosin Ayeni – acquisition of data

Judith S. Jacobson – conception and design of study, revision of manuscript

Alfred I Neugut – conception and design of study, revision of manuscript

Valerie McCormack – conception and design of study, analysis and interpretation of results, drafting and revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript

Paul Ruff – data acquisition, revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript

Conflict Of Interest Declaration

Conflicts of interest: none

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved either experimental animals or human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Walker AR, Walker BF, Tshabalala EN, Isaacson C, Segal I. Low survival of South African urban black women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1984 Feb;49(2):241–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sankaranarayanan RSR. Cancer Survival in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Central America. IARC Scientific Publication, No 162. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popoola AO, Ogunleye OO, Ibrahmi NA, Omedele FO, Igwila AI. Five year survival of patients with breast cancer at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. J Medicine and Medical Science Research. 2012;1(2):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantelhardt E, Zerche P, Mathewos A, Trocchi P, Addissie A, Aynalem A, Wondemagegnehu T, Ersumo T, Reeler A, Yonas B, Tinsae M, Gemechu T, et al. Breast cancer survival in Ethiopia: A cohort study of 1,070 women. Int J Cancer. 2013 Dec;22 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galukande M, Wabinga H, Mirembe F. Breast cancer survival experiences at a tertiary hospital in sub-Saharan Africa: a cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:220. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0632-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gakwaya A, Kigula-Mugambe JB, Kavuma A, Luwaga A, Fualal J, Jombwe J, Galukande M, Kanyike D. Cancer of the breast: 5-year survival in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. Br J Cancer. 2008 Jul 8;99(1):63–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013, National Cancer Institute. based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. 2015 Jan 1; Available from: URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/

- 8.Mayosi BM, Lawn JE, van Niekerk A, Bradshaw D, Abdool Karim SS, Coovadia HM. Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009. Lancet. 2012 Dec 8;380(9858):2029–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Wahab M, Bourque JM, Pynda Y, Izewska J, Van der Merwe D, Zubizarreta E, Rosenblatt E. Status of radiotherapy resources in Africa: an International Atomic Energy Agency analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013 Apr;14(4):e168–e175. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickens C, Duarte R, Zietsman A, Cubasch H, Kellett P, Schuz J, Kielkowski D, McCormack V. Racial comparison of receptor-defined breast cancer in Southern African women: subtype prevalence and age-incidence analysis of nationwide cancer registry data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2311–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormack VA, Joffe M, van den BE, Broeze N, Dos SSI, Romieu I, Jacobson JS, Neugut AI, Schuz J, Cubasch H. Breast cancer receptor status and stage at diagnosis in over 1,200 consecutive public hospital patients in Soweto, South Africa: a case series. Breast Cancer Res. 2013 Sep 17;15(5):R84. doi: 10.1186/bcr3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jedy-Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo C, Dos-Santos-Silva I. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 Dec;4(12):e923–e935. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30259-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edge J, Buccimazza I, Cubasch H, Panieri E. The challenges of managing breast cancer in the developing world - a perspective from sub-Saharan Africa. S Afr Med J. 2014 May;104(5):377–9. doi: 10.7196/samj.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cubasch H, Joffe M, Hanisch R, Schuz J, Neugut AI, Karstaedt A, Broeze N, van den BE, McCormack V, Jacobson JS. Breast cancer characteristics and HIV among 1,092 women in Soweto, South Africa. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 Jul;140(1):177–86. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2606-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2016 - Statistical release P0302. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman E, Semeere A, Wenger M, Bwana M, Asirwa FC, Busakhala N, Oga E, Jedy-Agba E, Kwaghe V, Iregbu K, Jaquet A, Dabis F, et al. Pitfalls of practicing cancer epidemiology in resource-limited settings: the case of survival and loss to follow-up after a diagnosis of Kaposi's sarcoma in five countries across sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Cancer. 2016 Feb 6;16:65. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickens C, Joffe M, Jacobson J, Venter F, Schuz J, Cubasch H, McCormack V. Stage at breast cancer diagnosis and distance from diagnostic hospital in a peri-urban setting: a South African public hospital case series of over 1000 women. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(9):2173–82. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark SJ, Collinson MA, Kahn K, Drullinger K, TollMan SM. Returning home to die: circular labour migration and mortality in South Africa. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2007 Aug;69:35–44. doi: 10.1080/14034950701355619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, Auerbach AD. A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004 Oct 4;91(7):1229–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yip CH, Buccimazza I, Hartman M, Deo SV, Cheung PS. Improving outcomes in breast cancer for low and middle income countries. World J Surg. 2015 Mar;39(3):686–92. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2859-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makanjuola SB, Popoola AO, Oludara MA. Radiation therapy: a major factor in the five-year survival analysis of women with breast cancer in Lagos, Nigeria. Radiother Oncol. 2014 May;111(2):321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agboola AJ, Musa AA, Wanangwa N, bdel-Fatah T, Nolan CC, Ayoade BA, Oyebadejo TY, Banjo AA, ji-Agboola AM, Rakha EA, Green AR, Ellis IO. Molecular characteristics and prognostic features of breast cancer in Nigerian compared with UK women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 Sep;135(2):555–69. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H, Chen K, Chia KS, Chen JG, Law SC, Ahn YO, Xiang YB, Yeole BB, Shin HR, Shanta V, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2010 Feb;11(2):165–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gueye M, Kane Gueye SM, Ndiaye Gueye MD, Niasse DF, Gassama O, Diallo M, Moreau JC. Breast cancer in women younger than 35 years : features and outcomes in the breast unit at Aristide le Dantec Teaching Hospital, Dakar. Med Sante Trop. 2016 Nov 1;26(4):377–81. doi: 10.1684/mst.2016.0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal H, Callahan CM, Miller KD, Tu W, Loehrer PJ., Sr Are There Differences in Treatment and Survival Between Poor, Older Black and White Women with Breast Cancer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Oct;63(10):2008–13. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odongo J, Makumbi T, Kalungi S, Galukande M. Patient delay factors in women presenting with breast cancer in a low income country. BMC Res Notes. 2015 Sep 22;8:467. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mody GN, Nduaguba A, Ntirenganya F, Riviello R. Characteristics and presentation of patients with breast cancer in Rwanda. Am J Surg. 2013 Apr;205(4):409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006 Jun 7;295(21):2492–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coghill AE, Newcomb PA, Madeleine MM, Richardson BA, Mutyaba I, Okuku F, Phipps W, Wabinga H, Orem J, Casper C. Contribution of HIV infection to mortality among cancer patients in Uganda. AIDS. 2013 Nov 28;27(18):2933–42. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000433236.55937.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson BO, Ilbawi AM, El Saghir NS. Breast cancer in low and middle income countries (LMICs): a shifting tide in global health. Breast J. 2015 Jan;21(1):111–8. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Wood SN, Ansong D, Nyarko K, Wiafe-Addai B, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014 Apr;144(3):467–78. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NA, Muller JM, Pyke CM, Baade PD. The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: an international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012 Jun;36(3):237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving Breast Cancer Control via the Use of Community Health Workers in South Africa: A Critical Review. J Oncol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/150423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.