Abstract

Background:

Herbal products are widely substituting synthetic antimicrobials due to their minimal adverse effects and cost-effectiveness. Murraya koenigii (curry leaf) is an easily available green leafy vegetable, which is known for their antimicrobial, antioxidative, and cytotoxic activity. However, no published literature available evaluates their effectiveness in treating gingival inflammation. This study was aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of M. koenigii mouthwash in reduction of plaque and gingivitis in comparison with commercially available chlorhexidine (CHX) mouthwash.

Materials and Methods:

This single-center, parallel-arm, randomized controlled clinical trial was carried out among individuals reported to the institution. A total of 45 participants with mild-to-moderate gingivitis were selected and divided into three groups. Group A and B participants undergone scaling and were instructed to use M. koenigii and CHX mouthwashes, respectively. Group C participants have received only scaling. All the participants were recalled after 14 days of prescribed mouthwash use and clinical parameters were recorded. One-way analysis of variance test and Student's paired t-test were used for inter- and intra-group comparison of parameters, respectively.

Results:

On intragroup comparison of clinical parameters, all the three groups showed a statistically significant difference with P ≤ 0.05. On pairwise comparison, it showed a significant difference for Group B versus Group C and Group A versus Group C, while between Group A and Group B showed no significant difference.

Conclusion:

M. koenigii mouthwash is equally effective as CHX, in treating plaque-induced gingivitis.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine gluconate, dental plaque index, gingival index, Murraya koenigii

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is the major causative factor of two common oral disease conditions, dental caries and periodontal diseases. Experimental studies have proved that plaque is responsible for the initiation and progression of periodontal diseases and they correlated the amount of plaque accumulation and development of gingivitis.[1,2] Plaque control is considered as the cornerstone of good oral hygiene practice and it includes mechanical and chemical measures. Mechanical plaque control measures include manual or electric toothbrushes, dental floss, wood sticks, and interdental brushes. However, they are failing to deliver ideal degrees of oral health. Even the most meticulous patient may not always be able to completely remove all plaques.[3] A relatively high degree of personal motivation, manual dexterity, and patient's compliance are required to achieve the ideal level of oral hygiene necessary to control bacterial plaque formation.[4] These shortcomings in home care practices shall open the door for alternative measures.

Chemical plaque control forms an ideal adjunct to mechanical therapy in the treatment of gingivitis which can provide additional benefits in maintaining oral hygiene. Several antibacterial chemicals such as chlorhexidine (CHX) have been successfully prescribed in the prevention and treatment of gingivitis.[5] CHX is considered as the gold standard agent for its chemical substantivity and clinical efficacy in chemical plaque control. However, the patient's compliance to CHX is diminished by some side effects; the most important of those are teeth discoloration and alteration of taste.[6] Hence, there is a need of an alternative medicine that could provide a product enmeshed within the traditional Indian setup and should also be safe and economical.

Murraya koenigii (curry leaf) is a green leafy vegetable, which is known for their antimicrobial, antiemetic, antidiabetic, antiulcer, antioxidative, cytotoxic, and phagocytic activity.[7] Chlorophyll component in curry leaves has been reported as an anticariogenic agent and it also helps to reduce halitosis. Experimental studies have shown an effective reduction in levels of halitosis by orally chewing fresh curry leaves for 5 min and rinsing the mouth with water.[8]

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported evaluating the clinical efficacy of M. koenigii as a mouthwash in the treatment of gingivitis. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of 3% M. koenigii mouthwash in the reduction of plaque and gingivitis and to compare with commercially available gold standard 0.2% CHX mouthwash.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This double-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial included a total of 45 participants within the age group of 20–45 years who reported to the outpatient department of periodontics of the institution, from September 2016 to January 2017. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the institution. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: systemically healthy individuals and participants within the age group of 20–45 years, with minimum 20 teeth and with mild-to-moderate gingivitis (gingival index [GI] and plaque index [PI] scores <1). The exclusion criteria for participants were as follows: patients using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics in the past 3 months, those who underwent scaling in the past 6 months, patients with prosthetic or orthodontic appliances, allergy to active ingredients, pregnant or lactating females, smokers, alcoholics and drug abusers, and current users of any mouthrinse for any dental problems.

Of the total 58 individuals examined for eligibility, 45 individuals were selected for the study. The sample size was calculated using G*Power software (Heinrich-Heine-University Dusseldorf) to obtain 80% of statistical power. Using lot method, the individuals were assigned to one of the three groups.

Group A: 15 individuals undergoing scaling and prescribed to use 3% M. koenigii mouthwash for 15 days

Group B: 15 individuals undergoing scaling and prescribed to use 0.2% CHX mouthwash for 15 days

Group C: 15 individuals undergoing scaling only.

A written informed consent was taken from all participants recruited in the study.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ethanolic extracts of M. koenigii was estimated based on an in vitro study conducted by Nithya et al., against the most predominant periodontal pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia, and MIC was estimated as 0.8 mg/ml. Nine serial dilutions of M. koenigii extracts were made as 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mg/ml. To each dilution, specific concentration of cultured microorganism specimens was added and checked for turbidity. Except 0.2 and 0.4 mg/ml of extract, all other dilutions of extracts showed sensitivity against the cultured microorganism specimens. Based on these observations, the concentration of M. koenigii needed for the preparation of mouthwash was calculated as 3 mg/ml (3%).[9]

The preparation of M. koenigii mouthwash was carried out at College of Pharmacy. The fresh curry leaves which are available were dried under the sun for 3–4 days and thereafter crushed to obtain fine powder [Figures 1 and 2]. A total of 135 g of powder was mixed in 4500 ml of distilled water to make the concentration of solution as 3%. The solution was dispensed in conical flasks and kept in rotary shaker at 120 revolutions per minute for 18 h and then filtered [Figures 3 and 4]. To improve patient compliance, 10 mL of glycerine (sweetening agent) and 5 mL of Pudin Hara (flavoring agent) were added.

Figure 1.

The fresh curry leaves

Figure 2.

Curry leaves were dried under the sun and later crushed to get fine powder

Figure 3.

Solution dispensed in conical flasks

Figure 4.

Conical flasks were kept in rotary shaker at 120 revolutions per minute for 18 h

The prepared M. koenigii mouthwashes were dispensed in opaque bottles and were sequentially numbered [Figure 5]. The commercially available 0.2% CHX mouthwashes were transferred to similar opaque bottles and were sequentially numbered.

Figure 5.

Mouthwashes dispensed in opaque bottles and sequentially numbered

Individuals were instructed to use 10 ml of mouthwash twice daily and 30 min after brushing and were instructed not to drink or eat anything for 30 min after using the prescribed mouthwashes.

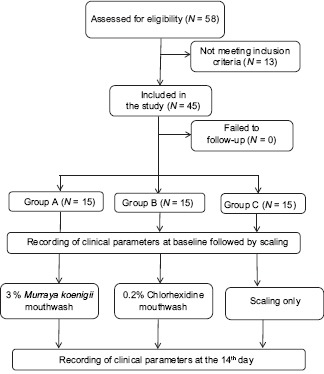

The participant data were recorded in a case history pro forma. The clinical parameters assessed were PI, GI, and oral hygiene index-simplified (OHI-S).[10] They were recorded at baseline and at the 14th day after using the prescribed mouthwashes [Flowchart 1]. The clinical parameters were recorded by the examiner who was blinded toward the allocation of participants.

Flowchart 1.

The above study design is represented in flow chart (N= Number of patients)

The primary outcome variable was the difference in mean reduction of GI scores from baseline to the 14th day. The secondary outcome variables were the differences in mean reduction of PI and OHI-S scores from baseline to the 14th day.

The following methods of statistical analysis were used in this study. The data collected were entered in Microsoft Excel, and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 10.5 software (Mission Hills, California, United States). One-way analysis of variance was used to test the difference between groups. For pairwise comparison between groups, post hoc test of Tukey was used. A paired t-test was performed to determine the difference between pre- and posttreatment measurements. In the above-used tests, P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the total 58 individuals who were assessed for the eligibility, 45 patients met the inclusion criteria and were randomly divided into three different groups. Demographic and clinical parameters were recorded. The mean age for Group A, Group B, and Group C were 31.2, 30.5, and 26.6, respectively.

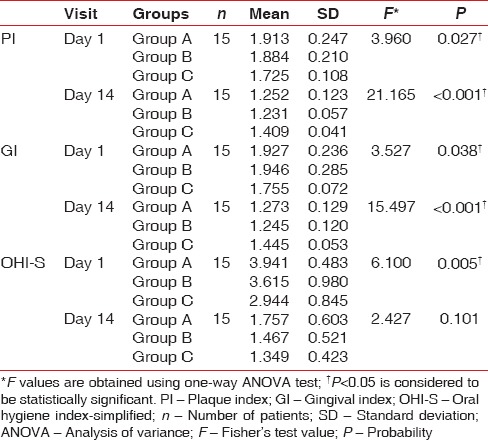

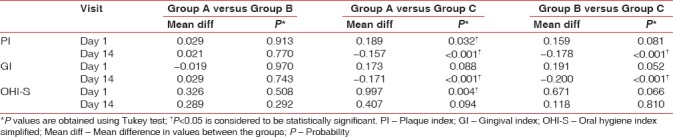

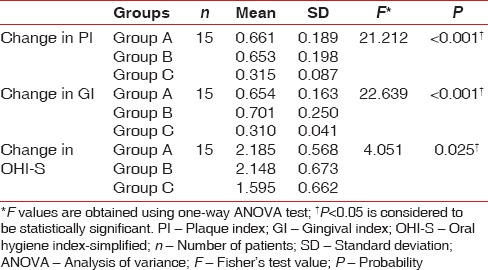

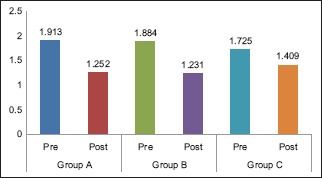

The mean PI scores for Group A, Group B, and Group C at baseline were 1.913, 1.884, and 1.725, respectively, and the mean difference in scores between the groups was statistically significant (P = 0.027). The PI scores on the 14th day were 1.252, 1.231 and 1.409 respectively. The mean difference in scores between the groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. On pairwise comparison of mean PI scores at baseline between the groups, Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P = 0.032). On comparing Group A versus Group B and Group B versus Group C, no statistically significant difference was noted (P > 0.05). On pairwise comparison between groups on the 14th day, Group B versus Group C and Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) while Group A versus Group B showed no significant difference [Table 2].

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical parameters between groups at different visits

Table 2.

Pairwise comparison of clinical parameters between the groups at different visits

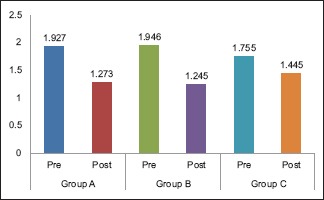

The mean GI scores for Group A, Group B, and Group C at baseline were 1.927, 1.946, and 1.755, respectively. The mean difference in scores between the groups was statistically significant (P = 0.038). The mean GI scores on the 14th day were 1.273, 1.245, and 1.445, respectively. The mean difference in scores between the groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. On pairwise comparison of GI scores at baseline between the groups, Group B versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P = 0.052). On comparing Group A versus Group B and Group A versus Group C, no statistically significant difference was noted (P > 0.05). On pairwise comparison between groups on the 14th day, Group B versus Group C and Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) while Group A versus Group B showed no significant difference [Table 2].

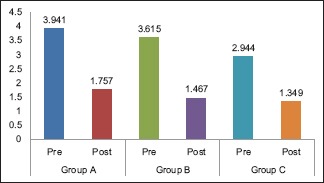

The mean OHI-S scores for Group A, Group B, and Group C at baseline were 3.941, 3.615, and 2.944, respectively. The mean difference in scores between the groups was statistically significant (P = 0.005). The mean OHI-S scores on the 14th day were 1.757, 1.467, and 1.349, respectively. The mean difference in scores between the groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.101) [Table 1]. On pairwise comparison of mean OHI-S scores at baseline between the groups, Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P = 0.004). On comparing Group A versus Group B and Group B versus Group C, no statistically significant difference was noted (P > 0.05). On pairwise comparison between groups on the 14th day, none of the groups showed a statistically significant difference [Table 2].

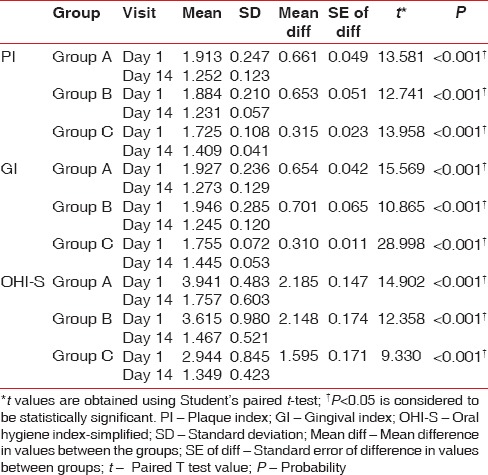

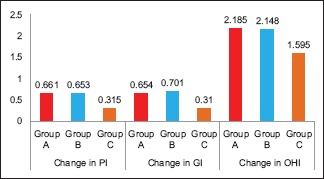

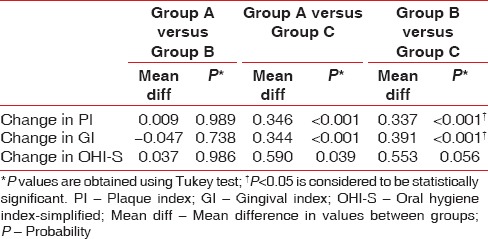

On intra- and inter-group comparison of difference in all clinical parameters at baseline and on the 14th day, all the three groups showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) [Tables 3, 4 and Graphs 1–4]. On pairwise comparison of changes in PI and GI scores between the groups, Group B versus Group C and Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) while Group A versus Group B showed no significant difference. On comparing OHI-S scores, Group A versus Group C showed a statistically significant difference [Table 5].

Table 3.

Intragroup comparison of clinical parameters

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of changes in clinical parameters

Graph 1.

Intragroup comparison of mean plaque index scores

Graph 4.

Intergroup comparison of changes in clinical parameters. PI – Plaque index; GI – Gingival index; OHI-S – Oral hygiene index-simplified

Table 5.

Pairwise comparison of changes in clinical parameters between the groups

Graph 2.

Intragroup comparison of mean gingival index scores

Graph 3.

Intragroup comparison of mean oral hygiene index-simplified scores

DISCUSSION

Ayurveda (Ayu – life and Veda – science) is a system of Indian medicine, which has been used effectively for the treatment of various systemic pathologic conditions. Ayurveda emphasizes the use of plant-based medicines, which are not only used for the treatment of systemic disease conditions but also their natural phytochemicals act as an effective substitute to traditional treatment modalities.[11]

Herbal products are currently replacing chemicals for the treatment of various diseases including periodontal diseases, because of their additional effectiveness and minimal reported side effects. Oral rinses made from herbal products are currently being used to treat gingival inflammatory conditions. M. koenigii is a green leafy vegetable grown all over India and other countries, used daily as an ingredient in Indian cuisine. The fresh curry leaves contain 2.6% volatile essential oils such as sesquiterpenes and monoterpenes which are soluble in water and have broad antimicrobial effects on Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis.[11] N-alkylated 3,6-dihalogenocarbazoles, a series of substituted carbazoles present in M. koenigii, exhibits fungicidal activity against Candida albicans.[12] The major component responsible for aroma and flavor has been given as pinene, sabinene, caryophyllene, cadinol, and cadinene. Curry leaves are known for their antimicrobial, antiemetic, antidiabetic, antiulcer, antioxidative, cytotoxic, and phagocytic activity. It also has anticancer and hepatoprotective properties.[13]

The commercially available CHX is considered as one of the most effective antiplaque agents in dentistry. However, its use for a long period is not recommended because of reported adverse effects. They are discoloration of teeth and alteration of taste, which can directly affect the patient's compliance. Herbal products can easily replace them to overcome these effects. Hence, the current trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of M. koenigii mouthwash in reduction of plaque and gingivitis and to compare with CHX.

Sunitha et al.[14] assessed MIC of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of M. koenigii against S. mutans. The mean diameter of inhibition zone was 16 and 13.05 mm, respectively. Bhuva et al.[15] reported the excellent inhibitory activity of M. koenigii extracts against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chandrashekar et al.[16] determined MIC of combination of Vachellia nilotica, M. koenigii, Eucalyptus hybrid, and Psidium guajava extracts on S. mutans, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and P. gingivalis. The formulation inhibited all microorganisms at low concentrations.

In the current study, the mean reduction in GI, PI, and OHI-S scores on the 14th day was statistically significant in all three groups. The reduction in GI and PI scores was significant on comparing Group A versus Group C and Group B versus Group C. The difference was not significant on comparing Group A and Group B. This denotes comparable efficacy of M. koenigii with CHX in inhibiting gingival inflammation.

The smaller sample size and the lack of microbiological confirmation of the findings can be considered as study limitations. Further long-term trials with large sample size are necessary to validate our results.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, M. koenigii mouthwash was found to be equally effective in reducing plaque and gingivitis. This finding throws light on the fact that herbal products are easily available, cost-effective, socially acceptable and reports minimal side effects compared to commercially available chemical products. Hence, it opens a new herbal era for the maintenance of periodontal health.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietrich T, Kaye EK, Nunn ME, Van Dyke T, Garcia RI. Gingivitis susceptibility and its relation to periodontitis in men. J Dent Res. 2006;85:1134–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keijser JA, Verkade H, Timmerman MF, Van der Weijden FA. Comparison of 2 commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CG. Chlorhexidine: Is it still the gold standard? Periodontol 2000. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradeep AR, Suke DK, Martande SS, Singh SP, Nagpal K, Naik SB, et al. Triphala, a new herbal mouthwash for the treatment of gingivitis: A Randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2016;87:1352–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.130406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solís C, Santos A, Nart J, Violant D. 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash with an antidiscoloration system versus 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash: A prospective clinical comparative study. J Periodontol. 2011;82:80–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sravani K, Suchetha A, Mundinamane DB, Bhat D, Chandran N, Rajeswari HR. Plant products in dental and periodontal disease: An overview. Int J Med Dent Sci. 2015;4:913–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Math MV, Balasubramaniam P. Curry leaves (Murraya koenigii Spreng) and halitosis. Br Med J. 2003;19:211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nithya RJ, Gala VC, Chaaya SS. Inhibitory effects of plant extracts on multi-species dental biofilm formation-in vitro. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2013;4:487–95. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sillness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease index. Ann Periodontol. 1964;4:655–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandita V, Patthi B, Singla A, Singh S, Malhi R, Vashishtha V. Dentistry meets nature-role of herbs in periodontal care: A systematic review. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2014;12:148–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tachibana Y, Kikuzaki H, Lajis NH, Nakatani N. Antioxidative activity of carbazoles from Murraya koenigii leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5589–94. doi: 10.1021/jf010621r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syam S, Abdul AB, Sukari MA, Mohan S, Abdelwahab SI, Wah TS, et al. The growth suppressing effects of girinimbine on HepG2 involve induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Molecules. 2011;16:7155–70. doi: 10.3390/molecules16087155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunitha JD, Patel S, Madhusudan AS, Ravindra SV. An in vitro antimicrobial activity of few plants extracts on dental caries microorganisms. Int J Appl Pharm Sci BMS. 2012;3:294–303. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhuva RM, Dixit YM. Comparative antimicrobial activities of neem and curry leaf extracts and their synergistic effect against selected pathogenic bacteria and fungus. Int Res J Pharm. 2015;6:755–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandrashekar BR, Nagarajappa R, Jain R, Suma S, Singh R, Thakur R. Minimum inhibitory concentration of the plant extracts' combinations against dental caries and plaque microorganisms: An in vitro study. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2016;14:456–62. [Google Scholar]