Abstract

Neurodevelopment is a transcriptionally orchestrated process. Cyclin K, a regulator of transcription encoded by CCNK, is thought to play a critical role in the RNA polymerase II-mediated activities. However, dysfunction of CCNK has not been linked to genetic disorders. In this study, we identified three unrelated individuals harboring de novo heterozygous copy number loss of CCNK in an overlapping 14q32.3 region and one individual harboring a de novo nonsynonymous variant c.331A>G (p.Lys111Glu) in CCNK. These four individuals, though from different ethnic backgrounds, shared a common phenotype of developmental delay and intellectual disability (DD/ID), language defects, and distinctive facial dysmorphism including high hairline, hypertelorism, thin eyebrows, dysmorphic ears, broad nasal bridge and tip, and narrow jaw. Functional assay in zebrafish larvae showed that Ccnk knockdown resulted in defective brain development, small eyes, and curly spinal cord. These defects were partially rescued by wild-type mRNA coding CCNK but not the mRNA with the identified likely pathogenic variant c.331A>G, supporting a causal role of CCNK variants in neurodevelopmental disorders. Taken together, we reported a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder with DD/ID and facial characteristics caused by CCNK variations, possibly through a mechanism of haploinsufficiency.

Keywords: developmental delay/intellectual disability, CCNK, de novo mutations, facial dysmorphism, zebrafish model

Main Text

Neurodevelopment is a complex and fine-tuned process, requiring well-orchestrated gene transcription and coordinated cellular activities from neurogenesis to formation of functional network.1 Disturbing this process can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders in human. Developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID) affects 1% of the population worldwide,2 and genetic causes were identified in up to 42% of the affected individuals.3, 4 Recent advance in genomic technologies greatly accelerates the discovery of genetic causes underlying these disorders, shedding light on the exquisite regulatory mechanisms of development.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), together with their corresponding cyclin partners, play major roles in the regulation of cell cycle and transcription.5 Human Cyclin K (CCNK), a protein with 580 amino acids, belongs to the subcategory of cyclins that do not oscillate with cell cycle and mainly participate in the transcriptional control.5 Together with its binding partner CDK12 or CDK13, CCNK regulates the RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription, especially the elongation of gene transcripts.6, 7 However, the physiological role of CCNK in human remains elusive, though the functional importance of CCNK can be perceived as the homozygous inactivation of CCNK caused embryonic lethality in mice.7 So far, the association between CCNK (MIM: 603544) and a human disorder has not been established.

Here we report four unrelated individuals harboring potentially pathogenic CCNK changes with de novo inheritance. These individuals were referred due to DD/ID and went through routine diagnostic testing of chromosomal microarray and whole-exome sequencing. Three of them harbor a deletion involving CCNK, and another one carries a rare nonsynonymous CCNK variant, all with de novo inheritance. Clinical information was collected through medical records or filled in by the referring physicians, and written consent was obtained from the parents of subjects in accordance with the approved protocol (XHEC-C-2017-067 by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital).

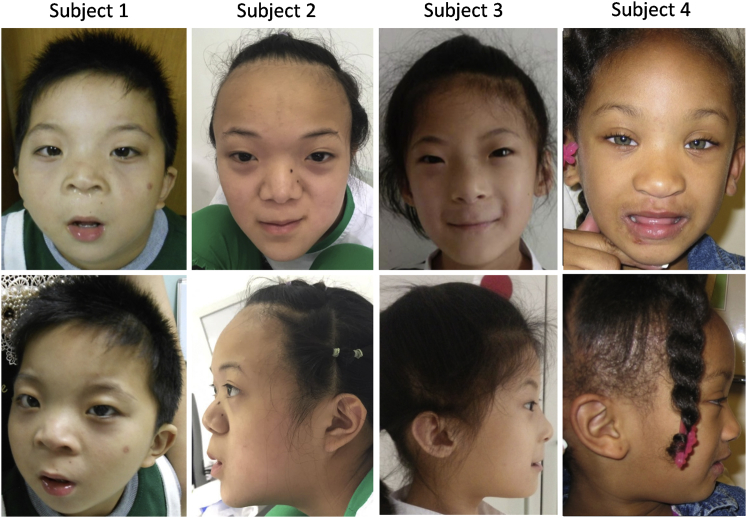

The key clinical phenotypes and variant information of these four individuals were summarized in Table 1. Subjects 1, 2, and 3 are Chinese from unrelated families. All of them exhibited severe to extremely severe DD/ID with profound defects in language. Subject 1 was diagnosed with severe ID. He was unable to speak at 4 years old, with language ability equivalent to 6 months (profound delay in speech and expression and severe delay in auditory perception and comprehension). Subject 2 exhibited extremely severe ID. She was not able to make sentences at the age of 9, with language ability equivalent to 18 months. The major developmental milestones, based on her parents’ report, were delayed, and her current cognitive and social skills at the age of 9 fell behind her 2-year-old sibling, who does not harbor the deletion involving CCNK. Subject 3 also exhibited severe ID and extremely severe delay of language development, with language ability equivalent to 13 months at the age of 6 years old. She also presented a stereotypic behavior of hand flapping. Subject 4 is an African American girl with moderate ID. Her gross motor and fine motor skills were mildly affected, and the language development was moderately delayed. Common facial dysmorphism observed in these four individuals included high hairline, hypertelorism, thin eyebrows, low-set ears with increased posterior angulation and dysmorphic antihelix or scapha, broad nasal bridge and tip, thin upper vermilion, and narrow jaw (Figure 1 and Table 1). Subjects 2 and 4 showed overgrowth (height and weight above 97 percentile) and macrocephaly. All of them reported no family history, and the birth history was unremarkable.

Table 1.

Clinical and Genetic Findings in Four Subjects Harboring De Novo CCNK Variants

| Subject 1 | Subject 2 | Subject 3 | Subject 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (hg19) | chr14:99670004–99987146 | chr14:99268957–100028788 | chr14:98058263–100498578 | chr14:99961886 |

| Type/size/inheritance | loss/317 kb/de novo | loss/760 kb/de novo | loss/2,440 kb/de novo | missense/SNV/de novo |

| Genes involved | BCL11B, SETD3, CCNK, CCDC85C | BCL11B, SETD3, CCNK, CCDC85C | C14orf177, BCL11B, SETD3, CCNK, CCDC85C, HHIPL1, CYP46A1, EML1 | CCNK |

| Gender, age at exam | male, 4 y | female, 9 y | female, 6 y | female, 13 y |

| Height | normal | >97% | normal | >97% |

| Weight | 90%–97% | >97% | normal | >97% |

| DD/ID | severe ID | extremely severe ID | severe ID | moderate ID |

| Gross motor skills | moderate | extremely severe | severe | mild |

| Fine motor skills | severe | extremely severe | severe | mild |

| Language | extremely severe | extremely severe | extremely severe | moderate |

| Social communication | extremely severe | extremely severe | extremely severe | − |

| Adaptivity | severe | extremely severe | severe | − |

| Autistic behaviors | + | − | + | − |

| Brain MRI | − | − | − | not available |

| Facial Dysmorphism | ||||

| Head circumference | +1 SD ∼+2 SD | +2 SD ∼+3 SD | −1 SD ∼−2 SD | +2 SD ∼+3 SD |

| Hypertelorism | + | + | + | + |

| Thin eyebrows | + | + | + | + |

| Dysmorphic ears | + | + | + | + |

| High anterior hairline | + | + | − | + |

| Palpebral fissure | + | + | + | + |

| Broad nasal bridge/tip | + | + | + | + |

| Thick nasal ala | + | + | + | + |

| Long philtrum | + | + | + | − |

| Thin upper vermilion | + | + | + | + |

| Narrow jaw | + | + | + | + |

| Other anomalies | none | none | None | tapered fingers, bilateral 5th finger clinodactyly, flat feet |

Figure 1.

Facial Dysmorphism of Four Subjects

Front and side views of subject 1 (at age 4 years), subject 2 (at age 9 years), subject 3 (at age 8 years), and subject 4 (at age 4 years). Common facial dysmporphism includes high hairline, hypertelorism, thin eyebrows, abnormal ears, broad nasal bridge and tip, thin upper vermilion, and narrow jaw.

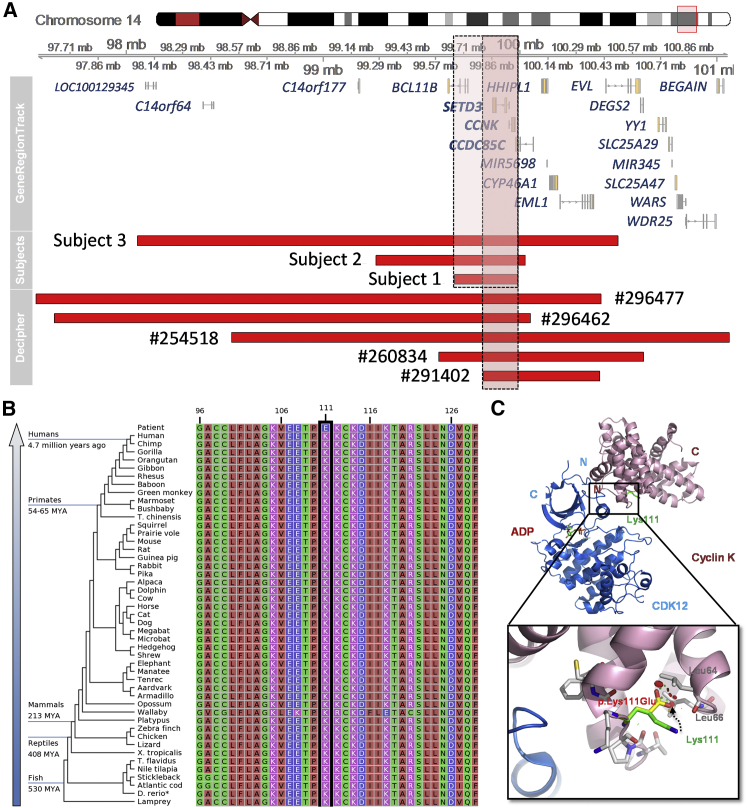

Subjects 1, 2, and 3 harbor heterozygous copy number losses in 14q32.2 region (Figure 2A and Table 1). Across the genome, no other rare CNVs with potential clinical significance were found in these three individuals (full list of CNVs detected was in Table S1). All three deletions were de novo, with paternity confirmed. Whole-exome sequencing was also performed, and no suspected pathogenic variant was identified (methods described in Table S2). The minimal overlapping region of these three deletions was restricted to chr14:99670004–99987146 (hg19), a 317 kb region with four genes included: BCL11B (MIM: 606558), SETD3 (MIM: 615671), CCNK, and CCDC85C (Figure 2A). Among these four genes, only one entry of CCDC85C (a missense variant in an individual affected with autism) was archived in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD),8 leaving the clinical relevance of these genes largely uncertain.

Figure 2.

De Novo CCNK Variants Identified in Four Subjects

(A) Chromosomal positions and gene contents of deletions identified in subject 1, 2, and 3 and Decipher cases (#291402, #260834, #296462, #254518, #296477) with the minimal overlapping regions highlighted.

(B) Conservation of amino acid sequence flanking the p.Lys111Glu variant detected in subject 4.

(C) Protein structural modeling of CDK12/CCNK and p.Lys111Glu variant by pyMol (using a 2.2 Å resolution crystal structure, PDB: 4un0).

By querying the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), BCL11B and CCDC85C were found to be present in multiple CNVs with >1% frequency (DGV: esv23236, esv832872, esv2658925; esv12661, esv23792), thus unlikely to be the primary responsible genes. CNVs intersecting the other two genes—CCNK and SETD3—were rare in DGV, and the frequency was far below 1‰ in the general population. We further queried the probability of loss-of-function (LoF) intolerance in ExAC database9 and found CCNK with a pLI score of 1.0, indicating extreme intolerance of LoF variants, while SETD3 has a score of 0.34, indicating tolerance of LoF variants in a moderate degree. Taken together, CCNK is the prioritized candidate among these four genes in the minimal overlapping region.

We subsequently searched the Decipher database for overlapping deletions within our candidate region. A total of five deletions below 3 Mb were found, with CCNK, SETD3, and CCDC85C shared by these deletions and our subjects (Figure 2A). DD/ID is the common phenotype that is present in all five case subjects (Table S3). Additional features overlapping with our subjects include hypertelorism, abnormality of the ear, and abnormal facial shape (Table S3). The phenotypic differences among these five case subjects and our subjects could be explained by involvement of different set of genes other than CCNK, SETD3, and CCDC85C. Notably, microcephaly was observed in the subjects with relatively larger deletions, including our subject 3, Decipher #296462 and #296477, which could be attributed by the effects of gene deletions outside the minimal overlapping region.

A de novo missense variant of CCNK (GenBank: NM_001099402.1; c.331A>G [p.Lys111Glu]) identified in the fourth individual with similar phenotypic presentations added evidence to support CCNK as the primary candidate. Though the individual is from different ethnic background, the phenotypic features of DD/ID with language delay and facial dysmorphism resemble the clinical findings in subjects 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 1, Table 1). No other variant of clinical significance was found in this individual by whole-exome sequencing (see Table S2 for details) and chromosomal microarray. This c.331A>G variant was not observed in any population database including ExAC9 and gnomAD.9 It locates at the functional domain of cyclin box, within a highly conserved region in the aspects of amino acid sequence (Figure 2B) and complex configuration (Figures S1A and S1B). The putative impact can be depicted with in silico atomic structure analyses by pyMol. This substitution was mapped in the heterodimeric interface of CDK12/CCNK complex (Figure 2C), and mapping in the CDK13/CCNK complex was similar (Figures S1C and S1D). The adjacent residue around Lys111 has close contacts with CDK12 or CDK13. Replacement of lysine with glutamine changed the hydrophilic positively charged nitrogen atom with negatively charged oxygen atom. It was also located on the solvent-exposed surface. This change would likely cause steric hindrance with leucine at 64 and 66 of CCNK protein, leading to instability of the complex.

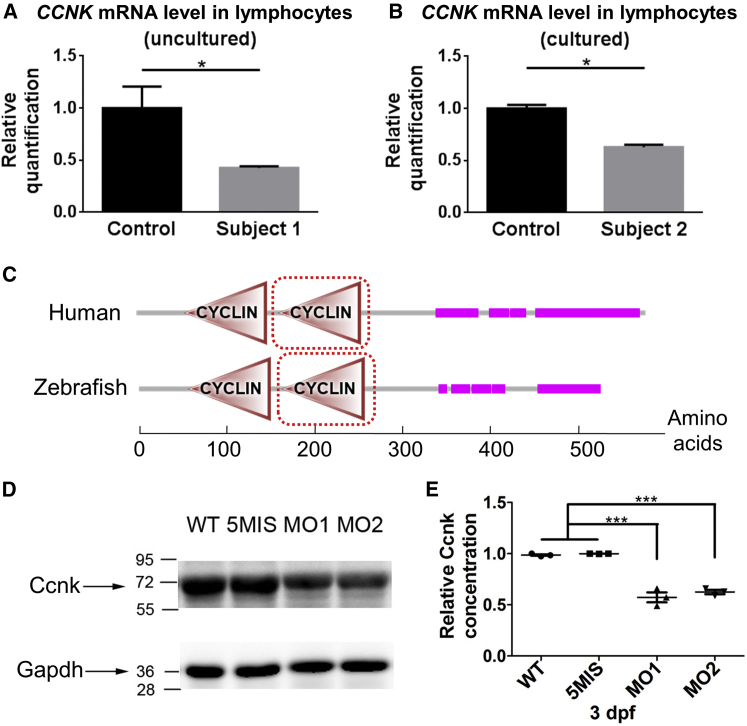

To confirm the de novo genomic deletions indeed alter CCNK expression, we performed quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed mRNA extracted from the lymphocytes of subjects 1 and 2 (while no tissue was available for assessment of subjects 3 and 4). The relative level of CCNK mRNA was significantly reduced when compared to age-matched healthy control subjects (Figures 3A and 3B; approximately 57% reduction in subject 1 and 37% reduction in subject 2, compared to respective control subjects), consistent with the dosage effect of genomic copy number losses.

Figure 3.

CCNK mRNA Level in Lymphocytes of Affected Subjects and the Morpholino Knockdown Approach of Zebrafish Ccnk

(A and B) The relative quantification of CCNK RNA level based on quantitative PCR of reverse-transcribed mRNA (using PrimeScript RT reagent Kit from Takara and SYBR green master PCR mix from Applied Biosystems; primers were described in Table S6). As the available subject samples were in different forms, control samples from age-matched individuals were prepared accordingly. The mRNA sample of subject 1 was extracted from uncultured lymphocytes (n = 3, control n = 12); mRNA of subject 2 was extracted from cultured lymphocytes (n = 3). Error bars: SEM, ∗p < 0.001, t test.

(C) The predicted human CCNK and zebrafish Ccnk protein structure. Pink horizontal bars: the low-complexity motifs (proline-rich domains); triangles: cyclin box; dashed lines: cyclin_C domains (the regulatory region to activate the CDK).

(D and E) The knockdown specificity and efficiency of the ccnk MO1 and MO2 were analyzed by western blot. The band density was quantified with ImageJ software and Gapdh protein was used for normalization. The relative level of wild-type (WT) was normalized to 1. Embryos that received injections of the ccnk MO1 or MO2 (4 ng per embryo) showed reduction of Ccnk expression (WT: 0.986 ± 0.007; MO1: 0.574 ± 0.049, at ∗∗∗p < 0.001; MO2: 0.626 ± 0.021, at ∗∗∗p < 0.001; 5MIS: 0.999 ± 0.001; n = 3 batches, with 30 embryos per batch). Antibodies used: rabbit anti-CCNK, 1:1,000, ab130475, Abcam; mouse anti- GAPDH, 1:1,000, Proteintech.

To further interrogate the causality of CCNK variations, we employed the zebrafish larvae to study Ccnk knockdown effects on neurodevelopment. We examined the mRNA expression pattern of ccnk at different developmental stages with whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH). The zebrafish ccnk transcripts were widely detected at 1 day post-fertilization (dpf) and continuously expressed in the brain through development (Figure S2). The predicted zebrafish Ccnk protein has two cyclin domains and one cyclin_C domain—a structure highly conserved between zebrafish and human CCNK ortholog (Figure 3C). Zebrafish of the wild-type strain (WT) were reared under standard laboratory conditions10 (in accordance with protocol approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the USTC, Permit Number: USTCACUC1103013). We designed two morpholino oligonucleotides (MO1 against the ATG start codon and MO2 against the 5′ untranslated region, with sequences in Table S4) to knock down zebrafish Ccnk. For most of the following experiments, 4 ng dosage was used, for it produced a knockdown effect approximate to the heterozygotes: ∼40% reduction of protein level after the injection of ccnk MO1 or MO2 at 3 dpf based on western blots, while injection of the control morpholino (5-base-mismatch, 5MIS) did not alter the protein level (Figures 3D and 3E).

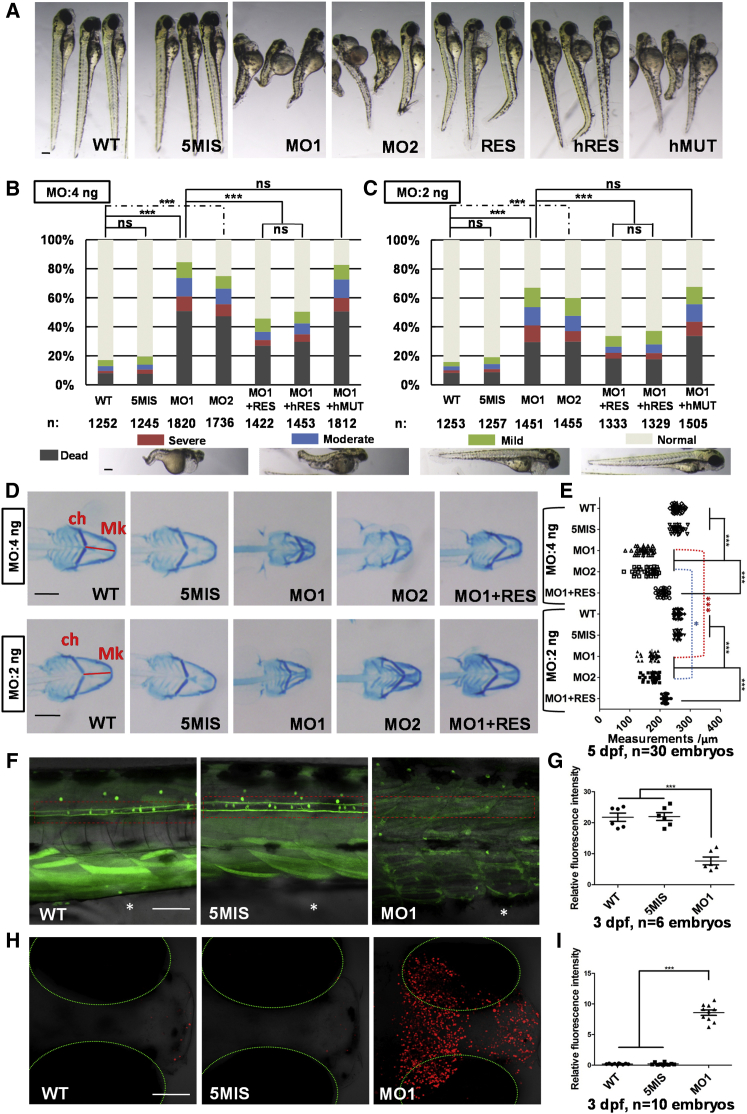

Knockdown of Ccnk by MO1 and MO2 resulted in unconsumed yolk sac, small eyes, deformed head, and curly spinal cord in zebrafish (Figure 4A). It is noteworthy that the injection of MO1 and MO2 resulted in dosage-dependent mortality at 3 dpf (∼30% at 2 ng, ∼50% at 4 ng, and more than 80% at 8 ng), while the group with injection of control morpholino 5MIS had low mortality rate at the same dose (below 10%) with no difference from the wild-type (Figure S3). To further test the knockdown specificity, rescue experiments were performed by re-introducing Ccnk back into the embryos with zebrafish ccnk or human CCNK mRNA (sequences of constructs were included in Table S5). When zebrafish ccnk or human CCNK mRNA was co-injected with MO1, the morphant phenotypes were at least partially rescued, but were not rescued by human CCNK mRNA with the c.331A>G variant (Figure 4B). At a lower dosage (2 ng MO injection), similar morphant phenotypes were observed, though overall milder (Figure 4C). We also observed a significant reduction of the distance between the ceratohyal and Meckel’s cartilage in MO1 and MO2 groups, indicating a reduced lower-jaw size, a dysmorphic feature similar to the human subjects harboring CCNK variants (Figures 4D and 4E). This reduction was dose dependent as the alteration of cartilage patterning in 2 ng MO1 group was milder than 4 ng group (Figures 4D and 4E). The CRISPR/Cas9-based ccnk genome knockout experiments were also performed in zebrafish, and similar morphant phenotypes were observed in ccnk knockout-F0 embryos at 3 dpf as in the morpholino-based knockdown experiments (Figure S5), further confirming the specificity of our ccnk morpholino approach. Taken together, ccnk morpholino resulted in dose-dependent and consistent alteration of zebrafish morphogenesis and cartilage patterning, and overall the anomalies were more severe than presentations in human.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of Ccnk Caused Developmental Defects in Zebrafish

(A) The gross morphology of the 3 dpf morphants. The morphology of the uninjected (WT) and control MO-injected embryos (5MIS group, 4 ng per embryo) appeared largely normal, whereas the embryos injected with ccnk MO1 or ccnk MO2 showed growth defects, including unconsumed yolk sac, small eyes, deformed head, and curly spinal cord. The abnormal phenotypes were partially rescued by co-injections of zebrafish ccnk mRNA (RES) or human CCNK mRNA (hRES) (200 pg per embryo) but were not rescued by human CCNK mutant mRNA with c.331A>G (hMUT).

(B and C) The phenotypic classification of morphants, with 4 ng (B) and 2 ng (C) dosage of MO injection. The 3-dpf injected embryos were classified by morphological criteria into five categories (normal, mild, moderate, severe, and dead, as indicated below the chart), and their proportions were shown in the stacked-bar graphs (the number of embryos used was labeled under each group name, pooled from three different batches). ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05, Chi-square test.

(D) Ventral views of 5 dpf whole-mount Alcian-blue staining embryos at two different MO doses, 4 ng and 2 ng. The cartilage staining method was as previously described.11 The cartilage structures were visualized and the distance between ceratohyal cartilage (ch) and Meckel’s cartilage (Mk) were measured by ImageJ software (red lines).

(E) The distance between ch and Mk cartilages with 4 ng and 2 ng MO injection. While the mean distance in wild-type was 258 μm (SEM: 1.8 μm), the MO1 4 ng group was significantly shorter, 146 μm (SEM: 4.4 μm). If compared with the 2 ng MO1 group (mean distance 173 μm, SEM: 4.2 μm), the 4 ng MO1 group was approximately 27 μm shorter with statistical difference (n = 30 embryos for each group, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗p < 0.05, ns: p > 0.05, t test).

(F and G) Knockdown of Ccnk affects primary motor neuronal development. The primary motor neuronal large-caliber Mauthner axons were analyzed in Tg(tol-056:GFP) zebrafish line. The branches of the Mauthner axons disappeared after Ccnk knockdown (n = 6 embryos, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, t test). The dashed line labels spinal cord, and the anal pore site was marked by an asterisk (*).

(H and I) Knockdown of Ccnk induced neural cell death. The intense fluorescent apoptotic foci in the head were detected by TUNEL assay of 3 dpf embryos (n = 10 embryos per group, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Dashed lines: eye region.

Scale bar: 200 μm (A, B, and D), 50 μm (F and H).

The phenotypes observed in zebrafish larvae, such as small eyes, deformed head, and curly spinal cord, suggest a role of Ccnk in the development of central nervous system (CNS). When analyzing the primary motor neuronal Mauthner axons with live imaging of the Tg(tol-056:GFP) transgenic line,12 the branches of Mauthner axons in the MO1 group disappeared compared with those in the WT group and 5MIS group (Figures 4F and 4G), implying a CNS defect possibly mediated by neural cell death. We further employed TUNEL assay to investigate the apoptosis in 3 dpf embryos (Figure 4H, TUNEL BrightRed Kit from Vazyme). Intense fluorescent apoptotic foci in the head were detected in MO1 group, suggesting prominent cell death in CNS was induced by Ccnk knockdown (Figures 4H and 4I).

Our genetic and experimental investigations suggest a syndrome likely caused by CCNK variants. The phenotypic features include DD and moderate-to-severe ID with special defects in language, and a distinctive facial appearance of hypertelorism, thin eyebrows, dysmorphic ears, broad nasal bridge and tip, and narrow jaw. A recent study reported that de novo missense variants of CDK13, encoding the binding partner of CCNK, caused a syndromic form of ID, with craniofacial anomalies like hypertelorism, posteriorly rotated ears, and thin upper lip vermilion that partially overlap with our subjects.13 Of note, a common digital anomaly observed in the carriers of CDK13 mutations—the fifth finger clinodactyly—was found in our subject 4 with the CCNK missense variant c.331A>G. Some of the reported mutations of CDK13 were predicted to affect CCNK binding or reduce the ability of transmitting CCNK activation.13 These findings suggest the importance of CDK13/CCNK complex in human development.

We propose haploinsufficiency as the primary mechanism, based on the fact that subjects 1, 2, and 3 harbor copy number loss of CCNK. Subject 4, carrying a heterozygous missense variant in the conserved domain, showed relatively milder ID. Based on structural modeling, p.Lys111Glu causes instability of the protein, likely leading to partial loss of function. In our zebrafish experiments, injection of the human CCNK mRNA alone (either wild-type or the hMUT c.331A>G variant) did not alter the morphogenesis of zebrafish larvae (Figure S4), while the same dosage of mRNA partially rescued the morphant phenotypes resulted by morpholino knockdown (Figures 4B and 4C), also supporting haploinsufficiency instead of dominant toxicity as the main mechanism. In transgenic mice, the homozygous inactivation of Ccnk was embryonically lethal, whereas the heterozygotes “appeared” normal and reproduced well.7 This might contradict a haploinsufficiency model. However, the cognitive and social defects, as well as craniofacial anomalies, could be mild or overlooked in mice, which warrants further evaluation. In addition, disrupting the same gene can result in phenotypes with different severity across species, which has been reported before.14

Potential biological connections of CCNK with human intellectual development can be found in literature. CCNK variations may affect RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription and disturb early brain development. Previous studies have shown that CCNK forms complex with CDK12/CDK13 and regulates the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II.6, 7 This phosphorylation is responsible for productive elongation of transcripts and synthesis of full-length mature mRNA.15 Previous studies on depletion of CCNK/CDK12 also showed altered expression of a subset of human genes mediated by RNA polymerase II, among which a prominent group—the DNA damage response (DDR) genes—were downregulated.7 Downregulation of DDR could result in genomic instability and cellular death. Consistent with this notion, DNA strand breaks were detected by TUNEL assay after depletion of Ccnk in our zebrafish model, implying defected mechanism of DDR and DNA repair. Except for the impact on DDR gene expression, RNA polymerase II is also involved in the fine-tuning of global gene expression pattern during neural precursor cell differentiation.16 CCNK variations may disturb the spatial and temporal control of RNA polymerase II and thus disturb the differentiation process. This postulation coincides with the expression pattern of CCNK—abundantly expressed at pluripotent embryonic stage and gradually decreased in differentiated tissues.17 How CCNK participates in the exquisite tuning of RNA polymerase II activity during early brain development is a direction of future investigation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates CCNK is a regulator of neurodevelopment. CCNK variations in human could result in DD/ID with distinctive facial dysmorphism. Future clinical, genetic, and functional studies are warranted to further delineate the phenotypic spectrum and etiology of CCNK-associated disorders.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Feng Zhang for constructive comments, Dr. S. Higashijima for the tol-056 transgenic fish line, Jiu-Lin Du for the zebrafish AB strain, Tin-Xi Liu for providing the gift of pCS2+ vector, and Xia Zhang, Zhiqing Hu, Yue Tao, Nan Shen, and Xi Mo for assisting the experiments during the revision. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81500972 to Y.F., no. 81670812 to Y.Y., no. 31571313 to D.L., no. 31571068 to B.H.), the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (no. 15CG14 to Y.F.), the Jiaotong University Cross Biomedical Engineering (no. YG2017MS72 to Y.Y.), the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (no. 201740192 to Y.Y.), the Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Center new frontier technology joint project (no. SHDC12017109 to Y.Y.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2015M571941 to W.Y.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (to W.Y.), and the National Key R&D Program of China (no. SQ2017YFSF080012 to L. Wu).

Published: August 16, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include five figures and six tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.019.

Contributor Information

Lingqian Wu, Email: wulingqian@sklmg.edu.cn.

Yongguo Yu, Email: yuyongguo@shsmu.edu.cn.

Accession Numbers

Variants were deposited to LOVD, Variant ID #392006, #392007, #392008, and #392009.

Web Resources

Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home

DECIPHER, https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

gnomAD Browser, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

RCSB Protein Data Bank, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Kandel E.R. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2013. Principles of Neural Science. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maulik P.K., Mascarenhas M.N., Mathers C.D., Dua T., Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011;32:419–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moeschler J.B., Shevell M., Committee on Genetics Comprehensive evaluation of the child with intellectual disability or global developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e903–e918. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilissen C., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Thung D.T., van de Vorst M., van Bon B.W., Willemsen M.H., Kwint M., Janssen I.M., Hoischen A., Schenck A. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim S., Kaldis P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development. 2013;140:3079–3093. doi: 10.1242/dev.091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greifenberg A.K., Hönig D., Pilarova K., Düster R., Bartholomeeusen K., Bösken C.A., Anand K., Blazek D., Geyer M. Structural and functional analysis of the Cdk13/Cyclin K complex. Cell Rep. 2016;14:320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blazek D., Kohoutek J., Bartholomeeusen K., Johansen E., Hulinkova P., Luo Z., Cimermancic P., Ule J., Peterlin B.M. The Cyclin K/Cdk12 complex maintains genomic stability via regulation of expression of DNA damage response genes. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2158–2172. doi: 10.1101/gad.16962311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunami N., Hensel C.H., Baird L., Stevens J., Otterud B., Leppert T., Varvil T., Hadley D., Glessner J.T., Pellegrino R. Identification of rare DNA sequence variants in high-risk autism families and their prevalence in a large case/control population. Mol. Autism. 2014;5:5. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerfield M. M. Westerfield; Eugene, OR: 1993. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beunders G., Voorhoeve E., Golzio C., Pardo L.M., Rosenfeld J.A., Talkowski M.E., Simonic I., Lionel A.C., Vergult S., Pyatt R.E. Exonic deletions in AUTS2 cause a syndromic form of intellectual disability and suggest a critical role for the C terminus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satou C., Kimura Y., Kohashi T., Horikawa K., Takeda H., Oda Y., Higashijima S. Functional role of a specialized class of spinal commissural inhibitory neurons during fast escapes in zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:6780–6793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0801-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton M.J., Caswell R.C., Canham N., Cole T., Firth H.V., Foulds N., Heimdal K., Hobson E., Houge G., Joss S. Heterozygous mutations affecting the protein kinase domain of CDK13 cause a syndromic form of developmental delay and intellectual disability. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:28–38. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen L.D., Nakamura M., Bräutigam L., Li X., Liu Y., Samani N.J., Cao Y. VEGF-B-Neuropilin-1 signaling is spatiotemporally indispensable for vascular and neuronal development in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E5944–E5953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510245112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterlin B.M., Price D.H. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J., Wu X., Zhang H., Pfeifer G.P., Lu Q. Dynamics of RNA polymerase II pausing and bivalent histone H3 methylation during neuronal differentiation in brain development. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1307–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Q., Lei T., Zhao C., Zhong J., Tang Y.Z., Chen B., Yang J., Li C., Wang S., Song X. Cyclin K-containing kinase complexes maintain self-renewal in murine embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:25344–25352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.