Abstract

Tetrahydrolipstatin (THL) is a covalent inhibitor of many serine esterases. In mycobacteria, THL has been found to covalently react with 261 lipid esterases upon treatment of Mycobacterium bovis cell lysate. However, the covalent adduct is considered unstable in some cases because of the hydrolysis of the enzyme-linked THL adduct resulting in catalytic turnover. In this study, a library of THL stereoderivatives was tested against three essential Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipid esterases of interest for drug development to assess how the stereochemistry of THL affects respective enzyme inhibition and allows for cross enzyme inhibition. The mycolyltransferase Antigen 85C (Ag85C) was found to be stereospecific with regard to THL; covalent inhibition occurs within minutes and was previously shown to be irreversible. Conversely, the Rv3802 phospholipase A/thioesterase was more accepting of a variety of THL configurations and uses these compounds as alternative substrates. The reaction of the THL stereoderivatives with the thioesterase domain of polyketide synthase 13 (Pks13-TE) also leads to hydrolytic turnover and is nonstereospecific but occurs on a slower, multihour time scale. Our findings suggest the stereochemistry of the β-lactone ring of THL is important for cross enzyme reactivity, while the two stereocenters of the peptidyl arm can affect enzyme specificity and the catalytic hydrolysis of the β-lactone ring. The observed kinetic data for all three target enzymes are supported by recently published X-ray crystal structures of Ag85C, Rv3802, and Pks13-TE. Insights from this study provide a molecular basis for the kinetic modulation of three essential M. tuberculosis lipid esterases by THL and can be applied to increase potency and enzyme residence times and enhance the specificity of the THL scaffold.

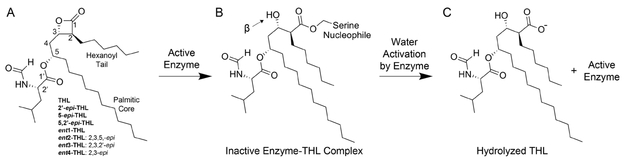

Tetrahydrolipstatin (THL) is a stable, synthetic derivative of the naturally occurring human pancreatic lipase inhibitor, lipstatin, produced by Streptomyces toxytricini. 1 Initially, THL was found to inhibit the pancreatic lipase, gastric lipases, and the carboxyl ester lipase (cholesterol esterase). Human lipase inhibition results in the reduction of fat absorption, leading THL (Orlistat) to be used as a Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment for obesity.2 Inhibition of the cholesterol esterase by THL is covalent, yet unstable in aqueous solutions.1 Covalent inhibition proceeds through an acyl-enzyme type inhibitor–enzyme complex as a result of nucleophilic attack on THL by the enzyme.1 Nucleophilic attack occurs on the carbonyl center of the β-lactone ring by the serine nucleophile, resulting in ring opening (Figure 1 A,B).1 However, this acyl–enzyme complex is subject to catalytic turnover because of water activation by the enzyme.1 Subsequent hydrolysis of the acyl–enzyme complex leads to the recovery of enzymatic activity and inactivation of the inhibitor (Figure 1 B,C).1 This inactivation of the β-lactone moiety is analogous to β-lactam inactivation by β-lactamases and carbapenemases.3,4

Figure 1.

THL structure and mode of inhibition. (A) THL has four stereocenters at carbons 2, 3, 5, and 2′, and the carbonyl at position 1 is subject to nucleophilic attack.1 Names of stereoderivatives tested with the corresponding change in the stereocenter. (B) Nucleophilic attack by the catalytic serine of serine esterases results in β-lactone ring opening and formation of an ester-linked enzyme–THL covalent complex.1 (C) Covalent intermediate formation of some esterases by THL is considered unstable because of hydrolysis of the acyl–enzyme complex as a result of water activation by the catalytic histidine.1,9

An additional in vivo target of THL was later found to be the thioesterase domain of the human fatty acid synthase (FAS).5Because of the overexpression of FAS in a variety of tumor cells, THL has been proven to be a potential cancer therapeutic.5-7 In 2007, the X-ray crystal structure of THL in complex with the thioesterase domain of FAS was determined having two protein molecules in the asymmetric unit.8 The THL acyl–enzyme covalent complex was observed in one protein molecule, while a bound, hydrolyzed form of THL was observed in the second protein molecule.8 In the intact THL acyl–enzyme protein molecule, the catalytic histidine is hydrogen bonded to the β-hydroxyl of THL that forms following β-lactone ring opening.8,9 However, when this interaction is disrupted, the catalytic histidine is free to activate a water molecule to promote nucleophilic attack on the THL acyl–enzyme ester linkage.9 The THL–FAS structure and subsequent computational modeling provided a molecular basis for the observed catalytic turnover of the inhibited covalent complex by THL.

The pleiotropic effects exhibited by THL are not exclusive to human lipases, and THL is known to target a myriad of lipid esterases (serine esterases) in mycobacteria.10 Mycobacterium bovis (Mbovis) cell lysate treated with biotin-labeled or fluorescently labeled THL derivatives resulted in the identification of 261 target proteins using mass spectrometry analysis of the enriched sample (biotin-THL pull-down), and 14 of the 261 target proteins were cross validated using the fluorescently labeled THL and non-enriched sample.10 However, this nonspecific targeting of lipid esterases results in an minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against Mtb strain H37Rv of ~15 μM.11 One reason for the modest THL MIC against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and non-tuberculosis mycobacteria may be the rapid degradation of THL by esterases capable of hydrolyzing the ester linkage of the THL–enzyme covalent complex. Given the high number of potential targets of THL in Mtb, the question of what attributes of THL make the molecule such a promiscuous inhibitor of lipid esterases in mycobacteria remains. One plausible rationale is that the two-alkyl chains of THL mimic the fatty acid chains of mycobacterial lipids, enhancing the affinity for the lipid-binding sites of lipid esterases.12 More so, there may be an aspect of substrate mimicry as the core scaffold of THL is structurally similar to that of mycolic acids, a major lipid essential for Mtb growth, viability, and pathogenesis.13 Clearly, the moderately reactive β-lactone moiety that mimics the ester linkage found in countless lipids is also important. Another important structural attribute of THL is the presence of four stereocenters within the molecule. These centers reside on carbons 2 and 3 of the β-lactone ring, carbon 5 on the palmitic core, and carbon 2′ on the peptidyl side chain (Figure 1A). In this study, a library of THL stereoderivatives was used to assess the influence of THL stereochemistry on the in vitro inhibition of three essential Mtb-encoded lipid esterases/transferases (derivative names given in Figure 1A and full derivative structures given in Figure S1).14,15

The three lipid esterases included in this study are Antigen 85C (Ag85C), Rv3802, and the thioesterase domain of polyketide synthase 13 (Pks13-TE). All three essential enzymes use a catalytic triad of serine, histidine, and glutamic or aspartic acid, have α/β-hydrolase folds, bind substrates possessing two aliphatic moieties, and have been successfully targeted for drug development.11,16–28 Ag85C is one of three essential, secreted mycolyltransferases responsible for the final transfer of mycolic acid, producing trehalose dimycolate or mycolylarabinogalactan; both products are major lipids of the outer Mtb mycomembrane.16,17 The Mbovis homologue of Ag85C was identified as one of the 14 validated targets of THL.10 Recently, our lab published the X-ray crystal structure of Mtb Ag85C in a covalent complex with THL.18 Covalent inhibition by THL stimulates a conformational change that results in the displacement of the catalytic histidine of Ag85C, yielding an irreversible, acyl–enzyme inhibited complex.18 The observed inhibitory mechanism and specific noncovalent interactions between Ag85C and THL are in stark contrast to those of human FAS and THL.8,18 The second lipid esterase tested was the Rv3802 enzyme encoded by the Mtb rv3802c gene. Rv3802 is localized to the periplasmic region of Mtb and possesses general thioesterase/esterase activity.19,20 Additionally, the enzyme has been shown to have phospholipase A activity toward phosphatidyl-based substrates.19,20 The enzyme is considered essential and has been associated with the modulation of lipid content within the mycomembrane.21,22 Previously, a series of THL derivatives were developed and tested against Rv3802 in vitro showing nanomolar IC50 values with correlated improvements of inhibition in vivo against Mtb.11 The Mbovis homologue of Rv3802 was identified as one of the 261 potential target proteins of THL but was not one of the 14 cross validated targets.10 The third lipid esterase tested was the thioesterase domain of Pks13. Pks13 is a large, multidomain enzyme, residing within the cytoplasm of Mtb, and is responsible for the condensation of the two-alkyl chains of mycolic acid, producing β-keto mycolic acid.23 The Pks13 thioesterase domain possesses a nucleophilic serine residue that becomes acylated with β-keto mycolic acids and subsequently catalyzes the transfer of mycolic acids to trehalose.24 The Mbovis homologue of Pks13 was not identified as one of the 261 targets of THL.10 The results from this study suggest that the unique stereochemistry of THL is required to inhibit numerous Mtb lipid esterases and that alteration of the stereochemistry at these positions directly influences the stability of the inhibitor–enzyme covalent complex. Ultimately, this study provides a basis for the further development of more potent and more specific THL scaffolds toward Ag85C, Rv3802, and Pks13.

■ EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Molecular Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification of Ag85C, Rv3802, and Pks13-TE.

Both Mtb Ag85C and Rv3802 were recombinantly expressed and purified as previously published.27,28 In short, Rv3802 was recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli using a pET32 plasmid that encodes a cleavable N-terminal polyhistidine-tagged protein. Rv3802 was overexpressed as insoluble inclusion bodies at 37 °C for 3 h; pelleted cells were resuspended and lysed in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 250 mM NaCl. Following centrifugation, the resulting pellet was washed with resuspension buffer and again centrifuged, and the washed inclusion bodies were then solubilized in 4 M GuHCl and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and centrifuged. The soluble protein was bound to an equilibrated 5 mL metal affinity column (Cobalt, GE Healthcare), and washed protein was then eluted using 10 column volumes (CV) of 4 M GuHCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and 150 mM imidazole. Protein was refolded into 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 250 mM NaCl using extensive dialysis at 4 °C. Refolded, soluble protein was subsequently dialyzed into 50 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.5) for enzyme inhibition assays.

Ag85C was recombinantly expressed in E. coli using a pET29 plasmid that encodes a noncleavable C-terminal polyhistidine-tagged protein. Protein was overexpressed at 16 °C for 24–36 h. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Following cell lysis and centrifugation, the clarified lysate was applied to an equilibrated 5 mL metal affinity (cobalt) column (GE Healthcare), unbound protein was removed with a column wash step, and the target protein was then eluted using 15 CV of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 150 mM imidazole. Eluted protein was then bound to an equilibrated 5 mL anion exchange column (GE Healthcare), washed, and eluted using a linear gradient over 15 CV to 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.3 mM TCEP, and 1 M NaCl. Eluted protein was subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation (2.8 M), pelleted, resuspended in 50 mM NaPO4 buffer (pH 7.5), and dialyzed against the same buffer to remove residual ammonium sulfate.

The predicted TE domain from Mtb Pks13 was cloned on the basis of the previously published truncated form.26 The gene encoding the desired TE domain was amplified from a pET32 plasmid containing the full-length Pks13 gene that was codon optimized for E. coli expression. Primers used to amplify the TE domain are 5′-GCT GTT CCA GGG ACC TCA AAT CGA TGG GTT TGT TCG G-3′ and 5′-TTC GGA TCC GGA CGC TCA CTG CTT CCC TAC CTC GCT CGT-3′. The primers used to amplify the desired gene contained 5′ and 3′ overhangs that afforded insertion into a pET32 plasmid linearized with PshA1 using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB) to make the desired plasmid. The resulting construct (pET32-Pks13-TE) encodes a cleavable N-terminal polyhistidine-tagged protein. Chemically competent T7 express E. coli cells (NEB) were transformed with the pET32-Pks13-TE plasmid. Cultures were grown at 37 °C in LB medium containing carbenicillin; upon reaching an OD600 of 0.6, cultures were cooled to 16 °C and induced through the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Induced cells were harvested following induction for 16 h.

Mtb Pks13-TE was purified in a manner similar to a previously published methodology.26 Pelleted cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-Me, and 10% glycerol (lysis buffer) and lysed by sonication after being incubated for 30 min on ice with addition of DNase and lysozyme. The cell lysate was clarified via centrifugation and loaded onto a 5 mL metal affinity (cobalt) column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with lysis buffer. Protein was eluted with a linear gradient from 0 to 150 mM imidazole in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-Me, and 10% glycerol. Eluted fractions containing Pks13-TE were pooled, and the histidine tag was removed using Precision Protease (GE Healthcare) via overnight dialysis against 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-Me, and 10% glycerol at 4 °C. The cleaved histidine tag and Precision Protease were removed by applying the protein solution to an equilibrated 5 mL metal affinity column and collecting Pks13-TE in the flow-through. The Pks13-TE was concentrated and loaded onto a HiLoad16/200 Superdex-200 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 10% glycerol. The single peak containing Pks13-TE was pooled and extensively dialyzed against a 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 overnight at 4 °C.

Ag85C Activity Assay.

Mtb Ag85C activity was assessed using a previously published fluorescence-based assay that monitors the transfer of butyrate from resorufin butyrate (RfB, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to trehalose.28 In brief, reaction mixtures consisted of 500 nM enzyme, 4 mM trehalose [500 mM stock in 50 mM NaPO4 buffer (pH 7.5)], 1% (v/v) DMSO, or the respective inhibitor and reactions initiated upon titration of 100 μM RfB (10 mM stock in DMSO). Kinetic data were acquired at 37 °C in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) using a λex of 500 nm and a λemit of 590 nm with relative fluorescence intensities acquired on a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek). All reactions were performed in triplicate with background hydrolysis of the substrate subtracted (identical reaction above, sans enzyme).

Rv3802 Activity Assay.

Mtb Rv3802 activity was measured using a previously published fluorescence-based assay that monitors the hydrolysis of the heptanoate from 4-methylumbelliferyl heptanoate (4MH, Sigma).27 In short, reaction mixtures consisted of 20 nM enzyme, 1% (v/v) DMSO, or the respective inhibitor and reactions initiated upon addition of 75 μM 4MH (7.5 mM stock in DMSO). Triplicate reactions were performed at 37 °C in 50 mM NaPO4 buffer (pH 7.5) using a λex of 360 nm and a λemit of 450 nm with relative fluorescence intensities acquired every 30 s on a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek). Background hydrolysis of 4MH was subtracted from all reactions using the rate of an identical reaction without enzyme present.

Pks13-TE Activity Assay.

Mtb Pks13-TE activity was assessed using a modified version of a previously published fluorescence-based assay that monitors the enzymatic hydrolysis of 4MH by Pks13-TE.26 Given that the thioesterase of Pks13 catalyzes the transfer of an acyl group to trehalose, we found that the addition of trehalose to the reaction mixture increased the signal-to-noise ratio (the KM of trehalose was experimentally determined to be 56.6 ± 7.9 mM).24 Therefore, the modified assay now monitors acyl transfer of heptanoic acid from 4MH to trehalose to produce a fluorescent molecule of 4-methylumbelliferyl and a molecule of heptanoate-trehalose. Each reaction mixture contained 1 μM enzyme, 75 mM trehalose, 1% (v/v) DMSO, or the corresponding inhibitor and each reaction initiated by addition of 50 μM 4MH (5 mM stock in DMSO). All reactions were performed in triplicate at 37 °C in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) using a λex of 360 nm and a λemit of 450 nm. Relative fluorescence intensities were measured every 30 s on a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek). From all reactions, background hydrolysis of 4MH was subtracted using the identical reactions without the enzyme present.

Initial Inhibition Screening.

THL and stereoderivatives were set at a working stock concentration of 30 mM in DMSO. For initial screening at 100 μM, inhibitors were diluted to 10 mM in DMSO. Reaction components are given above for each respective enzyme. Upon addition of inhibitor to a reaction master mix sufficient for eight reactions, triplicate reactions were quickly aliquoted into a black 384-well plate, the respective fluorophore (RfB for Ag85C or 4MH for Rv3802 and Pks13-TE) was titrated, and relative fluorescence intensities were acquired every 30 s for 10 min. This was considered time point “0 min”. For the “60 min” time point, the enzyme was incubated with the inhibitor at room temperature for 60 min. Triplicate reactions were again aliquoted from the starting master mix, and the enzymatic reaction was initiated with addition of RfB or 4MH and followed by fluorescent monitoring of the reaction. Reaction rates were assessed from time points 2 to 6 min, using a linear fit. Following background rate subtraction, the percent enzymatic activity was calculated using (vi/v0) × 100, where vi is equal to the reaction rate of the inhibited enzyme and v0 represents the uninhibited, steady state reaction rate of the DMSO-only control. Triplicate data were plotted and analyzed using Prism 7.

Ag85C kinact/KI Determination.

To determine kinact/KI values for THL and 2′-epi-THL, inhibitors were serially diluted with DMSO from 30 to 1.25 mM (final reaction concentrations from 300 to 12.5 μM). Reaction components are given above for Ag85C. A master mix solution of enzyme, trehalose, and buffer was aliquoted into a black 384-well plate followed by the addition of the respective concentration of inhibitor in triplicate. RfB was immediately titrated into reaction mixtures and the relative fluorescence intensity acquired every 30 s for 40 min. Following background subtraction and conversion of relative florescence units to the concentration of product (resorufin) using a resorufin standard curve (from 0.1 to 6.0 μM), triplicate data were plotted using Prism 7. The kobs values were determined by fitting the progress curves from time points 0 to 40 min with the equation [P] = (vi/kobs)(1 – exp−kobst), where [P] is the product concentration, vi is the inhibited rate, kobs is the pseudo-first-order rate constant, and t is the time.29 Progress curves fit with this equation are given in Figure S2. The determined kobs values were then plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration and fitted with the equation kobs = kinact/(1 + KI/[I]) to calculate kinact/KI values.29 The data were plotted and fit using Prism 7. The determined kinact/KI value for THL is within experimental error of our previously reported value of (7.9 ± 1.0) × 10−3 μM−1 min−1 determined using purchased THL.18

Rv3802 Inhibition and EC50 Determination.

Inhibition of Rv3802 by THL was assessed by evaluating reaction progress curves of the enzyme titrated with THL for time-dependent inhibition. Initially, THL was diluted from 30 mM to 10 μM in DMSO and further serially diluted to 0.625 μM (final reaction concentration from 100 to 6.25 nM THL). A master mix of 50 nM enzyme (increase from value given above) and buffer was aliquoted into black 384-well plates followed by titration of serially diluted THL in triplicate. Immediately after addition of THL, 4MH was added and the relative fluorescence intensities were measured every 30 s for 10 min. Following background subtraction, the resulting triplicate data were plotted in Prism 7. Progress curves are shown in Figure S3.

To evaluate the Kmapp for THL and the “epi” derivatives, the respective inhibitor at 10 μM in DMSO (final reaction concentration of 100 nM) was titrated into 20 nM Rv3802 followed by immediate titration of 4MH. The reaction was fluorescently monitored for 20 min, with fluorescence intensities acquired every 30 s. Following background subtraction, data were plotted in Prism 7 and fit with a linear function for the first 4 min of the reaction. The equation used to calculate the Kmapp is , where k1 and K1 are the known kcat and Km values for 4MH, respectively, and K2 is the Kmapp for the β-lactone being tested.

EC50 values were determined through the titration of serially diluted THL or the respective derivatives into an aliquoted master mix of enzyme and buffer (same reaction conditions listed for activity assays). THL and “epi” stereoderivatives were diluted to 60 μM with DMSO and serially diluted to 0.625 μM (the final reaction concentrations ranged between 600 and 6.25 nM). For “ent” stereoderivatives, the 30 mM stocks were serially diluted to 3.125 mM (the final reaction concentration range was from 300 to 3.125 μM). Following titration of the respective derivative concentrations, kinetic reactions were immediately initiated by titration of 4MH and relative fluorescence intensities measured every 30 s for 20 min. A linear rate was fit to data between time points 2 and 6 min. Following background subtraction, the percent enzymatic activity was determined using the equation (vi/vs) × 100, where vi is the inhibited reaction rate and vs represents the uninhibited, steady state reaction rate of the DMSO-only control. The percent enzymatic activity was plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration, and EC50 values were determined by fitting the data using a variable slope model represented by the equation y = 100/(1 + xHill slope/EC50Hill slope) in Prism 7 (EC50 curves are given in Figure S4).

Pks13-TE Reversible Covalent Inhibition and Influence of Trehalose.

To investigate concentration and time dependence, THL was set at a working stock concentration of 5 mM in DMSO and serially diluted to give desired concentrations. Three different THL concentrations ranging from 50 to 12.5 μM were tested by adding the respective amounts of THL to a reaction master mix sufficient for triplicate reactions, taken every hour for 4 h. Upon titration of THL to the master mix containing enzyme, trehalose, and buffer, reactions were quickly aliquoted into the wells of a black 384-well plate and the increase in relative fluorescence intensity was measured immediately following addition of 4MH. This was considered time point “0 min”. Kinetic experiments were conducted every hour by aliquoting more reaction master mix, and again reactions were initiated upon titration of 4MH. The percent enzymatic activity was calculated as (vi/vs) × 100, where vi is the inhibited rate and vs is the uninhibited steady state rate of the DMSO control, following background rate subtraction. Data were plotted in Prism 7.

To investigate the influence of trehalose on THL inhibition, trehalose was removed from the standard activity assay master mix and reactions without were compared to reactions with trehalose added. For each set, a master mix with a volume sufficient for 15 triplicate reactions, taken every 30 min, was used. Kinetic experiments were initiated as described above. Again, enzymatic activity was assessed as described above, and it should be noted that two sets of controls were used to determine the respective vs, one reaction with enzyme, DMSO, and trehalose and another with only enzyme and DMSO. Data were plotted as the percent enzymatic activity as a function of time in Prism 7. “On” rates were determined by fitting data points corresponding to decreasing percent enzymatic activity as a function of time with a linear fit, whereas “off” rates were determined by fitting data points corresponding to increasing percent enzymatic activity as a function of time with a linear fit.

Rv3802 THL Modeling.

The atomic coordinates for Rv3802 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 5W95] and serine THL from the Ag85C–THL structure (PDB entry 5VNS) were obtained from the PDB.18,27 Solvent and ligand molecules were removed from the Rv3802 structure, and the serine THL was aligned with the serine nucleophile and lipid-binding site of Rv3802 using PyMOL.30 Resulting coordinates were inserted into the Rv3802 PDB file in place of the catalytic serine. Rotatable bonds of the peptidyl arm were manually adjusted in COOT to fit within the solvent channel of Rv3802, and the resulting model was subjected to simple model perturbation using Phenix Dynamics.31,32

■ RESULTS

Initial Inhibition Screen.

The following THL stereoderivatives were tested as follows: 2′-epi, 5-epi, and 2′,5-epi being epimers of the respective centers of THL and their subsequent enantiomers (ent1, enantiomer of THL; ent2, enantiomer of 2′-epi; ent3, enantiomer of 5-epi; ent4, enantiomer of 2 ′,5-epi). THL carbon centers are numbered in Figure 1A and structures given in Figure S1. The inhibition potential of THL and its stereoderivatives was evaluated by screening each of the three targeted enzymes against the respective inhibitor at 100 μM. To initially assess time-dependent covalent inhibition, inhibitors were screened with a 0 or 60 min preincubation period prior to initiating kinetic experiments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Resulting percent enzymatic activity of Ag85C, Rv3802, and Pks13-TE following treatment with the respective THL stereoderivative at 100 μM for 0 and 60 min.

Ag85C displays a high level of stereoselectivity preference toward THL. The only stereoderivative of THL that substantially inhibits Ag85C is 2′-epi-THL, which is the stereoderivative most structurally similar to THL. Initial inhibition levels are 31.8 ± 5.9 and 35.8 ± 2.2% for THL and 2′-epi-THL, respectively, when compared to the uninhibited control. However, inhibition levels increased substantially for both inhibitors following a 1 h incubation period, resulting in a nearly complete loss of enzymatic activity in both cases. Time-dependent inhibition is also observed for all other stereoderivatives but at lower levels of inherent inhibition. Specifically, the inhibition level of 5-epi-THL increases from 12.3 ± 2.6 to 57.8 ± 1.6% following a 1 h preincubation, when compared to that of the uninhibited control. A noticeable trend is apparent with regard to generally lower levels of inhibition for ent1-THL, ent2-THL, ent3-THL, and ent4-THL when compared to those of the respective stereoisomers.

At 100 μM THL, 2′-epi-THL, 5-epi-THL, and 2′,5-epi-THL all completely inhibit Rv3802 with no preincubation time. However, the enantiomers of these derivatives show lower levels of inhibition, 85.1 ± 1.4, 83.9 ± 0.6, 83.0 ± 2.9, and 79.0 ± 1.7% for ent1-THL, ent2-THL, ent3-THL, and ent4-THL, respectively. Minor, time-dependent inhibition is observed for the “ent” derivatives as inhibition levels increase between 4 and 6% for these four derivatives given a 1 h preincubation period when compared to those of the uninhibited control reactions.

Similar to Rv3802, the thioesterase domain of Pks13 was relatively nonstereospecific with regard to THL inhibition. Inhibition levels for THL and “epi” derivatives at 100 μM were between 50 and 60% at time point zero, with levels of inhibition increasing slightly as a function of time. THL, epi derivatives, and ent2-THL all reduced Pks13-TE activity to ~30% when compared to the values of uninhibited reactions following a 1 h preincubation. Ent2-THL displayed the largest increase in the level of inhibition following a 1 h incubation. However, the other “ent” derivatives again displayed lower levels of inhibition as observed with Ag85C and Rv3802.

Ag85C Inhibition.

As stated above, the only stereoderivative that displayed significant inhibition comparable to that of THL was 2′-epi-THL. Our previous work with Ag85C and THL indicated that the acyl–enzyme (THL–Ag85C) complex was considerably more stable than the complex of THL and FAS.18 In fact, diffraction quality crystals were obtained using only a 1:1.2 enzyme:THL molar ratio, highlighting that the covalent Ag85C–THL complex is irreversible.18 Because of the lack of observable hydrolysis of the covalent complex, THL inhibition for Ag85C was previously characterized as an irreversible inhibitor using a kinact/KI analysis.18 Given that covalent inhibition is dependent on both concentration and time, this enzymatic analysis quantifies both components of inhibition.29 Therefore, an identical approach was used to assess the difference in binding affinity and the rate of covalent inhibition between THL and 2′-epi-THL. The kinact/KI values for THL and 2′-epi-THL were experimentally determined to be (4.2 ± 0.7) and (1.1 ± 0.3) × 10−3 μM−1 min−1, respectively (Figure 3). Covalent inhibition occurs at a similar rate between THL and 2′-epi-THL. However, the difference in stereochemistry of the formamide moiety at carbon 2′ results in an ~4.5-fold lower binding affinity, which translates to an ~4-fold lower kinact/KI value for 2′-epi-THL compared to that of THL.

Figure 3.

kinact/KI plot for THL and 2′-epi-THL. While inhibition occurs at a similar rate (kinact), Ag85C has a lower affinity (KI) for 2′-epi-THL than for THL, resulting in a lower kinact/KI value. Triplicate data are plotted, and the mean value is shown with error bars given. Reaction progress curves used for kobs determination are given in Figure S2.

Rv3802 Inhibition.

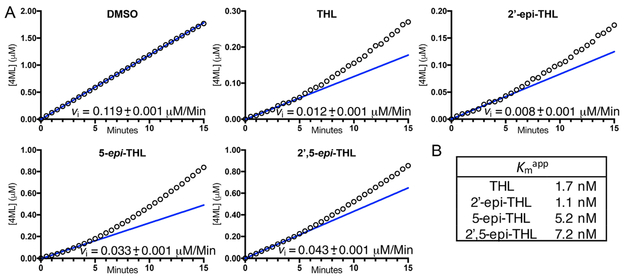

Initial screening of Rv3802 at higher concentrations of THL suggests inhibition is relatively nonstereospecific; however, there was a noticeable difference when the stereocenters at carbons 2 and 3 were changed. Given that Rv3802 is a serine esterase and was previously identified to be covalently modified by a THL probe, THL inhibition is therefore believed to be covalent.10,22 When THL was titrated into Rv3802 at concentrations ranging from 100 to 6.25 nM with no preincubation period, reaction velocities decreased over the span of 10 min, even for those reaction mixtures including a slight excess of THL. However, the inhibited steady state rate did not reach zero, which contrasts with what one would anticipate with an irreversible covalent inhibitor (Figure S3).29 When THL, 2′-epi-THL, 5-epi-THL, and 2′,5-epi-THL were tested at a 5:1 inhibitor:enzyme molar ratio and monitored over a longer time period, a similar phenomenon was observed (Figure 4). The initial reaction velocities were linear during the first 5 min of the reaction; however, the reaction velocities for all four inhibitors then began to increase over the following 10–15 min (Figure 4). This increase in reaction velocities was more evident with the 5-epi-THL and 2′,5-epi-THL stereoderivatives than with THL and 2′-epi-THL. The resulting progress curves therefore suggest that THL and its “epi” derivatives react with Rv3802 but the formed acyl–enzyme intermediates are subject to almost immediate hydrolysis. The apparent catalytic turnover therefore decreases the overall concentration of the “active” inhibitor in the reaction, allowing for rescue of enzymatic activity. Therefore, a kinact/KI analysis was not appropriate, as inhibition is not observed to be irreversible. Instead, the vi values were used to obtain the Kmapp for each of the tested compounds.

Figure 4.

Reaction progress curves of Rv3802 inhibition by THL and “epi” stereoderivatives. (A) Initial velocities for Rv3802 activity in the presence of THL and three of the “epi” stereoderivatives. The time-dependent increase in vi when the enzyme reacts with a 5:1 inhibitor:enzyme molar ratio suggests catalytic hydrolysis of the β-lactone form of the tested compounds. Linear fits are to the first 4 min of the reaction. All progress curves are shown as the average of triplicate reactions. (B) Kmapp values determined from linear fits for THL and each of the “epi” stereoderivatives.

To further compare inhibition of Rv3802 by THL and its stereoderivatives, EC50 values were determined using linear reaction rates over time points from 2 to 6 min with uninhibited and inhibited reaction mixtures containing 20 nM Rv3802. Determined EC50 values for all stereoderivatives are listed in Table 1, and EC50 curves can be found in Figure S4. 2′-epi-THL was found to have the best EC50 value of 9.2 ± 0.5 nM; however, THL, 2′-epi-THL, 5-epi-THL, and 2′,5-epi-THL all have comparable EC50 values in the low nanomolar (9.2–28.7 nM) concentration range. Note that the determined EC50 values are generally consistent with the Kmapp values determined in Figure 4, with 5-epi-THL exhibiting a lower than expected EC50 in relation to the Kmapp determined in Figure 4. Interestingly, the “ent” series of derivatives possess EC50 values that are 3 orders of magnitude worse. These range from 15.9 to 62.1 μM. However, there is a correlation between the “epi” series and their respective enantiomers given that 2′,5-epi-THL and its respective enantiomer, ent4-THL, have the highest EC50 values relative to those of the other “epi” and corresponding “ent” stereoderivatives.

Table 1.

Determined EC50 Values for THL and the THL Stereoderivatives Using 20 nM Rv3802 a

| inhibitor | EC50 |

|---|---|

| THL | 16.2 ± 0.8 nM |

| 2′-epi-THL | 9.2 ± 0.5 nM |

| 5-epi-THL | 12.6 ± 1.2 nM |

| 2′,5-epi-THL | 28.7 ± 3.1 nM |

| ent1-THL | 15.9 ± 1.0 μM |

| ent2-THL | 15.9 ± 1.1 μM |

| ent3-THL | 16.6 ± 0.9 μM |

| ent4-THL | 62.1 ± 4.1 μM |

Corresponding EC50 curves are depicted in Figure S4.

Pks13-TE Inhibition.

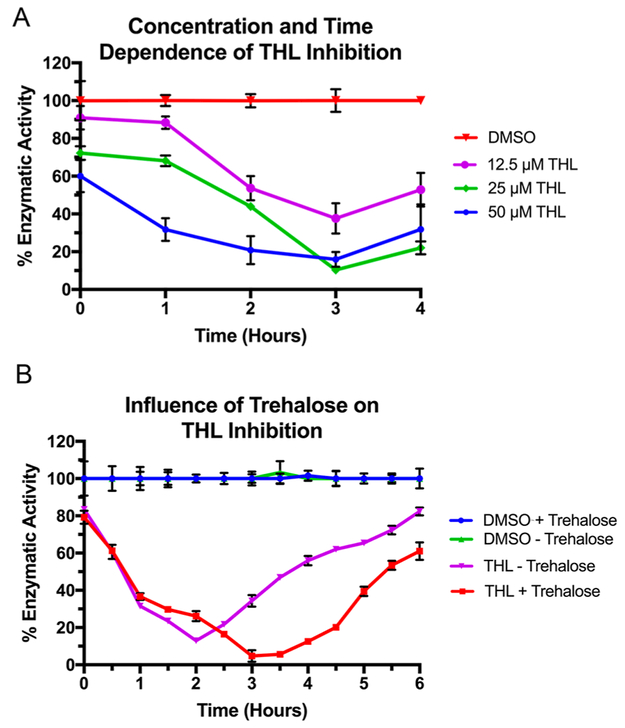

Initial screening of Pks13-TE indicated THL inhibition to be time-dependent and relatively nonstereospecific (Figure 2). Because of the nonstereospecific inhibition and an abundance of THL over other stereoderivatives, concentration and time dependence was evaluated further using only THL. Indeed, inhibition was shown to be dependent on concentration and time upon varying the THL concentration and monitoring enzymatic activity over a time course much longer than that used for the other two enzymes (Figure 5A). Following incubation with THL for 3 h, inhibition levels of Pks13-TE continued to increase (Figure 5A). From 0 to 3 h, inhibition levels increased 44.1 ± 3.5, 61.8 ± 3.5, and 62.3 ± 5.0%, for 50, 25, and 12.5 μM THL, respectively, when compared to that of the uninhibited control. However, at 4 h, the trend for inhibition levels was reversed and they decreased to 16.0 ± 2.1, 11.6 ± 0.4, and 15.2 ± 1.4%, respectively (Figure 5A). As seen for Rv3802, the THL–enzyme adduct was being catalytically turned over.

Figure 5.

Time-, concentration-, and trehalose-dependent inhibition of Pks13. (A) Covalent inhibition of Pks13-TE by THL occurs slowly and is prone to catalytic turnover. (B) The presence of trehalose prolongs the inactivation by THL but increases the rate of enzymatic recovery. Data are plotted in triplicate; the mean value is shown with error bars given, and lines connecting points are given for the sake of clarity and were not used for rate determinations.

To investigate this further, a longer time course was used. Additionally, given that the thioesterase domain of Pks13 facilitates the acyl transfer of β-keto-mycolic acid to trehalose, the effect of trehalose on THL inhibition was also of interest.24 The presence of trehalose slowed the rate of inactivation of Pks13-TE by 48 ± 6.7% (Figure 5B). When trehalose was removed from the reaction mixture, recovery of enzymatic activity occurred almost 1 h earlier (Figure 5B). However, the recovery rate of enzymatic activity was 23.8 ± 2.4% faster with trehalose present (Figure 5B). Trehalose therefore decreases the initial rate of covalent inhibition of Pks13-TE while increasing the rate of hydrolysis of the acyl–enzyme covalent complex, which allows for recovery of enzymatic activity.

■ DISCUSSION

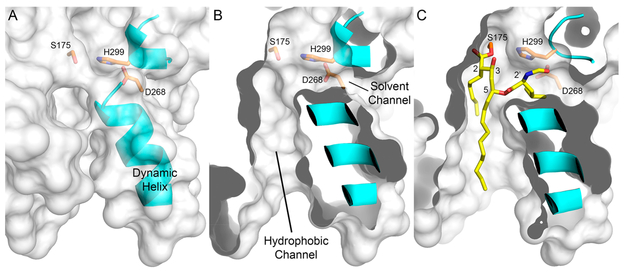

Initial screening of Ag85C against the THL stereoderivatives indicated the enzyme to be highly stereospecific with regard to THL (Figure 2). These findings are surprising given the apo Ag85C structure displays a large, hydrophobic cleft adjacent to the catalytic residues on the surface of the protein (Figure 6A).25 The hydrophobic cleft is thought to be the mycolic acidbinding site and therefore should readily accommodate a variety of THL diastereomers given the large size of mycolic acid.18,33,34 The alkyl chains of THL occupy this hydrophobic cleft as observed in the Ag85C–THL X-ray structure (Figure 6B).18 The Ag85C–THL structure highlights the fact that THL binds in a shape-complementary manner to the enzyme after covalent modification, which possesses a hydrophobic pocket that is larger than the analogous pocket in the apo form of Ag85C.18 However, a change in stereochemistry at C2′ on the peptidyl arm reduces the binding affinity as observed in the 2′-epi-THL stereoderivative (Figure 3), yet this change in stereochemistry does not appear to influence the irreversible nature of the covalent acyl7–enzyme complex, most likely because H260 is displaced in a manner similar to that of THL (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Ag85C structural forms. (A) A large hydrophobic cleft adjacent the active site is apparent in the apo Mtb Ag85C X-ray crystal structure, with the catalytic residues colored orange (PDB entry 1DQZ).25 The hydrophobic cleft is thought to be the mycolic acidbinding site of Ag85C.18 (B) The X-ray crystal structure of Ag85C in a covalent complex with THL (yellow) allows for the molecular assessment of observed stereoselective inhibition by THL and the resulting stability of the acyl–enzyme complex through displacement of the catalytic H260 (PDB entry 5VNS).18

Given the stereoselective inhibition of Ag85C observed in this study, these results suggest that the initial binding of THL to Ag85C is highly shape-specific. This is best illustrated when the stereochemistry of C5 is switched. This change in stereochemistry would likely position the peptidyl side arm into the hydrophobic cleft where the palmitic tail resides when using THL, reducing the initial binding affinity of the 5-epi-THL stereoderivative (Figure 6B). Indeed, a significant decrease in inhibition level is observed with the 5-epi-THL stereoderivative. In addition, when the stereocenters are swapped at the C2 and C3 positions on the β-lactone ring, inhibition of Ag85C is nearly abolished, as observed with the “ent” derivatives. Additionally, lower levels of enzymatic activity are observed after incubation for 1 h, suggesting that these inhibitors also retain their covalent attachment to the enzyme. On the basis of the crystal structure of the Ag85C–THL covalent complex, there is sufficient volume in the active site to accommodate the stereochemical changes to THL.18 However, the lack of apparent inhibition by “ent” derivatives suggests that the stereochemistry of the β-lactone ring with respect to the rest of the THL molecule is highly important for the proper orientation of the carbonyl electrophile of THL for nucleophilic attack. The proper orientation and the structural rigidity of β-lactones are likely the reason why the “ent” series derivatives, which have the same stereochemistry at C2 and C3 as mycolic acid, the natural Ag85C substrate, are poorer inhibitors than those derivatives possessing alternative stereochemistry.13

Inhibition of Rv3802 by THL has been assumed to be covalent; this is supported by the literature showing that it undergoes covalent modification by a THL probe.10,11,22 However, these previous studies failed to fully investigate the stability of the covalent complex. We found that acylation of the active site serine occurs within seconds at low stoichiometric ratios (Figure 4). However, the acyl-linked THL–enzyme adduct is subject to hydrolysis by the enzyme, and the rate of this hydrolysis is indeed influenced by THL stereochemistry (Figure 4). We initially sought to determine the rate of THL turnover; however, we cannot directly monitor the conversion of THL using spectroscopic methods and also observed that Rv3802 begins to lose enzymatic activity after 30 min under assay conditions. Therefore, we could not fully assess the rate of enzymatic recovery or THL turnover.

Because the current data are consistent with Rv3802 promoting catalytic hydrolysis of the covalent THL–enzyme complex and THL acting as an Rv3802 substrate, we ultimately analyzed THL inhibition using two different methods. Treating the β-lactones as competitive substrates is the most appropriate methodology, but β-lactone ring opening does not afford spectroscopic monitoring. Therefore, we also employed methods more typical for evaluating competitive inhibitors. Previous studies have reported low micromolar IC50 values and an apparent KI of 5 nM for THL to Rv3802.11,19,22 Therefore, it is of little surprise that we see almost no enzymatic activity when THL is tested at 100 μM; however, we were still uncertain about how stereochemistry would influence Rv3802 kinetics.11,19,22 Interestingly, all “epi” derivatives (stereo changes to the peptidyl arm) displayed EC50 values in the low nanomolar range, suggesting the enzyme is capable of binding a large variety of structurally diverse THL configurations (Table 1). The EC50 values are consistent with the Kmapp values obtained in the competitive substrate analysis. This suggests that either analysis is reasonable for Rv3802, but more studies are warranted to more thoroughly evaluate the kinetic parameters when using β-lactones as alternative substrates.

The highly dynamic helix that defines the lipid-binding site of the enzyme may allow for a variety of protein conformations upon THL binding (Figure 7A).27 When this helix is in the open conformation, a sizable hydrophobic channel leading to the active site is observed (Figure 7B).27 Modeling THL within the hydrophobic channel required only minor rotational dihedral manipulation and resulted in the peptidyl side arm residing in a solvent channel that is perpendicular to the lipidbinding site (Figure 7C). Positioning of the peptidyl side arm into this channel localizes the arm near the catalytic histidine, H299, and may explain the difference in observed catalytic turnover of the “epi” derivatives and THL (Figure 4 and Table 1). In the case of THL and 2′-epi-THL, the side arm may be partially displacing H299 like the analogous histidine in Ag85C. Alternatively, THL and 2′-epi-THL may be binding in a fashion that allows a stable hydrogen bond to form between H299 and the β-hydroxyl that forms on C3 of THL following covalent complex formation similar to that observed in the THL and FAS enzyme.8 In either scenario, the level of water activation by the catalytic histidine is reduced (Figure 7C).8,9,18 However, when the stereochemistry of the peptidyl arm is changed, 5-epi-THL and 2′,5-epi-THL, the interaction that may otherwise reduce the level of water activation is abolished and hydrolysis of the acyl–enzyme intermediate rapidly occurs, allowing for recovery of enzymatic activity. Additionally, this binding model would explain the inhibition differences observed in a prior study, which synthesized a library of THL peptidyl arm derivatives. Briefly, West et al. found that the smaller the side arm derivative, the better the inhibition; given that the solvent channel is more sterically hindered than the lipid-binding site, this binding mode may explain their reported SAR study.11

Figure 7.

Modeled Rv3802-THL complex. (A) When the dynamic helix of Rv3802 is in the open form, a large hydrophobic channel leading to the catalytic residues (orange) is apparent. This channel is believed to be the fatty acid-binding site for phosphatidylinositol substrates (PDB entry 5W95).27 (B) The Rv3802 surface rendering is clipped to highlight the size of the hydrophobic channel and to show a solvent channel leading to the active site.27 (C) Resulting Rv3802–THL covalent complex model based on stereoderivative inhibition data. THL is readily accommodated within the lipid-binding site and solvent channel of Rv3802.

Despite Rv3802 being able to tightly bind the structurally diverse “epi” THL derivatives, the “ent” derivatives had EC50 values that were 3 orders of magnitude worse. Changes in stereochemistry at C2 and C3 of the β-lactone ring greatly reduce the level of inhibition, which is similar to the inhibitory pattern observed for Ag85C. This stereospecific trend is most likely not based on a form of substrate mimicry, as Rv3802 is believed to perform chemistry on glycerophospholipids, not mycolic acid-containing substrates like Ag85C.21,22,27 This trend would therefore be supported by the previous argument that the stereochemistry of the rigid β-lactone ring is important for proper alignment of the β-lactone ring of THL with the enzyme for nucleophilic attack by the serine nucleophile.

Given that Pks13 was not identified as one of the 261 enzymes modified by THL, we did not anticipate potent inhibition for THL.10 However, we were curious to see if THL could serve as a starting scaffold for the design of a covalent inhibitor toward the thioesterase domain of Pks13. Indeed, THL does slow the Pks13-TE reaction rate by competing with the fluorogenic substrate; however, THL turnover is slow with respect to the rate of the reaction with Rv3802 (Figure 5). Recovery of enzymatic activity after drug incubation for 2 h suggests the covalent THL–Pks13-TE adduct is subject to hydrolysis, which thereby restores enzymatic activity and promotes inactivation of THL as a covalent inhibitor (Figure 5B). Because the thioesterase domain of Pks13 is responsible for the acyl transfer of β-keto-mycolic acid to the 6-hydroxyl moiety of trehalose, we were curious to determine if the THL inhibitory kinetics were more reflective of the irreversible inhibition of Ag85C or the short-lived covalent complex formed with Rv3802.24 Interestingly, the inhibition of Pks13-TE is more like that of Rv3802; however, in contrast to Rv3802, which exhibits rapid hydrolysis of the covalent THL–Rv3802 complex, Pks13-TE retains the covalent coupling with THL at least 10-fold longer. Intriguingly, in the presence of trehalose, THL inhibition of Pks13-TE is slower, yet restoration of enzymatic activity is accelerated (Figure 5B). Therefore, the observed enzymatic trend may suggest that trehalose competes with THL for entry to the active site, thereby slowing the formation of the initial covalent complex with Pks13-TE. However, once the acyl–enzyme complex is formed, trehalose may be positioned within the active site for nucleophilic activation and function as an acyl acceptor. This would therefore suggest that in the presence of trehalose, recovery of enzymatic activity might be the result of acyl transfer over acyl hydrolysis of the THL–enzyme covalent complex. Regardless of whether acyl transfer is occurring, inhibition via THL has shown that compounds containing β-lactones can serve as transient covalent inhibitors of the Pks13-TE domain that are subject to catalytic turnover.

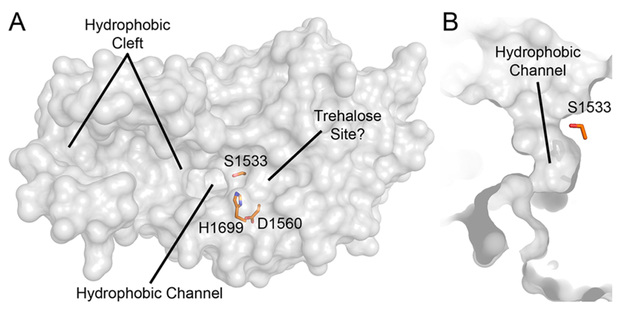

With regard to stereospecificity, the trend of “ent” derivatives (a change in the stereocenter of the β-lactone ring) exhibiting inhibitory properties less potent than those of the “epi” series is also observed in the case of Pks13-TE, sans ent2-THL. Overall, THL inhibits Pks13-TE with little regard to stereochemistry. This lack of stereospecificity toward THL may be a result of the large, solvent-exposed active site of Pks13-TE (Figure 8A).26 Additionally, a hydrophobic channel runs through the protein, leading to the catalytic serine (Figure 8B).26 Therefore, the lack of stereospecificity may be attributed to multiple binding modes, which could also explain the modest inhibition levels observed upon immediate titration of Pks13-TE with THL and the tested stereoderivatives. However, stereospecificity for overall THL inhibition may change in the context of full-length Pks13 when the other four domains are present.

Figure 8.

Pks13-TE surface model with active site residues colored orange (PDB entry 5V3W).26 (A) Multiple orientations of binding of THL to the thioesterase domain of Pks13 are possible because of the large hydrophobic cleft and channel present. The presence of trehalose impedes THL inhibition, suggesting a shared binding site or an influence on hydrolysis of the covalent complex. (B) Hydrophobic channel leading from the solvent to catalytic S1533.

The stereochemistry of THL is clearly important with regard to the inhibition of the tested lipid esterases/transferases of Mtb. However, it is not the direct result of simple mycolic acid mimicry as the preferred stereochemistry of THL is the opposite of that of the hallmark mycobacterial lipid. Mostly, the stereochemistry of the β-lactone ring of THL was found to be highly important for cross enzyme covalent complex formation, and this efficacy is likely due to the proper positioning of the covalent warhead for nucleophilic attack by the enzyme. However, the hexanoyl tail and palmitic core of THL most likely afford general affinity for the lipid-binding sites of various lipid esterases. On the basis of this study, a major limitation of the THL scaffold and β-lactone-based inhibitors is the catalytic turnover ability of the inhibited acyl–enzyme adduct. Upon hydrolysis of the acyl–enzyme intermediate, THL is rendered inactive for further covalent inhibition of other serine esterases. THL neutralization via ring opening is analogous to neutralization of potent β-lactam compounds by β-lactamases and carbapenemases.3,4,35,36 Therefore, to increase the efficacy of β-lactone-based inhibitors, the stability of the covalent complex needs to be addressed. One way to address this may be through the manipulation of the peptidyl side arm to displace the catalytic histidine in a fashion similar to that of the Ag85C–THL complex. In conclusion, THL inhibition of these respective enzymes has been further characterized and provides a stereospecific basis for the inhibition of three essential Mtb lipid esterases by THL. These findings can be utilized to further develop the THL scaffold for these enzyme targets with regard to selectivity, potency, and hydrolytic neutralization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by National Science Foundation Grant CHE-1565788 to G.A.O. and National Institutes of Health Grant AI105084 to D.R.R.

Footnotes

■ ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:10.1021/acs.bio-chem.8b00152.

Progress curves used to determine kobs for Ag85C kinact/KI inhibition and the determined EC50 curves for Rv3802 (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

■ REFERENCES

- (1).Borgström B (1988) Mode of action of tetrahydrolipstatin: a derivative of the naturally occurring lipase inhibitor lipstatin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Lipids Lipid Metab 962, 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Heck AM, Yanovski JA, and Calis KA (2000) Orlistat, a new lipase inhibitor for the management of obesity. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 20, 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, and Blanchard JS (2009) Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 323, 1215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dhar N, Dubée V, Ballell L, Cuinet G, Hugonnet JE, Signorino-Gelo F, Barros D, Arthur M, and McKinney JD (2015) Rapid cytolysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by faropenem, an orally bioavailable β-lactam antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 59, 1308–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kridel SJ, Axelrod F, Rozenkrantz N, and Smith JW (2004) Orlistat is a novel inhibitor of fatty acid synthase with antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 64, 2070–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Menendez J, Vellon LA, and Lupu R (2005) Antitumoral actions of the anti-obesity drug orlistat (Xenical) in breast cancer cells: blockade of cell cycle progression, promotion of apoptotic cell death and PEA3-mediated transcriptional repression of Her2/neu (erb B-2) oncogene. Ann. Oncol 16, 1253–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kuhajda FP (2006) Fatty acid synthase and cancer: new application of an old pathway. Cancer Res. 66, 5977–5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pemble CW, Johnson LC, Kridel SJ, and Lowther WT (2007) Crystal structure of the thioesterase domain of human fatty acid synthase inhibited by Orlistat. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fako VE, Zhang JT, and Liu JY (2014) Mechanism of orlistat hydrolysis by the thioesterase of human fatty acid synthase. ACS Catal. 4, 3444–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ravindran MS, Rao SP, Cheng X, Shukla A, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Yao SQ, and Wenk MR (2014) Targeting lipid esterases in mycobacteria grown under different physiological conditions using activity-based profiling with tetrahydrolipstatin (THL). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 435–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).West NP, Cergol KM, Xue M, Randall EJ, Britton WJ, and Payne RJ (2011) Inhibitors of an essential mycobacterial cell wall lipase (Rv3802c) as tuberculosis drug leads. Chem. Commun 47, 5166–5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jackson M (2014) The mycobacterial cell envelope—Lipids. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med 4, a021105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Marrakchi H, Laneelle MA, and Daffe M (2014) Mycolic acids: structures, biosynthesis, and beyond. Chem. Biol. 21, 67–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mulzer M, Tiegs BJ, Wang Y, Coates GW, and O’Doherty GA (2014) Total synthesis of tetrahydrolipstatin and stereoisomers via a highly regio-and diastereoselective carbonylation of epoxyhomoallylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10814–10820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu X, Wang Y, Duclos RA Jr, and O’Doherty GA (2018) Stereochemical structure activity relationship studies (S-SAR) of Tetrahydrolipstatin. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 9, 274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jackson M, Raynaud C, Laneelle M-A, Guilhot C, Laurent-Winter C, Ensergueix D, Gicquel B, and Daffe M (1999) Inactivation of the antigen 85C gene profoundly affects the mycolate content and alters the permeability of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope. Mol. Microbiol 31, 1573–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Belisle JT, Vissa VD, Sievert T, Takayama K, Brennan PJ, and Besra GS (1997) Role of the Major Antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Cell Wall Biogenesis. Science 276, 1420–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Goins CM, Dajnowicz S, Smith MD, Parks JM, and Ronning DR (2018) Mycolyltransferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in covalent complex with tetrahydrolipstatin provides insights into Antigen 85 catalysis. J. Biol. Chem 293, 3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Parker SK, Barkley RM, Rino JG, and Vasil ML (2009) Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3802c encodes a phospholipase/thioesterase and is inhibited by the antimycobacterial agent tetrahydrolipstatin. PLoS One 4, e4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).West NP, Chow FM, Randall EJ, Wu J, Chen J, Ribeiro JM, and Britton WJ (2009) Cutinase-like proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: characterization of their variable enzymatic functions and active site identification. FASEB J 23, 1694–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Meniche X, Labarre C, De Sousa-D’Auria C, Huc E, Laval F, Tropis M, Bayan N, Portevin D, Guilhot C, Daffé M, and Houssin C (2009) Identification of a stress-induced factor of Corynebacterineae that is involved in the regulation of the outer membrane lipid composition. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7323–7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Crellin PK, Vivian JP, Scoble J, Chow FM, West NP, Brammananth R, Proellocks NI, Shahine A, Le Nours J, Wilce MC, Britton WJ, Coppel RL, Rossjohn J, and Beddoe T (2010) Tetrahydrolipstatin inhibition, functional analyses, and threedimensional structure of a lipase essential for mycobacterial viability. J. Biol. Chem 285, 30050–30060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Portevin D, de Sousa-D’Auria C, Houssin C, Grimaldi C, Chami M, Daffé M, and Guilhot C (2004) A polyketide synthase catalyzes the last condensation step of mycolic acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria and related organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 101, 314–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gavalda S, Bardou F, Laval F, Bon C, Malaga W, Chalut C, Guilhot C, Mourey L, Daffé M, and Quémard A (2014) The polyketide synthase Pks13 catalyzes a novel mechanism of lipid transfer in mycobacteria,. Chem. Biol 21, 1660–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ronning DR, Klabunde T, Besra S, Vissa VD, Belisle JT, and Sacchettini JC (2000) Crystal structure of the secreted form of antigen 85C reveals potential targets for mycobacterial drugs and vaccines. Nat. Struct. Biol 7, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Aggarwal A, Parai MK, Shetty N, Wallis D, Woolhiser L, Hastings C, Dutta NK, Galaviz S, Dhakal RC, Shrestha R, et al. (2017) Development of a novel lead that targets M. tuberculosis Polyketide Synthase 13. Cell 170, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Goins CM, Schreidah CM, Dajnowicz S, and Ronning DR (2018) Structural basis for lipid binding and mechanism of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3802 phospholipase. J. Biol. Chem 293 (4), 1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Favrot L, Grzegorzewicz AE, Lajiness DH, Marvin RK, Boucau J, Isailovic D, Jackson M, and Ronning DR (2013) Mechanism of inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85 by ebselen. Nat. Commun 4, 2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Copeland RA (2005. Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitors in Drug Discovery, John Wiley & Sons. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.6, Schrödinger, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Anderson DH, Harth G, Horwitz MA, and Eisenberg D (2001) An interfacial mechanism and a class of inhibitors inferred from two crystal structures of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 30 kDa major secretory protein (Antigen 85B), a mycolyl transferase. J. Mol. Biol 307, 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ronning DR, Vissa V, Besra GS, Belisle JT, and Sacchettini JC (2004) Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85A and 85C structures confirm binding orientation and conserved substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem 279, 36771–36777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Soroka D, Li de La Sierra-Gallay I, Dubée V, Triboulet S, Van Tilbeurgh H, Compain F, Ballell L, Barros D, Mainardi J-L, Hugonnet J-E, and Arthur M (2015) Hydrolysis of clavulanate by Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-lactamase BlaC harboring a canonical SDN motif. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 59, 5714–5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Cohen KA, El-Hay T, Wyres KL, Weissbrod O, Munsamy V, Yanover C, Aharonov R, Shaham O, Conway TC, Goldschmidt Y, Bishai WR, and Pym AS (2016) Paradoxical hypersusceptibility of drug-resistant mycobacteriumtuberculosis to β-lactam antibiotics. EBioMedicine 9, 170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.