Abstract

The P38MAPK pathway participates in regulating cell cycle, inflammation, development, cell death, cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. Genetic variants of some genes in the P38MAPK pathway are reportedly associated with lung cancer risk. To substantiate this finding, we used six genome-wide association studies (GWASs) to comprehensively investigate associations of 14,904 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 108 genes of this pathway with lung cancer risk. We identified six significant lung cancer risk-associated SNPs in two genes (CSNK2B and ZAK) after correction for multiple comparisons by a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.20. After removal of three CSNK2B SNPs that are located on the same locus previously reported GWAS, we performed LD analysis, SNP functional prediction and further analysis for two independent SNPs: rs3769201 and rs722864 in ZAK. We also expanded the analysis by including these two SNPs from additional GWAS datasets of Harvard University (984 cases and 970 controls) and deCODE (1,319 cases and 26,380 controls). The overall effects of these two SNPs were assessed using all eight GWAS datasets (OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.89–0.95, and P=1.03E-05 for rs3769201; OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.88–0.95, and P=2.03E-06 for rs722864). Finally, we performed an eQTL analysis and found that these two SNPs were significantly associated with ZAK mRNA expression levels in lymphoblastoid cell lines. In conclusion, the ZAK rs3769201 and rs722864 may be possible functional susceptibility loci for lung cancer risk.

Keywords: lung cancer risk, pathway analysis, ZAK, SNP

Introduction

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among adults worldwide. In the United States, about 224,390 new lung cancer cases will occur in 2016 [1]. Both environmental and genetic factors contribute to the risk of lung cancer. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common genetic variants that are found to be associated with cancer risk, including lung cancer [2, 3]. Although genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified multiple SNPs to be associated with lung cancer risk, most of these SNPs are not biologically plausible. Therefore, we sought to perform a pathway-based analysis with a hypothesis-driven and much fewer SNPs of several published GWAS datasets to reduce the number of candidates. We aim to identify possible functional SNPs that may be associated with lung cancer risk but have not been reported by previous single GWAS analysis. This approach helped us successfully identify additional unreported susceptibility loci in those genes involved in centrosome [4], DNA repair [5], LncRNA [6], and RNA degradation [7]. In the present study, we investigated the associations between genetic variants of genes in the P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (P38MAPK) pathway and lung cancer risk.

The MAP kinase family has four distinct subgroups: extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), c-jun N-terminal or stress-activated protein kinases (JNK/SAPK), ERK/big MAP kinase 1 (BMK1), and P38MAPK. P38MAPK in response to stress stimuli, such as ultraviolet irradiation, cytokines, and heat shock, are involved in cell cycle, inflammation, development, cell death, cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. Mammalian P38MAPK has four isoforms: α, β, γ, and δ. Numerous genes with multiple cellular functions have been identified as P38MAPK pathway substrates. Many transcription factors including p53, activating transcription factor 1/2/6 (ATF-1/2/6), C/EBP, SRF accessory protein (Sap1), MEF2A, DDIT3, and NFAT can be activated by P38 MAPKs [8–13]. Certain studies also have shown that the lack of P38MAPK functions may lead to cell cycle deficiency and tumorigenesis [14, 15]. On the other hand, some published studies showed that the oncogenic potential of this pathway may lead to tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [16, 17].

Several studies have shown that TP53 [18, 19] and ATM [20] in the P38MAPK signaling pathway are associated with lung cancer risk, but these studies did not include many other candidate genes and SNPs of this pathway. In the present study, we comprehensively investigated associations between genetic variants of possible genes in the P38MAPK pathway and lung cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

We used summary data from the Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung and The International Lung Cancer Consortium (TRICL-ILCCO), included six GWASs of 16,838 controls and 12,160 lung cancer cases. These six GWAS studies included The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center study (MDACC), Institute of Cancer Research study(ICR), National Cancer Institute study(NCI), International Agency for Research on Cancer study(IARC), Toronto study from Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute study (Toronto), and German Lung Cancer study (GLC). The expanded analysis included two additional GWASs from ILCCO: the Harvard Lung Cancer study (Harvard) (984 cases and 970 controls) [21] and the Icelandic Lung Cancer study (deCODE) (1,319 cases and 26,380 controls) [22]. A written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects in the original GWASs. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations for each of the participating institutions, and the present study followed the study protocols approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board.

Selection of Genes and SNPs from the P38MAPK pathway

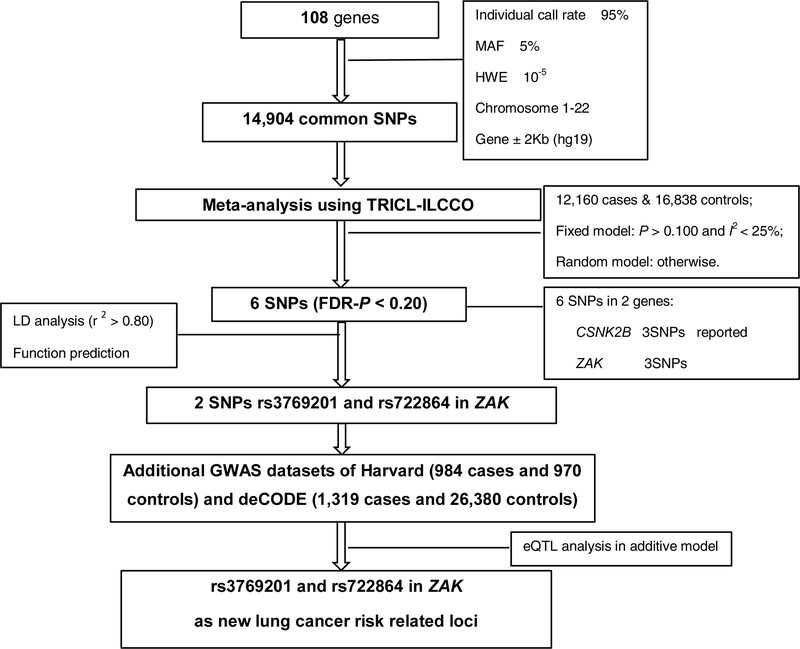

Multiple genotyping platforms were used, including Illumina HumanHap 317, 317+240S, 370Duo, 550, 610 or 1M arrays for all the GWAS datasets. We used IMPUTE2 v2.1.1 [23] or MaCH v1.0 [24] software to perform the imputation of untyped SNPs using the 1000 Genomes Project (phase I integrated release 3, March 2012) as the reference. Genes in the P38MAPK pathway were identified from the Molecular Signatures Database (C2) [25]. Overall, 108 genes located on autosomal chromosomes were selected (details presented in Supplementary Table S1). There were 14,904 SNPs within these selected genes with 2 kb upstream to 2 kb downstream with the following selection criteria: (1) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 5%, (2) genotyping rate ≥ 95%, (3) Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) exact P value ≥ 10-5. The detailed workflow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of SNP selection among the P38MAPK pathway genes

In silico functional prediction and validation

SNPinfo [26], RegulomeDB [27], and HaploReg [28] were used to predict SNP-associated potential functions. The expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis was performed by using the genotyping and expression data available from the lymphoblastoid cell data of 373 European individuals from Genetic European Variation in Health and Disease Consortium (GEUVADIS) and the 1000 Genomes Project (phase I integrated release 3, March 2012) [29]. The TCGA level 3 RNAseq data (LUSC_rnaseqv2_Level_3_RSEM_genes_normalized_data.2016012800.0.0.tar.gz and LUAD_Level_3_RSEM_genes_normalized_data_2016012800.0.0.tar.gz) was obtained from the Broad TCGA GDAC site (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org).

Statistical analysis

We performed an unconditional logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per effect allele by using R (v2.6), Stata (v10, State College, Texas, US) and PLINK (v1.06) for each GWAS data set. A meta-analysis was performed on the selected 14,904 SNPs. We tested heterogeneity among the GWASs by using the Cochran’s Q statistic and investigated the proportion of the total variation by the I2 statistic. When there was no heterogeneity among GWASs (Q-test P > 0.100 and I2 < 25%), we used the fixed-effects model; otherwise, we used the random-effects model. We controlled for multiple testing with a threshold of a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.20. The paired Student t-test was used to test for the differences in gene mRNA expression levels between lung cancer tissue and adjacent normal tissue from the TCGA database. LocusZoom (http://locuszoom.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/) (reference version: 1000 Genomes, Nov 24, 2014; EUR) [30] was employed to generate the regional association plots [31]. The Manhattan plot and LD plots were generated by Haploview v4.2. We used the LD analysis in chosing representative SNPs of ZAK. All other analyses were conducted with SAS (Version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), unless specified otherwise. All the statistical methods and codes were checked and reproduced by one of the co-authors.

Results

Analysis of the six GWAS datasets

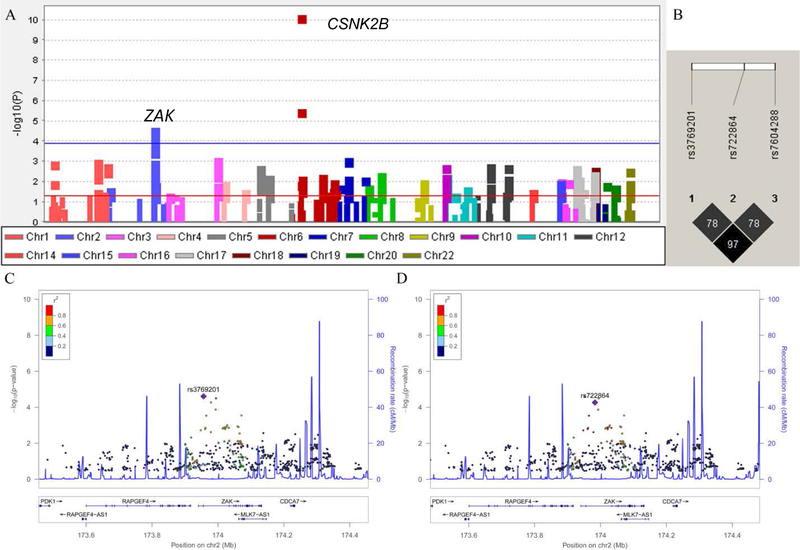

Altogether, 14,904 SNPs from 108 genes were available from the six GWAS datasets of the TRICL-ILCCO consortium. A Manhattan plot demonstrating the associations of SNPs of these genes and lung cancer risk as identified by the single locus analysis can be found in Figure 2A. Overall, six SNPs in two genes (CSNK2B and ZAK) remained significantly associated with lung cancer risk after multiple-testing correction by FDR < 0.20. Their locations and associations with lung cancer risk are presented in Table 1. We excluded three SNPs in CSNK2B, because they are located on the same locus (6p21.33) previously reported by a GWAS [32]. Based on LD analysis (r2 > 0.80) (Figure 2B) and in silico SNP functional prediction (SNPinfo, RegulomeDB, and HaploReg) (Supplementary Table S2), we chose two representative SNPs: rs3769201 and rs722864 of ZAK for further analyses. Regional association plots for rs3769201 and rs722864 in 500 kb up- and downstream region are shown in Figures 2C and 2D. The regional association plots demonstrated that the top SNP rs3769201 was in high LD with rs7604288 and a medium LD with rs722864. The two representative SNPs of ZAK had no LD with previously reported GWAS loci.

Figure 2.

Screening of SNPs in P38MAPKs pathway. (A) Manhattan plot of genome-wide association results of 14,904 SNPs in 108 P38MAPK pathway genes and lung cancer risk in the TRICL-ILCCO Consortium. SNPs are plotted on the X-axis according to their positions on each chromosome. The association P values with lung cancer risk are shown on the Y-axis (as -log10 (P) values). The horizontal blue line represents FDR threshold 0.20. The horizontal red line represents P value of 0.05; (B) LD plots of the SNPs in ZAK with FDR < 0.20; (C) rs3769201 in ZAK with 500 kb up- and downstream of the gene region. (D) rs722864 in ZAK with 500 kb up- and downstream of the gene region. In (C) and (D), the left-hand y-axis shows the association P value of each SNP, which is plotted as -log10 (P) against chromosomal base pair position; the right-hand y-axis shows the recombination rate estimated from the hg19/1000 Genomes European population.

Table 1.

Associations between six SNPs in the P38MAPK pathway and lung cancer risk with FDR < 0.20 in six GWASs

| SNP | Gene | Chr. | Allelea | Position (hg19) | I2 | EAF | OR (95% CI) | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs114487324 | CSNK2B | 6 | A/G | 31636742 | 20 | 0.11 | 1.20 (1.13–1.28) | 6.31E-11 | 9.41E-07 |

| rs115609040 | CSNK2B | 6 | C/A | 31632134 | 8 | 0.19 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 2.76E-06 | 0.015 |

| rs116442837 | CSNK2B | 6 | G/T | 31633496 | 8 | 0.19 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 2.95E-06 | 0.015 |

| rs3769201 | ZAK | 2 | C/T | 1.74E+08 | 15 | 0.22 | 0.91 (0.88–0.96) | 2.48E-05 | 0.092 |

| rs7604288 | ZAK | 2 | T/G | 1.74E+08 | 0 | 0.22 | 0.92 (0.88–0.95) | 3.21E-05 | 0.096 |

| rs722864 | ZAK | 2 | G/A | 1.74E+08 | 17 | 0.20 | 0.91 (0.87–0.97) | 5.41E-05 | 0.134 |

Chr, chromosome; EAF, effect allele frequency; FDR, false discovery rate; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Reference allele/effect allele.

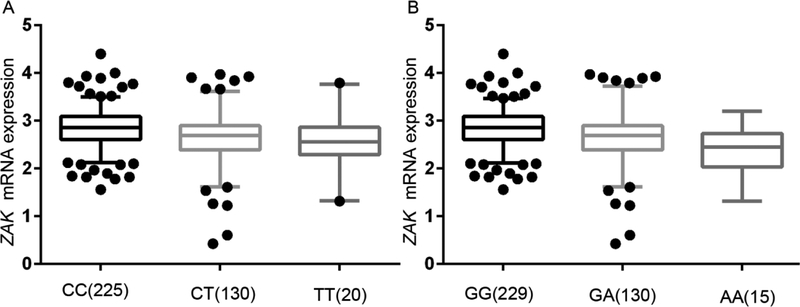

Functional validation by the eQTL analysis

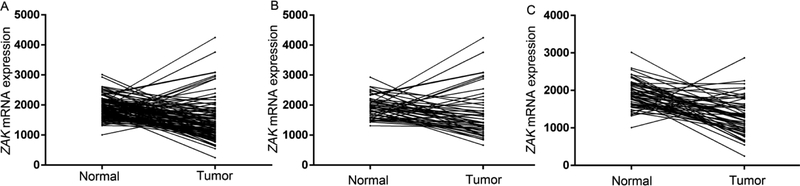

We performed the eQTL analysis to assess the associations between SNPs and their gene mRNA expression levels, and we found that ZAK rs3769201 and rs722864 were associated with ZAK mRNA expression levels in an additive model (Figure 3). ZAK mRNA expression levels significantly decreased with an increased number of the rs3769201T allele in additive (P = 2.86E-04) (Figure 3A). The eQTL analysis results of rs722864 were also significant in an additive model (P = 1.68E-04) (Figure 3B). In addition, we compared mRNA expression levels of ZAK in 109 paired target tissue samples with normal adjacent tissue samples from the TCGA database and found that ZAK mRNA expression levels were also significantly decreased in the tumor tissues compared to the normal tissues (P = 6.29E-08), as well as stratified by adenocarcinoma (AD) and squamous cell lung carcinoma (SC) (Figure 4). Therefore, rs3769201 and rs722864 were chosen as the representative SNPs for further analyses because they were significantly associated with lung cancer risk as assessed in the overall association analysis and had potential functions according to the eQTL analysis.

Figure 3.

The correlations between identified SNPs and ZAK mRNA expression. A, rs3769201 in additive model, P = 2.86E-04; B, rs722864 in additive model, P = 1.68E-04.

Figure 4.

The mRNA expression of ZAK in the 109 paired lung cancer and normal adjacent tissue samples from the TCGA database (A, over all, P = 6.29E-08; B, squamous cell carcinoma, P = 0.069; C, adenocarcinoma, P = 1.55E-09).

Expanded analysis by additional two GWASs

We sought to expand our analysis by two additional independent lung cancer GWASs, Harvard Lung Cancer Study (Harvard) and Icelandic Lung Cancer Study (deCODE). We subsequently performed an overall meta-analysis to evaluate associations between the two ZAK SNPs and lung cancer risk in all eight GWASs. We found the overall effect of these two SNPs from among all eight GWASs remained significant (OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.89–0.95, P value of heterogeneity test (Phet) = 0.471, and P = 1.03E-05 for rs3769201 and OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.88–0.95, Phet = 0.504, and P = 2.03E-06 for rs722864) (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures S1A and S1B).

Table 2.

Associations between two tagSNPs and lung cancer risk stratified by histologic types in eight lung cancer GWASs

| Study | Overall | AD | SC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | OR (95% CI) | P | Case | Control | OR (95% CI) | P | Case | Control | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| rs3769201 C > T | ||||||||||||

| ICR | 1952 | 5200 | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 0.700 | 465 | 5200 | 1.04 (0.89, 1.23) | 0.596 | 611 | 5200 | 0.96 (0.83, 1.11) | 0.591 |

| MDACC | 1150 | 1134 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.218 | 619 | 1134 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.13) | 0.577 | 306 | 1134 | 0.91 (0.73, 1.14) | 0.426 |

| IARC | 2533 | 3791 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) | 0.009 | 517 | 2824 | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) | 0.856 | 911 | 2968 | 0.89 (0.79, 1.02) | 0.088 |

| NCI | 5713 | 5736 | 0.88 (0.83, 0.94) | 1.05E-04 | 1841 | 5736 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) | 4.58E-04 | 1447 | 5736 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.98) | 0.023 |

| Toronto | 331 | 499 | 1.04 (0.81, 1.33) | 0.783 | 90 | 499 | 0.85 (0.58, 1.27) | 0.437 | 50 | 499 | 1.00 (0.61, 1.65) | 0.999 |

| GLC | 481 | 478 | 1.01 (0.81, 1.27) | 0.924 | 186 | 478 | 1.30 (0.97, 1.75) | 0.081 | 97 | 478 | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) | 0.793 |

| Harvard | 984 | 970 | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.802 | 597 | 970 | 1.02 (0.85, 1.21) | 0.868 | 216 | 970 | 0.91 (0.70, 1.19) | 0.513 |

| deCODE | 1319 | 26380 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.02) | 0.124 | 547 | 26380 | 0.95 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.488 | 259 | 26380 | 0.85 (0.67, 1.07) | 0.177 |

| Overall | 14463 | 44188 | 0.92 (0.89, 0.95) | 1.03E-05 | 4862 | 43221 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.401 | 3897 | 43365 | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96) | 0.002 |

| rs722864 G > A | ||||||||||||

| ICR | 1952 | 5200 | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.623 | 465 | 5200 | 1.07 (0.90, 1.26) | 0.461 | 611 | 5200 | 0.97 (0.83, 1.12) | 0.664 |

| MDACC | 1150 | 1134 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.05) | 0.179 | 619 | 1134 | 0.93 (0.78, 1.11) | 0.436 | 306 | 1134 | 0.94 (0.74, 1.19) | 0.604 |

| IARC | 2533 | 3791 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.99) | 0.033 | 517 | 2824 | 1.00 (0.84, 1.18) | 0.982 | 911 | 2968 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.414 |

| NCI | 5713 | 5736 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) | 8.40E-05 | 1841 | 5736 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | 0.001 | 1447 | 5736 | 0.87 (0.78, 0.97) | 0.009 |

| Toronto | 331 | 499 | 1.01 (0.78, 1.33) | 0.915 | 90 | 499 | 0.76 (0.50, 1.16) | 0.207 | 50 | 499 | 1.15 (0.67, 1.98) | 0.609 |

| GLC | 481 | 478 | 1.07 (0.84, 1.35) | 0.585 | 186 | 478 | 1.27 (0.93, 1.73) | 0.136 | 97 | 478 | 0.96 (0.63, 1.47) | 0.855 |

| Harvard | 984 | 970 | 0.88 (0.76, 1.03) | 0.117 | 597 | 970 | 0.90 (0.75, 1.07) | 0.219 | 216 | 970 | 0.76 (0.58, 1.00) | 0.051 |

| deCODE | 1319 | 26380 | 0.90 (0.81, 1.00) | 0.045 | 547 | 26380 | 0.92 (0.78, 1.08) | 0.325 | 259 | 26380 | 0.92 (0.73, 1.17) | 0.498 |

| Overall | 14463 | 44188 | 0.91 (0.88, 0.95) | 2.03E-06 | 4862 | 43221 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 0.139 | 3897 | 43365 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) | 0.004 |

GWAS: genome-wide association study; AD, adenocarcinoma; SC, squamous cell carcinoma; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

In subgroup analysis by histology (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S1), we found that the rs3769201T allele was significantly associated with SC risk (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.85–0.96, P = 0.002), but not with AD risk (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.89–1.05, P = 0.401). Similarly, we also found that the rs722864A allele was associated with SC risk (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.86–0.97, P = 0.004), but not with AD risk (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.87–1.02, P = 0.139) as well. In subgroup analysis by smoking status, there was a significant decrease in lung cancer risk for the rs3769201T allele among ever smokers (OR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.85–0.94, P = 1.79E-05), but not among never smokers (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.84–1.13, P = 0.725) (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1A). We also found that the rs722864A allele was associated with lung cancer risk among ever smokers (OR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.85–0.94, P = 5.58E-05), but not among never smokers (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.80–1.12, P = 0.520) (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1B). However, heterogeneity test showed that the effect difference between ever smokers and never smokers was statistically non-significant for both SNPs (Phet = 0.349 for rs3769201 and Phet = 0.467 for rs722864). There is also no significant difference between AD and SC by heterogeneity test (Phet = 0.223 for rs3769201 and Phet = 0.524 for rs722864).

Table 3.

Associations between two tagSNPs and lung cancer risk stratified by smoking status in eight lung cancer GWASs

| Study | Case | Control | rs3769201 C > T | rs722864 G > A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Ever smokers | ||||||

| IARC | 2367 | 2508 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | 0.005 | 0.88 (0.79, 0.98) | 0.017 |

| Toronto | 236 | 272 | 1.04 (0.75, 1.43) | 0.820 | 1.05 (0.75, 1.48) | 0.770 |

| GLC | 433 | 258 | 0.97 (0.72, 1.31) | 0.844 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.32) | 0.835 |

| Harvard | 892 | 809 | 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) | 0.733 | ||

| MDACC | 1150 | 1134 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.218 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.05) | 0.179 |

| ATBC | 1732 | 1270 | 0.88 (0.77, 1.00) | 0.048 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.04) | 0.143 |

| CPSII | 600 | 383 | 0.79 (0.62, 1.00) | 0.051 | 0.86 (0.68, 1.10) | 0.241 |

| EAGLE | 1767 | 1339 | 0.90 (0.80, 1.02) | 0.107 | 0.90 (0.79, 1.02) | 0.104 |

| PLCO | 1243 | 1344 | 0.90 (0.77, 1.03) | 0.133 | 0.86 (0.74, 1.00) | 0.045 |

| Overall | 10420 | 9317 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.94) | 1.79E-05 | 0.89 (0.85, 0.94) | 5.58E-05 |

| Never smokers | ||||||

| IARC | 159 | 1253 | 0.94 (0.70, 1.25) | 0.663 | 0.95 (0.70, 1.31) | 0.769 |

| Toronto | 95 | 217 | 0.95 (0.61, 1.50) | 0.832 | 0.89 (0.55, 1.44) | 0.642 |

| GLC | 35 | 220 | 1.15 (0.61, 2.18) | 0.663 | 1.16 (0.59, 2.29) | 0.675 |

| Harvard | 92 | 161 | 1.03 (0.66, 1.60) | 0.896 | ||

| CPSII | 86 | 275 | 1.03 (0.67, 1.60) | 0.880 | 1.09 (0.70, 1.70) | 0.710 |

| EAGLE | 138 | 634 | 1.07 (0.77, 1.50) | 0.675 | 1.00 (0.70, 1.43) | 0.987 |

| PLCO | 126 | 470 | 0.76 (0.49, 1.17) | 0.208 | 0.72 (0.46, 1.12) | 0.145 |

| Overall | 731 | 3230 | 0.97 (0.84, 1.13) | 0.725 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.12) | 0.520 |

GWAS: genome-wide association study; AD, adenocarcinoma; SC, squamous cell carcinoma; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; NCI GWAS includes four sub-studies: the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study (ATBC), the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort (CPS-II), the Environment and Genetics in Lung Cancer Etiology (EAGLE), and the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovary Screening Trial (PLCO).

Discussion

In the present study, we used eight published GWASs from the TRICL-ILCCO consortium to investigate the associations between genetic variants in P38MAPK pathway genes and lung cancer risk. We found that two novel, potentially functional SNPs, i.e., rs3769201T and rs722864A alleles of ZAK, were both associated with a decreased lung cancer risk and a decreased mRNA expression level of ZAK. We also demonstrated that the rs3769201T and rs722864A alleles were significantly associated with risk of both lung AD and SC among ever smokers.

The P38 signaling cascade activation is triggered by several MAP3Ks. ZAK (sterile alpha motif and leucine zipper-containing kinase AZK) is a subfamily of MAP3Ks. ZAK takes part in cell cycle, apoptosis, neoplastic cell transformation, and several other cancer-related pathways [33],[34]. ZAK has two major different transcript variants, ZAK-α and ZAK-β. In the present study, we found that ZAK mRNA expression levels were significantly decreased in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues in 109 paired target tissue samples from TCGA. These findings suggest that ZAK may be a suppressor gene, since ZAK has been shown to behave as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting lung cancer growth [35]. However, more evidence supports that ZAK may have a pro-oncogenic function. For example, the TCGA data showed significantly higher ZAK mRNA expression levels in lung cancer tissues than adjacent tissues in cancers of the bladder, breasts, and stomach. Others showed that the overexpression of ZAK-α activated several cancer-related signaling genes, such as AP1 and NF-kB [36], and that ZAK also took part in cell proliferation in gastric cell lines [37] as well as enhanced human colon cancer HCT116 cell EGF-dependent motility and migration [38]. These studies were consistent with the results of the present study in which the two SNPs had a loss of function, as evident by the association with a decreased lung cancer risk due to a decreased mRNA expression level of the gene.

We also performed subgroup analysis by histology and smoking status, and we demonstrated that both rs3769201T and rs722864A alleles were associated with risk of SC and ever smokers, but not with AD and never smokers. Cigarette smoke is the major risk factor for lung cancer, especially for SC. It has been reported that the transcription factor (TF) STAT can be activated after tobacco smoke exposure [39]. Functional prediction analysis from HaploReg showed that rs3769201 had a STAT binding site motif, and the results of eQTL in the present study also demonstrated that the SNP may change the mRNA expression of ZAK. However, there is no significant difference between ever smokers and never smokers as tested by the heterogeneity test.

The present study has some limitations. First of all, although we found five pathways from the Molecular Signatures Database, perhaps some newly discovered genes may not have been included yet. Second, some published studies support that ZAK is an oncogene [37], but others have shown that ZAK may have the function of suppressing cancer growth [35]. More biological and molecular experiments should be performed to reveal the mechanisms underlying the observed associations. Finally, the analyses have not been adjusted to account for potentially important baseline risk covariates including family history.

In conclusion, the present study of eight published GWASs revealed two novel, potentially functional susceptibility loci in ZAK associated with lung cancer risk in European populations. Further validations and functional evaluations of these genetic variants are warranted to verify our findings.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- AD

Adenocarcinoma

- CI

confidence interval

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait loci

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- ILCCO

International Lung Cancer Consortium

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- OR

odds ratio

- SC

squamous cell carcinoma

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TRICL

Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung.

References:

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016. 66(1): p. 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith C, Genomics: SNPs and human disease. Nature, 2005. 435(7044): p. 993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, et al. , Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies multiple lung cancer susceptibility loci in never-smoking Asian women. Hum Mol Genet, 2016. 25(3): p. 620–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang X, et al. , Polymorphisms of the centrosomal gene (FGFR1OP) and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 14,463 cases and 44,188 controls. Carcinogenesis, 2016. 37(3): p. 280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, et al. , Genetic variant in DNA repair gene GTF2H4 is associated with lung cancer risk: a large-scale analysis of six published GWAS datasets in the TRICL consortium. Carcinogenesis, 2016. 37(9): p. 888–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan H, et al. , A Novel Genetic Variant in Long Non-coding RNA Gene NEXN-AS1 is Associated with Risk of Lung Cancer. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F, et al. , Susceptibility loci of CNOT6 in the general mRNA degradation pathway and lung cancer risk-A re-analysis of eight GWASs. Mol Carcinog, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazzalin CA, et al. , p38/RK is essential for stress-induced nuclear responses: JNK/SAPKs and c-Jun/ATF-2 phosphorylation are insufficient. Curr Biol, 1996. 6(8): p. 1028–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitmarsh AJ, et al. , Role of p38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases in the activation of ternary complex factors. Mol Cell Biol, 1997. 17(5): p. 2360–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janknecht R and Hunter T, Convergence of MAP kinase pathways on the ternary complex factor Sap-1a. Embo Journal, 1997. 16(7): p. 1620–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao M, et al. , Regulation of the MEF2 family of transcription factors by p38. Mol Cell Biol, 1999. 19(1): p. 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira RC, Delany AM, and Canalis E, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (DDIT3) induces osteoblastic cell differentiation. Endocrinology, 2004. 145(4): p. 1952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez del Arco P, et al. , A role for the p38 MAP kinase pathway in the nuclear shuttling of NFATp. J Biol Chem, 2000. 275(18): p. 13872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todd DE, et al. , ERK1/2 and p38 cooperate to induce a p21CIP1-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest. Oncogene, 2004. 23(19): p. 3284–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faust D, et al. , p38alpha MAPK is required for contact inhibition. Oncogene, 2005. 24(53): p. 7941–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon C, Goepfert H, and Boyd D, Inhibition of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by SB 203580 blocks PMA-induced Mr 92,000 type IV collagenase secretion and in vitro invasion. Cancer Res, 1998. 58(6): p. 1135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houle F and Huot J, Dysregulation of the endothelial cellular response to oxidative stress in cancer. Mol Carcinog, 2006. 45(6): p. 362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostaid MS, et al. , Lung cancer risk in relation to TP53 codon 47 and codon 72 polymorphism in Bangladeshi population. Tumour Biol, 2014. 35(10): p. 10309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, et al. , TP53 genetic polymorphisms, interactions with lifestyle factors and lung cancer risk: a case control study in a Chinese population. BMC Cancer, 2013. 13: p. 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhowmik A, et al. , ATM rs189037 (G > A) polymorphism and risk of lung cancer and head and neck cancer: A meta-analysis. Meta Gene, 2015. 6: p. 42–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su L, et al. , Genotypes and haplotypes of matrix metalloproteinase 1, 3 and 12 genes and the risk of lung cancer. Carcinogenesis, 2006. 27(5): p. 1024–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorgeirsson TE, et al. , A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature, 2008. 452(7187): p. 638–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howie BN, Donnelly P, and Marchini J, A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet, 2009. 5(6): p. e1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan YH, et al. , CBL is frequently altered in lung cancers: its relationship to mutations in MET and EGFR tyrosine kinases. PLoS One, 2010. 5(1): p. e8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberzon A, et al. , The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst, 2015. 1(6): p. 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu ZL and Taylor JA, SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Research, 2009. 37: p. W600–W605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle AP, et al. , Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res, 2012. 22(9): p. 1790–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward LD and Kellis M, HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res, 2012. 40(Database issue): p. D930–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lappalainen T, et al. , Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature, 2013. 501(7468): p. 506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruim RJ, et al. , LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics, 2010. 26(18): p. 2336–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pruim RJ, et al. , LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics, 2010. 26(18): p. 2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landi MT, et al. , A Genome-wide Association Study of Lung Cancer Identifies a Region of Chromosome 5p15 Associated with Risk for Adenocarcinoma. American Journal of Human Genetics, 2009. 85(5): p. 679–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tosti E, et al. , The stress kinase MRK contributes to regulation of DNA damage checkpoints through a p38 gamma-independent pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2004. 279(46): p. 47652–47660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho YY, et al. , A novel role for mixed-lineage kinase-like mitogen-activated protein triple kinase alpha in neoplastic cell transformation and tumor development. Cancer Res, 2004. 64(11): p. 3855–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang JJ, et al. , ZAK inhibits human lung cancer cell growth via ERK and JNK activation in an AP-1-dependent manner. Cancer Sci, 2010. 101(6): p. 1374–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu TC, et al. , Cloning and expression of ZAK, a mixed lineage kinase-like protein containing a leucine-zipper and a sterile-alpha motif. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2000. 274(3): p. 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. , Integrated exome and transcriptome sequencing reveals ZAK isoform usage in gastric cancer. Nat Commun, 2014. 5: p. 3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rey C, et al. , The MAP3K ZAK, a novel modulator of ERK-dependent migration, is upregulated in colorectal cancer. Oncogene, 2016. 35(24): p. 3190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niimori-Kita K, et al. , Identification of nuclear phosphoproteins as novel tobacco markers in mouse lung tissue following short-term exposure to tobacco smoke. FEBS Open Bio, 2014. 4: p. 746–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.