Abstract

Objective

The New York City’s Thrive (ThriveNYC) and the Los Angeles County Health Neighborhood Initiative (HNI) are two local policies focused on addressing the social determinants of behavioral health as a preventive strategy for improving health service delivery. On January 29, 2016, leaders from both initiatives came together with a range of federal agencies in health care, public health, and policy research at the RAND Corporation in Arlington, Virginia. The goal of this advisory meeting was to share lessons learned, consider research and evaluation strategies, and create a dialogue between stakeholders and federal funders – all with the purpose to build momentum for policy innovation in behavioral health equity.

Methods

This article analyzes ethnographic notes taken during the meeting and in-depth interviews of 14 meeting participants through Kingdon’s multiple streams theory of policy change.

Results

Results demonstrated that stakeholders shared a vision for behavioral health policy innovation focused on community engagement and social determinants of health. In addition, Kingdon’s model highlighted that the problem, policy and politics streams needed to form a window of opportunity for policy change were coupled, enabling the possibility for behavioral health policy innovation.

Conclusions

The advisory meeting suggested that local policy makers, academics, and community members, together with federal agents, are working to implement behavioral health policy innovation.

Keywords: Behavioral Health Policy, Community Engagement, Social Determinants of Health

Introduction

Across the country, locally driven policy initiatives are exploring novel strategies to achieve equity in behavioral health services and outcomes. For example, the city of Philadelphia has incorporated trauma-informed approaches into a range of city services, and promotes recovery, resilience, and self-determination through its Healthy Minds Philly initiative.1 Similarly, other systems are experimenting with incentives to implement collaborative care models or are adopting behavioral health homes to improve wrap-around services for vulnerable populations.2 In Los Angeles, the Community Partners in Care (CPIC) study used community partnering and engagement to implement depression quality improvement strategies in minority and under- resourced communities.3

New York City’s Thrive (ThriveNYC) and the Los Angeles County Health Neighborhood Initiative (HNI) looked to the CPIC experience for key lessons for behavioral health improvement. In both cities, policymakers envisioned engaging communities in improving services for behavioral health clients while addressing other social factors such as homelessness, safety/trauma, and physical activity. Both initiatives focus on addressing the social determinants of behavioral health as a preventive strategy and aim at ameliorating health service delivery by introducing place- based and cross-sector services.4-7

On January 29, 2016, leaders involved in HNI and ThriveNYC invited representatives of a range of federal agencies in health care, public health, and social policy research to convene at the RAND Corporation in Arlington, Virginia. The goal of this meeting was four-fold: 1) to review the implementation strategies of ThriveNYC and HNI to highlight shared strategies for addressing social determinants of behavioral health; 2) to share experiences and lessons learned to advance the implementation of these new policies; 3) to consider research and evaluation strategies for ThriveNYC and HNI in order to track its successes and improve chances of replicability in other localities; and 4) to create dialogue between federal funders and advocates of community-based behavioral health interventions to identify funding opportunities and build momentum for innovations aimed at behavioral health equity.

This article analyzes data obtained from meeting participants using John Kingdon’s multiple streams model of policy change8,9 to document stakeholders’ views and strategies for advancing behavioral health innovation.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

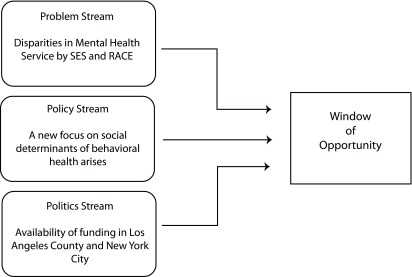

According to Kingdon, the implementation of a policy innovation happens once a window of opportunity for policy change becomes available. For a window of opportunity to form, three streams must be present: a problem stream, a policy stream and a politics stream.8-13

First, the problem stream refers to the moment when a policy issue requires attention. For example, persistent disparities in behavioral health outcomes motivated many policymakers to reflect on a social determinant-focused behavioral health approach.11,12,14 Increased attention to disparities in behavioral health service delivery in recent decades15 has had little effect on disparities associated with socioeconomic status (SES), gender, and race/ethnicity.16-22 While this association has long been known, expansion of behavioral health parity legislation21 has increased discussions of population health approaches to behavioral health such as prevention/early intervention and attention to social factors.23-25 These developments may have increased attention to the available data on behavioral health disparities and underlying social determinants.

Second, the policy stream refers to the moment a solution to the problem is available. For example, successful New York City initiatives to curb smoking, lower rates of teen pregnancy, and reduce childhood lead exposure exemplify population-based approaches that signal to policy leaders the feasibility of analogous behavioral health approaches.26 Similarly, the new focus on community-led service delivery and social determinants of health can be analyzed as part of the policy stream of behavioral health.27

Third, the politics stream refers to situations when both motivation and resources to solve a problem are available. Funding opportunities for behavioral health became available in both cities. Funding for the Los Angeles County HNI was provided by the Innovations Portfolio within the California Mental Health Services Act, a ballot initiative approved in 2006 to expand behavioral health services in the state. The goals of HNI were: 1) to increase service coordination among diverse health and behavioral health agencies; and 2) to develop community capacity to address local priorities for social determinants of behavioral health. In New York City, Mayor Bill DeBlasio and First Lady Chirlane McCray were key to the advancement of ThriveNYC, a $850 million investment in 54 targeted initiatives over four years that would move behavioral health care in a more holistic direction.28 Analogous to HNI, ThriveNYC focuses on increasing service coordination among multi-sector city agencies, community-based organizations, health care systems, and academic researchers to implement a mental health-in-all-policies approach. Figure 1 shows how the three streams come together to create a window of opportunity.

Figure 1. Kingdon’s process streams8.

The importance of this model is that it underscores that once a problem is recognized and a solution articulated, it is only when the political climate makes the time right for change and no other constraints opposes the action that a new policy can be implemented. This conceptualization of policy change is especially pertinent given that despite longstanding evidence of the importance of social factors to health,8 the goal of integrating health and social services has not yet been widely implemented,9 particularly in the United States and especially in behavioral health.10,12 Therefore, given the coupling of these three streams, the advisory meeting that took place on January 29, 2016 can be analyzed as an example of a “window of opportunity”8,9,13 through which behavioral health policy innovation is being negotiated to enable widespread implementation.

Advisory Meeting

The advisory meeting that serves as the source of data for this article took place at the RAND Corporation in Arlington, Virginia on January 29, 2016. A total of 40 individuals attended, including representatives from: six Institutes within the National Institutes of Health; six federal health policy and services agencies (eg, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Office of the Surgeon General); two private or other federal research funding organizations; two regional health departments; a payer organization; and three academic institutions.

The advisory meeting began with a presentation by community and consumer stakeholders who described their own and family members’ experiences seeking services. They highlighted the need for service innovation and addressed the importance of behavioral health equity. Next followed a brief review of effective approaches to close gaps in systems of care. For example, presenters identified the disparities in quality of care and outcomes in behavioral health for racial and ethnic minority and under-resourced communities. Then, teams from public health agencies in New York City and Los Angeles County described the objectives of ThriveNYC and HNI and the strategies used for their implementation. The afternoon was dedicated to obtaining feedback from agency representatives in attendance. In general, attendees encouraged the evaluation of innovative models, gave suggestions for building synergies, and endorsed the goal of addressing disparities to achieve behavioral health equity. At the closing of the meeting, research partners presented different evaluation strategies to stimulate uptake of effective approaches by other communities.

Data Sources

Data sources were: 1) ethnographic field notes taken during the meeting and 2) semi-structural interviews conducted after the meeting. Both data sources were triangulated to refine and validate findings.

Field Notes

During the advisory meeting extensive field notes were taken. Field notes are shorthand reconstruction of events and conversations that took place in the field and are finalized after the fact. These data represent one of many levels of textualization of an event.29,30

Semi-Structured Interviews

Between February and March 2016, the research team invited all the attendees at the advisory meeting to participate in reflective follow-up interviews. Fourteen of the 40 attendees (35%) responded and agreed to be interviewed (Table 1). Interviews were conducted over the phone, lasted approximately half an hour, and were audio recorded and transcribed.

Table 1. Sectors represented by participants of the January 29, 2016 meeting held in Arlington, Virginia.

| Stakeholder Type | n attending January 29 meeting | n interviewed |

| Community | 4 | 2 |

| Academic researcher | 5 | 4 |

| Federal service policy maker | 7 | 2 |

| Local health agency leader | 11 | 4 |

| Research policy maker/funder | 13 | 2 |

| Total | 40 | 14 |

Participation was voluntary and confidential. The interview protocol was developed in collaboration with community and policy partners. The purpose of the interviews was to learn about attendees’ perceptions of issues that can support policy innovation raised during the advisory meeting. Using an eight-question interview protocol, the informants were asked about the strategies to implement HNI and ThriveNYC, the most relevant approaches to address social determinants of health, and the priorities for ensuring progress in integrating social factors into health policy and services (Appendix A). Prior to analysis, transcripts were sent back to the informants for edits and final approval. The RAND Corporation’s Human Subjects Protection Committee approved all study procedures.

Data Analysis

Data were entered in Dedoose version 7.5.22, a qualitative data analysis software program that allows for marking and aggregating segments of text pertaining to specific categories of information. Two researchers conducted data analysis and developed codes to mark each informants’ perspective on policy progress (eg, policy aim and rationale and the steps needed to achieve it). Both researchers coded a fourth of the data individually, then came together to compare codes and develop a codebook. Once the codebook was finalized, half of all data were re-coded. The researchers then conducted reliability tests using the Dedoose testing function until they achieved a reliability coefficient of .78. Between rounds of reliability testing, the coders reconciled any disagreements and refined the codebook. The final codebook was used to code all remaining data. Once the coding was complete, the codes were combined to define themes that described groupings of codes. Finally, text corresponding to the codes and themes were compared against the data in the field notes taken during the meeting. Analysts identified the field note content that complemented and augmented the coding results.

Results

In presenting results, we attribute remarks made during the meeting to “attendees” and attribute remarks from an interview to “informants.” Attendees of the advisory meeting described a policy window of opportunity characterized by a shared understanding of the challenge of behavioral health disparities, a shared vision for innovation, and distinct but complementary strategies for policy implementation.

Overall, the attendees recognized the problem stream, such as the persistence of disparities in behavioral health outcomes and ongoing challenges accessing behavioral health care. They also shared an understanding of the policy stream and indicated that a community approach with a social determinant focus was a viable solution to the existent disparities in behavioral health service delivery. Finally, within the politics stream, the attendees talked with state representatives about strategies to secure funding toward behavioral health innovation. Notably, this window of opportunity highlights that behavioral health research has a strong responsibility to public health policy not only by shaping the problem stream (ie, characterizing disparities) but also by defining the policy (ie, solution to these disparities) and the politics streams (ie, ability to secure funding).

Persistence of Disparities in Behavioral Health: The Problem Stream

According to attendees who came together to discuss persistence in behavioral disparities across communities, HNI and ThriveNYC illustrate the emergence of new models for locally driven behavioral health policy innovation centered on addressing community needs and prioritizing social determinants of health. It is notable that novel elements of these initiatives emerged alongside their more traditional goals like improving the coordination and quality of behavioral health care and services. For example, an academic partner explained, “The attempt to look at social determinants of behavioral health issues is what’s probably newer and novel … different than some of the models done in rural areas.” Similarly, the attendees shared difficulties of implementing change across agencies, “There is so much potential here and it’s a little bit of a messy landscape right now, but we’ve lived in that world for a long time but you know some of it is just being prepared to strike when the opportunity arises […].” Thus, the problem stream was clearly shared by the attendees and was a motivating force behind their dialogue. For example, an agency leader stated, “It may be worth the investment in educating or even getting non-health sector organizations involved. […] They understand that a lot of their work is important and very much plays into physical, as well as mental, health maintenance. And it may be simple to start there – that’s part of that social norm of an organization or change.”

A Shared Vision for Policy Change: The Policy Stream

The attendees shared a similar vision of policy innovation and the ways in which HNI and ThriveNYC implement such a vision. This vision encompassed two important changes. First, that policy innovation would address social determinants of behavioral health as a structural context in which behavioral health difficulties develop or persist. Second, that policy innovation would address the social determinants in ongoing partnership with communities – rather than in service to them.

All the attendees expressed agreement that social determinants of behavioral health were a key policy target. As a federal agency leader noted during the meeting, “Social determinants is [sic] one of those things that seems to be on everybody’s mind.”

HNI and ThriveNYC were described as innovative reforms that reflected attendees’ available and commonsensical vision that behavioral health could be improved by addressing social determinants of health. For instance, one academic attendee said that many existing public health programs focused on social factors that impacted physical health. While an informant described the extension to behavioral health as therefore sensible: “There were plenty of programs that worked on improving hypertension, diabetes, things like that, but I think the attempt to look at social determinants of behavioral health issues is what’s probably newer and novel...”

Beyond a shared vision that focused on the social determinants of health to improve behavioral health, many of the informants cited the urgency of working with the community to address social needs. They saw the HNI and ThriveNYC initiatives as opportunities to actualize an approach in which community voices could have an impact. For example, during the meeting, an attendee explained that having the community lead the implementation of new policy in a “bottom-up” manner could prove a particularly effective strategy. Similarly, an academic informant explained that HNI and ThriveNYC are innovative because, instead of having the “usual attempt to improve community health” from a “top-down” approach, the policies “improve health from the community’s perspective.” In an interview, a federal funder summarized the vision for HNI and ThriveNYC as policy innovations that included attention to social factors and community partnership. For him, these policies represent a “new era for public health” that implements programs that are “flexible and more multi-sectoral” through an understanding of “the community and what their needs are.”

Overall, the informants shared a similar vision about behavioral health policy innovations that would combine a social determinant approach with “bottom-up” community partnership model. All attendees anticipated inclusion of social determinants in behavioral health policy and the inclusion of new community stakeholders in order to break down silos and effectively attend to the health of local communities. During the meeting, system and academic partners for LAC and NYC remarked on the similarities of this vision with other national efforts, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Framework and community-based efforts in Philadelphia like Healthy Minds Philly.

Strategies for Policy Implementation: Politics Stream

While informants described a shared vision for behavioral health policy innovation, they differed in their descriptions of the next steps necessary to make the vision a sustainable reality. Despite their differences, attendees were concerned with similar issues such as the replicability of innovative models, the need for research to track the impact of these initiatives, and the sustainability of ambitious initiatives and the ways in which these aligned with the higher-level politics of their communities, counties and cities.

Many attendees expressed the importance of conducting evaluations that document the impact of innovative approaches. For example, at the meeting, an agency leader argued for the importance of conducting formative evaluations so that progress could be mapped in real time, allowing interventions to self-correct and improve iteratively during implementation. Other stakeholders highlighted the need for rigorous controlled evidence to track the impact of the strategies that have been implemented thus far. During an interview, a research policymaker said, “I thought that the main important outcome of the meeting was to get the evaluation started.” This policymaker felt it would be important to “start to show there is a model, what it is you want to replicate, and that there is an effect and that this is important,” indicating that defining and demonstrating impact of a specific approach was a key step. These types of discrete results, the policymaker continued, “is what drives people. Otherwise they think, well it’s just some interesting idea, but is it really suitable for me, or is it even going to work?”

Similarly, a federal agency leader informant noted that, “one of the key major challenges is how do you measure impact and what type of metrics would you use that seem to be both reasonable and that everybody would agree.” This agency leader expressed concern that, when considering social determinants of health, “there are so many factors you have to deal with and it may not be that easy to … demonstrate impact.” Other informants argued for the importance of conducting evaluations to focus the most effective strategies to the areas of highest need. As a research funder explained in an interview, “data and metrics and analytics [are] an essential ingredient” to understand which approaches to address social determinants would narrow the health equity gap.

Finally, attendees discussed the need for sustainable funding for innovative program. During the meeting, administrative stakeholders, in particular, described seeing programs come and go. They identified the importance of secure funding to support successful implementation of HNI and ThriveNYC. A federal agency leader explained that in both New York City and Los Angeles County “each of the programs needed to adjust to the political and financing realities of their particular situation,” and tailor expectations for community participation. Another informant also remarked on the way that funding can profoundly shape the nature and scope of the innovation. In an interview, one research funder used the metaphor of a water pipe to explain that while it has been clear for some time that structural factors matter, securing resources to address them was novel: “You have to address the pipe and not just the poisoning, right? Not just the lead poisoning. You’re going to have to go there but often times the funding is only around to address the poisoning symptoms.” In fact, during the meeting, agency leaders expressed their frustration with not knowing what funding is “coming down the pipeline,” and sought ways to anticipate strategies to secure sustainability considering future uncertainties.

Discussion

Research on policy innovation underscores that policy development is a holistic process where different elements of the local culture become key aspects of the policy system.31 Kingdon’s8,9 model of policy innovation argues that a unique “window of opportunity” opens when three streams are coupled: problems, policies and politics.

This model has been applied to analyze policy change around behavioral health inequalities and social determinants of health.32,33 Using Kingdon’s model of a window of opportunity to analyze this advisory meeting provides insights into the negotiations resulting in policy innovation. Overall, in accord with Kingdon’s model,8,9 the attendees saw an opportunity for the problem, policy, and politics to coalesce for transformation in behavioral health services of their cities.

Many of the concerns described in relation to the politics stream had to do with sustainment of the momentum for behavioral health policy transformation. Specifically, attendees cited the need for replicability and transferability, quick evaluation results, and secure funding as key aspects of ensuring forward progress. Attendees’ emphases on these contributors to sustainability seem to reflect their awareness of how quickly a window of opportunity can close. Unless funding, evaluation data, and an ability to show demonstrable impact were available, they implied, the politics stream seemed vulnerable to shifting priorities. While we lack space in this article to describe the activities of HNI or ThriveNYC since the advisory meeting, recent political threats to Medicaid indicate that attendees’ concerns about elements of sustainability were valid.

The advisory meeting, as an example of a window of opportunity, illustrates three characteristics of the policy process. First, policy decisions rarely take place at a single point in time but rather over months or even years. The various viewpoints about next steps expressed in the advisory meeting provide a detailed example of the iterative and cyclical dialogue needed to innovate around policy. Policy innovation can accommodate varied “fronts” of activity because policy decisions often reflect broad directions that are being negotiated by various stakeholders continuously. Second, policymaking rarely occurs in public but rather often behind ‘closed doors.’ This advisory meeting is an important opportunity for discussion, strategy refinement, and partnership building.

Third, policy making entails many non-decisions. The lack of observable action or outcome may signify a complex set of forces that have stifled a decision or prevented proposals from being enacted.11,34 Evaluating these behind-the-scenes spaces renders the policy implementing process more transparent and efficient and highlights the political process of policy change. In particular, a window of opportunity allows leveraging similar but not identical efforts, pulling together local efforts that may be interested in using similar strategies (ie, attention to social determinants of health and community engagement) to address shared problems (ie, behavioral health care disparities).

Conclusion

This study highlights that key behavioral health policy stakeholders share a vision of behavioral health policy change that combines attention to social determinants of health with community engagement. Kingdon’s8,9 model shows that this shared vision is a marker of a policy window that can lead to policy change. As Kingdon’s8,9 model suggests, a policy change comes to fruition in the rare instance that the three streams create a window of opportunity and there are no oppositions to action. The advisory meeting suggested that local policymakers, academics, and community members together with federal agents are working to implement behavioral health policy innovation. Whatever lessons accrue from the HNI and ThriveNYC implementation, other public policy stakeholders can contribute to opening this window of opportunity by considering the potential implications for their localities and supporting the success of these two local initiatives.

Appendix A

Attendees, Jan 29, 2016 Arlington, VA Interview Protocol

1. What made you interested in attending the meeting at RAND in Arlington, VA on January 29th?

a. Prompt: That is, what seemed particularly compelling to you about the activities around social determinants of mental health taking place in NYC and LAC?

2. In your understanding, what are the key priorities of the HNI and ThriveNYC initiatives?

a. Prompt: What are some of the key similarities and differences between the LAC and NYC initiatives?

3. In your view what would be the most promising strategies for addressing social determinants of mental health?

a. Alternate (if this raises COI concerns): Or, tell us a few of your thoughts about where you hope these initiatives lead …

b. …or what you imagine could be their impact.

4. Other than New York and Los Angeles, to what extent have you seen other approaches to addressing social determinants of mental health across the country?

a. Prompt: Or, what other policy initiatives might you identify as similarly focused on address social determinants of mental health?

b. Prompt: What do you see as key challenges to implementing these kinds of initiatives?

c. Prompt if relevant (eg, for funders or policy makers): Given that your mandate is to improve mental health how would you address social determinants so that it falls within the scope of your agency?

5. What are you doing differently or thinking about differently as a result of the meeting?

a. Follow-up: If nothing has changed for you, why do you think that’s the case?

6. For you, what was a key take-away from the meeting?

a. Prompt: That is, what was a key lesson you learned as a result of hearing more about these initiatives?

7. What do you think would be key next steps for the group that came together at that meeting?

a. Prompt: What kinds of activities – eg, establishing workgroups, continuing communication -- would help us maintain momentum?

8. Is there anything else that you would like to talk about? What questions do you have for us?

References

- 1.Philadelphia: Behavioral Health Leads Trauma-Informed Community Change. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Last accessed November 15, 2016 from https://blog.samhsa.gov/2016/06/20/philadelphia-behavioral-health-leads-trauma-informed-community-change/#.WW61j9NuJmB June 20, 2016.

- 2. Druss BG, Esenwein von SA, Glick GE, et al. Randomized trial of an integrated behavioral health home: The Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(3):246- 255. https://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi. ajp.2016.16050507 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. . Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1268-1278. 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones L, Chung B, Dixon E, et al. Community Partners in Care (CPIC): Community Engagement and Planning Framework. Los Angeles, California: Workbook; 2015. Last accessed May 2, 2018 from http://www.communitypartnersincare.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CEP-Manual_FINAL-Version.pdf

- 5. Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K; Community Partners in Care Steering Council . Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning community partners in care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780-795. 10.1353/hpu.0.0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chung B, Ong M, Ettner SL, et al. . 12-month outcomes of community engagement versus technical assistance to implement depression collaborative care: a partnered, cluster, randomized, comparative effectiveness trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10)(suppl):S23-S34. 10.7326/M13-3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, Krause LK. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD009905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed New York: Longman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sabatier P, Weible C. Theories of the Policy Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilkinson RG, Marmot M. Social Determinants of Health: the Solid Facts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Exworthy M. Policy to tackle the social determinants of health: using conceptual models to understand the policy process. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):318-327. 10.1093/heapol/czn022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heinz A, Charlet K, Rapp MA. Public mental health: a call to action. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):49-50. 10.1002/wps.20182 10.1002/wps.20182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shim R, Koplan C, Langheim FJ, Manseau MW, Powers RA, Compton MT. The social determinants of mental health: an overview and call to action. Psychiatr Ann. 2014;44(1):22-26. 10.3928/00485713-20140108-04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Nation Free of Disparities in Health and Health Care. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGuire TG, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):393-403. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyer PA, Penman-Aguilar A, Campbell VA, Graffunder C, O’Connor AE, Yoon PW; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Conclusion and future directions: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report - United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(3):184-186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyer PA, Yoon PW, Kaufmann RB; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Introduction: CDC health disparities and inequalities report. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(3):3-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2013 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD; May 2014.

- 20. Institute of Medicine Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Institute of Medicine Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22. USDHHS Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity, a Supplement to Mental Health, a Report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service. 2002:Vol 2. [PubMed]

- 23. Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity--mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973-975. 10.1056/NEJMp1108649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cordell KD, Snowden LR. Embracing comprehensive mental health and social services programs to serve children under California’s Mental Health Services Act. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2017;44(2):233-242. 10.1007/s10488-016-0717-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris NB. How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime. TED Talks Last accessed November 15, 2016 from http://www.ted.com/talks/nadine_burke_harris_how_childhood_trauma_affects_health_across_a_lifetime/transcript?language=en.

- 26. de Blasio BM, McCray I, Buery R Jr, Bassett MT. ThriveNYC: A Roadmap for Mental Health for All. Last accessed May 3, 2018 from https://thrivenyc.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ThriveNYC.pdf

- 27. Pham HH, Cohen M, Conway PH. The Pioneer accountable care organization model: improving quality and lowering costs. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1635-1636. 10.1001/jama.2014.13109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wahlbeck K, Cresswell-Smith J, Haaramo P, Parkkonen J. Interventions to mitigate the effects of poverty and inequality on mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(5):505-514. 10.1007/s00127-017-1370-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maanen Jv. Tales of the Field. On Writing Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolfinger NH. On writing fieldnotes: collection strategies and background expectancies. Qual Res. 2002;2(1):85-93. 10.1177/1468794102002001640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Exworthy M, Berney L, Powell M. ‘How great expectations in Westminster may be dashed locally’: the local implementation of national policy on health inequalities. Policy Polit. 2002;30(1):79-96. 10.1332/0305573022501584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ståhl T, Wismar M, Ollila E, Lahtinen E, Leppo K. Health in all policies. Prospects and potentials. Helsinki: Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lukes S. Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan; 1974. 10.1007/978-1-349-02248-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Doloreux D, Shearmur R, Filion P. Learning and innovation: implications for regional policy. An introduction. Can J Reg Sci. 2001;24(1):5-12. [Google Scholar]