Abstract

Objective

To determine how to improve the cultural appropriateness and acceptability of an extant evidence-based model of family intervention (FI), a form of ‘talking treatment,’ for use with African Caribbean service users diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families.

Design

Community partnered participatory research (CPPR) using four focus groups comprising 31 key stakeholders.

Setting

Community locations and National Health Service (NHS) mental health care settings in northwest England, UK.

Participants

African Caribbean service users (n=10), family members, caregivers and advocates (n=14) and health care professionals (n=7).

Results

According to participants, components of the extant model of FI were valid but required additional items (such as racism and discrimination and different models of mental health and illness) to improve cultural appropriateness. Additionally, emphasis was placed on developing a new ethos of delivery, which participants called ‘shared learning.’ This approach explicitly acknowledges that power imbalances are likely to be magnified where delivery of interventions involves White therapists and Black clients. In this context, therapists’ cultural competence was regarded as fundamental for successful therapeutic engagement and outcomes.

Conclusions

Despite being labelled ‘hard-to-reach’ by mainstream mental health services and under-represented in research, our experience suggests that, given the opportunity, members of the African Caribbean community were highly motivated to engage in all aspects of research. Participating in research related to schizophrenia, a highly stigmatized condition, suggests CPPR approaches might prove fruitful in developing interventions to address other health conditions that disproportionately affect members of this community.

Keywords: Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR), Health Disparities, Ethnicity, Schizophrenia, Psychosis, Minority Mental Health, African Caribbean

Introduction

This article describes engagement between African Caribbean service users diagnosed with schizophrenia, their families, health care professionals and members of the wider community to inform cultural adaptation of an extant evidence-based psychosocial intervention for the management of schizophrenia. In our study, African Caribbean refers to people of African ancestry with family origins in the Caribbean, including those who self-identify as Black British, mixed heritage or Black Caribbean.

African Caribbean people in the United Kingdom are more likely than any other ethnic group to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and related psychoses.1,2 As reported by the multi-site Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses (AESOP) study, the relative risk of African Caribbeans receiving a narrowly defined schizophrenia(F20)3 diagnosis is nine-fold that of White British people [IRR 9.1 (6.6-12.6)].4 Disparities in rates of diagnosis extend into care and treatment. At every level of service, African Caribbean’s access, experiences, and outcomes of psychiatric care are inferior to that of both the White majority population and other minorities.5-8

African Caribbeans’ negative experiences of psychiatric care have generated fear and mistrust of statutory mental health services delivered by the National Health Service (NHS), adversely affecting help-seeking.9 Evidence of multiple help-seeking attempts3 counters the prevailing narrative of Caribbeans’ unwillingness to engage with psychiatric services, resulting in this community being labelled ‘hard-to-reach’ by mental health services.9 Findings from the AESOP study suggest that structural and organizational service barriers10 coupled with previously reported community-level stigma11 are implicated in delayed access to care and long duration of untreated psychosis.

Untreated mental illness imposes considerable burden on caregivers and is associated with family breakdown, social isolation and greater likelihood of service user relapse and re-hospitalization.12 Among African Caribbeans, delayed access to care is also associated with increased family tension and conflict and more adverse care pathways, including greater likelihood of police involvement.8 In their review of schizophrenia care in the United Kingdom, these issues led the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)13 to conclude that the care of African Caribbeans was in crisis. In consequence, they recommended development of culturally appropriate, evidence-based psychological therapies to meet the needs of this population.

NICE guidance13 states that all service users diagnosed with psychosis who are in regular contact with their families should be offered Family Intervention (FI), a psychosocial treatment with a strong evidence-base of cost and clinical effectiveness.14,15 Family Intervention takes a holistic approach to care and treatment, paying particular attention to establishing therapeutic alliance and goal attainment. Core components of the various approaches include psycho-education, problem solving, and stress management.14 Reported service user benefits include improved medication compliance, self-care and problem-solving, which correlate with reduced risk of psychotic relapse.14 For families, FI has been found to reduce perceived burden of care and to improve caregiver ill-health.16

In community mental health engagement events involving both authors, service users and their families stated that more culturally appropriate ‘talking treatments’ and strategies to improve knowledge about schizophrenia and psychosis were needed. FI offers the potential to meet both these objectives. However, there is currently no evidence that the reported benefits of FI are generalizable to African Caribbean people14 or that standard FI approaches would be acceptable to service users and their families. We therefore sought to determine whether members of the African Caribbean community would be willing to partner with health care professionals and academics to co-produce a culturally appropriate and acceptable version of an extant evidence-based, cognitive behavioral model of FI.17

Involving African Caribbean Communities in Schizophrenia Research

In recent years, patient and public involvement (PPI) has been increasingly encouraged, especially in publicly funded research in the United Kingdom. For example, underscoring its commitment to PPI in research, the government-funded National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) established INVOLVE (http://www.invo.org.uk/) to sponsor PPI in health and social care research. INVOLVE describes meaningful PPI as that which produces research with or by members of the public vs for or about them.18

Given the historical legacy of mistrust of mental health services and paucity of research from African Caribbean community perspectives, we undertook to go beyond merely involving or engaging community members in creating solutions to the well-documented issue of lack of access to psychological care.13 Instead, we sought to establish an authentic community-academic partnership19 by adopting a community partnered participatory research (CPPR) approach developed by the US-based non-governmental organization Healthy African American Families (HAAF) in collaboration with Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science and the Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.19

CPPR extends community-based participation research (CBPR) models, emphasizing the guiding principle of equality between community and academic partners in identifying problems, devising, implementing, and evaluating solutions and disseminating findings. CPPR also adopts an explicitly strengths- (vs deficits) based model and identifies, harnesses, and builds community assets and capacity.20 According to Jones and Wells,19 key characteristics of a CPPR project include: 1) involving community members and academics as equal partners in all phases of research and decision-making; 2) sharing leadership and resources equitably; 3) simultaneously valuing the relevance of experience and critical importance of evidence; and 4) two-way capacity building aimed at developing research that benefits the community.

CaFI: A Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) Approach

Our CPPR-based process began in 2010 with the first in a series of community-based Faith and Mental Health in Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Communities conferences. The purpose of the conference was to enable community members to identify problems associated with inferior schizophrenia care experienced by African Caribbeans from their perspectives and to work as equal partners with academics and health providers to develop culturally relevant solutions. More than 500 delegates (including African Caribbean community members, clinicians, policy makers and academics) participated in the weekend-long conference. An open invitation to collaborate in developing a research proposal to address mental health disparities in the African Caribbean community was given. Around 100 conference delegates responded, attending a subsequent meeting to explore the issues in greater depth. These conversations and conference evaluation echoed previous reports9 of African Caribbeans’ deep dissatisfaction with mainstream mental health provision. Despite policy initiatives to deliver race equality in mental health,6,21 participants regarded services as culturally insensitive at best and frequently institutionally racist. Community members identified key research priorities as: 1) addressing the lack of psychological therapies; and 2) developing accurate, accessible information about mental illness in general and schizophrenia in particular.

A former service user and co-author of this paper was among those who volunteered to join the grant writing team to produce research to address these priorities. Our study to test the feasibility of co-producing, implementing and evaluating culturally adapted FI (CaFI)22 with African Caribbean service users diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families was funded by NIHR (HS&DR Ref: 12/5001/62). Subsequently, community volunteers became members of CaFI’s Research Advisory Group, shaping all aspects of the study, and Research Management Group, providing research governance and oversight of the study.

The CaFI research protocol and a commentary on Phase 1 of the study has been published elsewhere.22 Specifically, this report identified how key stakeholders’ views about what constitutes culturally appropriate and acceptable FI informed co-production of a psychosocial intervention specifically designed to meet the needs of African Caribbean service users and their families. Details of the cultural adaptation process, including stakeholders’ involvement in developing a therapy manual to support delivery of the intervention, will be provided in a forthcoming publication.

Methods

This qualitative study used focus group interviews with key stakeholders. The study received ethical approval from the UK’s Health Research Authority (REC Reference: 13/NW/0571).

Recruitment

We used community radio, local newspapers and advertising via places of worship, libraries, and other community settings to engage with and recruit a volunteer sample of participants. Advertising and recruitment materials were developed with CaFI’s African Caribbean Research Advisory Group (RAG) members to ensure images and text were culturally sensitive and accessible. We also developed a study website (http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/ReACH/aboutus).

Conscious that researchers may be regarded as agents of power and surveillance,20 we actively sought to enhance trust-building by reducing the distance between community members, health care professionals and academics – for example, holding meetings in easily-accessible community venues such as faith-based organizations (FBOs) and reimbursing community members for their time and incidental expenses.

Inclusion Criteria

Recruitment targeted current and former adult service users (aged ≥18 years) who self-identified as being of African Caribbean origin and/or were in receipt of support from voluntary sector agencies such as African Caribbean Mental Health Services (ACMHS). Service users’ diagnoses were verified by their case workers.

Caregivers (including paid support workers, family and friends), advocates (such as ACMHS), community members, and health care professionals working within the National Health Service (NHS) and/or social care systems with experience of working with African Caribbean people were also recruited using volunteer sampling. Unlike service users, caregivers, advocates and health care professionals could be from any ethnic/cultural background. They were not screened for mental illness.

Exclusion Criteria

Non-English speakers from all groups were excluded as we did not have resources for translation. This was deemed acceptable by the RMG as the majority of people of African Caribbean origin in the United Kingdom either migrated from the English-speaking Caribbean or were born in the United Kingdom. Potential service user participants were excluded if they lacked capacity to provide informed consent as determined by their clinical teams.

Participants

Thirty-one volunteers took part in three separate stakeholder focus groups. Focus Group 1 comprised 10 service users with ICD-10 F20-F2923 or DSM-V24 schizophrenia diagnoses. Focus Group 2 (n=14) involved family members (spouses or partners, siblings and parents (mostly mothers) and advocates (such as ACMHS). Seven health care professionals (including social workers, occupational therapists [OTs] and registered mental health nurses [RMNs]) participated in Focus Group 3.

To achieve maximum variation, a sampling frame was developed to create a fourth mixed focus group (n=11) from the three stakeholder groups. Participants were purposefully selected using key criteria such as age, sex, professional background. The purpose of this group was to summarize and verify findings from the previous groups, address any discrepancies and agree the information that formed the basis of the expert consensus conference (Phase 2 of the study), in which the contents of the therapy and manual to support delivery were agreed (paper forthcoming).

Data Collection

Considered less susceptible to researcher bias than individual, one-to-one researcher-led interviews, focus groups are often used in emancipatory research as participants’ views and group dynamics ultimately shape the data.25 Each focus group commenced by establishing ground rules to create ‘safe spaces’ in which all individuals’ voices could be heard.

Video presentations (pptx) were used to outline the purpose and process of the session and present the main components of existing FI model to participants, namely: 1) service user assessment; 2) family assessment; 3) psycho-education; 4) stress-management and coping; and 5) problem solving and goal planning.

During the first three focus groups, participants were asked to comment on: a) the face validity of the different components of the extant FI; and b) what, if anything, needed to be done to improve the cultural appropriateness for African Caribbeans. Although the core content remained constant, separate interview schedules were developed for each group to facilitate data collection from different stakeholder perspectives. For example, whereas service users and caregivers were asked about their experiences of being recipients of mental health services, health care professionals’ views and experiences of providing care for African Caribbeans (including perceptions of similarities and difference with other groups) were sought. The fourth focus group differed in that participants were presented with the findings from the first three groups and asked (through ranking, voting and discussion) to determine which of the suggested adaptations would improve the model’s cultural appropriateness and acceptability from the perspective of African Caribbeans. All focus groups were facilitated by the study’s principal investigator (PI), supported by the senior research assistant (RA).

Data Analysis

Data were digitally recorded, transcribed, checked for accuracy, fully anonymous, and analyzed using Framework Analysis26 by the PI and RA with input from the wider team and qualitative methods experts independent of the study team. Framework Analysis was particularly well-suited to our study as it allows for exploration of a priori topics, for example, views about FI content as well as emergent themes such as participants’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to implementation. Strategies to ensure methodological rigor27,28 included reliability checks of coding (80% agreement), peer review (by qualitative methods expert external to the research team) and participant verification of findings and conclusions (by the fourth focus group and presenting findings to a wider group). NVivo Version 1029 was used to support data management and analysis.

Results

As exemplified by these quotes, all participants agreed that a culturally appropriate ‘talking treatment’ for African Caribbeans was desirable:

“I’ve been in and out of hospital since 1988 and in all that time I’ve never had anybody come with talking therapy or cognitive therapy. So it’s not a thing that I have discussed in the past but I realise that most of the therapy is being given by middle class White Europeans who don’t really know the Black agenda … it’s like there’s a gap there.” (African Caribbean Male Service User, Focus Group 1)

“I think it’s great! It would definitely help that the family understand the problem and communication is better.” (White British Female Therapist, Focus Group 3)

Asked to comment on the extant FI model,17 participants agreed that it had good face validity. No components were regarded as irrelevant or inappropriate. However, they indicated that a number of additional items were required to improve its cultural appropriateness for African Caribbean service users and their families. Although space does not allow us to provide full details here (available in forthcoming publication), we share two examples to illustrate how exploring participants’ views about each FI component contributed to the process of culturally adapting FI to produce CaFI.

In relation to the ‘Service User Assessment’ component of the extant model, participants endorsed the validity of it sub-components, namely: symptoms/experiences (such as hearing voices others cannot hear); factors that improve or worsen symptoms; and treatment of schizophrenia (including alternatives to mainstream approaches to managing symptoms). However, they suggested that additional topics such as experiences of racism and discrimination and alternative conceptualizations of mental health and illness (including beliefs about the role of spirituality) would create a more culturally specific intervention:

“You [therapist] also have to be aware of the belief system within a family, because you might meet up with the spiritual aspect …which you’re probably not familiar with, and I think you need to be aware of that and not be judgmental.” (African Caribbean male advocate, Focus Group 3)

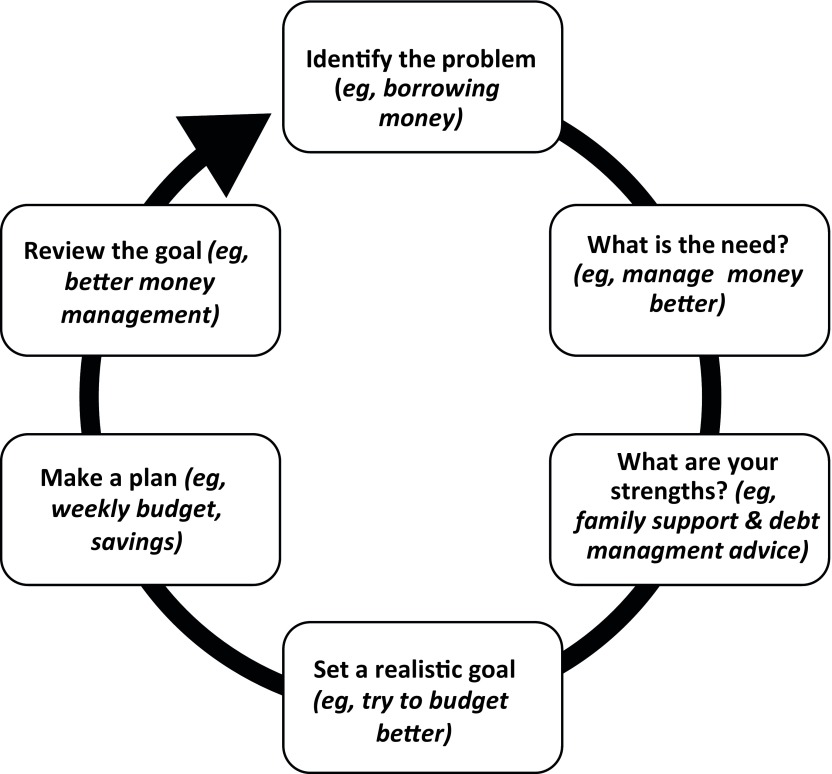

To ascertain participants’ views on the problem-solving and goal setting component of FI, the steps that the service user, family, and therapist work through to solve problems and achieve agreed goals were presented to focus group members using a visual representation created by the CaFI team (Figure 1) to explain the process.

Figure 1. Working example of problem solving and goal planning.

Respondents found this approach helpful, endorsing its application of the assets-based principles that underpin CPPR. In particular, they liked the solutions-oriented approach, which focuses on success rather than failure and breaking down goals into small, achievable steps. In this context, they suggested that this process be made more explicit and that opportunities to celebrate even small successes should be created throughout as illustrated by this quote:

“I think also if it [the process] does break down at any point, I think it would be useful to focus on how far you’ve travelled and the positive rather than the negative. It might have broken down and then I think the natural thing is to say ‘it’s not worked, it’s negative’. But actually, you’ve got so far round that circle and that’s a very positive step and, if you focus on that, then maybe next time you’ll get past that place and on to the next stage.” (African Caribbean female caregiver, Focus Group 2)

Participants further suggested that this approach could help family members to view service users in a new, more positive light. Rather than seeing them as the problem, highlighting individuals’ resources and desire to find solutions could enable families to work more collaboratively thus fostering conflict resolution and confidence building:

“I think what this [Problem-solving component] does is … gets the family to realize, and also the service user, how resourceful they are to find a solution to their problem and then it’s on paper so they know ‘oh right, what was going on in my head now is on paper.’ So in one way it develops confidence that ‘I have got the resources’.” [Group agreement]” (Asian male advocate & carer, Focus Group 2)

To make this aspect of the intervention more culturally relevant and underscoring the assets-based approach, participants also suggested highlighting Caribbean-specific resources such as using informal, community based rotating savings and credit

association (ROSCA) popular with migrant communities who were often excluded from mainstream banks due to low credit rating. Known as ‘pardner’ in Caribbean communities, members brought the system to the United Kingdom in the 1950s and 60s, enabling them to save – particularly for large value items such as property and or to fund the costs of bringing their children to the United Kingdom. While acknowledging the risk of joining financially unregulated schemes based entirely on mutual trust, participants believed that with appropriate support, they have the potential to reconnect marginalized service users with their communities.

Additionally, participants felt that the visual representation presented to them (Figure 1) highlighted the need for more culturally appropriate tools to support delivery of the intervention more generally. Focus group members suggested greater use of storytelling, pictures and other non-literary formats to maximize inclusion. Further, they also cautioned against over-reliance on Internet-based resources based on assumptions that ‘everyone is online’ vs prosaic but potentially more accessible formats:

“So you talked earlier about sending out the assessment prior to [the session] so they can have a look at that… Can it be sent out in a DVD form for those who are not that comfortable with reading so they can watch it on the TV? Can it be done in audio form so that if they’ve got a disability?” (African Caribbean male advocate, Focus Group 2)

Despite ambivalence about whether it was achievable in practice, participants were unanimous that what would distinguish CaFI as truly African Caribbean was not only its content but its ethos of delivery. In particular, they advocated an explicitly collaborative,

three-way ‘shared learning’ approach between service users, family members and therapists. ‘Shared learning,’ a phrase coined by members of the mixed focus group, places as much emphasis on therapists’ acquisition of culturally relevant knowledge as service users and families learning about psychosis. An integral aspect of this approach is therapists’ acquiring cultural awareness and skills to facilitate mutuality. For example, by learning about African Caribbean cultures alongside identifying and sharing their backgrounds:

“‘I’ve got something to learn from you, but you’ve also got something to learn from me’ … it’s like flattening it out [the] power, because they’ve got a massive amount of power that is mostly misused…” (African Caribbean female advocate, Focus Group 2)

As indicated by this quote, African Caribbeans are acutely aware of the power imbalance often inherent in therapeutic relationships. Openly acknowledging that power issues can be magnified when White therapists work with Black service users and developing strategies to address this was crucial for trust-building. Participants stated that therapists needed to acquire the skills to facilitate and engage in discussions about race-based discrimination, including institutional racism. Among African Caribbean participants, these experiences often formed part of their models of mental illness but were frequently not acknowledged:

“There’s massive talk of institutionalized racism in so many different areas, whether that’s education, crime and other areas. We know it can’t be separate from the health area as well so there has to be an acknowledgement that it’s there.” (African Caribbean male advocate, Focus Group 2)

Being open, transparent and willing to deal with uncomfortable truths relating to service users and families’ experiences and different culturally based models of mental illness was regarded as essential for reducing social distance, flattening hierarchies and fostering engagement between therapists and members of African Caribbean communities:

“I think it’s really important for people to feel like they have power in this situation, that they have some level of control, because I think quite often, particularly in mental health services, people feel very powerless, and we talk about our ‘person- centered approach’ and ‘partnership’ and I see quite often that that isn’t reality … So I think, in this instance of family therapy [CaFI], if somebody comes in and feels like ‘actually my voice is really going to be heard and I can actually affect some change for myself’ then that would maybe lead to it being more productive.” (Mixed ethnicity female health care professional, Focus Group 4)

Discussion and Conclusion

The UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) advocates for meaningful involvement to produce research with versus for patients and members of the public. In response to a call from the National Institute for Health and Excellence (NICE)13 for novel interventions to address the crisis in schizophrenia care for African Caribbeans, we partnered with service users, their families, community members, and health care professionals to: 1) determine whether a culturally adapted version of FI was desirable; 2) identify modifications of an extant evidence-based model17 and co-produce a more culturally appropriate version thereof. Given historically adversarial relationships between African Caribbeans and mental health services,7,9,21 using CPPR principles to achieve meaningful engagement with members of this so-called hard-to-reach community was an important achievement.

Applying CPPR principles19 meant, for example, that African Caribbean service users, their families, and members of the wider community were actively involved in every stage of the research process – from identifying research priorities, through developing the research questions and writing the grant application and dissemination of findings. Shared leadership and equality of stakeholders in the partnership is evidenced in the role of service users and caregivers as co-applicants and collaborators and, with community volunteers, as members and chairs of Research Management Group (RMG) and Research Advisory Group (RAG).

In keeping with CPPR, the process of gathering data to inform cultural adaptation of FI was underpinned by methodological rigor (reliability checks and verification processes) while explicitly valuing different ways of knowing as demonstrated by ensuring that the views of all stakeholders, whether experts by experience (service users and caregivers) or profession (health care professionals and advocates) received equal weighting. Two-way capacity building was integral to this assets-based approach. Academics were embedded within the community and community members became part of the research team. For example, those who wished to do so received honorary university contracts, enabling access to academic resources, and research methods training to facilitate capacity building and development of future research to benefit the community.

Partnering to undertake research to underpin co-production of more culturally appropriate and acceptable FI, endorses under-served communities’ perspective that, although frequently labelled ‘hard-to-reach’, they are instead ‘seldom heard.’30 Our study indicates that, given the opportunity, members of this community were highly motivated to engage in problem-solving research that fosters hope.20,31 African Caribbeans’ involvement in developing a culturally appropriate talking treatment for a highly stigmatizing condition could have implications beyond mental health. For example, it suggests the possibility of partnering with African Caribbeans to develop research to address physical health conditions that disproportionately affect African Caribbeans, such as diabetes, hypertension and some cancers.

Acknowledgments

The CaFI study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Health Service and Delivery Research Programme (HS&DR) (12/5001/62). This article presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health. The study sponsor is The University of Manchester and the host NHS Trust Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (formerly Manchester Mental Health & Social Care Trust).

References

- 1. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Schizophrenia: The NICE Guidelines on Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care (updated edition). National Clinical Guideline Number 82. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nazroo J, King M. Psychosis - symptoms and estimated rates. In: Sproston K, Nazroo J, eds. Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates (EMPIRIC). London: The Stationery Office; 2002:47. [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fearon P, Kirkbride JB, Morgan C, et al. ; AESOP Study Group . Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in ethnic minority groups: results from the MRC AESOP Study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(11):1541-1550. 10.1017/S0033291706008774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, Priebe S, Mole F, Feder G. Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182(2):105-116. 10.1192/bjp.182.2.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CQC/DH National Mental Health and Learning Disability Ethnicity Census: Count Me In 2010. London: Care Quality Commission (CQC) & National Mental Health Development Unit (NMHDU) at Department of Health; 2010. Last accessed May 21, 2018 from http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/count_me_in_2010_final_tagged.pdf.

- 7. Morgan C, Kirkbride J, Mallett R, et al. Social isolation, ethnicity, and psychosis: findings from the AESOP first onset psychosis study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(2):232. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, Leff J. Negative pathways to psychiatric care and ethnicity: the bridge between social science and psychiatry. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(4):739-752. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00233-8 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00233-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keating F, Robertson D, McCulloch A, Francis E. Breaking the circles of fear: A review of the relationship between mental health services and African and Caribbean communities. London: The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, et al. ; AESOP Study Group . Pathways to care and ethnicity. 2: source of referral and help-seeking. Report from the AESOP study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(04):290-296. 10.1192/bjp.186.4.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mantovani N, Pizzolati M, Edge D. Exploring the relationship between stigma and help-seeking for mental illness in African-descended faith communities in the UK. Health Expect. 2017;20(3):373-384. 10.1111/hex.12464 10.1111/hex.12464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Sampogna G, et al. The role of relatives in pathways to care of patients with a first episode of psychosis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(7):631-637. 10.1177/0020764014568129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and Management. NICE Clinical Guidelines. London: Department of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W. Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Issue 12. Nottingham, England: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002;32(5):763-782. 10.1017/S0033291702005895 10.1017/S0033291702005895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lobban F, Postlethwaite A, Glentworth D, et al. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions reporting outcomes for relatives of people with psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(3):372-382. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barrowclough C, Tarrier N. Families of Schizophrenic Patients: Cognitive Behavioural Interventions. London: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayes H, Buckland S, Tarpey M. INVOLVE: Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. NIHR; 2012. Last accessed May 21, 2018 from http://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/INVOLVEBriefingNotesApr2012.pdf

- 19. Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407-410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320-321. 10.1001/jama.2009.1033 10.1001/jama.2009.1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Department of Health Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Care: an action plan for reform inside and outside services and the Government’s response to the Independent inquiry into the death of David Bennett. London: Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edge D, Degnan A, Cotterill S, et al. Culturally-adapted Family Intervention (CaFI) for African-Caribbeans diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families: a feasibility study protocol of implementation and acceptability. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2(1):39. 10.1186/s40814-016-0070-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organisation The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24. APA Diagnostic and Stastical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied health research. London: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gibbs G. Analyzing qualitative data. Los Angeles: Sage; 2007. 10.4135/9781849208574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gibson W, Brown A. Working with qualitative data. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009. 10.4135/9780857029041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NVivo 8 [software program, v10]. Burlington, Mass.: QSR International Pty Ltd 2007.

- 30. Redwood S, Gale NK, Greenfield S. ‘You give us rangoli, we give you talk’: using an art-based activity to elicit data from a seldom heard group. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):7. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K; Community Partners in Care Steering Council . Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning community partners in care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780-795. 10.1353/hpu.0.0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]