Abstract

Objectives

Schools can play an important role in addressing the effects of traumatic stress on students by providing prevention, early intervention, and intensive treatment for children exposed to trauma. This article aims to describe key domains for implementing trauma-informed practices in schools.

Design

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) has identified trauma-informed domains and principles for use across systems of care. This article applies these domains to schools and presents a model for a Trauma-Informed School System that highlights broad macro level factors, school-wide components, and tiered supports. Community partners from one school district apply this framework through case vignettes.

Results

Case 1 describes the macro level components of this framework and the leveraging of school policies and financing to sustain trauma-informed practices in a public health model. Case 2 illustrates a school founded on trauma-informed principles and practices, and its promotion of a safe school environment through restorative practices. Case 3 discusses the role of school leadership in engaging and empowering families, communities, and school staff to address neighborhood and school violence.

Conclusions

This article concludes with recommendations for dissemination of trauma-informed practices across schools at all stages of readiness. We identify three main areas for facilitating the use of this framework: 1) assessment of school staff knowledge and awareness of trauma; 2) assessment of school and/or district’s current implementation of trauma-informed principles and practices; 3) development and use of technology-assisted tools for broad dissemination of practices, data and evaluation, and workforce training of clinical and non-clinical staff.

Keywords: School-based Services, Traumatic Stress Disorder, Community Participation, Mental Health Services, Community

Background

Nationally, 61% of youth in 2013-2014 reported being exposed to some form of violence or abuse in the past year,1 with ethnic minorities at increased risk compared with majority populations due to such issues as being disproportionately affected by poverty, discrimination, and other social determinants of health such as educational disparities.2,3 A survey of more than 28,000 6th grade students, in a large urban school district serving primarily Latino students living in poverty, found that 94% of youth had exposure to trauma in the prior year, and 40% reported direct victimization involving a gun or knife.4 Despite being at increased risk for traumatic stress, ethnic minority youth are less likely to receive support services such as mental health care when it is needed,5 thus schools can play an important role in providing that care.6,7

In addition to negative mental health sequelae, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and behavior problems, exposure to violence is associated with lower grade-point average, decreased high school graduation rates,8 decreased IQ, as well as significant deficits in attention, abstract reasoning, long-term memory for verbal information, and reading ability.9,10 Researchers have found that cumulative adverse childhood events, including violence exposure, is also associated with greater suspensions and absenteesism,4 and greater chronic health conditions in childhood and lower employment productivity in adulthood.11

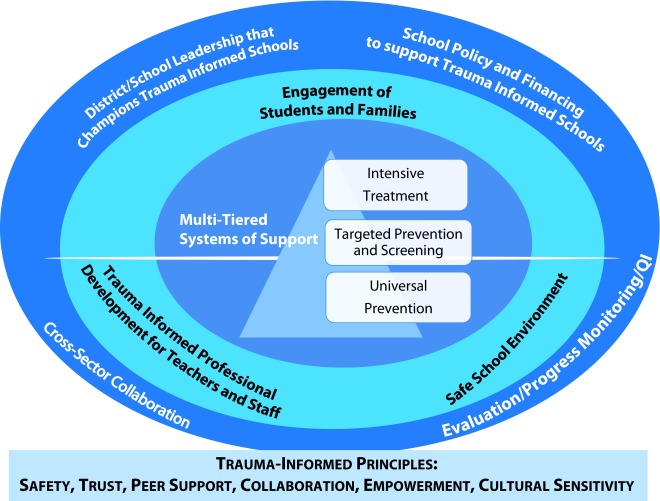

With this growing body of research documenting the lifelong deleterious effects of traumatic stress on development, there has been a national call to action for trauma-informed child-serving systems of care.12,13 According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), trauma-informed systems integrate practices that incorporate the following elements: safety; trust; peer support; collaboration; empowerment; and culture.14 In 2015, Chafouleas and colleagues integrated SAMHSA’s trauma-informed elements with a service delivery approach to school supports that span universal prevention to interventions.15 In this article, we provide case illustrations of Trauma-Informed School Systems (Figure 1), that draw on the trauma-sensitive system outlined by SAMHSA and the service delivery model of Chafouleus and colleagues.

Figure 1. Trauma-informed school system.

This figure is adapted from SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

In Figure 1, we illustrate a Trauma-Informed School System Framework and highlight the key components that span the whole school and district. Frequently detection and treatment of trauma-related mental health problems in students is the focus of trauma-informed services in schools. Although important, intervening with school organizational and broader community and policy factors in preventing and responding to traumatic stress can create a trauma-informed school environment where practices on campus are approached with a trauma “lens,” ie, a perspective that understands how violence and trauma can disrupt the social and emotional and cognitive growth of students.

The outer circle in Figure 1 contains the macro level aspects of a trauma-informed school. School implementation research has found that school leadership and policies, procedures, and financing can be important to sustain trauma-informed practices.16 National policy recommendations have also emphasized implementing evidence-based interventions across a continuum of services with evaluation, progress monitoring, and quality improvement of services, focusing on outcomes relevant to education stakeholders.17 Schools can be seen as a public health model “hub,” playing a critical role of prevention and early intervention for students who have experienced traumatic stress, and anchoring cross-sector collaboration with other child-serving agencies such as justice, child welfare, specialty mental health, and primary care.12

The next inner circle in Figure 1 depicts trauma-informed practices within a school that influence a positive school climate, such as a safe school environment and strong school engagement with students and families. Positive school climate is associated with less bullying and harassment on campus, as well as improved school achievement, attendance, and better student mental health.18 Often, teachers have not received training in responding to students who have experienced adversities or traumatic events, and feel poorly equipped to support students who have experienced trauma.19 Thus, another key component of Trauma-Informed School Systems is the provision of short- and long-term training and professional development for all school staff to increase staff awareness and knowledge about how trauma can affect students’ social, emotional, behavioral, and academic functioning. Furthermore, similar to experiences of first responders and child welfare workers, teachers have also been found to develop posttraumatic stress symptoms as a result of being exposed to students’ accounts of stress and trauma, also known as secondary traumatic stress.20 An important part of teacher training is learning about the importance of monitoring teachers’ levels of stress, and implementing coping strategies and self-care.21 Finally, the innermost circle of Figure 1 represents the trauma-informed social-emotional supports for students on a campus, organized in a multi-tiered system of supports from universal prevention (Tier 1), to targeted prevention and screening (Tier 2), to treatment (Tier 3).22

Currently, most schools address only a fraction of the components included in this comprehensive model. However, with enhanced awareness, support, and resources, schools will be better positioned to broaden their trauma-informed policies and programming.

In the following section, we present three case examples from our school community-research partnerships with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), which illustrate successes and challenges in implementing some of the Trauma-Informed School System components outlined in Figure 1. Case 1 illustrates the outer circle of this framework, describing a pilot developed at the district level to improve prevention, early detection, and treatment of traumatic stress in schools. Although trauma-informed efforts are not yet universally practiced throughout the district, we present how two schools have incorporated some of these concepts despite multiple barriers. Designed from the outset as a trauma-informed school, Case 2 demonstrates how the Trauma-Informed Principles can be applied in a school context for ethnic minority youth. Case 3 illustrates how a local elementary school has implemented components of the framework’s inner circle especially for improving trauma awareness with families and school staff and the broader community.

Case 1. A District Pilot to Monitor a Trauma-Informed School System Approach

LAUSD is a large urban school district serving 664,774 students in grades K-12, with 80% of students living in poverty and 21% of students classified as English language learners. Almost 75% of students are Latino, mainly of Mexican descent, and 8% are African American. Although the District has a School Mental Health unit (SMH) comprising more than 350 professionals, mostly psychiatric social workers (PSWs), this workforce falls far short of meeting the high level of student and family needs across the more than 900 K-12 schools. For example, national recommendations for the school social worker:student ratio is 1:250, but in LAUSD that ratio is estimated to be 1:1900, with PSWs working across 1-3 school sites.23

For more than 17 years, LAUSD SMH has partnered with academic clinician researchers to create and disseminate trauma-informed practices conducive to being delivered in schools efficiently and effectively, and developed in a pragmatic, culturally sensitive, and “school friendly” way for students, families, and school communities.24,25 At its foundation, this community-academic partnership incorporates trust, respect, transparency, and cultural values and history across research and community partners.26 One priority that the District has had was taking a public health approach to dissemination and evaluation.

From the outermost circle of the Trauma-Informed School System model, one key component of the continued growth of trauma-informed services in the District has been the sustained leadership of SMH that has prioritized the delivery of these practices. Recently this leadership has championed schools to begin offering a multitiered system of trauma-informed supports: Tier 1 universal prevention programs, such as the Resilience Classroom Curriculum;27 Tier 2 targeted group prevention interventions, such as the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS),28 and Tier 3 intensive treatments, such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT),29 among others. Unfortunately, not all schools have the resources to offer these programs, with schools often having competing demands for limited funds and workforce.

State and local policies have also provided opportunities to sustain and spread these practices. For example, the State of California’s Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) provides funding for the delivery of the evidence-based trauma practices above.30 LAUSD SMH leaders have advocated successfully for the reimbursement of trauma interventions, allowing them to potentially sustain the delivery of individual, group, and family trauma interventions. At the local level, District leadership has prioritized School Safety and Safe Learning Environments in the district’s Strategic Plan for 2016-2019, which includes a commitment to restorative justice practices, which focus on restoring connection and healing, improved school climate, and tiered systems of services.31 With these policies in place, schools may be more motivated to adopt trauma-informed practices. Financing of tiered services is through an array of local, state and federal funding. One challenge however is the lack of funding available for screening and early detection of traumatic stress and other mental health problems.

Recently, SMH and academic partners have co-created and piloted an online progress monitoring and cloud-based care management tool that allows SMH to track students across tiered services and screen students electronically. Social workers can track whole classrooms by measuring school climate and connectedness and resilience characteristics of students (from the Resilience Youth Development Module, California Healthy Kids Survey).32 After receiving a trauma-informed social-emotional learning curriculum in their classroom,27 students are offered the Wellness Check-Up, which screens them for risk of traumatic stress, depression, and substance abuse following parental written consent. The Wellness Check-Up can then be used to identify students who need a higher level of service. This online tool can track students’ evaluations and participation in services and allows district leaders and frontline school social workers to approach trauma service delivery from a public mental health perspective. As part of Tier 3, LAUSD schools also facilitate cross-sector collaboration with child welfare and probation, community agencies, and mental health facilities.

Case 2. Whole School Approach: Community Health Advocates School

In 2009, the Los Angeles Board of Education passed the Public School Choice Initiative, which created a mechanism for teachers, administrators and other school stakeholders to submit plans to develop newly constructed schools or to redesign long-term underperforming public schools. Aware of the impact that poverty and violence were having on their students, a group of teachers in South Los Angeles came together with a shared mission of creating a trauma-informed school, in collaboration with academic partners who had expertise in trauma. The community of South Los Angeles is racially and ethnically diverse with 68% Latino, 28% African American, and 2% White.33 Forty-four percent of youth in South LA were born outside of the United States34 and fewer than 50% of households speak English at home.33

From the outset, community empowerment and collaboration were central to the development process. Realizing the range of experience and expertise in their community, the teachers leading the development effort established a community-partnered approach that sought to give voice to families, gang intervention workers, priests, community health providers and local police. This process was guided by the principle of “Earned Insurgence,” which asserts that leaders must earn the right to fight alongside the community.35 A vision for the school began to take shape when one stakeholder commented, “Imagine a school training kids how to identify their own and others’ trauma and equipping them with tools to heal themselves and others.” The Community Health Advocates School (CHAS) was designed to empower future social workers and community health advocates of South Central LA. As one stakeholder remarked, it would be a school, “of the community, by the community, and for the community.” In 2012, CHAS opened its doors to 376 students with a staff of 15: 12 teachers; one counselor; one principal; and one office technician. Four years later the school has grown considerably; 516 students are currently enrolled and supported by a staff of 45 that includes: 29 teachers; one principal; two assistant principals; three counselors; and 10 other support staff.

Trauma-informed principles are woven into CHAS’s academic curriculum. The curriculum is grounded in the Linked Learning Model36 whereby career pathway concepts are integrated throughout the four-year curriculum. With CHAS’s emphasis on social work and advocacy, students are taught about individual, community, and cultural and societal factors that increase the likelihood of violence and traumatic events in their communities. At CHAS, instruction is not limited to the classroom. Students are empowered to translate their coursework into action in the community. For example, in 11th grade literature, students read “The Catcher in the Rye” and assess the protagonist’s behavioral and mental health needs. Upon completion of this assignment, students attend a National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) conference to advocate for individuals experiencing mental health difficulties. In 9th grade, students integrate classes in algebra and geometry for an assignment to redesign South Los Angeles into a safer and healthier community, with an emphasis on reducing violence in their neighborhood.

These academic efforts are grounded in a school-community that views its students and staff through a trauma lens. School-wide programming at CHAS aims to build a strong sense of community where students feel safe physically and emotionally, trust staff, and seek support from peers. Restorative practices are central to these efforts. With origins in indigenous communities, restorative justice is a form of mediation that aims to bring reconciliation between offender and victims.37 Every Friday begins with classroom-based community circles that promote connectedness among students. Harm and re-entry circles de-escalate conflicts and restore trust and safety after conflicts arise between students or between students and staff. Trained facilitators oversee the dialogue encouraging openness, transparency, and equality. Although the process may include restitution, it is primarily designed to heal relationships among people and within the community rather than to impose punishment. On several occasions, these circles have culminated in the realization that both the perpetrator and victim have been affected by traumatic events. As a result of these school-wide restorative efforts, CHAS has experienced two consecutive semesters with zero suspensions.

Case 3. Harmony Elementary School: Trauma-Informed School Leadership that Engages Families, Students, and Staff

The principal at the newly built Harmony Elementary School in a primarily immigrant Latino neighborhood, overwhelmed by gang-related violence and poverty, a lack of community infrastructure, and racial/ethnic disparities in academic outcomes, prioritized trauma-informed services and engagement to address the community’s needs, illustrating a number of the trauma-informed principles described in Figure 1 (eg, safety, trust, peer support, collaboration, empowerment). He supported trauma education to help educators recognize when students’ emotional and behavioral responses may be resulting from traumatic stress. Employing a community organizing approach, this principal trained teachers to have one-on-one conversations with parents about why they became educators and what they hoped to accomplish – practices that highlight development of trust and transparency between school staff and families. These critical conversations were made possible by bilingual staff (teachers and/or teaching assistants). He also trained staff to listen to the stories of students and parents and identify recurrent themes. Common concerns were used to bring neighborhood families together for peer support at house meetings (small group meetings in the neighborhood) to develop plans for social action and empowerment.

One frequent concern was neighborhood safety. In response, the principal planned neighborhood walks to inventory conditions, opinions, and resources in the area surrounding the school. The data gleaned from these efforts were used to approach city council members and police department leaders, who were invited to the school to listen to parents trained to tell “three-minute stories” about their concerns about violence in their community, a civics exercise of collaboration and mutuality. After several years, the school’s family engagement ratings improved on the district’s annual parent survey, and with improving school climate and sense of safety, Harmony was the first school in this community to reach California’s standardized test score benchmark, an indicator that Harmony Elementary was closing the gap in standardized test scores.

This family-school engagement has also translated into higher-than-usual levels of parent involvement in trauma interventions for students. A significant protective factor for resilience following a child’s trauma is the quality of parent-child interactions and communication; yet, a frequent challenge in delivering school-based programs is often engaging parents in low-resourced communities to participate in treatment. In preparing to deliver CBITS student groups, the school psychiatric social worker at Harmony met with parents after students screened at-risk for posttraumatic stress. Although the meeting’s purpose was to obtain treatment consent and invite parent participation in treatment, the meeting also became a critical part of parent education about trauma’s effects on children. Parents for the first time realized that their children were “silently suffering” with feelings of hopelessness and anxiety. The social worker empowered parents to play a key role in supporting their child’s recovery and resilience through improved communication at home.

Recommendations

There has been a growing national recognition that the effects of traumatic stress on children and their families need to be better identified and addressed by child-serving systems of care.12 The American Academy of Pediatrics has highlighted the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACES) on childhood health and wellbeing13 and the SAMHSA-supported National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has played a key role over the past 16 years in disseminating evidence-based trauma services for youth across the United States.38 This article applies general trauma-informed concepts to school systems and illustrates through case examples how a trauma-informed approach can be implemented in schools, from district-level change, to building a trauma-informed school from the ground up, to broad community-school engagement in addressing traumatic stress. As has been described in other studies, adoption of trauma-informed approaches in schools has varied by the needs of school communities, available school resources, and schools’ capacity to implement change. As a result, some have prioritized adopting targeted trauma prevention programs, others have taken a whole-school approach, and others have initiated work in schools through creation of trauma-informed school crisis teams and disaster response.6,28,39,40 Our case examples suggest that it is possible to implement a range of trauma-informed activities in schools, recognizing that variation across schools may exist in terms of priorities and capacity to adopt new practices.

Assessment of School Staff Knowledge and Awareness of Trauma

As part of the initial evaluation component in a Trauma-Informed School System, a first step for a school or district is to assess the staff’s level of readiness to adopt trauma-informed practices and to identify what is already occurring on a campus. Assessments now exist for many of these dimensions. The Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC) is designed to measure staff attitudes about trauma-informed services across a number of systems of care, including schools.41

Assessment of School and/or District’s Current Implementation of Trauma-Informed Principles and Practices

The SAMHSA-funded Treatment and Services Adaptation Center for Resilience, Hope, and Wellness in Schools (TSA for Schools; traumaawareschools.org) has developed an online trauma-informed school self-assessment that provides schools with a rubric to help gauge their use of trauma-informed programming and policies and provides concrete recommendations for building on and enhancing these efforts.42 Future research is needed to evaluate how these assessments relate to the ability of a district or school to redesign themselves into a trauma-informed system.

Development and Use of Technology-Assisted Tools for Broad Dissemination of Practices, Data and Evaluation, and Workforce Training of Clinical and Non-Clinical Staff

Technology can also facilitate school staff’s adoption of trauma-informed school principles and practices. Case 1 described the creation of online tools to measure school climate and screen and track student’s needs. Such online data collection can also help school leaders make more informed decisions regarding the needs of their students and the value of additional support services. Furthermore, training opportunities for clinicians practicing in schools can be limited due to scarce funding and lack of infrastructure and support.43 To enhance professional development efforts, online trauma intervention trainings and implementation support platforms such as the CBITS website (cbitsprogram.org) have been shown to be an efficient approach for enhancing training for school mental health clinicians44 and therefore may be a cost-efficient strategy for providing training and ongoing consultation to school-based clinicians.

Workforce training and implementation tools for teachers and other nonclinical school staff is another important aspect of professional development in disseminating trauma-informed practices in schools. Although some schools offer trauma-focused in-services, it is unclear if this approach alone is sufficient to successfully enhance knowledge and skills of non-clinicians.40 Online simulations to reinforce teachers’ skills in interacting with students with trauma histories, and web-based trainings for teachers exposed to the secondary traumatic stress following teaching highly stressed and traumatized students are being developed in partnership with teachers and administrators to address this potential gap.

Conclusion

In conclusion, implementation of the core components of a Trauma-Informed School System can build on the strengths of each school and district, with no “one-size-fits-all” approach. Schools often have existing resources and programs that can be incorporated into a trauma-informed system, with some sites choosing to expand one component of the framework, while others choose to adopt other components initially. Irrespective of the “starting point,” the implementation of trauma-informed school systems will benefit from ongoing community-research partnerships to develop feasible and scalable tools and to evaluate their effectiveness in helping schools and districts successfully achieve desired changes.14,15

References

- 1. Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(8):746-754. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basch CE. Aggression and violence and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81(10):619-625. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00636.x 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, de Groat CL. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. J Couns Psychol. 2010;57(3):264-273. 10.1037/a0020026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramirez M, Wu Y, Kataoka S, et al. . Youth violence across multiple dimensions: a study of violence, absenteeism, and suspensions among middle school children. J Pediatr. 2012;161(3):542-546.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548-1555. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaycox LH, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, et al. . Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: a field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(2):223-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kataoka S, Stein BD, Nadeem E, Wong M. Who gets care? Mental health service use following a school-based suicide prevention program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1341-1348. 10.1097/chi.0b013e31813761fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grogger J. Local violence and educational attainment. J Hum Resour. 1997;32(4):659-682. 10.2307/146425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beers SR, De Bellis MD. Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):483-486. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Ondersma SJ, et al. . Violence exposure, trauma, and IQ and/or reading deficits among urban children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(3):280-285. 10.1001/archpedi.156.3.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. . Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, et al. . Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008;39(4):396-404. 10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Academy of Pediatrics Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Lifelong Consequences of Trauma. Last accessed July 17, 2017 from https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf

- 14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chafouleas SM, Johnson AH, Overstreet S, Santos NM. Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Ment Health. 2016;8(1):144-162. 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Ment Health. 2010;2(3):105-113. 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. §1400, 2004.

- 18. apa A, Cohen J, Guffey S, Higgins- D’Alessandro A. A review of school climate research. Rev Educ Res. 2013;83(3):357-385. 10.3102/0034654313483907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baweja S, Santiago CD, Vona P, Pears G, Langley A, Kataoka S. Improving implementation of a school-based program for traumatized students: identifying factors that promote teacher support and collaboration. School Ment Health. 2016;8(1):120-131. 10.1007/s12310-015-9170-z 10.1007/s12310-015-9170-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Borntrager C, Caringi JC, van den Pol R, et al. . Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2012;5(1):38-50. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/1 754730X.2012.664862 [DOI]

- 21. Hydon S, Wong M, Langley AK, Stein BD, Kataoka SH. Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2015;24(2):319-333. 10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kilgus SP, Reinke WM, Jimerson SR. Understanding mental health intervention and assessment within a multi-tiered framework: contemporary science, practice, and policy. Sch Psychol Q. 2015;30(2):159-165. 10.1037/spq0000118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. School Social Work Association of America Last accessed July 17, 2017 from http://www.sswaa.org/.

- 24. Stein BD, Kataoka S, Jaycox LH, et al. . Theoretical basis and program design of a school-based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: a collaborative research partnership. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29(3):318-326. 10.1007/BF02287371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong M. Commentary: building partnerships between schools and academic partners to achieve a health-related research agenda. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1)(suppl 1):S149-S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407-410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Marlotte L, Garcia E, et al. . Adapting and Implementing a School-Based Resilience-Building Curriculum Among Low-Income Racial and Ethnic Minority Students. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2017;21(3):223-239. 10.1007/s40688-017-0134-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. . A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(5):603-611. 10.1001/jama.290.5.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393-402. 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) Evidence-Based Practices, Promising Practices, and Community-Defined Evidence Practices Resource Guide 2.0; 2011. Last accessed June 26, 2018 from http://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/dmh/159575_EBPPPCDEResourceGuide2_0.pdf

- 31. Los Angeles Unified School District LAUSD Strategic Plan; 2016-2019. Last accessed July 17, 2017 from http://achieve.lausd.net/Page/477.

- 32. Hanson TL, Kim J-O. Measuring Resilience and Youth Development: The Psychometric Properties of the Healthy Kids Survey. Issues & Answers. REL 2007-No. 34. San Francisco, CA: Regional Educational Laboratory West; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Los Angeles Department of Public Health Supplement to Community Health Assessment: Service Planning Area 6: South LA. 2014. Last accessed July 17, 2017 from http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/plan/docs/CHA_CHIP/SPA6Supplement.pdf

- 34.e California Endowment. South Los Angeles: Quick Facts. Last accessed July 17, 2017 from http://www.calendow.org/places/south-los-angeles.

- 35. Moses R. An earned insurgency: quality education as a constitutional right. Harv Educ Rev. 2009;79(2):370-381. 10.17763/haer.79.2.937m754251521231 10.17763/haer.79.2.937m754251521231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rogers-Chapman MF, Darling-Hammond L Preparing 21st century citizens: The role of work-based learning in linked learning. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. 2013. Last accessed June 26, 2018 from https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/preparing-21st-century-citizens-role-work-based-learning-linked-learning.pdf.

- 37. Umbreit M. Restorative justice through victim-offender mediation: A multi-site assessment. West Crim Rev. 1998;1(1):1-29. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pynoos RS, Fairbank JA, Steinberg AM, et al. . The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: collaborating to improve the standard of care. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008;39(4):389-395. 10.1037/a0012551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dorado JS, Martinez M, McArthur LE, Leibovitz T. Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): a whole-wchool, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive Schools. School Ment Health. 2016;8(1):163-176. 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vona P, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SK, Stein BD, Wong M. Supporting students following school crises: from the acute aftermath through recovery. In: Harrison JR, Schultz BK, Evans SW, eds. School Mental Health Services for Adolescents. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baker CN, Brown SM, Wilcox PD, Overstreet S, Arora P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the attitudes related to trauma-informed care (ARTIC) scale. School Ment Health. 2016;8(1):61-76. 10.1007/s12310-015-9161-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vona P, Stein BD, Hoover S, et al. . A collaboration to shape an online trauma-responsive school self-assessment. Washington DC Washington DC: 22nd Annual Conference on Advancing School Mental Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringeisen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(9):1179-1189. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vona P, Wilmoth P, Jaycox LH, et al. . A web-based platform to support an evidence-based mental health intervention: lessons from the CBITS web site. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(11):1381-1384. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]