Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of Crohn disease (CD) among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) vs those without HS?

Findings

In this cross-sectional analysis of 51 340 patients, prevalence of CD among patients with HS was 2.0% vs 0.6% among those without HS. Patients with HS have 3 times the odds of having CD as those without HS.

Meaning

Relevant gastrointestinal symptoms among patients with HS warrant additional evaluation.

Abstract

Importance

Limited evidence supports a link between hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and Crohn disease (CD), and this relationship has not been established in the United States.

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence of CD among patients with HS in the United States and to determine the strength of association between the 2 conditions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional analysis of data from 51 340 patients with HS identified using electronic health records data in the Explorys multiple health system data analytics and research platform, which includes data from more than 50 million unique patients across all US census regions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was diagnosis of CD.

Results

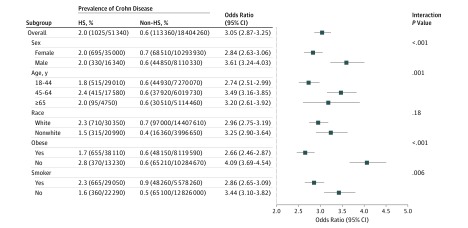

Of the 18 455 660 total population considered, 51 340 had HS (35 000 women). Of these patients with HS, 29 010 (56.5%) were aged 18 to 44 years; 17 580 (34,2%), 45 to 64 years; and 4750 (9.3%), 65 years or older. Prevalence of CD among patients with HS was 2.0% (1025/51 340), compared with 0.6% (113 360/18 404 260) among those without HS (P < .001). Prevalence of CD was greatest among patients with HS who were white (2.3%), aged 45 to 64 years (2.4%), nonobese (2.8%), and tobacco smokers (2.3%). In univariable and multivariable analyses, patients with HS had 3.29 (95% CI, 3.09-3.50) and 3.05 (95% CI, 2.87-3.25) times the odds of having CD, respectively, compared with patients without HS. Crohn disease was associated with HS across all patient subgroups. The association was strongest for men (OR, 3.61; 95% CI, 3.24-4.03), patients aged 45 to 64 years (OR, 3.49; 95% CI, 3.16-3.85), nonobese patients (OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 3.69-4.54), and nonsmokers (OR, 3.44; 95% CI, 3.10-3.82).

Conclusions and Relevance

These data suggest that patients with HS are at risk for CD. Gastrointestinal symptoms or signs suggestive of CD warrant additional evaluation by a gastroenterologist.

This cross-sectional cohort analysis of electronic health records from a large US database evaluates overall and subgroup prevalence of Crohn disease among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in painful nodules and abscesses commonly involving axillary, inguinal, perineal, and inframammary regions. The inherent unpredictability of the disease, both with respect to course and response to treatment, poses substantial challenges for patients.1

Hidradenitis suppurativa shares several clinical features with Crohn disease (CD), and previous observational studies have suggested a link between the 2 conditions. However prevalence estimates for CD among patients with HS are highly variable.2,3,4,5,6,7 Moreover, population-based prevalence estimates and strength of association analyses from outside of Europe are lacking. We sought to evaluate the prevalence of CD among patients with HS in the United States.

Methods

Patient Population

This was a cross-sectional analysis using a multiple health system data analytics and research platform (Explorys) developed by IBM Corporation, Watson Health.8 Clinical information from electronic medical records, laboratories, practice management systems, and claims systems is matched using the single set of Unified Medical Language System ontologies to create longitudinal records for unique patients. The data are standardized and curated according to common controlled vocabularies and classification systems including the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT), Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), and RxNorm.9,10,11,12,13 At present, the Explorys database encompasses 27 participating integrated health care organizations. Data from more than 50 million unique patients, representing approximately 15% of the population across all 4 US census regions, are captured. Patients with all types of insurance as well as those who are self-pay are represented. Ethical review and informed consent were waived, since there are no identifiers associated with any of the patient data.

The SNOMED CT term hidradenitis has 1-to-1 mapping to the ICD-9 code 705.83 and was used to identify patients with HS. In validating the case cohort, we observed a positive predictive value of 79.3% and an accuracy of 90% for diagnosis of HS using a single ICD-9 code for HS.14 This case identification method was previously validated by an independent group, and it was shown to have a positive predictive value of 77%.15 This method has also been used to establish disease burden in the United States.16,17 We used 2 counts of the ICD-9 code 555.x mapped to the corresponding SNOMED CT term to identify the CD cohort. This method has been validated previously with positive predictive values ranging from 84% to 88%.18,19

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was limited to patients 18 years or older whose records were ever entered into the database since 1999, and for whom demographic data on age, sex, race, and body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) were all present. Variables for sex and race were dichotomized into male vs female and white vs nonwhite. Age in years was recorded as a categorical variable within 1 of 3 groups (18-44, 45-64, and ≥65 years). The BMI was dichotomized into obese (≥30.0) vs nonobese (<30.0). Active tobacco smokers were identified using the SNOMED CT terms tobacco user (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code 305.1) or nicotine dependence (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code F17.2).

We obtained population-level counts of the number of patients with and without a diagnosis of CD for each combination of categorical explanatory variables (HS status, sex, age, race, BMI status, and smoking status). Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the characteristics of patients with and without HS. We assessed crude associations between CD and each explanatory variable using separate univariable logistic regression models. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to evaluate the relationship between CD and HS while controlling for sex, age, race, obesity, and smoking status. We assessed potential subgroup differences in the relationship between HS and CD by testing the significance of the interaction between HS and the subgroup variable of interest individually. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

We identified 51 340 patients with HS whose demographic characteristics are described in the Table. The prevalence of CD among patients with HS was 2.0% (1025/51 340), compared with 0.6% (113 360/18 404 260) among those without HS (P < .001). Prevalence of CD was greatest among patients with HS who were white (2.3%), aged 45 to 64 years (2.4%), nonobese (2.8%), and tobacco smokers (2.3%) (Figure). Among nonwhites, the vast majority of patients having both HS and CD were African American.

Table. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| With HS (n = 51 340) | Without HS (n = 18 404 260) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16 340 (31.8) | 8 110 330 (44.1) |

| Female | 35 000 (68.2) | 10 293 930 (55.9) |

| Age, y | ||

| 18-44 | 29 010 (56.5) | 7 270 070 (39.5) |

| 45-64 | 17 580 (34.2) | 6 019 730 (32.7) |

| ≥65 | 4750 (9.3) | 5 114 460 (27.8) |

| Race | ||

| White | 30 350 (59.1) | 14 407 610 (78.3) |

| Nonwhite | 20 990 (40.9) | 3 996 650 (21.7) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30.0) | ||

| Yes | 38 110 (74.2) | 8 119 590 (44.1) |

| No | 13 230 (25.8) | 10 284 670 (55.9) |

| Tobacco smoker | ||

| Yes | 29 050 (56.6) | 5 578 260 (30.3) |

| No | 22 290 (43.4) | 12 826 000 (69.7) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

P < .001 for comparisons between patients with HS and those without HS for all listed characteristics in this table, based on χ2 test.

Figure. Crohn Disease in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS).

Representation of overall and subgroup prevalences and odds for Crohn disease among patients with HS. The odds ratios compare the odds of Crohn disease between patients with and without HS. They were calculated based on a logistic regression model, including terms for sex, age, race, obesity, smoking status, and the interaction between HS and the subgroup variable of interest.

In univariate and multivariable analyses, patients with HS had 3.29 (95% CI, 3.09-3.50) and 3.05 (95% CI, 2.87-3.25) times the odds of having CD, respectively, compared with patients without HS. Crohn disease was associated with HS across all patient subgroups. The association was strongest for men (OR, 3.61; 95% CI, 3.24-4.03), patients aged 45 to 64 years (OR, 3.49; 95% CI, 3.16-3.85), nonobese patients (OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 3.69-4.54), and nonsmokers (OR, 3.44; 95% CI, 3.10-3.82) (Figure).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the prevalence of CD among patients with HS within a US national population-based sample has not previously been reported. In this study, we have observed a prevalence of 2% for CD among patients with HS. The overall likelihood of patients with HS having CD was 3 times greater than among those without HS. This association was present across all subgroups of patients with HS.

Only 2 studies have estimated prevalence of CD among patients with HS within national population samples, one from Denmark2 and the other from Israel,3 where prevalences of both HS16,20 and Crohn disease21,22,23,24,25,26 differ from those in the United States. Moreover, there exist significant differences in HS disease burden among African Americans in the United States compared with HS cohorts outside the United States.16,17 In the Danish study,2 the prevalence of CD among 7732 patients with HS was 0.8%. The adjusted odds of CD among patients with HS were twice that of the general population.2 Patients with HS in the Danish study, who were identified by hospital diagnosis, may have had more comorbidity than patients with HS sampled from a population setting. Moreover, the Danish population was predominantly of Northern European descent, and thus these results may not be generalized to patients of other ethnicities. Interestingly, the prevalence of CD among 3207 Israeli patients with HS was also 0.8%, and the adjusted odds of CD among patients with HS were also twice that of the general population.3 The Israeli population was also limited in race and ethnic heterogeneity. The prevalence and risk estimates in the present study are significantly higher than those reported in European population samples. Given the significant differences in cohorts, it is not clear that Danish and Israeli results can be generalized to patients with HS in the United States.

In another study, prevalence of CD among patients with HS was also estimated not within population samples but within tertiary centers from 3 Western European hospitals.4 In this sample of 1076 patients with HS, the prevalence of CD was 2.5%. However, there was no comparison with a control sample, and thus there was also no regression analysis to provide strength of association between the 2 disorders.

Interestingly, reported prevalence estimates for having HS among patients with CD are several-fold greater than for having CD among patients with HS. In 3 Dutch studies with cohort sizes of 102, 688, and 634 patients with CD, the prevalence of HS was 17%,5 26%,6 and 15%,7 respectively. In these studies, CD cohorts were identified through patient association groups and/or within single centers, and cohorts included patients who self-reported diagnoses of CD and HS. None of these analyses were case matched, and strength of association also could not be established.

The link between HS and inflammatory bowel disease was initially observed in the early 1990s.27 Commonality of clinical features between the 2 conditions has prompted further exploration of the association. Hidradenitis suppurativa and CD are chronic, recurrent, inflammatory disorders in which the epithelia are inhabited by commensal flora. Suppuration and granulomatous inflammation, which represent shared histologic features, may eventuate in fistula and sinus tract formation.1,28,29,30 Their disease burden is similar in the United States,16,17,21 and onset typically occurs in young adulthood in both HS and CD.

Tobacco smoking is linked to both diseases, and smokers also tend to have a more severe course than nonsmokers in both.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 Increased prevalence of spondyloarthropathy has been reported in both groups of patients.39,40 The interleukin-23/T helper cell type 17 pathway and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) appear to be involved in HS as well as CD,34,41,42,43 suggesting an immune-mediated origin for both. Moreover, both HS and CD respond to anti-TNF therapy.44,45 Hidradenitis suppurativa and CD may also have shared genetic risk loci that have a role in disease development.7,46 The pathogenic link between HS and CD is hypothesized to involve an abnormal inflammatory response to commensal bacteria with immune dysregulation, as well as shared susceptibility gene loci.7,46,47 Despite clinical commonalities and potential pathways linking the 2 conditions, there does not appear to be a consistent phenotype among patients with HS and CD.4,6,7,48

Limitations

There are limitations to the present study that warrant consideration when interpreting the results. We could not capture data for patients who did not seek care in health systems included in the database. The extent to which our cohort underestimates HS frequency for this reason, or because of the well-established delays in diagnosis of HS,49 is unknown. Patients with CD may be more likely to seek care, which may also result in detection bias. The extent to which patients with metastatic CD were misclassified as having HS could be determined through codified data. While it is possible that metastatic CD may be underdiagnosed, the occurrence of metastatic CD is nonetheless rare. Therefore, we do not believe that this potential misclassification significantly biased the present analysis. The analysis does not establish a temporal relationship or causal link between HS and CD. We could not assess the influence of disease severity in HS on the strength of the association, nor could we establish a phenotype for patients with HS and CD in this database study.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the present study reports important data describing the association between HS and CD. The prevalence and strength of association reported in this study is based on, to our knowledge, the largest and most ethnically diversified cohort of patients with HS and CD worldwide. The number of patients included in the analysis has allowed an adequate evaluation of an uncommon occurrence for a less common disease, as well as subgroup analyses that allow identification of groups at highest risk. Because the population sample was drawn from various health care settings across all US census regions, this study overcomes selection biases associated with tertiary single or multi-center investigations. We believe these results may be generalized to the US population.

Patients with HS with relevant gastrointestinal symptoms or signs suggestive of CD warrant additional evaluation by a gastroenterologist. Dermatologists and gastroenterologists should be aware of the association described herein to identify patients with HS and CD early in the course of disease to optimize treatment, minimize disease complications, and avoid unnecessary or inappropriate procedures or treatments.

References

- 1.Jemec GB. Clinical practice: hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):158-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeberg A, Jemec GBE, Kimball AB, et al. Prevalence and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(5):1060-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalom G, Freud T, Ben Yakov G, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study of 3,207 patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(8):1716-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deckers IE, Benhadou F, Koldijk MJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(1):49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Zee HH, van der Woude CJ, Florencia EF, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa and inflammatory bowel disease: are they associated? results of a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):195-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Zee HH, de Winter K, van der Woude CJ, Prens EP. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in 1093 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(3):673-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janse IC, Koldijk MJ, Spekhorst LM, et al. Identification of clinical and genetic parameters associated with hidradenitis suppurativa in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(1):106-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IBM Corporation The IBM Explorys Platform: liberate your healthcare data. https://public.dhe.ibm.com/common/ssi/ecm/hp/en/hps03052usen/HPS03052USEN.PDF. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 9.US National Library of Medicine Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT). https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/Snomed/snomed_main.html. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 10.Nelson SJ, Zeng K, Kilbourne J, Powell T, Moore R. Normalized names for clinical drugs: RxNorm at 6 years. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(4):441-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald CJ, Huff SM, Suico JG, et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clin Chem. 2003;49(4):624-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen JJ, Wan TT, Perlin JB. An exploration of the complex relationship of socioecologic factors in the treatment and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in disadvantaged populations. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(4):711-732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foraker RE, Rose KM, Whitsel EA, Suchindran CM, Wood JL, Rosamond WD. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, Medicaid coverage and medical management of myocardial infarction: atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) community surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strunk A, Midura M, Papagermanos V, Alloo A, Garg A. Validation of a case-finding algorithm for hidradenitis suppurativa using administrative coding from a clinical database. Dermatology. 2017;233(1):53-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1144-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):760-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A, Alloo A. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou JK, Tan M, Stidham RW, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic codes for identifying patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(10):2406-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thirumurthi S, Chowdhury R, Richardson P, Abraham NS. Validation of ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes for inflammatory bowel disease among veterans. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(9):2592-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinding GR, Miller IM, Zarchi K, Ibler KS, Ellervik C, Jemec GB. The prevalence of inverse recurrent suppuration: a population-based study of possible hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(4):884-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1424-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1785-1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46-54.e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL; ECCO-EpiCom . The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(4):322-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, et al. ; ECCO-EpiCom . East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63(4):588-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zvidi I, Hazazi R, Birkenfeld S, Niv Y. The prevalence of Crohn’s disease in Israel: a 20-year survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(4):848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostlere LS, Langtry JA, Mortimer PS, Staughton RC. Hidradenitis suppurativa in Crohn’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125(4):384-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1641-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, Ansell ID, Douglas-Jones AG, Williams GT. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn’s disease. Histopathology. 1993;23(2):111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy MK, Appleton MA, Delicata RJ, Sharma AK, Williams GT, Carey PD. Probable association between hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: significance of epithelioid granuloma. Br J Surg. 1997;84(3):375-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the USA [published online September 27, 2017]. Br J Dermatol. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazary M, van der Zee HH, Prens EP, Folkerts G, Boer J. Pathogenesis and pharmacotherapy of Hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;672(1-3):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, Lapins J. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):831-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2066-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, et al. ; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) . The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(1):63-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenfeld G, Bressler B. The truth about cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1407-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higuchi LM, Khalili H, Chan AT, Richter JM, Bousvaros A, Fuchs CS. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1399-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan SS, Luben R, Olsen A, et al. Body mass index and the risk for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: data from a European prospective cohort study (The IBD in EPIC Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):575-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richette P, Molto A, Viguier M, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa associated with spondyloarthritis—results from a multicenter national prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(3):490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gionchetti P, Calabrese C, Rizzello F. Inflammatory bowel diseases and spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2015;93:21-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(4):790-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Increased serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: is there a basis for treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha agents? Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(6):601-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314(5804):1461-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):619-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cholapranee A, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ananthakrishnan AN. Systematic review with meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of biologics for induction and maintenance of mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(10):1291-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Zee HH, Horvath B, Jemec GB, Prens EP. The association between hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: in search of the missing pathogenic link. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(9):1747-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC. Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinol. 2010;2(1):9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yadav S, Singh S, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):65-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1546-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]