This population-based study evaluates the association between marital status and T stage at the time of presentation and the decision for sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with early-stage melanoma included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of marital status with T stage at presentation and management of early-stage melanoma?

Findings

In this analysis of 52 063 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, married patients more commonly presented with T1a tumors, whereas widowed patients were more likely to present with T4b tumors. In addition, married patients were more likely to undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy for lesions with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm.

Meaning

These findings support increased consideration of spousal training for partner skin examination and perhaps more frequent screening for unmarried patients.

Abstract

Importance

Early detection of melanoma is associated with improved patient outcomes. Data suggest that spouses or partners may facilitate detection of melanoma before the onset of regional and distant metastases. Less well known is the influence of marital status on the detection of early clinically localized melanoma.

Objective

To evaluate the association between marital status and T stage at the time of presentation with early-stage melanoma and the decision for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in appropriate patients.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, population-based study used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database of 18 population-based registered cancer institutes. Patients with cutaneous melanoma who were at least 18 years of age and without evidence of regional or distant metastases and presented from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2014, were identified for the study. Data were analyzed from September 27 to December 5, 2017.

Exposure

Marital status, categorized as married, never married, divorced, or widowed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinical T stage at presentation and performance of SLNB for lesions with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm.

Results

A total of 52 063 patients were identified (58.8% men and 41.2% women; median age, 64 years; interquartile range, 52-75 years). Among married patients, 16 603 (45.7%) presented with T1a disease, compared with 3253 never married patients (43.0%), 1422 divorced patients (39.0%), and 1461 widowed patients (32.2%) (P < .001). Conversely, 428 widowed patients (9.4%) presented with T4b disease compared with 1188 married patients (3.3%) (P < .001). The association between marital status and higher T stage at presentation remained significant among never married (odds ratio [OR], 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39; P < .001), divorced (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.30-1.47; P < .001), and widowed (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.60-1.81; P < .001) patients after adjustment for various socioeconomic and patient factors. Independent of T stage and other patient factors, married patients were more likely to undergo SLNB in lesions with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm, for which SLNB is routinely recommended, compared with never married (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.53-0.65; P < .001), divorced (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76-0.99; P = .03), and widowed (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.62-0.76; P < .001) patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

Marital status is associated with earlier presentation of localized melanoma. Moreover, never married, divorced, and widowed patients are less likely to undergo SLNB for appropriate lesions. Marital status should be considered when counseling patients for melanoma procedures and when recommending screening and follow-up to optimize patient care.

Introduction

Malignant melanoma is increasing in incidence and is now the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1,2,3,4 This skin cancer is commonly identified at an early stage, with clinical stages I and II melanoma constituting nearly 85% of all newly diagnosed cases.5 Early detection of melanoma is critical because it is associated with improved patient outcomes; 5-year survival is reported to be greater than 98% for patients diagnosed with stage I disease, compared with 62% for stage III disease.6,7,8 Among patients with clinically localized melanoma, a wide range in melanoma-specific survival is characterized by T stage and ulceration status.9 Survival for stage IIc disease, for example, is comparable to that for stage III disease, with a 10-year survival rate as low as 32% in this subgroup.10 Identification of factors associated with early detection of melanoma may therefore be critically important to improving melanoma outcomes.

Various socioeconomic factors have been increasingly recognized as having significant influence on oncologic outcomes.11,12 In particular, marital status has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes in breast, colon, and renal cancer.13,14,15,16 For melanoma specifically, marital status has also been found to be associated with the risk of regional and/or distant metastases at diagnosis, with unmarried patients presenting with more advanced disease.17,18 However, whether any association exists between marital status and T stage at presentation among patients with clinically localized disease has not been determined. This situation has potentially important clinical implications because of the wide variation of melanoma-specific survival as stratified by T stage. Moreover, little is known regarding the influence of marital status with respect to management decisions in early-stage melanoma.

In this study, we evaluated the association between marital status and T stage at presentation (defined using the Seventh Edition American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging [AJCC] criteria) for cutaneous malignant melanoma in a cohort of patients from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. We hypothesized that married patients would have an earlier T stage at presentation. Because social factors have been shown to affect adherence to clinical guidelines,19,20 we also investigated the association between marital status and receipt of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for patients with tumors with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm, for whom SLNB is routinely recommended.

Methods

The SEER database represents roughly 30% of the US population and uses data from 18 population-based registered cancer institutes (https://seer.cancer.gov). The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania, which waived the need for informed consent for use of SEER data.

Patients included for this study had a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of melanoma and were at least 18 years of age with marital status recorded and known SLN status. Included patients received a diagnosis from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2014; these dates were chosen for consistency in reporting of pathologic variables following the 2009 staging system update by the AJCC. Patients were excluded if they had clinical nodal disease or metastatic disease at the time of presentation. Patients were also excluded if it was unknown whether the SLNB was performed.

The primary outcome measured was clinical T stage at time of presentation (Seventh Edition AJCC criteria), which was treated as an ordinal variable (ordered as T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, T3a, T3b, T4a, or T4b). The primary exposure of interest was marital status (defined as married, never married, divorced, or widowed). Marital status is a self-reported variable that has consistently been reported in the SEER data set. In addition to the marital status categories used in this study, patients can be categorized as separated or having an unmarried or domestic partner. These categories were excluded from analysis because they accounted for less than 1% of the data. Covariates included for analysis were age, sex, primary site (trunk, extremity, or head and/or neck), urban or rural location of residence (urban [metropolitan], urban [nonmetropolitan], or rural), state of residence, income (defined as median household income in the patient’s county), and educational level (defined as percentage of population older than 25 years in the patient’s county with at least a high school educational level). In secondary analysis examining the association between marital status and rates of SLNB, the outcome evaluated was whether SLNB was performed, treated as a binary variable.

Data were analyzed from September 27 to December 5, 2017. Descriptive statistics are presented for categorical variables as frequencies and for continuous variables as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). We used the χ2 test to evaluate for significant differences in distribution of T stage at presentation by marital status. We then performed multivariable ordinal logistic regression to evaluate the association between marital status and higher T stage at presentation after adjusting for potential confounders. A multivariable model was created using all variables, and those that were nonsignificant (P > .05) were sequentially removed to create a reduced multivariable model. The odds ratios (ORs) reported in this ordinal regression analysis may be interpreted as the increased odds of presenting with a T stage higher by 1 level. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression were used to evaluate the association between marital status and performance of SLNB. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 14; StataCorp).21

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 52 063 patients with cutaneous melanoma who met study criteria were identified in SEER from 2010 to 2014 (58.8% men and 41.2% women; median age, 64 years; interquartile range, 52-75 years). Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Most patients were married (36 307 [69.7%]). Others were never married (7570 [14.5%]), divorced (3650 [7.0%]), or widowed (4536 [8.7%]). The oldest group of patients was widowed, with a median age of 82 years (IQR, 75-87 years), followed by 64 years (IQR, 53-74 years) for married patients, 62 years (IQR, 53-71 years) for divorced patients, and 54 years (IQR, 38-66 years) for never married patients (P < .001). Married patients were more commonly male (23 118 [63.7%]), whereas male patients constituted a minority in the widowed group (1728 [38.1%]; P < .001). Median income was higher for married and never married patients ($47 200 for both; IQRs, $38 700-$51 600 and $38 700-$51 500, respectively) than for divorced and widowed patients ($46 500 for both; IQRs, $38 200-$51 300 for both) (P < .001). Never married patients were most likely to reside in metropolitan areas (6880 of 7571 [90.9%]; P < .001).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Cohorta.

| Characteristic | Married (n = 36 307) | Never Married (n = 7570) | Divorced (n = 3650) | Widowed (n = 4536) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 64 (53-74) | 54 (38-66) | 62 (53-71) | 82 (75-87) | NA |

| Male, No. (%) | 23 118 (63.7) | 4011 (53.0) | 1753 (48.0) | 1728 (38.1) | <.001 |

| Site, No. (%) | |||||

| Trunk | 12 002 (33.1) | 2707 (35.8) | 1224 (33.5) | 955 (21.1) | <.001 |

| Extremity | 16 000 (44.1) | 3498 (46.2) | 1793 (49.1) | 2208 (48.7) | |

| Head and/or neck | 8305 (22.9) | 1365 (18.0) | 633 (17.3) | 1373 (30.3) | |

| T stage at presentation, No. (%) | |||||

| T1a | 16 603 (45.7) | 3253 (43.0) | 1422 (39.0) | 1461 (32.2) | <.001 |

| T1b | 7466 (20.6) | 1610 (21.3) | 728 (19.9) | 780 (17.2) | |

| T2a | 5284 (14.6) | 1107 (14.6) | 628 (17.2) | 671 (14.8) | |

| T2b | 1253 (3.5) | 243 (3.2) | 145 (4.0) | 212 (4.7) | |

| T3a | 2111 (5.8) | 452 (6.0) | 253 (6.9) | 388 (8.6) | |

| T3b | 1445 (4.0) | 325 (4.3) | 177 (4.8) | 344 (7.6) | |

| T4a | 957 (2.6) | 220 (2.9) | 112 (3.1) | 252 (5.6) | |

| T4b | 1188 (3.3) | 360 (4.8) | 185 (5.1) | 428 (9.4) | |

| Urban/rural, No. (%) | |||||

| Urban (metropolitan) | 31 994 (88.1) | 6880 (90.9) | 3175 (87.0) | 3923 (86.5) | <.001 |

| Urban (nonmetropolitan) | 3833 (10.6) | 616 (8.2) | 415 (11.4) | 539 (11.9) | |

| Rural | 530 (1.5) | 74 (1.0) | 60 (1.6) | 74 (1.6) | |

| Income, median (IQR), $ | 47 200 (38 700-51 600) | 47 200 (38 700-51 500) | 46 500 (38 200-51 300) | 46 500 (38 200-51 300) | <.001 |

| Educational level, median (IQR), % | 83 (86-79) | 83 (86-77) | 83 (86-77) | 83 (16-77) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Calculated using the χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for others.

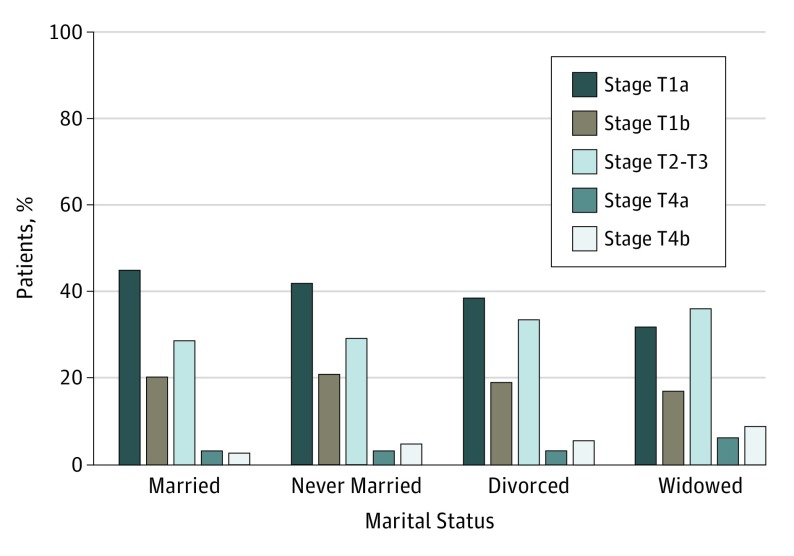

Association of Marital Status With T Stage at Presentation

Distribution of T stage at presentation varied significantly by marital status (Figure 1). Married patients more commonly presented with T1a tumors (16 603 [45.7%]) compared with never married (3253 [43.0%]), divorced (1422 [39.0%]), and widowed (1461 [32.2%]) patients (P < .001). Conversely, widowed patients were more likely to present with T4 disease (T4a, 252 [5.6%]; T4b, 428 [9.4%]) compared with married (T4a, 957 [2.6%]; T4b, 1188 [3.3%]), never married (T4a, 220 [2.9%]; T4b, 360 [4.8%]), and divorced (T4a, 112 [3.1%]; T4b, 185 [5.1%]) patients (P < .001).

Figure 1. Distribution of T Stage at Presentation of Melanoma by Marital Status.

Married patients were more likely to present with earlier T stage tumors, whereas widowed patients were more likely to present with T4 tumors.

In univariate ordinal logistic regression, patients who were never married (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.18), divorced (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.26-1.42), and widowed (OR 2.09; 95% CI, 1.97-2.21) were more likely to present with a higher T stage than married patients (P < .001 for all) (Table 2). Other factors significantly associated with T stage at presentation included age (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01-1.01; P < .001), male sex (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18-1.26; P < .001), primary tumor site in an extremity (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.27-1.37; P < .001) or the head and/or neck (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.38; P < .001), income (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99-0.99; P < .001), and educational level (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .006). After adjustment for these factors, never married (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39), divorced (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.30-1.47), and widowed (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.60-1.81) patients remained more likely to present with a later T stage in a multivariable model compared with married patients (P < .001 for all). In addition, the possibility of interaction of sex and the association between marital status and T stage was assessed. This interaction term was not significant for male sex with never married (OR, 0.96; P = .39), divorced (OR, 1.06; P = .37), or widowed (OR, 0.93; P = .26) (joint test of significance, χ23 = 3.03; P = .39).

Table 2. Factors Associated With Higher T Stage at Presentation in Ordered Logistic Regressiona.

| Clinicopathologic Factor | Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | Reduced Multivariable Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Never married | 1.12 (1.07-1.18) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.26-1.39) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.26-1.39) | <.001 |

| Divorced | 1.34 (1.26-1.42) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.30-1.47) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.30-1.47) | <.001 |

| Widowed | 2.09 (1.98-2.21) | <.001 | 1.70 (1.60-1.81) | <.001 | 1.70 (1.60-1.81) | <.001 |

| Age, y | NA | NA | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | <.001 | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | <.001 |

| Male | NA | NA | 1.22 (1.18-1.26) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.18-1.26) | <.001 |

| Site | ||||||

| Trunk | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Extremity | NA | NA | 1.32 (1.27-1.37) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.27-1.37) | <.001 |

| Head and/or neck | NA | NA | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) | <.001 |

| Income, $10 000 | NA | NA | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | <.001 |

| Educational level | NA | NA | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .02 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .006 |

| Urban/rural | ||||||

| Urban (metropolitan) | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA |

| Urban (nonmetropolitan) | NA | NA | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | .29 | NA | NA |

| Rural | NA | NA | 0.97 (0.85-1.12) | .72 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Odds ratio in ordered logistic regression is interpreted as the increased odds of presenting with 1 T stage higher.

Calculated using the χ2 test.

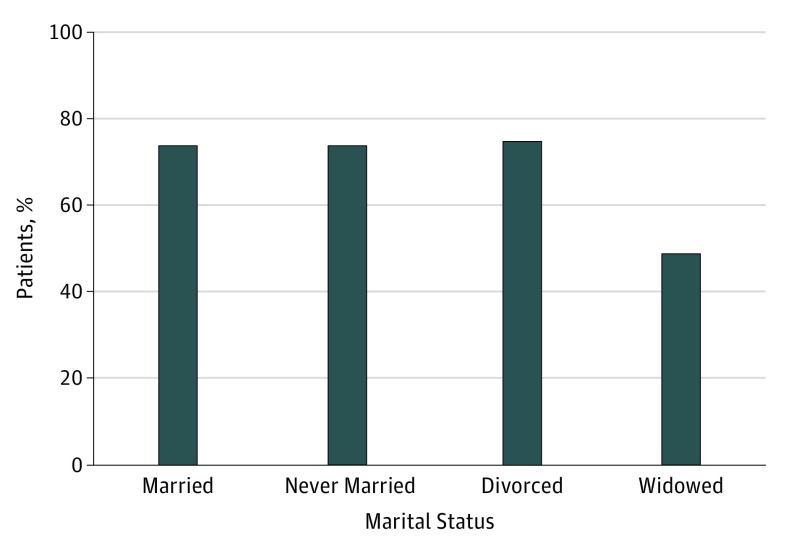

Association of SLNB With Patient Marital Status

Rates of SLNB for lesions with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm are shown in Figure 2. Widowed patients were the least likely to undergo SLNB (1115 [48.8%]) compared with divorced patients (1121 [74.9%]), married patients (9021 [74.0%]), or never married patients (1986 [73.6%]). After adjusting for age, primary tumor site, and T stage, married patients were more likely to undergo SLNB compared with never married (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.53-0.65; P < .001), divorced (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76-0.99; P = .03), and widowed (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.62-0.76; P < .001) patients. Clinicopathologic factors associated with performance of SLNB for lesions with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm are presented in Table 3. These associations did not change with inclusion of income, educational level, or metropolitan vs rural region in the model.

Figure 2. Rates of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB) for Tumors With Breslow Thickness Greater Than 1 mm by Marital Status.

Widowed patients were least likely to undergo SLNB, whereas divorced patients were most likely to undergo SLNB.

Table 3. Factors Associated With Performance of SLNB for Lesions With Breslow Thickness Greater Than 1 mm in Logistic Regression.

| Clinicopathologic Factor | Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Never married | 1.69 (1.54-1.89) | .75 | 0.59 (0.53-0.65) | <.001 |

| Divorced | 1.05 (0.93-1.19) | .42 | 0.87 (0.76-0.99) | .03 |

| Widowed | 0.34 (0.31-0.34) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.62-0.76) | <.001 |

| Age, y | NA | NA | 0.95 (0.94-0.95) | <.001 |

| Site | ||||

| Trunk | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Extremity | NA | NA | 1.23 (1.13-1.34) | <.001 |

| Head and/or neck | NA | NA | 0.54 (0.49-0.59) | <.001 |

| T stage | ||||

| T2a | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | |

| T2b | NA | NA | 1.15 (1.02-1.31) | .03 |

| T3a | NA | NA | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | .04 |

| T3b | NA | NA | 1.19 (1.07-1.34) | .001 |

| T4a | NA | NA | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | .04 |

| T4b | NA | NA | 0.78 (0.70-0.87) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Calculated using the χ2 test.

Among patients with tumors with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm who underwent SLNB, the rate of SLN positivity was significantly lower among married patients (1348 [14.9%]) compared with never married (376 [18.9%]), divorced (199 [17.8%]), and widowed (175 [15.7%]) patients (P < .001 for all). After adjustment for T stage, tumor site, and patient age, the rate of SLN positivity was no longer significantly different for never married (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.88-1.15; P = .93), divorced (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34; P = .15), and widowed (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.95-1.38; P = .15) patients. Higher T stage, younger age, and nontrunk primary site were independently associated with SLN positivity.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the association between marital status and T stage at the time of presentation for early-stage melanoma. Because melanoma-specific survival is directly influenced by T stage for clinically localized melanoma, understanding which factors may influence the earlier detection of these lesions is important.22 Although previous studies have shown an association between marital status and higher likelihood of regional or distant disease at presentation, this study examines the association between marital status and T stage among patients with clinically localized tumors.17,18 This study also investigates the association between marital status and the receipt of SLNB in appropriately selected patients. Because SLNB is routinely recommended in patients with melanoma and Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm, understanding the role that social factors such as marital status play in adherence to these guidelines may help clinicians in counseling patients.

In the present study, we found that married patients presented with significantly lower T stage melanomas compared with patients who were never married, divorced, or widowed. Among married patients, 45.7% had T1a tumors at the time of presentation compared with 43.0% of never married, 39.0% of divorced, and 32.2% of widowed patients. Conversely, widowed patients presented more commonly with lesions larger than 4 mm compared with other marital status patient groups, with widowed patients demonstrating a nearly 3 times higher rate of T4 lesions compared with married patients (9.4% vs 3.3%). These associations of marital status with T stage remained significant after adjustment for important clinical and socioeconomic factors, including age, sex, primary tumor site, income, and educational level. In addition, widowed patients were least likely to undergo SLNB for lesions greater than 1 mm in Breslow thickness (for which SLNB is routinely recommended), a pattern that persisted after adjustment for age, T stage, and anatomical site.

Married patients are more likely to present with earlier clinically localized melanoma and to proceed with SLNB according to guidelines. Spouses likely facilitate early detection of melanomas by assisting in identification of pigmented lesions that may have otherwise gone unnoticed. Spouses may also provide support and encouragement to see a physician for evaluation. Detection of primary melanomas at an early T stage is advantageous because increasing tumor thickness (T stage) is highly correlated with melanoma-specific survival and is one of the most important prognostic factors for mortality.22,23 Thus, married patients are likely to receive a better prognosis because of earlier surgical management. In addition, higher T stage lesions may require larger excisional margins and may be recommended for SLNB, which may result in additional surgical morbidity. The finding that married patients are more likely than never married, divorced, or widowed patients to undergo SLNB when appropriate may be associated with the spouse’s role in supporting the patient and engaging in further discussion. In addition, unmarried patients may have more limited resources for the procedure, which would make it more challenging to undergo SLNB. For example, without a spouse or partner, patients may have difficulty facilitating travel to and from the procedure, and they may not have anyone to assist them in postprocedure care.14

In addition to the finding that married patients are more likely to undergo SLNB for lesions when it is recommended, married patients had a significantly lower rate of SLN positivity than did other marital status groups. This finding is likely attributable in large part to the presentation with an earlier T stage of married patients compared with other groups, because the association did not persist after adjustment for T stage, tumor site, and patient age.

Results from the present study are concordant with those of previous literature on the association between marital status and stage of melanoma diagnosis. McLaughlin and colleagues18 reported that never married, divorced, and widowed patients were more likely to present with regional or distant metastatic disease than their married counterparts. Smaller studies based on Florida and California residents dichotomized patients into married and unmarried groups and found that married patients were more likely to present with late-stage melanoma.17,24 Of importance, the association between marital status and detection of early clinically localized melanoma has been unreported. This association is very clinically relevant because survival for patients with stage IIC melanoma can be just as poor as that for patients with regional disease.22 The results of the present study are also consistent with findings from a study from the MD Anderson Cancer Center25 that showed that single, divorced, and widowed patients were more likely to deviate from the recommended surgical treatment for melanoma (including wide local excision, SLNB, and completion lymph node dissection) than were their married counterparts. Although we speculate that this may be attributable to better social support or encouragement, further study is needed to better understand this finding.

This study has important implications for counseling patients and recommending frequency of follow-up surveillance. Clinicians may, for instance, recommend that unmarried patients initiate regular skin examinations at an earlier age and continue them more frequently to detect lesions at an earlier stage. For married patients, encouragement of partners to be present at clinic appointments and undergo basic training for performing a skin examination could perhaps further increase early detection of primary lesions. A randomized clinical trial of partner-assisted structured skin examination found that patients and partners who underwent structured skin examination training identified more new melanomas than patients without the instruction and were comfortable in their ability to do so.26,27 This study may support confirmation of these prospective results using population-level data. Physicians with increased awareness of reduced adherence with SLNB in unmarried patients may also emphasize the importance of having a friend or family member attend visits when SLNB is discussed. Including these persons may improve adherence to guidelines.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are inherent to its retrospective nature. Whether unmarried patients are in an unmarried relationship or are living alone is unknown. Misclassification of data is possible attributable to inaccurate coding. However, we have no reason to suspect that this would occur in any particular direction for T stage by marital status, because misclassification would likely be nondifferential in nature and likely bias toward the null. Although adjustment was made for important socioeconomic variables, such as income and educational level, other unobserved variables for which we did not account may confound the association between marital status and T stage at presentation. Finally, with respect to adherence with receipt of SLNB, the nature of the data does not allow us to determine whether the differences observed stratified by marital status were driven by differential recommendations by clinicians among groups or patient-derived differences in decision making among marital status groups or a combination of both—a topic that merits further study.

Conclusions

In this cohort of patients with clinically localized melanoma, marital status was found to be significantly associated with T stage at presentation, with married patients presenting with earlier-stage lesions, a finding that persisted after adjustment for important socioeconomic factors. Furthermore, married patients were more likely to be adherent with current guidelines and undergo SLNB for lesions greater than 1 mm in Breslow thickness. Last, among patients with tumors with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm who did undergo SLNB, SLN positivity was significantly lower among married patients. However, this finding did not persist after adjustment for T stage, tumor site, and patient age, supporting the notion that marital status plays an important role in earlier detection of primary melanoma. These findings support increased consideration of spousal training for partner skin examination and perhaps more frequent screening for unmarried patients, practical interventions with potentially significant clinical implications.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):106-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller AC, Swetter SM, Brooks K, Demierre MF, Yaroch AL. Screening, early detection, and trends for melanoma: current status (2000-2006) and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(4):555-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garbe C, Leiter U. Melanoma epidemiology and trends. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(1):11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tung R, Vidimos A Melanoma. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/dermatology/cutaneous-malignant-melanoma/. August 2010. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 6.Bataille V. Early detection of melanoma improves survival. Practitioner. 2009;253(1722):29-32, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conic RZ, Cabrera CI, Khorana AA, Gastman BR. Determination of the impact of melanoma surgical timing on survival using the National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):40-46.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2014. 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Updated June 28, 2017. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 9.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GC, Tseng CW. Six strategies to identify and assist patients burdened by out-of-pocket prescription costs. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(5):433-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wich LG, Ma MW, Price LS, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and sociodemographic factors on melanoma presentation among ethnic minorities. J Community Health. 2011;36(3):461-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghi A, Corazza M, Virgili A, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and district of residence on cutaneous malignant melanoma prognosis: a survival study on incident cases between 1991 and 2011 in the province of Ferrara, northern Italy. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(6):619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Wilson SE, Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS. Marital status and colon cancer outcomes in US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries: does marriage affect cancer survival by gender and stage? Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(5):417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3869-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q, Gan L, Liang L, Li X, Cai S. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(9):7339-7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Wang L, Kabirov I, et al. Impact of marital status on renal cancer patient survival. Oncotarget. 2017;8(41):70204-70213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, Swetter SM. California Medicaid enrollment and melanoma stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin JM, Fisher JL, Paskett ED. Marital status and stage at diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: results from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, 1973-2006. Cancer. 2011;117(9):1984-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedi RB, Ayotte B, Edelman D, Bosworth HB. The association of emotional well-being and marital status with treatment adherence among patients with hypertension. J Behav Med. 2008;31(6):489-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnadoux F, Le Vaillant M, Goupil F, et al. ; IRSR sleep cohort group . Influence of marital status and employment status on long-term adherence with continuous positive airway pressure in sleep apnea patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software , Release 14 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

- 22.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17 600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3622-3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soong SJ, Ding S, Coit D, et al. ; AJCC Melanoma Task Force . Predicting survival outcome of localized melanoma: an electronic prediction tool based on the AJCC melanoma database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(8):2006-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Durme DJ, Ferrante JM, Pal N, Wathington D, Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC. Demographic predictors of melanoma stage at diagnosis. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(7):606-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Population-based assessment of surgical treatment trends for patients with melanoma in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6054-6062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson JK, Wayne JD, Martini MC, Hultgren BA, Mallett KA, Turrisi R. Early detection of new melanomas by patients with melanoma and their partners using a structured skin self-examination skills training intervention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(9):979-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JK, Hultgren B, Mallett K, Turrisi R. Self-confidence and embarrassment about partner-assisted skin self-examination for melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(3):342-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]