Key Points

Question

What examination practices and patient attitudes are associated with the detection of thinner nodular melanoma (NM) and superficial spreading melanoma (SSM)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional pooled analysis of 685 patients, whole-body physician skin examination was associated with thinner NM and SSM, while skin self-examination was associated with thinner SSM only. Increased skin cancer awareness was associated with thinner NM.

Meaning

Because NM is typically detected at greater than 2 mm thickness, understanding these factors for earlier detection may improve survival.

This cross-sectional pooled analysis analyzes the association between skin examination practices and diagnosis with thin nodular or superficial spreading melanoma.

Abstract

Importance

Early melanoma detection strategies include skin self-examination (SSE), physician skin examination (PSE), and promotion of patient knowledge about skin cancer.

Objective

To investigate the association of SSE, PSE, and patient attitudes with the detection of thinner superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) and nodular melanoma (NM), the latter of which tends to elude early detection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based, multicenter study identified patients with newly diagnosed cutaneous melanoma at 4 referral hospital centers in the United States, Greece, and Hungary. Among 920 patients with a primary invasive melanoma, 685 patients with SSM or NM subtype were included.

Interventions

A standardized questionnaire was used to record sociodemographic information, SSE and PSE practices, and patient perceptions in the year prior to diagnosis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Data were analyzed according to histologic thickness, with a 2-mm cutoff for thinner SSM and NM.

Results

Of 685 participants (mean [SD] age, 55.6 [15.1] years; 318 [46%] female), thinner melanoma was detected in 437 of 538 SSM (81%) and in 40 of 147 NM (27%). Patients who routinely performed SSE were more likely to be diagnosed with thinner SSM (odds ratio [OR], 2.61; 95% CI, 1.14-5.40) but not thinner NM (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 0.84-6.80). Self-detected clinical warning signs (eg, elevation and onset of pain) were markers of thicker SSM and NM. Whole-body PSE was associated with a 2-fold increase in detection of thinner SSM (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.16-4.35) and thinner NM (OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.05-6.82). Patient attitudes and perceptions focusing on increased interest in skin cancer were associated with the detection of thinner NM.

Conclusions and Relevance

Our findings underscore the importance of complementary practices by patients and physicians for the early detection of melanoma, including regular whole-body PSE, SSE, and increased patient awareness.

Introduction

In patients with cutaneous melanoma, tumor thickness is the strongest independent predictor of survival. Twenty-year survival approaches 96% in patients with thin melanoma (Breslow thickness ≤1 mm), while thicker melanomas are associated with higher mortality risk.1,2 In 6 populations of European heritage, predictive models suggest continuous increases in incidence of cutaneous melanoma through 2031, which highlights the need for melanoma control strategies.3

Widespread early detection efforts have contributed to the rapidly rising incidence of thin melanoma in Australia,4 the United States,5 and Europe.6,7 Factors associated with the detection of thin melanoma (≤1 mm) in a multicenter observational US study showed that patients who underwent a full-body physician skin examination (PSE) in the year before diagnosis were twice as likely to have thin melanoma.8 In a subsequent study of Greek patients, thin melanoma was associated with female sex, married status, and performing careful skin self-examination (SSE).9 In all of these studies, however, there are limited data correlating these diagnostic and behavioral factors with different histologic subtypes of cutaneous melanoma, including the most common, superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), and the most commonly fatal, nodular melanoma (NM).

In a population-based, prospective melanoma registry study among 26 736 patients with thin melanoma (≤1 mm), NM subtype was among the factors associated with increased risk of death.2,10 Because NM accounts for 40% to 50% of melanomas with Breslow thickness greater than 2 mm11,12 and is often described as a rapidly growing tumor,13 there may be a narrower window for detection of NM in its thinner phases. In general, NM exhibits distinct characteristics from SSM: it occurs more frequently in older men,11,14 has higher growth kinetics and mitotic rate, and presents with clinical characteristics that tend to elude early detection (eg, amelanosis, symmetry, and border regularity).11,12,13,15,16 Few studies have assessed factors associated with the detection of thinner NM (≤2 mm).12,14,17,18

The aim of this multicenter study was to investigate skin examination and behavioral patterns in patients with thinner vs thicker melanoma and examine how they may differ between NM and SSM subtypes.

Methods

Participation Centers and Patients

Pooled data were collected from 3 studies that used the same protocol among 4 dermatology-based melanoma referral centers at Stanford University and the University of Michigan in the United States,8 at the University of Athens and collaborating centers in Greece,9 and at the University of Szeged in Hungary from January 2015 to December 2015. Institutional review board and ethics approval and informed patient consent were obtained at all sites. The participants were consecutive, newly diagnosed, predominantly Caucasian patients 18 years or older with primary invasive melanoma. As the study aimed to explore differences in tumor thickness at diagnosis between NM and SSM, only patients with these histopathological subtypes were included. Patients with melanoma in situ, multiple primary melanomas, or noncutaneous melanoma were excluded.

Patient Interview and Data Collection

All questions concerned the year before diagnosis. The same structured questionnaire was used, based on the study by Swetter et al,8 after translation into Greek and Hungarian. A sample of randomly selected questions were translated back to English to validate the accuracy of the translation. The dermatologist or an appropriately trained physician, nurse, or research assistant administered the questionnaires. Investigated variables included demographic information (age, sex, education, and marital status); phenotypic characteristics (skin color and skin reaction to first sun exposure during summer); and melanoma history (previous melanoma and family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative). Questionnaire items included attitudes and perceptions reflecting melanoma awareness, SSE and PSE practices, and mode of melanoma discovery.

We categorized SSE in 3 ways as previously described in the study by Pollitt et al19: (1) routine examination of any of 13 specific body areas, (2) frequency of mole examination, and (3) use of a picture aid illustrating a melanoma tumor. The first measure asked patients to identify which of 13 areas of their skin they routinely examined. This measure was also dichotomized by whether patients routinely examined their skin on some and/or all areas or no areas. The second measure assessed the frequency with which patients carefully examined their moles, categorized as every 1 to 2 months, every 6 months, every year, and never. The third item assessed whether patients ever used a picture of melanoma to help them look at their skin.

Patients were asked about self-detected clinical changes in the lesion that turned out to be melanoma (color, border, thickness/elevation, pain, itching, bleeding, different than it used to be), whether they could easily see the lesion, and whether they noticed a change in any of their moles.

Physician skin examination in the year before diagnosis was assessed, as previously described in the study by Swetter et al,8 by asking patients whether they had a usual place to go when sick or in need of health advice, whether they had a physician for routine care, whether a physician examined their skin for cancer during any visits, why the physician examined their skin for cancer, and whether the physician examined the patient’s whole skin or just a particular lesion.

In addition, 1 composite variable assessed successful SSE as self-detection of thinner melanoma in patients who regularly performed SSE. A second variable assessed successful PSE as the detection of thinner melanoma by physicians in patients who received a PSE.

Clinical examination of patients was conducted by a dermatologist who provided the count of total nevi and clinically atypical (dysplastic) nevi. Anatomic location and histopathological characteristics of melanoma were classified according to the 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging and classification guidelines.1 Accepted criteria for histopathologic classification of SSM vs NM subtype were used.20

For thinner NM, a cutoff of 2 mm or less was used because only 4 NM in the entire data set were diagnosed with a thickness of 1 mm or less, which precluded any reliable analysis of the examined factors. For thinner SSM, the primary outcome of Breslow thickness of less than or equal to 2 mm was used to define thin melanoma to be consistent with the definition of thinner NM. Thinner SSM were further investigated in a secondary analysis with the use of a cutoff of less than or equal to 1 mm, while maintaining the cutoff of 2 mm or less for thinner NM.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the characteristics of patients were calculated. Continuous data are presented as mean (SD) for normally distributed variables and were compared using the student t test. Categorical data are presented as numbers and frequencies.

Association between the 2 melanoma subtypes and each variable was investigated by exploratory analysis with a χ2 test or a Fisher exact test, as appropriate, and with univariate logistic regression analysis. To investigate the association of thinner melanoma with every variable, multiple logistic regression analysis was carried out with different models for the outcomes of NM or SSM melanoma subtypes, including statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis for SSM was adjusted for age, sex, and education, and multivariate analysis for NM included patient age and sex, as no factors were statistically significant in the univariate analysis for thinner NM. Adjustment for country (US, Greece, or Hungary) showed similar results for NM and SSM, so this variable was not included in the final parsimonious model (data not shown).

As the detection of thinner melanoma was the outcome of this study, the odds ratios are reported as the odds of thinner melanoma compared with those of thicker melanoma. All P values were 2-sided, and the significance level was P < .05. Analyses were carried out using STATA statistical software, version 13 (StataCorp).

Results

Patient and Melanoma Characteristics

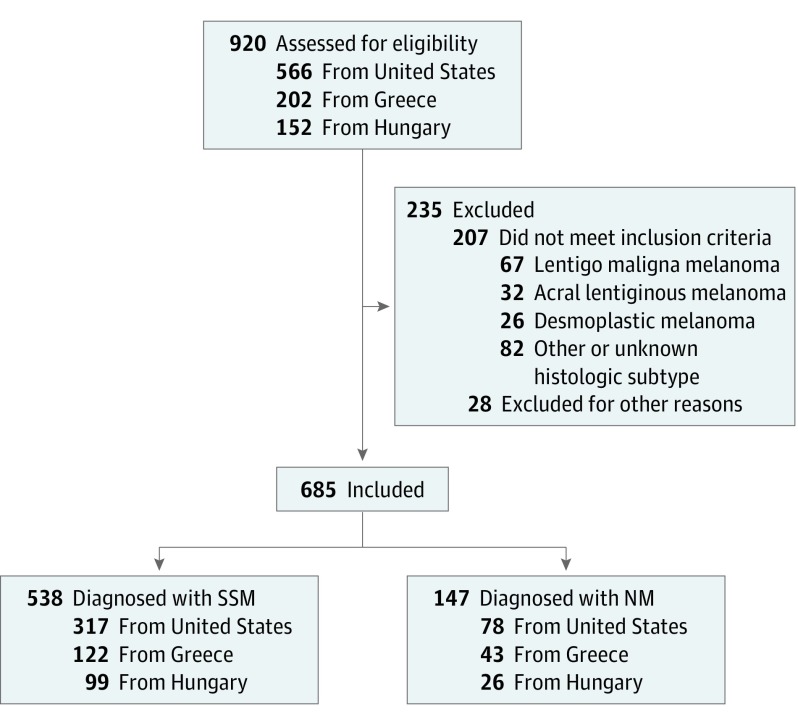

Overall, there were 920 patients with a cutaneous melanoma diagnosis. Of these, 235 patients were excluded (207 with melanoma of other histological types, and 28 for missing or “don’t know” answers in variables of interest). Exclusion rates per country were as follows: United States, 30%; Greece, 18%; and Hungary, 18%. Included patients per country were as follows: 395 from the United States, 165 from Greece, and 125 from Hungary. In the total of 685 included patients with SSM and NM, 437 of 538 (81.0%) had thinner SSM (≤2 mm) and 40 of 147 (27.2%) had thinner NM (≤2 mm) (Figure).

Figure. Flowchart of Patients With Melanoma Included in the Study.

Of 920 patients assessed for eligibility, 685 were included in the study. Participants were consecutive, newly diagnosed, predominantly Caucasian patients 18 years or older with primary invasive melanoma. As the study aimed to explore differences in tumor thickness at diagnosis between nodular melanoma (NM) and superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), only patients with these histopathological subtypes were included. Of 685 patients, 147 were diagnosed with NM, and 538 were diagnosed with SSM.

The mean (SD) age of participants was 55.6 (15.1) years, and 318 of 685 (46%) were female. Sociodemographic variables and nevus count by melanoma thickness are presented in Table 1. In comparison with patients with SSM, patients with NM were older (mean age, 58.79 years vs 54.71 years; P = .004) and more likely to be male (62% vs 51%; P = .02). For thinner vs thick NM, there were no significant associations by age, sex, marital status, education, or location of melanoma. Phenotypic factors such as skin color, number of nevi, and number of atypical nevi were not associated with melanoma thickness.

Table 1. Basic Characteristics by Melanoma Thickness in Patients With NM or SSM .

| Characteristic | Patients With NM (n = 147) | Patients With SSM (n = 538) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor ≤2 mm | Tumor >2 mm | P Value | Tumor ≤2 mm | Tumor >2 mm | P Value | |

| Patients, No. (%) | 40 (27) | 107 (73) | 437 (81) | 101 (19) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58 (15) | 59 (16) | .72 | 53 (14) | 61 (16) | <.001a |

| Sex, No. (%) | .50 | .25 | ||||

| Male | 23 (25) | 68 (75) | 219 (79) | 57 (21) | ||

| Female | 17 (30) | 39 (70) | 218 (83) | 44 (17) | ||

| Marital status, No. (%)b | .09 | .62 | ||||

| Married | 21 (22) | 74 (78) | 316 (82) | 70 (18) | ||

| Widowed/single never-married/divorced or separated | 18 (35) | 33 (65) | 116 (80) | 29 (20) | ||

| Education, No. (%)c | .45 | <.001a | ||||

| Associate’s degree/graduated from college/postgraduate | 23 (30) | 53 (70) | 277 (87) | 42 (13) | ||

| Secondary/high school | 17 (25) | 52 (75) | 156 (73) | 58 (27) | ||

| Skin color, No. (%) | .30 | .82 | ||||

| Very fair/fair | 36 (29) | 89 (71) | 376 (81) | 86 (19) | ||

| Dark/olive/very dark | 4 (18) | 18 (82) | 61 (80) | 15 (20) | ||

| No. of nevi, No. (%) | .22 | .49 | ||||

| 0-20 | 22 (23) | 75 (77) | 270 (81) | 64 (19) | ||

| 20-50 | 12 (38) | 20 (63) | 100 (79) | 26 (21) | ||

| >50 | 6 (33) | 12 (67) | 67 (86) | 11 (14) | ||

| No. of atypical nevi, No. (%) | .70 | .94 | ||||

| 0 | 19 (24) | 61 (76) | 226 (82) | 49 (18) | ||

| 1-5 | 8 (32) | 17 (68) | 97 (84) | 19 (16) | ||

| >6 | 5 (28) | 13 (72) | 66 (83) | 14 (17) | ||

| Histopathologic ulceration, No. (%)d | .002a,e | <.001a,e | ||||

| No | 25 (39) | 39 (61) | 382 (88) | 51 (12) | ||

| Yes | 12 (16) | 65 (84) | 53 (53) | 47 (47) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | ||

| Location of melanoma, No. (%)f | .91 | .05 | ||||

| Head/neck | 8 (29) | 20 (71) | 39 (75) | 13 (25) | ||

| Trunk | 14 (24) | 44 (76) | 199 (84) | 37 (16) | ||

| Upper extremity | 6 (30) | 14 (70) | 81 (86) | 13 (14) | ||

| Lower extremity | 12 (30) | 28 (70) | 110 (81) | 36 (25) | ||

Abbreviations: NM, nodular melanoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

Statistically significant.

Eight missing values.

Seven missing values.

Four missing values.

Fisher exact test.

Eleven missing values.

Clinical and Behavioral Traits Associated With the Detection of Thinner NM

Routine SSE of some (≥1) or all body parts was not associated with thinner NM (odds ratio [OR], 2.39; 95% CI, 0.84-6.80). There were no self-detected clinical changes of the lesion that were associated with the detection of thinner NM, except for patients who reported noticing a change in any of their moles (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.21-5.67) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Patient Skin Self-Examination Practices Associated With Melanoma Thickness in Patients With NM or SSM .

| Variable | Patients With NM (n = 147) | Patients With SSM (n = 538) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Tumor ≤2 mm, OR (95% CI)a | P Value | Patients, No. | Tumor ≤2 mm, OR (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| Who first noticed the lesion that turned out to be melanoma?c | ||||||

| Patient | 92 | 1.19 (0.47-3.02) | .71 | 265 | 0.66 (0.39-1.13) | .13 |

| Medical provider | 20 | 1.77 (0.52-6.01) | .36 | 111 | 2.48 (1.14-5.40) | .02d |

| Spouse/family/friend/other | 35 | 1 [Reference] | 157 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Routine self-examinatione | ||||||

| Examination of some/all skin | 107 | 2.39 (0.84-6.80) | .10 | 400 | 2.61 (1.60-4.25) | <.001d |

| No examination | 34 | 1 [Reference] | 125 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Body areas routinely examined | ||||||

| Areas that are easy to self-examinef | ||||||

| Yes | 106 | 2.42 (0.85-6.90) | .10 | 391 | 2.59 (1.58-4.23) | <.001d |

| No | 34 | 1 [Reference] | 125 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Areas that are difficult to self-examineg | ||||||

| Yes | 79 | 2.61 (0.88-7.72) | .08 | 326 | 2.82 (1.69-4.71) | <.001d |

| No | 34 | 1 [Reference] | 125 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Areas that are very difficult to self-examineh | ||||||

| Yes | 32 | 1.59 (0.44-5.73) | .48 | 157 | 3.28 (1.73-6.21) | <.001d |

| No | 34 | 1 [Reference] | 125 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| If patient noticed changes that turned out to be melanoma, what were those changes? | ||||||

| Change in border | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 0.28 (0.08-1.01) | .05 | 98 | 1.85 (0.92-3.70) | .08 |

| No | 119 | 1 [Reference] | 402 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Different than it used to be | ||||||

| Yes | 65 | 0.78 (0.37-1.66) | .52 | 186 | 0.77 (0.48-1.25) | .30 |

| No | 80 | 1 [Reference] | 314 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Change in thickness/elevation | ||||||

| Yes | 83 | 0.45 (0.21-0.96) | .04d | 148 | 0.20 (0.12-0.34) | <.001d |

| No | 62 | 1 [Reference] | 352 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Onset of pain | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 0.21 (0.05-0.96) | .04d | 35 | 0.28 (0.13-0.61) | .001d |

| No | 123 | 1 [Reference] | 465 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Onset of itching | ||||||

| Yes | 43 | 0.56 (0.23-1.40) | .22 | 103 | 0.50 (0.27-0.82) | .008d |

| No | 102 | 1 [Reference] | 397 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Onset of bleeding | ||||||

| Yes | 43 | 0.42 (0.17-1.06) | .07 | 51 | 0.19 (0.10-0.36) | <.001d |

| No | 102 | 1 [Reference] | 449 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Not applicable or never noticed | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 0.53 (0.11-2.52) | .42 | 80 | 3.51 (1.45-8.46) | .005d |

| No | 199 | 1 [Reference] | 422 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Lesion colori | ||||||

| Pigmented | 97 | 1.16 (0.48-2.85) | .74 | 44 | 1.53 (0.73-3.23) | .26 |

| Don’t know | 13 | 0.23 (0.03-2.12) | .20 | 42 | 4.36 (1.23-15.45) | .02d |

| Pink/skin colored | 33 | 1 [Reference] | 436 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Could patient easily see the lesion?j | ||||||

| Yes | 108 | 2.32 (0.86-6.21) | .10 | 325 | 0.66 (0.40-1.08) | .10 |

| No/don’t know | 37 | 1 [Reference] | 197 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| How often patient carefully examined their molesi | ||||||

| Every 1-2 mo/every 6 mo | 40 | 1.36 (0.60-3.08) | .46 | 153 | 1.49 (0.84-2.62) | .17 |

| Every year | 16 | 0.61 (0.16-2.38) | .48 | 81 | 0.82 (0.43-1.55) | .54 |

| Never | 88 | 1 [Reference] | 295 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Had patient ever noticed a change in any moles?k | ||||||

| Yes | 72 | 2.62 (1.21-5.67) | .02d | 295 | 0.79 (0.50-1.26) | .33 |

| No | 74 | 1 [Reference] | 237 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| When patient first became concerned about the lesionk | ||||||

| Only at time of diagnosis | 37 | 2.07 (0.52-8.31) | .30 | 180 | 1.07 (0.45-2.52) | .89 |

| <4 mo before diagnosis | 62 | 0.77 (0.16-3.71) | .74 | 191 | 0.47 (0.19-1.15) | .10 |

| 4-12 mo before diagnosis | 34 | 1.30 (0.28-5.97) | .73 | 109 | 2.00 (0.81-4.91) | .13 |

| 1+ years before diagnosis | 14 | 1 [Reference] | 51 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Ever used a melanoma picturei | ||||||

| Yes | 23 | 2.48 (0.98-6.30) | .06 | 112 | 1.62 (0.83-3.15) | .16 |

| No | 121 | 1 [Reference] | 417 | 1 [Reference] | ||

Abbreviations: NM, nodular melanoma; OR, odds ratio; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, education.

Twelve missing values.

Statistically significant.

Nineteen missing values.

Included face, front of legs, chest, stomach, and front of arms.

Included neck, upper shoulders, upper back, lower back, back of legs, and back of arms.

Included scalp and bottom of feet.

Seven missing values.

Eighteen missing values.

Twenty missing values.

In the multivariate analysis, receiving a PSE was associated with the detection of thinner NM (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.04-4.69), especially when the physician conducted a whole-body skin examination (OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.05-6.82) rather than examining a particular lesion. For patients with NM, having been told by their doctor that they were at risk for skin cancer was associated with thinner NM detection (OR, 5.32; 95% CI, 2.26-12.53). When PSE was part of the doctor’s routine physical examination, it was not associated with the detection of thinner NM (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 0.81-6.30); it only reached significance when PSE was prompted by increased patient or physician concern or awareness (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Health Care Behaviors Associated With Melanoma Thickness in Patients With NM or SSM .

| Variable | Patients With NM (n = 147) | Patients With SSM (n = 538) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Tumor ≤2 mm, OR (95% CI)a | P Value | Patients, No. | Tumor ≤2 mm, OR (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| Had a usual place to go when sick/needed health advicec | ||||||

| No usual place to go for care | 116 | 1 [Reference] | 65 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Doctor’s office/clinic/health center/urgent care center/emergency department/other | 30 | 1.03 (0.41-2.57) | .95 | 464 | 2.20 (1.15-4.19) | .02d |

| Had a physician for routine caree | ||||||

| No | 54 | 1 [Reference] | 392 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 93 | 1.34 (0.61-2.93) | .47 | 137 | 1.71 (1.01-2.89) | .04d |

| Visits to physician in the year before patient was diagnosed with melanomac | ||||||

| 0 | 22 | 1 [Reference] | 63 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 1 | 38 | 1.42 (0.38-5.32) | .60 | 136 | 0.88 (0.40-1.95) | .76 |

| 2-3 | 44 | 2.70 (0.77-9.45) | .12 | 174 | 1.35 (0.61-3.01) | .46 |

| >3 | 42 | 1.63 (0.44-5.95) | .46 | 156 | 1.51 (0.67-3.41) | .33 |

| Patient received a physician skin examination for cancerf | ||||||

| No/don’t know | 83 | 1 [Reference] | 266 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 59 | 2.21 (1.04-4.69) | .04d | 252 | 1.53 (0.96-2.46) | .08 |

| If patient had a physician examine skin for cancer, what was the reason for examination?f | ||||||

| Part of physician’s routine physical examination | ||||||

| No | 122 | 1 [Reference] | 419 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 19 | 2.26 (0.81-6.30) | .12 | 98 | 1.18 (0.65-2.15) | .58 |

| Physician told patient he or she should be screened for skin cancer | ||||||

| No | 132 | 1 [Reference] | 480 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 9 | 6.27 (1.46-26.88) | .01d | 37 | 1.42 (0.52-3.85) | .49 |

| Patient was concerned about skin cancer | ||||||

| No | 130 | 1 [Reference] | 471 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 11 | 3.86 (1.05-14.23) | .04d | 46 | 0.91 (0.40-2.08) | .82 |

| Patient’s spouse, partner, or other person thought patient should be screened | ||||||

| No | 133 | 1 [Reference] | 485 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 8 | 5.08 (1.13-22.73) | .03d | 32 | 0.89 (0.34-2.31) | .81 |

| Type of skin examination performed by physiciang | ||||||

| None | 86 | 1 [Reference] | 269 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Whole skin | 26 | 2.67 (1.05-6.82) | .04d | 125 | 2.25 (1.16-4.35) | .02d |

| Particular lesion | 28 | 1.73 (0.67-4.49) | .26 | 112 | 1.17 (0.66-2.10) | .59 |

| Don’t know | 2 | 4.23 (0.25-72.67) | .32 | 13 | 0.46 (0.13-1.54) | .21 |

| Did physician tell patient he or she was at risk for skin cancer? | ||||||

| No | 117 | 1 [Reference] | 402 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 30 | 5.32 (2.26-12.53) | <.001d | 127 | 1.98 (1.06-3.71) | .03d |

Abbreviations: NM, nodular melanoma; OR, odds ratio; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, education.

Twelve missing values.

Statistically significant.

Nineteen missing values.

Seven missing values.

Eighteen missing values.

Thinner NM detection was significantly associated with patients taking an interest in reading about skin cancer detection (OR, 4.20; 95% CI, 1.62-10.87), thinking it was important to look at skin for signs of melanoma (OR, 5.52; 95% CI, 2.09-14.50), and believing it was important to have a health care professional examine the skin for signs of melanoma (OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 1.65-10.16) (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Attitudes About Melanoma Associated With Tumor Thickness in Patients With NM or SSM Subtypes.

| Variable | Patients With NM (n = 147) | Patients With SSM (n = 538) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. (With ≤2 mm/>2 mm Tumor, No.) | Tumor ≤2 mm, Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value | Patients, No. (With ≤2 mm/>2 mm Tumor, No.) | Tumor ≤2 mm, Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| Took interest in reading about skin cancer detectionc | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 82 (14/68) | 1 [Reference] | 268 (208/60) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 32 (14/18) | 4.20 (1.62-10.87) | .003d | 125 (109/16) | 1.91 (1.03-3.54) | .04 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 32 (12/20) | 3.28 (1.27-8.47) | .01d | 139 (117/22) | 1.49 (0.86-2.61) | .16 |

| Important to look at skin for signs of melanomae | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 64 (7/57) | 1 [Reference] | 198 (108/32) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 56 (22/34) | 5.52 (2.09-14.58) | .001d | 194 (168/26) | 1.62 (0.93-2.80) | .09 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 26 (11/15) | 6.86 (2.19-21.50) | .001d | 139 (113/26) | 1.26 (0.72-2.20) | .42 |

| Important to have a health care professional examine skin for signs of melanomae | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 60 (8/52) | 1 [Reference] | 140 (108/32) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 66 (25/41) | 4.10 (1.65-10.16) | .002d | 287 (239/48) | 1.47 (0.87-2.51) | .15 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 (7/13) | 3.57 (1.08-11.78) | .04d | 104 (86/18) | 1.52 (0.78-2.96) | .22 |

| Comfortable having a family member look at molesf | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 36 (3/33) | 1 [Reference] | 100 (78/22) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 73 (26/47) | 6.32 (1.75-22.76) | .005d | 297 (248/49) | 1.39 (0.77-2.49) | .28 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 35 (10/25) | 4.70 (1.15-19.11) | .03d | 126 (104/22) | 1.39 (0.70-2.76) | .35 |

| Comfortable undressing for a skin examination by a health care professionalg | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 37 (3/34) | 1 [Reference] | 140 (109/31) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 86 (33/53) | 7.09 (2.01-24.99) | .002d | 308 (255/53) | 1.31 (0.78-2.20) | .30 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 22 (4/18) | 2.57 (0.52-12.80) | .25 | 82 (69/13) | 1.40 (0.67-2.94) | .37 |

| Patient never thought of self at risk for melanomah | ||||||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 25 (10/15) | 1 [Reference] | 126 (113/13) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 107 (20/87) | 0.36 (0.14-0.94) | .04d | 323 (252/71) | 0.53 (0.28-1.02) | .06 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 (10/4) | 4.29 (1.01-18.19) | .048d | 84 (70/14) | 0.61 (0.27-1.40) | .24 |

Abbreviations: NM, nodular melanoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, education.

Twelve missing values.

Statistically significant.

Nineteen missing values.

Seven missing values.

Eighteen missing values.

Twenty missing values.

Patients who were comfortable having a family member look at their moles and were comfortable undressing for a skin examination by a health care professional had an estimated 6-fold to 7-fold increased probability of being diagnosed with thinner NM compared with thick NM. Patients who never thought of themselves at risk for melanoma were at higher risk for thicker NM (Table 4).

Clinical and Behavioral Traits Associated With the Detection of Thinner SSM

Routine SSE of some (≥1) or all body parts was significantly associated with thinner SSM (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.14-5.40). Thinner SSM was associated with the regular SSE of body areas that were easy to self-examine (face, front of legs, chest, stomach, and front of arms) (OR, 2.59; 95% CI, 1.58-4.23), difficult to self-examine (neck, upper shoulders, upper back, lower back, back of legs and arms) (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.69-4.71), or very difficult to self-examine (scalp and bottom of feet) (OR, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.73-6.21). Self-detected clinical warning signs (eg, elevation, onset of pain, itching, and bleeding) were markers of thick SSM (Table 2).

Receiving a whole-body PSE was associated with thinner SSM (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.16-4.35) (Table 3). There were no significant associations of patient attitudes and perceptions about melanoma with thinner SSM (Table 4).

A secondary analysis using a cutoff of 1 mm or less for the definition of thinner SSM showed similar statistically significant results (data not shown).

Mode of Thinner Melanoma Detection According to SSE and PSE Practices

The majority of all patients with NM and SSM (53%) first noticed their melanoma compared with those whose tumors were detected by spouses, partners, family, friends, and others (28%) or a physician (19%). When examining tumor thickness by the person who first noticed the melanoma, patient detection of melanoma was not associated with thinner tumors. However, detection of melanoma by a medical provider was associated with thinner SSM (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.14-5.40) but not with thinner NM (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.52-6.01) (Table 2).

Skin self-examination is successful when it leads to detection of early melanoma. Among the 107 patients with NM who performed SSE, 67 (63%) self-detected their melanoma; however, only 22 (33%) of the patients who self-detected their melanoma were able to self-detect an NM less than or equal to 2 mm in thickness (P = .60). Among the 89 patients who self-detected NM (3 patients had missing data), only 24 (27%) self-detected thinner NM. Among the 24 patients with thinner NM, most performed SSE (n = 22; 92%) compared with those who did not perform SSE (n = 2; 8%) (P = .03). This implies that self-detection of thinner NM was achieved primarily through regular SSE, even though the overall rates of successful SSE for NM were low.

Discussion

For skin cancer screening, PSE and SSE practices are complementary approaches that may reduce melanoma-associated morbidity and mortality.7,21,22 Our study investigated PSE, SSE, and patient attitudes related to the detection of thinner melanoma and explored differences in patients with SSM vs NM. Our pooled analysis of data from expert centers in 3 different countries focused for the first time on NM, the most commonly fatal melanoma subtype. For our primary study outcome, a cutoff of less than or equal to a Breslow thickness of 2 mm was selected for thinner NM, as there were only 4 NM measuring 1 mm or less, precluding any meaningful analysis in this thickness group. This fact highlights the challenge of detecting thin NM, due to their small size, morphology that often does not follow the ABCD (asymmetry, border irregularity, color variation, and diameter >6 mm) criteria, and the higher growth rate and tumor kinetics compared with SSM.12,13,15 Recent survival data published in the new American Joint Committee on Cancer classification demonstrate similar 5-year survival rates for T1 and T2 melanomas, ie, 5-year survival of 99% for T1a melanoma, 99% for T1b, 96% for T2a, and 93% for T2b.23 These findings support our analysis using the 2-mm cutoff for the study of thinner NM and SSM.

Most melanomas were first noticed by the patient in our study, as previously reported24,25,26,27; however, self-detection did not result in significantly thinner NM or SSM, at least in part because of the fact that most patients who self-detected melanoma did not perform regular SSE.

Performing regular SSE was associated with thinner SSM but not thinner NM. Skin self-examination has been associated with the detection of thinner melanoma,9,19,24,25,27 and with reduced melanoma incidence in a population-based case-control study28 in the United States. Although SSE did not result in significant rates of thinner NM detection in our study, those few patients who reported self-detection of thinner NM achieved this through SSE. Performance of SSE does not ensure that patients will be able to self-detect thinner NM, as opposed to thicker NM that may exhibit more obvious detectable changes, such as bleeding, ulceration, and elevation.29,30 In this study, no self-recognized clinical changes of the lesion were associated with the detection of thinner NM, with the exception of patients who noticed a change in any of their moles, affirming the value of educating patients and providers regarding the outlier phenomenon and the need to seek prompt medical attention for a changing lesion. Both the “ugly duckling” rule and the addition of E (for evolving) have provided important clinical warning signs to improve the recognition of NM.31,32,33,34,35 Our findings support the importance of educating individuals on SSE practices, including thoroughness and frequency,19,36 and highlight the need for complementary practices such as PSE for the detection of thinner NM.

Physician detection of melanoma is associated with detection of thinner melanoma.24,26 Whole-body PSE in the year before melanoma diagnosis was associated with a 2.5-fold increased probability of thin melanoma detection in US patients.8 A population-based, case-control study in Australia reported that whole-body PSE was associated with a 38% higher probability of being diagnosed with a thin melanoma (≤0.75 mm).37 A risk-stratified approach to skin cancer screening with whole-body examination by a dermatologist, supported by total-body photography and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging, was effective for the early detection of melanoma in a prospective 5-year study.38,39 Notably, in our study, whole-body PSE was associated with more than a 2-fold increased likelihood of detection of thinner tumors for both SSM and NM, while the examination of only a particular lesion was not. Physician examination may have an indirect effect on thinner melanoma detection by increasing overall patient awareness rather than focusing on a specific suspicious lesion. Training of physicians focusing on whole-body PSE for skin cancer, possibly with the assistance of dermoscopy, smart phone applications, or even artificial intelligence, may enhance thinner NM detection.40

Behavioral and attitudinal predispositions and intentions to perform a practice (such as receipt of screening) may be strong indicators of one’s actual practice. In our study, patients diagnosed with thinner NM were more likely than patients with thick NM to read about skin cancer, express the importance of looking at the skin for signs of melanoma, and have a health care professional examine the skin, suggesting that awareness can be a behavioral driver for earlier discovery of NM.

Limitations

Study limitations include possible reporting and recall bias of the frequency or completeness of SSE and PSE practices in the year prior to diagnosis. The statistically significant differences in awareness in patients with thinner NM had very wide confidence intervals because few patients had thinner NM across categories, and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Also, a relatively small number of thinner NM were included; other studies of NM have also been hampered by small sample sizes, emphasizing the need for expanded investigation of larger cohorts with more thin and thick NM.

Conclusions

Our pooled analysis shows that receipt of a whole-body PSE in the year before diagnosis was associated with diagnosis of thinner NM, while recognition of clinical changes in the lesion was not. Routine SSE was associated with the detection of thinner SSM but not thinner NM, although significantly more patients who performed SSE succeeded in self-detection of thinner NM than those who did not perform SSE. These findings underscore the challenges of early NM detection and highlight the importance of complementary practices that include regular whole-body PSE and increased patient and family awareness and education about SSE and PSE practices to promote earlier detection of NM and SSM.

References

- 1.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. . Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green AC, Baade P, Coory M, Aitken JF, Smithers M. Population-based 20-year survival among people diagnosed with thin melanomas in Queensland, Australia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1462-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(6):1161-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baade P, Meng X, Youlden D, Aitken J, Youl P. Time trends and latitudinal differences in melanoma thickness distribution in Australia, 1990-2006. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(1):170-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geller AC, Clapp RW, Sober AJ, et al. . Melanoma epidemic: an analysis of six decades of data from the Connecticut Tumor Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4172-4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minini R, Rohrmann S, Braun R, Korol D, Dehler S. Incidence trends and clinical-pathological characteristics of invasive cutaneous melanoma from 1980 to 2010 in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(2):145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunssen A, Waldmann A, Eisemann N, Katalinic A. Impact of skin cancer screening and secondary prevention campaigns on skin cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(1):129-139.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swetter SM, Pollitt RA, Johnson TM, Brooks DR, Geller AC. Behavioral determinants of successful early melanoma detection: role of self and physician skin examination. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3725-3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talaganis JA, Biello K, Plaka M, et al. . Demographic, behavioural and physician-related determinants of early melanoma detection in a low-incidence population. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(4):832-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balch CM, Balch GC, Sharma RR. Identifying early melanomas at higher risk for metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1406-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain AJ, Fritschi L, Giles GG, Dowling JP, Kelly JW. Nodular type and older age as the most significant associations of thick melanoma in Victoria, Australia. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(5):609-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. . Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Dowling JP, Murray WK, et al. . Rate of growth in melanomas: characteristics and associations of rapidly growing melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(12):1551-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geller AC, Elwood M, Swetter SM, et al. . Factors related to the presentation of thin and thick nodular melanoma from a population-based cancer registry in Queensland Australia. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1318-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain AJ, Fritschi L, Kelly JW. Nodular melanoma: patients’ perceptions of presenting features and implications for earlier detection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(5):694-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwald HS, Friedman EB, Osman I. Superficial spreading and nodular melanoma are distinct biological entities: a challenge to the linear progression model. Melanoma Res. 2012;22(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demierre MF, Chung C, Miller DR, Geller AC. Early detection of thick melanomas in the United States: beware of the nodular subtype. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(6):745-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreau JF, Weinstock MA, Geller AC, Winger DG, Ferris LK. Individual and ecological factors associated with early detection of nodular melanoma in the United States. Melanoma Res. 2014;24(2):165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollitt RA, Geller AC, Brooks DR, Johnson TM, Park ER, Swetter SM. Efficacy of skin self-examination practices for early melanoma detection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):3018-3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark WH Jr, From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29(3):705-727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteman DC, Baade PD, Olsen CM. More people die from thin melanomas (≤1 mm) than from thick melanomas (>4 mm) in Queensland, Australia. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):1190-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Kim CC, Swetter SM, et al. ; Melanoma Prevention Working Group—Pigmented Skin Lesion Sub-Committee . Survival is not the only valuable end point in melanoma screening. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(5):1332-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. ; American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform . Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carli P, De Giorgi V, Palli D, et al. ; Italian Multidisciplinary Group on Melanoma . Dermatologist detection and skin self-examination are associated with thinner melanomas: results from a survey of the Italian Multidisciplinary Group on Melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(5):607-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brady MS, Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, et al. . Patterns of detection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89(2):342-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantor J, Kantor DE. Routine dermatologist-performed full-body skin examination and early melanoma detection. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(8):873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, Mofid M, Koch SE. Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? JAMA. 1999;281(7):640-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berwick M, Begg CB, Fine JA, Roush GC, Barnhill RL. Screening for cutaneous melanoma by skin self-examination. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(1):17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Rossari S, et al. . Is skin self-examination for cutaneous melanoma detection still adequate? A retrospective study. Dermatology. 2012;225(1):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richard MA, Grob JJ, Avril MF, et al. . Melanoma and tumor thickness: challenges of early diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(3):269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Kopf AW. Early detection of malignant melanoma: the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin. CA Cancer J Clin. 1985;35(3):130-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rigel DS, Russak J, Friedman R. The evolution of melanoma diagnosis: 25 years beyond the ABCDs. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):301-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldsmith SM, Cognetta AB Jr. Time to move forward after the report of the AAD Task Force for the ABCDEs of Melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):e149-e150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. . Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: revisiting the ABCD criteria. JAMA. 2004;292(22):2771-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, Kopf AW, Polsky D. ABCDE—an evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):1032-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Stapleton JL, Tatum KL, Goydos JS. Skin self-examination behaviors among individuals diagnosed with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016;26(1):71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, Youl P, English D. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):450-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sondak VK, Glass LF, Geller AC. Risk-stratified screening for detection of melanoma. JAMA. 2015;313(6):616-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moloney FJ, Guitera P, Coates E, et al. . Detection of primary melanoma in individuals at extreme high risk: a prospective 5-year follow-up study. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(8):819-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. . Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]