Key Points

Question

Can low doses of hyaluronidase safely and effectively dissolve hyaluronic acid filler nodules?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 9 women and 72 injection sites, small unit doses of hyaluronidase allowed removal of minute quantities of filler without removing the entire implant.

Meaning

Minor asymmetries after filler can be corrected by the injector in a manner convenient for patients.

This parallel-group, randomized clinical trial assesses the effectiveness and dose-related effect of small quantities of hyaluronidase vs saline to treat hyaluronic acid filler nodules in healthy women.

Abstract

Importance

Although hyaluronidase is known to remove hyaluronic acid fillers, use of low doses has not been well studied.

Objective

To assess the effectiveness and dose-related effect of small quantities of hyaluronidase to treat hyaluronic acid filler nodules.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Split-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial at an urban academic center. Participants were 9 healthy women. Recruitment and follow-up occurred from February 2013 to March 2014; data analysis occurred from February to July 2016.

Interventions

Each participant received aliquots (buttons) of either of 2 types of hyaluronic acid fillers into bilateral upper inner arms, respectively. At 1, 2, and 3 weeks each button was treated with a constant volume (0.1 mL) of variable-dose hyaluronidase (1.5, 3.0, or 9.0 U per 0.1 mL) or saline control.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Both a blinded dermatologist and the participant independently assessed detectability.

Results

Seventy-two treatment sites on 9 women (mean [SD] age, 45.8 [15.7] years) received all interventions and were analyzed. There was a significant difference in physician rater assessment between saline and hyaluronidase at 4 weeks (visual detection: mean difference = 1.15; 95% CI, 0.46-1.80; P < .001; palpability: mean difference = 1.22; 95% CI, 0.61-1.83; P < .001) and 4 months (visual detection: mean difference = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.33-1.26; P = .001; palpability: mean difference = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.38-1.25; P < .001) that was mirrored by participant self-assessment at 4 weeks (visual detection: mean difference = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.26-1.48; P = .006; palpability: mean difference = 1.59; 95% CI, 1.41-1.77; P < .001) and 4 months (visual detection: mean difference = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.09-1.53; P < .001; palpability: mean difference = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.03-2.01; P < .001), and hyaluronidase was associated with greater resolution of buttons compared with normal saline. The 9.0-unit hyaluronidase injection sites were significantly less palpable than the 1.5-unit sites at both 4 weeks (mean difference = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.01-.99; P = .045) and 4 months (mean difference = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.14-0.81; P = .007). Dose dependence was more notable for Restylane-L.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although very small doses of hyaluronidase can remove hyaluronic acid fillers from patient skin, slightly higher doses often result in more rapid resolution.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01722916

Introduction

In 2003, the first hyaluronic acid (HA) filler was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat facial wrinkles and folds. This ensured the ascendancy of noninvasive cosmetic dermatology that had already been initiated with the approval of botulinum toxin and selective lasers. One particularly attractive feature of HA hyaluronic fillers is their reversibility in response to injections of hyaluronidase, a naturally occurring enzyme that degrades the product.

Abundant anecdotal literature exists regarding the utility of hyaluronidase for the management of filler complications. Initially, the primary indication for hyaluronidase was correction of asymmetry, or of intravascular injection, commonly into the perinasal or glabellar small vessels.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 More recently, the use of hyaluronidase has been reported in the context of catastrophic outcomes, such as blindness due to unintended retrograde movement of HA to the retina.16,17 Some longer-lasting HA fillers are reported to be partially resistant to hyaluronidase, and persistent delayed nodules associated with use of such HA fillers are typically corrected with repeated high-dose injections of hyaluronidase.18,19

Overall, most of the literature on hyaluronidase use for HA fillers focuses on relatively high-dose injections to reverse complications of HA filler use. The 1 existing clinical trial reports on the use of medium to high doses, and found no significant dose dependence in the rate of resolution.20

There have, however, been sporadic reports about the utility of very small doses of hyaluronidase in correcting HA injection asymmetry, especially around the eye.21 Given the ubiquitous use of HA fillers, and the expense and time required to inject them, correction of minor asymmetries appears a worthwhile objective that may benefit many patients. Such injections may reduce patient dissatisfaction with suboptimal results and also with the additional cost incurred when undesired filler-associated contours are fully dissolved with hyaluronidase followed by reinjection of HA filler.

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness and dose-related effect, if any, of graded small doses of hyaluronidase for removal of injected HA filler. The 2 most commonly used HA fillers in the United States were studied.

Methods

Trial Design

This was a split-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial based at a single urban academic center, with a 1:1 allocation ratio and a block size of 2 for allocation to HA filler type. Once HA filler type was assigned, there was 1:1:1:1 allocation to 1 of 3 microconcentrations of hyaluronidase (plus 1 control arm), with a block size of 4. The unit of randomization was the individual unilateral button of hyaluronidase. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. Written consent was obtained from all participants before study procedures began. The trial protocol is available in the Supplement.

Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of healthy women who were not pregnant or lactating. Other exclusion criteria included use of isotretinoin within the past 6 months, history of hypertrophic or keloidal scarring, tattoos or scars in the treatment areas of the upper medial arms, and known sensitivity to HA. Procedures were performed and data were collected at the outpatient dermatology clinic of the Northwestern Medical Group in downtown Chicago, Illinois.

Interventions

Placement of Hyaluronic Acid Filler Buttons

Each participant had 8 treatment sites along their bilateral upper inner (medial) arms, 4 on each arm, with sites 5 cm apart and marked with ink spots from a surgical pen. For each participant, each arm received either of 2 types of HA filler (Juvéderm Ultra XC, Allergan Inc; or Restylane-L, Galderma Laboratories). Each arm was then injected with 4 separate aliquots of the assigned HA filler (volume of 0.4 mL each) placed 1.5 cm medial to each of the 4 marked sites. Placed at the dermal-subcutaneous junction, each aliquot was approximately round and button shaped, delivered from a single point of insertion using the standard syringe apparatus with a fresh 30-gauge needle.

Hyaluronidase Injections

At each visit 1, 2, and 3 weeks after HA filler placement, hyaluronidase (Vitrase, Alliance Medical Products, Inc) or control normal saline was injected into each of the 4 HA filler aliquot sites on each arm. Through separate 1-mL Luer-Lok syringes with 30-gauge needles, exactly 1 button on each arm received 0.1 mL of each of the 4 investigational products: (1) 1.5 U/0.1 mL hyaluronidase, (2) 3.0 U/0.1 mL, (3) 9.0 U/0.1 mL, or (4) 0.1 mL normal saline control. Once a button was assigned to a particular treatment arm, the button was injected with the same concentration of investigational products at each treatment visit 1, 2, and 3 weeks after HA filler placement. To avoid imprecise injection due to needle hub dead space, total syringe volume was greater than the amount required and decreased by 0.1 mL with each injection, and the remainder discarded. The different concentrations were achieved using normal saline to dilute fresh vials of stock hyaluronidase (200 U per 1.2 mL) at each visit. Participants returned for follow-up 1 week after the third and final hyaluronidase injection session, and then for final follow-up 3 months later. At the final (4-month) visit, if any previous HA filler injection sites remained detectable, hyaluronidase was injected again sufficient to dissolve the remaining filler.

Ratings and Data Collection

Before the hyaluronidase injections at each visit, as well as at 4-week and 4-month follow-up visits, a blinded dermatologist (K.P.) rated the detectability of each button on a 5-point scale based on “visual detection” and “palpability.” Participants also independently self-reported detectability of buttons.

Outcomes

Primary Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the dose of hyaluronidase that rendered the individual button no longer detectable to a blinded dermatologist rater based on the following 2 measures: (1) visual detection, defined as deviation from smoothness or visible bulge when examining the button from the side, both with and without side lighting and with and without 3× to 5× magnification with a handheld magnifier; and (2) palpability, defined as detection of a papule, nodule, or other skin mass (not related to normal skin or underlying normal skin structure) with increasing pressure from light touch to firm pressure while moving the fingerpad tip of the dominant index finger across the site of the placement of the button. Detectability was rated on a 5-point scale as follows: 0 = undetectable, 1 = faintly perceptible, 2 = mildly perceptible, 3 = moderately perceptible, 4 = very perceptible.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Secondary outcome measures included the same statistics computed based on patient self-report of detectability. The occurrence and extent of any adverse events during the duration of the study were noted as well. Adverse event reports were actively elicited by investigators at each study visit from baseline to end of study.

Sample Size Determination

For 10 buttons injected with 9.0 U hyaluronidase each, we can expect mean detectability to decrease from 4.0 (very perceptible) to 0; for buttons injected with 3.0 U, mean detectability after first injection can be expected to be 1.0 to 1.5; and for buttons injected with 1.5 U, mean detectability is expected to be 2.0 to 2.5. With 10 buttons per each treatment and placebo, and α level of .05, there was 99%, 98%, and 88% power to find expected differences between each dosage level and normal saline control, respectively, as well as 98% and 88% power to find a significant dose effect.

Randomization

Participant screening and enrollment were performed by 2 researchers (R.H. and A.G.). Random sequence generation and concealment were performed (by E.P.) and conducted using a computer-based random number generator, with the outcomes recorded on individual paper cards that were then placed in sealed, opaque, consecutively numbered envelopes. Randomization with block size of 2 was used to assign each participant’s arm to 1 of 2 filler types (0, 1); then randomization with block size of 4 (0, 1, 2, 3) was used to assign each button on each arm to a treatment or control hyaluronidase concentration. Study assignments were overseen by E.P. Study treatments were delivered by 2 dermatologists (M.A. and K.P.).

Blinding

The rater assessing the filler buttons for detectability was blinded to the assignment and to type of filler, as well as to injection of hyaluronidase or control solutions. Participants rating filler buttons were similarly blinded to assignments. Injectors placing filler and injectors subsequently delivering hyaluronidase solution were also blinded as to the type of filler or solution, respectively, that they were injecting. Both fillers were translucent and of approximately similar viscosity, filler names and syringe markings were concealed by tape at injection, and injections were univolemic and placed at similar depth in the skin with the same caliber needles. All injections of hyaluronidase or control solution were clear, aqueous, isovolemic, delivered via identical syringes and needles, and otherwise indistinguishable to the injectors and the participants.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed on deidentified data. The units required for elimination of detectability were compared for the 3 concentrations of hyaluronidase used. Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed on 4 preplanned comparisons at each study visit. Subgroup analysis was used to investigate any differences associated with the type of HA preparation.

Results

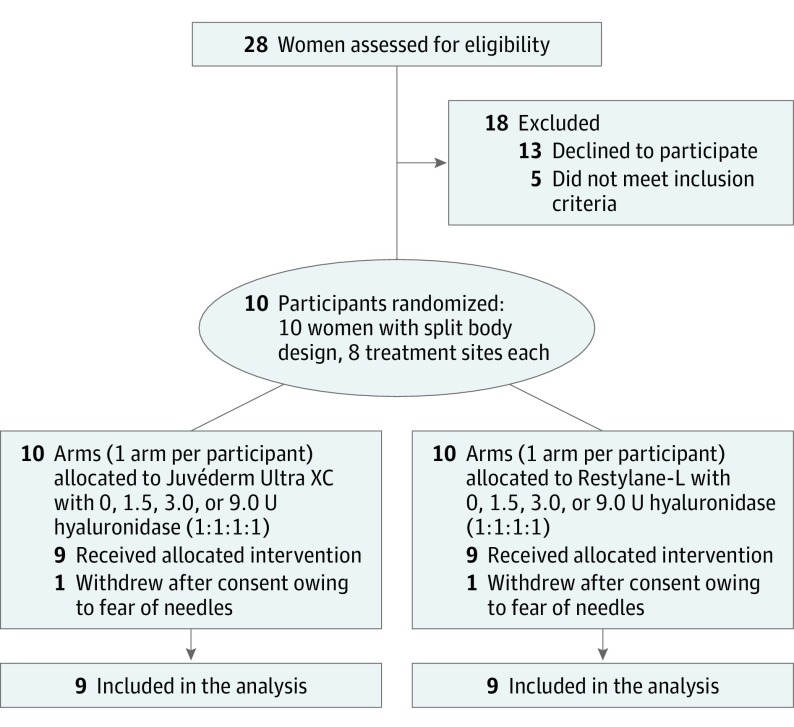

Recruitment and follow-up occurred during the period from February 2013 to March 2014. A total of 72 sites, all on 9 women (7 white and 2 black), were randomized, treated, received all interventions, and were analyzed (Figure 1). One participant withdrew from the study before intervention because of needle phobia. No adverse events were observed or reported.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flowchart.

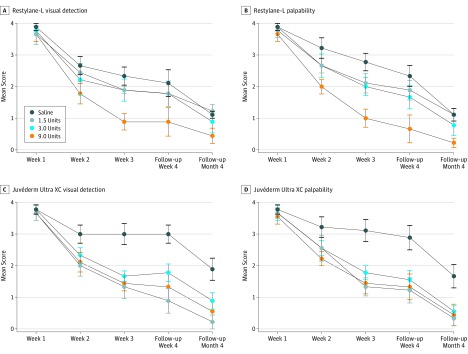

Mean blinded rater and participant self-report scores for buttons of each filler evaluated by each method (ie, visual inspection and palpation) are provided in Table 1. Pairwise comparisons of scores are presented in Table 2. Means and SE are displayed graphically in Figure 2 for physician rater measures and Figure 3 for participant-reported measures.

Table 1. Dermatologist and Patient Ratings of Mean Detectability of Hyaluronic Acid Filler Buttonsa.

| Hyaluronidase Dose | Detectability,b Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Week 1) |

Week 2 | Week 3 | Follow-up (Week 4) |

Follow-up (Month 4) | |

| Dermatologists | |||||

| Visual detection | |||||

| Restylane-L | |||||

| Saline | 3.89 (0.33) | 2.67 (0.87) | 2.33 (0.87) | 2.11 (1.27) | 1.11 (0.33) |

| 1.5 U | 3.67 (1.00) | 2.44 (0.88) | 1.89 (0.33) | 1.78 (1.20) | 1.22 (0.67) |

| 3.0 U | 3.78 (0.44) | 2.22 (1.39) | 1.89 (1.05) | 1.78 (1.20) | 0.89 (1.05) |

| 9.0 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 1.78 (0.97) | 0.89 (0.78) | 0.89 (1.36) | 0.44 (0.73) |

| Juvéderm Ultra XC | |||||

| Saline | 3.78 (0.44) | 3.00 (0.87) | 3.00 (1.00) | 3.00 (0.87) | 1.89 (1.05) |

| 1.5 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 2.00 (1.00) | 1.33 (1.12) | 0.89 (1.17) | 0.22 (0.67) |

| 3.0 U | 3.78 (0.44) | 2.33 (0.71) | 1.67 (0.50) | 1.78 (0.83) | 0.89 (0.78) |

| 9.0 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 2.11 (0.93) | 1.44 (0.73) | 1.33 (1.41) | 0.56 (1.01) |

| Palpability | |||||

| Restylane-L | |||||

| Saline | 3.89 (0.33) | 3.22 (0.97) | 2.78 (0.83) | 2.33 (1.00) | 1.11 (0.60) |

| 1.5 U | 3.78 (0.67) | 2.67 (0.71) | 2.11 (0.93) | 1.89 (0.930 | 1.11 (0.60) |

| 3.0 U | 3.89 (0.33) | 2.67 (1.12) | 2.00 (0.87) | 1.67 (1.12) | 0.78 (0.97) |

| 9.0 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 2.00 (0.71) | 1.00 (0.87) | 0.67 (1.32) | 0.22 (0.44) |

| Juvéderm Ultra XC | |||||

| Saline | 3.78 (0.44) | 3.22 (0.97) | 3.11 (1.05) | 2.89 (1.17) | 1.67 (1.12) |

| 1.5 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 2.56 (1.24) | 1.33 (0.87) | 1.22 (1.20) | 0.33 (0.71) |

| 3.0 U | 3.67 (0.50) | 2.56 (0.73) | 1.78 (0.67) | 1.56 (0.88) | 0.56 (0.53) |

| 9.0 U | 3.56 (0.73) | 2.22 (0.67) | 1.44 (1.01) | 1.33 (1.22) | 0.44 (1.01) |

| Patients | |||||

| Visual detection | |||||

| Restylane-L | |||||

| Saline | 3.44 (0.88) | 2.78 (1.39) | 2.56 (1.13) | 2.22 (1.20) | 1.89 (0.93) |

| 1.5 U | 3.67 (0.50) | 2.11 (0.93) | 2.00 (0.71) | 1.89 (0.93) | 1.56 (1.13) |

| 3.0 U | 3.44 (0.73) | 2.11 (1.05) | 2.00 (0.71) | 1.78 (0.97) | 1.11 (0.93) |

| 9.0 U | 3.44 (0.73) | 1.67 (1.00) | 1.44 (1.33) | 1.44 (1.42) | 0.56 (0.88) |

| Juvéderm Ultra XC | |||||

| Saline | 3.22 (0.97) | 2.67 (1.12) | 2.67 (1.00) | 2.44 (1.59) | 2.44 (1.24) |

| 1.5 U | 3.00 (1.12) | 1.44 (1.01) | 1.44 (1.01) | 1.22 (1.09) | 0.44 (0.73) |

| 3.0 U | 3.22 (0.83) | 2.00 (0.87) | 1.78 (1.09) | 1.22 (0.97) | 1.11 (1.36) |

| 9.0 U | 3.44 (0.73) | 1.44 (0.73) | 1.56 (1.01) | 1.22 (0.83) | 0.33 (0.50) |

| Palpability | |||||

| Restylane-L | |||||

| Saline | 3.33 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.00) | 2.67 (1.22) | 2.33 (1.22) | 2.00 (1.12) |

| 1.5 U | 3.67 (0.71) | 2.11 (0.78) | 1.56 (0.73) | 1.11 (0.78) | 1.11 (0.78) |

| 3.0 U | 3.56 (0.73) | 2.22 (1.09) | 1.44 (1.01) | 1.56 (1.13) | 0.67 (0.87) |

| 9.0 U | 3.22 (1.09) | 1.67 (0.71) | 0.78 (1.39) | 0.78 (0.97) | 0.22 (0.67) |

| Juvéderm Ultra XC | |||||

| Saline | 3.11 (1.17) | 3.33 (0.87) | 2.89 (1.17) | 2.78 (1.30) | 2.22 (0.97) |

| 1.5 U | 2.89 (1.36) | 2.33 (1.22) | 1.11 (0.78) | 0.89 (0.93) | 0.44 (0.73) |

| 3.0 U | 3.00 (1.12) | 2.00 (1.12) | 2.00 (1.32) | 1.11 (1.05) | 0.89 (1.27) |

| 9.0 U | 3.11 (0.93) | 1.89 (1.45) | 1.11 (0.93) | 0.33 (0.50) | 0.22 (0.44) |

Juvéderm Ultra XC, Allergan Inc; or Restylane-L, Galderma Laboratories.

Detectability was rated on a 5-point scale as follows: 0 = undetectable, 1 = faintly perceptible, 2 = mildly perceptible, 3 = moderately perceptible, 4 = very perceptible.

Table 2. Dermatologist and Patient Pairwise Comparisons at 4 Weeks and 4 Months.

| Comparisons of Hyaluronidase Doses | 4 Weeks | 4 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference (95% CI) | P Value | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Saline vs all hyaluronidase | ||||

| Physician | ||||

| Visual detection | 1.15 (0.46-1.80) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.33-1.26) | .001 |

| Palpability | 1.22 (0.61-1.83) | <.001 | 0.82 (0.38-1.25) | <.001 |

| Patient | ||||

| Visual detection | 0.87 (0.26-1.48) | .006 | 1.31 (1.09-1.53) | <.001 |

| Palpability | 1.59 (1.41-1.77) | <.001 | 1.52 (1.03-2.01) | <.001 |

| Physician and patient combined | ||||

| Visual detection | 1.00 (0.57-1.45) | <.001 | 1.05 (0.96-1.42) | <.001 |

| Palpability | 1.40 (0.99-1.82) | <.001 | 1.17 (0.84-1.50) | <.001 |

| 1.5 vs 9.0 U | ||||

| Physician and patient combined | ||||

| Visual detection | 0.22 (0.34-0.78) | .43 | 0.39 (0.02-0.80) | .06 |

| Palpability | 0.50 (0.01-0.99) | .045 | 0.47 (0.14-0.81) | .007 |

Figure 2. Dermatologist Ratings for Perceptibility of Hyaluronic Acid Filler Buttons.

A, Restylane-L (Galderma Laboratories), normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at all follow-up visits; 1.5 vs 9.0 U, significant difference at week 3. B, Restylane-L, normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at all follow-up visits; 1.5 vs 9.0 U, significant difference at all follow-up visits; 3.0 vs 9.0 U, significant difference at week 4. C, Juvéderm Ultra XC (Allergan Inc), normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at weeks 2, 3, and 4; normal saline vs 1.5 U, significant difference at weeks 2, 3, and 4; normal saline vs 3.0 U, significant difference at weeks 3 and 4. D, Juvéderm Ultra XC, normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at weeks 3, 4, and month 4; normal saline vs 1.5 U, significant difference at weeks 3 and 4; normal saline vs 3.0 U, significant difference at weeks 3 and 4; 1.5 U vs 9.0 U, significant difference at month 4. Data markers indicate dose of hyaluronidase, and error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Differences were statistically significant at P < .05.

Figure 3. Participant Ratings for Perceptibility of Hyaluronic Acid Filler Buttons.

A, Restylane-L (Galderma Laboratories), normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at month 4. B, Restylane-L, normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at all follow-up visits; normal saline vs 1.5 U, significant difference at weeks 3 and 4; normal saline vs 3 U, significant difference at weeks 2, 3, and month 4. C, Juvéderm Ultra XC (Allergan Inc), normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at weeks 2, 4, and month 4; normal saline vs 1.5 U, significant difference at weeks 2, 4, and month 4; normal saline vs 3.0 U, significant difference at week 3 and month 4. D, Juvéderm Ultra XC, normal saline vs 9.0 U, significant rater difference at all follow-up visits; normal saline vs 1.5 U, significant difference at all follow-up visits; normal saline vs 3.0 U, significant difference at all follow-up visits. Data markers indicate dose of hyaluronidase, and error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Differences were statistically significant at P < .05.

There was a statistically significant difference in physician rater assessment between normal saline control and hyaluronidase at 4 weeks (visual detection: mean difference = 1.15; 95% CI, 0.46-1.80; P < .001; palpability: mean difference = 1.22; 95% CI, 0.61-1.83; P < .001) and 4 months (visual detection: mean difference = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.33-1.26; P = .001; palpability: mean difference = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.38-1.25; P < .001), and this was also mirrored in participant self-assessment at 4 weeks (visual detection: mean difference = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.26-1.48; P = .006; palpability: mean difference = 1.59; 95% CI, 1.41-1.77; P < .001) and 4 months (visual detection: mean difference = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.09-1.53; P < .001; palpability: mean difference = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.03-2.01; P < .001), and with hyaluronidase associated with greater resolution of buttons (Table 2). The 9.0-unit hyaluronidase injections were less palpable than the 1.5-unit injections at both 4 weeks (mean difference = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.01-.99; P = .045) and 4 months (mean difference = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.14-0.81; P = .007) (Table 2), with this difference more notable for Restylane-L than for Juvéderm Ultra XC (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Dose dependence was more notable for Restylane-L than for Juvéderm Ultra XC. All filler buttons at all sites were also decreased in terms of visual detection and palpation over time.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a randomized clinical trial that used dosing of hyaluronidase to remove HA. Hyaluronic acid filler aliquots placed in the skin were found to be removed more rapidly with very low doses of injections of hyaluronidase solution than with normal saline control. Moreover, it was shown that minor gradations in dosing, as little as 1 to several units per dose, resulted in differential rates of dissolution, with the filler sites treated with higher doses disappearing more rapidly. This dose-related difference was greater for Restylane-L than for Juvéderm Ultra XC. Importantly, participants and blinded raters, both of whom were blinded regarding filler assignment as well as hyaluronidase concentration, provided consistently similar data.

The clinical relevance of these findings is clear. Minor filler-associated asymmetries, nodules, and textural abnormalities may be corrected safely and effectively with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase. Rather than dissolving all the offending filler, waiting, and then reinjecting fresh filler weeks or months later, dermatologists may precisely sculpt already injected excess filler by titration with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase to the desired skin contour. To maximize precision and minimize error or overcorrection, low-volume, low-dose injections can be repeated weekly until the problem is resolved, and such doses can be slightly varied to treat asymmetries and nodules of differing sizes. This may be especially helpful for correcting minor irregularities in the periocular region.

Precisely removing small areas of excess HA filler is at variance with current common practice, in which areas of concern are typically excessively loaded with hyaluronidase, often resulting in complete removal. This routine use of high-dose hyaluronidase may, in part, derive from the packaging of hyaluronidase, which is provided in vials of hundreds of units per milliliter. Use of the highly concentrated form of the enzyme is certainly appropriate for rapid reversal of HA in emergency situations (eg, cases of suspected vascular occlusion threatening blindness); however, it is excessively potent for the intended use of perfecting cosmetic results and can result in greater than intended localized volume loss. The present study demonstrates that small-volume injection of very low doses of saline-diluted hyaluronidase (1.5-9.0 U per 0.1 mL) is sufficient to decrease the volume of HA buttons and imparts greater control over the degree of volume loss achieved.

Of note, every one of the subdermal filler nodules assessed in this study became less noticeable over time. Even the sites injected with normal saline were associated with time-associated decrease in visibility and palpability. There are at least 3 explanations for these findings. First, any fluid injection, even normal saline, may have broken up a button of filler by mechanical means unrelated to enzymatic activity, thus flattening it and making it less palpable. Second, normal body movement may have resulted in settling and flattening of filler buttons. Finally, temporary fillers are expected to be biodegraded over time, and filler may conceivably be at least partially resorbed over the several weeks’ duration of the study.

The greater dose-related effect seen with Restylane-L than with Juvéderm Ultra XC in the present study is in keeping with what has been demonstrated in prior in vitro studies22,23 and is explained by differences in the biologic properties between the 2 HA fillers. Unlike Juvéderm Ultra XC, a smooth gel filler, Restylane-L is made up of distinct particles, which allows for greater access by hyaluronidase and increased exposure of the HA substrate to its enzymatic activity.22 Juvéderm Ultra XC is also made up of more concentrated and more highly cross-linked HA content.23 Clinically, this means that a greater dose of hyaluronidase is needed to reverse Juvéderm Ultra XC than Restylane-L. Our study provides clinical support for the rule of thumb proposed by Jones et al23 that for each 0.1 mL of Juvéderm Ultra XC HA to be eradicated in vivo, the clinician should begin with 10 U of hyaluronidase.

The present study extends the work from an earlier clinical trial showing that hyaluronidase dissolves HA filler more effectively than normal saline. Vartanian and colleagues20 evaluated injections of 75, 30, 20, and 10 U of hyaluronidase, respectively, and found no significant association for dose with rate of dissolution. In the present study, all doses were smaller than the lowest dose reported by Vartanian et al,20 and likely for this reason, a dose-related effect was detectable. The present study also differed from the earlier study by using 0.4-mL total aliquots of HA filler vs those of 0.2 mL each, with the greater volume likely enhancing the ability to detect small incremental decreases in volume of HA filler. Importantly, we studied both HA filler materials, Restylane-L and Juvéderm Ultra XC, under randomized, controlled conditions.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the fact that the results may not be exactly the same for other forms of commercially available hyaluronidase. As has been reported by others, several varieties are currently on the market and minor differences may exist. That being said, these differences have been found to be modest24,25 and not to substantially affect outcomes with alternative formulations, which can be used almost interchangeably. Another limitation is that we studied filler dissolution primarily in white women. It is possible that men and patients of other races may respond differently, although there is no reason to suppose this to be true. The likely principal determinants of filler nodule resistance to enzymatic dissolution are filler quantity and the location within the skin. Finally, longer-lasting HA fillers (eg, Juvéderm Voluma, Volbella, Volift) may be relatively resistant to hyaluronidase and larger doses may be required to achieve similar results.

Conclusions

Hyaluronidase at low doses was effective for dissolving small intracutaneous nodules of HA filler. There was a graded response, with higher concentrations of hyaluronidase causing more rapid dissolution. These findings offer clinicians a means to modify and fine-tune filler-associated skin contour without resorting to high-dose injections that completely remove all filler from the treatment site.

Trial Protocol

References

- 1.Khan TT, Woodward JA. Retained dermal filler in the upper eyelid masquerading as periorbital edema. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(10):1182-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. . Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler-induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(7):844-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rzany B, Becker-Wegerich P, Bachmann F, Erdmann R, Wollina U. Hyaluronidase in the correction of hyaluronic acid-based fillers: a review and a recommendation for use. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(4):317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sclafani AP, Fagien S. Treatment of injectable soft tissue filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(suppl 2):1672-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox SE. Clinical experience with filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(suppl 2):1661-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narins RS, Coleman WP III, Glogau RG. Recommendations and treatment options for nodules and other filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(suppl 2):1667-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunebaum LD, Bogdan Allemann I, Dayan S, Mandy S, Baumann L. The risk of alar necrosis associated with dermal filler injection. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(suppl 2):1635-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLorenzi C. Transarterial degradation of hyaluronic acid filler by hyaluronidase. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(8):832-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayan SH, Arkins JP, Mathison CC. Management of impending necrosis associated with soft tissue filler injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(9):1007-1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dayan SH, Arkins JP, Somenek M. Restylane persisting in lower eyelids for 5 years. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11(3):237-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire LK, Hale EK, Godwin LS. Post-filler vascular occlusion: a cautionary tale and emphasis for early intervention. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(10):1181-1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park KY, Son IP, Li K, Seo SJ, Hong CK. Reticulated erythema after nasolabial fold injection with hyaluronic acid: the importance of immediate attention. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(11):1697-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee A, Grummer SE, Kriegel D, Marmur E. Hyaluronidase. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(7):1071-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch RJ, Brody HJ, Carruthers JD. Hyaluronidase in the office: a necessity for every dermasurgeon that injects hyaluronic acid. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9(3):182-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaich AS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Injection necrosis of the glabella: protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(2):276-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carruthers J, Fagien S, Dolman P. Retro or peribulbar injection techniques to reverse visual loss after filler injections. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S354-S357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman GJ, Clague MD. A rethink on hyaluronidase injection, intraarterial injection, and blindness: is there another option for treatment of retinal artery embolism caused by intraarterial injection of hyaluronic acid? Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(4):547-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Carruthers A, Mummert ME, Humphrey S. Delayed-onset nodules secondary to a smooth cohesive 20 mg/mL hyaluronic acid filler: cause and management. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(8):929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S, Park KY, Yeo IK, et al. . Investigation of the degradation-retarding effect caused by the low swelling capacity of a novel hyaluronic acid filler developed by solid-phase crosslinking technology. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):357-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vartanian AJ, Frankel AS, Rubin MG. Injected hyaluronidase reduces Restylane-mediated cutaneous augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7(4):231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon H, Thomas M, D’silva J. Low dose of hyaluronidase to treat over correction by HA filler—a case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(4):e416-e417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sall I, Ferard G. Comparison of the sensitivity of 11 crosslinked hyaluronic acid gels to bovine testis hyaluronidase. Polym Degrad Stab. 2007;92:915-919. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones D, Tezel A, Borrel M. In vitro resistance to degradation of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers by ovine testicular hyaluronidase. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:804-809. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landau M. Hyaluronidase caveats in treating filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S347-S353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flynn TC, Thompson DH, Hyun SH. Molecular weight analyses and enzymatic degradation profiles of the soft-tissue fillers Belotero Balance, Restylane, and Juvéderm Ultra. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(4)(suppl 2):22S-32S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol