This randomized clinical trial investigates if early initiation of care goals conversations by a palliative care–trained social worker would improve prognostic understanding, elicit advanced care preferences, and influence care plans for high-risk patients discharged after hospitalization for heart failure.

Key Points

Question

Can routine initiation of goals of care discussions by a palliative care social worker bridging inpatient to outpatient care facilitate greater patient-physician engagement around palliative care considerations in high-risk patients hospitalized with decompensated heart failure?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial, compared with usual care, patients allocated to the social worker–led intervention were more likely to have physician-level documentation of care preferences in the electronic health record and to have prognostic expectations aligned with their physicians without worsening of depression, anxiety, or quality-of-life scores.

Meaning

Training and empowering social workers to initiate goals of care conversations for individuals in inpatient care transitioning to outpatient care may improve the overall quality of care for patients with advanced heart failure.

Abstract

Importance

Palliative care considerations are typically introduced late in the disease trajectory of patients with advanced heart failure (HF), and access to specialty-level palliative care may be limited.

Objective

To determine if early initiation of goals of care conversations by a palliative care–trained social worker would improve prognostic understanding, elicit advanced care preferences, and influence care plans for high-risk patients discharged after HF hospitalization.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective, randomized clinical trial of a social worker–led palliative care intervention vs usual care analyzed patients recently hospitalized for management of acute HF who had risk factors for poor prognosis. Analyses were conducted by intention to treat.

Interventions

Key components of the social worker–led intervention included a structured evaluation of prognostic understanding, end-of-life preferences, symptom burden, and quality of life with routine review by a palliative care physician; communication of this information to treating clinicians; and longitudinal follow-up in the ambulatory setting.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percentage of patients with physician-level documentation of advanced care preferences and the degree of alignment between patient and cardiologist expectations of prognosis at 6 months.

Results

The study population (N = 50) had a mean (SD) age of 72 (11) years and had a mean (SD) left ventricular ejection fraction of 0.33 (13). Of 50 patients, 41 (82%) had been hospitalized more than once for HF management within 12 months of enrollment. At enrollment, treating physicians anticipated death within a year for 32 patients (64%), but 42 patients (84%) predicted their life expectancy to be longer than 5 years. At 6 months, more patients in the intervention group than in the control group had physician-level documentation of advanced care preferences in the electronic health record (17 [65%] vs 8 [33%]; χ2 = 5.1; P = .02). Surviving patients allocated to intervention were also more likely to revise their baseline prognostic assessment in a direction consistent with the physician’s assessment (15 [94%] vs 4 [26%]; χ2 = 14.7; P < .001). Among the 31 survivors at 6 months, there was no measured difference between groups in depression, anxiety, or quality-of-life scores.

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients at high risk for mortality from HF frequently overestimate their life expectancy. Without an adverse impact on quality of life, prognostic understanding and patient-physician communication regarding goals of care may be enhanced by a focused, social worker–led palliative care intervention that begins in the hospital and continues in the outpatient setting.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02805712.

Introduction

Although patients with advanced heart failure (HF) experience high rates of mortality and functional decline, palliative care considerations are often overlooked or introduced late in the disease process.1,2 Heart failure treatment guidelines now encourage discussion of advanced care preferences,3,4 but many hospitals and most outpatient clinics lack the dedicated palliative care personnel necessary to achieve this goal. We hypothesized that routine initiation of goals of care conversations by a palliative care–trained social worker in high-risk patients with HF would facilitate documentation of care preferences and better alignment of patient and physician prognostic expectations.

Methods

We conducted a single-center, prospective, randomized pilot study comparing the impact of a longitudinal, social worker–led palliative care intervention with usual care on advanced care planning and quality of life in patients with HF at high risk for mortality. The full trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. Eligible patients were recruited between September 2014 and December 2015 and included those currently or recently hospitalized at Brigham and Women’s Hospital for management with at least 1 poor prognostic indicator (eMethods in Supplement 2). Those already enrolled in hospice or palliative care or anticipated to require cardiac surgery during the 6-month study duration were excluded. Analyses began in July 2016.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Eligible patients providing written informed consent were randomly allocated 1:1 to a structured, social worker–led palliative care intervention or usual care using a permuted block randomization scheme. All patients were identified and enrolled by the study coordinator (A.E.O.), who was blinded to the allocation sequence.

Patients allocated to the intervention group received a structured goals of care discussion based on the framework of the Serious Illness Conversation Guide5 conducted by a social worker (A.E.O.) with 5 years of palliative care experience and training in use of this approach. Conversations begun in the hospital were further developed in subsequent telephone or clinic-based encounters. Details of the intervention are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

The 2 primary study outcomes were (1) the percentage of patients in each group with documentation of advanced care preferences at 6 months by their usual health care professionals as ascertained from a blinded review of the electronic health record by 2 nonstudy clinicians (K.D. and K.W.) and (2) the percentage of patients with improvement in prognostic alignment, defined as revision of patient expectations of prognosis in a direction consistent with those of the treating physician (eMethods in Supplement 2). Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients with a Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment, advanced directive form, or hospice referral at 6 months (a proxy for physician-level advanced care planning conversations) as well as changes in spiritual well-being (using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being6), quality of life (using the abbreviated Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire7), depression (using the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale8), and anxiety (using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Questionnaire9). Rates of mortality, care preference documentation, and improvement in prognostic alignment by treatment group were compared in logistic regression models. Change scores from baseline to 6 months on the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-12, the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire were compared using linear regression adjusted for baseline scores, excluding patients who died or did not complete the 6-month assessment.

Results

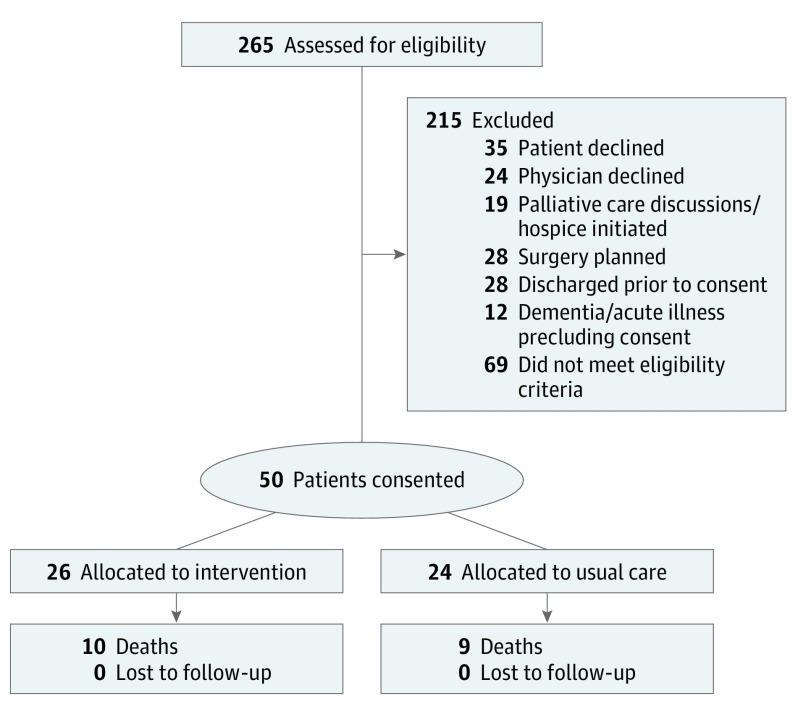

The flow of patient recruitment to the study is summarized in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the 50 eligible patients are summarized by treatment assignment in the Table. Of 50 patients, 26 (52%) were allocated to the intervention group, and 24 (48%) were allocated to usual care. Treating cardiovascular physicians anticipated death within 1 year in 32 patients (64%) but acknowledged that no conversation regarding end-of-life preferences had taken place for 25 patients (50%). By contrast, 27 patients (54%) had a self-predicted life expectancy of more than 5 years and 14 (28%), more than 10 years. Thirty-three patients (66%) indicated they wished to be informed of a physician-anticipated life expectancy less than 1 year, and 41 (82%) affirmed that their remaining lifespan had significant meaning and value. The observed mortality rate at 6 months was 38% with no difference between treatment groups.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Recruitment.

Table. Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Assignment.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group (n = 26) | Usual Care Group (n = 24) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.7 (11.2) | 69.2 (10.2) |

| Men | 14 (53.9) | 15 (62.5) |

| White | 17 (65.4) | 20 (83.3) |

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 30 (14) | 36 (17) |

| NYHA Class 3/4 | 16 (61.5) | 16 (66.7) |

| ICD or CRT-D at baseline | 14 (53.9) | 10 (41.7) |

| Previous HF hospitalization | 22 (86) | 21 (81) |

| ICU stay in last 12 mo | 5 (19.2) | 7 (29.2) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 35 (17) | 33 (14) |

| Advanced care planning | ||

| Health care proxy | 23 (88) | 18 (75) |

| MOLST | 1 (3.9) | 1 (4.1) |

| Any care preferences documented | 4 (15.4) | 4 (16.6) |

Abbreviations: CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (4-component MDRD); HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MOLST, Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

At 6 months, after a mean (SD) of 1.9 (1.2) contacts with the social worker, 17 patients (65%) in the intervention group and 8 patients (33%) in the usual care group had documentation by nonstudy staff of advanced care preferences based on blinded audit of the medical record (χ2 = 5.1; P = .02). Formal, physician-level documentation of end-of-life preferences was recorded in 15 patients (58%) in the intervention group and 5 (20%) in the usual care group (χ2 = 2.6; P = .10). Surviving patients assigned to the social worker–led intervention were much more likely to revise their baseline prognostic assessment in a direction consistent with the physician’s assessment (15 [94%] vs 4 [26%]; χ2 = 14.7; P < .001). (Figure 2). Among 6-month survivors, there was no difference in the change from baseline in depression, anxiety, spirituality, or quality-of-life scores between treatment groups (eTable in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Principal Study Outcomes at 180 Days by Treatment Assignment.

aDocumentation of advanced care preferences in electronic health records prior to death by any nonstudy staff.

bDocumentation of hospice referral or a physician order regarding end-of-life care (the Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment or Advanced Directive Form).

Discussion

This study provides important guidance for clinical practice. First, a simple risk stratification algorithm successfully identified a hospitalized HF population with an approximately 40% risk of death at 6 months; this simple screening in hospitals may facilitate targeting of limited palliative care personnel to patients most likely to benefit during transition to the outpatient setting. Second, patient and cardiologist estimates of prognosis were frequently misaligned, with most patients grossly overestimating their life expectancy. Most patients believed their life had meaning and value and expressed a willingness to engage goals of care conversations when appropriate. Third, routine initiation of goals of care conversations by a palliative care social worker, with triggered engagement of a palliative care physician as needed, was effective in improving communication between patients and their cardiology clinicians around end-of-life concerns without adverse impact on depression, anxiety, spiritual well-being, or quality of life. Together, these data suggest that palliative care engagement initiated by a social worker may be an effective method for improving advanced care planning and goals of care discussions in patients with advanced HF.

Our results amplify an evolving literature emphasizing the value of integrating palliative care into the management of patients with advanced HF. As in other studies,2 documentation of discussions about prognosis, goals of care, and advanced care planning was poor at baseline despite a high rate of physician-predicted mortality within 1 year and stated patient preference to be informed of limited life expectancy. Marked discrepancy in patient and physician estimates of prognosis emphasizes significant communication gaps, mirroring findings in other HF populations.10

In 2017, the Palliative Care in Heart Failure (PAL-HF) study by Rogers et al11 demonstrated the impact of a comprehensive, nurse practitioner–led, multidisciplinary palliative care intervention on quality of life and well-being in patients with advanced HF. Our findings reinforce and extend the PAL-HF findings by suggesting the potential for social worker–led interventions to similarly encourage and enhance goals of care discussions. Given our small sample size, the present study was likely underpowered to replicate the quality-of-life benefits seen in the PAL-HF study.11 However, because access to specialty palliative care at many centers is limited, the model in the present study may represent a less complex, lower-cost, scalable alternative for achieving palliative care goals that could be offered in a broader range of practice settings.

Limitations

Our study has important limitations including small sample size, short follow-up duration, and inability to blind patients and health care professionals to the intervention. In addition, social workers with the requisite training in palliative care may not be readily available at every center.

Conclusions

Use of a trained social worker to initiate longitudinal goals of care conversations may improve patient and physician engagement in palliative care and positively affect the overall quality of care for patients with advanced HF. Although more comprehensive, multidisciplinary palliative care interventions may also be effective, this focused approach may represent a cost-effective and scalable method that can be applied earlier in the course of illness to shepherd limited palliative care specialty resources and enhance the delivery of patient-centered care.

Trial Protocol.

eMethods. Additional Details of Study Methods

eTable. Patient-Reported Outcomes at Baseline and in 6 month Survivors

References

- 1.Greener DT, Quill T, Amir O, Szydlowski J, Gramling RE. Palliative care referral among patients hospitalized with advanced heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(10):1115-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kheirbek RE, Fletcher RD, Bakitas MA, et al. Discharge hospice referral and lower 30-day all-cause readmission in Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(4):733-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, et al. ; Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee . Advanced (stage D) heart failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail. 2015;21(6):519-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. ; American Heart Association; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia . Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, et al. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e009032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy: spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spertus JA, Jones PG. Development and validation of a short version of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(5):469-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambardekar AV, Thibodeau JT, DeVore AD, et al. Discordant perceptions of prognosis and treatment options between physicians and patients with advanced heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(9):663-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: the PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):331-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eMethods. Additional Details of Study Methods

eTable. Patient-Reported Outcomes at Baseline and in 6 month Survivors