Abstract

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is an established procedure for acquired and congenital disorders of the hematopoietic system. In 2016, there was a tendency for continued activity in this field with 43,636 HCT in 39,313 patients [16,507 allogeneic (42%), 22,806 autologous (58%)] reported by 679 centers in 49 countries in 2016. The main indications were myeloid malignancies 9547 (24%; 96% allogeneic), lymphoid malignancies 25,618 (65%; 20% allogeneic), solid tumors 1516 (4%; 2% allogeneic), and non-malignant disorders 2459 (6%; 85% allogeneic). There was a remarkable leveling off in the use of unrelated donor HCT being replaced by haploidentical HCT. Continued growth in allogeneic HCT for marrow failure, AML, and MPN was seen, whereas MDS appears stable. Allogeneic HCT for lymphoid malignancies vary in trend with increases for NHL and decreases for Hodgkin lymphoma and myeloma. Trends in CLL are not clear, with recent increases after a decrease in activity. In autologous HCT, the use in myeloma continues to expand but is stable in Hodgkin lymphoma. There is a notable increase in autologous HCT for autoimmune disease. These data reflect the most recent advances in the field, in which some trends and changes are likely to be related to development of non-transplant technologies.

Introduction

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is an established procedure for many disorders of the hematopoietic system including those of the immune system, and as enzyme replacement in metabolic disorders [1–4]. The activity survey of the European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), describing the status of HCT in Europe and affiliated countries, has become an instrument to observe trends and to monitor changes in technology [5–13]. The survey using a standardized structure captures the numbers of HCT from highly committed participating teams, divided by indication, donor type, and stem cell source. More recently, the survey has included information on novel cell therapies with hematopoietic stem cells for non-hematopoietic use, and the use of non-hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. This coincides with the interest of the World Health Organization WHO (www.who.org) in cell and tissue transplants and further stresses the need for adequate and timely information [14]. The analysis of the survey data spanning 26 years and amassing data on more than 660,000 transplants in over 580,000 patients has shown a continued and constant increase in the annual numbers of HCT and transplant rates for both allogeneic and autologous HCT.

This report is based on the 2016 survey data. In addition to transplant rates and indications, it focuses on the use of haploidentical donors for transplantation, including disease entities and stem cell source.

Patients and methods

Data collection and validation

Participating teams were invited to report data for 2016 as listed in Table 1. The survey allows the possibility to report additional information on the numbers of subsequent transplants performed as a result of relapse, rejection or those that are part of a planned sequential transplant protocol.

Table 1.

Numbers of HCT in Europe 2016 by indication, donor type, and stem cell source

| Transplant activity 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | ||||||||||||||||||

| Allogeneic | Autologous | Total | ||||||||||||||||

| Family | Unrelated | |||||||||||||||||

| HLA-id | Twin | Haplo≥2MM | Other family | BM | BM+ | Allo | Auto | Total | ||||||||||

| BM | PBPC | Cord | all | BM | PBSC | BM | PBPC | Cord | BM | PBPC | Cord | only | PBPC | Cord | ||||

| Myeloid malignancies | 396 | 2533 | 2 | 8 | 354 | 757 | 17 | 83 | 2 | 474 | 4408 | 156 | 8 | 349 | 9190 | 357 | 9547 | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 272 | 1825 | 1 | 5 | 256 | 569 | 13 | 70 | 2 | 302 | 2849 | 117 | 8 | 346 | 6281 | 354 | 6635 | |

| 1st complete remission | 185 | 1166 | 5 | 122 | 253 | 5 | 39 | 2 | 183 | 1535 | 72 | 6 | 289 | 3567 | 295 | 3862 | ||

| Not 1st complete remission | 68 | 438 | 1 | 100 | 233 | 7 | 25 | 83 | 792 | 33 | 2 | 52 | 1780 | 54 | 1834 | |||

| AML therapy related | 3 | 62 | 9 | 37 | 2 | 13 | 135 | 7 | 3 | 268 | 3 | 271 | ||||||

| AML from MDS/MPN | 16 | 159 | 25 | 46 | 1 | 4 | 23 | 387 | 5 | 2 | 666 | 2 | 668 | |||||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 32 | 102 | 1 | 15 | 24 | 1 | 4 | 25 | 174 | 6 | 1 | 384 | 1 | 385 | ||||

| Chronic phase | 13 | 51 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 75 | 2 | 1 | 173 | 1 | 174 | ||||

| Not chronic phase | 19 | 51 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 99 | 4 | 211 | 0 | 211 | ||||||||

| MDS or MD/MPN overlap | 86 | 419 | 2 | 56 | 130 | 2 | 8 | 131 | 1014 | 30 | 2 | 1878 | 2 | 1880 | ||||

| MPN | 6 | 187 | 1 | 27 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 647 | 0 | 647 | ||||||

| Lymphoid malignancies | 334 | 1495 | 6 | 11 | 192 | 462 | 15 | 56 | 1 | 414 | 1956 | 95 | 33 | 20,548 | 5037 | 20,581 | 25,618 | |

| Acute lymphatic leukemia | 263 | 734 | 6 | 3 | 96 | 237 | 12 | 33 | 1 | 333 | 859 | 74 | 5 | 85 | 2651 | 90 | 2741 | |

| 1st complete remission | 158 | 537 | 2 | 2 | 47 | 95 | 6 | 21 | 185 | 551 | 34 | 4 | 76 | 1638 | 80 | 1718 | ||

| not 1st complete remission | 105 | 197 | 4 | 1 | 49 | 142 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 148 | 308 | 40 | 1 | 9 | 1013 | 10 | 1023 | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 5 | 92 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 144 | 3 | 17 | 275 | 17 | 292 | |||||

| Plasma cell disorders—MM | 5 | 145 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 1 | 14 | 240 | 2 | 11,549 | 433 | 11,551 | 11,984 | |||||

| Plasma cell disorders—other | 2 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 380 | 30 | 380 | 410 | |||||||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 17 | 134 | 1 | 37 | 74 | 2 | 9 | 112 | 4 | 14 | 2031 | 390 | 2045 | 2435 | ||||

| Non Hodgkin lymphoma | 42 | 378 | 5 | 39 | 123 | 2 | 19 | 49 | 587 | 14 | 12 | 6486 | 1258 | 6498 | 7756 | |||

| Solid tumors | 3 | 23 | 1 | 6 | 42 | 1440 | 1 | 33 | 1483 | 1516 | ||||||||

| Neuroblastoma | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 459 | 20 | 479 | 499 | |||||||||

| Soft tissue sarcoma/Ewing | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 186 | 6 | 190 | 196 | ||||||||||

| Germinal tumors | 1 | 1 | 398 | 1 | 399 | 400 | ||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 21 | 0 | 21 | 21 | ||||||||||||||

| Other solid tumors | 3 | 3 | 17 | 376 | 1 | 6 | 394 | 400 | ||||||||||

| Non malignant disorders | 640 | 245 | 28 | 1 | 67 | 149 | 80 | 50 | 454 | 283 | 90 | 8 | 364 | 2087 | 372 | 2459 | ||

| Bone marrow failure—SAA | 193 | 119 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 26 | 9 | 5 | 152 | 107 | 11 | 5 | 642 | 5 | 647 | |||

| Bone marrow failure—other | 82 | 26 | 6 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 58 | 27 | 9 | 252 | 0 | 252 | |||||

| Thalassemia | 138 | 50 | 15 | 9 | 12 | 21 | 11 | 53 | 19 | 1 | 6 | 329 | 6 | 335 | ||||

| Sickle cell disease | 78 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 137 | 1 | 138 | |||||

| Primary Immune deficiencies | 116 | 27 | 2 | 14 | 79 | 25 | 16 | 134 | 97 | 40 | 2 | 3 | 550 | 5 | 555 | |||

| Inh. disorders of Metabolism | 28 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 40 | 21 | 27 | 3 | 1 | 150 | 4 | 154 | |||

| Auto immune disease | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 349 | 27 | 351 | 378 | |||||

| Others | 21 | 15 | 2 | 7 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 37 | 39 | 14 | 13 | 160 | 13 | 173 | |||

| Total patients | 1391 | 4291 | 38 | 20 | 620 | 1409 | 116 | 192 | 4 | 1379 | 6692 | 355 | 91 | 22,714 | 1 | 16,507 | 22,806 | 39,313 |

| Re/additional transplants | 41 | 212 | 4 | 4 | 73 | 204 | 6 | 22 | 1 | 73 | 459 | 35 | 7 | 3182 | 1134 | 3189 | 4323 | |

| Total transplants | 1432 | 4503 | 42 | 24 | 693 | 1613 | 122 | 214 | 5 | 1452 | 7151 | 390 | 98 | 25,896 | 1 | 17,641 | 25,995 | 43,636 |

Numbers of HCT in Europe 2016 by indication, donor type and stem cell source.

Supplementary information on the numbers of donor lymphocyte infusions, reduced intensity HCT and the numbers of pediatric HCT is also collected. Quality control measures included several independent systems: confirmation of validity of the entered data by the reporting team, selective comparison of the survey data with MED-A data sets in the EBMT Registry database and cross-checking with the National Registries.

Teams

A total of 707 centers from 49 countries were contacted for the 2016 survey (40 European and 9 affiliated countries); of which 679 teams reported. This corresponds to a 96% return rate and includes 577 active EBMT member teams. Twenty-eight active teams failed to report in 2016.

Contacted teams are listed in the online appendix in alphabetical order by country, city and EBMT center code, with their reported numbers of first and total HCT, and of first allogeneic and autologous HCT as supplementary material. The WHO regional office definitions were used to classify countries as European or Non-European. Eight non-European countries participated in the 2016 EBMT survey: Algeria, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Tunisia. Their data (2795 HCT in 2659 patients) from 32 actively transplanting teams make up 6.4% of the total data set and are included in all analyses [14].

Patient and transplant numbers

Wherever appropriate, patient numbers corresponding to the number of patients receiving a first transplant, and transplant numbers reflecting the total number of transplants performed are listed.

The term sibling donor includes HLA identical siblings and twins but not siblings with HLA mismatches. Unrelated donor transplants include HCT from matched or mismatched unrelated donors with peripheral blood and marrow as a stem cell source but not cord blood HCT. In the 2016 survey we collected separately the numbers of haplo-identical and other family member HCT. Haplo-identical transplants are being described as any family member with 2 or more loci mismatch within the loci HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 in GvH and/or HvG direction. Other family member donors are those related donors that are mismatched to a lesser degree than a full haplotype. Additional non first transplants may include multiple transplants defined as subsequent transplants within a planned double or triple autologous or allogeneic HCT protocol, and retransplants (autologous or allogeneic) defined as unplanned HCT for rejection or relapse after a previous HCT.

Transplant rates

Transplant rates, defined as the total number of HCT per 10 million inhabitants, were computed for each country without adjustments for patients who crossed borders and received their HCT in a foreign country. Population numbers for 2016 were obtained from Eurostats for the European countries (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/search_database) and the US census bureau database for the non-European countries (http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/rank.php).

Analysis

Wherever appropriate, the absolute numbers of transplanted patients, transplants or transplant rates are shown for specific countries, indications or transplant techniques. Myeloid malignancies include acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic or myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS/MPN), myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Lymphoid malignancies include acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and plasma cell disorders (PCD).The non-malignant disorders include bone marrow failure (BMF), thalassemia, sickle cell disease, primary immune disease (PID), inherited disease of metabolism (IDM) and auto immune disease (AID). Others include histiocytosis and rare disorders not included in the above. Trends shown over time include changes in absolute number of patients transplanted from 1990 to 2016, with exception to MPN and MDS, where these entities were grouped until 2004 and for autoimmune disease, where the first treatments were reported in 1997. We use graphical representation to indicate changes over time. To confirm trends we used SPSS to automatically fit the best exponentially smoothed, autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model without any further pre-specification. To detect possible deviations from trends, we show the observed and predicted counts as well as the 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Participating teams in 2016

Of the 679 teams, 432 (63%) performed both allogeneic and autologous transplants; 227 (34%) restricted their activity to autologous HCT, and 12 (2%) to allogeneic transplants only. Eight teams (1%) reported having performed no transplants in 2016 due to renovation or temporary closure of the transplant unit. Of the 679 active centers, 123 (18%) centers performed transplants on both adult and pediatric patients. An additional 112 (16%) centers were dedicated pediatric transplant centers and 444 (65%) centers performed transplants on adults only. Twenty-eight active teams failed to report in 2016 which when compared to previously reported data by these teams accounts for a possible 496 missing HCT.

Number of patients and transplants

In 2016, a total of 43,636 transplants were reported in 39,313 patients (first transplant); of these, 17,641 HCT (40%) were allogeneic and 25,995 (60%) autologous (Table 1). When compared with 2015 the total number of transplants increased by 3.5% (2.0% allogeneic HCT and 4.5% autologous HCT) [12], and the corresponding increase in numbers comparing 2006 to 2016 are 52% higher (68% allogeneic and 43% autologous). In patients receiving their first transplant in 2016, the increase was 3.0% for allogeneic HCT and 5.6% for autologous HCT. Within allogeneic HCT, the main part of the increase seen concerned pediatric patients (6.2% increase for pediatric, 2.1% increase for adult patients). Furthermore, there were 4323 second or subsequent transplants, being 1134 allogeneic, mainly to treat relapse or graft failure and 3189 autologous, the majority of which were most likely part of multiple transplant procedures such as either tandem procedures, or as salvage autologous transplants for plasma cell disorders, for which a recent randomized trial confirmed survival benefit [15]. In addition, 839 HCTs were reported as allogeneic HCT after a previous autologous HCT, and were mainly for lymphoma or plasma cell disorders. The total number of patients transplanted under the age of 18 in both dedicated and joint adult-pediatric units was 4690, an increase of 4.5% when compared to 2015, (3545 (+6.2%) allogeneic and 1145 (−0.6%) autologous HCT). Of these, 3206 patients (2498 allogeneic and 708 autologous) reporting a total of 3225 transplants were performed in dedicated pediatric centers.

Indications

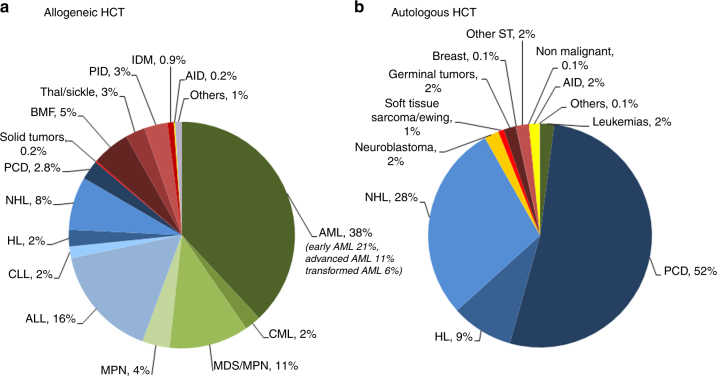

Indications for HCT in 2016 are listed in detail in Table 1. The main diseases were myeloid malignancies (AML, CML, MDS, and MPN): 9547 (24% of total; 96% of which were allogeneic); lymphoid malignancies (ALL, CLL, HL, NHL, and PCD): 25,618 (65%; 20% allogeneic); solid tumors: 1516 (4%; 2% allogeneic); non-malignant disorders: 2459 (6%; 85% allogeneic) and others: 173 (0.4%). As seen in previous years, the majority of HCT for lymphoid malignancies were autologous, while most transplants for myeloid malignancies were performed using stem cells from allogeneic donors. Autologous HCT for non-malignant disorders predominantly include patients with autoimmune disorders.

Figure 1a, b show as a pie graph the distribution of disease indications for allogeneic (Fig. 1a) and autologous (Fig. 1b) HCT. For allogeneic HCT, AML is the most frequent indication (38%), of these 21% were for patients in CR1, 11% for patients with more advanced disease and 6% for patients with transformed AML, either therapy-related or from MDS/MPN. Compared to 2015, there were increases in allogeneic HCT for ALL by 6.3%, MPN by 21.4%, and SAA by 13.4%.

Fig. 1.

Relative proportion of disease indications for HCT in Europe in 2016. a Allogeneic HCT. b Autologous HCT

Figure 2a shows the increasing use of autologous and allogeneic HCT over 26 years. In Figure 2b the use of different donors for allogeneic HCT is shown. For the first time since 1990, the continued increase in use of unrelated donor HCT appears to be leveling off. Comparing observed and expected values of unrelated donor HCTs suggests that since 2015 a substantially lower count of unrelated donor transplants than expected was observed although this deviance remains just within the 95% confidence limits using the ARIMA model (see supplementary table 1 and Figure 1). Matched sibling donor HCT appears to be increasing slowly, and there is a clear and continued growth in the use of haploidentical donor HCT. The use of cord blood transplantation appears to stabilize in numbers after a decrease from 2010 to 2015 as shown in Figure 2c. European maps depicting transplant rates by country are provided in the supplementary section (Supplementary Figure 2a, 2b).

Fig. 2.

Trend in the absolute numbers of HCT in Europe 1990–2016. a Trend in allogeneic and autologous HCT. b Changes in donor choice. c Trend in cord blood HCT

Important trends in 2016

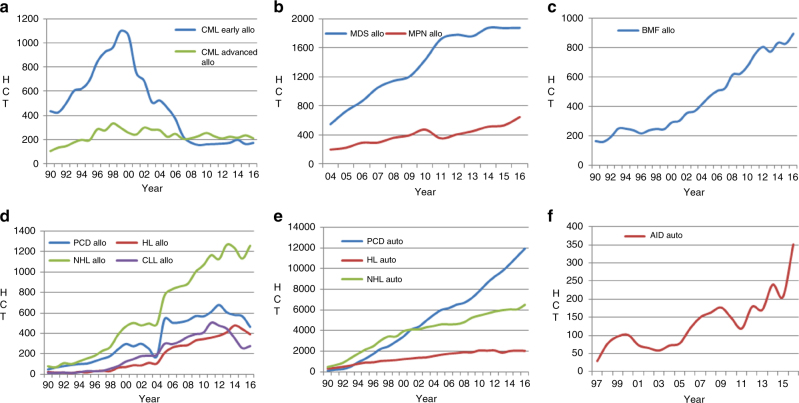

Figure 3 shows specific trends over time for some indications highlighted here for special interest. Figure 3a depicts the use of allogeneic HCT for CML in first chronic phase and more advanced disease. It is of interest to see that, after the major decrease due to the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in 2000 there is a stable number of approximately 400 patients receiving an allogeneic HCT annually between 2008 and 2016. Figure 3b shows the corresponding graphs for allogeneic HCT for MDS and MPN. The time axis starts in 2004 as MDS and MPN information was grouped until this time. It appears that the use of allogeneic HCT is leveling off in MDS since 2014 whereas for MPN it continues to increase. Figure 3c shows allogeneic HCT for marrow failure with continuing increased use over time. Allogeneic HCT for lymphoid malignancies is shown in Figure 3d. There is a mixed picture with increasing numbers for NHL and decreasing numbers for PCD and HL. There is a slight increase of 8% in use of allogeneic HCT in CLL, after a major decrease by 49% between the years 2011 and 2015. Trends in autologous HCT are shown in Figure 3e, where use in PCD shows a continuous increase, less so for NHL and a leveling off in HL. Figure 3f shows trends in autologous HCT in AID with a sharp increase in the last 5 years, mostly driven by autologous HCT for multiple sclerosis in specialized centers. Among allogeneic HCT, 6878 were performed using non myeloablative conditioning. This comprises 39% of all allogeneic HCT, and has remained stable over the last 8 years.

Fig. 3.

Major trends in disease indication in Europe 1990–2016. a Allogeneic HCT for CML in early and late stage. b Allogeneic HCT for MDS and MPN. c Allogeneic HCT for BMF. d Allogeneic HCT for lymphoproliferative disorders. e Autologous HCT for lymphoproliferative disorders. f Autologous HCT for auto immune disease

To address the question as to whether sibling, unrelated and haploidentical HCT were used differently according to available resources, we looked at the transplant rates over the last 5 years in the three income groups; very high (>41,000 USD), high (8200–41,000 USD) and upper middle income groups (2080–8200 USD) defined as gross national income in USD per capita according to World Bank criteria (http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/WV.1). Table 2 shows that unrelated donor transplant rates vary greatly by income. Rates of haploidentical HCT were higher in the high-income group when compared to the very high-income group. This argues in favor of haploidentical HCT being used in place of unrelated HCT, possibly based in part on economic considerations. In the upper middle income groups, rates of alternative donor HCT were equally low, when compared to sibling donor HCT, possibly pointing toward restricting HCT technology to the best possible donor in a situation of limited resources [16].

Table 2.

Transplant rates per 10 million inhabitants during the years 2012 and 2016 by donor choice and income group

| Transplant rates per 10 million inhabitants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | |||

| Identical Sibling | Haploidentical family | Unrelated | |

| Income group | |||

| Very high | 390 | 77 | 978 |

| High | 283 | 106 | 321 |

| Upper middle | 102 | 16 | 16 |

Transplant rates per 10 million inhabitants (TR) over the years 2012–2016 by donor choice and income group

Cellular therapy use

Table 3 shows cellular therapies performed in EBMT centers in 2016. There were 2879 patients receiving donor lymphocyte infusions, a similar number to that in the 2015 report (2941). A total of 1153 patients received other forms of cellular therapy, most commonly mesenchymal stromal cells (n = 491), mainly to treat graft versus host disease. The second most common indication was expanded/selected T lymphocytes to treat infections (n = 157) or malignancy (n = 35). Only very few (n = 36) cellular therapies using genetically modified allogeneic or autologous T-lymphocytes were reported in 2016. Mesenchymal stromal cells have been used for over a decade now and continue to increase (supplementary figure 3) [17–19].

Table 3.

Non HCT cellular therapies using manipulated cells in 2016

| Number of patients | DLI | MSC | NK cells | Selected/expanded T cells or CIK | Regulatory T cells (TREGS) | Genetically modified T cells | Dendritic cells | Expanded CD34+ cells | Genetically modified CD34+ cells | Other | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | Allo | Auto | ||

| GvHD | 421 | 2 | 4 | 31 | 1 | 11 | 36 | ||||||||||||

| Graft enhancement | 722 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 20 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 75 | 22 | |||||||||

| Autoimmune dis. | 9 | 19 | |||||||||||||||||

| Genetic disease | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Infection | 4 | 157 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Malignancy | 1 | 9 | 32 | 3 | 28 | 6 | 29 | 3 | 45 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| DLI for residual disease | 458 | ||||||||||||||||||

| DLI for relapse | 1329 | ||||||||||||||||||

| DLI per protocol | 370 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Regenerative medicine | 5 | 8 | 1 | 14 | 79 | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 2879 | 458 | 33 | 14 | 0 | 213 | 3 | 59 | 0 | 7 | 29 | 3 | 45 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 124 | 139 |

Numbers of cellular therapies in Europe 2016 by indication, donor type and cell source

Discussion

The EBMT activity survey has been conducted annually since 1990 [7]. The 2010 survey reported for the first time more than 30,000 patients transplanted in a given year, and more than >40,000 transplants in 2014. Once again, transplant numbers continue to increase across Europe.

Of interest, autologous HCT continues to expand (4.5%) at a higher rate than allogeneic HCT (2.0%) (Fig. 2a). In allogeneic HCT some indications continue to increase but not in others. Furthermore, while the use of unrelated donors is no longer increasing, the use of sibling donors continues to do so but more slowly than in previous years. Within haploidentical HCT we see a continued growth. To analyze whether these, albeit subtle changes, were related to resource use, we calculated transplant rates according to wealth of particular countries. The majority of unrelated donor HCT was done in very high-income countries, whereas the less wealthy countries used haploidentical HCT more frequently than unrelated donors as a stem cell source pointing to some economic impact on donor choices. Of interest, all of the highest income countries have a national unrelated donor registry when compared to only 36% of the upper middle income countries. The least wealthy countries concentrated on sibling donor HCT and used alternative donors the least. There is also a hint toward stabilization in the use of cord blood as a stem cell source (Fig. 2c), 34% of which were for non malignant diseases. We do not have information on the age of the patients receiving cord blood as a stem cell source, however 43% were done in dedicated pediatric centers. As shown in Fig. 2b the phenomenal growth of unrelated donor HCT between 2004 and 2015, appears to level off. Annual growth of unrelated donor HCT was 13% between the years 2006-2010 and only 1.3% between the years 2014-2016. Future analyses will show whether this leveling off is a true effect or just due to annual variation. As the observation spans 3 years, it would indicate otherwise. Obviously, such trends, if confirmed, will be important for use of medical resources. The success of unrelated donor HCT is due to the intensive work done by donor registries, recruiting and providing well matched donors for many patients. Clearly it is highly speculative to predict future developments, but it appears as if haploidentical HCT is the main competitor. This has been recognized by the transplant community, and randomized clinical trials comparing unrelated donor HCT to haploidentical donor HCT are underway. Results of these trials will undoubtedly be instrumental to guide future recommendations.

Among indications for allogeneic HCT, its use in CLL appears to stabilize or increase, after dropping in the previous years. The majority of allogeneic HCT continues to be for myeloid neoplasia, with AML in the lead, with more frequent use in MPN but no further increase in MDS. Additional follow-up will show whether these trends persist. The trend of allogeneic HCT in CML is interesting; the drop in transplant numbers seen after the introduction of kinase inhibitors appears now to have left a stable number of around 400 CML patients being transplanted in chronic or more advanced phases, most likely after kinase inhibitor failure [20]. Allogeneic HCT for lymphoid neoplasia continues to be used variably, with an increased indication for in ALL and NHL and less use in HL and PCD. Over 800 patients with marrow failure are transplanted each year, and the numbers appear to grow, in spite of alternative treatment being developed. Continued growth in transplants for marrow failure includes both acquired and congenital marrow failure in all donor types and with unrelated and haploidentical HCT accounting for 466 patients as compared to sibling donor HCT with 428 patients in 2016, suggesting a slight preference for alternative donor HCT over sibling donor HCT.

Autologous HCT has been continuously more indicated for myeloma, possibly a result of randomized controlled trials confirming benefit of autologous HCT in the era of modern therapies [21]. Indications for NHL increase at a lower rate (7.0%) and appear to stabilize in HL possibly due to development of monoclonal antibodies and check point inhibitors for this disease [22]. This pertains to allogeneic HCT for HL as well. Autologous HCT for autoimmune disease has seen a major increase, largely due to a number of centers using this technology to treat multiple sclerosis [23, 24].

The section on cellular therapies shows the gradual increasing use of mesenchymal stromal cells, most commonly to treat graft versus host disease. There is a growth in the use of cell therapy use to treat infectious complications such as CMV or EBV, using selected and/or expanded T-cell products. Of note, only a few genetically modified T-cell therapies have been reported. Whereas the authors are confident that transplant numbers are reported correctly by an overwhelming majority of EBMT member or associated centers, they are less sure about the reporting on cellular therapies. The currently available data state, that although many groups work on genetically modified T-cells for immunotherapy only a limited number of patients have been treated so far. As cellular therapies, in particular CAR-T cells [25] have become commercially available, and given that cell collections are restricted to centers experienced and accredited in apheresis [26], it is most important that EBMT centers continue the well-established practice of transparently sharing data on activity of cellular products used and on outcome of patients. The EBMT registry database collecting data on transplant outcome since 1973, currently including cellular therapy data, and accreditation by JACIE are the tools within the EBMT to assure highest levels of scientific exchange and assurance of qualities.

Disclaimer

Writing of the manuscript was the sole responsibility of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all the participating teams and their staff (listed in the online Appendix) for their cooperation. The staff at the EBMT Co-ordination offices; Barcelona, Paris, London (C Ruiz de Elvira), the national registries; the Austrian Registry (ASCTR) (H Greinix, B Lindner), the Belgium Registry (Y Beguin), the Czech Registry (P Zak, M Trnkova), the French Registry (SFGM-TC) (J-O Bay, N Raus), the German Registry (DRST) (H Ottinger, H Neidlinger), the Italian Registry (GITMO) (F Bonifazi, B Bruno, E Oldani), the Dutch Registry (JJ Cornelissen, M Groenendijk), the Spanish Registry (GETH) (C Solano, A Cedillo), the Swiss Registry (SBST) (U Schanz, E Buhrfeind) and the British Registry (BSBMT) (J Perry). We also thank D John for database support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41409-018-0153-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelbaum FR. Hematopoietic-cell transplantation at 50. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1472–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sureda A, Bader P, Cesaro S, Dreger P, Duarte RF, Dufour C, et al. Indications for allo- and auto-SCT for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current practice in Europe, 2015. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1037–56. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, Pasquini MC, Bouzas LF, Yoshimi A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA. 2010;303:1617–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gratwohl A, Pasquini MC, Aljurf M, Atsuta Y, Baldomero H, Foeken L, et al. One million haemopoietic stem-cell transplants: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e91–e100. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Schwendener A, Gratwohl M, Apperley J, Frauendorfer K, et al. The EBMT activity survey 2008 impact of team size, team density and new trends. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:174–91. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gratwohl A. Bone marrow transplantation activity in Europe 1990. Report from the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplant (EBMT) Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;8:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Horisberger B, Schmid C, Passweg J, Urbano-Ispizua A. Accreditation Committee of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Current trends in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Europe. Blood. 2002;100:2374–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Schwendener A, Rocha V, Apperley J, Frauendorfer K, et al. The EBMT activity survey 2007 with focus on allogeneic HSCT for AML and novel cellular therapies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:275–91. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gratwohl A, Schwendener A, Baldomero H, Gratwohl M, Apperley J, Niederwieser D, et al. Changes in use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; a model for diffusion of medical technology. Haematologica. 2010;95:637–43. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.015586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Peters C, Gaspar HB, Cesaro S, Dreger P, et al. Hematopoietic SCT in Europe: data and trends in 2012 with special consideration of pediatric transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:744–50. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Cesaro S, Dreger P, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Europe 2014: more than 40000 transplants annually. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:786–92. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Duarte RF, Dufour C, et al. Use of haploidentical stem cell transplantation continues to increase: the 2015 European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplant activity survey report. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:811–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organisation. Transplantation. Geneva: WHO (http://www.who.int/topics/transplantation/en/)

- 15.Cook G, Williams C, Brown JM, Cairns DA, Cavenagh J, Snowden JA, et al. High-dose chemotherapy plus autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation therapy in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma after previous autologous stem-cell transplantation (NCRI Myeloma X Relapse [Intensive trial]): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:874–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foeken LM, Green A, Hurley CK, Marry E, Wiegand T, Oudshoorn M. Monitoring the international use of unrelated donors for transplantation: the WMDA annual reports. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:811–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ireland H, Gay MHP, Baldomero H, De Angelis B, Baharvand H, Lowdell MW, et al. The survey on cellular and tissue-engineered therapies in Europe and neighboring Eurasian countries in 2014 and 2015. Cytotherapy. 2017;20:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonini C, Mondino A. Adoptive T-cell therapy for cancer: the era of engineered T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2457–69. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolar J, Le Blanc K, Keating A, Blazar BR. Concise review: hitting the right spot with mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1446–55. doi: 10.1002/stem.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Cesaro S, Dreger P, et al. Impact of drug development on the use of stem cell transplantation: a report by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:191–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, Leleu X, Caillot D, Escoffre M, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone with transplantation for myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, Zinzani PL, Timmerman JM, Ansell S, et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1283–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30167-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancardi GL, Sormani MP, Gualandi F, Saiz A, Carreras E, Merelli E, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a phase II trial. Neurology. 2015;84:981–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snowden JA, Badoglio M, Labopin M, Giebel S, McGrath E, Marjanovic Z, et al. Evolution, trends, outcomes, and economics of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe autoimmune diseases. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2742–55. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1507–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snowden JA, McGrath E, Duarte RF, et al. JACIE accreditation for blood and marrow transplantation: past, present and future directions of an international model for healthcare quality improvement. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:1367–71. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.