Abstract

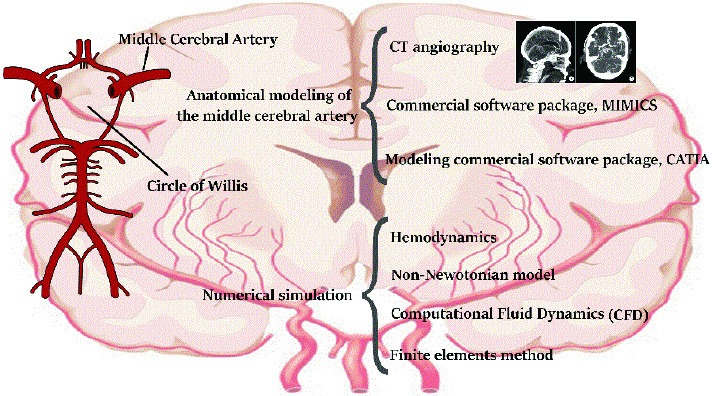

Introduction: The middle cerebral artery (MCA) is one of the three major paired arteries that supply the blood to the cerebrum. In the present study, the three-dimensional (3D) blood flow in the left MCA was numerically simulated by using the medical imaging.

Methods: The arterial geometry was obtained by applying the CT angiography of the MCA of a 75-year-old man. The blood flow was assumed to be laminar and unsteady. Numerical simulations were done by commercial software package COMSOL Multiphysics 5.2. In this software, the Galerkin’s finite element method was applied to solve the governing equations.

Results: It was found that the results obtained for the Newtonian and non-Newtonian models of blood do not differ from each other significantly. Thus, the Newtonian model for blood flow in the MCA is acceptable. Also, the most susceptible region of the MCA for Atherosclerosis was detected.

Conclusion: It can be concluded that the application of the Newtonian model for the blood flowing in the MCA is acceptable. Also, atherosclerosis has the potential to occur at the middle of a branch of the MCA which has the highest geometrical curvature.

Keywords: Middle cerebral artery, Hemodynamics, Non-Newtonian model, Finite element method

Introduction

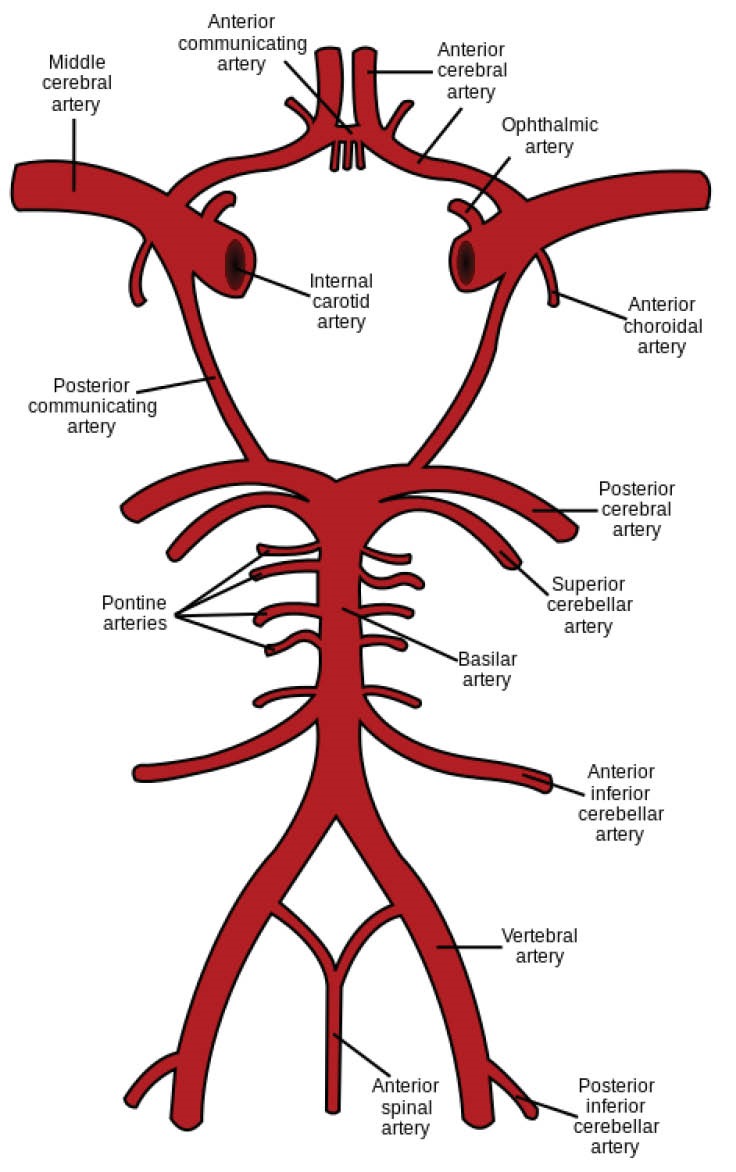

The statistic reports by the World Health Organization (WHO) reveal that from 2012, stroke is the second leading cause of death in the world. The most prevalent type of stroke is an ischemic stroke which is usually caused by a blood clot or a stenosis in a brain artery. Both the blood clot and stenosis interrupt the normal blood flow in a brain artery. Thus, some brain cells face the lack of oxygen and nutrients and begin to die. Ischemic stroke mostly occurs in the middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) and their branches. Fig. 1 shows MCAs symmetrically bifurcated from the circle of Willis. This circular anatomical connectivity between the brain arteries is located at the base of the brain and is the main distributor of oxygenated blood throughout the cerebral mass. Blood comes into the circle of Willis through two symmetric internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and also 2 symmetric vertebral arteries (VAs) which are joined each other at the basilar artery (BA). Blood symmetrically leaves the circle through 2 MCAs, 2 anterior cerebral arteries, and 2 posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of circle of Willis.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become a worthy tool in the investigation on hemodynamics in the cerebral arteries. It plays an important role in the better understanding of the physical mechanisms which govern the formation and progression of disorders, for instance, the aneurysms, atherogenesis, and atherosclerosis in the brain arteries. The governing equations of cerebral hemodynamics are the Navier–Stokes equations in which the blood flow through a brain artery or a cerebral arterial network is considered incompressible and viscous. Numerous researchers have conducted numerical simulations on the cerebral hemodynamics. Valencia and Solis1 by using the finite element method studied numerically the three dimensional, unsteady, and laminar flow of the Newtonian blood under the physiologically realistic pulsatile conditions in a saccular cerebral aneurysm formed exactly where the BA is bifurcated to join the circle of Willis. To understand better the role of different factors contributing to the initiation, growth, and rupture of a saccular cerebral aneurysm formed where the MACs are bifurcated from the circle of Willis, such as the hemodynamic characteristics and the bifurcation morphology, Torii et al2 by using the Deforming-Spatial-Domain/Stabilized Space-Time (DSD/SST) method studied numerically the three dimensional, unsteady, and laminar Newtonian blood flow with the pulsatile boundary conditions in the aforementioned aneurysm. Jozwik and Obidowski3 by taking into consideration the conceivable difference in the inner diameter of the left and right vertebral arteries before joining together to form the BA investigated numerically on the three dimensional, unsteady, and turbulent non-Newtonian blood flow through them. In their study, the physiologically realistic pulsatile velocity and pressure at the inlet and outlet boundaries were approximated with a Fourier series and the turbulence model of SST k-ω was adopted. By using the Gambit and Fluent commercial software packages, Muller et al4 studied numerically the three dimensional, laminar, and unsteady Newtonian blood flow inside a saccular cerebral aneurysm formed on the anterior communicating artery (ACA) (see Fig. 1) under the pulsatile boundary conditions. To capture the geometry of ACA, a medical imaging technique was applied to their work. Qiu et al5 by utilizing the commercial CFD package ANSYS Fluent studied numerically the effects of a high-porosity mesh (HPM) implanted stent on the hemodynamic characteristics, for example, the velocity and pressure fields, in a saccular cerebral aneurysm formed exactly where 2 PCAs are bifurcated from the BA to join the circle of Willis. In their research, the three dimensional, unsteady, laminar, and pulsating Newtonian blood flow was simulated. Reorowicz et al6 conducted three dimensional CFD simulations by applying the commercial software package ANSYS CFX for the three different arterial anatomies of the circle of Willis. They employed the SST k-ω turbulence model, a modified power low model for the non-Newtonian blood, and also the realistic pulsatile boundary conditions for the unsteady flow in their work. Nam et al7 used the microfluidic approach for the circle of Willis and then simulated it numerically by the commercial CFD package COMSOL Multiphysics. They focused on the influence of morphology of the circle of Willis on the formation and growth of a cerebral aneurysm in it. The 3 dimensional, steady, and laminar flow of the Newtonian blood was considered in their study. Tazraei et al8 investigated numerically on the blood-hammer phenomenon in the PCAs. They performed their simulations for the two dimensional, unsteady, and laminar blood flow. In their work, both the Newtonian model and the non-Newtonian Carreau model were used for the blood and the governing equations were solved by using an enhanced characteristics CFD scheme. Chnafa et al9 introduced an improved reduced-order model for the three dimensional, steady, and pulsating Newtonian blood flow through the cerebral arterial networks. By considering the database of three dimensional CFD models for the saccular cerebral aneurysm formed on an MCA, they tested the aptitude of their model.

It seems that the hemodynamics in the cerebral arteries recently has been less investigated numerically in the literature comparing to it in the cardiovascular arteries.10-20 It implies that the numerical information on the cerebral hemodynamics is still drastically lacking. This encouraged us to conduct the present research to show the noticeable capability of CFD in providing great details for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral disorders. Furthermore, since some researchers employed the Newtonian model for the blood in the cerebral hemodynamics in the circle of Willis and some other researchers applied the non-Newtonian model for it, then this disparity in their attitude to blood flowing in the Circle of Willis was another motivation for our study to numerically show which one of these models is actually better. This paper aimed to focus on the unsteady, laminar, and three-dimensional (3D) blood flow through an MCA.

Materials and Methods

Anatomical modeling

The 3D model of MCA has been constructed passing consecutive three steps. At the first step by using the CT angiography, the geometrical image of an MCA of a 75-year-old man with the inner diameter of 5 mm was captured. Then, this image was segmented by the commercial software package MIMICS followed by the creation of 3D image. At the final, the model which is the 3D output of the image processing was constructed by the modeling commercial software package CATIA.

Governing equations

The incompressible blood flow through the MCA was assumed to be three dimensional, unsteady, laminar, and viscous. So, its governing equations for the conservation of mass and momentum are written as follows:

| Eq. (1) |

| Eq. (2) |

where ρ and μ are the blood’s density and viscosity, respectively, P is the pressure, is the gravity, and is the velocity vector. If the blood is considered as a Newtonian fluid, its viscosity is constant, but if it is considered as a non-Newtonian fluid, its viscosity varies with the shear rate . In our research, the Carreau-Yasuda model8 was applied for the non-Newtonian blood. In this model, the viscosity is defined as:

| Eq. (3) |

where μ0=0.00568 Pa.s, μ0=0.00345 Pa.s, n= 3568, λ=3.313 s and the constant density of blood equals 1048 kg/m3.

Numerical method and boundary conditions

In this research, the numerical simulations of the three dimensional, unsteady, and laminar flow of blood in an MCA were investigated by the commercial CFD package COMSOL Multiphysics 5.2 in which the unstructured grid was generated by the tetrahedral elements and the Galerkin’s finite element method was used to solve the governing equations. The aforementioned smooth grid with the appropriate number of elements was clustered in the vicinity of the tubular wall of the MCA in order to better capture the hemodynamics in it.

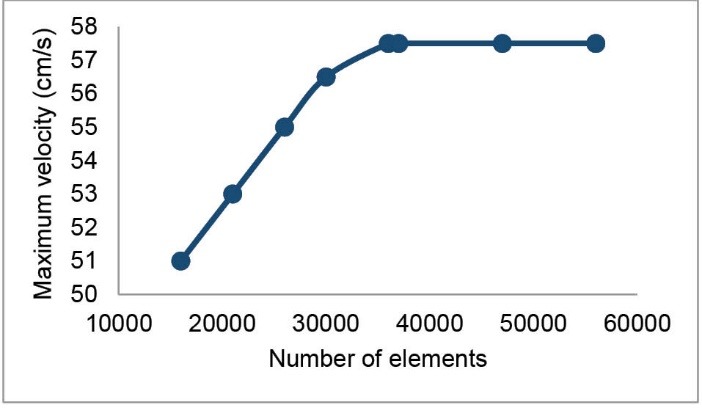

To verify the independence of simulations from the grid, eight grids with a varied number of elements were constructed. Fig. 2 shows the maximum velocity of blood at the apex of the main bifurcation of MCA at the peak systole for these grids. It is seen that the independence of simulations from the grid has been achieved for a grid with 37 019 tetrahedral elements. This grid was used for the MCA.

Fig. 2.

The test carried out for the independence of simulations from the grid. The blood gets its maximum velocity at the apex of the main bifurcation at the peak systole.

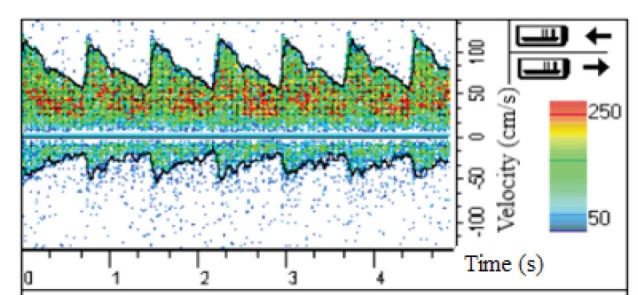

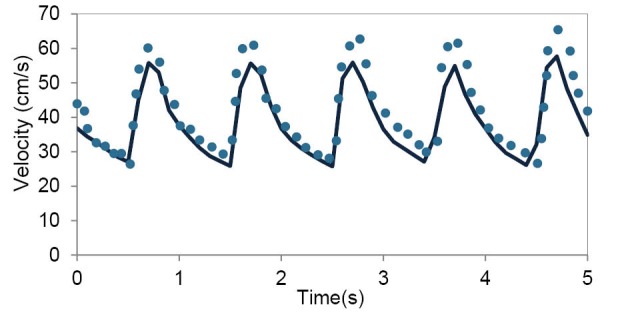

With the cooperation of the aforementioned 75-year-old man, the velocity profile at the apex of the main bifurcation of his MCA was obtained by Doppler ultrasound test. Also, the inlet velocity profile, obtained by this way, was applied at the inlet of the MCA which has been represented in Fig. 3. At the outlet of MCA, the constant pressure equal to 1440 Pa was applied. The no-slip boundary conditions were utilized at the tubular wall which was assumed to be rigid. This assumption is acceptable for very narrow arteries.

Fig. 3.

The inlet velocity profile obtained by Doppler ultrasound test.

To validate the simulations, the velocity profile at the apex of the main bifurcation of MCA was compared with the data obtained by Doppler ultrasound test. This comparison shows a good agreement in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between the velocity profile obtained by the numerical simulations and data obtained by Doppler ultrasound test at the apex of the main bifurcation of MCA over the multiple cardiac cycle.

Results

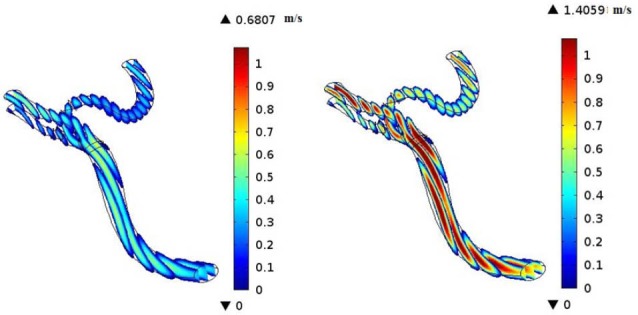

CFD simulations have become valuable tools for the better understanding of the human’s cerebral system, recently. In the present investigation, we focused on the hemodynamics in MCA. It was found that the blood achieves its maximum velocity at the apex of the main bifurcation at the peak systole. This maximum velocity is approximately 57% higher than the maximum velocity of blood at the same place, at the peak diastole. This is expected because the blood has a driving pressure created by the heart during the systole phase. The blood velocity distributions in the systole and diastole phases have been represented in Fig. 5. Fig. 6 depicts the blood streamlines through the MCA and its branches. It was seen that the blood gets its minimum velocity at the middle of the branch (1) and its maximum velocity at the apex of the main bifurcation.

Fig. 5.

Velocity distributions at diastole phase (left) and systole phase (right).

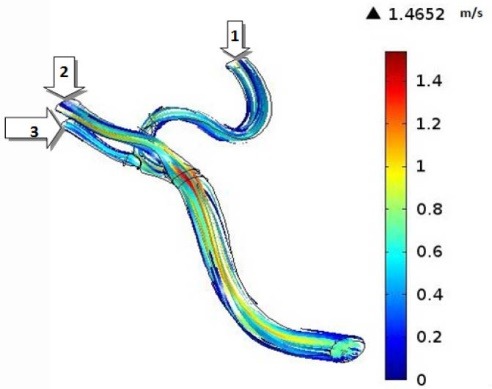

Fig. 6.

Streamlines through the MCA at the peak systole.

The volumetric flow rates have been reported in Table 1. It is obvious that the branch (1) has the minimum flow rate at the peak systole among the branches (1), (2), and (3) which is the result of the high curvature of this branch. So, it seems that the formation of atherosclerotic plaques at the branch (1) due to the low blood velocity could be risky.

Table 1. Volumetric flow rate (mL/s) through the MCA and its branches .

| Inlet | Branch(1) | Branch(2) | Branch(3) |

| 3.72 | 0.8 | 1.88 | 1.04 |

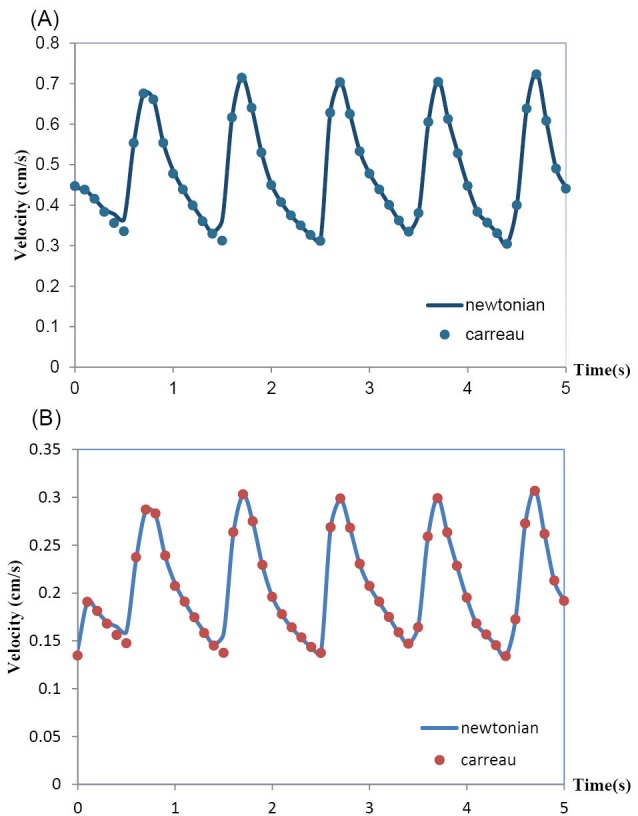

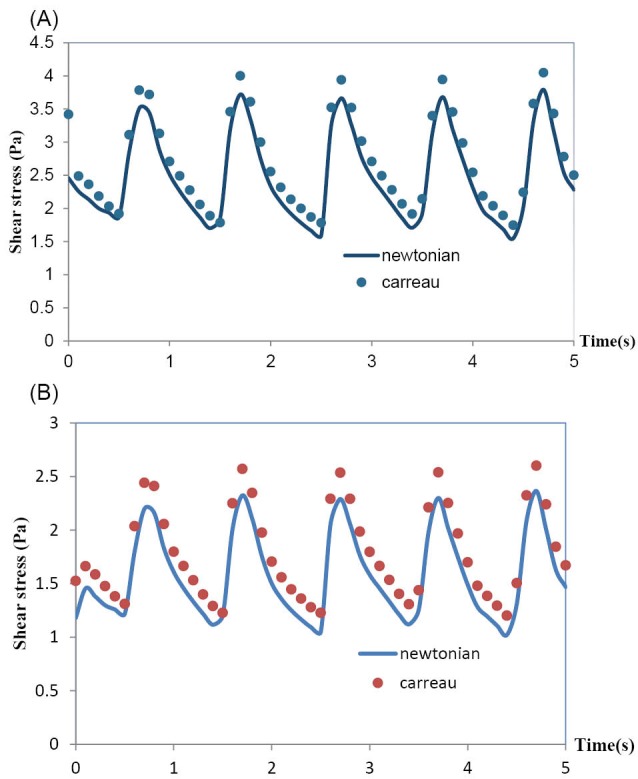

The effects of the rheological model of blood on the hemodynamics in MCA have been shown in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8. Both Newtonian and non-Newtonian simulations were performed with exactly the same boundary conditions. These figures respectively show the pulsatile velocity and wall shear stress profiles at two critical cross sections of MCA, namely, at the apex of the main bifurcation where the wall shear stress is maximum and at the middle of the branch (1), where the wall shear stress is minimum, in the cardiac cycle. In these figures, the results obtained for the blood with the Newtonian model and the blood with the non-Newtonian model have been compared. It is clearly seen that the influence of rheological model of blood on the wall shear stress profiles is more than the velocity profiles. Also, it is clearly observed that the obtained results for both the Newtonian and non-Newtonian models ensue the same pattern and there is not quantitatively considerable difference between them.

Fig. 7.

(A) Velocity profile at the apex of main bifurcation of the MCA. (B) Velocity profile at the middle of branch(1) of the MCA.

Fig. 8.

(A) Wall shear stress at the apex of main bifurcation of the MCA. (B) Wall shear stress at the middle of branch (1) of the MCA.

Conclusion

In the present numerical research, two different rheological models of blood have been employed to study the effect of them on the hemodynamics in an MCA. The arterial geometry was captured by applying the CT image of the MCA of a 75-year-old male and the pulsatile unsteady conditions based on Doppler ultrasound test data were considered.

The results showed that the wall shear stress profiles are more influenced by the non-Newtonian model in comparison with the velocity profiles. This is associated with the fact that the magnitude of the viscous term in the governing equations directly is involved in the calculation of shear stress. Because of the negligible difference between the results obtained for the Newtonian and non-Newtonian models, it is found that the assumption of Newtonian blood is acceptable for the case of MCA.

Furthermore, the most susceptible region in the MCA for atherosclerosis, which is one of the major global causes of death, was detected. In atherosclerosis duo to deposits formed on the artery wall, the cross-section of blood flow become narrowed. This present numerical research shows the capability of CFD in doing an investigation on the human’s cerebral system.

Ethical approval

None to be declared.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interests to be reported.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ The computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is employed to numerically investigate the hemodynamics in the blood arteries.

What is new here?

The hemodynamics in an MCA has been numerically studied based on the finite element method (FEM).

√ Both the Newtonian and non-Newtonian rheological models have been examined for the blood.

√ It was found that the Newtonian model is acceptable for the blood flowing through the MCA.

References

- 1.Valencia A, Solis F. Blood flow dynamics and arterial wall interaction in a saccular aneurysm model of the basilar artery. Comput Struct. 2006;84:1326–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruc.2006.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torii R, Oshima M, Kobayashi T, Takagi K, Tezduyar TE. Fluid–structure interaction modeling of blood flow and cerebral aneurysm: Significance of artery and aneurysm shapes. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2009;198:3613–3621. doi: 10.1016/j.cma.2008.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jozwik K, Obidowski D. Numerical simulations of the blood flow through vertebral arteries. J Biomech. 2010;43:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller JD, Jitsumura M, Muller-Kronast NHF. Sensitivity of flow simulations in a cerebral aneurysm. J Biomech. 2012;45:2539–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu X, Fei Zh, Zhang J, Cao Zh. Influence of high-porosity mesh stent on hemodynamics of intracranial aneurysm: A computational study. J Hydrodynam. 2013;25(6):848–855. doi: 10.1016/S1001-6058(13)60432-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reorowicz P, Obidowski D, Klosinski P, Szubert W, Stefanczyk L, Jozwik K. Numerical simulations of the blood flow in the patient-specific arterial cerebral circle region. J Biomech. 2014;47:1642–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nam SW, Choi S, Cheong Y, Park HK. Evaluation of aneurysm-associated wall shear stress related to morphological variations of Circle of Willis using a microfluidic device. J Biomech. 2015;48(2):348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tazraei P, Riasi A, Takabi B. The influence of the non-Newtonian properties of blood on blood-hammer through the posterior cerebral artery. Math Biosci. 2015;264:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chnafa C, Valen-Sendstad K, Brina O, Pereira VM, Steinman DA. Improved reduced-order modelling of cerebrovascular flow distribution by accounting for arterial bifurcation pressure drops. J Biomech. 2017;51:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esmaily Moghadam M, Vignon-Clementel IE, Figliola R, Marsden AL. for the Modeling Of Congenital Hearts Alliance (MOCHA) Investigators. A modular numerical method for implicit 0D/3D coupling in cardiovascular finite element simulations. J Comput Phys. 2013;244:63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2012.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azaouzi M, Makradi A, Petit J, Belouettar S, Polit O. On the numerical investigation of cardiovascular balloon-expandable stent using finite element method. Comput Mater Sci. 2013;79:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2013.05.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govindaraju K, Kamangar S, Anjum Badruddin I, Viswanathan GN, Badarudin A, Salman Ahmed NJ. Effect of porous media of the stenosed artery wall to the coronary physiological diagnostic parameter: A computational fluid dynamic analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alimohammadi M, Agu O, Balabani S, Díaz-Zuccarini V. Development of a patient-specific simulation tool to analyze aorticdissections: Assessment of mixed patient-specific flow and pressure boundary conditions. Med Eng Phys. 2014;36:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu G, Wu J, Ghista DN, Huang W, Wong KKL. Hemodynamic characterization of transient blood flow in right coronary arteries with varying curvature and side-branch bifurcation angles. Comput Biol Med. 2015;64:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misagh Imani S, Goudarzi AM, Valipour P, Barzegar M, Mahdinejad J, Ghasemi SE. Application of finite element method to comparing the NIR stent with the multi-link stent for narrowings in coronary arteries. Acta Mech Solida Sin. 2015;28(5):605–612. doi: 10.1016/S0894-9166(15)30053-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittal R, Seo JH, Vedula V, Choi YJ, Liu H, Howie Huang H, Jain S, Younes L, Abraham T, George RT. Computational modeling of cardiac hemodynamics: Current status and future outlook. J Comput Phys. 2016;305:1065–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2015.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apostolidis AJ, Moyer AP, Beris AN. Non-Newtonian effects in blood flow simulations of coronary arterial flow. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2016;233(1):155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2016.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirola S, Cheng Z, Jarral OA, O'Regan DP, Pepper JR, Athanasiou T, Xu XY. On the choice of outlet boundary conditions for patient-specific analysis of aortic flow using computational fluid dynamics. J Biomech. 2017;60:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nardi A, Avrahami I. Approaches for treatment of aortic arch aneurysm, a numerical study. J Biomech. 2017;50:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doutel E, Carneiro J, Campos JBLM, Miranda JM. Experimental and numerical methodology to analyze flows in a coronary bifurcation. Eur J Mech B Fluids. 2018;67:341–356. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechflu.2017.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]