Abstract

Purpose

Methods for delivering aftercare to help chronic pain patients to continue practice self-management skills after rehabilitation are needed. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) has the potential to partly fill this gap given its accessibility and emphasis on self-care. Methods for engaging and motivating patients to persist throughout the full length of treatment are needed. The aim of this study was to describe how chronic pain patients work in an ICBT program, through their descriptions of what is important when they initiate behavior change in aftercare and their descriptions of what is important for ongoing practice of self-management skills in aftercare.

Patients and methods

Following a multimodal rehabilitation program, 29 chronic pain patients participated in a 20-week-long Internet-delivered aftercare program (ACP) based on acceptance-based cognitive behavioral therapy. Latent content analysis was made on 138 chapters of diary-like texts written by participants in aftercare.

Results

Attitudes regarding pain and body changed during ACP, as did attitudes toward self and the future for some participants. How participants practiced self-management skills was influenced by how they expressed motivation behind treatment goals. Whether they practiced acceptance strategies influenced their continuous self-management practice. Defusion techniques seemed to be helpful in the process of goal setting. Mindfulness strategies seemed to be helpful when setbacks occurred.

Conclusion

Self-motivating goals are described as important both to initiate and in the ongoing practice of self-management skills. Experiencing a helpful effect of acceptance strategies seems to encourage participants to handle obstacles in new ways and to persist throughout treatment. Research on whether tailored therapist guidance might be helpful in stating self-motivating goals and contribute to ongoing practice of self-management skills is needed.

Keywords: Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy, chronic pain, acceptance and commitment therapy, qualitative analysis, self-management

Introduction

Effective and evidence-based treatments for chronic pain include multidisciplinary/multimodal rehabilitation programs (MMRPs),1 with components from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)2 or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).3,4 However, 30%–60% of patients have been estimated to relapse in some form after completion of traditional face-to-face pain rehabilitation,5 although the variation in relapse rates are wide.6 Relapse can attribute to a number of different factors, for example, increase in pain itself, medication use, sick-leave compensation, and perceived disability and quality of life. Relapse prevention has been described as a neglected area in face-to-face rehabilitation.7,8 A central part of relapse prevention after MMRP is helping patients to continue practicing their learnt self-management skills.9 Poor adherence to self-management strategies lower its effectiveness at follow-up.10,11 Meanwhile, improvements in depression, pain, and disability have been found to be related to ongoing practice of skills learnt in MMRPs.12,13

Research regarding what might help clinicians tailor rehabilitation interventions to the needs of particular patients has been called for.14 Also, the working mechanisms behind pain rehabilitation need to be further explored.9,15 Research on long-term psychosocial impact after treatment is limited,16 and strategies dealing with relapse problems after MMRPs are therefore needed.8,17

In line with the results of face-to-face trials of MMRPs, Internet-delivered CBT (ICBT) for chronic pain has shown small to moderate effects.14 The advantages of using the Internet as a platform for interventions, such as accessibility in terms of time and place,18 diminish some known obstacles, for example, physical disabilities, competing work hours, and geographical distances.19 Furthermore, isolated groups can be reached, and health service costs can be reduced.14 Also, client preferences show that some prefer online treatment and that it might reduce stigma and thresholds to seek treatment.20 Although ICBT is a feasible format for providing pain treatment, issues remain. Patients’ engagement in treatment vary across studies,21 for example, in terms of motivation and adherence to treatment assignments,22 and dropout rates are sometimes high.14

Chronic pain is often a life-long condition requiring lifestyle changes.23 Gains of MMRPs and other related interventions need to be sufficiently self-reinforcing for patients to stay engaged in life-long self-management.17 In rehabilitation and psychosocial treatments for conditions where remissions are common, aftercare plays an essential role. Combined with traditional aftercare, telemedicine and online services have the potential to prolong treatment effects, reduce admission, and improve outcomes including lower utilization of health care, for references see.24 Considering the need for relapse prevention, ICBT might be a suitable way to deliver aftercare following MMRP for chronic pain patients.17,18,25

One approach to refine chronic pain treatment is qualitative studies on patients’ experiences16 and self-management strategies.26 Qualitative studies may contribute to user-centered designs and solutions, which have been asked for in the development of Internet-delivered interventions.19

Education, explanation of the condition, and group activities are factors important for adherence and engagement in treatments according to qualitative analysis.16 Readiness to change, involving family members in treatment, feelings of control over the treatment process, and self-efficacy also seem to influence self-management.16 Increasing self-efficacy – a person’s perception of his/her ability to perform on a task27 – can predict behavior change.28 Also, engagement in treatment and adherence to intersession homework assignments are regarded as essential.29

Individual differences and mechanistic factors relating to how patients manage their pain – as pain-related psychological flexibility and catastrophizing – need to be considered to match the treatment with patient characteristics.17,30 Psychological flexibility, acceptance, and catastrophizing are examples of working mechanisms in pain treatment. Early changes in these domains predict outcome changes later in treatment.30–32 Moreover, an acceptance approach seems to be associated with more frequent use of relapse prevention strategies.33

Increasing ongoing motivational factors have been suggested to enhance persistence to engage in ICBT.34 Adherence to treatment has been shown to mediate the effect of readiness to change on outcome, specifically goal attainment.35 In motivational interviewing,36 five stages illustrate patients’ readiness to change: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. A pain patient’s readiness for change may be conceptualized as either in pre-complementation or in an action stage, whereas patients in the later stage may benefit more from treatment.37 Readiness to adopt to a self-management approach to chronic pain may be a predictor to therapy process mechanisms and important in promoting motivation and readiness to change.35

Although, even when patients adhere well during treatments as MMRP, they may not continue to self-manage their pain after treatment has ended.38 To premeditate patients who will deviate might be a plausible way. Providing additional sessions to remind patients of the importance of ongoing self-management might be helpful. Also, teaching patients how to apply self-management strategies when pain reoccurs or worsens might be necessary and important for patients’ self-efficacy.

The aim of this qualitative study was to describe how chronic pain patients (from now on called participants) work with an Internet-delivered acceptance-based CBT aftercare program (ACP). Our research questions were: 1) What do participants describe as important when initiating behavior change in aftercare? 2) What do participants describe as important for the ongoing practice of self-management skills in aftercare?

Patients and methods

MMRP for chronic pain

Before inclusion, participants completed an 8-week-long MMRP at a pain rehabilitation centre.1 The MMRP comprised group sessions with physiotherapist, psychologist, and occupational therapist and lectures in pain management and other aspects of health behavior. Individual sessions were available upon request, although the main part of rehabilitation was delivered in group format, wherefore patients’ homework in between sessions and individual commitment to rehabilitation were emphasized. Psychological elements in the MMRP consisted of eight group sessions of acceptance-based CBT and two seminars;1 group sessions covered the central components in ACT39 and CBT.

Internet-delivered ACP after MMRP

During an inclusion time of 24 months, all patients who had completed the standard group-based MMRP were invited to participate in a 20-week online self-help program with some therapist guidance, from now on called ACP, with the purpose to maintain gains and promote the ongoing self-management skill practice, to test the applicability of ICBT for chronic pain patients in aftercare. The provided Internet-delivered treatment resembled a self-help book, based on CBT, focusing on values-based behavioral activation,40 with treatment components also from motivational interviewing36 and ACT.41

The ACP consisted of eight modules (Table 1), delivered once a week, except for module 5, which comprised an assignment to be done repeatedly by participants independently during several weeks.

Table 1.

Overview of content, interventions, and focus in treatment chapter by chapter

| Modules | Treatment chapter | Interventions | Treatment focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to treatment | Educational information regarding aftercare program and website | Adherence, self-efficacy, informed consent, therapeutic alliance |

| 2 | Valued directions | Elicit and formulate valued life directions | Exposure to fears and losses |

| 3 | Aftercare plan | Guide decision-making Acknowledge skills and abilities |

Problem-solving Acting for long-term consequences Perspective taking |

| 4 | Introduction to Bull’s eye exercise | Values-based behavioral activation | Behavioral activation |

| 5 | Continuous individual work with Bull’s eye exercise Occupational therapist worksheets and physiotherapist worksheets available and delivered by e-therapist based upon individual needs |

My choice Committed actions training Promoting willingness Doing what is important |

Exposure to fears and losses Broaden behavioral repertoire New experiences from pain-eliciting activities Experiencing overcoming obstacles |

| 6 | Summary and conclusions | Story of self Enhancing self-reinforcement |

Promoting readiness for future obstacles Enhancing self-efficacy |

| 7 | Evaluation | Declare neglected needs and highlight difficulties | Assertiveness Willingness |

| 8 | Self-management plan for the future | A courageous stance Acknowledge gains Choose goals Self-reinforcement |

Establish rule-governed behavior in valued life directions Maintain treatment gains |

The modules of the ACP consisted mainly of text and worksheets based on selected parts of the psychology group sessions in the MMRP. Additional worksheets containing repetition from physiotherapy sessions and occupational therapy sessions were available. In these fixed worksheets, it was yet open for the participants to state their own goals with treatment. Participants’ free choice resulted in a wide range of goals, covering for example relationships, work, health behavior, and self-fulfillment. Participants were given extensive online feedback from a pain psychologist (from now on called e-therapist) during the first four modules, and then continued working more independently during the latter four modules, unless they asked their e-therapist for feedback. E-therapist feedback consisted of on average 618 words per participant (ranging from 53 to 1185). The function of the e-therapist feedback was all through the ACP to enhance self-efficacy, for example, by acknowledging helpful behaviors and skills or highlighting the planning that led to the participants’ goals.20 The participants and the two e-therapists knew each other from the MMRP. In addition, a consulting team consisting of a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, and a pain-specialist physician were available if necessary. Treatment content and focus are schematically presented in Table 1.

The overall treatment focus of the ACP was to help participants act in their valued life directions rather than focus on diminishing pain. This was done in three steps: First, following the introductory and goal-setting modules 1–3, the main part of treatment, covering modules 4 and 5, aimed to give participants new experiences of acting in the presence of pain in order to broaden their repertoire of behaviors in activities often associated with eliciting more pain. In doing so, they were encouraged to weekly evaluate their actions with regard to how much in line with their chosen value they had acted, using a rudimentary version of Bull’s eye values survey.42 This aimed to help them focus on behavior change rather than symptom reduction and also to promote self-efficacy by acknowledging self-care behavior. Second, in module 6, the participants summarized how they had acted to reach their goals and how they had handled obstacles during the ACP. This aimed to promote readiness for future obstacles and also to enhance their self-efficacy.

Finally, the last treatment module aimed to help patients make long-term values-driven goals and to build a foundation for continuous self-reinforcement. Additional treatment elements such as assertiveness training, guided problem solving, and exposure to losses are presented in Table 1.

Participants

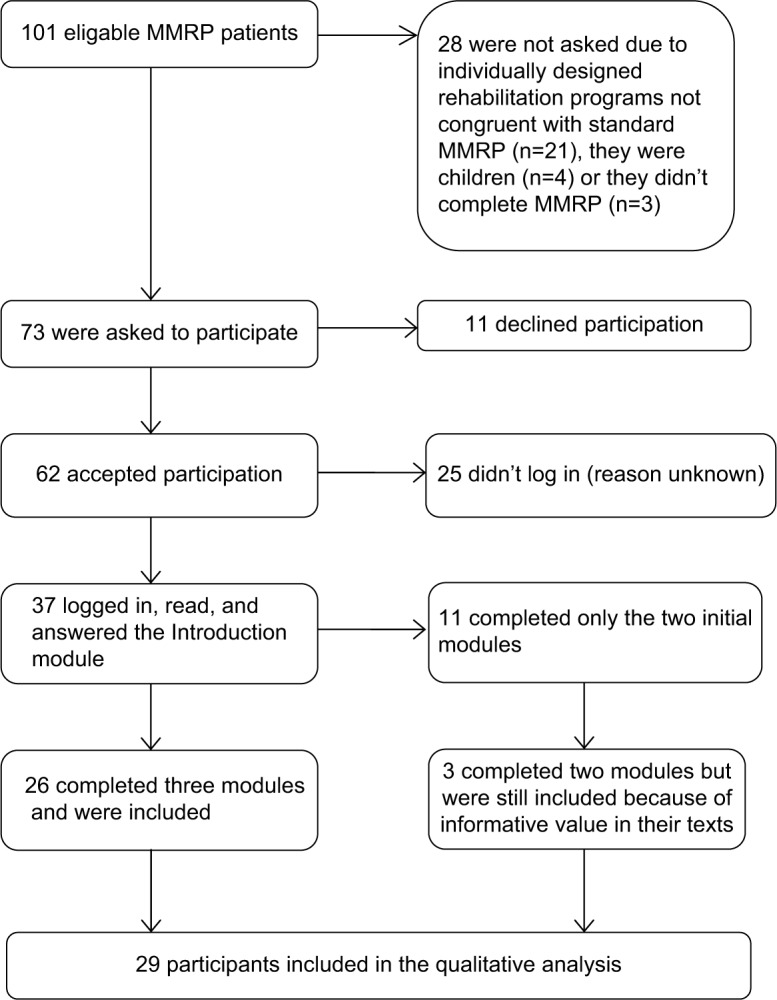

Inclusion criteria for patients were: 1) completed premeasurement scores prior to start of MMRP, 2) completing MMRP, 3) access to computer and the Internet, and 4) completion of the first three modules. Out of 101 eligible participants who completed the MMRP during the inclusion time, 73 were invited (Figure 1). Of the 61 who reported an interest, 37 logged in and started working with the program. Twenty-six participants completed at least three modules and therefore completed the most important treatment parts in terms of aftercare.43 Another three participants completed only two modules; however, since their text had a highly informative value, they were included in the qualitative analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion procedure.

Abbreviation: MMRP, multimodal rehabilitation program.

Participants were mainly females (26 of 29). Mean age was 37 years (spanning from 22 to 53 years). Mean time of pain duration was 6 years (spanning from 1 to 21 years). Thirty-four percent of participants were working to some extent, while 41% were on full-time sick leave. The remaining was either in the process of applying for jobs, studying, or had municipal support. Sixty-nine percent of participants had a high school education and 17% had college/university education.

Of the participants who did not complete all eight modules, reasons for attrition were unknown for the largest part (10 participants). Five participants declined in participation as they started vocational training and another two because they prioritized competing life events, for example, focused on studies. Four participants dropped out because of the onset of new illnesses or symptoms. Two participants dropped out because of technical problems and another two said that more guidance might have helped them to comply (see the “Data availability” section).

Data collection

The qualitative analysis was based upon contributions from 29 participants. Participants completed on average five modules each (ranging from 2 to 8), resulting in 138 chapters of written text (all together 50,999 words) to be included in the qualitative analysis. Participants produced on average 1759 words (ranging from 191 to 6842). Since the aim of the study was to understand what the important factors for participants are, while being in aftercare, all written materials that could have an informative value were included. An advantage of using participants’ own written text instead of interviews is that their experiences are less affected by memory loss as a consequence of time passed post treatment. The texts they had written in the worksheets could be viewed as a sort of diary notes, which provides a detailed picture of their feelings, thoughts, fears, and strains at the time. A disadvantage of not doing interviews is that participants cannot explain, frame, or further develop their notes and no further questions can be proposed to them. However, the latter three worksheets (Summary and conclusions, Evaluation, and Future plan for self-management) were written at the very end of ACP and had a slightly different focus than the previous ones. Participants then evaluated their own work and were encouraged to go back and read what they had previously stated as goals to compare with their perceived gains. Hence, reflections made by them in these evaluations to some extent compensated for the loss of their own reflections that an interview could have provided. An important ethical advantage of doing a qualitative analysis based upon already written text is that a rich material is available without having to disturb participants further.

Data analysis

ACPs are multifaceted treatments, as are MMRPs, since it is difficult to state in an early stage which combination of interventions will help a particular patient. As this study focused on participants’ views and perspectives44 on what is important when initiating behaviour change as well as when continuing to practice self-management skills during aftercare, a qualitative approach was regarded as a plausible way to generate new ideas on how to deliver an ACP, in line with what influences motivation and affects the ongoing practice of self-care.

As units of analysis, the diary-like texts of the participants provided a description of an ongoing process,45 and therefore, an in-depth exploration as latent content analysis46 was chosen to show the underlying meanings relating to change and motivation. As patients with chronic pain often have comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions, an advantage of a qualitative approach is that these contextual factors add further meaning and credibility to the material rather than being a hindrance for comparisons. Using content analysis of participants’ notes, it was our intention to capture participants’ in-moment perceptions as well as retrospective thoughts, relating to motivation and behaviour change.

Analysis process

When analyzing the texts by using Open Code 3.1,47 quotes were selected as meaning units if relevant to two areas of interest, coming from the research questions: 1) what is described as important for initiating behavior change? and 2) what is described as important for the ongoing practice of self-management skills? A third area of interest was considered during this stage: 3) how do participants, at end of the ACP, describe behavior change? These content areas were the frameworks in the beginning of the analysis to prevent drift and ensure dependability. The text was initially sorted into these three content areas, but during the analysis process, meaning units were found across content areas. The quotations were shortened into condensed meaning units and meanwhile coded. Codes were then abstracted into individual categories specific for each of the 29 participants. When moving from condensed meaning units and codes to individual categories, latent content was collected to understand the underlying meanings in individuals’ descriptions, although kept separately from the manifest content forming the individual categories. All individual categories were then conceptualized in group categories based on similarity. For example, from the question “What do participants describe as important when initiating behavior change?” the text from one participant resulted in coded units that were sorted into five individual categories (Table 2). Together with individual categories from other participants, they were sorted into group categories.

Table 2.

Example of the coding process

| Content area | Condensed meaning unit | Individual category | Group category |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is described as important when initiating behavior change? | “React in a way that is my own” “Be involved in what I do” “I want so much but my body can’t handle it” “I’m afraid of setting goals” “Manage myself”, “Maximize my chances to succeed” “Others can’t help me with this, it’s rather within me the change needs to occur” “Dare put myself in new and unknown situations” |

Want to act as myself (with honesty) Want to be involved Frustration and fear connected to dreams Enhance independence Change needs to occur with me, take command of my situation |

My time now Longing for work and participation Skepticism/uncertainty Overcoming/evolving |

A psychologist evaluated the initial coding process to ensure credibility in terms of a clear line from transcript to individual categories, with the aim in mind. The psychologist had experience from pain rehabilitation, although he did not know the participants, or had knowledge of the content of the specific MMRP and ACP. In the process of conceptualizing group categories, these were presented at a seminar with experienced pain rehabilitation researchers to be evaluated in terms of credibility and informative value. Finally, all group categories were viewed together in search for general recurrent themes cutting across categories. Six themes were found based on a time perspective, including latent content relating to change; in the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. To reveal the meaning units that contradicted the themes, they were sorted under the six themes, to fit in the beginning, middle, or end of treatment. In doing so, differences among participants were revealed relating to motivational processes and therapeutic strategies used.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Research Committee in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr: 2010/186-31). All participants gave verbal informed consent to participation prior to inclusion and an electronically written informed consent as they logged in to the website.

Results

A model of self-management practice

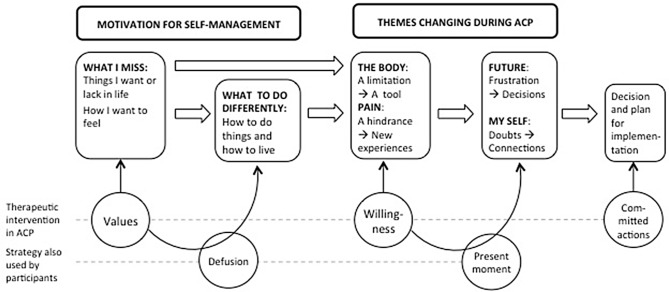

Data analysis produced six themes relevant for participants’ change. Four of them reflected changes in attitudes during ACP, namely the body (1), pain/pain-related symptoms (2), future (3), and my-self (4). Within these four themes, different aspects were emphasized in the beginning, during, and by end of the ACP.

Another two themes produced represented aspects that influenced participants’ skill practice, namely motivation (5) and therapeutic intervention (6). There were similarities and differences among participants in what aspects of motivation and therapeutic interventions that were emphasized in their texts. The results – including central themes, aspects of motivation, and used therapeutic interventions – are schematically summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of result: central themes, aspects of motivation, and used therapeutic interventions.

Abbreviation: ACP, aftercare program.

Body and pain/pain-related symptoms

Participants’ view of their body and their perception of pain and pain-related symptoms (tiredness, anxiety, depression, and obesity) were described in different ways during the course of the ACP. When writing about their body in the beginning, participants described it as somewhat of a necessity for change in other areas, a limitation and/or something they need to deal with.

I want to exercise my body and become physically more and more active, so that I can manage work, family and have fun on my spare-time. [Participant 5]

Throughout the program, a different view on their body emerged; described as a tool or a key for change, something usable and something worth investing in and worth nursing.

Tend to my body to get more energy. […] I’m losing weight and I’m feeling that my body has more energy and strength. […] I believe that if I become more physical and work my muscles, there might be more to take from when I get pain. [Participant 19]

By the end, a shift had occurred in the way participants commented on their body. They were aware of it, noticed its presence and saw it as something that reminded them to use strategies.

Balance how much strength I put in and how much I manage. See my limitations. […] I’ve felt good just being. I’ve managed my working postures without stiffness and pain. […] I’m pleased with my week, I’m especially happy for pulling through what I intended, that I’ve felt fresh in the morning and that I didn’t end up stiff and in pain. Things work out for me. I’m happy with my life. […] I won’t neglect my abs practice, it made my pelvis hurt. […] Slow down at work, take breaks, go for walks. Walk every day. Balance. Accept I don’t have energy for everything. [Participant 13]

As with their attitude toward their body, participants also described a change of view in their perception of pain and pain-related symptoms. In the earliest phase, pain and pain-related symptoms were described as something participants needed to get pass, a problem they had to take on, something that must be focused upon, mentioning that “now is the time for change.”

Make sure I get out for walks a few times a week even though I’m working. […] I must focus on exercising if I want to keep losing weight, so therefore I have to do it. […] I want to feel pretty and be comfortable with myself and like myself. I also hope that pain will be a little less if I don’t put extra load on it. So, I put my hopes into enduring all these weeks so that I can look the way I wish. […] Don’t remember last time I did so now’s really the time to do something about it. [Participant 20]

During the ACP, participants’ perception of pain as an obstacle seem to have shifted toward pain being perceived as one piece of several in their self-care plan, which is a potential hindrance, although not their main focus. When pain did become a hindrance, participants held on persistently to their plan and focused repeatedly on what they intended to do. Pain and other related problems they initially struggled with were not seen as a reason to stop, but rather as a call to fiercely maintain their commitments.

Do it anyway, do some or take a walk instead so that I at least move around some. [Participant 10]

When participants retrospectively summarize their actions during the ACP, they expressed new experiences from moments where they had encountered pain and gained progress by being persistent rather than backing down when pain and other problems had emerged.

I haven’t succeeded in finding a solution for my sleep but rather accepted it the way it is. That made me let go of the frustration and anger with my sleep, which is rather nice to lose. I keep looking for and trying out new solutions to the problem, but I’m feeling I’m not doing it as desperately as before. [Participant 28]

When pain keeps increasing and fights with me, I will hold a positive attitude and try out new ways and ask for help. [Participant 9]

This illustrates a perspective shift turning away from viewing body and pain as a constant hindrance, toward focusing on other things in life. Gradually they described their body as an aid for executing plans and pain as one potential hindrance. This resulted in a more positive, confident, curious, or open attitude. They also focused more on what was possible to do when making plans, rather than acting because of frustration, sadness, or disappointment. Experiences of gains and overcoming obstacles seemed to be consistent with acting persistent and not being broken down by a setback.

View of future and description of self

Some participants described a growing new perspective on what the future might bring and on their view of self. Hence, in the beginning, participants wrote about longing, lacking, and frustration. They questioned what suited them in terms of jobs, exercises, and social relations.

To feel joy about my life, more faith in the future. […] I don’t want to feel low which I do in bad days/times. I want to feel I can make plans without fearing I’ll get PAIN then. [Participant 8]

During the ACP, participants’ concerns about the future were visible in their planning and day-to-day work with reoccurring problem solving where long-term consequences were taken under consideration. Meanwhile, they to a large extent focused on taking small steps of change in their everyday life, and they liked what they did there and then to what they expected would come out of it eventually. This perspective seemed to motivate them to be consistent in practicing self-management skills, wishing that their pulled effort would reward itself later on.

Might start at my trainee position next week. Feels like an extremely tough and big step to take right now. […] Boss said to take things my own pace and only do as much as I know and can. She said I’m there for my sake, to see if working is possible. Feels exciting. As long as I don’t strive too high. [Participant 21]

At end of the program, one significant aspect of participants’ views of the future was expressions of life decisions. Some declared monumental decisions impossible to knock over and some concretized anticipations. One participant wrote that she had raised the bar for what to expect out of life. Another participant stated that she’s not waiting anymore for her life to start.

I think I’m heading in the right direction […] for sure, but I’m not yet all the way there, I’m thinking it will take time. Although I’m definitely on the go. I believe it shows. […] I’m getting forward, I’m on the right track, I’m trying to live my life ☺. [Participant 2]

In the beginning of the ACP, participants’ views of themselves were characterized by expressions of loneliness, confusion regarding how to get a hold of their life, and also a will to revenge oneself in life.

Work is such a great part of your life, but it can’t drain all your energy. Then life becomes “poor.” Can I do nothing but work, eat and sleep, I’ll turn into a bitch, no fun for anyone, least at all myself! [Participant 4]

During the ACP, some participants expressed improved assertiveness skills. They started acting in their interests, stating their needs and wants, declaring their own responsibility and tried new ways to state their own opinion. They encouraged themselves with statements as “carpe diem!” [Participant 5], “pull myself together” [Participant 12], and “this is my race” [Participant 16]. Honestly they declared truths about themselves as “[…] show some interest in my friends’ lives and problems. Frankly, become a better friend” [Participant 3].

I’ve learned to take it easy when I’m worse not to hurt myself in other ways. When I’m feeling worse, I need to inform those around me to avoid controversies. I’ll keep a diary every day to monitor my activity level. Make time for myself. Decline if there’s something I can’t handle. Stay to it. It will calm down soon. Think it over and do something that gives me energy back. Say yes when opportunities come along. Seize opportunities and give suggestions. Ask for help even with small things. [Participant 29]

Looking back on efforts made, some described changes relating to themselves. Some perceived a different view on their situation, where unresolved problems did not bother them in the same way, by using descriptions such as “a larger perspective” or “a new focus in life.” They praised themselves, showed pride, and mentioned self-confidence.

When I confronted what were “frightening” and noticed I could deal with it, with my lower demands, I let go of many barriers. Trying all this, was an intense period and I was so tired I completely stopped bothering about what was happening or what people thought of me. I learned it’s all right to do/say wrongly sometimes. Now I’m getting closer to recognizing it’s okay to show how you really are/feel. I’m more comfortable with myself. [Participant 28]

Concerning the way participants wrote about themselves and the future, this seemed to influence their readiness to move on after the ACP. When describing a willingness to recognize their experiences of pain, also such they had previously repulsed, a shift in perspective of self emerged. Also, writing about a readiness for facing the uncertainty of the future seemed to facilitate making life decisions of longstanding commitments.

Motivation

Declarations of goals and motives were partly guided by the structure of the ACP. Still, there were differences among participants in terms of how they phrased their motives and what they expected to change. Initially, all of them described things they missed, lacked, and longed for. Some also described how they dreamed their lives would be like and what they wanted to do differently. They used expressions as “being at the end of the road,” “enough is enough,” and “turn a leaf.”

I want to remember how it feels like to be tired in my muscles […] and long for the next time. [Participant 26]

In their weekly attempts to reach their goals during the main part of the ACP, some were motivated by encouragement from others. Meanwhile, acknowledging the progress they had made motivated others. During this time, setbacks occurred. Participants’ plans were disrupted or found to be malfunctioning. They mention disappointments over knocked-over plans. Differences among participants then became evident. Some participants encouraged themselves by using setback experiences to clarify another round why they needed to change. A setback was not merely seen as a failure, rather as a reminder of the importance of keeping up the steam and keeping focused in their work. Setbacks were also viewed as reminders of what they longed for and their own responsibility to take action to move toward that.

Think about why I’m doing this. Write it down so I’ll see it every day. […] Tell someone what I’ve done well by the end of the day. [Participant 29]

Participants, who found ways to meet misfortunes with an optimistic view, distinguished themselves when describing their motivation to ongoing self-management skill practice after the end of ACP. Besides being motivated by what they missed, they wanted to change how to do things and how to live. This was visible already in the beginning of the ACP when they not merely described the feelings they lacked but also how they wanted their lives to be like. They used expressions such as “hold on,” “even though,” and “no matter what.”

Carrots in front of me – when one’s eaten I want to see the next a bit further. [Participant 9]

I can change everything at once as long as I want to!!! [Participant 20]

It’s worth being troublesome to get what I want! [Participant 28]

When life is back. [Participant 13]

Being able to see a setback as a useful experience might have been important for their perception of their ability to handle obstacles later. Also, motivating yourself not only out of feelings you long for but also by how you want to take on life seemed to be important for maintaining the spirit even through times of misfortunes, as described by this participant:

I enjoy being the cheerful soul among people around me – I like to make people laugh and have a good time, it gives me a pleasant kick. I want to be happy and I am when I laugh joyful and have a good meal with my wife, my family and close friends. When I’m feeling well, I can be there for them and help them when they need me as they are there for me when I need them. I want to give back what they give me now, right now it feels as if I’m mostly the one who’s receiving. I want that balance back. […] Life goes on right now and I want to enjoy it now, not later on. [Participant 2]

Therapeutic interventions

The three main treatment components participants were expected to use (values elaboration, acting with willingness, and making committed actions) were explicitly described in participants’ texts. Another two treatment strategies, familiar to patients from the MMRP, although not targeted in the ACP (defusion techniques and present moment strategies) were also described. These methods were used at different time points. When elaborating and declaring valued directions in life, some patients took use of defusion techniques (a perspective of cognitive distance to thoughts, emotions, and sensations). Likewise, when working with the reoccurring willingness exercise during the middle of the treatment, some patients used present moment strategies. By the end of the treatment, participants made decisions and plans for the future, by using committed actions, in line with treatment protocol.

In the beginning, participants are encouraged to consider what matters in life, by using value elaboration to formulate treatment goals.

I want to be able to go to work and feel joy and anticipation for my day. Want to feel occupational pride and take pleasure in my work again. [Participant 4]

Some declared valued life directions with a distanced attitude to thoughts. They took a step back and viewed their situation from a different angle before deciding on treatment goals. This might have been a consequence of previously learned defusion strategies.

I miss having patience to sit down and talk to my husband without simultaneously thinking about what to do next and worrying about things that have already happened. [Participant 18]

During the middle of the ACP, the participants wrote about their day-to-day experiences of managing their pain. While describing actions toward their goals, they expressed willingness to what is difficult in their lives.

Talk to my partner or someone else close to me about how I’m feeling (glad, sad, angry, irritated – you name it). Won’t hold it to myself anymore or hide my feelings, rather show it and talk about it to make me feel better and get a perspective on life and my emotions, which sometimes runs riot. [Participant 2]

Present moment strategies were used in different ways to make changes with feelings, thoughts, and sensations in mind. Being in the present moment seemed to be helpful when approaching difficult situations.

Start everything I do in a relaxed state. Take a few deep breaths. Think this is what I’m doing right now. [Participant 23]

By the end, participants wrote about value-based commitment actions to guide them in the long run. Some used metaphors, for example, this participant who recognized her behavior pattern of being highly energetic wishing to focus her energy on the things that matters to her.

Think about what’s running that Duracell Bunny and chase it in the right direction. [Participant 29]

It seems like defusion techniques were helpful for participants when making their values directive in the early stage of treatment. In the middle of the treatment, mindfulness strategies seemed to help with acting with willingness. At end of the treatment, participants made longstanding commitments for the future. In this process, there were descriptions where participants viewed themselves and their situation in light of previous life experiences. This shift in perspective seemed to be helpful when making decisions about their attitude toward what is difficult in life and not merely trying to change what is difficult.

I won’t bother myself and I don’t want to be bothered by people’s opinion of what to do or what not to do because something’s better than the other etc etc. I will do what I want, what’s good for me and it’s up to them to handle that, they can have their own opinion and if this doesn’t suit them I can be without them. I want to live my life as I want to and in the way that’s best for me (and my partner). [Participant 2]

I want to be able to see the beauty of it. [Participant 17]

The following quote is from a participant describing what motivated her to ongoing self-management skill practice.

To truly deep inside believe that I’ve really done something well when someone tells me so or realize that others might appreciate something even though I’m not content. To admit to myself that I’ve done something well and not merely focus on the row of mistakes and errors I could have avoided to get a better result. To dare be sad in front of others without acting as a clown at the circus. [Participant 29]

Discussion

Changes in pain catastrophizing and psychological flexibility early in treatment have been found to predict outcome later in treatment.31 This study suggests that using defusion techniques is helpful when expressing life values in an attempt to reach change in life (illustrated in Figure 2). The study also suggests that personally relevant goals and defining the motivation to change are important for practicing self-management skills. Previous findings suggest that it is successful to structure an ACP based on what motivates patients, when the aim is to enhance self-management.29 Beginning with areas of concern for the patient may promote feelings of control16 and relevance of treatment29 and make way for an early change in pain catastrophizing and psychological flexibility.32 Pain-related psychological flexibility and cata-strophizing should be monitored in order to understand how interventions can be tailored after patients’ needs.30 Our findings suggest that experiencing a helpful effect of practicing willingness strategies early in ACP might be important for practicing self-management skills and may result in a positive attitude toward the future.

Discussion of the results

Self-motivating goals

Goal setting is commonly placed in the beginning of the treatment, to draw a direction and to enable therapist and client to tell when goals are met, and treatment should be completed. When chronic pain patients state goals, dreams, or values, they might end up with a blank sheet, goals that spring from what they ought to do, or goals striving to regain what they have lost. Clarifying long-term goals by the end of MMRP might seem contra intuitive but may be strategically successful if these goals are stated in a willing and present state of mind. Our results suggest that goals focusing not only on what participants wish to achieve but also on how they want to live might have contributed to consistent practicing of self-management skills. Defusion techniques helped some participants to state goals in terms of how to live to make way for what they long for. Hence, defusion techniques might be considered important in the goal-setting process of ACP.

Patient characteristics in terms of behaviors, feelings, and beliefs need to be focused upon in relapse prevention.17 The present results suggest that structuring ACP to start with a problem or symptom where a patient expresses strong motivation to change can help motivate patients to stay consistent in practicing self-management skills. Most participants experienced a shift in perspective upon their pain and its effect on life. Some also experienced a perspective change in self and future. Such a shift seemed to have facilitated making longstanding decisions concerning self-management by the end of ACP.

Gains from pain rehabilitation need to be sufficiently self-reinforcing for patients to stay engaged in life-long self-management.17 When participants reached a goal, it was described as a success. However, they also used descriptions as success and gain when they noticed that their plan was working. One possible interpretation is that gains become self-reinforcing when patients link their everyday behavior to their desired goal.

Acceptance strategies and adherence

It has been claimed that readiness to adopt to a self-management approach may be important for motivation and readiness to change.35 Also, greater benefits from treatment are to be expected if a patient is in an action stage rather than in a pre-complementation stage.37 To reduce attrition, it is desirable with early identification of participants with difficulties to adhere. The present results suggest that the use of acceptance strategies and self-motivating goals might be cues to whether a patient is ready to adapt to a self-management approach.

Acceptance-oriented self-statements are associated with using relapse prevention strategies and possibly facilitating change.33 These results suggest that participants who experience a helpful effect of practicing willingness strategies are helped through setbacks during ACP. One possible interpretation of the findings is that readiness to change could be elicited by helpful experiences of handling obstacles with an acceptance attitude. If so, therapist guidance focusing on helping patients to act with willingness early in treatment might be a plausible way to make patients ready for change.

Tailored e-therapist guidance

People can learn how to act with willingness with a minimum of therapist support.22 Guidance on the sufficient level of therapist support in ICBT has been called for17,19,22 to optimize adherence and outcomes. A cutoff in minutes of therapist–patient contact to prevent dropouts has been discussed.18 The present ACP differs somewhat from earlier ICBTs for chronic pain, since therapist support was primarily given in the beginning of ACP and later on reduced to a minimum. Self-efficacy16 has been suggested to influence self-management. When an e-therapist gives feedback on which participants’ actions precede improvements, it might help patients to self-evaluate their work and raise self-efficacy. However, more is yet to learn about e-therapist support in general and indication for further support in particular. Participants in this study were given additional support upon request. Decrease in treatment engagement as well as unexpressed motivation might be another two indicators for providing extra therapist support.

The second research question addresses what influences continuous practice of self-management skills. Setbacks are to be expected in aftercare. Some participants in the present study seemed to stay persistent in practicing self-management skills despite setbacks by handling recurrent obstacles in new ways, by using acceptance strategies. Also, present moment strategies seemed to make it easier to be in contact with experiences associated with setbacks and disappointments. If an e-therapist helps participants to summarize willingness and mindfulness skills, this might make it easier to apply these later on when setbacks occur. A setback then becomes an opportunity for patients to test their self-management skills.

Methodological aspects

As a pilot study on the development of an Internet-delivered ACP, open for all interested eligible patients, the explorative design of the present study included almost all materials available. Besides text written by those who completed the treatment, contributions from another three persons (participants 3, 4, and 15) were included since descriptions of how behavior change was initiated were found in their materials. Experienced colleagues gave feedback during the analysis process to ensure validity and openness. The detailed description of the analysis process aims to enhance openness about assumptions and consideration made. A multi-professional consulting team aided with medical guidance and ethical considerations when unexpected changes in participants’ symptoms occurred during the ACP. Some personal information has been changed in the quotes, not to expose participants or reveal their private details.

The participants had been referred to a multidisciplinary pain center at a university hospital, and their mean time of pain duration spanned from 1 to 21 years (mean 6 years). Seventeen percent of them had a college education, and 41% had full-time sick leave compensation. Since participants were recruited directly from an MMRP, some thresholds might have been reduced, making it easier for patients who ordinarily would not seek ICBT, to participate. A majority were women (90%), in line with the overrepresentation that is seen in MMRP (ie, >80%).1 There is a need in future studies to include more men. Whether this disproportionate representation is due to gender differences in pain prevalence or to a selection bias to MMRP is not known. Developing Internet-based treatments based on experiences of non-completers might help create pain rehabilitation and aftercare that suit the needs of underrepresented patient groups.

Feasibility of ICBT as aftercare

The relatively large initial interest in the ACP (62 of 73 participants, Figure 1) might illustrate that patients anticipate an ACP to fill a gap following an MMRP. A total of 37 participants then chose to engage. It is reasonable to assume that all MMRP attendees are not in need of additional care. Given the extensive variation in relapse after MMRPs5,8,12 it is possible that different kinds of relapse prevention are needed.

Inspired by previous findings,34 the present ACP aimed to simplify and individualize tasks to enhance persistence and completion. Participants were free to select treatment goals by their own choice and worked relatively independent with the program. This aimed to generate knowledge on what parts of treatment that were relevant for them in terms of initiating change and keeping work going over time. It was hoped that this setup would also enhance personal commitment to engage in treatment and keep motivation high over time. Our results do not confirm whether simplifying treatment does affect completion. Nor does it confirm whether withdrawal of the initial intense e-therapist guidance did influence participants’ motivation. Individualizing treatment goals and content might have had an effect on persistence since participants who were driven by personally motivating goals seemed to overcome obstacles easier and carried on longer in treatment. Based on the present findings, individualized goals might contribute to ACPs’ feasibility. Whether the simplified treatment tasks and reduced e-therapist contact effected feasibility cannot be concluded in this untailored format. A next step could be to study whether the nature of participants’ goals impact persistence in aftercare and sustained behavior change.

In this feasibility study, diary-like texts were analyzed in order to contribute with insights, new ideas, or emerging concepts that could explain or broaden our understanding of how self-management skills are maintained after MMRP. Analyzing participants already collected written text was a reasonably easy way to capture ideas of how skills were implemented in everyday life. Capturing participants’ spontaneous reflections of their own actions provided a rich material of day-to-day experiences. Interviews during and after MMRP would be of great value to deepen the understanding of what helps pain patients generalize self-management skills after MMRP. However, that would require that participants invested more time as well as more research resources. These participants produced a rich material (on average 1759 words, ranging from 191 to 6842). We suggest that the ACP might be feasible as a mean to set goals, evaluate a weekly progress and checking-in on a relapse prevention plan.

Attrition

Seven of the 26 participants withdrew from further participation mainly due to work-related factors. Reasonably pain patients have different needs of aftercare, in terms of format, content, and time. An ACP should help participants to implement self-management skills to enable them to take the next step in their rehabilitation plan. Some reasons for attrition might thereby be seen as anticipated and legitimate. However, only four participants did complete the finale module in the ACP. Non-completion might of course also indicate that the patient is no longer in need of treatment.

Taken into account the described changes illustrated in Figure 2, this study suggests that Internet-delivered aftercare might be a feasible format for helping pain patients to keep practicing learnt self-management skills after MMRP. However, to facilitate participation, more attention needs to be paid to make adjustments that fit the needs of those who find it difficult to independently practice self-management skills after MMRP. This group of participants might be found at an early stage by looking at how they state their goals in the beginning of the ACP. A next step could be to study whether the nature of the participants’ goals impact persistence in aftercare and sustained behavior change.

Some participants did not complete all eight modules. Lack of therapist support was mentioned as one reason for this. It is unknown whether additional therapist guidance would have increased adherence. It is possible that a more thorough examination of reasons for attrition would have generated ideas on how to promote adherence during aftercare. Interviews with participants who do not adhere might be an important next step for further development of ICBT.

Conclusion

Most participants described changes related to their body and pain. Experiences from physical activities gave them new perceptions of living with pain and discomfort. Some participants acted with awareness of their pain and adapted after previous setbacks. This brought on a larger perspective on their situation as well as confidence. The result also suggests that participants with self-motivating goals were more persistent in their self-management skills practice. Some participants showed a change in attitude toward the future and a shift in perspective on themselves. This seemed to be helpful when stating long-term goals.

This study suggests that self-motivating goals play a role in initiating and continuously practicing self-management skills. Using acceptance strategies might help participants to take on reoccurring obstacles in new ways. Therefore, acceptance strategies might be important to maintain practice of self-management skills.

Using the Internet as a base for psychological treatment programs have several benefits, for example, increased accessibility14 as well as facilitating participation when economic, time, or geographical reasons are hindering. MMRPs are designed to educate patients with the coping skills necessary to manage their pain. A need for aftercare might therefore be seen as a failure. Although, if it leads to more independence in the long run, we suggest that aftercare should be the next step in a sequential care setup. Considering the life-long process of self-managing chronic pain, ICBT might be a feasible format since it enables patients to continue their aftercare in their homes.

Data sharing statement

Detailed information on reasons for and time of attrition during the course of the ACP is available through the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Psychologist Jörgen Öberg for his contributions and expertise in CBT when developing and conducting the ACP.

This study was supported by grants from the County Council of Östergötland (forsknings-ALF) and AFA insurance. The sponsors of the study had no roles in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gerdle B, Molander P, Stenberg G, Stålnacke BM, Enthoven P. Weak outcome predictors of multimodal rehabilitation at one-year follow-up in patients with chronic pain – a practice based evidence study from two SQRP centres. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1346-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC. Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):59–63. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hann KEJ, McCracken LM. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with chronic pain: outcome domains, design quality, and efficacy. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2014;3(4):217–227. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turk DC, Rudy TE. Neglected topics in the treatment of chronic pain patients – relapse, noncompliance, and adherence enhancement. Pain. 1991;44(1):5–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90142-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, et al. Long-term outcomes from training in self-management of chronic pain in an elderly population: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2017;158(1):86–95. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogovor A, Visca R, Auger C, et al. Informing the development of an Internet-based chronic pain self-management program. Int J Med Inform. 2017;97:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morley S. Relapse prevention: still neglected after all these years. Pain. 2008;134(3):239–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandy M, Fogliati VJ, Terides MD, et al. Short message service prompts for skills practice in Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain – are they feasible and effective? Eur J Pain. 2016;20(8):1288–1298. doi: 10.1002/ejp.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EE, Foster NE. Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD005956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005956.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD000335. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Corbett M, et al. Is adherence to pain self-management strategies associated with improved pain, depression and disability in those with disabling chronic pain? Eur J Pain. 2012;16(1):93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Sharpe L, et al. Cognitive exposure versus avoidance in patients with chronic pain: adherence matters. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(3):424–437. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buhrman M, Gordh T, Andersson G. Internet interventions for chronic pain including headache: a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2016;4:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vowles KE, McCracken LM. Acceptance and values-based action in chronic pain: a study of treatment effectiveness and process. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(3):397–407. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin ZC, Smith NC, Fowler NE. A qualitative investigation of factors that matter to individuals in the pain management process. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(19):1934–1942. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1107782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skinner M, Wilson HD, Turk DC. Cognitive-behavioral perspective and cognitive-behavioral therapy for people with chronic pain: distinctions, outcomes, and innovations. J Cogn Psychother. 2012;26(2):93–113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson G. Using the Internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(3):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keogh E, Rosser BA, Eccleston C. E-Health and chronic pain management: current status and developments. Pain. 2010;151(1):18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersson G. The Internet and CBT: A Clinical Guide. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beatty L, Lambert S. A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(4):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Forder L, Jones F. Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(2):118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedberg F, Williams DA, Collinge W. Lifestyle-oriented non-pharmacological treatments for fibromyalgia: a clinical overview and applications with home-based technologies. J Pain Res. 2012;5:425–435. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S35199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loucas CE, Fairburn CG, Whittington C, Pennant ME, Stockton S, Kendall T. E-therapy in the treatment and prevention of eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen MP, Turk DC. Contributions of psychology to the understanding and treatment of people with chronic pain. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):105–118. doi: 10.1037/a0035641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore A, Jull G. Capitalising on effective treatment strategies for low back pain – How do we bridge the self-management gap? Man Ther. 2010;15(2):133–134. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122–147. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: an integrative model. Addict Behav. 1990;15(3):271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerns RD, Burns JW, Shulman M, et al. Can we improve cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic back pain treatment engagement and adherence? A controlled trial of tailored versus standard therapy. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):938–947. doi: 10.1037/a0034406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Fox JP, Schreurs KMG. Psychological flexibility and catastrophizing as associated change mechanisms during online acceptance & commitment therapy for chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 2015;74:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Åkerblom S, Perrin S, Rivano Fischer M, McCracken LM. The mediating role of acceptance in multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. J Pain. 2015;16(7):606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns JW. Mechanisms, mechanisms, mechanisms: it really does all boil down to mechanisms. Pain. 2016;157(11):2393–2394. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halmetoja CO, Malmquist A, Carlbring P, Andersson G. Experiences of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder four years later: a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2014;1(3):158–163. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donkin L, Glozier N. Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: a qualitative study of treatment completers. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e91. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heapy A, Otis J, Marcus KS, et al. Intersession coping skill practice mediates the relationship between readiness for self-management treatment and goal accomplishment. Pain. 2005;118(3):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller WR, Rollnick SP. Motivational Interviewing Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns JW, Nielson WR, Jensen MP, Heapy A, Czlapinski R, Kerns RD. Specific and general therapeutic mechanisms in cognitive behavioral treatment of chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):1–11. doi: 10.1037/a0037208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sokunbi O, Cross V, Watt P, Moore A. Experiences of individuals with chronic low back pain during and after their participation in a spinal stabilisation exercise programme – a pilot qualitative study. Man Ther. 2010;15(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahl JC, Wilson KG, Luciano C, Hayes SC. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain. Reno: Context Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCracken LM, Yang SY. The role of values in a contextual cognitive-behavioral approach to chronic pain. Pain. 2006;123(1–2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav Ther. 2004;35(4):639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundgren T, Luoma JB, Dahl J, Strosahl K, Melin L. The bull’s-eye values survey: a psychometric evaluation. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(4):518–526. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Farrer L. Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(2):e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin RK. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peräkylä A, Ruusuvuori J. Analyzing talk and text. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Open Code 3.1 [computer program] University of Umeå; Sweden: 2013. [Accessed June 1, 2018]. Available from: http://www.phmed.umu.se/english/units/epidemiology/research/open-code. [Google Scholar]