Abstract

Objectives

To explore young adult smokers’ perceptions of cigarette pack inserts promoting cessation and cigarettes designed to be dissuasive.

Design

Cross-sectional online survey.

Setting

UK.

Participants

The final sample was 1766 young adult smokers, with 50.3% male and 71.6% white British. To meet the inclusion criteria, participants had to be 16–34 years old and smoke factory-made cigarettes.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Salience of inserts, perceptions of inserts as information provision, perceptions of inserts on quitting, support for inserts and perceived appeal, harm and trial of three cigarettes (a standard cigarette, a standard cigarette displaying the warning ‘Smoking kills’ and a green cigarette).

Results

Half the sample indicated that they would read inserts with three-fifths indicating that they are a good way to provide information about quitting (61%). Just over half indicated that inserts would make them think more about quitting (53%), help if they decided to quit (52%), are an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit (53%) and supported having them in all packs (55%). Participants who smoked factory-made cigarettes and other tobacco products (compared with exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers), had made a quit attempt within the last 6 months (compared with those that had never made a quit attempt) or were likely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months (compared with those unlikely to make a quit attempt in the next 6 months) were more likely to indicate that inserts could assist with cessation. Multivariable logistic regression modelling suggested that compared with the standard cigarette, the cigarette with warning (adjusted OR=17.71; 95% CI 13.75 to 22.80) and green cigarette (adjusted OR=30.88; 95% CI 23.98 to 39.76) were much less desirable (less appealing, more harmful and less likely to be tried).

Conclusions

Inserts and dissuasive cigarettes offer policy makers additional ways of using the pack to reduce smoking.

Keywords: smoking, packaging, inserts, cigarettes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of this study is that it allows an insight into how young adult smokers perceive two innovative tobacco control measures (pack inserts promoting cessation and dissuasive cigarettes).

The main limitation of the study is that it does not provide any insight into actual smoking behaviour.

Additional limitations include the novelty of the stimuli and forced exposure to this and the use of self-selection.

Introduction

While packaging remains a key marketing driver for tobacco companies, more than 100 countries now require pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs,1 which can limit pack appeal.2 Some countries have gone even further by implementing plain (or standardised) packaging, which severely reduces the promotional power of the pack. The UK became the third country to fully implement standardised packaging in May 2017, following Australia in December 2012 and France in January 2017. In the UK, all cigarette packs must be drab brown with pictorial warnings on 65% of the front and back of packs and additional health messages on 50% of the sides of the pack. Although these changes have reduced the ability of tobacco companies to use the pack to create favourable perceptions of the brand and of smoking, there is clearly more scope for using the packaging to dissuade consumers. Regulators and academics have typically focused on the exterior of the cigarette pack, with little consideration of how the pack interior, for instance, pack inserts or cigarettes, which have long been used by tobacco companies to promote their brands, could potentially be used to encourage smokers to think about their smoking behaviour. This is the focus of our study.

Tobacco companies have used the inside of the cigarette pack to communicate with consumers since the late 19th century, via cigarette cards, coupons and promotional inserts. Only in Canada are they required, by law, to include pack inserts with health messaging. Sixteen text-only inserts were required in packs between 2000 and 2012, with nine encouraging cessation and seven providing health risk information.3 These were replaced with eight new inserts, with coloured graphics and positively framed messages about the benefits of quitting or tips on how to do so, in 2012. Few studies have explored perceptions of pack inserts,4–8 with only two assessing smokers’ perceptions of, and responses to, the inserts used in Canada.9–11 In focus group research in Scotland,9 with smokers aged 16 years and over who were shown seven of the inserts used in Canada, the general view was that they would capture attention and be read due to their novelty and visibility when opening the pack. Inserts were also thought to have a long-lasting impact as they would be removed from the pack and remain visible within the household or elsewhere or as litter.9 The positive messaging was liked and thought to increase message engagement. The inserts were often preferred to the on-pack warnings, although both were deemed necessary. Some participants suggested that inserts could encourage them to stop smoking, and they were generally considered to have the potential to alter the behaviour of younger people, would-be smokers and those wanting to quit.9 In Canada, a longitudinal online survey with smokers aged 18 years and over found that between 26% and 31% at each wave reported having read pack inserts at least once in the prior month; those intending to quit or having recently tried to do so were significantly more likely to have read them.10 In addition, while reading warnings on the pack exterior decreased over time, reading pack inserts increased over time, with more frequent reading independently associated with self-efficacy to quit, quit attempts and sustained quitting at follow-up.11

The cigarette itself is also an important communications tool,12 13 which has long been used by tobacco companies as a marketing device but has yet to be used by regulators to deter smoking. As cigarettes are primarily responsible for tobacco-related mortality and morbidity and predicted to continue to dominate the global market for some time yet,14 research exploring the potential impact of standardising the appearance of cigarettes to make them less desirable is long overdue. Some recent research has examined consumer perceptions of cigarettes that have been designed to be ‘dissuasive’, including unattractively coloured cigarettes,15 16 cigarettes with the warning ‘Smoking kills’ on the cigarette paper17 18 and cigarettes displaying the ‘minutes of life lost due to smoking’ on the cigarette paper.19 In each of these studies, the dissuasive cigarettes were generally viewed more negatively than regular cigarettes. For instance, a qualitative study with young women smokers in New Zealand found that unattractively coloured cigarettes, particularly green or brown coloured cigarettes, were perceived as more harmful than other cigarettes, with it less likely that they or others their age would want to use them.15 An in-home survey in the UK with individuals aged 11–16 years, who were shown an image of a cigarette stick displaying ‘Smoking kills’, found that 53% indicated that this would make people want to give up smoking, 71% indicated that it would put people off starting to smoke and 85% supported having a warning on all cigarettes.18

In this study, our objective was to explore, for the first time, young adult smokers’ perceptions of pack inserts and dissuasive cigarettes (a cigarette displaying the warning ‘Smoking kills’ and a green coloured cigarette).

Methods

Design and sample

An online survey was conducted in January–February 2016 with smokers aged 16–34 years in the UK; an online survey is a suitable approach given that 99% of this age group in the UK are recent internet users.20 The sample (n=1970) was recruited by online market research company ‘Research Now’ from their panel of over 400 000 people (www.researchnow.com). After Research Now excluded those who had completed the survey in less than the minimum completion time (n=193), which they had set prior to data collection commencing, and those providing responses to open-ended questions that indicated that they had not taken the survey seriously (n=11), the final sample was 1766 (89.6% of completed surveys). The final sample was 50.3% male, with 53.9% aged 25–34 years and 71.6% white British. Most participants smoked 10 or less cigarettes per day, with 46.0% exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers (see table 1 for sample and smoking-related characteristics).

Table 1.

Sample and smoking-related characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % |

| Total | 1766 | 100.0 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 16–19 | 413 | 23.4 |

| 20–24 | 401 | 22.7 |

| 25–34 | 952 | 53.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 888 | 50.3 |

| Female | 878 | 49.7 |

| Educational qualifications | ||

| Other qualifications | 1357 | 76.8 |

| None or GCSE | 409 | 23.2 |

| Economic status | ||

| Other status | 1350 | 76.4 |

| Routine or manual occupation, unemployed or long-term sick | 416 | 23.6 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||

| No indicators of low SES | 1114 | 63.1 |

| Low education and/or low SES | 652 | 36.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 1264 | 71.6 |

| White non-British | 162 | 9.2 |

| Black (including mixed black and white) | 79 | 4.5 |

| Asian (including mixed Asian and white) | 196 | 11.1 |

| Other or not declared | 65 | 3.7 |

| Location | ||

| England | 1550 | 87.8 |

| Scotland | 109 | 6.2 |

| Wales | 73 | 4.1 |

| Northern Ireland | 34 | 1.9 |

| Tobacco products used | ||

| Only factory-made (packet) cigarettes | 813 | 46.0 |

| Factory-made and roll-your-own cigarettes | 681 | 38.6 |

| Factory-made cigarettes and other products (eg, cigars and shisha) | 272 | 15.4 |

| Cigarettes per day | ||

| 10 or less | 1272 | 72.0 |

| 11–20 | 433 | 24.5 |

| 21–30 | 46 | 2.6 |

| 31 or more | 15 | 0.8 |

| Time to first cigarette | ||

| Within 5 min | 263 | 14.9 |

| 6–30 min | 570 | 32.3 |

| 31–60 min | 315 | 17.8 |

| After 60 min | 618 | 35.0 |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) | ||

| 0 little dependence | 601 | 34.0 |

| 1 | 257 | 14.6 |

| 2 | 418 | 23.7 |

| 3 | 293 | 16.6 |

| 4 | 156 | 8.8 |

| 5 | 28 | 1.6 |

| 6 high dependence | 13 | 0.7 |

| Dependence (tertiles of HSI) | ||

| Low dependence | 601 | 34.0 |

| Mid-dependence | 675 | 38.2 |

| High dependence | 490 | 27.7 |

| Made an attempt to quit smoking that lasted at least 24 hours? | ||

| Yes, within the last 6 months | 788 | 44.6 |

| Yes, more than 6 months ago | 552 | 31.3 |

| No, I have never tried to quit smoking for more than 24 hours | 426 | 24.1 |

| How likely are you to try to quit smoking within the next 6 months? | ||

| Not at all | 198 | 11.2 |

| A little | 382 | 21.6 |

| Moderately | 508 | 28.8 |

| Very | 308 | 17.4 |

| Extremely | 272 | 15.4 |

| Don’t know | 98 | 5.5 |

| If you decided to quit smoking in the next 6 months, how sure are you that you would succeed? | ||

| Not at all | 147 | 8.3 |

| A little | 346 | 19.6 |

| Moderately | 612 | 34.7 |

| Very | 297 | 16.8 |

| Extremely | 241 | 13.6 |

| Don’t know | 123 | 7.0 |

| Quit approach | ||

| Moderately or less likely to make quit attempt in next 6 months (unlikely to make a quit attempt in the next 6 months). |

1186 | 67.2 |

| Very or extremely likely to attempt but moderately or less likely to succeed (unlikely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months). |

304 | 17.2 |

| Very or extremely likely to attempt and very or extremely likely to succeed (likely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months). |

276 | 15.6 |

GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education.

Procedure

An email invite was sent by Research Now to their online panel in the UK. Research Now is an established online market research company in the UK and elsewhere,21 with their panels recruited from a wide range of sources, such as internet sites, advertising and partnerships with other websites. Research Now, like other online panels, has details of their members’ demographics and other characteristics that are used to profile target samples. Response rate details are not available when using this sampling methodology, however, as recording contact, participation and refusal rates are not practical.22 For those who responded to the email invite, they answered screening questions about their age, smoking status and types of tobacco products used, while those who did not meet the inclusion criteria (factory-made cigarette smokers aged 16–34 years) were excluded.

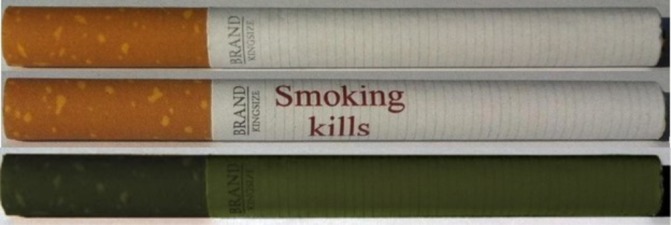

Those eligible for inclusion were presented with an information page explaining the study aim (to explore what young adult smokers thought about cigarettes and pack inserts) and relevant ethical information (their right to withdraw at any time, assurances of confidentiality and anonymity and contact details if they had any concerns or would like to request a copy of the published findings). They were then presented with a consent page, with consent required for participation. Survey questions were presented in the same order for all participants, except the questions exploring perceptions of the three cigarette types (standard cigarette (SC), warning cigarette (WC) and green cigarette (GC)), where the ordering was randomised; the ordering of the presentation of the three cigarettes (shown in figure 1) was also randomised. There was no missing data as participants could only proceed to the next question if they had provided an answer to the previous question.

Figure 1.

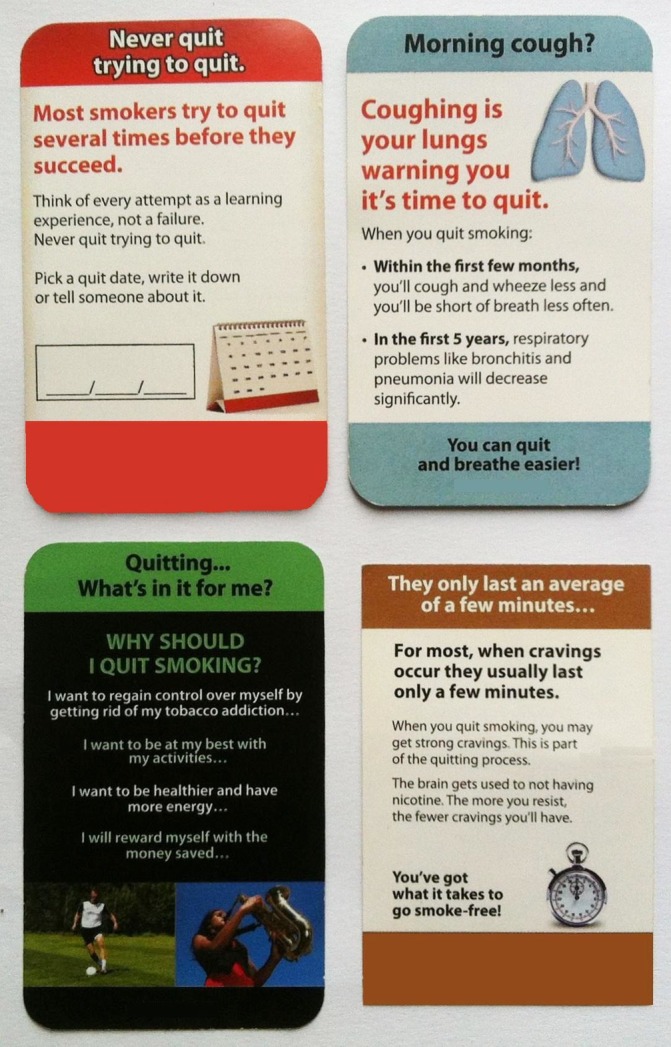

Standard cigarette, warning cigarette and green cigarette.

Prior to the questions on inserts, participants were shown an image of a cigarette pack with an insert shown in the front of the pack—as they typically appear in packs—alongside the text ‘We have some questions on pack inserts, which can sometimes be found inside packs (see image for example)’. For each question about inserts, participants were shown the question and an image of one insert. Four different inserts were used in total, as shown in figure 2, with these chosen from the eight used in Canada as they were considered most relevant to our sample. The words ‘Health Canada’ were removed from the bottom of each insert to make them more relevant for participants in the UK. The median time for survey completion was 9 min 28 s. Participants received a nominal incentive (50 pence) for participation, as is common for online panels.

Figure 2.

Pack inserts highlighting the benefits of quitting or providing tips on how to do so.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the development, design or conduct of this study.

Measures

Inserts: salience and information provision

Participants were asked ‘If this type of insert was in your cigarette pack, do you think that you would read it?’ and ‘If this type of insert was in your cigarette pack, do you think that you would read it if you were interested in quitting?’ They were also asked ‘Do you think that inserts would be a good way to provide information to smokers about quitting?’5 Response options for each were ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Not sure’.

Inserts: cessation

Three questions assessed to what extent participants agreed or disagreed that inserts would make them think about quitting and help them quit: ‘Do you agree or disagree that having these types of inserts in every cigarette pack would make you think more about quitting?’, ‘Do you agree or disagree that having these types of inserts in every cigarette pack might help you if you decided to quit?’ and ‘Do you agree or disagree that having these types of inserts inside every cigarette pack would be an effective way of helping smokers who want to quit?’6 Response options for each were ‘Strongly disagree’, ‘Disagree’, ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Don’t know’.

Inserts: support

A five-point semantic scale assessed support, with anchors ‘All cigarette packs should have inserts like this in them-No cigarette packs should have inserts like this in them’.

Cigarette design: appeal, harm and trial

Seven-point semantic scales assessed appeal, harm and likely trial. Appeal was assessed via four scales, with anchors ‘Attractive-Unattractive’, ‘Stylish-Not stylish’, ‘Not nice to be seen with-Nice to be seen with’ and ‘Not appealing to people my age-Appealing to people my age’. Harm was assessed via two scales, with anchors ‘Looks harmful to health-Does not look harmful to health’ and ‘Makes me think about the dangers of smoking-Does not make me think about the dangers of smoking’. Likely trial was assessed via two scales: ‘If a friend offered you each of these cigarettes, how likely would you be to try them?’ and ‘If someone your age who had never smoked before was going to try a cigarette, how likely do you think they would be to try each of these cigarettes?’. Both scales assessing trial ranged from ‘Not at all likely’ to ‘Very likely’.

A factor analysis of the eight variables on appeal, harm and trial, collated for the three cigarette types (SC, WC and GC), was undertaken. Checks indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin=0.845, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (approx. χ2 18 062.842, df=276, p<0.001), with no correlations between the variables >0.9). The extraction method used was principal axis factoring, and the criteria for extraction was eigenvalues >1. All eight variables loaded on a single factor with factor loadings that were >0.5. High factor scores indicated that a cigarette was desirable, and low scores indicated that it was undesirable. The factor was used as the outcome measure of cigarette desirability in the regression analysis. Visual inspection and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the factor was non-normal (because responses for the dissuasive cigarettes indicated they were undesirable generally), and attempts to normalise it using normit rankit methods failed. Therefore, the factor was divided into tertiles, with the tertile indicating undesirable factor scores compared with the other two tertiles. This was the outcome variable in logistic regression analysis.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment and economic status (based on chief income earner) were obtained. Preliminary analysis showed that education was associated with how pack inserts were perceived, whereas both education and economic status were associated with how cigarettes were perceived. As such, for the analysis of the cigarettes, a count procedure was used to create a variable for low socioeconomic status (SES): low education (General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) or below) and/or low economic status (routine or manual occupation, long-term unemployed or long-term sick or disabled).

Smoking behaviour

Smoking status was assessed with ‘Which of these best describes you?’ with response options: ‘I have never smoked’, ‘I used to smoke, but don’t now’, ‘I smoke, but not every day’ and ‘I smoke every day’. Type of products used was assessed with ‘What type(s) of tobacco products do you smoke?’ with response options: ‘Only factory-made (packet) cigarettes’, ‘Factory-made and roll-your-own cigarettes’, ‘Factory-made cigarettes and other tobacco products (eg, cigars, shisha, etc)’, ‘Only roll-your-own cigarettes’ and ‘Only other tobacco products (eg, cigars, shisha, etc)’. The Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI)23 was used as a measure of dependence, based on daily consumption and time to first cigarette.

Quitting and self-efficacy

Participants were asked ‘Have you ever made an attempt to quit smoking that lasted at least 24 hours?’24 (yes within the last 6 months, yes more than 6 months ago and I have never tried to quit for more than 24 hours). They were also asked ‘How likely are you to try to quit smoking within the next six months?’25 (not at all, a little, moderately, very, extremely and don’t know), with those responding ‘Not at all’, ‘A little’, ‘Moderately’ or ‘Don’t know’ classified as ‘Unlikely to make a quit attempt in the next six months’. To measure quitting self-efficacy, participants were asked ‘If you decided to quit smoking in the next six months, how sure are you that you would succeed?’26 (not at all, a little, moderately, very, extremely and don’t know). Those who responded to the likelihood of quitting question with ‘Very or ‘Extremely’ and to the quitting efficacy question with ‘Not at all’, ‘A little’, ‘Moderately’ or ‘Don’t know’ were classified as ‘unlikely to make a successful quit attempt in the next six months’. Those who responded ‘Very’ or ‘Extremely’ to both questions were classified as ‘likely to make a successful quit attempt in the next six months’.

Analysis

Data were analysed using Microsoft Office Excel 2013, SPSS V.22 and V.23 and MLWin V.2.33.27 The insert variables were dichotomised into yes/agreement and no/disagreement/neutral/not sure/don’t know. The dichotomised insert variables were the outcomes of the logistic regression models. The independent variables were gender, age, education, ethnicity, dependence (tertiles of HSI), tobacco product(s) smoked, previous quit attempt lasting at least 24 hours and likely efficacy of a quit attempt in the next 6 months. Percentages in agreement were calculated. Age, gender and education (as a measure of SES) were entered into all models to account for any sampling inadequacies. Other variables were entered where p<0.10 in χ2 tests. The models were assessed for multicollinearity via comparison of SEs,28 and none was found.

For each of the eight seven-point semantic scales, the percentage of participants choosing one of the three points nearest the undesirable anchor (eg, unattractive, not nice to be seen with and looks harmful to health) was calculated for each of the three cigarette types (SC, WC and GC). Thus, 24 percentages were calculated. Differences between the three cigarettes were tested using Cochran’s Q and pairwise comparisons.

Multilevel logistic regression modelling of cigarette desirability, with second order PQL estimation,29 was undertaken with cigarette evaluations (participants’ response to each of the three cigarettes) clustered within individual participants. Therefore, cigarette evaluations were level one cases, and participants were entered at level two as a random effect. All models included cigarette type as a fixed effect, where the SC was compared with the WC and GC. Other fixed effects at the individual (participant) level were sociodemographic and smoking-related characteristics, which were significantly associated with the outcome in multivariable models. This main effects model tested which characteristics were associated with perceiving cigarettes as desirable. In order to understand which characteristics differentiated the desirability of the three types of cigarettes, interactions between cigarette type and each significant characteristic were tested. Only one interaction was found, between cigarette type and SES. The interacting variables (cigarette type and SES) were substituted by a cross-classified variable, which merged cigarette type and SES. This cross-classified variable was split into six categories: low SES SC, low SES WC, low SES GC, not low SES SC, not low SES WC and not low SES GC. To understand, the interaction five models were run with the reference category of the cross-classified variable different each time.30 31

Results

Perceptions of inserts

Half the sample indicated that they would read inserts, with approximately three-fifths indicating that they would read them if interested in quitting (60%) and that they would be a good way to provide information about quitting (61%). Just over half strongly agreed/agreed that inserts may make them think more about quitting (53%), help them if they decided to quit (52%), that they are an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit (53%) and that all cigarette packs should have inserts (55%) (see table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of whether inserts would be read, are a good way to provide information, whether they would help smokers to think about quitting or quit, and support for them

| Yes % | No % | Not sure % | |

| Would they be read | 50 | 37 | 13 |

| Would they be read if interested in quitting | 60 | 25 | 15 |

| Good way to provide information about quitting | 61 | 25 | 14 |

| Agree % | Disagree % | Neither/don’t know % | |

| Make you think more about quitting | 53 | 18 | 29 |

| Might help you if you decided to quit | 52 | 19 | 29 |

| Effective way of encouraging smokers to quit | 53 | 17 | 30 |

| All packs should have inserts | 55 | 20 | 25 |

Sociodemographic differences in perceptions of inserts

Women were more likely than men to indicate that they would read inserts (adjusted OR (aOR)=1.24; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.50), and individuals aged 25–34 years were less likely than individuals aged 16–19 years to think that they were a good way of providing information about quitting (aOR=0.76; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.98). Compared with white British participants, white non-British (aOR=0.70; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.98) and Asian (aOR=0.67; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.92) participants were less likely to suggest that they would read inserts if trying to quit, white non-British (aOR=0.58; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.81) and black (aOR=0.61; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.98) participants were less likely to indicate that inserts would make them think about quitting, and white non-British (aOR=0.62; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.87) and Asian (aOR=0.70; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.96) participants were less likely to support having inserts in all packs (see table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models exploring perceptions of inserts by sociodemographic and smoking related characteristics*

| (n=1766) | Would read insert | Would read insert if trying to quit | Inserts make you think about quitting | Inserts might help you quit | Inserts a good way of providing information about quitting | Inserts are an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit | All packs should have inserts |

| Gender (ref†=male) | |||||||

| Female | 1.24 (1.02 to 1.50) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.35) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.19) | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.15) | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.37) | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.07) | 1.20 (0.99 to 1.46) |

| Age (years) (ref=16–19 years) | |||||||

| 20–24 | 1.16 (0.87 to 1.54) | 0.88 (0.66 to 1.18) | 1.18 (0.89 to 1.56) | 1.19 (0.89 to 1.58) | 0.87 (0.65 to 1.16) | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.28) | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.29) |

| 25–34 | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.60) | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.07) | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.26) | 1.18 (0.92 to 1.50) | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.98) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.12) | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.07) |

| Education (ref=GCSEs (or equivalent) or none) | |||||||

| More than GCSEs (or equivalent) | 1.25 (0.99 to 1.58) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.42) | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) | 1.21 (0.97 to 1.52) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.40) | 1.19 (0.95 to 1.50) | 1.10 (0.87 to 1.40) |

| Ethnicity (ref=white British) | |||||||

| White but not British | 0.70 (0.50 to 0.98) | 0.58 (0.41 to 0.81) | 0.62 (0.44 to 0.87) | ||||

| Black (inc mixed black and white) | 0.92 (0.57 to 1.49) | 0.61 (0.38 to 0.98) | 0.99 (0.62 to 1.59) | ||||

| Asian (inc mixed Asian and white) | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.92) | 1.19 (0.87 to 1.63) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.96) | ||||

| Other or not declared | 0.84 (0.50 to 1.42) | 1.06 (0.64 to 1.78) | 1.08 (0.64 to 1.81) | ||||

| Dependence (tertiles of HSI) (ref=lower dependence) | |||||||

| Mid dependence | 1.39 (1.11 to 1.76) | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.29) | |||||

| Higher dependence | 1.22 (0.94 to 1.59) | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.12) | |||||

| Tobacco products smoked (ref=only factory-made cigarettes) | |||||||

| Factory made and roll your own | 1.35 (1.09 to 1.66) | 1.61 (1.30 to 2.00) | 1.31 (1.06 to 1.62) | 1.31 (1.06 to 1.61) | 1.27 (1.03 to 1.56) | ||

| Factory-made and other | 1.20 (0.90 to 1.59) | 1.39 (1.04 to 1.86) | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.63) | 1.34 (1.01 to 1.78) | 1.20 (0.91 to 1.60) | ||

| Quit attempt lasting at least 24 hours (ref=no) | |||||||

| Yes, more than 6 months ago | 1.30 (1.00 to 1.69) | 1.12 (0.86 to 1.45) | 1.20 (0.93 to 1.56) | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.36) | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.50) | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.38) | 0.78 (0.60 to 1.01) |

| Yes, within the last 6 months | 1.67 (1.29 to 2.15) | 1.51 (1.17 to 1.94) | 1.46 (1.14 to 1.88) | 1.35 (1.05 to 1.73) | 1.54 (1.20 to 1.98) | 1.33 (1.04 to 1.71) | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.37) |

| Efficacy of quit attempt in next 6 months (ref=likely to quit) | |||||||

| Likely to make unsuccessful attempt | 1.01 (0.72 to 1.40) | 1.43 (1.00 to 2.06) | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.37) | 0.92 (0.65 to 1.29) | 1.46 (1.02 to 2.08) | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.55) | 1.43 (1.00 to 2.04) |

| Unlikely to make attempt | 0.58 (0.44 to 0.75) | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.99) | 0.59 (0.45 to 0.78) | 0.51 (0.38 to 0.67) | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.01) | 0.55 (0.41 to 0.73) | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.74) |

*Blank cells indicate no significant relationship in bivariate analysis.

†ORs for reference categories are always 1.

GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; HSI, Heaviness of Smoking Index.

Smoking-related differences

Compared with exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers, those who also smoked roll-your-own cigarettes were more likely to indicate they would read inserts (aOR=1.35; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.66), read them if trying to quit (aOR=1.61; 95% CI 1.30 to 2.00), that they would make them think about quitting (aOR=1.31; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.62), help them if they decided to quit (aOR=1.31; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.61) and that they would be an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit (aOR=1.27; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.56) (see table 3). Compared with exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers, those who also smoked other tobacco products (eg, cigars, shisha) were more likely to indicate they would read inserts if trying to quit (aOR=1.39; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.86) and that inserts might help them if they decided to quit (aOR=1.34; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.78).

Participants who had made a quit attempt more than 6 months ago (aOR=1.30; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.69), or within the last 6 months (aOR=1.67; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.15), were more likely to indicate that they would read inserts than those who had never made a quit attempt. Those who had made a quit attempt in the last 6 months were also more likely than those who had never made a quit attempt to indicate that inserts were a good way to provide information about quitting (aOR=1.54; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.98), that they would read them if trying to quit (aOR=1.51; 95% CI 1.17 to 1.94), make them think about quitting (aOR=1.46; 95% CI 1.14 to 1.88), help them if they decided to quit (aOR=1.35; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.73) and that they would be an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit (aOR=1.33; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.71).

Compared with those likely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months, those unlikely to make a quit attempt in the next 6 months were less likely to indicate that they would read inserts (aOR=0.58; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.75), read them if trying to quit (aOR=0.74; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.99), that they would make them think about quitting (aOR 0.59; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.78), help them if they decided to quit (aOR=0.51; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.67), that they would be effective for smokers if they decided to quit (aOR=0.55; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.73) or support them (aOR=0.56; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.74). Compared with those likely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months, those unlikely to make a successful quit attempt in the next 6 months were more likely to read inserts if trying to quit (aOR=1.43; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.06), thought that they were a good way to provide information to smokers about quitting (aOR=1.46; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.08) and support them (aOR=1.43; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.04).

Perceptions of cigarette design

With respect to harm, participants were less likely to think that the SC looked harmful than the WC or GC (p<0.001) and less likely to think that the SC made them think more about the dangers of smoking than the WC or GC (p<0.001) (see table 4) Participants were also less likely to indicate that the GC would make them think of the dangers of smoking than the WC (p=0.01). In terms of appeal, participants were more likely to consider the SC attractive, and stylish, than the WC or GC (both p<0.001). The SC was also considered to be nicer to be seen with, and more appealing to people their age, than the WC or GC (both p<0.001). In terms of trial, whereas only 8.9% indicated that they would be unlikely to try a SC if offered by a friend, this was 45.4% for the WC and 66.5% for the GC (both p<0.001). Similarly, while only 14.8% indicated that a never smoker their age would be unlikely to try a SC, this was 63.3% for the WC and 71.6% for the GC (both p<0.001) (see table 4).

Table 4.

Perceptions of cigarette design (harm, appeal and trial)

| Standard cigarette (SC) %* |

Cigarette with warning (WC) %* |

Green Cigarette (GC) %* |

|

| Harmful to health | 38.8 | 69.1† | 70.2† |

| Think of dangers | 20.9 | 58.1†‡ | 53.5† |

| Unattractive | 25.2 | 61.7† | 68.7† |

| Unstylish | 37.4 | 66.0† | 69.4† |

| Not nice to be seen with | 19.8 | 55.2† | 60.2† |

| Not appealing to people my age | 17.8 | 51.5† | 57.4† |

| Unlikely to try (personally) | 8.9 | 45.4† | 66.5† |

| Unlikely to try (for never smokers) | 14.8 | 63.3† | 71.6† |

*Percentages shown indicate participants choosing one of the three points nearest the undesirable anchor on a seven-point semantic scale.

†Significant difference in comparison with the standard cigarette (p<0.001).

‡Significant difference in comparison with the green cigarette (p<0.05).

Perceptions of cigarette desirability

Main effects multivariable logistic regression modelling suggested that in comparison with the SC, the WC (aOR=17.71; 95% CI 13.75 to 22.80) and GC (aOR=30.88; 95% CI 23.98 to 39.76) were much more likely to be perceived as undesirable (ie, less appealing, more harmful and less likely to be tried). The model also indicated which smokers were more likely to rate the cigarettes as undesirable: women were more likely than men (aOR=1.30; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.54), and low SES more likely than those not low SES (aOR=1.26; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.50), to consider all three cigarettes undesirable. Compared with exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers, those who also smoked roll-your-own cigarettes (aOR=0.78; 95% CI 0.65 to 0.93) or other tobacco products (aOR=0.73; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.93) were less likely to consider all three cigarettes undesirable. Those not likely to make a quit attempt in the next 6 months were less likely than those likely to make a quit attempt in the next 6 months (aOR=0.62; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.78) to consider all three cigarettes undesirable.

Only one significant interaction, between cigarette type and SES, was found (p<0.05). Both SES groups perceived the WC significantly more undesirable than the SC and the GC significantly more undesirable than the WC (see table 5). Low SES participants were significantly more likely than those not low SES to perceive the SC (aOR=1.89; 95% CI 1.18 to 3.03) and GC (aOR=1.43; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.80) as undesirable; there was no difference for the WC (aOR=0.99; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.25).

Table 5.

Multilevel and multivariable modelling of perceiving cigarettes as undesirable (n=5298 cigarette evaluations, u=1766 participants)

| Multivariable model | Multivariable model+cigarette*SES interaction | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Cons | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.07) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) |

| Cigarette type | ||

| Warning on cigarette | 17.71 (13.75 to 22.80) | 23.29 (16.40 to 33.08) |

| (ref=standard cigarette†) | ||

| Green cigarette | 30.88 (23.98 to 39.76) | 35.41 (24.93 to 50.29) |

| Gender (ref=male) | ||

| Female | 1.30 (1.10 to 1.54) | 1.30 (1.10 to 1.55) |

| SES (ref=higher SES) | ||

| Low education and/or low economic status | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.50) | 1.89 (1.18 to 3.04) |

| Ethnicity (ref=white British) | ||

| White but not British | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.30) | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.30) |

| Black (including mixed black and white) | 0.94 (0.62 to 1.42) | 0.94 (0.62 to 1.42) |

| Asian (including mixed Asian and white) | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.05) | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.05) |

| Other or not declared | 0.90 (0.58 to 1.42) | 0.90 (0.57 to 1.42) |

| Product category | ||

| Factory-made and roll-your-own cigarettes | 0.78 (0.65 to 0.90) | 0.77 (0.64 to 0.93) |

| (ref=factory–made only) | ||

| Factory-made cigarettes and other tobacco products (eg, cigars and shisha) | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.93) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.93) |

| Efficacy (ref=likely to quit) | ||

| Not likely to make a quit attempt in next 6 months | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.78) | 0.61 (0.49 to 0.78) |

| Likely to make unsuccessful attempt | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.41) | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.41) |

| Interaction cigarette type*SES | ||

| WC*low SES | 0.52 (0.31 to 0.87) | |

| (ref=SC*higher SES) | ||

| GC*low SES | 0.76 (0.46 to 1.26) | |

| Variation between participants (U(SE)) | 1.14 (0.11) | 1.14 (0.11) |

| Models varying reference category of cross-classified variable* | |||||

| Reference category: | SC not low SES, OR (95% CI) | SC low SES, OR (95% CI) | WC not low SES, OR (95% CI) | WC low SES, OR (95% CI) | GC not low SES, OR (95% CI) |

| Cigarette type and SES | |||||

| SC: not low SES | 1 | 0.53 (0.33 to 0.85) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) |

| SC: low SES | 1.89 (1.18 to 3.03) | 1 | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.12) | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.12) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.08) |

| WC: not low SES | 23.13 (16.28 to 32.85) | 12.21 (8.48 to 17.58) | 1 | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.79) |

| WC: low SES | 22.83 (15.58 to 33.46) | 12.05 (8.37 to 17.35) | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.25) | 1 | 0.65 (0.52 to 0.82) |

| GC: not low SES | 35.09 (24.71 to 49.84) | 18.52 (12.86 to 26.67) | 1.52 (1.27 to 1.81) | 1.54 (1.22 to 1.94) | 1 |

| GC: low SES | 50.15 (34.29 to 73.35) | 26.47 (18.35 to 38.19) | 2.17 (1.72 to 2.74) | 2.20 (1.74 to 2.77) | 1.43 (1.13 to 1.80) |

*Variables included are those in the above models with the exception that cigarette type and SES are replaced with the cross classified variable.

GC, green cigarette; SC, standard cigarette; SES, socioeconomic status; WC, warning cigarette.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that inserts highlighting the benefits of quitting or providing tips on how to do so may have the potential to encourage cessation, and dissuasive cigarettes may help to reduce the desirability of smoking. Just as tobacco companies have used inserts and cigarette design to create interest in their products, our study suggests that greater attention to how these could be used to promote cessation appears warranted.

Health messages need to capture attention to be effective.32 In this regard, at least half our sample indicated that they would read inserts (50%) and read them if interested in quitting (60%). In Canada, an observational study found that approximately a quarter of smokers reported reading them at least once within the last month,10 increasing to about one-third of smokers over 2 years of follow-up.11 Like the smokers in our study who indicated that they would read the inserts, smokers in Canada who had read the inserts were more likely to be female, intend to quit or had recently tried to quit; in our study, they were also more likely to be white British, have moderate dependence and use factory-made cigarettes and other tobacco products. Future research could explore why dual users (smokers of factory-made cigarettes and other tobacco products) were more likely to indicate that they would read inserts, but as inserts are typically only found in cigarette packs, then for those who use other tobacco products, they may be seen as more of a novelty and therefore more likely to capture attention.

Approximately three-fifths (61%) of smokers in our study thought that inserts were a good way to provide information about quitting to smokers, with only 25% disagreeing. In comparison, an earlier study in Canada, commissioned by Health Canada, found that 48% of smokers indicated that messaging on inserts was a good way to provide information to smokers, with 47% disagreeing.5 Just over half our sample agreed/strongly agreed that inserts may make them think more about quitting, help them if they decided to quit and that they are an effective way of encouraging smokers to quit, whereas in New Zealand, only 34% of smokers and recent quitters agreed/strongly agreed that inserts would be an effective way of encouraging reduced consumption or quitting.6 There may be various reasons for the differences between our findings and earlier research. For instance, when this earlier research was conducted, cigarette packs displayed text-only health warnings, and it may be that having pictorial warnings on packs, as is required in Scotland, may prompt smokers to look for information on how to quit and the benefits of doing so. Insert design is also likely to be relevant. Whereas the inserts used in earlier research were limited to text, the inserts used in this study (which have been used in Canada since 2012) included coloured graphics, which is typical of promotional inserts used by tobacco companies and likely enhanced their impact. This would be consistent with the health communications and warnings literature, which demonstrates the importance of supporting text with pictorials.32 33 Future research exploring insert design (eg, use of imagery, inclusion of cessation resource information and length and framing of messages) would be of value.

More than half our sample supported the inclusion of inserts promoting cessation inside every cigarette pack, with only a fifth opposing this. Within the European Union, the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD)34 does not require tobacco companies to include health communication inserts in packs but allows member states to introduce measures beyond those specified. Among governmental representatives that responded to the consultation on the revision of the TPD, there was strong support for improving consumer information via mandatory pictorial warnings, with those supportive arguing that additional information, such as pack inserts, would help to deliver more accurate health information.35 If there is support for inserts among governmental representatives, and little opposition among smokers (the group most likely to be resistant), they are clearly a viable option for regulators.

Tobacco industry journals describe the cigarette as an increasingly important advertising medium for tobacco companies.12 However, until recently, the public health focus has been on the potential of regulating the contents of cigarettes to reduce palatability or addictiveness,36 with little consideration of the possibility of regulating the appearance of cigarettes to reduce its importance as a promotional tool. We found that the two dissuasive cigarettes were perceived as significantly more harmful and less appealing than the SC and less likely to encourage trial. The harm, appeal and trial items loaded onto a single ‘desirability’ factor, with the dissuasive cigarettes considered much more undesirable than the SC. The findings are consistent with earlier research, where cigarettes with the warning ‘Smoking kills’ were considered a constant reminder of the associated harms and, partly due to the perceived discomfort of being observed by others smoking a cigarette displaying this message, unappealing for smokers.8 16–18 Previous studies have also found unattractively coloured cigarettes to be perceived as more harmful than other cigarettes and also repellent, being a cigarette that young people did not think that others their age would use.15 16 37 38 As with the inserts, the dissuasive cigarettes (and also the SC) were considered more desirable among dual users than exclusive factory-made cigarette smokers; again, it is not clear why this was the case, but further research with dual users, or indeed those also using vaping devices (not assessed in this study), would be fruitful.

In terms of limitations, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to assess causality; that inserts and dissuasive cigarettes are not available on the UK market prevents more robust study designs such as longitudinal studies. Another potential limitation concerns the novelty of the stimuli, which may have influenced responses, and forced exposure to the stimuli. In addition, we only used four inserts, rather than the full set of eight used in Canada, which includes inserts less relevant to our sample. While online surveys have been used for previous research exploring cigarette packaging, inserts and dissuasive cigarettes39–42 and are a suitable survey mode for young adults, the use of an online panel and self-selection limits the representativeness of our sample. In addition, the use of semantic differential scales can be criticised because answers can be subject to various response biases, although we attempted to diminish these through varying scale item direction and through our multivariate modelling methodology.

It was argued, over two decades ago, that to offer greater protection to consumers cigarettes should come in plain packs with health messaging on both the pack exterior and interior.43 This idea is a step closer in the UK, although there will still be no messaging on the pack interior. That more than half of the participants in this study suggested that inserts may help to promote cessation suggests that their inclusion in packs may be a meaningful supplement to the on-pack warnings. Our findings suggest however that to offer the greatest protection to consumers, it may be beneficial to supplement plain packaging and inserts with cigarettes designed to be dissuasive. Unattractively coloured cigarettes would complement the unattractively coloured packs, just as warnings on the cigarette would extend the warnings on the cigarette pack. Both options are clearly viable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Kelvyn Jones for his help on this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: CSM designed the data collection tool and drafted and revised the paper. RH analysed the data and drafted the analysis and results. JT and GR helped design the data collection tool and commented on the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Health Scotland. GR, who works for Health Scotland, provided feedback on the survey and paper, but was not involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: GR works for Health Scotland, which funded this study.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study obtained ethics approval from the School of Health Sciences Ethics Committee at the University of Stirling. Participants provided informed consent before participating.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette package health warnings: In International status report. 5th edn, 2016. www.tobaccolabels.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Cigarette-Package-Health-Warnings-International-Status-Report-English-CCS-Oct-2016.pdf (accessed 10 Sep 2017).

- 2. Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control 2011;20:327–37. 10.1136/tc.2010.037630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahood G. Canada’s tobacco package label or warning system: “telling the truth” about tobacco product risks. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tandemar Research Inc. Tobacco health warning messages, inserts and toxic constituents information study - Final Report. Toronto: Tandemar Research Inc, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Environics. Health warning messages on the flip/side and inserts of cigarette packaging. A survey of smokers. 2000. A report prepared for Health Canada.

- 6. BRC Marketing and Social Research. Smoking health warnings study. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2004. www.tobaccolabels.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/NZ-2004-Effectiveness-of-Different-Health-Warnings-in-Helping-People-Consider-Their-Smoking-Related-Behaviour-Government-Report.pdf (accessed 12 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallopel-Morvan K, Moodie C, Hammond D, et al. Consumer understanding of cigarette emission labelling. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:373–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moodie C. Novel ways of using tobacco packaging to communicate health messages: Interviews with packaging and marketing experts. Addict Res Theory 2016;24:54–61. 10.3109/16066359.2015.1064905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moodie C. Adult smokers’ perceptions of cigarette pack inserts promoting cessation: a focus group study. Tob Control 2018;27:72–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thrasher JF, Osman A, Abad-Vivero EN, et al. The use of cigarette package inserts to supplement pictorial health warnings: An evaluation of the canadian policy. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:870–5. 10.1093/ntr/ntu246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thrasher JF, Swayampakala K, Cummings KM, et al. Cigarette package inserts can promote efficacy beliefs and sustained smoking cessation attempts: A longitudinal assessment of an innovative policy in Canada. Prev Med 2016;88:59–65. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rossell S. Ready to roll. Tob Report 2017;2:44–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13. C Smith K, Washington C, Welding K, et al. Cigarette stick as valuable communicative real estate: a content analysis of cigarettes from 14 low-income and middle-income countries. Tob Control 2016;26:604–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hedley D. Tobacco wars: A new hope - the changing future. Tob J Int 2015;3:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoek J, Robertson C. How do young adult female smokers interpret dissuasive cigarette sticks? J Soc Mark 2015;5:21–39. 10.1108/JSOCM-01-2014-0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoek J, Gendall P, Eckert C, et al. Dissuasive cigarette sticks: the next step in standardised (‘plain’) packaging? Tob Control 2016;25:699–705. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moodie C, Purves R, McKell J, et al. Novel means of using cigarette packaging and cigarettes to communicate health risk and cessation messages: A qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Addict 2015;13:333–44. 10.1007/s11469-014-9530-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moodie C, Mackintosh AM, Gallopel-Morvan K, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of health warnings on cigarettes. Nicot Tob Res 2017;29:1232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hassan LM, Shiu E. No place to hide: two pilot studies assessing the effectiveness of adding a health warning to the cigarette stick. Tob Control 2015;24:e3–e5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. ONS, 2017. Internet users in the UK www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2017 (accessed 15 Sep 2017).

- 21. Hoek J, Gendall P, Eckert C, et al. Effects of brand variants on smokers' choice behaviours and risk perceptions. Tob Control 2016;25:160–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moodie C, Sinclair L, Mackintosh AM, et al. How tobacco companies are perceived within the united kingdom: An online panel. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1766–72. 10.1093/ntr/ntw024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, et al. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend 1994;34:211–6. 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Etter JF, Sutton S. Assessing ‘stage of change’ in current and former smokers Trying to stop smoking: effects of perceived addiction, attributions for failure, and expectancy of success. Addiction 2002;97:1171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, et al. Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control 2003;12:391–5. 10.1136/tc.12.4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. IARC. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol. 12: Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rasbash J, Browne W, Healy M, et al. A user’s guide to MLwiN, version 2.3. Bristol: Centre for multilevel modelling, University of Bristol, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salmond C, 2006. Fitting complex models using health survey data www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/otago020178.pdf (accessed 15 Sep 2017).

- 29. Goldstein H, Rasbash J. Improved approximations for multilevel models with binary responses. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 1996;159:505–13. 10.2307/2983328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blakely T, Woodward A, Salmond C. Anonymous linkage of new zealand mortality and census data. Aust N Z J Public Health 2000;24:92–5. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hiscock R, Murray S, Brose LS, et al. Behavioural therapy for smoking cessation: the effectiveness of different intervention types for disadvantaged and affluent smokers. Addict Behav 2013;38:2787–96. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wogalter MS, Conzola VC, Smith-Jackson TL. Research-based guidelines for warning design and evaluation. Appl Ergon 2002;33:219–30. 10.1016/S0003-6870(02)00009-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, et al. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:173–90. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. European Commission. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Official Journal of the European Union 2014;L127:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 35. European Commission. Report on the public consultation on the possible revision of the Tobacco Products Directive (2001/37/EC). Health and Consumers Directorate-General – Directorate D – Health systems and products D4 – Substances of human origin and tobacco control, 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/consultation_report_en.pdf (accessed 10 Sep 2017).

- 36. Warner KE. The national and international regulatory environment in tobacco control. Public Health Res Pract 2015;25:e2531527 doi:10.17061/phrp2531527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ford A, Moodie C, MacKintosh AM, et al. Adolescent perceptions of cigarette appearance. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:464–8. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh A, et al. Are all cigarettes just the same? Female’s perceptions of slim, coloured, aromatized and capsule cigarettes. Health Educ Res 2015;30:1–12. 10.1093/her/cyu063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doxey J, Hammond D. Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tob Control 2011;20:353–60. 10.1136/tc.2010.038315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. White CM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, et al. The potential impact of plain packaging of cigarette products among Brazilian young women: an experimental study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:737 10.1186/1471-2458-12-737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kotnowski K, Fong GT, Gallopel-Morvan K, et al. The impact of cigarette packaging design among young females in canada: Findings from a discrete choice experiment. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1348–56. 10.1093/ntr/ntv114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoek J, Gendall P, Maubach N, et al. Strong public support for plain packaging of tobacco products. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012;36:405–7. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mahood G. Canadian tobacco package warning system. Tob Control 1995;4:10–14. 10.1136/tc.4.1.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.