Abstract

Introduction

Sustaining effective interventions in hospital environments is essential to improving health outcomes, and reducing research waste. Current evidence suggests many interventions are not sustained beyond their initial delivery. The reason for this failure remains unclear. Increasingly research is employing theoretical frameworks and models to identify critical factors that influence the implementation of interventions. However, little is known about the value of these frameworks on sustainability. The aim of this review is to examine the evidence regarding the use of theoretical frameworks to maximise effective intervention sustainability in hospital-based settings in order to better understand their role in supporting long-term intervention use.

Methods and analysis

Systematic review. We will systematically search the following databases: Medline, AMED, CINAHL, Embase and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE, HTA). We will also hand search relevant journals and will check the bibliographies of all included studies. Language and date limitations will be applied. We will include empirical studies that have used a theoretical framework (or model) and have explicitly reported the sustainability of an intervention (or programme). One reviewer will remove obviously irrelevant titles. The remaining abstracts and full-text articles will be screened by two independent reviewers to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Disagreements will be resolved by discussion, and may involve a third reviewer if required. Key study characteristics will be extracted (study design, population demographics, setting, evidence of sustained change, use of theoretical frameworks and any barriers or facilitators data reported) by one reviewer and cross-checked by another reviewer. Descriptive data will be tabulated within evidence tables, and key findings will be brought together within a narrative synthesis.

Ethics and dissemination

Formal ethical approval is not required as no primary data will be collected. Dissemination of results will be through peer-reviewed journal publications, presentation at an international conference and social media.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017081992.

Keywords: change management, quality in health care, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The findings from the review will provide a valuable addition to the evidence base around the use of frameworks to support sustainability.

The review will identify the barriers and facilitators that influence the delivery of sustained healthcare interventions in hospital-based settings.

A lack of consistent and complete reporting of sustainability in addition to a consensus on its definition may hinder our review findings.

Introduction

Sustaining the delivery of effective complex interventions is arguably one of the most significant challenges facing healthcare organisations today. The implementation of new interventions to improve both health and organisational outcomes has become commonplace.1–3 These interventions frequently target professional behaviours.4 5 Some of these interventions are mandated by policy directives, but many are not. Instead, the impetus behind their development and implementation often appears reactive to identified systemic weaknesses and calls for remedial action. One recent example of this is the ward-based improvement interventions6 that were developed following a series of high-profile public enquiries into the quality of UK healthcare systems.7 However, there is growing evidence that the implementation of such interventions are frequently not sustained. A recent study estimated that up to 60% of all newly implemented interventions stop being delivered a few years after their initial funding ceases.8

Failure to sustain new interventions can have considerable consequences, including the failure to deliver best practice,9 wasting limited resources10 and practitioners becoming cynical about the value of implementing new interventions eroding the trust between the people who develop complex interventions and those who deliver them.11

The importance of understanding how to improve the sustainability of intervention implementation is well documented.12–14 Previous reviews have examined factors that improve sustainability of interventions in the health sector.7 10 13 15–17 Wiltsey-Stirman et al 13 identified innovation characteristics (eg, fit and effectiveness of the intervention), context (eg, culture and leadership), capacity (eg, funding and resources) and processes and interactions (eg, shared decision-making and adaptation/alignment) as influences on sustainability. More recently, Willis et al 18 identified factors that impact on culture change and its influence on sustainability within healthcare organisations. Other reviews have developed frameworks to support the sustainment of public health interventions.10 19 Such frameworks aim to address the factors identified in the reviews as areas that impact on sustainability. These bodies of work have provided significant contributions to the implementation field. However, to date, there has been no review conducted addressing sustainability of hospital-based interventions.

Well-developed theories about the factors that influence implementation outcomes already exist.20 Such theoretical approaches provide an understanding of why the implementation of interventions can succeed or fail; and can provide strategies that can be adopted to improve the likelihood of successful implementation. Despite the contribution of theoretical frameworks to the understanding of some aspects of implementation, little attention has been given to issues of intervention sustainability; that is the enduring implementation of an intervention after its initial roll-out in practice.21 22 Therefore, we propose to conduct a systematic review of theoretical frameworks that have been used to address sustainability of interventions. We focus our review on hospital-based interventions as hospitals have been the focus for a series of implementation projects in recent years. They are challenging and complex environments. Understanding factors that lead to sustained implementation in hospital settings is therefore likely to be of considerable research and practice benefit.

Objectives

The overall aim of this review is to systematically search and synthesise evidence of the use of frameworks in the promotion of sustained intervention implementation in hospital-based interventions. We have three review objectives:

To identify, synthesise and appraise empirical studies that use/develop and test a theoretical framework to explore how hospital-based health (both physical and mental health) interventions are sustained in practice.

To identify and document the theories that are employed in implementing the sustained hospital-based interventions identified in (1).

To identify the barriers and facilitators that influence the delivery of sustained healthcare interventions in a hospital-based setting.

Methods and analysis

Design

We plan to conduct a systematic review and will report the data in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.23 Our protocol was developed using the PRISMA Protocol (PRISMA-P) checklist.24

Preliminary scoping work

In order to develop an informed, consensual research protocol, key preliminary scoping work was first completed. We employed an iterative-team approach while developing the protocol using the methodological steps outlined in Arksey and O’Malley.25 Detailed notes were kept for each meeting and were circulated to the team afterwards in order to ensure transparency and consensus.

Discussion between the research team led to consensus over:

Search strategy.

Refining the selection criteria.

Key definitions (eg, framework, sustainability, hospital-based).

Identifying and agreeing the frameworks that would be used to synthesise the data (eg, barriers and facilitators and theoretical frameworks).

The outcome of each of these discussions are reported in the following sections.

Information sources and search strategy

Search strategy

We plan to generate search terms using the following process:

Discussion with the research team to identify relevant terms using background literature that was judged to have relevance to the review. The search strategies, used in previous reviews of sustainability10 13 14 16–18 26 27 will be used to provide a list of potential search terms which will then be discussed by the research team (figure 1).

We will examine the search strategies and terms that are published in high-quality empirical studies on sustainability in order to further refine the search strategy.28–31 As part of our scoping work, the research team have agreed that terms such as ‘strategies’, ‘techniques’ and ‘approaches’ will not be included, as articles that use these terms, if omitted by the search strategy, will be identified through handsearching reference lists of included studies and key journals.

We will then combine key terms using a series of free-text terms and MEdical Subject Headings (MESH) for: (a) framework (eg, frameworks, theories, models), (b) sustainability (eg, durability, long-term implementation) and (c) hospital (eg, ward, patient).

Finally, we will trial the search using Medline database (Ovid) and refine the search terms if required before conducting the searches on the other electronic databases.

Figure 1.

A summary of the categories of implementation theories, models and frameworks described in Nilsen20 and the level of theoretical visibility reported in Bradbury-Jones et al.36

We will adapt the search strategy for each database as required, using Boolean operators and wildcards to account for variations across databases. Our search terms are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Topic | Search terms |

| Framework | theor* OR model OR models OR principle* OR construct* OR framework* |

| Sustainability | sustain* OR implement* OR long-term implement* OR long term implement* OR sustain* OR implement* OR long-term implement* OR long term implement* OR routini$ation OR discontinue* OR de-adoption OR deadoption OR durabil* OR institutionali$ation OR maintenance OR capacity building OR knowledge utili$ation |

| Hospital-based | hospital* OR inpatient* OR in-patient* OR ward* OR unit* |

Electronic searches

We will systematically search the following electronic databases from 1 January 2008:

Medline.

AMED.

CINAHL.

Embase.

Cochrane Library (eg, CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE, HTA).

We have applied a date restriction to the search, as the Medical Research Council (MRC) complex intervention framework was published in 2008,32 and it is likely that the most relevant studies to our review would have been conducted following the framework’s development.

Other searches

We will handsearch the Implementation Science journal. We will also hand-search the reference list of all included studies.

Eligibility criteria

Selection criteria for inclusion were purposefully wide. We plan to include studies that meet the following criteria:

Published in English from 1 January 2008.

Empirical studies relating to sustainability of an intervention or programme conducted in a secondary care hospital setting.

Studies should focus on sustainability intended to improve patient care and must incorporate a framework or theory or model.

We will exclude studies that are not published in English or are not peer-reviewed publications. We will not include any non-research study designs (eg, unstructured reviews or overviews, theoretical papers, commentaries or opinion papers, protocol, case study, editorial, audit, letter).

We plan to exclude studies that are not conducted in hospital-based settings. In the case of studies performed across multiple settings, studies will be excluded where results pertaining to the hospital setting are not clearly identifiable. In addition, if the service provided is regarded as an outpatient clinic, then the study will also be excluded.

We will not include any studies that do not discuss a specific intervention or programme (ie, solely reports programmes at a general systems level) or only discusses sustainability prospectively (ie, an empirical study has not been carried out). Finally, we will not include studies where sustainability is not a specific concern of the study (ie, it is concerned only with adoption and initial implementation of the intervention/programme) and does not make any reference to frameworks, theories or models that relate to sustainability.

Definition of key terms

We will use the following operational definitions to support the application of the selection criteria:

Sustainability

Over the last 20 years, significant effort has been invested in an attempt to summarise the use of various definitions of sustainability to produce a single definition of the term.33–35 However, a universally accepted definition is still lacking. Consequently, sustainability has been variously described as maintenance, continuation, institutionalisation, routinisation, durability, maintenance and stability.13 16 27

The review authors considered a number of definitions from the published literature. It was clear from initial discussions that we would need to employ a broad definition of sustainability, and the final consensus was that the review should be guided by the recent work described in Moore et al.34

Moore et al identified 209 articles from four knowledge syntheses of sustainability. Definitions of sustainability were given in 24 (11.5%) of these articles which were used by Moore et al to create a revised definition comprising five key constructs:

After a defined period of time.

The programme, clinical intervention and/or implementation strategies continue to be delivered.

Individual behaviour change is maintained.

The programme and individual behaviour change may evolve or adapt.

Continuing to produce benefits for individuals/systems.

We acknowledge that this definition may not be relevant or applicable to all of the different hospital settings. Furthermore, aspects of the definition may be difficult to operationalise particularly if the information is not fully reported within the study (eg, ‘defined’ period of time). Therefore, it was decided that the review team will judge each study against each of the constructs, and document where the information is missing, highlighting any gaps in the evidence base.

Hospital-based intervention

We defined a hospital-based intervention as any intervention that is delivered within a secondary care hospital environment, is aimed at improving patient care, and that directly involves care delivery to patients or staff, but not including ambulatory care, virtual or laboratory-based interventions.

Framework

Theories and models are widely used in implementation science. Consequently, we have decided to use the taxonomy of theories, models and frameworks developed by Nilsen, in which a framework is described as a structure that seeks to define factors which influence implementation outcomes.20

Using Nilsen’s taxonomy, we will classify each framework into one of the following five categories:

Process model.

Determinant framework.

Classic theory.

Implementation theory.

Evaluation framework.

We will also assess and report each paper on the degree of theoretical visibility as described by Bradbury-Jones et al.36 Figure 1 summarises how theories, models and frameworks will be categorised and coded according to typology20 and level of theoretical visibility.36

Study selection

One reviewer will run the search strategy, read the titles of the references and eliminate any obviously irrelevant studies. Abstracts will be independently screened by two reviewers who will rank each abstract based on the selection criteria as relevant, irrelevant or unclear. Abstracts that are ranked as irrelevant by both reviewers will be excluded at this stage. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. The full text for the remaining (those ranked as relevant or unclear) will be obtained, and reviewed by two review authors against the predefined selection criteria. Consensus meetings will be organised to discuss any disagreements.

Data extraction and coding

Data extraction

A standardised, prepiloted form will be used to extract data from the included studies for assessment of study quality and evidence synthesis.

We will extract the following information:

Study characteristics (author, date of publication, country, aims, study design).

Study population.

Participant demographics (sample size, patient group, details of healthcare professional/staffing groups involved including any details of their length of service, job role).

Study setting and other relevant contextual information.

Details of the intervention and interventionist (using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication guidelines37).

Any comparison conditions.

Evidence of sustained change (eg, how long the intervention has been delivered on the ward; any associations that the authors report between intervention and sustained effectiveness).

Framework employed (including the reason for selection).

Outcomes measures.

Key findings.

One member of the review team will extract the data from relevant publications into the spreadsheet, and a second will check the data entry. Any differences in the assessment of quality will be resolved via discussion between these authors, and if necessary, referred to a third reviewer for a final decision.

Barriers and facilitators that are identified as important in the delivery of the hospital-based intervention will be extracted by two independent reviewers, using predefined lists outlined in more detail below.

Coding for barriers and facilitators

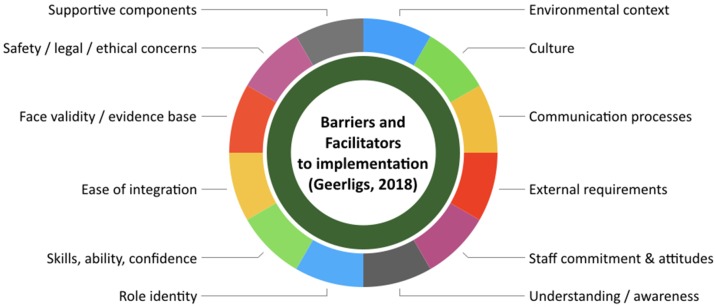

A single, comprehensive tool for identifying the barriers and facilitators for sustained long-term intervention is currently lacking. Therefore, we propose to use a deductive approach to identify and code the barriers and facilitators using a predefined list of factors based on an amalgam of published frameworks in the fields of implementation science and patient safety. These include the Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE) framework,38 Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation,39 Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework40 and Sustainability constructs in Healthcare.41 figures 2–5 show each of the domains that are currently described within each of the four implementation frameworks.38–41 Barriers or facilitators that cannot be categorised using the predefined codes will be coded as ‘other’, and we will use an inductive coding approach to develop themes and subthemes from this additional data.

Figure 2.

A graphical summary of the different domains that are used to categorise the barriers and facilitators across the Geerligs et al 39 framework.

Figure 3.

A graphical summary of the different domains that are used to categorise the barriers and facilitators across the Lawton et al 40 framework.

Figure 4.

A graphical summary of the different domains that are used to categorise the barriers and facilitators across the Lennox et al 41 framework.

Figure 5.

A graphical summary of the different domains that are used to categorise barriers and facilitators across the SURE38 framework.

Methodological quality assessment

Study quality will be assessed independently by two reviewers, using tools appropriate to the design of the study (ie, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,42 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool43 and Standards for Quality Improving Reporting Excellence44).

Data synthesis

Descriptive data (ie, year, country, professional groups involved, hospital setting and other contextual factors) will be tabulated within evidence tables. Due to the potential heterogeneity between studies and outcomes, we do not plan to conduct a meta-analysis. Key findings will be brought together within a narrative synthesis.

Data specifically relating to the barriers and facilitators will be grouped to derive common themes, taking into consideration the theoretical framework and sustainability. These themes will be organised to provide tabular and narrative summarises of key characteristics.

Patient and public involvement

As the review is analysing secondary data, no patient and public involvement has been involved in the protocol. However, we do plan to involve patients in the later stages of the wider project this review will inform.

Ethics and dissemination

We intend to disseminate the review findings via social media and will present our work at an international peer-reviewed conference. In addition, we aim to publish two peer-reviewed journal publications: one detailing the review findings and a second, discussion piece, reflecting on barriers and facilitators and how these are addressed by frameworks aimed at supporting sustainability.

Conclusions

This systematic review will provide a better understanding of factors that promote or inhibit sustained intervention implementation in hospital-based settings. It is unlikely that there will be a singular contributing factor that is responsible for the longer-term success of any intervention across the diverse settings. However, it is essential to identify and analyse these factors in order to improve the design of hospital-based improvement interventions to include factors that are likely to increase their sustainability. Furthermore, learning about the factors that increase the likelihood of interventions being sustained in practice will provide valuable information for policy-makers, healthcare managers and clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JC, PC and EASD conceived the idea, planned and designed the study protocol. JC, PC, ED, AN and EASD drafted the protocol and revised the protocol following author comments. AN and ED revised the paper critically. PC devised the figures. All authors have contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government. Ref: CGA/17/26.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: No ethical approval is required for the review as it does not involve primary data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1. Dombrowski SU, Campbell P, Frost H, et al. Interventions for sustained healthcare professional behaviour change: a protocol for an overview of reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:173 10.1186/s13643-016-0355-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flodgren G, Pomey MP, Taber SA, et al. Effectiveness of external inspection of compliance with standards in improving healthcare organisation behaviour, healthcare professional behaviour or patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;11:CD008992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenhalgh T. Role of routines in collaborative work in healthcare organisations. BMJ 2008;337:a2448 10.1136/bmj.a2448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson MJ, May CR. Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: what interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008592 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Presseau J, Mutsaers B, Al-Jaishi AA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare professional behaviour change in clinical trials using the Theoretical Domains Framework: a case study of a trial of individualized temperature-reduced haemodialysis. Trials 2017;18:227 10.1186/s13063-017-1965-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monitor. Closing the NHS funding gap: how to get better value healthcare for patients, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Savaya R, Elsworth G, Rogers P. Projected sustainability of innovative social programs. Eval Rev 2009;33:189–205. 10.1177/0193841X08322860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Addressing the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care: a systematic review of reviews protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005548 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci 2013;8:15 10.1186/1748-5908-8-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: service provider perspectives. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34:411–9. 10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doyle C, Howe C, Woodcock T, et al. Making change last: applying the NHS institute for innovation and improvement sustainability model to healthcare improvement. Implement Sci 2013;8:127 10.1186/1748-5908-8-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 2012;7:17 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implementation Science 2013;8 10.1186/1748-5908-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwelunmor J, Blackstone S, Veira D, et al. Toward the sustainability of health interventions implemented in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Implement Sci 2016;11:43 10.1186/s13012-016-0392-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Cardoso R, et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2016;11:55 10.1186/s13012-016-0421-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ament SM, de Groot JJ, Maessen JM, et al. Sustainability of professionals' adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008073 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Willis CD, Saul J, Bevan H, et al. Sustaining organizational culture change in health systems. J Health Organ Manag 2016;30:2–30. 10.1108/JHOM-07-2014-0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whelan J, Love P, Pettman T, et al. Cochrane update: Predicting sustainability of intervention effects in public health evidence: identifying key elements to provide guidance. J Public Health 2014;36:347–51. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 2015;10:53 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haines A, Kuruvilla S, Borchert M. Bridging the implementation gap between knowledge and action for health. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:724–31. discussion 32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013;8:117 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet 2008;372:1579–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61659-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parand A, Benn J, Burnett S, et al. Strategies for sustaining a quality improvement collaborative and its patient safety gains. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:380–90. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Savant AP, Britton LJ, Petren K, et al. Sustained improvement in nutritional outcomes at two paediatric cystic fibrosis centres after quality improvement collaboratives. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23(Suppl 1):i81–i89. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van Rostenberghe H, Short J, Ramli N, et al. A psychologist-led educational intervention results in a sustained reduction in neonatal intensive care unit infections. Front Pediatr 2014;2:115 10.3389/fped.2014.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bridges J, May C, Fuller A, et al. Optimising impact and sustainability: a qualitative process evaluation of a complex intervention targeted at compassionate care. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:970–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res 1998;13:87–108. 10.1093/her/13.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, et al. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci 2017;12:110 10.1186/s13012-017-0637-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? a review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval 2005;26:320–47. 10.1177/1098214005278752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, Herber O. How theory is used and articulated in qualitative research: development of a new typology. Soc Sci Med 2014;120:135–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. The Sure Collaboration. SURE Guides for preparing and using evidence-based policy briefs: 5 identifying and addressing barriers to implementing policy options v2.1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Geerligs L, Rankin NM, Shepherd HL, et al. Hospital-based interventions: a systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement Sci 2018;13:36 10.1186/s13012-018-0726-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lawton R, McEachan RR, Giles SJ, et al. Development of an evidence-based framework of factors contributing to patient safety incidents in hospital settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:369–80. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci 2018;13:27 10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. CASP, 2018. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklists UK. https://casp-uk.net/ - !casp-tools-checklists/c18f82018

- 43. Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:529–46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. SQUIRE, 2018. Standards for QUality Improvment Reporting Excellence. http://www.squire-statement.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.