Abstract

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) requires patients and caregivers to invest in self-care and self-management of their disease. We aimed to describe the work for adult patients that follows from these investments and develop an understanding of burden of treatment (BoT).

Methods

Systematic review of qualitative primary studies that builds on EXPERTS1 Protocol, PROSPERO registration number: CRD42014014547. We included research published in English, Spanish and Portuguese, from 2000 to present, describing experience of illness and healthcare of people with CKD and caregivers. Searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, Scopus, Scientific Electronic Library Online and Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal. Content was analysed with theoretical framework using middle-range theories.

Results

Searches resulted in 260 studies from 30 countries (5115 patients and 1071 carers). Socioeconomic status was central to the experience of CKD, especially in its advanced stages when renal replacement treatment is necessary. Unfunded healthcare was fragmented and of indeterminate duration, with patients often depending on emergency care. Treatment could lead to unemployment, and in turn, to uninsurance or underinsurance. Patients feared catastrophic events because of diminished financial capacity and made strenuous efforts to prevent them. Transportation to and from haemodialysis centre, with variable availability and cost, was a common problem, aggravated for patients in non-urban areas, or with young children, and low resources. Additional work for those uninsured or underinsured included fund-raising. Transplanted patients needed to manage finances and responsibilities in an uncertain context. Information on the disease, treatment options and immunosuppressants side effects was a widespread problem.

Conclusions

Being a person with end-stage kidney disease always implied high burden, time-consuming, invasive and exhausting tasks, impacting on all aspects of patients' and caregivers’ lives. Further research on BoT could inform healthcare professionals and policy makers about factors that shape patients’ trajectories and contribute towards a better illness experience for those living with CKD.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42014014547.

Keywords: treatment burden, chronic kidney disease, systematic review, haemodialysis, kidney transplant

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We analysed data with a coding framework supported by middle-range theories to understand the work involved in being a person with chronic kidney disease.

Comprehensive inclusion of publications in English, Spanish and Portuguese, which may enhance the transferability of our findings.

The variety of methodologies, quality of reporting and heterogeneity of perspectives make synthesis difficult.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) contributes significantly to global morbidity and mortality.1–4 Even in its early stages, the risk of death, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular disorders, hospitalisation, reduced health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation is increased.1–6

Worldwide, about 500 million people are affected by CKD; about 80% of these live in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC); an estimated 3 million people with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) with either dialysis or transplantation.1 7 8 The number of people receiving RRT is increasing and will more than double by 2030, but a significant number of people without access to this type of live-saving treatment will remain.9 In 2010, at least 2.28 million people might have died because of lack of access to RRT, mostly in LMIC in Asia, Africa and Latin America.9

Much is now known about the pathophysiological and treatment trajectories of CKD, and about the associated burden of symptoms experienced by patients. More recently, there has been increasing interest in the way that complex long-term conditions require patients and their carers to invest in self-care and self-management of their disease.10–15 The work for patients and carers that follows from these investments, including medication management, medical visits, laboratory tests, lifestyle changes and monitoring in addition to the activities done as part of life, is here termed burden of treatment (BoT), which adds to the burden of symptoms (BoS).10 13 16 Research on BoT has focused on long-term conditions such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure, with the development of analytic framework and patient-created taxonomies.10 16–27 Patients and carers are expected to actively participate in managing both index conditions and comorbidities and, depending on their resources or lack thereof, they often need to negotiate or renegotiate the responsibilities that healthcare providers and healthcare systems assign to them.13 28 29 Patients' and carers’ experience in managing the disease and its treatment, including their choices and expectations, is affected by structural, relational and resilience factors; the interactions among these factors remain understudied.30 The aim of this study is to develop specific understanding of treatment burden experienced by people with CKD and ESKD extending it to experiences of uninsured and underinsured patients in LMIC.

Methods

This is a systematic review of primary qualitative studies, which builds on the published EXPERTS1 Protocol and its meta-review of qualitative reviews.30 31 PROSPERO registration number is CRD42014014547. This review follows the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research framework.32 We interrogated a subset of qualitative primary research papers concerned with CKD identified by EXPERTS1 qualitative meta-review to understand the dynamics of patient experience of complexity and treatment burden in long-term life-limiting conditions. EXPERTS1 search was updated and expanded to Spanish and Portuguese language literature.

Eligibility, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria for study inclusion were developed using the participants, interventions, comparators and outcomes framework (table 1). Inclusion criteria were primary qualitative and mixed-method studies of adult patients diagnosed with CKD in any stage and their formal or informal carers; in any type of treatment or healthcare provision; not limited to comparative studies; with qualitative data on the patients' and carers’ experiences on any aspect of CKD, in any stage, and its treatments; in English, Spanish and Portuguese. Following the EXPERTS1 protocol, studies were excluded if they were of other EXPERTS1 index conditions; if they reported results of treatments, interventions, tests or surveys; were guidelines, discussions of the literature or editorials, notes, news, letters and case reports; if the experiences described by patients and carers could not be clearly discriminated.31 Studies describing experiences of children with CKD were excluded because their BoT may be significantly different from that of adult patients. The year of publication 2000 onwards was established to include current treatments.

Table 1.

PICO criteria for including studies

| Population | Patients of at least 18 years of age, diagnosed with CKD, and formal and informal carers. |

| Intervention | Experiences of healthcare provision, any type of treatment for CKD. |

| Comparator | Not limited to comparator studies. |

| Outcomes | Qualitative data on patients' and carers’ experiences of care for those patients with CKD. |

| Study type | Primary studies, qualitative or mixed methods studies. |

| Time | From 2000 to present. |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; PICO, participants, interventions, comparators and outcomes.

Study selection

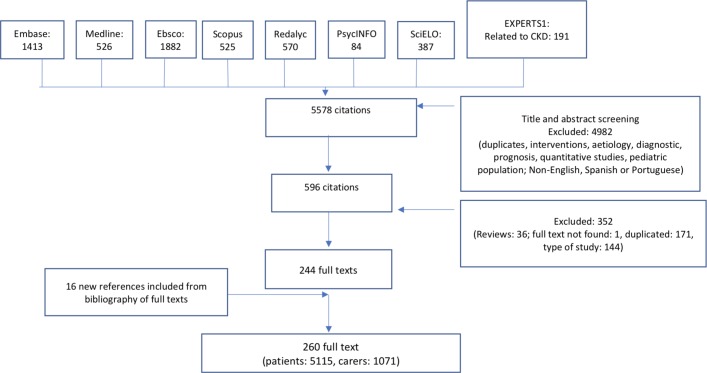

A first search for the EXPERTS1 meta-review was conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and Scopus. For this review, searches were updated using the same databases and expanded to include studies published in Spanish and Portuguese with additional searches in the Iberoamerican databases Scientific Electronic Library Online and Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal. Searches were completed by April 2017 and identified papers published between 1 January 2000 and March 2017. Search strategy is included in supplementary appendix 1. For a first set of studies, titles and abstracts were independently screened by AC, MM and CRM, disagreements resolved by JH. Full-text papers (n=1238) were obtained and screened by JH, KAL and MM; disagreements resolved by KH or AC. Of 606 articles, 191 were related to CKD. For a second set, updated results in English and studies in Spanish and Portuguese were screened by JR, JPA, disagreements resolved by FC. Two authors (JR, JPA) assessed papers against the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative research checklist.33 As there is no accepted criteria for the exclusion of qualitative studies-based appraisal score, we did not exclude studies based on quality. See figure 1 for screening and selection process.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of screening and selection process. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

bmjopen-2018-023507supp001.pdf (21.9KB, pdf)

Data extraction and analysis

Data outlining study characteristics are shown in table 2. Manuscripts were entered into Atlas.Ti V.7.5.12 (Scientific Software Development GmbH). The results sections and participant quotations of the primary studies were analysed line-by-line using directed content analysis, sometimes called framework analysis.34 The coding frame drew on concepts from the Burden of Treatment Theory and the Cognitive Authority Theory.18–21 29 35 36 Coding was conducted by JR and CRM, with a third party involved for disagreements (JPA), and reviewed and discussed by two researchers (AC, MM). Refinement of the coding frame and analysis was iterative, codes were identified or merged reading the result sections of primary studies and consulting the theoretical framework. Investigator triangulation (comparison of results of two or more researchers) was used to capture relevant issues, reflect participants’ experience as reported and ensure the credibility of the findings.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Year | Country | Setting | Patients | Carers | Type of patient | Data collection | Data analysis reported |

| Aasen et al 107 | 2012 | Norway | 5 H, East, West | 11 | ESKD | Interviews | Critical discourse | |

| Aasen et al 246 | 2012 | Norway | 5 H, East, West | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Critical discourse | |

| Aasen287 | 2012 | Norway | 5 H, East, West | 11 | 17 | ESKD | Interviews | Critical discourse |

| Al-Arabi104 | 2006 | USA | 1 C, Southwest | 80 | ESKD | Interviews | Naturalistic inquiry, thematic | |

| Allen et al 173 | 2011 | Canada | 1 H, urban | 7 | ESKD | Ethnographic observations, interviews | Participatory action, thematic | |

| Allen et al 64 | 2015 | Canada | 2 H | 6 | 11 | ESKD | Ethnographic observations, interviews | Thematic |

| Anderson et al 77 | 2008 | Australia | 9 H, 17 C | 241 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Anderson et al 53 | 2012 | Australia | 9 H, 17 C | 241 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Arslan and Ege200 | 2009 | Turkey | 1 H, Kenya | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Ashby et al 38 | 2005 | Australia | 2 H, Melbourne | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Avril-Sephula et al 118 | 2014 | UK | 1 H, North | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Axelsson et al 187 | 2012 | Sweden | 2 H, 2 C | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological, hermeneutical | |

| Axelsson et al 136 | 2012 | Sweden | 2 H, 2 C | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological, hermeneutical | |

| Axelsson et al 134 | 2015 | Sweden | 2 H, 1 C, urban | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Bailey et al 235 | 2015 | UK | Bristol | 32 | Transplanted | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Bailey et al 39 | 2016 | UK | Bristol | 13 | Transplanted | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Baillie and Lankshear156 | 2015 | UK | Wales | 16 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Baillie and Lankshear157 | 2015 | UK | Wales | 16 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Barbosa and Valadares145 | 2009 | Brazil | 1 C, Rio de Janeiro | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Bath et al 252 | 2003 | UK | South | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Beanlands et al 210 | 2005 | Canada | Ontario | 37 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Bennett et al 197 | 2013 | Australia | 4 C | 9 | 2 | ESKD | Interviews facilitated by images | Thematic |

| Blogg and Hyde69 | 2008 | Australia | Urban | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Ethnographic | |

| Boaz and Morgan175 | 2014 | UK | Rural, urban | 25 | Transplanted | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Bourbonnais and Tousignant105 | 2012 | Canada | 1 H | 25 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Bridger238 | 2009 | UK | GP, South | 23 | CKD | Interviews, drawings, journals | Grounded theory | |

| Bristowe et al 126 | 2015 | UK | 2 C, London | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| de Brito-Ashurst et al 121 | 2011 | UK | London | 20 | CKD | Focus groups, vignettes and diaries | Thematic | |

| Browne et al 226 | 2016 | USA | South | 40 | ESKD | Focus groups | Content | |

| Buldukoglu et al 186 | 2005 | Turkey | Antalya | 40 | Transplanted | Open-ended questions | Constant comparison | |

| Burnette and Kickett78 | 2009 | Australia | 1 C, Perth | 6 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Cadena et al 154 | 2015 | Mexico | Coyotepec, Mexico | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological | |

| Calvey and Mee146 | 2011 | Ireland | NA | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Calvinl 251 | 2004 | USA | 3 C, Texas | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Calvin et al 292 | 2014 | USA | Texas | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative, Glaserian | |

| Campos and Turato234 | 2003 | Brazil | 1 H, Sao Paulo | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Campos and Turato87 | 2010 | Brazil | 1 H, Sao Paulo | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Campos et al 88 | 2015 | Brazil | H, C, Paraná | 23 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Cases et al 279 | 2011 | UK | NA | 6 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Cervantes et al 52 | 2017 | USA | 1 H, Colorado | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Chatrung et al 188 | 2015 | USA | California | 8 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Chenitz et al 86 | 2014 | USA | 4 C, Pennsylvania | 30 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Chiaranai40 | 2016 | Thailand | 1 H | 26 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Cho and Shin41 | 2016 | South Korea | 1 H, South | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Chong et al 164 | 2016 | South Korea | 1 H, South | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Clarkson and Robinson106 | 2010 | USA | Oklahoma | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Costa et al 198 | 2014 | Brazil | 3 H, Paraíba | 26 | ESKD | Interviews | Lexical | |

| Costantini et al 92 | 2008 | Canada | Ontario | 14 | CKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Cox et al 148 | 2016 | USA | 6 C, New Mexico | 50 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretive description | |

| Cramm et al 219 | 2015 | The Netherlands | 1 H, Rotterdam | 15 | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Factor analysis, Q methodology |

| Cristóvao et al 113 | 2013 | Portugal | 1 C, Lisbon | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Crowley-Matoka et al 83 | 2005 | Mexico | 2 prog, Guadalajara | 50 | Transplanted | Interviews | NA | |

| Curtin et al 265 | 2001 | USA | Diverse | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Curtin et al 264 | 2002 | USA | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | ||

| da Silva et al 103 | 2016 | Brazil | 1 C, Northeast | 30 | ESKD | Interviews | Content and thematic | |

| da Silva et al 338 | 2011 | Brazil | 1 H, Rio Grande do Sul | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Qualitative | |

| Darrell et al 281 | 2016 | USA | 1 H | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Giorgi’s method | |

| Davison et al 231 | 2006 | Canada | Alberta | 24 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison, iterative | |

| Davison et al 291 | 2006 | Canada | 1 H | 19 | ESKD | Interviews | inductive | |

| de Brito et al 89 | 2015 | Brazil | 1 H, Minas Gerais | 50 | Transplanted | Interviews | Collective subject technique | |

| de Rosenroll et al 277 | 2013 | Canada | 1 H | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Dekkers et al 42 | 2005 | The Netherlands | 2 C | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| DePasquale et al 221 | 2013 | USA | NP, 1 C | 68 | 62 | CKD | Group interviews | Mixed method |

| dos Reis et al 155 | 2008 | Brazil | 1 H, Sao Paulo | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| dos Santos et al 162 | 2011 | Brazil | Rio de Janeiro | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| dos Santos et al 259 | 2015 | Brazil | 3 NP, Rio Grande do Sul | 20 | Transplanted | Interviews | Critical incident | |

| Ekelund et al 43 | 2010 | Sweden | 1 C, South | 39 | 21 | ESKD | Interviews | Content |

| Erlang et al 203 | 2015 | Denmark | 1 H | 9 | CKD (predialysis) | Interviews | Systematic text condensation | |

| Eslami et al 214 | 2016 | Iran | 4 C, Isfahan | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Finnegan-John et al 90 | 2013 | UK | 1 trust, London | 118 | 12 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic |

| Flores et al 165 | 2004 | Brazil | 1 H, Rio Grande do Sul | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Fraguas et al 37 | 2008 | Brazil | 2 H, Minas Gerais | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Ghadami et al 239 | 2012 | Iran | 1 charity, Isfahan | 15 | Transplanted | Interviews | Content | |

| Giles et al 159 | 2003 | Canada | 1 H, urban | 4 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Giles et al 160 | 2005 | Canada | 4 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | ||

| Goff et al 288 | 2015 | USA | New Mexico | 13 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Goldane et al 176 | 2011 | USA | 1 C | 39 | Transplanted | Focus groups and interviews | Iterative analysis | |

| Gordon et al 180 | 2007 | USA | 20 | Transplanted | Diary entries | Thematic | ||

| Gordon et al 84 | 2009 | USA | 2 H, Illinois, New York | 82 | Transplanted | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Gricio et al 114 | 2009 | Brazil | 1 H, Sao Paulo | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Gullick et al 339 | 2016 | Australia | 1 H, Sydney | 11 | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Hermeneutic interpretation |

| Hagren et al 282 | 2001 | Sweden | 1 H | 15 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Hagren et al 115 | 2005 | Sweden | 3 H | 41 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Hain et al 189 | 2011 | USA | 6 C, Southeast | 56 | ESKD | Interviews | Story inquiry method | |

| Hanson et al 70 | 2016 | Australia | 1 C, West | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Harrington et al 283 | 2016 | UK | 8 H | 24 | Transplanted | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Harwood et al 270 | 2014 | Canada | 1 H | 13 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Harwood et al 248 | 2005 | UK | 1 H, London | 11 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Haspeslagh et al 240 | 2013 | Belgium | 1 H, Leuven | 31 | Transplanted | Interviews and questionnaires | Thematic | |

| Heiwe et al 137 | 2003 | Sweden | 1 H, Karolinska | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Contextual | |

| Heiwe et al 140 | 2004 | Sweden | 1 H, Karolinska | 16 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Contextual | |

| Herbias et al 116 | 2016 | Chile | 1 C, Santiago | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Streubert’s method | |

| Herlin et al 284 | 2010 | Sweden | 3 C | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Giorgi’s method | |

| Hollingdale et al 227 | 2008 | UK | 20 | CKD/ESKD | Focus groups | Framework approach | ||

| Hong et al 120 | 2017 | Singapore | 1 H | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Horigan et al 138 | 2013 | USA | 1 C, Mid-Atlantic | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Hutchison et al 290 | 2017 | Canada | 1 clinic, urban | 9 | 16 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Interpretive description |

| Iles-Smith et al 232 | 2005 | UK | 1 C, Manchester | 10 | CKD (predialysis) | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Johnston et al 128 | 2012 | UK | 1 trust, London | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Kaba et al 340 | 2007 | Greece | 2 H, Athens | 23 | ESKD | Interviews | Qualitative | |

| Kahn et al 35 | 2015 | USA | 2 NP, New York | 34 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Karamanidou et al 15 | 2014 | UK | 1 C, London | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative, phenomenological | |

| Kazley et al 44 | 2015 | USA | 1 C, Southeast | 20 | CKD/ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Keeping et al 73 | 2001 | Canada | East | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Kierans et al 167 | 2001 | Ireland | 5 | ESKD | Interviews, life stories | Phenomenological | ||

| Kierans et al 166 | 2005 | Ireland | 5 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | ||

| Kierans et al 125 | 2013 | Mexico | 1 H, Jalisco | 51 | 87 | CKD/ESKD, transplanted | Interviews, observation* | Ethnographic approach |

| King et al 91 | 2002 | UK | 1 C | 22 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Template approach | |

| Knihs et al 168 | 2013 | Brazil | 1 C, South | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Krespi-Boothby et al 147 | 2004 | UK | 1 H, 4 C | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Krespi-Boothby et al 151 | 2013 | UK | 1 H, 4 C | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Template approach | |

| Ladin et al 202 | 2016 | USA | 2 C, Massachusetts | 23 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Ladin et al 269 | 2017 | USA | 2 C, Massachusetts | 31 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic Nutbeam’s framework | |

| Landreneau et al 274 | 2006 | USA | 1 C, 1 NP, South | 6 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Landreneau et al 278 | 2007 | USA | 2 C, South | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Lawrence et al 169 | 2013 | UK | 1 C | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Conceptual and categorical | |

| Lederer et al 266 | 2015 | USA | 1 C | 32 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Lee et al 223 | 2008 | Denmark | Diverse | 27 | 18 | ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic |

| Lee et al 45 | 2016 | Singapore | 1 organisation | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Lenci et al 256 | 2012 | USA | 4 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | ||

| Leung et al 181 | 2007 | Hong Kong | 1 C | 12 | Transplanted | Interviews | Content | |

| Lewis et al 285 | 2015 | UK | 14 H | 40 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Lin et al 190 | 2015 | Taiwan | 1 C, S, rural | 15 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Lindberg et al 46 | 2008 | Sweden | 1 C, mid-country | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Lindberg et al 262 | 2013 | Sweden | 1 C, mid-country | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Lindsay et al 280 | 2014 | Australia | 1 C, Sydney | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Llewellyn et al 271 | 2014 | UK | 4 C, London | 19 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Lo et al 129 | 2016 | Australia | 4 H, Melbourne, Sydney | 58 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic | |

| Lopes et al 170 | 2014 | Brazil | 1 C, Santa Catarina | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative | |

| Lopez-Vargas et al 94 | 2014 | Australia | 3 C, New South Wales | 38 | CKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Lopez-Vargas et al 93 | 2016 | Australia | 3 C, New South Wales | 38 | CKD/ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Lovink et al 217 | 2015 | The Netherlands | 1 C | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Low et al 161 | 2014 | UK | 5 C, Southeast | 26 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Machado et al 149 | 2003 | Brazil | Sao Paulo | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Discourse | |

| Marques et al 228 | 2014 | Brazil | Paraná | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Martin-McDonald et al 194 | 2003 | Australia | 5 C | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Martin-McDonald et al 195 | 2003 | Australia | 1 C | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Mason et al 95 | 2007 | UK | 1 C | 9 | 5 | CKD | Focus groups | Framework approach |

| McCarthy et al 163 | 2010 | Australia | 1 H | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Sequential | |

| McKillop et al 267 | 2013 | UK | Clinics | 10 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Mercado-Martínez et al 49 | 2014 | Mexico | Jalisco, San Luis Potosí | 21 | Transplanted | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Mercado-Martínez et al 48 | 2015 | Brazil | 1 H, South | 11 | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Content |

| Mercado-Martínez et al 47 | 2015 | Mexico | Public H and institutions, Jalisco | 37 | 50 | ESKD | Interviews | Content |

| Mitchell et al 205 | 2009 | UK | 1 C | 10 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Molzahn et al 294 | 2012 | Canada | Middle size city | 14 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Moran et al 204 | 2009 | Ireland | 1 H | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretive | |

| Moran et al 150 | 2009 | Ireland | 1 H | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretive | |

| Moran et al 133 | 2011 | Ireland | H | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative | |

| Morton et al 79 | 2010 | Australia | Diverse | 95 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Muduma et al 96 | 2016 | UK | 2 C | 37 | Transplanted | Focus groups | Qualitative | |

| Nagpal et al 218 | 2017 | USA | 1 C, New York | 36 | ESKD | Interviews | Coding | |

| Namiki et al 220 | 2010 | Australia | 1 H | 4 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Niu et al 196 | 2017 | China | 1 C, Jiangsu | 23 | ESKD | Interviews | Continuous comparison | |

| Nobahar et al 67 | 2016 | Iran | 1 H, Semnan | 8 | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Graneheim Lundman content |

| Nobahar et al 68 | 2016 | Iran | 1 H, Semnan | 8 | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Granheim and Lundman’s approach |

| Noble et al 293 | 2009 | UK | 1 service, London | 30 | 17 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison |

| Noble et al 98 | 2010 | UK | 1 service, London | 30 | 17 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison |

| Noble et al 97 | 2012 | UK | 1 service | 19 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Nygardh et al 289 | 2011 | Sweden | 1 C, South | 12 | CKD (predialysis) | Interviews | Content | |

| Nygardh et al 236 | 2011 | Sweden | 1 C, South | 20 | CKD | Interviews | Latent content | |

| Malheiro Oliveira et al 209 | 2012 | Brazil | Bahia | 19 | ESKD | Interviews | Categorical | |

| Orr et al 182 | 2007 | UK | 1 C | 26 | Transplanted | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Orr et al 183 | 2007 | UK | 1 C | 26 | Transplanted | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Oyegbile et al 65 | 2016 | Nigeria | 2 H, Southwest | 15 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Pelletier-Hibbert et al 286 | 2001 | Canada | East | 41 | ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Piccoli et al 224 | 2010 | Italy | 1 H | 12 | CKD/ESKD, transplanted | Focus groups | Not clear | |

| Pietrovski et al 208 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 H, Paraná | 15 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Pilger et al 225 | 2010 | Brazil | 1 C, Paraná | 22 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Polaschek et al 54 | 2003 | New Zealand | 1 C | 6 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Polaschek et al 55 | 2006 | New Zealand | 1 regional department | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Polaschek et al 56 | 2007 | New Zealand | 1 regional department | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Prieto et al 130 | 2011 | Spain | Andalusia | 22 | ESKD | Interviews | Discourse | |

| Rabiei et al 141 | 2015 | Iran | Isfahan | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Ravenscroft et al 260 | 2005 | Canada | 3 C | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Inductive | |

| Reid et al 268 | 2012 | UK | 1 C, clinics | 11 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Reta et al 131 | 2014 | Spain | 1 H, Araba | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Richard et al 108 | 2010 | USA | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Cultural negotiation model framework | ||

| Rifkin et al 99 | 2010 | USA | 1 C | 20 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Rix et al 58 | 2014 | Australia | New South Wales, rural | 18 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Rix et al 57 | 2015 | Australia | New South Wales, rural | 18 | 29 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Rodrigues et al 191 | 2011 | Brazil | 1 C, South | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Categorical | |

| Ros et al 244 | 2012 | USA | 1 H, Maryland | 19 | ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Roso et al 119 | 2013 | Brazil | 1 H, South | 15 | ESKD | Narrative interviews | Thematic | |

| Russ et al 229 | 2005 | USA | 2 C, California | 43 | ESKD | Interviews | Anthropologic study | |

| Russell et al 241 | 2003 | USA | 1 C, Midwest | 16 | Transplanted | Interviews | Constant comparison | |

| Rygh et al 71 | 2012 | Norway | North | 11 | ESKD | Interviews | Inductive, actor’s point of view | |

| Sadala et al 72 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 H | 19 | ESKD | Narrative interviews | Phenomenological, hermeneutical | |

| Sahaf et al 222 | 2017 | Iran | 2 hour, Sari | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | van Manen’s thematic | |

| Salvalaggio et al 82 | 2003 | Canada | 1 H, Ontario | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Immersion/crystalisation | |

| Schell et al 272 | 2012 | USA | 1 university system, 1 NP, North Carolina | 29 | 11 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic |

| Schipper et al 184 | 2014 | The Netherlands | 5 H | 30 | Transplanted | Focus groups and interviews | Thematic | |

| Schmid-Mohler et al 85 | 2014 | Switzerland | 1 H, Zurich | 12 | Transplanted | Interviews | Content | |

| Schober et al 206 | 2016 | USA | 14 states | 48 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Seah et al 50 | 2013 | Singapore | 3 H | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological | |

| Shahgholian et al 142 | 2015 | Iran | 1 H, Isfahan | 17 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Shaw et al 275 | 2015 | New Zealand | Diverse | 24 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Sheu et al 245 | 2012 | USA | Maryland | 27 | 23 | ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic |

| Shih et al 59 | 2011 | New Zealand | 1 C, North | 7 | ESKD | Interviews | Hermeneutical and thematic | |

| Shirazian et al 123 | 2016 | USA | 1 C, Northeast | 23 | CKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Sieverdes et al 174 | 2015 | USA | 1 C, South Carolina | 27 | Transplanted | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Smith et al 207 | 2010 | USA | 2 C | 19 | ESKD | Focus groups | Content | |

| Spiers et al 177 | 2015 | UK | 1 C, London | 4 | Transplanted | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological | |

| Spiers et al 171 | 2016 | UK | 2 online groups | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Stanfill et al 178 | 2012 | USA | 1 C, mid-South | 7 | Transplanted | Focus groups | Iterative | |

| Stewart et al 81 | 2012 | USA | 2 C, urban | 19 | ESKD | Interviews | Coding | |

| Tanyi et al 201 | 2006 | USA | Mid-West | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Tanyi et al 192 | 2008 | USA | 2 C, mid-West | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Tanyi et al 193 | 2008 | USA | Mid-West | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Tavares et al 216 | 2016 | Brazil | 1 H, Rio de Janeiro | 19 | ESKD | Interviews and groups | Content | |

| Taylor et al 111 | 2016 | Australia | 2 H, Sydney | 26 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Taylor et al 215 | 2015 | UK | 6 trusts | 15 | 11 | ESKD | Interviews | Constant comparison |

| Theofilou et al 122 | 2013 | Greece | 1 H, Athens | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Thomé et al 247 | 2011 | Brazil | 1H, Rio Grande do Sul | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Cultural | |

| Tielen et al 179 | 2011 | The Netherlands | 1 C | 26 | Transplanted | Interviews | Q methodology | |

| Tijerina et al 76 | 2006 | USA | 8 C, Texas | 26 | ESKD | Interviews | Coding | |

| Tong et al 63 | 2009 | Australia | 4 H, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne | 63 | CKD/ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic | |

| Tong et al 152 | 2013 | Italy | 4 C, Bari, Marsala, Nissoria, Taranto | 22 | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Tong et al 237 | 2015 | Australia | 1 C, Adelaide | 15 | CKD/ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Tonkin-Crine et al 127 | 2015 | UK | 9 C | 42 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Torchi et al 153 | 2014 | Brazil | 1 C, Rio de Janeiro | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Collective subject technique | |

| Tovazzi et al 117 | 2012 | Italy | North | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Tweed et al 109 | 2005 | UK | 1 C, Leicester | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Urstad et al 242 | 2012 | Norway | 1 C | 15 | Transplanted | Interviews | Hermeneutic | |

| Valsaraj et al 60 | 2014 | India | 1 H, South Karnataka | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Velez et al 100 | 2006 | Spain | 1 C | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Vestman et al 263 | 2014 | Sweden | 1 H | 9 | ESKD | Written narratives | Thematic | |

| Visser et al 276 | 2009 | The Netherlands | 1 C | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Wachterman et al 172 | 2015 | USA | 1 C | 16 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Walker et al 124 | 2012 | UK | 1 H | 9 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Walker et al 51 | 2016 | New Zealand | 3 C | 43 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Walker et al 61 | 2016 | New Zealand | 3 C | 43 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Walker et al 80 | 2017 | New Zealand | 3 C | 13 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Walton et al 258 | 2002 | USA | 1 H, rural, Northwest | 11 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Walton257 | 2007 | USA | 1 C | 21 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Weil253 | 2000 | USA | 2 C, rural, Northwest | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Wells254 | 2015 | USA | 3 C, 1 NP, Texas | 17 | 17 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Wells62 | 2015 | USA | 3 C, 1 NP, Texas | 15 | 21 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| White et al 139 | 2004 | USA | 1 C, Colorado | 6 | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic |

| Wiederhold et al 185 | 2012 | Germany | 1 C | 10 | Transplanted | Interviews | Content | |

| Wilkinson et al 75 | 2011 | UK | Luton, West London, Leicester | 48 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Wilkinson et al 233 | 2014 | UK | 4 C | 16 | 45 | Transplanted | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic |

| Wilkinson et al 74 | 2016 | UK | 4 C | 16 | 45 | ESKD | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic |

| Williams et al 101 | 2009 | Australia | 2 H | 20 | CKD | Interviews | Qualitative | |

| Williams et al 102 | 2008 | Australia | 2 H, Melbourne | 23 | CKD | Interviews and focus groups | Interpretative | |

| Williams et al 261 | 2009 | Australia | 1 H, Melbourne | 23 | CKD | Interviews | Qualitative | |

| Wilson et al 255 | 2015 | UK | 3 C | 15 | 15 | ESKD | Focus groups | Thematic |

| Winterbottom et al 230 | 2012 | UK | 1 C, Northern England | 20 | CKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Wu et al 66 | 2015 | Taiwan | 2 C, Central | 15 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Xi et al 110 | 2011 | Canada | 1 C, Ontario | 13 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Xi et al 158 | 2013 | Canada | 1 C, Ontario | 10 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Yeun et al 143 | 2016 | South Korea | 1 H, Seoul | 33 | ESKD | Interviews | Q methodology | |

| Yngman-Uhlin et al 135 | 2010 | Sweden | Southeast | 14 | ESKD | Interviews | Phenomenological | |

| Yngman-Uhlin et al 132 | 2016 | Sweden | 1 H, Southeast | 8 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Yodchai et al 249 | 2016 | Thailand | 2 H, Songkhla | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Qualitative | |

| Yodchai et al 199 | 2012 | Thailand | 1 C, South | 5 | ESKD | Interviews | Grounded theory | |

| Yu et al 112 | 2014 | Singapore | NKF | 32 | ESKD | Interviews | Thematic | |

| Yumang et al 144 | 2009 | Canada | 1 H, Quebec | 9 | ESKD | Interviews | Colaizzi’s method | |

| Ziegert et al 213 | 2001 | Sweden | 12 | ESKD | Interviews | Pragmatic approach | ||

| Ziegert et al 211 | 2006 | Sweden | Southwest | 13 | ESKD | Interviews | Content | |

| Ziegert et al 212 | 2009 | Sweden | Southwest | 20 | ESKD | Interviews | Content |

*Includes healthcare staff.

C, centre, unit or clinic; CKD, chronic kidney disease; D, dialysis; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GP, general practice; H, hospital; HD, haemodialysis; NA, not available; NKF, National Kidney Foundation (Singapore); NP, nephrology practice; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the development of the research question. To ensure wide dissemination of this systematic review, it is published in peer-reviewed open-access journal and presented in research meetings.

Results

Combined searches yielded 5407 citations and resulted in 260 studies from 30 countries included in the final analysis. A total of 5115 patients and 1071 carers were included. Countries most frequently represented in the studies were: the USA with 52 (20%), the UK with 46 (18%), Brazil with 28 (11%), Australia with 25 (10%), Canada with 20 (8%), Sweden with 19 (7%), New Zealand with 8 (3%) and Iran with 7 (3%) studies. Most studies (n=193, 74%) described the experiences of patients with ESKD, in dialysis or conservative treatment, 28 (11%) studies reported on transplanted patients, 17 (6%) studies referred to patients with CKD stages 1–4 and the remainder studies described experiences of patients with CKD in all stages. Table 2 shows characteristics of studies included in the review, box 1 shows illustrative quotations, table 3 shows summary of results and table 4 shows main challenges related to BoT.

Box 1. Illustrative quotations.

Structural inequalities

(Undocumented immigrant in US without access to scheduled haemodialysis) When you enter through the emergency department, you arrive in bad shape…you need to have a high potassium or they send you home even though you feel you are dying. Sometimes, you crawl out when they decide to not do dialysis. You eat a banana because it is high in potassium even though you may die and you go back and wait and hope that they will do dialysis so that you don’t feel like you are drowning and so that the anxiety goes away (American patient).52

My mother got some help from DIF (Mexican social assistance office), it was five haemodialysis sessions; when there was no session left, we went to a private centre, there is a foundation there and they helped us… they gave me eight sessions. After that, my mom went to DIF in Zapopan again and they sent us to DIF in Guadalajara. We got some help there (Mexican patient without coverage).47

Workload

Sometimes I have to sit and wait at least an hour and I have to call and say my ride is not here yet, which makes me late getting there, which makes me late getting on the machine, which makes me late getting off the machine. And then… coming to pick you up, if you’re not ready when they get there, they will leave you and you’ll have to sit and wait and wait and wait (American patient).86

It is always in the back of your mind that it (the transplant) will fail, at times. And I think if anything that makes you more inclined to comply with your treatment, comply with your medication because at the end of the day if, you know, if you do the utmost that you can and you take your medicine and you go to your follow up appointments, then there’s hopefully less chance of it failing in the long run (woman, 3 years+post-transplant).175

I suppose mine being genetic. It’s been very difficult to find what kind of diet you’re supposed to follow. You read one bit of information and it tells you this and you read another bit and it tells you don’t eat that, which the other one said you must eat. there’s no clear guideline on what it is you can or can’t eat (man, 38 years, CKD stage 3).94

It was a lot more work because of all the things that you had to learn… I don’t eat out anymore… It’s tough taking so many pills (patient with CKD).92

Capacity

Before she left (pause) when everything was happy and happy sort of thing, you know, I think it was—she was going to give a kidney to somebody else and somebody else was going to give a kidney to somebody and somebody was going to give a kidney to me—like a triangle… she was willing to do that. It didn’t happen, um (pause) ‘cos she left (UK patient).39

it’s a kind of tiredness that you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy… when you can’t read, you’re too tired to watch the telly, you’re too tired to do anything, because your brain is so tired like all of you… it feels like you’re kind of hollow inside… like it’s only a kind of shell that’s functioning.137

Well about five years ago, I went to the hospital because I wasn’t feeling good and they took my blood pressure and it was 200 over something…Then while they were trying to get my blood pressure down, they said something about my kidneys. And I didn’t know the connection between high blood pressure and kidneys (Evan, African-American male, 50, CKD stage 3).35

It wasn’t till about 2 years ago, until I fully understood and I’ve had the kidney disease from the age of 15, what exactly my (kidney) function was and I got a fright. No one had ever told me (man, 38 years, CKD stage 3).94

Control and decision-making

I have free rein of whatever days I want to take off. They don’t tell me when I have to dialyse or when I can’t dialyse. Everything is under my control. That’s what I like (talking on home dialysis, patient from Canada).158

If I’m going to feel this bad for the rest of my life, do I just want to end it now? (woman, 40s, CKD stage 4).63

Carers’ involvement

I just sit here like a robot. Nurses asked me to buy items that my mother needed. They never told me why she needed them. They ordered me to pay for dialysis, laboratory investigations and other things. I don’t like it when I do not know the reason behind my actions. I am sad to see myself as a fool being tossed around (caregiver from Nigeria).65

End of life

Then (the home care nurse) said ‘Well you haven’t got to go on. We’ll make it quite peaceful for you to pass on'. They can tell you, but it’s your body. It’s up to me to decide what I want to do (patient from the UK).205

I have heard (about) a lot of people that died on dialysis and had strokes on dialysis… Once I sit down there, I don’t know whether I’m gonna come out alive or dead (Berta, aged 45 years, blind amputee, dialysis patient for 18 months).76

I think about (death) everyday. I mean you can’t help it. I know that it is a terminal illness and it’s not going to get better and that there is only one way out (wife of a Canadian patient on peritoneal dialysis).286

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Table 3.

Summary of results

| Qualitative analysis | ||

| Primary category | Secondary category | Summary results |

| Structural disadvantage | Access to care | Socioeconomic status is central to experience of CKD.35 37–63 125

Treatment costs were major obstacle to care47–49 64 125 as was limited access to healthcare for the uninsured or underinsured.35 40 48 50 52 60 67 68 Transplants, dialysis and drug treatments were often beyond the reach of low-income patients.35 47–49 66 83–85 125 Uninsured or underinsured people experienced increased dependence on emergency care.35 47–49 52 66 Poorly funded or unfunded healthcare was often fragmented and of indeterminate duration.47 48 64 For non-native speakers, language was an important barrier for having a discussion with care providers.53 74–76 Patients were often poorly informed about disease progression and treatment options.38 50 57 58 63 64 125 127–129 188 205 219–222 |

| Housing | Homelessness, unsuitable housing, lack of utilities (electricity, clean running water) are critical to self-care and home dialysis.51 61 70 86 | |

| Employment status | Loss of employment may lead to uninsurance or underinsurance that limits or prevents access to treatment.35 39 45 52 60 69 72 87–91 | |

| Workload | Self-care | Complex medication regimens were managed through dispensing aids, associated activities, family support.40 46 71 86 92–103

When taking care of their vascular access, patients made efforts to protect the arm.108 111 Patients controlled their diets and fluid intake, and managed food cravings and thirst.63 112 Many modified social activities to minimise exposure to hot weather, temptation and social pressure.112 118–120 Women could face family conflicts if they followed prescribed diets.45 62 121–124 Restrictive diets were sometimes stigmatised as a sign of poverty.121 |

| Navigating healthcare structures | When pathways in system were not established, patients and carers had to identify institutions to obtain treatment and laboratory results.48 49 125 161

In settings with healthcare coverage, socioeconomically disadvantaged patients found it difficult to access financial support.51 Lack of continuity of care contributed to patients using services without sufficient expertise in CKD.49 101 The efficiency focus of medical system was perceived as a barrier to a personal connection.102 173 |

|

| Negotiating costs and fund-raising | Fund-raising was important for those who were uninsured or underinsured, sold goods or services, organised raffles or obtained loans.47–49 125

Patients contacted centres, other patients and organisations to ask for free treatment when they were uninsured or underinsured.47 49 52 125 217 218 |

|

| Travel and time management | Patients often travelled for long distances to dialysis centres, three times a week.15 47–49 53 76 86 126–133

Home dialysis patients had to pay transport to training, appointments and other check-ups.53 61 69–72 Patients arranged daily activities between sessions, adjusted activities to their fatigue and tried to schedule medical appointments all on one day.55 134–145 Parents arranged child care while they were in sessions or when they were tired.49 53 55 154 155 |

|

| Home dialysis | Training was required with extended periods off work.61 70 156–158

Homes needed physical adaptation, carers invested efforts in maintaining cleanliness and hygiene.152 158–162 Specific tasks were managing treatment at set times, recording blood pressure and body weight, titrating medications, adopting aseptic techniques.156 157 163 |

|

| Pretransplant adaptation | Patients adjusted to being on transplant waiting-list, prepared for transplant from a deceased donor at any time.43 115 133 164–170

Specific adjustment tasks included: hospital visits, tests and organising payment for treatment.132 133 164 165 170–173 Some people needed to negotiate donation of a kidney by living relatives or others.39 47 164 174 |

|

| Post-transplant adjustment | Transplanted patients managed complex medication regimens, balanced against the need to re-enter the labour market to pay off loans.84 85 175–180

Post-transplant, patients needed to manage relationships, finances and family responsibilities in context of prognostic uncertainty.83 85 175–177 181–186 |

|

| Capacity | Physical and mental capacity | Daily activities were limited by symptoms associated with dialysis (pain, fatigue, anxiety and depression).37 44 55 63 90 96 138 140 154 187–199

Symptoms were sometimes overlooked by healthcare professionals.58 94 101 202–204 When in poor health, patients relied on wider networks for food preparation, transportation, shopping, ordering supplies, symptom management and training.37 118 161 205–208 Carers were involved in the treatment, accompanying patients to dialysis and responding to psychosocial needs.45 69 97 129 141 143 161 210–215 |

| Managing information | Information on disease and treatment was often insufficient or difficult to comprehend, particularly during early stages.61 77 92 109 121 130 131 223–227

Short clinic visits, jargon and anxiety were barriers to accessing information.61 102 223 231–234 For organ donation and transplantation, patients relied on information from other patients, healthcare professionals, social workers, financial representatives, meetings and the internet.117 174 235–238 Information about the effects and side effects of immunosuppression was important but hard to come by.178 184 185 239–242 Stress and urgency affected how people with CKD processed information provided by healthcare professionals.240 242–245 |

|

| Social support | Support from friends, family, neighbours, healthcare professionals and other patients was essential.39 44 60 62 215 247 252–256

Lack of social support was a frequently reported problem.44 60 247 259 Patients ought to maintain a sense of normalcy, integrating dialysis community into their network.42 139 210 260 Younger patients sometimes considered home dialysis as an opportunity for employment and contact with social networks.61 152 |

|

| Experienced control | Personal control and decision-making | When clinicians failed to discuss care, eligibility for transplant and potential donors, patients felt disempowered.39 55 57 58 77 78 169 282

When relatives offered to donate a kidney, many patients were reluctant to accept because of concerns on future health of donor; other patients had reservations about kidneys from deceased donors because of the donor’s age, medical history.172 181 235 Once transplanted, main clinical objective was preserving the graft.49 63 89 96 167 283–285 |

| Carers’ involvement | Carers needed more information on dialysis techniques to feel confident, stressed the importance of 24 hours telephone support, wanted to be involved in decision-making as dialysis would also affect them.55 70 111 156–158 223 279 286

When carers perceived patient was in pain with no response to treatment, they sometimes yearned for the patient’s freedom of this condition through a peaceful death.134 141 161 |

|

| End-of-life decisions | Patients and carers emphasised self-determination, autonomy and dignity.134 136 205 251 294

End-of-life decisions were influenced by ideas about personal fulfilment, nature taking its course, fears of dependence or of dialysis accelerating death.128 293 Decisions often passed to trusted carers or professionals.290–292 Acceptance of decisions was influenced by treatment modality, patient age and ineffectiveness of haemodialysis.64 128 134 161 Families emphasised importance of respecting patients’ wishes.202 233 292 |

|

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Table 4.

Main challenges related to burden of treatment

| Challenge | Group of patient mostly affected | Type of country mostly affected | Severity |

| Limited access to healthcare for the uninsured or underinsured. | CKD, ESKD | LMIC | +++ |

| Dialysis, transplant surgery, immunosuppressive drugs were often beyond the reach of low-income patients. | ESKD | LMIC | +++ |

| Healthcare was often fragmented and of indeterminate duration for the uninsured or underinsured. | CKD, ESKD | LMIC | +++ |

| In settings with healthcare coverage, socially disadvantaged patients found it difficult to access financial support. | CKD, ESKD | HIC | ++ |

| Fund-raising was important for those who were uninsured or underinsured. | ESKD | LMIC | +++ |

| For non-native speakers, language was an important barrier for having a discussion with care providers. | CKD, ESKD | LMIC, HIC | ++ |

| Patients were often poorly informed about disease progression and treatment options. | CKD, ESKD | LMIC, HIC | ++ |

| Patients and carers had to identify institutions to obtain diagnosis, laboratory results and treatment. | CKD, ESKD | LMIC | ++ |

| Homelessness, unsuitable housing, lack of utilities, critical to self-care and home dialysis. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Loss of employment may lead to uninsurance or underinsurance limiting or preventing access to treatment. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | +++ |

| Complex medication regimens were managed through dispensing aids, associated activities, family support. | CKD, ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| When taking care of their vascular access, patients made efforts to protect the arm. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| Patients controlled diets and fluid intake, modified social activities to minimise exposure and pressure. | CKD, ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Patients often travelled for long distances to dialysis centres, three times a week. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Home dialysis patients had to pay transport to training, appointments and other check-ups. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Patients arranged daily activities between sessions. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| For home dialysis, training was required with extended periods off work. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| For home dialysis, homes needed physical adaptation. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| For home dialysis, tasks were managing treatment, monitoring, titrating medications, adopting aseptic techniques. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Pretransplantation, specific adjustment tasks included: hospital visits, tests and organising payment for treatment. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | |

| Some people needed to negotiate donation of a kidney by living relatives or others. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Transplanted patients managed complex medication regimens. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | + |

| Transplanted patients needed to manage relationships, finances and family responsibilities. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Symptoms associated with dialysis limited daily activities, sometimes overlooked by healthcare professionals. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| When in poor health, wider networks were necessary for daily activities, transportation, symptom management. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Information on disease and treatment was often insufficient or difficult to comprehend. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Information about immunosuppression was hard to obtain. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Lack of social support was a frequently reported problem. | ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Many clinicians failed to discuss care, eligibility for transplant and potential donors. | CKD, ESKD | HIC, LMIC | ++ |

| Carers needed more information on dialysis techniques to feel confident. | ESKD | HIC | + |

| Patients and carers emphasised self-determination, autonomy and dignity when nearing end of life. | ESKD | HIC | ++ |

Severity: + mild, ++ moderate, +++ very severe.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country.

Structural inequalities

Access to care

Poverty and other socioeconomic disadvantages such as unemployment or poor housing conditions were defining factors for lack of treatment or interrupted care.37–52 Living as a person with CKD and ESKD always implied some degree of financial burden, from having to pay for the whole dialysis treatment or transplantation surgery to out-of-pocket payments of incidentals, even in countries with universal coverage.35 47–49 51 53–63 Poorly funded or unfunded healthcare resulted in fragmented treatment across healthcare systems.47 48 64 Although patients who had difficulties affording treatment were naturally more concerned with accessing healthcare than in improving services, they recognised fragmentation and lack of integration as important problems.40 45 48–51 Where government or private insurance coverage of ESKD treatment was limited, for example, Mexico or India, patients paid for some or all the following: vascular access, hospitalisation, medical visits, haemodialysis sessions, medication, tests, prescribed food, transport and meals.45 47–50 60 65 In such settings, patients received dialysis treatment only if they could afford it or when they had access to free sessions.45 47–50 60 65 Medication was sometimes counterfeit, obtained on the black market, as legitimate medication was beyond patients’ reach.49 For the uninsured, dependence on emergency care added uncertainty and risk, whatever their treatment modality, as in the case of many undocumented and uninsured immigrants in the USA.35 47–49 52 66 In countries with poor healthcare infrastructure, patients reported shortage of public specialised hospitals, long delays to undergo examinations, limited number of haemodialysis machines available, lack of ward space or poor bed conditions in hospitals, for example, poor hygiene, worn-out mattresses, shortage of linen; to avoid delays, patients sometimes had tests performed by private providers.40 50 60 67 68

When home dialysis was available, patients had to pay for transport to training, appointments and other check-ups; moreover, some equipment, supplies, increased utility bills and home modifications represented unexpected expenses.51 53 61 69–73 In countries with coverage of RRT, for patients whose first language was different from that where treatment was received, as in the case of migrants, communication was a barrier for discussions with healthcare professionals; family members and neighbours acted as translators at appointments.53 74–76 Where language was shared, communications between clinicians and patients of different ethnic origins—for example, Australian Aborigines and New Zealand Maoris—was often itself a source of conflict and disadvantage, because of prejudice.53 57–59 77–82

In some countries, the transplantation procedure could be particularly expensive, even at public hospitals.35 47–49 66 83 Moreover, patients sometimes found that the expensive immunosuppressants necessary after the transplant were not covered by their insurance; other patients who obtained information about the high costs of immunosuppressants and realising that they could not afford them, were forced to continue with dialysis until it failed.49 83–85 In Mexico, structural constraints resulted in transplanted patients being sent back to small peripheral clinics with no transplantation expertise, increasing the risk of iatrogenic or poorly managed complications.83

Housing conditions

Unsuitable housing was a barrier to home dialysis if it could not accommodate equipment, and was impossible without an adequate electricity supply.51 61 In rented accommodation, landlords might not approve of necessary modifications. Home dialysis was not a treatment option for those with no fixed abode.51 61 70 86

Employment status

Patients who were physically able to continue working often had informal or temporary jobs, with diminished income; others were forced into unemployment, leading to new financial problems.39 45 52 60 69 72 87–91 Unemployed patients in the USA were covered by government or state schemes; however, this coverage either diminished or ceased if they found work with a new insurance.35 52

Patient workload

Self-care

People with CKD and ESKD had complex medication regimens managed through dispensing aids, daily activities associated with medication taking such as meals, family support or a combination of these.40 46 71 86 92–106 Anticipating dialysis, patients underwent vascular access, a way to reach the blood for haemodialysis, undergoing minor surgery and care needed to be taken to prevent infections or clotting.66 107–110 To care for their vascular access, patients kept the access area clean, changed bandages, restricted themselves from lifting heavy objects and were alert for pain or hardness in the area.108 111

Patients controlled their diets and fluid intake between dialysis sessions, and managed food cravings and thirst with strategies such as thinking of the potential detrimental consequences of drinking water, avoiding thoughts and behaviours that could trigger thirst and modifying social activities to minimise exposure to hot weather, social pressure and temptation to intake certain foods or fluids.46 63 112–120 Women also faced potential family conflicts if they followed prescribed diets.45 62 121–124 In certain cultures, including immigrants who preserved their customs in other countries, the perceived association of a rich diet and wealth acted as a barrier to adherence to a restrictive diet, essential to self-care, as patients feared being stigmatised as poor.62 121 125

Travel and time management

People with ESKD travelled to haemodialysis centres three times a week, received treatment for several hours and then transported themselves home again; very often, transportation represented a problem for patients because of pick-up delays, long distances or high costs.15 47–49 53 76 86 126–133 Patients receiving dialysis arranged their daily activities between treatment sessions, adjusted the timing and intensity of their activities to their fatigue and tried to schedule medical appointments all on one day to avoid further interactions with the healthcare system.55 134–145 The treatment was seen by most patients as an emotional and time imposition that caused boredom and frustration.63 146–152 Time was often spent waiting for visits, prescriptions and tests.55 134–145 153 Parents also arranged child care while they were in sessions, or had to travel for treatment.49 53 55 154 155

Home dialysis

For patients receiving home dialysis, training was required which necessitated extended periods of leave from work.61 70 156–158 They and their families had to adapt their home to accommodate equipment and materials, and spent more time cleaning in case healthcare workers assessed their housing conditions.152 158–162 Tasks associated included managing treatment at set times each day, recording blood pressure and body weight, titrating medications and adopting aseptic techniques, as well as adhering to diet and fluid restrictions.156 157 163 In the case of developing peritonitis, workload increased as antibiotics had to be reconstituted and injected.156 157

Pretransplantation adaptation

People with ESKD adjusted to being on the transplant waiting list and prepared for the possibility of receiving a kidney from a deceased donor at any time.43 115 133 164–170 The tasks included hospital visits, several investigations and tests, saving money for the operation and maintaining robust health; many potential recipients felt overwhelmed by all that was necessary.132 133 164 165 170–173 Talking to others about their requirement for a kidney transplant involved making the request itself to potential living donors, educating people about CKD, treatment options and donation.39 47 164 174

Post-transplantation adjustment

After transplantation, patients’ workload included financial and occupational changes resulting from a new type of treatment and status, managing complex medication regimens and managing social relations.84 85 175–180 These tasks had to be balanced against the work of safeguarding access to healthcare, organising their disability insurance, interacting with healthcare providers, managing symptoms, monitoring medication side effects and managing self-care in relation to diet, fluid and physical activity.84 85 175–180 Although transplantation was seen as a route back to normality, it was laden with ambiguous feelings towards the donor, unanticipated challenges in forming or maintaining relationships, financial worries, the responsibility of supporting their family, disappointments when side effects were noticed and a prevailing prognostic uncertainty.83 85 175–177 181–186

Navigating healthcare structures

Very often, patients had to identify and call on the appropriate institutions to obtain a diagnosis, laboratory exams, treatment or coverage; contacting several public and private healthcare providers, social insurance offices, charity organisations and non-governmental organisations.48 49 125 161 In settings with coverage of RRT, socioeconomically disadvantaged patients could also find it difficult to access financial support and navigate the social support system, which resulted in not receiving the assistance to which they were entitled.51 Lack of continuity of care contributed to patients using services without sufficient expertise in CKD or ESKD, such as emergency departments or peripheral health centres.49 101 The efficiency focus of the medical system was perceived by patients and professionals as a barrier to a personal connection; moreover, patients also recognised professionals’ dismissive attitudes towards patients’ experiential knowledge.102 173

Negotiating costs and fund-raising

Those patients and carers in countries with limited health coverage needed to perform additional work; poor families sold goods, products or services, organised raffles to collect money or obtained loans.47–49 125 They also contacted treatment centres, other patients, hospitals and non-government organisations to ask for free dialysis sessions or medication. For this reason, disadvantaged people were advised by healthcare staff on how to seek help in charities and advocacy organisations.47 In more affluent settings, patients also struggled to negotiate coverage of extra expenses, such as those related to home dialysis or conservative management.51 161

Capacity

Physical and mental capacity

The ability of people with ESKD to carry out daily activities, including their paid job, was limited by symptoms associated with the disease and dialysis treatment, such as pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression and sexual problems,37 44 55 63 90 96 138 140 154 187–201 sometimes overlooked by healthcare professionals.58 94 101 202–204 When in poor physical health, patients relied on wider family networks and neighbours to help with activities related to BoT such as scheduling and attending medical appointments, arranging transportation to those appointments, ordering and arranging medical supplies and training; also, other daily tasks such as food preparation, or shopping.37 118 161 205–209 Carers were involved in the dialysis procedure, accompanying patients to dialysis and responding to psychosocial needs.45 69 97 129 141 143 161 210–216 Patients’ capacity to carry out the activities related to healthcare were affected by insufficient financial resources and the fear of catastrophic consequences, such as death because of lack of dialysis treatment or immunosuppressive medication in the case of transplanted patients.47 49 52 217 218

Managing information

Obtaining information on the disease and treatment was a significant burden for patients and carers. Patients reported that their information on the disease and treatment options was often insufficient or difficult to comprehend, particularly during the early stages of their trajectory, independent of income or coverage level.38 50 57 58 61 63 64 77 92 109 121 125 127–131 188 205 219–230 Patients may not have asked for clarification for fear of not understanding or because they did not even know what to ask; the desire for more patient-centred care were widely expressed. Short clinic visits, unknown technical jargon and high levels of anxiety were barriers to accessing information.61 102 223 231–234 Other patients could sometimes supply information about dialysis options, travelling, hygiene regimens, dietary restrictions, benefit advice, timing of treatment and pain management.117 174 235–238 For organ donation and transplantation, people usually received information through discussions with other patients, providers, social workers, financial representatives, the internet and, in affluent populations, informative meetings.117 174 235–238 In relation to transplantation, patients reported they needed practical information about the unexpected side effects of immunosuppressive medication; most frequently mentioned were higher risk of cancer, infections, weight gain and fragile skin.178 184 185 239–242 Other information needs for transplanted patients included coping with emotions related to the transplant, what to do when a suitable organ became available, alternatives to transplantation and how the waiting list worked.240 242–245 Family members were afraid to bother the healthcare team,246 and perceiving little power in comparison to healthcare professionals, downplayed their knowledge in front of them.210 Patients and carers were responsible for obtaining and carrying their medical files and test results to appointments when the healthcare administrative systems were not integrated.49 125 Some had anticipated that transplantation would offer dramatic health improvement but were disappointed when they experienced side effects, particularly cancer.44 63 101 106 122 167 190 193 199 206 214 247–251

Social support

Most people highlighted the support from family, neighbours, friends, staff, other patients and church communities; friends, staff and spiritual groups were particularly important for those living alone.39 44 60 62 215 247 249 252–258 A lack of social support was also frequently reported.44 60 247 259 In a UK study, patients' socioeconomic disadvantage adversely affected the availability of social support, and it was suggested that personal relationships sometimes broke down when potential donors declined to donate.39 Attending dialysis was sometimes seen as a social outlet, where they could make friends with staff and patients. Younger participants often considered the schedule flexibility of home dialysis as an opportunity for maintaining their employment and contact with their family and established social networks.61 152 To demonstrate resilience, some patients tried to maintain a sense of normalcy, integrating the dialysis community into their social network.42 139 210 260

Experienced control

Personal control

Feelings of personal control were achieved through learning how to manage CKD and ESKD, finding a balance between illness and normalcy, or even denying the seriousness of their condition.218 260 261 The experience of feelings of personal control led to increased self-confidence and well-being.15 189 251 Strategies for maintaining control included requesting tests, withholding information from clinicians, monitoring and modifying their treatments and checking the activities of dialysis nurses assisting them.139 246 251 262–265 People with ESKD experimented with their therapy to determine if the prescriptions were really necessary, they also shortened dialysis hours to reduce worsening symptoms, to meet work commitments, or to participate in an unexpected social situation.54 55 Lengthening treatment hours could facilitate higher than usual fluid removal or managing symptoms.54 55 Some patients entrusted decisions entirely to the care team, and this promoted feelings of security.61 70 102 107 266 267 The main barrier to personal control was lack of information about treatments, test results and the course of their illness and that they could not choose when and where to travel.15 43 61 63 197 239 268 However, even when patients knew they were not in control, they felt unsafe if the treatment went differently from what was expected.269 Patients recognised prognostic uncertainty, and their own fear of incompetence as an obstacle to choosing the appropriate dialysis modality.54 72 92 132 133 150 161 223 251 268 270–274 For many patients, home dialysis restored a sense of control and freedom to manage their schedule, especially if it was nocturnal.51 70 158 220 263 275 Dependence on emergency care or on fund-raising tasks to cover life-saving treatment represented a severe case of lack of experienced control.35 47–49 52 66

Control and decision-making

Control translated into participation in decision-making, which was affected by the healthcare staff’s attitude towards the patients’ adherence to treatment.236 Lack of choice in decision-making about dialysis modality was very common; when possible, modality was negotiated and agreed after discussions with clinicians and family members, reading educational material or attending informational meetings.202 248 270 273 274 276–278 Home dialysis patients appreciated training to build confidence and skills to use the machine.54 70 111 270 279 280 Patients in dialysis aspired to improve their situation by receiving a transplant, motivating them to adhere to treatment; other motivations included family, especially their children, work and beliefs.55 58 281 People with ESKD whose clinicians failed to discuss care, eligibility and ineligibility for transplant, and potential donors with them felt disempowered.39 55 57 58 77 78 169 282 When relatives offered to donate a kidney, many patients felt reluctant to accept this because of their concerns about the future health of the donor; other patients had reservations about accepting kidneys from deceased donors because of the donor’s age and medical history.172 181 235 Once transplanted, the main clinical objective was preserving the graft. However, the disease and its treatment continued to be a significant burden on patients’ social capital and financial capacity, with unexpected side effects.49 63 89 96 167 283–285

Carers involvement

Relatives wanted to be involved in discussions on dialysis modality as dialysis would take up a large part of their lives.55 70 111 156–158 223 279 286 Carers of patients on home dialysis needed to know more about the dialysis techniques to feel confident about self-managing the treatment, they stressed the importance of 24 hours telephone access for advice.61 69 Family members were afraid to bother the healthcare team,246 and perceiving little power in comparison to healthcare professionals, used strategies to downplay their knowledge of the disease or the treatment in front of them.210 287 To cope with caring, carers sought support in psychiatric help or religion when available, or support in religion.141 247 Patients who decided to stop dialysis did not usually ask for their carers’ opinion; when physicians thought the patient was too ill to decide, carers were consulted and felt death could be liberating if the patient was in pain and with no response to treatment.134 141 161

End-of-life decisions

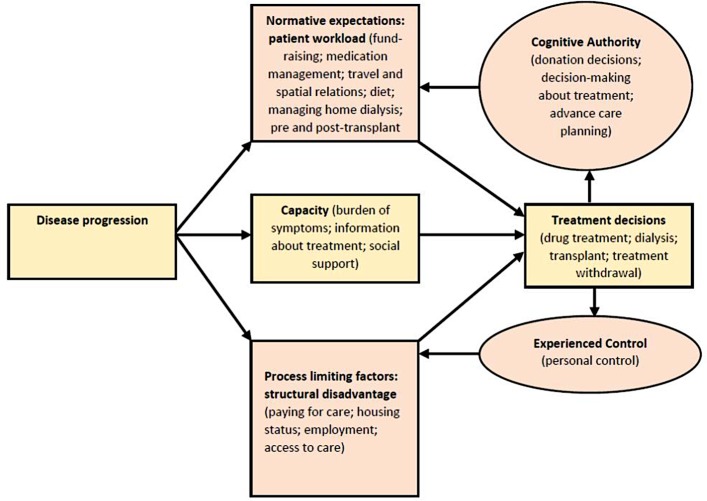

Some patients felt that advance care planning (ACP) was hard and unnecessary as they trusted their families to make decisions; others were less concerned, trusted their healthcare team and felt empowered.236 288 289 Family members felt ACP was necessary as a means to protect patients.290–292 At the end of life, maintaining control was a struggle with respect to autonomy and dignity.134 136 205 251 Patients based their dialysis withdrawal or non-acceptance decision on having lived a full life, on nature taking its course, on their fear of being a burden for their families, their bodies being invaded and dialysis accelerating death.128 293 For some, the decision to withdraw from dialysis meant asserting their self-determination.251 294 Carers’ acceptance of patients’ decision was influenced by the perception of conservative management as a non-invasive treatment, the advanced age of the patient and the lack of benefit received from haemodialysis.64 128 134 161 Although family members were often uncomfortable about making end-of-life decisions, they tended to recognise it was important to respect the patient’s wishes.202 233 292 Figure 2 shows thematic schema of experienced control and cognitive authority in CKD.

Figure 2.

Thematic schema of experienced control and cognitive authority in chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the work and capacity of patients and carers are highly unstable situational factors that make up the BoT. Capacity is particularly diminished by socioeconomic factors, which ultimately exacerbates the work of patients and their carers; this may occur even in regions with universal health coverage. Particularly in LMICs, patients with ESKD are often underinsured or not at all, which makes it almost impossible for them to attain life-saving treatments. Patients with ESKD can be caught in a vicious cycle, whereby they lose their job and health insurance because of ill health or because they need time off from work to attend dialysis, leading to exacerbations in disease, lack of financial access to treatment and difficulty obtaining a job because of poor health. Patients often fear catastrophic consequences due to a lack of financial capacity, and make strenuous efforts to prevent them. Thematic syntheses with robust methods have covered different aspects of being a patient with CKD.295–308 Here, we focused on three elements of BoT, namely workload, capacity and experienced control, to develop an understanding of the BoT of CKD, focusing on ESKD and including the experiences of patients in contexts of structural inequalities.

Worldwide, many individuals with CKD and especially with ESKD receive no treatment or receive only fragmented care.8 35 309–314 Millions of preventable deaths occur because of lack of access to RRT.9 Moreover, in some LMICs with universal health coverage, resources may be limited because of geography or poor infrastructure; in such cases, the use of free health providers can create delays that compromise the treatment itself, resulting in patients struggling to pay for private providers. When this occurs, healthcare becomes fragmented and uncoordinated. Even in some modern welfare states, health inequalities persist, particularly affecting minorities, those who are unemployed or undocumented.315 One example is the use of emergency haemodialysis by undocumented and uninsured immigrants with ESKD.52 Several studies have highlighted the imperative necessity to address this disturbing reality.316–323