Abstract

Indigenous ancestral teachings commonly present individual and community health as dependent upon relationships between human and nonhuman worlds. But how do persons conversant with ancestral teachings effectively convey such perspectives in contemporary contexts, and to what extent does the general tribal citizenry share them? Can media technology provide knowledge-keepers with opportunities to communicate their perspectives to larger audiences? What are the implications for tribal citizens’ knowledge and views about tribal land use policies?

Using a PhotoVoice approach, we collaborated with a formally-constituted body of Cherokee elders who supply cultural guidance to the Cherokee Nation government in Oklahoma. We compiled photographs taken by the elders and conducted interviews with them centered on the project themes of land and health. We then developed a still-image documentary highlighting these themes and surveyed 84 Cherokee citizens before and after they viewed it. Results from the pre-survey revealed areas where citizens’ perspectives on tribal policy did not converge with the elders’ perspectives; however, the post-survey showed statistically significant changes. We conclude that PhotoVoice is an effective method to communicate elders’ perspectives, and that tribal citizens’ values about tribal land use may change as they encounter these perspectives in such novel formats.

Introduction and Purpose

Protecting natural landscapes helps maintain human health (Frumkin 2001; Frumkin and Louv 2007). Although clean air and water indisputably contribute to good health, researchers have also documented how land conservation aids humans in building relationships with non-human nature (Hansen-Ketchum 2015). Perspectives linking individual to environmental health share common ground with ancestral values widespread among Indigenous peoples (Garrett 1999; Arquette et al. 2002; Johnston 2002; Parlee et al. 2005; Altman and Belt 2009; Graham and Stamler 2010). Some tribes have asserted concepts of public health that include relationships with the natural world (see Arquette et al. 2002; Kahn-John and Koithan 2015; Donatuto et al. 2016). Others have established conservation areas and parks, similarly promoting visions of health wherein community well-being is embedded in the well-being of the surrounding natural world (Wood and Welcker 2008; Middleton 2011; Carroll 2014a).

For many Indigenous communities, however, the practical realities of communicating and implementing ancestral perspectives are complex. Urbanization, population dispersion, and changes in family structure have hindered forms of cultural knowledge transfer that depend on person-to-person relationships, kinship bonds, and experiential education. These hindrances can frustrate the efforts of knowledge keepers—as persons conversant with ancestral knowledge—to communicate cultural teachings to the larger tribal citizenry or to express how such knowledge might inform tribal land use decisions. Further, as sovereign nations, American Indians confront challenges in implementing policies that balance environmental and economic concerns.4 In the Cherokee Nation, constraints on personnel and funding, alongside the hegemony of profit-driven land management programs inherited by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, inhibit the development of more culturally-informed land use practices, such as wild plant conservation (Carroll 2014b).

These issues raise questions. What perspectives on environmental health do tribal knowledge-keepers seek to communicate, and how do they apply such perspectives to understand their tribes’ decisions about contemporary land use and conservation? To what extent does the general tribal citizenry share similar knowledge and values? Can media technologies augment ancestral knowledge and values in tribal audiences and influence perspectives on tribal land use policies?

We pursued these questions in partnership with the Cherokee Nation in northeastern Oklahoma, United States. Guided by PhotoVoice methodology (Wang and Burris 1997), we collected and analyzed qualitative and photographic data from the tribe’s formally constituted body of knowledge-keepers—the Cherokee Nation Medicine Keepers—inviting them to discuss their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about land use and health. Drawing on the resulting data, we developed a still-image documentary communicating these perspectives. We created a survey to assess prevalence of similar perspectives in the larger tribal citizenry, both before and after documentary viewing. The survey also measured citizens’ willingness to support tribal land conservation policies given specific tradeoffs.

Setting

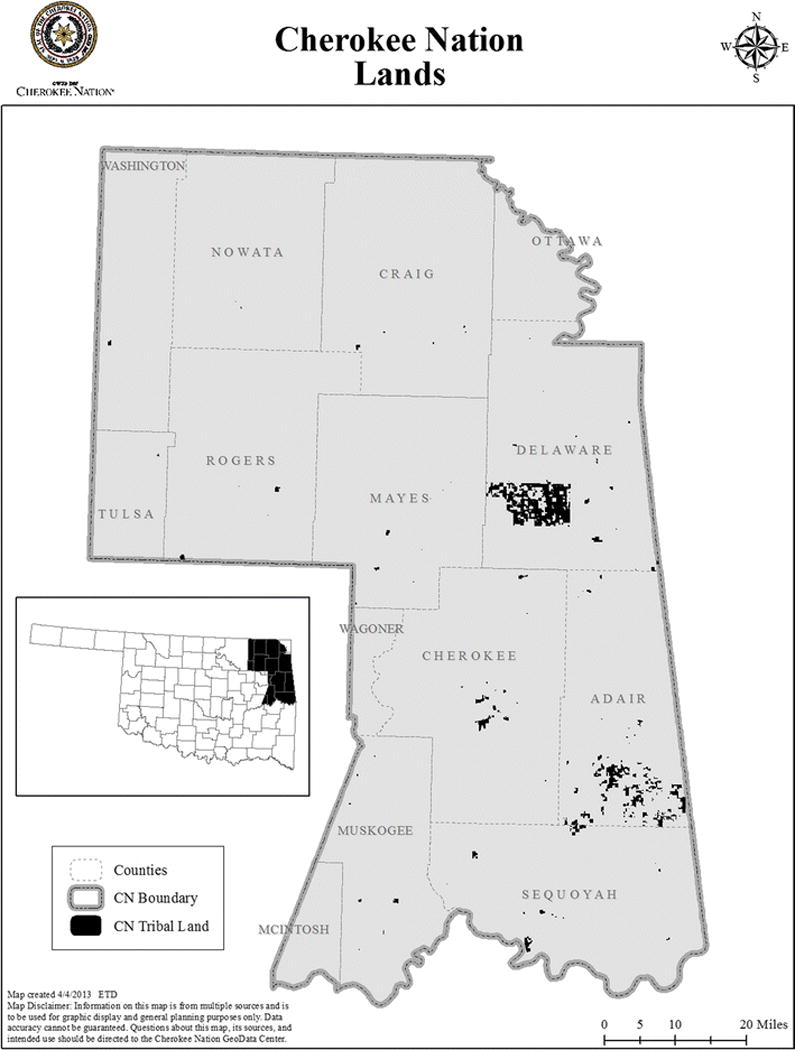

With a population of approximately 317,000 citizens, the Cherokee Nation is the most populous federally recognized tribe in the United States. The original Cherokee homelands comprised much of the present-day southeastern United States; however, due to the forced relocation beginning in 1838, the Cherokee Nation’s current land base is located in northeastern Oklahoma. Of the 4.42 million acres that Cherokees received in the “Indian Territory” (before Oklahoma statehood in 1907) in exchange for their land in the southeast, only about 100,000 acres currently remain under Cherokee control—primarily as tribal trust lands. Roughly 126,000 of the total citizenry lives within the fourteen-county Cherokee Nation Tribal Jurisdictional Service Area (Figure 1). The remaining citizenry resides throughout the United States, with major concentrations elsewhere in Oklahoma and in neighboring states (www.cherokee.org).

Figure 1.

Map of Cherokee Nation Tribal Jurisdictional Service Area and current tribal trust lands.

Research Partners

The Cherokee Nation Medicine Keepers consist of 11 elders (5 women; 6 men) whose mission is to perpetuate Cherokee knowledge of wild plants and to preserve the health of Cherokee lands for the benefit of present and future generations. The group serves as an advisory board for the Cherokee Nation’s ethnobotanical projects, which include an heirloom garden and seed bank program, and a culturally-significant native plant area at the tribal headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. A three-person editorial board consisting of group-selected members of the Medicine Keepers was established by Executive Order in 2013 and manages all Cherokee ethnobiological education materials. While the Medicine Keepers do not assert that their perspectives reflect the views of all Cherokee elders, their formal recognition as cultural advisors to the tribal government urges careful attention.

Methods

PhotoVoice

Rooted in community-based participatory research methodology, PhotoVoice promotes critical dialogue and new knowledge about community-defined issues through the use of photography. The method began as a participatory health promotion strategy and is explicitly designed to reach policymakers (Wang and Burris 1997; Wang et al. 1998). As a method, PhotoVoice offers an ideal way of visually capturing the literal point of view of a community.

In May 2015, we convened a “kickoff” meeting and workshop in Tahlequah, Oklahoma with the Cherokee Nation Medicine Keepers to review the themes and goals of the PhotoVoice project. During this meeting, the group identified the thematic concepts of land and health that would guide the project, and decided that the goal of the project would be to influence current tribal land use policy and promote conservation of tribal lands and resources. The Project Director (Carroll) then distributed a digital camera to each Medicine Keeper and gave a brief presentation on camera operation and some basics of photography, including composition and style. To test the cameras and provide a controlled practice session, the group walked to the nearby Cherokee Nation native plant area. Each participant took at least 5 photographs reflecting the previous training. The group reconvened after thirty minutes and Carroll uploaded and projected their photos for review. The group discussed them in relation to the PhotoVoice method and project goals.

We scheduled the next meeting four weeks away, during which time the Medicine Keepers each documented places, plants, and animals in the natural world that were special to them and that they thought conveyed specific teachings on Cherokee environmental ethics. In June 2015, Carroll scheduled in-person, audio-recorded interviews with each elder. Drawing on the “responsive interviewing” model (Rubin and Rubin 2012), he invited each elder to select 10 photos and to describe the featured location, plant, or animal, why they chose it, and how the photograph addressed the project theme and goals (Box 1). After the individual interviews, Carroll assembled each elder’s selected photos into a single presentation. The Medicine Keepers reconvened at their scheduled meeting, and at this audiotaped focus group interview, they agreed on the photos that best represented their collective voice on the project themes. They chose a name for the project video—“Cherokee Voices for the Land”—and recommended music for the video score.

Box 1. PhotoVoice individual interview question set.

Carroll asked initial open-ended questions regarding each photo, such as “Can you please tell me about this photo?” As needed, he posed additional probing questions for elucidation of additional meaning and context about each photograph (e.g., “What do you think about when you look at this image?”). Once each photo had been discussed, Carroll then asked broader questions about land, health, and conservation, such as, “In your opinion, what is a healthy landscape? What is a healthy community? How might they be related? What do you think would be lost if these places/plants/animals weren’t available to Cherokee people anymore? How would you propose to protect these things? Do you have any thoughts about the condition of lands in the Cherokee Nation today?”

During the two months following the individual and focus group interviews, Carroll inductively analyzed transcripts from the individual and focus group interviews using open coding (Charmaz and Belgrave 2012) to allow concepts to emerge that coincided with the project themes of land and health. He then used selective coding to develop categories for common themes found across the individual interviews (Table 1). Drawing on this analysis, he curated a 30-minute still-image documentary featuring the elders’ photographs and using selections of their audiotaped interviews as voiceovers. Carroll also developed a survey to assess the extent to which ordinary tribal citizens share elements of the elders’ perspectives and their willingness to apply them to specific actions. In August 2015, he presented the draft survey questionnaire and draft video to the Medicine Keepers and incorporated their comments and feedback into final versions that were unanimously approved by the group.5

Table 1.

Main themes from Medicine Keeper interviews

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Stewardship Ethic | “If we don’t use it, it will go away,” or “If we don’t use it, the Creator will take it away.” (use + stewardship ethic = healthy resource) |

| Tribal Land Management | Cattle grazing on tribal lands is ecologically detrimental due to land clearing and poor management. |

| Resource Access | Fencing land for cattle grazing decreases Cherokee access to wild plants. |

| Health and Subsistence | Cherokees have poorer health now compared to when people lived off the land. |

| Environmental Change | Conditions are different now due to forest clearing, fences, and contaminants. |

Survey Sample

We recruited 84 Cherokee citizens aged 18 and above during the 2015 Cherokee National Holiday, a large annual tribal event held in northeastern Oklahoma. We set up a projector and screen in a reserved room for 1.5 days, and advertised showings of the PhotoVoice documentary hourly. We advertised the screenings in the official event agenda to maximize awareness and participation, and we also recruited participants in the neighboring tribal gift shop. Eligible participants completed hard-copy consent forms and received a gift card (U.S. $10) for their participation.

Anonymous surveys, distinguished only by an identification number assigned to wireless electronic remotes, assessed participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding land conservation and health; the extent to which tribal policies should reflect traditional Cherokee values toward these concepts; and acceptable tradeoffs in service of these values. We projected the survey questions using Microsoft PowerPoint®. We used TurningPoint® polling software, asking participants to select the letter on their wireless remotes that corresponded to their answer. A wireless bay station automatically recorded and stored the information.

The pre-survey began with demographic questions to determine participants’ age, gender, tribal enrollment status, employment status, general health, and area of residence. We then asked participants a series of questions concerning environmental perspectives, values, and ethics thematized in the elders’ PhotoVoice interviews. Questions asked participants to report attitudes toward land conservation and health on a Likert Scale ranging from 1 (low) to 4 (high). Example survey questions are “How strongly do you feel land conservation should be a tribal priority?” and “How much do you associate the health of your community with the health of the local environment?” Other questions inquired about the degree to which participants were willing to pursue conservation in light of various tradeoffs. For example, “How willing would you be to conserve tribal lands if it meant reducing funding for Cherokee Nation education programs by 10%?”

Participants next viewed the 30-minute documentary and completed the post-survey, which was nearly identical to the pre-survey minus the demographic questions. The post-survey added two questions to assess participants’ previous knowledge of Cherokee teachings highlighted in the film, including the proper way to harvest plants for cultural use and elemental understandings of the natural world (i.e., the properties and cultural significance of soil, air, water, and fire). We calculated percentage of participants in each response category both before and after viewing the PhotoVoice video. Statistical inference was made using paired t-tests. We examined the entire sample and also stratified by sex or age ≥ 50 years.

Results

Medicine Keeper Interviews

We present the main themes that emerged from the interviews with the Medicine Keepers in Table 1. The Medicine Keepers verified and discussed collectively these five themes in the focus group interview, and Carroll subsequently featured them in the still-image documentary. They include: 1) the respectful and responsible use of natural resources in order to ensure their health (Stewardship Ethic), 2) a critique of prevalent cattle grazing leases on Cherokee Nation tribal lands (Tribal Land Management), 3) increased physical restrictions with regard to gathering wild plants (Resource Access), 4) decreased overall health today as compared to previous generations that practiced subsistence-based lifestyles (Health and Subsistence), and 5) landscape and ecological changes that inhibit Cherokee resource use (Environmental Change).

Open coding of the individual Medicine Keeper interviews revealed numerous sub-themes that Carroll also incorporated into the documentary. One elder stressed that land conservation has associations with the continued use of the Cherokee language (“The language goes along with our culture. We’ve got names for all these plants…and if we don’t protect that, we’re going to lose it all”). This elder also expressed a desire for a comprehensive tribal land conservation plan that would include a tribal national park. Numerous elders expressed critical perspectives on economic development that threatens forests, and voiced their desire for tribal land to be left in its natural state to support wild medicines. Many also commented that all plants have medicinal value to Cherokees, as well as the perspective that medicine resides in other beings besides plants—for instance, in animals, water, and soil. Elders also conveyed uniquely Cherokee understandings of healing (“Our plant medicine doesn’t just cover the illness up [like Western medicine], it heals you from the inside out”), and an overall reliance upon the land for health (“Health comes from the land, and how we take care of the people and the land”). Two elders spoke specifically of the need to honor and love the land (“See, this stuff [plants, animals, land] needs loving—just as much as me and you need loving;” “We need to honor the earth. The ancestors said the Creator put a spirit in the earth”).

Surveys

The Medicine Keepers’ perspectives on critical environmental issues in the Cherokee Nation significantly changed those of the tribal citizens surveyed for this project in key domains, although some domains showed little to no change. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of survey participants, most of whom were at least 50 years of age (58%), female (70%), and employed at least part-time (54%). Forty-two percent of participants had completed some college and 28% had completed a Bachelor’s degree or higher. The majority of participants lived within the fourteen-county Cherokee Nation area (61%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of 87 participants who viewed the PhotoVoice video

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 18-29 | 8 |

| 30-39 | 14 |

| 40-49 | 20 |

| 50-59 | 32 |

| 60+ | 26 |

| Female | 70 |

| Employed full- or part-time | 54 |

| Completed education1 | |

| Less than high school | 6 |

| High school or GED | 24 |

| 13-15 years (some college or vocational school) | 42 |

| 16+ years (Bachelor’s degree or higher) | 28 |

| Residence during past 12 months2 | |

| Within 14-county Cherokee Nation area | 61 |

| In Oklahoma but outside Cherokee Nation | 21 |

| Outside Oklahoma | 18 |

missing;

missing

As shown in Table 3, the great majority of participants (80-97%) reported at least some concern for environmental issues prior to viewing the documentary. Similarly, before the video, most participants (85%) believed certain plants would disappear if they were not used for cultural purposes and most (93%) agreed that Cherokee Nation should buy lands to preserve plants used in traditional culture; however, fewer participants (67%) felt that land conservation could be connected to the survival of the Cherokee language. Willingness to conserve tribal lands if it meant reduced funding for other Cherokee Nation services was mixed prior to viewing the video, ranging from 22-61%.

Table 3.

Opinions about the environmental issues, the connection between conservation and Cherokee culture, and trade-offs for conservation of tribal lands: pre- and post-viewing of the PhotoVoice video

| Opinion | Pre-video % |

Post-video % |

Mean Difference* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental issues | |||

|

| |||

| How much health of your community where you live is affected by the condition of the surrounding natural environment | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.2) | ||

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | |

| A little | 6 | 6 | |

| Some | 21 | 16 | |

| A lot | 73 | 78 | |

| If we take care of the land, it will take care of us | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 5 | 3 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 2 | |

| Agree | 15 | 16 | |

| Strongly agree | 80 | 78 | |

| I am frustrated about the ways industries treat the environment | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 2 | |

| Disagree | 3 | 2 | |

| Agree | 30 | 30 | |

| Strongly agree | 66 | 65 | |

| As a Cherokee citizen, I have a moral obligation to protect the natural environment | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 2 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 2 | |

| Agree | 37 | 35 | |

| Strongly agree | 60 | 60 | |

| Impact of livestock, such as cattle, on health of the land | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) | ||

| Not at all | 6 | 2 | |

| A little | 15 | 3 | |

| Some | 33 | 28 | |

| A lot | 47 | 66 | |

| I am concerned about local environmental issues in the Cherokee Nation | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0 | |

| Disagree | 8 | 3 | |

| Agree | 45 | 47 | |

| Strongly agree | 45 | 50 | |

| Land conservation, such as preserving tribal lands in their undeveloped condition, should be a tribal priority for the Cherokee Nation | 0.2 (0.0, 0.3) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0 | |

| Disagree | 5 | 1 | |

| Agree | 52 | 45 | |

| Strongly agree | 43 | 53 | |

|

| |||

| Connection between conservation and Cherokee culture | |||

|

| |||

| Land conservation, such as preserving undeveloped areas, could be connected to the survival of the Cherokee language | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | ||

| Not at all | 15 | 5 | |

| A little | 18 | 7 | |

| Some | 37 | 38 | |

| A lot | 30 | 50 | |

| Certain plants will disappear if Cherokees do not continue to use them for cultural purposes | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 6 | 3 | |

| Disagree | 9 | 6 | |

| Agree | 37 | 21 | |

| Strongly agree | 48 | 70 | |

| The Cherokee Nation should buy lands to preserve plants used in our traditional culture in activities such as medicine, ceremony, cooking, or crafts | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0 | |

| Disagree | 6 | 2 | |

| Agree | 45 | 29 | |

| Strongly agree | 48 | 69 | |

|

| |||

| Tradeoffs for conservation of tribal lands | |||

|

| |||

| Willingness to conserve tribal lands if it meant reducing funding for Cherokee Nation education programs by 10% | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 9 | 7 | |

| Disagree | 30 | 26 | |

| Agree | 47 | 42 | |

| Strongly agree | 14 | 26 | |

| Willingness to conserve tribal lands if it meant reducing funding for Cherokee Nation education programs by 20% | 0.2 (0.0, 0.3) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 28 | 21 | |

| Disagree | 39 | 40 | |

| Agree | 24 | 26 | |

| Strongly agree | 9 | 14 | |

| Willingness to conserve tribal lands if it meant reducing funding for Cherokee Nation health services by 10% | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 19 | 15 | |

| Disagree | 42 | 30 | |

| Agree | 28 | 37 | |

| Strongly agree | 11 | 17 | |

| Willingness to conserve tribal lands if it meant reducing funding for Cherokee Nation health services by 20% | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 38 | 23 | |

| Disagree | 40 | 47 | |

| Agree | 15 | 19 | |

| Strongly agree | 7 | 12 | |

Possible mean difference range −3 to 3; a positive value indicates higher agreement in the post- vs. pre-video opinion; CI = confidence interval

Participants had similar opinions both before and after the video regarding how the health of the community affects the surrounding environment; believing if they take care of the land, it will take care of them; being frustrated about the ways industries treat the environment; and believing they have a moral obligation to protect the environment. However, participants showed significantly more agreement after, compared with before, the video regarding the impact of livestock on the health of the land (p<0.01), concern about local environmental issues in the Cherokee Nation (p=0.04), and land conservation being a tribal priority for the Cherokee Nation (p=0.01).

Participants also showed a stronger agreement regarding a connection between land conservation and Cherokee culture after, compared with before, viewing the video. Specifically, participants agreed more that land conservation could be connected to the survival of the Cherokee language (p<0.01), certain plants will disappear if Cherokees do not continue to use them for cultural purposes (p<0.01), and the Cherokee Nation should buy lands to preserve plants used in traditional culture activities (p<0.01).

Participants showed more support after the video for the conservation of tribal lands in the face of tradeoffs such as reduced funding for other Cherokee Nation services (p<0.01). However, even after the video, a substantial portion of participants (33-70%) disagreed with reduced funding for Cherokee Nation education programs or health services in favor of tribal land conservation. All results were similar when stratified by sex or age ≥ 50 years (data not shown).

As shown in Table 3, the highest amount of change survey participants made in their responses after viewing the PhotoVoice video occurred among four questions: 1) How much do you agree with this statement: “The Cherokee Nation should buy lands to preserve plants used in our traditional culture in activities such as medicine, ceremony, cooking, or crafts”? 2) How much do you agree with this statement: “Certain plants will disappear if Cherokees don’t continue to use them for cultural purposes”? 3) How much impact do you think livestock, such as cattle, have on the health of the land? 4) Do you think that land conservation, such as preserving undeveloped areas, could be connected to the survival of the Cherokee language?

Discussion

Changes in participants’ answers to the above four questions point to specific issues highlighted in the Medicine Keepers’ video. With regard to the first question on whether the Cherokee Nation should buy lands to preserve culturally-significant plants, participants’ response changes indicate a higher level of overall support for tribal conservation initiatives after viewing the video, specifically in the form of purchasing lands. This is likely related to the idea mentioned by two Medicine Keepers regarding the purchase of lands for a Cherokee National Park, which would provide protection for critical ecosystems and medicinal plants.

For the second question, the change in responses indicates agreement with two of the Medicine Keepers’ statements in the video conveying the importance of the continued use of plants, lest they disappear (Stewardship Ethic, Table 1). This perspective on the sustainable harvest of wild plants as contributing to the health and continuance of certain plant populations is well-founded among Indigenous traditional resource management studies (Turner 2005; Anderson 2006; Kimmerer 2013), and highlights the uniqueness of Indigenous conservation perspectives that do not preclude respectful human use of flora and fauna.

The change in the third question addresses numerous statements in the video regarding the prevalence of cattle grazing on Cherokee tribal lands and the ecological impacts this activity has had during the elders’ lifetimes (Tribal Land Management, Table 1). While many Oklahoma residents may take for granted the pervasiveness of cattle pastures today, Cherokee elders remember a time when fences and cows did not dominate the landscape, and they state in the video that this activity on tribal lands contributes to the loss of important Cherokee plants.

The last question reflects the previously mentioned statement regarding the connection between land conservation and the Cherokee language. As expressed by one elder, if Cherokees do not protect culturally-significant plants, their Cherokee names—and thus the knowledge conveyed through the language—will be lost. Numerous works support this assertion regarding the interdependency of language, knowledge, and the environment, emphasizing the place-based nature of many Indigenous languages (Basso 1996; Maffi 2001). The change in responses to this question was the highest of all and suggests that participants had not previously made this critical link between the health of the land and the status of the Cherokee language.

The implications of this study are far-reaching, and include effective strategies for identifying elder knowledge and perspectives on important issues through participatory, community-based projects; improving human and ecological health based on ancestral knowledge; informing tribal policy and decision-making drawing on elder knowledge and perspectives; and aiding in the preservation and perpetuation of ancestral knowledge carried by tribal elders via innovative technology and visual storytelling. We elaborate on each of these below.

Other studies have used PhotoVoice with Indigenous communities in the United States to identify the perspectives of tribal citizens on health, ranging from food insecurity (Jernigan et al. 2012) to community spaces (Jennings and Lowe 2013). These studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of PhotoVoice in elucidating Indigenous community concerns in ways that center community-defined issues and their potential solutions. Our study builds on the success of this method with Indigenous communities, and further integrates the foundational health focus of PhotoVoice with ecological concerns.6

Numerous studies with Indigenous communities have also explored how efforts to improve human health should include the health of the land (Parlee et al. 2005; Donatuto et al. 2016). Other work draws upon this holistic understanding of health to explore the link between land conservation and human health (Maller et al. 2006; Frumkin and Louv 2007; Kelly and Bliss 2009; Hansen-Ketchum 2015). More broadly, researchers have determined that human health depends on global biodiversity to buffer environmental stresses and ensure the favorable conditions necessary to life (e.g., healthy and plentiful food supplies, clean air and water, climate regulation) (Chivian and Bernstein 2008).

Although scholars have highlighted the need for ancestral or traditional knowledge to inform Indigenous policy on community health and the environment (Chino and DeBruyn 2006; Tsosie 2010), few studies have identified and employed specific methods to facilitate this process. While we recognize that many tribes may already draw upon ancestral teachings to guide their decisions as nations (see, e.g., Tomblin 2016), our study offers one possible avenue for connecting elder knowledge and governmental policy, specifically in the realm of tribal land conservation. Although the Cherokee Nation continues to implement profit-driven land management programs such as cattle grazing leases on tribal lands, the PhotoVoice video conveys elder perspectives on these activities, suggests alternatives, and seeks to influence decision-makers who may not otherwise think critically about such practices. We have used this project and the survey data to discuss with Cherokee Nation officials how their constituency has reacted favorably to elder perspectives. These conversations work toward the larger goal of centering ancestral knowledge and values within tribal governance structures (see Carroll 2015).

Lastly, tribal communities have long been concerned with the preservation and perpetuation of ancestral knowledge carried by tribal elders. Recent work in the area of Indigenous land education has sought to revitalize such knowledge systems and the land-based practices that inform them (Tuck et al. 2014; Wildcat et al. 2014). Our study aligns with this overall goal, and offers an example of how technology and visual storytelling can aid in the process of preserving and perpetuating tribal knowledge.

This study benefited from the input and direction of a formally constituted body of Cherokee elders. In addition, two members of the research team are Cherokee Nation citizens (Carroll and Garroutte); their familiarity with the political, social, and natural terrain of the research site conferred another strength. While our convenience sampling raises unanswerable questions about representativeness, we hope that the magnitude and diversity of attendance at the annual tribal holiday helped mitigate this limitation. Soliciting research participants at this event likely permitted access to a sampling pool that combined both local Cherokee citizens with their more distantly-residing counterparts to an extent that could be duplicated at no other venue.

In sum, this study shows that PhotoVoice is an effective method for Indigenous elders to communicate their environmental knowledge and perspectives, and that this method of communication can significantly change the views of other tribal citizens who may not possess the same types or degree of ancestral knowledge. Although a relatively brief intervention, the 30-minute documentary achieved a remarkably large effect. The implication for tribal health and land use policy is that presenting small packages of knowledge can create big change. If this type of educational intervention could be used more extensively, major changes in tribal policy and planning could occur as informed by elder knowledge and perspectives.

Conclusion

Tribes today are defining their agendas in arenas that were once controlled by the federal government. Drawing on ancestral philosophies to reclaim tribal institutions and guide decisions about public health marks a critical era in American Indian history. Through the perspectives of Cherokee elders, this study highlights the connections between land conservation and tribal health in order to make explicit their interdependence and to foster support from Cherokee Nation policymakers. By using qualitative and quantitative methods, we aim to broadcast traditional Cherokee land-based values while providing statistical data that speak the language of policy. And although the past and present support of the Medicine Keepers’ environmental education initiatives by the Cherokee Nation indicates a degree of receptiveness to conservation policies informed by the group’s ancestral knowledge and values, the results herein point to the opportunities that tribal policymakers have to help develop more far-reaching visions.

Our study uniquely employs PhotoVoice to explore an Indigenous land ethic as articulated by knowledge-keepers and it is the first to measure how tribal citizens’ knowledge and values about tribal land use policies may change as they encounter this ethic. Our results call for further research to aid tribes in defining their values relevant to health, to land use, and to the intersections between the two. Partnerships with elders and knowledge-keepers that produce novel ways of disseminating ancestral values within and beyond Indigenous communities offer promising possibilities for translating such values into policies that honor them.

Acknowledgments

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to stipulations made by the Cherokee Nation Institutional Review Board (CNIRB), but are available from the corresponding author with approval from the CNIRB on reasonable request.

Footnotes

See, for example, Ishiyama (2003) and Lewis (2007) on the Skull Valley Goshute Tribe’s controversial decision to store nuclear waste on their reservation.

We published a brief description of the PhotoVoice project accompanied by a photo essay in the journal Langscape (Carroll et al. 2016). The full video is available on YouTube (https://youtu.be/B2h_CUF9scc).

See also Hardbarger (2016), who used PhotoVoice to highlight the perspectives of Cherokee youth on sustainability and community development.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Altman HM, Belt TN. Tohi: The Cherokee Concept of Well-Being. In: Lefler LJ, editor. Under the Rattlesnake: Cherokee Health and Resiliency. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press; 2009. pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MK. Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arquette M, Cole M, Cook K, LaFrance B, Peters M, Ransom J, Sargent E, Smoke V, Stairs A. Holistic Risk-based Environmental Decision Making: A Native Perspective. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110(Suppl 2):259–264. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso K. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. Native Enclosures: Tribal National Parks and the Progressive Politics of Environmental Stewardship in Indian Country. Geoforum. 2014a;53:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. Shaping New Homelands: Environmental Production, Natural Resource Management, and the Dynamics of Indigenous State Practice in the Cherokee Nation. Ethnohistory. 2014b;61(1):123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. Roots of Our Renewal: Ethnobotany and Cherokee Environmental Governance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, the Cherokee Nation Medicine Keepers Cherokee Voices for the Land. Langscape. 2016;5(2):68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K, Belgrave L. Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, Marvasti AB, McKinney KD, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012. pp. 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chino M, DeBruyn L. Building True Capacity: Indigenous Models for Indigenous Communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):596–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivian E, Bernstein A. Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donatuto J, Campbell L, Gregory R. Developing Responsive Indicators of Indigenous Community Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016;13(9):899. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin H. Beyond Toxicity: Human Health and the Natural Environment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin H, Louv R. The Powerful Link Between Conserving Land and Preserving Health. Land Trust Alliance Special Anniversary Report. 2007 www.lta.org.

- Garrett MT. Understanding the Medicine of Native American Traditional Values: An Integrative Review. Counseling and Values. 1999;43(2):84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H, Stamler LL. Contemporary Perceptions of Health from an Indigenous (Plains Cree) Perspective. Journal of Aboriginal Health. 2010;6(1):6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Ketchum P. Engaging with Nature in the Promotion of Health. In: Hallstrom LK, Guehlstorf NP, Parkes MW, editors. Ecosystems, Society, and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence, and Integration. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2015. pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hardbarger T. Ph D Dissertation. Arizona State University; 2016. Sustainable Communities: Through the Lens of Cherokee Youth. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama N. Environmental Justice and American Indian Tribal Sovereignty: Case Study of a Land-use Conflict in Skull Valley, Utah. Antipode. 2003;35(1):119–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings D, Lowe J. Photovoice: Giving Voice to Indigenous Youth. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2013;11(3):521–537. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, Salvatore AL, Styne DM, Winkleby M. Addressing Food Insecurity in a Native American Reservation Using Community-based Participatory Research. Health Education Research. 2012;27(4):645–655. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SL. Native American Traditional and Alternative Medicine. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2002;583(1):195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn-John M, Koithan M. Living in Health, Harmony, and Beauty: The Diné (Navajo) Hózhó Wellness Philosophy. Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 2015;4(3):24–30. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EC, Bliss JC. Healthy Forests, Healthy Communities: An Emerging Paradigm for Natural Resource-dependent Communities? Society and Natural Resources. 2009;22(6):519–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer RW. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DR. Skull Valley Goshutes and the Politics of Nuclear Waste: Environment, Identity, and Sovereignty. In: Harkin ME, Lewis DR, editors. Native Americans and the Environment: Perspectives on the Ecological Indian. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2007. pp. 304–342. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi L, editor. On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maller C, Townsend M, Pryor A, Brown P, St Leger L. Healthy Nature Healthy People: ‘Contact with Nature’ as an Upstream Health Promotion Intervention for Populations. Health Promotion International. 2006;21(1):45–54. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton BR. Trust in the Land: New Directions in Tribal Conservation. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parlee B, Berkes F, Gwich’in Tribe Health of the Land, Health of the People: A Case Study on Gwichin Berry Harvesting in Northern Canada. EcoHealth. 2005;2(2):127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin DC. The White Mountain Recreational Enterprise: Bio-Political Foundations for White Mountain Apache Natural Resource Control, 1945–1960. Humanities. 2016;5(3):58. [Google Scholar]

- Tsosie R. Cultural Sovereignty and Tribal Energy Development: Creating a Land Ethic for the Twenty-first Century. In: Smith SL, Frehner B, editors. Indians and Energy: Exploitation and Opportunity in the American Southwest. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press; 2010. pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck E, McKenzie M, McCoy K. Land Education: Indigenous, Post-Colonial, and Decolonizing Perspectives on Place and Environmental Education Research. Environmental Education Research. 2014;20(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Turner NJ. The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Yi WK, Tao ZW, Carovano K. Photovoice as a Participatory Health Promotion Strategy. Health Promotion International. 1998;13(1):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wildcat M, McDonald M, Irlbacher-Fox S, Coulthard G. Learning from the Land: Indigenous Land Based Pedagogy and Decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 2014;3(3):i–xv. [Google Scholar]

- Wood M, Welcker Z. Tribes as Trustees Again (Part I): The Emerging Tribal Role in the Conservation Movement. Harvard Environmental Law Review. 2008;32:373–432. [Google Scholar]