Abstract

Background

Over 100 million people worldwide suffer from birch pollen allergy. However, identification of molecular determinants driving Th2-biased allergic sensitization to Bet v 1, the major birch pollen allergen, remains elusive.

Objective

Here, we examined whether Bet v 1 or the pollen matrix is responsible for activation of antigen-presenting cells and the subsequent Th2 polarization, relevant in the process of allergic sensitization.

Methods

The allergenicity of Bet v 1 and of birch pollen extract (BPE) was addressed by stimulation of murine and human dendritic cells and by in vivo monitoring of Th2 polarization. Further, Bet v 1 was depleted from BPE by immunoprecipitation in order to analyze its involvement in the occurrence of a Th2 response.

Results

The allergen alone did neither stimulate dendritic cells in vitro nor induced Th2 polarization in vivo, even in the presence of the natural LPS concentration determined in the BPE. In contrast, BPE was shown to activate dendritic cells and strongly promoted a Th2 polarization. Even upon immunization with Bet v 1-depleted BPE the amount of induced Th2 cells remained unaltered.

Conclusion

This finding indicates that the Th2-polarizing potential of BPE is Bet v 1 independent; therefore, sensitization to Bet v 1 is induced by an as-yet-undetermined pollen compound or mechanism in the pollen environment. These data suggest that sensitization is not exclusively linked to the intrinsic properties of individual proteins. These findings are relevant in understanding allergic sensitization towards pollen allergens and might pave the way for future prophylactic approaches.

Keywords: Allergic sensitization, allergenicity, Th2 polarization, Bet v 1, birch pollen, pollen extract, LPS, TLR4, allergy prophylaxis

To the Editor

Birch (Betula verrucosa) pollen is the main cause of spring pollinosis in the temperate climate zone of the Northern Hemisphere. Approximately 95% of birch pollen-allergic patients are sensitized to Bet v 1, the major birch pollen allergen(1). However, it is not known if sensitization toward Bet v 1 results from its own intrinsic properties or from immunomodulatory pollen compounds co-delivered with the allergen. Therefore, we investigated whether Bet v 1 or the pollen matrix is responsible for activation of antigen-presenting cells and the subsequent Th2 polarization, relevant in the process of allergic sensitization.

Since dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent activators of adaptive immune responses, we sought to investigate their role in the process of allergic sensitization toward Bet v 1. For this purpose the antigen uptake and activation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (mBMDCs) as well as the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) was monitored in vitro. Concerning the latter, PBMCs were isolated either from healthy, non-atopic donors or atopic patients. Cells were stimulated either with recombinant Bet v 1.0101 (rBet v 1) produced in E. coli or with an aqueous birch pollen extract (BPE). We analyzed whether DC activation is triggered by the co-stimulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contaminations found in BPE, termed nLPS. Furthermore, we investigated the capacity of rBet v 1 and BPE to induce Th2 polarization using an in vivo sensitization model. The methodology can be found in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

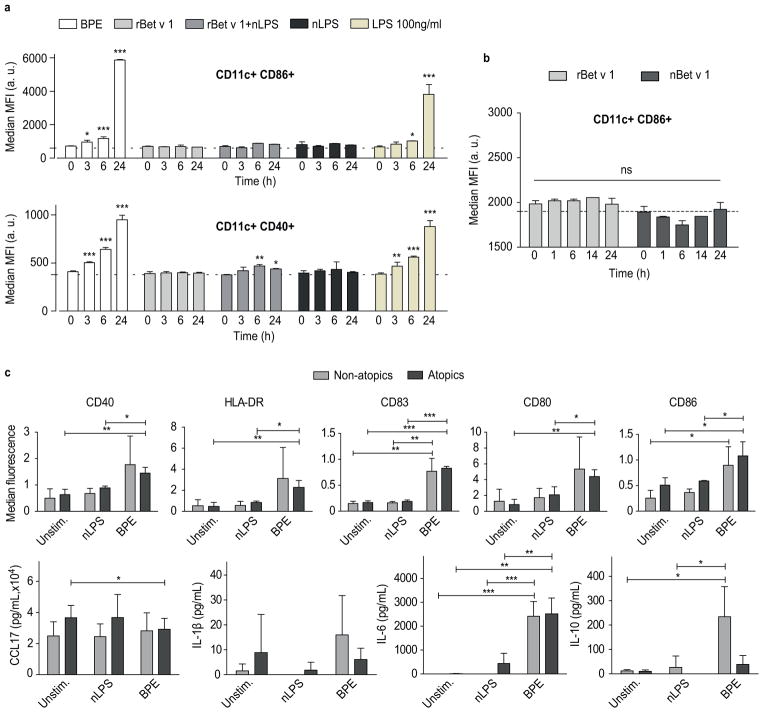

The upregulation of maturation markers (CD40 and CD86) expressed on CD11c+ mBMDCs was monitored over 24 hours (Fig 1a). The nLPS concentration was determined by using a NF-κB reporter gene assay (Fig E1). Here, 0.4 ng/ml of LPS had an equivalent capacity of 1 μg/ml of total soluble BPE protein to activate TLR4 and TLR2. As positive control, cells were incubated with LPS at a concentration of 100 ng/ml, 250-fold higher than nLPS. Compared to the basal activation of uninduced cells (Fig 1a, dashed line), BPE induced a time-dependent upregulation of CD86 and CD40. Stimulation with rBet v 1, even in the presence of nLPS, was not sufficient to mimic this effect. Because rBet v 1 represents just one of many isoforms found in BPEs, we investigated whether the activation of mBMDCs differs upon stimulation with a natural Bet v 1 isoform mixture (nBet v 1) purified from BPE (Fig 1b). No differences were observed between both natural and recombinant Bet v 1.

FIG 1.

Time-dependent activation of murine BMDCs stimulated with BPE or rBet v 1 +/− nLPS (a). Comparison of activation signal induced by rBet v 1 or nBet v 1 (b). Expression of maturation markers (c) and cytokine profile (d) of human moDCs stimulated with BPE. Error bars indicate mean and SEM (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001).

Furthermore, we analyzed the maturation (CD40, HLA-DR, CD80, CD83 and CD86) and secretion of the cytokines CCL17, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6, IL-12p70 and IL-23 of human moDCs upon stimulation with the major allergen. In parallel, the maturation-inducing effects of BPE were determined and compared to nLPS alone. The concentration of nBet v 1 in BPE was determined by ELISA and rBet v 1 was used in equivalent amounts. No maturation was induced by rBet v 1 (Fig E2a,b). In contrast, BPE induced an upregulation of maturation markers and IL-6 secretion in comparison to the unstimulated and/or nLPS-stimulated control (Fig 1c). Surprisingly, in moDCs derived from non-atopic donors the maturation effect was less pronounced, and a significant upregulation of IL-10 was observable. Without LPS co-stimulation neither secretion of IL-12p70 nor IL-23 by BPE stimulated moDCs was observable (data not shown).

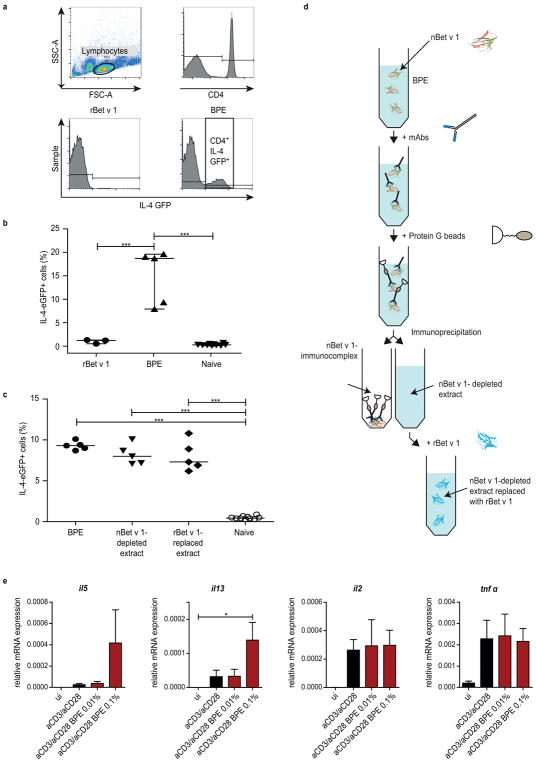

The finding that BPE but not rBet v 1 is able to effectively activate DCs raised the question whether pollen-derived compounds possess adjuvant-properties and thus contribute to the allergenicity of Bet v 1 in vivo. Therefore, we examined the capacity of BPEs and rBet v 1 to promote Th2 polarization. We utilized IL-4/GFP-enhanced transcript (4get) mice for monitoring the expression of the Th2 cytokine IL-4 in skin-draining inguinal lymphocytes (Fig 2a). Strikingly, rBet v 1 did not cause Th2 polarization, however BPE strongly induced IL-4 activation (Fig 2b). Since the involvement of the allergen itself as part of BPE in Th2 polarization was unclear, we addressed this question by immunizing 4get mice with a Bet v 1-depleted BPE (nBet v 1-depleted extract, Fig 2d and E3a–d) and a rBet v 1-reconstituted version (rBet v 1-replaced extract). Indeed, the Th2-promoting effect of the BPE remained even after the depletion (Fig 2c), indicating that Th2 polarization is induced via an allergen-independent co-stimulus. Additionally, the in vitro activation of mBMDCs from 4get mice was analyzed (Fig E4).

FIG 2.

Flow cytometry gating strategy used to quantify CD4+ IL-4 GFP+ T-cells (a). Percentage of IL-4-expressing CD4+ T-cells of mice immunized with rBet v 1 or BPE (b). Comparison of nBet v 1-depleted and rBet v 1-replaced extracts with untreated BPE (c); *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001. Schematic overview of nBet v 1-depletion of BPE using immunoprecipitation (d). mRNA expression of in vitro stimulated human naïve CD4+ T-cells with BPE (e).

To analyze potential direct effects of BPE on naïve CD4+ T-cells, we activated T-cells by treatment with αCD3/αCD28 and BPE. While the expression of αCD3/αCD28-stimulated Th2-specific cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 was enhanced upon additional stimulation with BPE (0,1%), BPE treatment did not affect the expression of the Th1-related cytokines IL-2 and TNFα.

Summarizing, we found that BPE efficiently activates murine and human DCs in vitro and is able to induce Th2 polarization in vivo and in vitro, whereas Bet v 1 lacks this property. These observations strongly support a role for the pollen context. Noteworthy, Th2 polarization upon immunization with BPE occurred Bet v 1-independently, indicating that the protein itself is not the sensitization-driving force.

Equivalent amounts of LPS (nLPS) in BPE are not capable of inducing DC maturation compared to the whole BPE, suggesting the observed activation cannot be attributed to LPS contaminations. However, LPS may not be the effective TLR-activating factor present in BPE since other contaminants are also present in pollen extracts. Previous studies demonstrating that pollen extracts promote maturation of TLR4-deficient DCs and that recognition of allergens is largely TLR-independent correlates with our observation(2–4). Hence, allergenicity may be explained by recognition of functional features of antigens(5–7). BPE-stimulated moDCs derived from non-atopic donors showed a significant reduction in maturation that may arise due to an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, which has been previously associated with downregulation of maturation activity(8).

Remarkably, Bet v 1-depleted BPE was still able to induce Th2 polarization. Therefore, we propose that Bet v 1 sensitization occurs as a result of additional immune interactions elicited by pollen- derived components that are not necessarily associated with the major allergen itself. Whether allergic sensitization toward Bet v 1 arises as a secondary effect of a pre-primed Th2 environment(3) and/or due to the high levels of Bet v 1 in BPEs remains to be determined in future studies(9). In this respect, the identification of Th2 polarizing compounds in pollen will be of utmost importance to understand the mechanisms of host-allergen source interactions and for the development of allergy prophylaxis.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

Bet v 1 alone is not able to induce DC activation in vitro and Th2 polarization in vivo

Birch pollen-induce Th2 polarization occurs via a Bet v 1-independent, pollen-derived stimulus

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Funds (FWF Projects P23417, P27589, and SFB F4610), by the University of Salzburg priority program “Allergy-Cancer-BioNano Research Centre,” by the Doctorate School Plus Program “Biomolecules” of the University of Salzburg, and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01-ES102906-01, REL).

Abbreviations

- 4get

IL-4/GFP-enhanced transcript

- BPE

birch pollen extract

- DC

dendritic cell

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mBMDC

murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- moDCs

monocyte-derived dendritic cells

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

References

- 1.Smith M, Jager S, Berger U, Sikoparija B, Hallsdottir M, Sauliene I, et al. Geographic and temporal variations in pollen exposure across Europe. Allergy. 2014;69(7):913–23. doi: 10.1111/all.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamijo S, Takai T, Kuhara T, Tokura T, Ushio H, Ota M, et al. Cupressaceae pollen grains modulate dendritic cell response and exhibit IgE-inducing adjuvant activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183(10):6087–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dittrich AM, Chen HC, Xu L, Ranney P, Connolly S, Yarovinsky TO, et al. A new mechanism for inhalational priming: IL-4 bypasses innate immune signals. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):7307–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi T, Gong X, Rossetto C, Shen C, Takabayashi K, Redecke V, et al. Induction and inhibition of the Th2 phenotype spread: implications for childhood asthma. J Immunol. 2005;174(9):5864–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(4):343–53. doi: 10.1038/ni.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer H, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Beutler B, Svanborg C. Mechanism of pathogen-specific TLR4 activation in the mucosa: fimbriae, recognition receptors and adaptor protein selection. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(2):267–77. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Llorente C, Munoz S, Gil A. Role of Toll-like receptors in the development of immunotolerance mediated by probiotics. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(3):381–9. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellinghausen I, Brand U, Steinbrink K, Enk AH, Knop J, Saloga J. Inhibition of human allergic T-cell responses by IL-10-treated dendritic cells: differences from hydrocortisone-treated dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(2):242–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schappi GF, Suphioglu C, Taylor PE, Knox RB. Concentrations of the major birch tree allergen Bet v 1 in pollen and respirable fine particles in the atmosphere. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):656–61. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.