Abstract

Currently, lacks of specificity and effectiveness remain the main drawbacks of clinical cancer treatment. Despite therapeutic advances in recent decades, clinical outcomes remain poor. Exosomes are nanosized particles with great potential for enhancing anticancer responses and targeted drug delivery. Exosomes modified through genetic or nongenetic methods can augment the cytotoxicity and targeting ability of therapeutic agents, thus improving their efficacy in killing cancer cells. In this review, we summarize recent research on engineering exosomes-based cancer therapy and discuss exosomes derived from tumors, mesenchymal stem cells, dendritic cells, HEK293T cells, macrophages, milk, and other donor cells. The antitumor effects of engineered-exosomes are highlighted and the potential adverse effects are considered. A comprehensive understanding of exosomes modification may provide a novel strategy for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Exosomes, cancer therapy, targeting, modification

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of disease-related death, and its occurrence is increasing [1]. Despite therapeutic advancement in recent decades, clinical outcomes of cancer remain poor because most patients are diagnosed at an advanced disease stage, and current chemotherapy confers only a modest survival advantage [2]. Most cancer treatments lack specificity and effectiveness. Exosomes are nanosized particles secreted by various cells and absorbed by recipient cells. Exosomes are rich in cargos, such as proteins, lipids, mRNA, and miRNA; exosomes protect these contents from degradation [3]. Exosomes play roles in extracellular communication and many physiological processes [4]. Because of their membrane structure, exosomes have potential as natural carriers of therapeutic agents for cancer therapy. Recent research confirms that engineering exosomes enhance the cancer-killing efficacy and the cancer-targeting ability of drugs, thus increasing the effectiveness of individual cancer therapies.

In this review, the modification of exosomes from different origins as therapeutic vehicles for cancer treatment is discussed, with particular emphasis on the distinct advantages of specific exosomes. We highlight the antitumor effect of the engineered exosomes and consider the potential adverse effects of each exosome type.

Tumor-derived exosomes

Tumor-derived exosomes (TEXs) are important mediators that modulate the contact between tumors and microenvironments [5]. Oncogenic mutations result in similar protein profile changes between exosomes and parental cells [6]. Tumor antigens can be presented through TEXs, indicating that TEXs could be modified for cancer immunotherapy. Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells that can initiate antigen-specific immunity. In one study, coinjected TEX-loaded DCs (DC-TEXs) were superior to lysate-loaded DCs at inducing an anticancer immune response; DC-TEXs therapy significantly prolonged the survival in a myeloid leukemia WEHI3B-bearing mouse model [7]. Furthermore, DC-TEXs inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma growth by increasing the number of T lymphocytes and level of interferon γ (IFN-γ) to improve the tumor microenvironment [8]. Shi et al. [9] found that combining PD-1 antibody with DC-TEXs enhanced the efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma by decreasing T-regulatory cells and blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.

The combination of TEXs and chemotherapeutics is commonly employed to enhance the efficacy of cancer treatment. Paclitaxel-loaded exosomes derived from prostate cancer cells through incubation increased cytotoxicity to parental cells more than free paclitaxel did, and the delivery partially depended on the surface proteins of exosomes [10]. Doxorubicin (DOX) was electroporated into breast and ovarian cancer-derived TEXs to generate exosomal DOX. The engineered exosomes exhibited a relatively high therapeutic index with suppression of breast and ovarian tumor growth and heart protection partially by limiting DOX across the myocardial endothelial cells in mice cancer models [11].

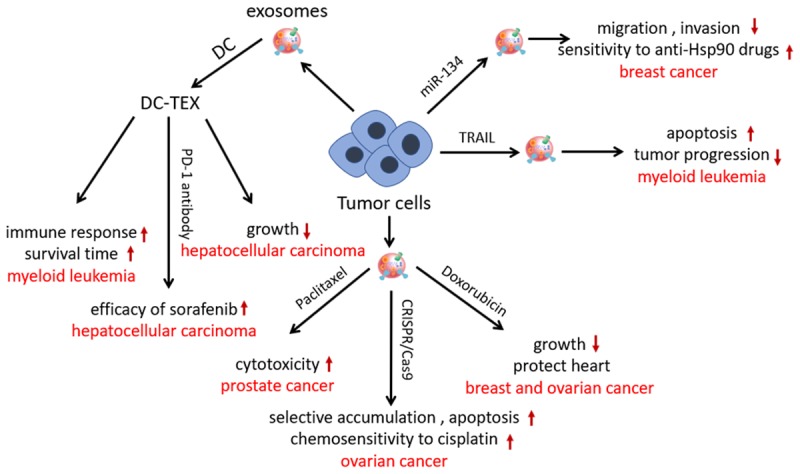

Genetically modifying cancer cells to generate TEXs may increase the toxicity and targeting ability of exosomes. TEXs derived from miR-134-transfected breast cancer cells inhibited migration and invasion of parent cells and enhanced sensitivity to anti-Hsp90 drugs [12]. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) selectively induces apoptosis of cancer cells. Rivoltini et al. [13] found that TEXs derived from myelogenous leukemia K562 cells transduced with lentiviral human membrane TRAIL induced apoptosis in cancer cells and inhibited tumor progression in SUDHL4-bearing mice, particularly through intratumor administration. CRISPR/Cas9-loaded TEXs derived from ovarian cancer cells through electroporation selectively accumulated in cancer sites and induced apoptosis in SKOV3-xenografted mice. Furthermore, enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin was observed through PARP-1 inhibition [14] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modification strategy and effect of tumor-derived exosomes in cancer therapy. DC-TEXs significantly prolonged the survival time, inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma growth and enhanced the efficacy of sorafenib in a cancer model. TEXs derived from miR-134-transfected breast cancer cells inhibited migration and invasion of parent cells and enhanced sensitivity to anti-Hsp90 drugs. TEXs derived from myelogenous leukemia cells transduced with TRAIL induced apoptosis in cancer cells and inhibited tumor progression. CRISPR/Cas9-loaded TEXs selectively accumulated in cancer sites, induced apoptosis, and enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin. Paclitaxel-loaded TEXs increased cytotoxicity to parental cells. DOX-loaded TEXs suppressed breast and ovarian tumor growth and protected the heart in mice cancer models.

TEXs are also a “double-edged sword” because of their property of facilitating cancer progression [15]. Prostate cancer cell-derived TEXs without chemotherapeutics may increase cancer cell viability [10]. TEXs are pertinent mediators for cancer metastasis and chemotherapeutic resistance [16]. Multiple myeloma (MM) exosomes enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression to establish a favorable bone marrow microenvironment for MM progression. Thus, further investigation is required to evaluate the safety and efficacy of TEXs. Moreover, melanoma cell-derived exosome-like vesicles could not be engineered using a cholesterol anchor to functionally deliver miRNA and siRNA, indicating that a deeper understanding of the biomolecular delivery mechanism of exosomes is required [17].

Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)-derived exosomes have great therapeutic potential in cell-free therapy, including tissue injury repair, inflammation amelioration, and cancer treatment [18,19]. Exosomal cargos, such as proteins, mRNAs, and miRNAs, are transferred from MSCs to target cells, altering the behavior of recipient cells through various pathways. Their considerable production of exosomes allows MSCs to be prospective candidates in the large-scale generation of exosomes for cancer therapy.

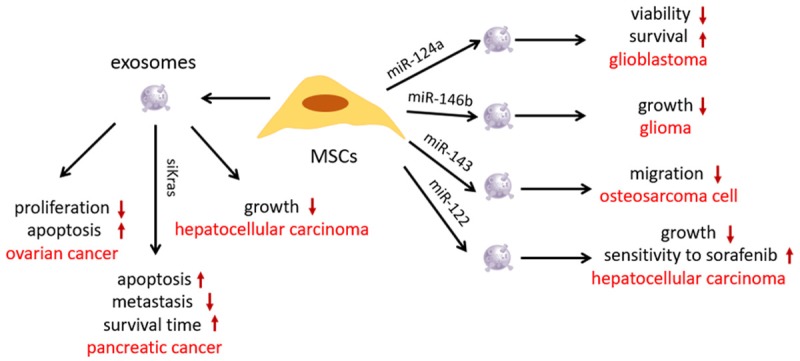

Native MSCs-derived exosomes exhibit cancer suppression ability. For example, adipose MSC (AMSC)-derived exosomes have been shown to restrain the proliferation ability and induce the apoptosis signaling of ovarian cancer cells [20]. Moreover, AMSC-derived exosomes were shown to promote NKT-cell antitumor responses for the suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma growth [21]. Genetic modification is the most common strategy in MSCs-derived exosomes-based cancer therapy through transfection of miRNA or siRNA. Exosomes from miR-124a-transfected MSCs significantly were found to reduce the viability of glioma stem cells and increase survival of mice with glioblastoma [22]. Similarly, miR-146b overexpressing MSCs-derived exosomes remarkably inhibited glioma xenograft growth in a rat model [23]. Shimbo et al. [24] found that miR-143 transfected-human bone marrow MSCs-derived exosomes suppressed the migration of 143B osteosarcoma cells. Bone marrow MSCs-derived exosomes were electroporated with siKRASG12D-1-targeting oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer, which induced apoptosis of Panc-1 cells in vitro. Administration of the modified exosomes in vivo inhibited the expression of KRAS, prolonged survival, and reduced metastasis in mice models with mild lesions of inflammation in normal tissue. Treatment efficacy improved when combined with gemcitabine [25]. Furthermore, miRNA-transfected MSCs-derived exosomes can improve chemosensitivity. Lou et al. [26] found that miR-122 was effectively packaged into exosomes via miR-122-transfecting AMSCs. The miR-122-loaded exosomes significantly increased the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib, leading to enhanced growth inhibition of tumor in vivo (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Roles of MSCs-derived exosomes in cancer treatment. AMSC-derived exosomes restrained the proliferation ability and induced apoptosis signaling of ovarian cancer cells. AMSC-derived exosomes promoted antitumor responses for the growth suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma. MSCs-derived exosomes, electroporated with siKRAS, induced apoptosis of Panc-1 cells, prolonged survival, and reduced metastasis in mice models. Exosomes from miR-124a-transfected MSCs reduced the viability of glioma stem cells. Treatment with miR-146b overexpressing MSCs-derived exosomes inhibited glioma xenograft growth. miR-143-transfected MSCs-derived exosomes suppressed the migration of osteosarcoma cell. miR-122-loaded exosomes significantly increased the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib.

Before engineering MSCs-derived exosomes, the potential contribution of exosomes to cancer progression should be mentioned. Roccaro et al. [27] found that MM bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitated MM progression with higher levels of oncogenic proteins, cytokines, and adhesion molecules than exosomes from normal cells. One study revealed that bone marrow MSCs-derived exosomes promoted tumor growth in vivo by increasing angiogenesis [28]. The supportive role of MSCs-derived exosomes in cancer progression requires further exploration.

DCs-derived exosomes

DCs play a vital role in antitumor immunity [29]. Compared with DCs, DCs-derived exosomes have distinct advantages in cancer immunotherapy, such as enriched peptide-MHC-II complexes, high stability, and resistance to immunosuppressive molecules [30]. DCs-derived exosomes may stimulate T-cell responses through direct and indirect routes, which improves antitumor immunity. Researchers have found that exosomes from DCs could promote natural-killer cell activation and proliferation and induce tumor regression [31]. Compared with direct treatment with natural DCs-derived exosomes, further modification of these exosomes exhibits enhanced immunostimulatory characteristics in cancer therapy.

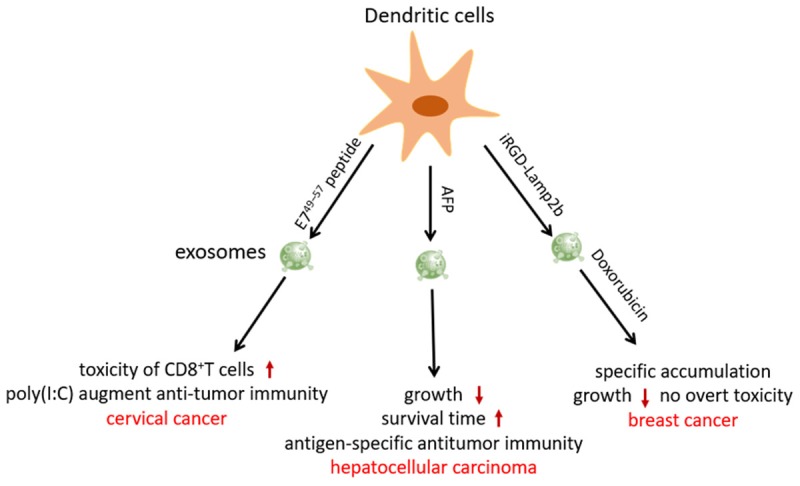

A study revealed that compared with tumor-derived exosomes, exosomes derived from DCs induced stronger CD8+ CTL responses and antitumor immunity [32]. Chen et al. [33] found that exosomes from E749-57 peptide-pulsed DCs enhanced the toxicity of CD8+ T cells on TC-1 tumor cells, and the supplement of poly(I:C) significantly augmented antitumor immunity in cervical cancer. Lu et al. [34] transfected mouse DCs with a lentivirus-expressing murine alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) gene to generate AFP-enriched exosomes. The engineered exosomes triggered potent antigen-specific antitumor-immune responses, as indicated by remarkably more IFN-γ-expressing CD8+ T lymphocytes, higher levels of IFN-γ and interleukin (IL)-2, fewer CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, decreased levels of IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β in tumor sites. Intravenous administration of AFP-enriched exosomes significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in a hepatocellular carcinoma model.

For enhanced cancer targeting and improved therapeutic effects, researchers have attempted to modify the surface of exosomes through gene transfection. LAMP2b, an exosomal membrane protein, fused to αv integrin-specific iRGD peptide was overexpressed in immature mouse DCs (imDCs). Exosomes purified from imDCs were then loaded with DOX through electroporation. The engineered exosomes efficiently delivered DOX to αv integrin-positive breast cancer cells in vitro. Moreover, DOX specifically accumulated in tumor tissues by intravenous administration of targeted exosomes, leading to inhibition of tumor growth without overt toxicity [35] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Application of engineering DCs-derived exosomes in cancer therapy. Exosomes from E749-57 peptide-pulsed DCs enhanced the toxicity of CD8+ T cells on TC-1 tumor cells, and the supplement of poly(I:C) significantly augmented antitumor immunity in cervical cancer. AFP-enriched exosomes triggered potent antigen-specific antitumor-immune responses, inhibited tumor growth, prolonged survival in a mice hepatocellular carcinoma model. iRGD-LAMP2b overexpressing imDCs-derived exosomes efficiently delivered DOX to αv integrin-positive breast cancer cells and specifically accumulated in tumor tissues, leading to inhibition of tumor growth without overt toxicity.

Exosomes derived from ovalbumin-loaded DCs from MHCI-/- mice were found to induce the same level of antitumor immunity as wild-type exosomes in mice B16 melanoma, with similar tumor infiltrating T cells and overall survival time [36]. Thus, DCs-derived exosomes stimulate T-cell responses, irrespective of whether MHC molecules on exosomes are present. Therefore, modification of impersonalized DCs exosomes may have expanded application in cancer immunotherapy in the future.

HEK293T cells-derived exosomes

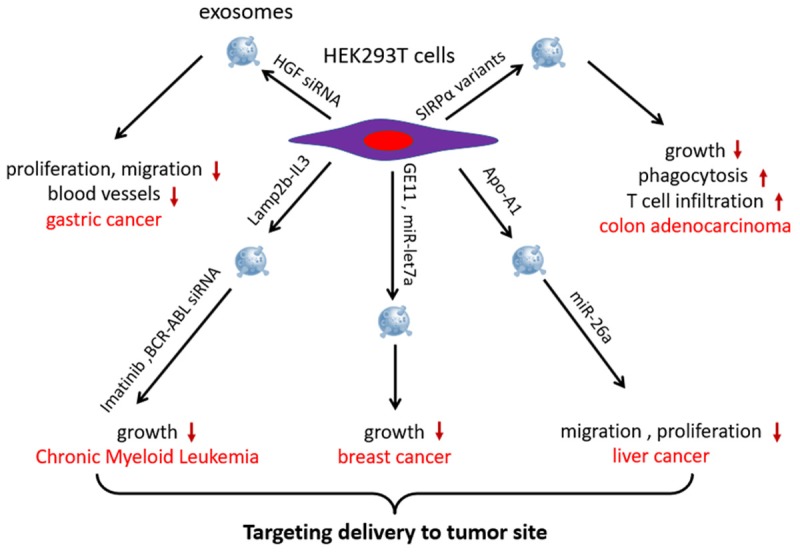

HEK293T cell lines are commonly used to express exogenous genes. Thus, exosomes derived from HEK293T cells are feasible vesicles for delivery of therapeutic molecules. The HGF-cMET pathway is involved in promoting the growth of both cancer cells and vascular cells. Researchers have transfected HEK293T cells with siRNA to pack HGF siRNA into exosomes. The HGF siRNA-loaded exosomes demonstrated a suppression effect on the proliferation and migration of both gastric cancer cells and vascular cells. Furthermore, exosomes were able to transfer HGF siRNA in vivo, decreasing the growth rates of tumors and blood vessels [37].

The most effective strategy of HEK239T cells-derived exosomes is their use for targeted anticancer agent delivery. The IL3 receptor is expressed in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) blasts. Thus, HEK293T cells were designed to express the exosomal protein LAMP2b fused to a fragment of IL-3 for generating targeted IL3 exosomes. IL3 exosomes selectively targeted CML cells and suppressed growth both in vivo and in vitro when loaded with Imatinib or BCR-ABL siRNA [38]. Another study found that exosomes from GE11 peptide-transfected HEK293T cells efficiently delivered miR-let7a to epidermal growth factor receptor-expressing breast cancer cells and inhibited cancer growth [39]. A similar study demonstrated that exosomes from Apo-A1-overexpressed HEK293T cells achieved functional delivery of miR-26a to scavenger receptor class B type 1-expressing liver cancer HepG2 cells, thus decreasing cell migration and proliferation [40].

Exosomes have also been engineered for increasing phagocytosis of cancer cells by macrophages. Most cancer cells express CD47 on the surface, which provides a “do not eat me” signal. Binding CD47 with signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) on innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, activates the “do not eat me” signal and causes tumors to escape from phagocytosis [41]. Koh et al. [42] found that exosomes from SIRPα variant-transfected HEK293T cells enhanced the phagocytosis of CT26.CL25 and HT29 tumor cells by macrophages and enhanced T-cell infiltration via antagonizing the interaction between CD47 and SIRPα, thereby inhibiting the growth of cancer in syngeneic mice models. Another study found that compared with the same dose of ferritin-SIRPα, the therapeutic index of exosomes harboring SIRPα against tumor growth was higher in CT26.CL25 and HT29 tumor-bearing mice [43] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

HEK293T cells-derived exosomes are used for enhancing cancer cells-killing efficacy and targeting ability of anticancer agents. HGF siRNA-loaded exosomes suppressed the proliferation and migration of both gastric cancer cells and vascular cells. Exosomes from SIRPα variant-transfected HEK293T cells enhanced the phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages and enhanced T-cell infiltration, inhibiting the growth of cancer in syngeneic mouse models. Exosomes derived from LAMP2b-IL-3-, GE11-, or Apo-A1 overexpressing HEK293T cells specifically delivered miRNA, siRNA, or drugs to tumor sites and inhibited CML, breast cancer, and liver cancer growth, respectively.

Macrophage-derived exosomes

Macrophage-derived exosomes can be packaged with various molecules for targeting cancer sites. Multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer has become a major challenge to successful chemotherapy, including complex cellular and physiological factors [44]. To overcome MDR in cancer treatment, paclitaxel was incorporated into macrophage-derived exosomes via sonication. A cytotoxicity increase of over 50 times in drug-resistant MDCKMDR1 (Pgp+) cells was demonstrated after paclitaxel-loaded exosomes were administered. A nearly complete colocalization between exosomes and pulmonary metastases was also observed, which was likely caused by specific proteins on the surface of macrophage-released exosomes [45]. For improving the targeting ability of exosomes, researches incorporated paclitaxel-loaded exosomes with aminoethylanisamide-polyethylene glycol to target the sigma receptor, which is overexpressed by lung cancer cells. The modified exosomes showed selective accumulation in cancer cells and resulted in a superior antitumor effect with stronger suppression of metastases growth and longer survival when compared with paclitaxel-loaded exosomes [46].

Milk-derived exosomes

Accumulating evidence has shown that milk-derived exosomes are alternatives for drug delivery in cancer therapy and easier to access than other donor cell-derived exosomes. Incubating exosomes is the most commonly employed method for loading drugs into exosomes. Exosomes loaded with paclitaxel via incubation showed higher tumor growth inhibition and lower systemic and immunologic toxicities than free paclitaxel did in A549-xenograft mice following oral administration [47]. A similar antitumor effect was observed in anthocyanidin-loaded exosomes on ovarian cancer cells [48]. Munagala et al. [49] demonstrated that exosomes loaded with withaferin A through incubation exhibited significantly higher growth-inhibitory effects against A549 tumor xenograft when compared with withaferin A alone. Moreover, folate, a tumor targeting ligand, increased the cancer cell targeting of the exosomes resulting in enhanced tumor reduction. In summary, loading chemotherapeutics into milk-derived exosomes is an efficient and cost-effective method to overcome several hurdles of drugs, such as poor oral bioavailability and cytotoxicity.

Exosomes of other origins

In addition to the aforementioned donor cells-derived exosomes, exosomes from specific cells have prospective application in particular cancer treatments. Cerebral endothelial cell-derived exosomes serve as promising candidates to deliver drugs across the blood-brain barrier for brain cancer treatment. Anticancer drugs or vascular endothelial growth factor siRNA-loaded exosomes were shown to efficiently decrease tumor growth in a xenotransplanted brain tumor model [50,51].

Many hepatocellular carcinoma cases arise with a background of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis with richly activated stellate cells [52]. Thus, specially modified exosomes from stellate cells may be used as tools to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Wang et al. [53] transfected exosomes derived from LX2 cells with miR-335-5p to produce Exo-miR-335-5p. Exo-miR-335-5p could inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and induce tumor shrinkage in vivo.

Reticulocyte-derived exosomes contain various membrane proteins, including transferrin receptors. Superparamagnetic nanoparticle-transferrin conjugation was added to serum to generate superparamagnetic nanoparticle-labeled exosomes (SMNC-EXOs) that could be separated from serum using a magnetic field. The results showed that DOX-loaded SMNC-EXOs efficiently enhanced cancer targeting under an external magnetic field and inhibited hepatoma 22 subcutaneous tumor growth in vivo [54].

Discussion

Two areas for improvement of cancer treatment are targeting and effectiveness. Exosomes are naturally endowed with efficient target homing to a tumor site, potentially attributable to their multivalent display of cell-derived surface moieties [13,55]. Furthermore, exosomes can selectively accumulate in cancer site through modification of their surface in order to express targeting molecules that bind to receptors on cancer cells. The combination of therapeutic drugs and exosomes exhibits increased cytotoxicity and more effective killing efficacy on cancer cells. Therefore, engineered exosomes show promise in cancer therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of therapeutic effects on cancer of various modified exosomes

| Exosomal cargos | Donor cells | Tumor models | Study outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-134 | Hs578Ts(i)8 (breast cancer) | Breast cancer | Inhibited migration and invasion of parent cells, enhanced sensitivity to anti-Hsp90 drugs | [12] |

| TRAIL | K562 (myelogenous leukemia) | B-cell lymphoma | Induced apoptosis in cancer cells and inhibited tumor progression | [13] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | SKOV3 (ovarian cancer) | Ovarian cancer | Selectively accumulated in cancer site, induced apoptosis, enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin | [14] |

| miR-124a | BM-MSC | Glioma | Reduced the viability of glioma stem cell and increased survival of mice with glioblastoma | [22] |

| miR-146b | MSC | Glioma | Inhibited glioma growth | [23] |

| miR-143 | BM-MSC | Osteosarcoma | Suppressed the migration of the 143B osteosarcoma cell | [24] |

| siKrasG12D-1 | BM-MSC | Pancreatic cancer | Induced apoptosis, prolonged the survival, reduced metastasis | [25] |

| miR-122 | AMSC | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Increased the sensitivity to sorafenib, enhanced growth inhibition | [26] |

| AFP | DC | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Triggered antigen-specific antitumor immune responses, inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival | [34] |

| Lamp2b-iRGD | ImDC | Breast cancer | Delivered DOX to αv integrin-positive breast cancer cells, specifically accumulated in tumor tissue, inhibited tumor growth | [35] |

| HGF siRNA | HEK293T | Gastric cancer | Suppressed the proliferation and migration of both gastric cancer and vascular cells | [37] |

| Lamp2b-IL3 | HEK293T | CML | Selectively targeted CML cells and suppressed growth when loaded with Imatinib or with BCR-ABL siRNA | [38] |

| GE11 peptide, miR-let7a | HEK293T | Breast cancer | Delivered miR-let7a to EGFR-expressing breast cancer cells and inhibited cancer growth | [39] |

| Apo-A1, miR-26a | HEK293T | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Delivered miR-26a to scavenger receptor class B type 1-expressing liver cancer cells, decreased migration and proliferation | [40] |

| SIRPα variants | HEK293T | Colon adenocarcinoma | Enhanced phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages, inhibited cancer growth | [42] |

| VEGF siRNA | Cerebral endothelial cell | Glioblastoma-astrocytoma | Inhibited VEGF in U-87 MG cells and inhibited tumor growth | [51] |

| miR-335-5p | LX2 stellate cell | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Inhibited HCC cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and induced HCC tumor shrinkage in vivo | [53] |

| Paclitaxel | LNCaP and PC-3 (prostate cancer) | Prostate cancer | Increased cytotoxicity to parental cells | [10] |

| Doxorubicin | MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer) STOSE (ovarian cancer) | Breast cancer ovarian cancer | Suppressed breast and ovarian tumor growth and protected heart | [11] |

| Paclitaxel | Macrophage | Lung carcinoma | Increased more than 50 times cytotoxicity in drug resistant MDCKMDR1 (Pgp+) cells | [45] |

| Paclitaxel | Milk | Lung cancer | Higher tumor growth inhibition and lower systemic and immunologic toxicities than free paclitaxel | [47] |

| Anthocyanidins | Milk | Ovarian cancer | Inhibited tumor growth more efficiently compared to Anthos alone | [48] |

| Withaferin A | Milk | Lung cancer | Higher growth-inhibitory effects against A549 tumor xenograft compared to withaferin A | [49] |

| Doxorubicin | Cerebral endothelial cell | Glioblastoma-astrocytoma | Inhibited tumor growth | [50] |

| Doxorubicin | Reticulocytes | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Enhanced cancer targeting under an external magnetic field and inhibited tumor growth in vivo | [54] |

Exosomes are promising nanovesicles for therapeutic molecular delivery in cancer therapy with low immunogenicity, high biocompatibility, high drug delivery efficacy, and low cytotoxicity to normal tissue. Many therapeutic agents, including miRNA, proteins, and chemotherapeutics, can be designed and engineered into exosomes to improve their killing and targeting ability to tumor sites.

Because exosomes are generated from parent cells and reflect the functional status of their origins, exosomes derived from different sources hold diverse applications in exosome-based cancer treatment. Thus, choosing the appropriate exosomes for further modification is crucial.

Various methods are employed to engineer exosomes. Electroporation is most commonly used for loading miRNA and siRNA into isolated exosomes. For genetic modification of donor cells, viruses or plasmid transfection may be employed. Incubation is useful for loading chemotherapeutics into exosomes. The development of robust and automated devices may be a promising approach for overcoming the expenses and labor requirements of engineering exosomes [56].

No standard procedures have been developed for isolating exosomes. Thus, standardized methods for isolating, engineering, storing, administering, and monitoring toxicity must be established before further clinical trials. Moreover, the potential oncogenicity of exosomes should be included in safety evaluations. Further investigation is required to observe any potential side effects after long-term use. Large-scale production of exosomes may improve the feasibility of clinical trials [25].

Acknowledgements

National Natural Science Foundation of China (81702439, 81572075), Postdoctoral science foundation of China (2016M600383), the Special Funded Projects of China Postdoctoral Fund (2017T100337).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye J, Xu J, Li Y, Huang Q, Huang J, Wang J, Zhong W, Lin X, Chen W, Lin X. DDAH1 mediates gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:1208–1224. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlassov AV, Magdaleno S, Setterquist R, Conrad R. Exosomes: current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, De Veirman K, Faict S, Frassanito MA, Ribatti D, Vacca A, Menu E. Multiple myeloma exosomes establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J Pathol. 2016;239:162–173. doi: 10.1002/path.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobb RJ, Hastie ML, Norris EL, van Amerongen R, Gorman JJ, Moller A. Oncogenic transformation of lung cells results in distinct exosome protein profile similar to the cell of origin. Proteomics. 2017:17. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu X, Erb U, Buchler MW, Zoller M. Improved vaccine efficacy of tumor exosome compared to tumor lysate loaded dendritic cells in mice. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E74–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao Q, Zuo B, Lu Z, Gao X, You A, Wu C, Du Z, Yin H. Tumor-derived exosomes elicit tumor suppression in murine hepatocellular carcinoma models and humans in vitro. Hepatology. 2016;64:456–472. doi: 10.1002/hep.28549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Rao Q, Zhang C, Zhang X, Qin Y, Niu Z. Dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes in combination with PD-1 antibody increase the efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma model. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saari H, Lazaro-Ibanez E, Viitala T, Vuorimaa-Laukkanen E, Siljander P, Yliperttula M. Microvesicle- and exosome-mediated drug delivery enhances the cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel in autologous prostate cancer cells. J Control Release. 2015;220:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadla M, Palazzolo S, Corona G, Caligiuri I, Canzonieri V, Toffoli G, Rizzolio F. Exosomes increase the therapeutic index of doxorubicin in breast and ovarian cancer mouse models. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2016;11:2431–2441. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2016-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien K, Lowry MC, Corcoran C, Martinez VG, Daly M, Rani S, Gallagher WM, Radomski MW, MacLeod RA, O’Driscoll L. miR-134 in extracellular vesicles reduces triple-negative breast cancer aggression and increases drug sensitivity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32774–32789. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivoltini L, Chiodoni C, Squarcina P, Tortoreto M, Villa A, Vergani B, Burdek M, Botti L, Arioli I, Cova A, Mauri G, Vergani E, Bianchi B, Della Mina P, Cantone L, Bollati V, Zaffaroni N, Gianni AM, Colombo MP, Huber V. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-armed exosomes deliver proapoptotic signals to tumor site. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3499–3512. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SM, Yang Y, Oh SJ, Hong Y, Seo M, Jang M. Cancer-derived exosomes as a delivery platform of CRISPR/Cas9 confer cancer cell tropism-dependent targeting. J Control Release. 2017;266:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun W, Luo JD, Jiang H, Duan DD. Tumor exosomes: a double-edged sword in cancer therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39:534–541. doi: 10.1038/aps.2018.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Challagundla KB, Wise PM, Neviani P, Chava H, Murtadha M, Xu T, Kennedy R, Ivan C, Zhang X, Vannini I, Fanini F, Amadori D, Calin GA, Hadjidaniel M, Shimada H, Jong A, Seeger RC, Asgharzadeh S, Goldkorn A, Fabbri M. Exosome-mediated transfer of microRNAs within the tumor microenvironment and neuroblastoma resistance to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stremersch S, Vandenbroucke RE, Van Wonterghem E, Hendrix A, De Smedt SC, Raemdonck K. Comparing exosome-like vesicles with liposomes for the functional cellular delivery of small RNAs. J Control Release. 2016;232:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Zhang K, Wu S, Cui M, Xu T. Focus on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: opportunities and challenges in cell-free therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:6305295. doi: 10.1155/2017/6305295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rani S, Ryan AE, Griffin MD, Ritter T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: toward cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 2015;23:812–823. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reza AM, Choi YJ, Yasuda H, Kim JH. Human adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal-miRNAs are critical factors for inducing anti-proliferation signalling to A2780 and SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38498. doi: 10.1038/srep38498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko SF, Yip HK, Zhen YY, Lee CC, Lee CC, Huang CC, Ng SH, Lin JW. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes suppress hepatocellular carcinoma growth in a rat model: apparent diffusion coefficient, natural killer T-cell responses, and histopathological features. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:853506. doi: 10.1155/2015/853506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang FM, Hossain A, Gumin J, Momin EN, Shimizu Y, Ledbetter D, Shahar T, Yamashita S, Parker Kerrigan B, Fueyo J, Sawaya R, Lang FF. Mesenchymal stem cells as natural biofactories for exosomes carrying miR-124a in the treatment of gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:380–390. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katakowski M, Buller B, Zheng X, Lu Y, Rogers T, Osobamiro O, Shu W, Jiang F, Chopp M. Exosomes from marrow stromal cells expressing miR-146b inhibit glioma growth. Cancer Lett. 2013;335:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimbo K, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Kato Y, Kubo T, Shimose S, Ochi M. Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendt M, Kamerkar S, Sugimoto H, McAndrews KM, Wu CC, Gagea M, Yang S, Blanko EVR, Peng Q, Ma X, Marszalek JR, Maitra A, Yee C, Rezvani K, Shpall E, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. Generation and testing of clinical-grade exosomes for pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight. 2018:3. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lou G, Song X, Yang F, Wu S, Wang J, Chen Z, Liu Y. Exosomes derived from miR-122-modified adipose tissue-derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:122. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0220-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Maiso P, Azab AK, Tai YT, Reagan M, Azab F, Flores LM, Campigotto F, Weller E, Anderson KC, Scadden DT, Ghobrial IM. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1542–1555. doi: 10.1172/JCI66517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu W, Huang L, Li Y, Zhang X, Gu J, Yan Y, Xu X, Wang M, Qian H, Xu W. Exosomes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity. 2013;39:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt JM, Andre F, Amigorena S, Soria JC, Eggermont A, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1224–1232. doi: 10.1172/JCI81137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viaud S, Terme M, Flament C, Taieb J, Andre F, Novault S, Escudier B, Robert C, Caillat-Zucman S, Tursz T, Zitvogel L, Chaput N. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote natural killer cell activation and proliferation: a role for NKG2D ligands and IL-15Ralpha. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hao S, Bai O, Yuan J, Qureshi M, Xiang J. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes stimulate stronger CD8+ CTL responses and antitumor immunity than tumor cell-derived exosomes. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, Lv M, Fang S, Ye W, Gao Y, Xu Y. Poly(I:C) enhanced anti-cervical cancer immunities induced by dendritic cells-derived exosomes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;113:1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Z, Zuo B, Jing R, Gao X, Rao Q, Liu Z, Qi H, Guo H, Yin H. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes elicit tumor regression in autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma mouse models. J Hepatol. 2017;67:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian Y, Li S, Song J, Ji T, Zhu M, Anderson GJ, Wei J, Nie G. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiltbrunner S, Larssen P, Eldh M, Martinez-Bravo MJ, Wagner AK, Karlsson MC, Gabrielsson S. Exosomal cancer immunotherapy is independent of MHC molecules on exosomes. Oncotarget. 2016;7:38707–38717. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Wang Y, Bai M, Wang J, Zhu K, Liu R, Ge S, Li J, Ning T, Deng T, Fan Q, Li H, Sun W, Ying G, Ba Y. Exosomes serve as nanoparticles to suppress tumor growth and angiogenesis in gastric cancer by delivering hepatocyte growth factor siRNA. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:629–641. doi: 10.1111/cas.13488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellavia D, Raimondo S, Calabrese G, Forte S, Cristaldi M, Patinella A, Memeo L, Manno M, Raccosta S, Diana P, Cirrincione G, Giavaresi G, Monteleone F, Fontana S, De Leo G, Alessandro R. Interleukin 3-receptor targeted exosomes inhibit in vitro and in vivo chronic myelogenous leukemia cell growth. Theranostics. 2017;7:1333–1345. doi: 10.7150/thno.17092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohno S, Takanashi M, Sudo K, Ueda S, Ishikawa A, Matsuyama N, Fujita K, Mizutani T, Ohgi T, Ochiya T, Gotoh N, Kuroda M. Systemically injected exosomes targeted to EGFR deliver antitumor microRNA to breast cancer cells. Mol Ther. 2013;21:185–191. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang G, Kan S, Zhu Y, Feng S, Feng W, Gao S. Engineered exosome-mediated delivery of functionally active miR-26a and its enhanced suppression effect in HepG2 cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:585–599. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S154458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao MP, Weissman IL, Majeti R. The CD47-SIRPalpha pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koh E, Lee EJ, Nam GH, Hong Y, Cho E, Yang Y, Kim IS. Exosome-SIRPalpha, a CD47 blockade increases cancer cell phagocytosis. Biomaterials. 2017;121:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho E, Nam GH, Hong Y, Kim YK, Kim DH, Yang Y, Kim IS. Comparison of exosomes and ferritin protein nanocages for the delivery of membrane protein therapeutics. J Control Release. 2018;279:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel NR, Pattni BS, Abouzeid AH, Torchilin VP. Nanopreparations to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:1748–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim MS, Haney MJ, Zhao Y, Mahajan V, Deygen I, Klyachko NL, Inskoe E, Piroyan A, Sokolsky M, Okolie O, Hingtgen SD, Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim MS, Haney MJ, Zhao Y, Yuan D, Deygen I, Klyachko NL, Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV. Engineering macrophage-derived exosomes for targeted paclitaxel delivery to pulmonary metastases: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Nanomedicine. 2018;14:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agrawal AK, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Spencer WA, Beck J, Gachuki BW, Alhakeem SS, Oben K, Munagala R, Bondada S, Gupta RC. Milk-derived exosomes for oral delivery of paclitaxel. Nanomedicine. 2017;13:1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Agrawal AK, Kyakulaga AH, Munagala R, Parker L, Gupta RC. Exosomal delivery of berry anthocyanidins for the management of ovarian cancer. Food Funct. 2017;8:4100–4107. doi: 10.1039/c7fo00882a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munagala R, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Gupta RC. Bovine milk-derived exosomes for drug delivery. Cancer Lett. 2016;371:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang T, Martin P, Fogarty B, Brown A, Schurman K, Phipps R, Yin VP, Lockman P, Bai S. Exosome delivered anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier for brain cancer therapy in Danio rerio. Pharm Res. 2015;32:2003–2014. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang T, Fogarty B, LaForge B, Aziz S, Pham T, Lai L, Bai S. Delivery of small interfering rna to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor in zebrafish using natural brain endothelia cell-secreted exosome nanovesicles for the treatment of brain cancer. Aaps J. 2017;19:475–486. doi: 10.1208/s12248-016-0015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang F, Li L, Piontek K, Sakaguchi M, Selaru FM. Exosome miR-335 as a novel therapeutic strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:940–954. doi: 10.1002/hep.29586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qi H, Liu C, Long L, Ren Y, Zhang S, Chang X, Qian X, Jia H, Zhao J, Sun J, Hou X, Yuan X, Kang C. Blood exosomes endowed with magnetic and targeting properties for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3323–3333. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syn NL, Wang L, Chow EK, Lim CT, Goh BC. Exosomes in cancer nanomedicine and immunotherapy: prospects and challenges. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lunavat TR, Jang SC, Nilsson L, Park HT, Repiska G, Lasser C, Nilsson JA, Gho YS, Lotvall J. RNAi delivery by exosome-mimetic nanovesicles-implications for targeting c-Myc in cancer. Biomaterials. 2016;102:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]