Abstract

Cholangiocarcinoma is a most lethal malignancy frequently resistant to chemotherapy. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/Ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) suicide gene therapy is a promising approach to treat different cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma. However drawbacks including low therapeutic gene expression and lack of precise targeted gene delivery limit the wide clinical utilization of the suicide gene therapy. We attempted to overcome these obstacles. We established the “proof-of-principle” of this concept via serial in-vitro experiments using human cholangiocarcinoma cells and then validated the new interventional oncology technique in vivo using mice harboring the same patient derived cholangiocarcinomas. Curative effects were evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging and confirmed by pathology and laboratory examinations. Intratumoral radiofrequency hyperthermia (RFH) significantly elevated the targeted expression of HSV-TK gene and further enhanced the therapeutic effects of direct intratumoral HSV-TK/GCV gene therapy, evident as the least number of survival tumor cells, smallest tumor size, and the highest apoptosis index in the combination treatment of HSV-TK plus RFH, compared to other control treatments. The novel combination of image-guided interventional oncology, RFH technology, and direct gene therapy may be valuable for the effective treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.

Keywords: Radiofrequency hyperthermia, HSV-TK, gene therapy, cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma is one of the deadest diseases worldwide with poor outcomes and an increasing mortality rate [1,2]. Surgery and direct curative liver transplant are the best options for patients with this difficult to cure malignancy. However, these treatments are unsuitable for patients suffering from metastatic cholangiocarcinoma [3]. Although chemotherapy is a beneficial aid for inoperable patients, the use of chemotherapy is still limited in many cases of cholangiocarcinoma, because of the low chemotherapeutic dose attained at the target using systemic delivery and the rapid development of drug resistance by cholangiocarcinomas [4]. Hence, it is essential to explore alternative treatment options.

Enzyme prodrug therapy is an alternative approach for patients with different neoplastic diseases, wherein the enzyme can convert the non-toxic prodrug to a toxic anti-tumor drug in transfected tumors. In addition, in the “bystander effect”, toxic anti-tumor drugs can enter and kill surrounding tumor cells. Activating the systemic immune response after enzyme and prodrug treatment might further enhance the therapeutic effects [5].

The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/Ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) suicide gene system is a promising enzyme/prodrug system for various malignancies [6-8]. The main barrier inhibiting the wide clinical application of HSV-TK/GCV system is the low transfection and expression efficiency of systemically administered HSV-TK genes [5]. Image-guided interventional procedures for the direct delivery of high dose anti-tumor therapeutics to the target tumors could solve this problem.

Utilization of tissue- or cell-specific promoters is an ideal option to elevate the therapeutic effects of HSV-TK genes. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a set of chaperone proteins that function in the cytoprotection from denaturation or misfolding of cellular proteins corresponding to heat stress or temperature stimuli. HSPs are generally classified as small HSPs (such as HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90) and large HSPs according to their molecular weights [9]. HSPA6 (also known as HSP70B’) belongs to the HSP70 family. HSPA6 is a heat shock- and stress-inducible protein. The expression of HSPA6 is low under normal physiological conditions, with increased induction of protein synthesis in the presence of extreme temperatures [9,10]. The HSPA6 promoter plays a crucial role in this process. Thus, transferring this promoter upstream of an HSV-TK gene is beneficial, as it can elevate the HSV-TK gene expression level when the treated cells experience heat shock.

Recent studies have confirmed that image-guided interventional radiofrequency hyperthermia (RFH at approximately 42-45°C) can facilitate the effects of different anti-tumor treatments for a variety of carcinomas [11-14]. However, hyperthermia-enhanced therapy for cancer still has many drawbacks that include inadequate delivery systems for local heat administration and lack of efficient temperature monitoring.

In this study, we investigated the capability of a combination treatment by constructing an HSP promoter-mediated HSV-TK gene therapy system. We used an image-guided interventional procedure to deliver a high dose of HSP promoter-mediated HSV-TK genes to the tumors. Simultaneously, intratumoral RFH further enhance the HSV-TK gene therapeutic effects on cholangiocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

The present study consisted of two parts: (1) in vitro establishment of the “proof-of-principle” of RFH-enhanced lethality of the HSV-TK gene on human cholangiocarcinoma cells, and (2) in vivo feasibility of image-guided interventional RFH-enhanced direct intratumoral gene therapy of cholangiocarcinoma in mice.

In vitro experiments

Construction of the PHSP-TK/GFP-lentivirus

We successfully constructed the co-expressed lentiviral vectors of HSP-TK and green fluorescent protein (GFP) genes as published previously [15]. Since the same HSPA6 promoter simultaneously regulated the co-expression of PHSP-TK and GFP genes, the expression efficiency of PHSP-TK in transfected cholangiocarcinoma cells was detectable by measuring GFP signals using fluorescent microscopy.

Cell culture

Informed consent was provided from the human subjects to collect cells for experimentation. The experiment was approved by the institutional human ethics committee. Cholangiocarcinoma tissues were harvested from patients suffering from cholangiocarcinoma. The primary human cholangiocarcinoma cell line, ZJU-1125, was established using a single clone culture. The patient derived cholangiocarcinoma cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 × penicillin-streptomycin solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were cultured at 37°C in a thermostat incubator in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The ATCC provided the STR identification for our cholangiocarcinoma cells line ZJU-1125.

Detection of PHSP-TK gene transfection and expression

After cholangiocarcinoma cells were seeded into a 30-cm culture vessel for 24 h, the cells were incubated with PHSP-TK/lentivirus [multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 20] for 12 h. The culture medium was then replenished. HSV-TK gene expression at 72 h post-transfection was evaluated using flow cytometry analysis (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

RFH

Cholangiocarcinoma cells were cultivated in each chamber of a four-chamber cell culture slide (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA) at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well and incubated in a 37°C water bath. These cells were divided into four groups: gene transduction of PHSP-TK/GFP lentivirus plus RFH; RFH-only; PHSP-TK/GFP gene transduction-only; and untreated control. For gene transduction, PHSP-TK/lentivirus (MOI = 20 per chamber) was added to the cell-containing chambers for 48 h, followed by heating at 45°C for 20 min using the RFH system. For the RFH, a 0.032-inch radiofrequency heating wire was placed under the bottom of chamber number one of the four-chamber cell culture slide and then connected to a 2450 MHz RF generator (GMP150; OPTHOS, Rockville, MD, USA) to heat the slide at 45°C for 20 min. The temperature of the chambers was constantly monitored using a digital thermometer (Photon Control, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada). Forty-eight hours later, GCV was added to each cell culture chamber (10 μg/ml) for 48 h.

Cytotoxic and cell apoptosis assays

Cytotoxic and cell apoptosis assays were performed to evaluate the cell killing effects of PHSP-TK/GCV on cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was used to assess cell viability. Briefly, CCK-8 solution (100 μl) was dispensed in each chamber and incubated at 37°C for 2 h followed by measurement of the absorbance of each chamber at 450 nm using a Universal Microplate Reader (BIO-TEK Instruments, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Apoptosis was detected by staining with Annexin V and APC solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by flow cytometry analysis (BD Biosciences).

In vivo experiments

RFH-mediated gene therapy

The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Twenty-four 8-week-old BALB/c nude female mice (Slac laboratory animal center, Shanghai, China) were divided into four treatment groups (n = 6 per group): RFH+PHSP-TK/GFP; PHSP-TK/GFP-only; RFH-only; and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control. After human cholangiocarcinoma cells were transfected with PHSP-TK/GFP-lentivirus (MOI = 20) for 12 h, the residual medium was replaced with fresh culture medium, followed by analysis of HSV-TK-positive expression. HSV-TK-positive cells (5 × 106) were subcutaneously transplanted into the unilateral back of each mouse to create a human cholangiocarcinoma-bearing animal model. Two days after the transplantation of HSV-TK-positive cells, which was a sufficient time to allow HSV-TK expression, the 0.032-inch radiofrequency heating wire was inserted into the targeted tumors for local heating at 45°C for 20 min. A 2.7 mm micro-thermometry fiber was inserted into tumor parallel to the RF heating wire to instantly measure the temperature changes caused by RFH. Intraperitoneal GCV (25 mg/kg) was administered every 2 days for 14 days.

In-vivo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up

The treated animals were mechanically ventilated with 3% isoflurane mixed with 0.5 l/min oxygen during MRI follow-up. MRI was done using a 3.0-Tesla MR scanner (GE Healthcare Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) by placing the mouse into a 100 mm-diameter micro-imaging coil. T2-weighted images (T2WI) were acquired by rapid acquisition with the following OAx T2 FSE spin echo sequence: TR/TE = 2660/80 ms, field of view = 8 cm, matrix = 256 × 256, section thickness = 1.5 mm, intersection gap = 0.5 mm, NEX = 2, and total scan time = 1 min, 51 sec. MRI was performed on days 0, 7, and 14 after gene therapy.

MRI measurement of tumor volume

The tumor volume was measured using the Volume Rendering software on the GE workstation. Measurements were performed independently by two radiologists with 5 years-experience in the MRI diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. A region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn around the entire visible tumor. Once the ROIs were defined, the tumor volume was calculated automatically.

Histology confirmation

After achieving the satisfactory MR images, all tumor-bearing animals were sacrificed under anesthesia. The subcutaneous tumors were harvested. The volume (V) of each tumor was calculated using the formula: V = A × B2/2 (where A is the longer diameter and B is the shorter one). Due to the variation in tumor size, we used the relative tumor volume (RTV) to compare the tumor size changes, which was calculated as RTV = Vn/V0 (where Vn = tumor volume on day 7 or 14 post-treatment and V0 = tumor volume pre-treatment). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed to confirm the formation of cholangiocarcinoma. Terminal dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was used to examine cell apoptosis. The number of apoptotic cells was counted using Image J software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Statistical analyses

The significance of differences was evaluated using one-way ANOVA to compare in vitro gene expression levels, the efficacy of cytotoxicity, and apoptosis indices. Two-way ANOVA was performed to compare in vivo tumor sizes among different subject groups at three time points. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

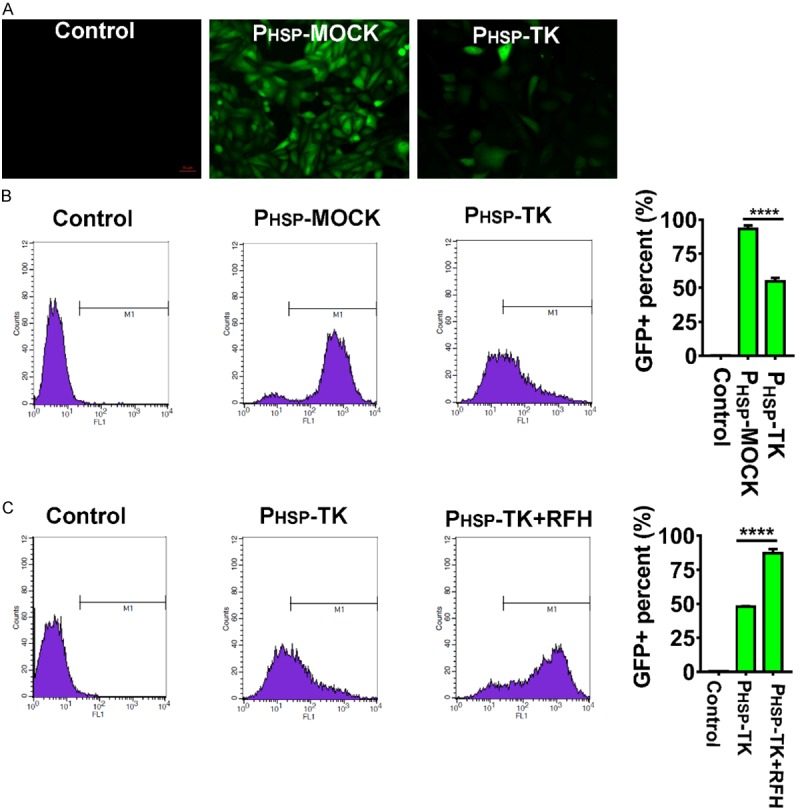

In vitro radiofrequency heating enhances PHSP-TK gene expression

After human cholangiocarcinoma cells were transfected with the PHSP-TK/GFP lentivirus, the percentage of GFP+ cells corresponded to the percentage of HSP-TK positive cells (Figure 1A). As compared to 94% GFP+ mock cells, only 55% of the cells were GFP+ after the cells were transfected with lentivirus containing the PHSP-TK gene (Figure 1B). However, the percentage of GFP+ cells rapidly increased from 47% to 89% after the cells were heated with RFH for 20 min at 45°C (Figure 1C). It indicated that HSP promoter was significantly activated due to the heat shock of RFH, more effective PHSP-TK gene expression were achieved.

Figure 1.

Radiofrequency hyperthermia (RFH) significantly enhances PHSP-TK gene expression in vitro (A) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of transfected human cholangiocarcinoma cells with PHSP-TK/GFP vector or mock vector demonstrates successful GFP expression (green color), which is confirmed by quantitative flow cytometry (B). (C) RFH significantly promotes the PHSP-TK gene expression level in transfected cells (89.08% vs 47.98), confirmed by flow cytometry.

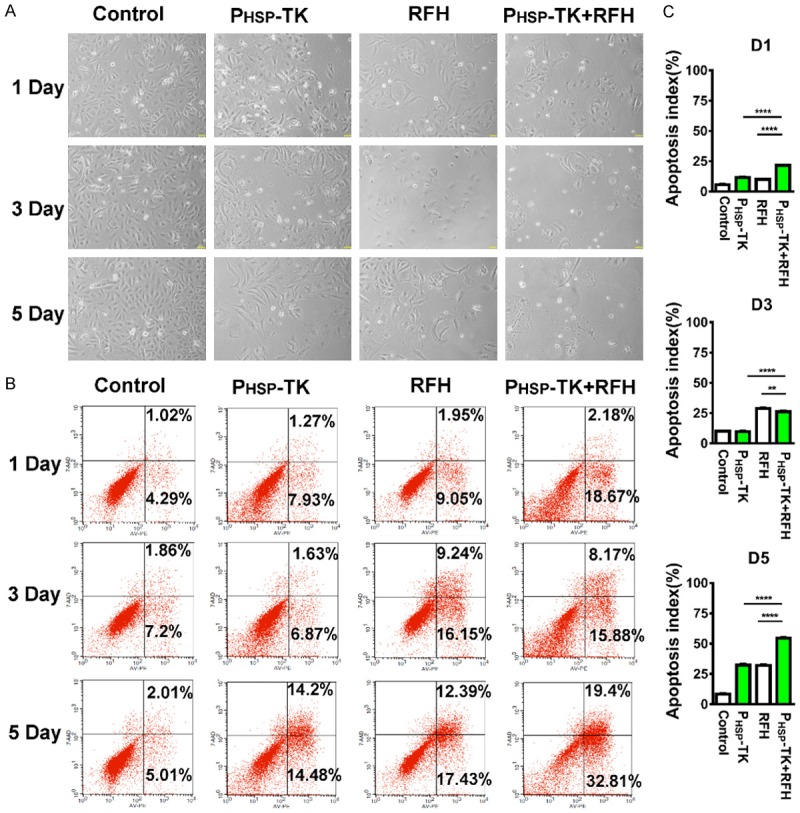

In vitro RFH significantly promotes cytotoxic effects of PHSP-TK gene therapy

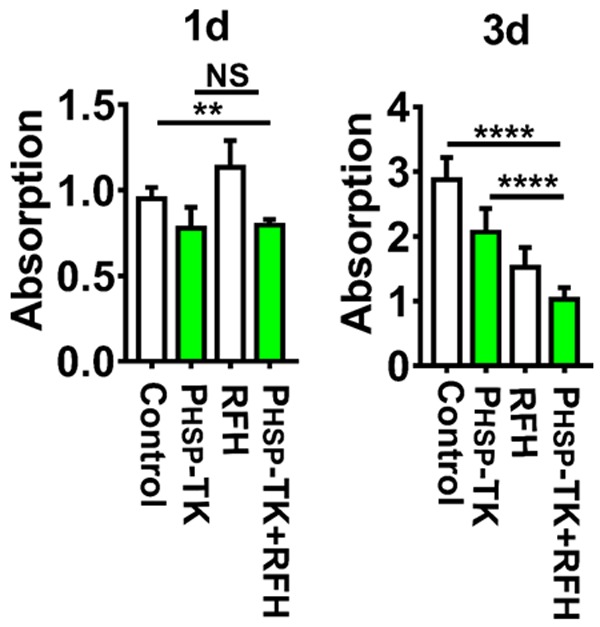

RFH resulted in a significant increase of apoptosis ratio combined with PHSP-TK gene therapy after the addition of GCV (10 μg/ml) (Figure 2A). The apoptosis index increased from 10 ± 0.14% in the HSP-TK treated group to 21.62 ± 0.17% in the PHSP-TK plus RFH group at day 1 (Figure 2B). As the time past, the apoptosis index of tumor cells increased. At day 5 after treatment with GCV, the tendency of cell death was more pronounced in the combination treatment compared to other control treatments (54.42 ± 0.65% vs 8.39 ± 0.23% for control, 32.34 ± 0.61% for PHSP-TK, and 31.98 ± 0.77% for RFH; Figure 2B, 2C). The CCK8 assay also indicated the stronger cytotoxic effects of the PHSP-TK plus RFH treatment in comparison with the PHSP-TK-only treatment. After GCV treatment for 3 consecutive days, the growth of the cholangiocarcinoma in PHSP-TK plus RFH group was more prominently inhibited compared to the cholangiocarcinoma in the PHSP-TK treatment group (Figure 3). It suggested that RFH significantly promoted the cell killing effects of PHSP-TK/GCV system on cholangiocarcinoma.

Figure 2.

Combined treatment using the PHSP-TK/GCV system plus RFH causes significant apoptosis in human cholangiocarcinoma cells in vitro (A) Light microscope assays in four different cell groups at day 5 after the treatments reveal decreased survival of cells by the combination treatment compared to other control cell groups, which is confirmed by subsequent quantitative flow cytometry analysis (B). (C) Apoptosis index of combinational treatment groups were significantly higher than those of other control groups. (** < 0.01, *** < 0.0001, **** < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity. The CCK8 assay at day 3 after the treatments demonstrates that the combined treatment using the PHSP-TK/GCV system plus RFH significantly inhibits the growth of human cholangiocarcinoma cells. ** < 0.01, **** < 0.0001.

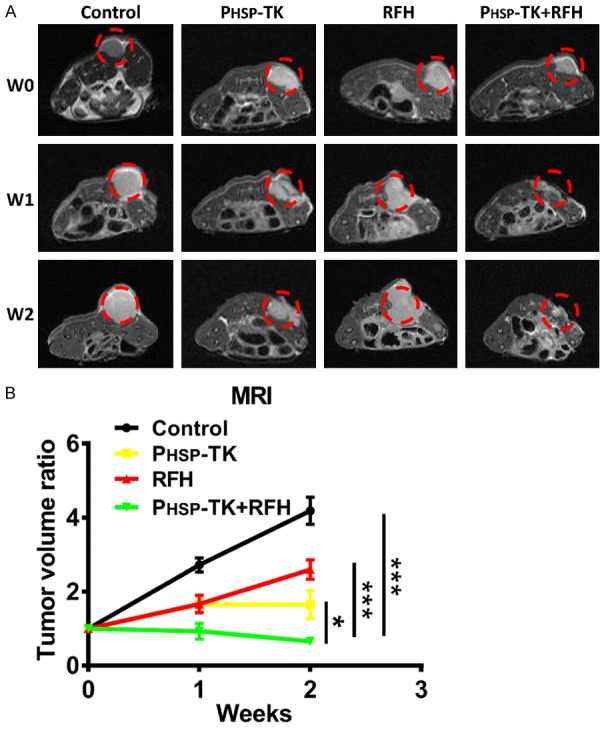

In vivo treatment of PHSP-TK plus RFH leads to significant reduction in the volume of cholangiocarcinoma

One week after the treatment, we found the combined therapy of PHSP-TK plus RFH significantly inhibited the tumor growth in the cholangiocarcinoma, as compared to other controlled treatments of RFH-only, PHSP-TK-only, or PBS treatment by using MRI evaluation. As the therapy continued, the difference between the PHSP-TK plus RFH group and other groups further increased. Two weeks after the treatments, the combinational treatment lead to the significant reduction of tumor volume, however the tumor volume increased in the other groups. It indicated that the only PHSP-TK plus RFH treatment had more powerful inhibitory effect on the growth of cholangiocarcinoma in vivo (Figure 4). These results showed that combinational treatment of PHSP-TK plus RFH might be the superior option compared to the RFH-only treatment, or PHSP-TK-only treatment in cholangiocarcinoma.

Figure 4.

In vivo follow-up MRI to monitor tumor size. Interventional RFH treatment significantly promotes the inhibitory effects of PHSP-TK/GCV therapy in cholangiocarcinoma bearing mice. A. The combined treatment with PHSP-TK gene therapy plus RFH reduces tumor volume compared to those with other control treatments within 2 consecutive weeks (w). B. Statistical analysis of MRI evaluation for the four different groups of mice, showing significantly decreased size with the combination therapy using PHSP-TK plus RFH at week 2 after the treatment, in comparison to other control treatments. * < 0.05, *** < 0.001.

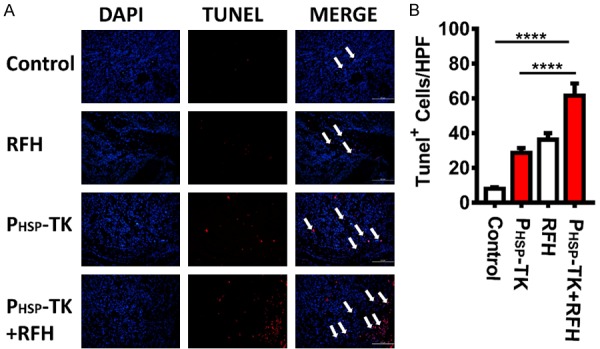

In vivo combinational approach of PHSP-TK plus RFH offered an effective treatment via promoting apoptosis of cholangiocarcinoma

Reversed fluorescence microscopy examination (Figure 5A) confirmed that the number of apoptosis cells of the PHSP-TK plus RFH group (61.6 ± 7.3) per high power field was significantly higher than that of the other treatment groups of control, RFH-only, or PHSP-TK-only (8 ± 0.9, 36.2 ± 3.9, 28.6 ± 3.0, respectively; P < 0.0001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.0001, respectively; Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

In vivo detection of apoptosis in cholangiocarcinomas using the TUNEL assay in the four different treatment groups. (A) Reverse fluorescence microscopy reveals a significant increase of apoptosis cells in PHSP-TK+RFH group compared to the other three control groups, (red dots), which is further confirmed by the TUNEL assay, **** < 0.0001 (B).

Discussion

The HSV-TK/GCV system is the most broadly utilized enzyme/prodrug in studies of suicide gene therapy [6,16,17]. Despite the abundant use of HSV-TK/GCV, low gene expression remains the main obstacle that limits the curative effects for suicide gene therapy [5]. To address this problem, tissue-specific promoters were used to elevate suicide gene expression levels [7,18,19]. HSP70B’ is a heat shock inducible protein. The heat shock element (HSE) in the HSP70B’ promoter plays an important role in response to heat shock [9,20]. We cloned the promoter of HSP70B’ upstream of the HSV-TK gene to construct a new suicide gene delivery system. The construct was activated by heat shock, resulting in significantly elevated HSV-TK gene expression levels, which produced sufficient toxic GCV triphosphate at the target tumors.

To further enhance HSV-TK/GCV efficacy, we also specifically developed a method using image-guided interventional RFH to create local and precise heating at the targeted tumors only [12,21], which allowed targeted heat shock in cholangiocarcinoma cells. The innovative integration of image-guided interventional RFH with the HSP promoter-mediated HSV-TK gene therapeutic system permitted the confirmation that RFH at approximately 45°C significantly enhanced HSV-TK gene expression and cytotoxic effects on cholangiocarcinoma cells.

Concurrent with the experimental results in vitro, the tumor volume of the combinational therapy group shrank more significantly as compared to those of RFH-only group, PHSP-TK-only group or saline group in vivo in cholangiocarcinoma bearing mice. The synergistic effects of HSV-TK gene therapy and RFH indicate that the HSP promoter-mediated suicide gene therapy combined with RFH is a promising approach to the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.

Image-guided anti-tumor therapies avoid various drawbacks of systemic therapeutic administration, which include lethal effects on normal cells, low therapeutic dose at the targets, and toxic damages to other vital organs due to systemic administration [22]. The interventional procedure enables the precise transport of therapeutic genes to the targets, while interventional RFH further contributes to the targeted heating of selected areas. These potent synergistic effects improved the therapeutic efficacy of cholangiocarcinoma in the current study.

The measurement of tumor volume is an important assessor of the clinical stage and disease outcomes of cancer [23,24]. We evaluated tumor volumes using MRI and demonstrated that intratumoral RFH significantly promoted the direct therapeutic effects of HSV-TK gene therapy throughout the therapeutic process.

To conclude, image-guided interventional RFH significantly enhanced the HSP promoter-mediated HSV-TK gene therapeutic efficacy for cholangiocarcinoma. The new combinational treatment can eliminate multiple obstacles of systemic HSV-TK gene therapy, which include low gene transfection and expression, and killing of normal cells due to less precise gene administration. The novel technique may open new avenues for image-guided combinational therapy of cholangiocarcinoma via the innovative integration of image-guided delivery of high-dose therapeutic genes with the simultaneous generation of local RFH at the targets, which further enhances HSP promoter-mediated direct HSV-TK gene therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81430040 and 81571738), NIH RO1 grant EBO12467, medical scientific research foundation of Zhejiang Province of china (Grant No. 2017KY394), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province of China (No. Y18H180007) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma-evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:95–111. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383:2168–2179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth EC, Babina IS, Turner NC. Gatekeeper mutations and intratumoral heterogeneity in FGFR2-translocated cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:248–249. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karjoo Z, Chen X, Hatefi A. Progress and problems with the use of suicide genes for targeted cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;99:113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mooney R, Abdul Majid A, Batalla J, Annala AJ, Aboody KS. Cell-mediated enzyme prodrug cancer therapies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;118:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo WY, Hwu L, Wu CY, Lee JS, Chang CW, Liu RS. STAT3/NF-kappaB-regulated lentiviral TK/GCV suicide gene therapy for cisplatin-resistant triple-negative breast cancer. Theranostics. 2017;7:647–663. doi: 10.7150/thno.16827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leinonen HM, Ruotsalainen AK, Maatta AM, Laitinen HM, Kuosmanen SM, Kansanen E, Pikkarainen JT, Lappalainen JP, Samaranayake H, Lesch HP, Kaikkonen MU, Yla-Herttuala S, Levonen AL. Oxidative stress-regulated lentiviral TK/GCV gene therapy for lung cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6227–6235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Liu T, Rios Z, Mei Q, Lin X, Cao S. Heat shock proteins and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:226–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Pastor R, Burchfiel ET, Thiele DJ. Regulation of heat shock transcription factors and their roles in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:4–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devun F, Biau J, Huerre M, Croset A, Sun JS, Denys A, Dutreix M. Colorectal cancer metastasis: the DNA repair inhibitor Dbait increases sensitivity to hyperthermia and improves efficacy of radiofrequency ablation. Radiology. 2014;270:736–746. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Zhang F, Bai Z, Wang J, Qiu L, Li Y, Meng Y, Valji K, Yang X. Orthotopic esophageal cancers: intraesophageal hyperthermia-enhanced direct chemotherapy in rats. Radiology. 2017;282:103–112. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y, Han G, Wang Y, Hu X, Li Z, Chen L, Bai W, Luo J, Zhang Y, Sun J, Yang X. Radiofrequency heat-enhanced chemotherapy for breast cancer: towards interventional molecular image-guided chemotherapy. Theranostics. 2014;4:1145–1152. doi: 10.7150/thno.10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F, Le T, Wu X, Wang H, Zhang T, Meng Y, Wei B, Soriano SS, Willis P, Kolokythas O, Yang X. Intrabiliary RF heat-enhanced local chemotherapy of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line: monitoring with dual-modality imaging--preclinical study. Radiology. 2014;270:400–408. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo J, Wu X, Zhou F, Zhou Y, Huang T, Liu F, Han G, Chen L, Bai W, Wu X, Sun J, Yang X. Radiofrequency hyperthermia promotes the therapeutic effects on chemotherapeutic-resistant breast cancer when combined with heat shock protein promoter-controlled HSV-TK gene therapy: toward imaging-guided interventional gene therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:65042–65051. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen ZH, Yu YP, Zuo ZH, Nelson JB, Michalopoulos GK, Monga S, Liu S, Tseng G, Luo JH. Targeting genomic rearrangements in tumor cells through Cas9-mediated insertion of a suicide gene. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mircetic J, Dietrich A, Paszkowski-Rogacz M, Krause M, Buchholz F. Development of a genetic sensor that eliminates p53 deficient cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1463. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01688-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ide K, Mitsui K, Irie R, Matsushita Y, Ijichi N, Toyodome S, Kosai KI. A novel construction of lentiviral vectors for eliminating tumorigenic cells from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2018;36:230–239. doi: 10.1002/stem.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YH, Kim KT, Lee SJ, Hong SH, Moon JY, Yoon EK, Kim S, Kim EO, Kang SH, Kim SK, Choi SI, Goh SH, Kim D, Lee SW, Ju MH, Jeong JS, Kim IH. Image-aided suicide gene therapy utilizing multifunctional hTERT-targeting adenovirus for clinical translation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2016;6:357–368. doi: 10.7150/thno.13621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mashaghi A, Bezrukavnikov S, Minde DP, Wentink AS, Kityk R, Zachmann-Brand B, Mayer MP, Kramer G, Bukau B, Tans SJ. Alternative modes of client binding enable functional plasticity of Hsp70. Nature. 2016;539:448–451. doi: 10.1038/nature20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velez E, Goldberg SN, Kumar G, Wang Y, Gourevitch S, Sosna J, Moon T, Brace CL, Ahmed M. Hepatic thermal ablation: effect of device and heating parameters on local tissue reactions and distant tumor growth. Radiology. 2016;281:782–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adam A, Kenny LM. Interventional oncology in multidisciplinary cancer treatment in the 21(st) century. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:105–113. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker WP, Cheville JC, Frank I, Zaid HB, Lohse CM, Boorjian SA, Leibovich BC, Thompson RH. Application of the stage, size, grade, and necrosis (SSIGN) score for clear cell renal cell carcinoma in contemporary patients. Eur Urol. 2017;71:665–673. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD, Rusch VW. Lung cancer - major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:138–155. doi: 10.3322/caac.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]