Abstract

Adverse drug reactions can cause considerable discomfort. They can be life-threatening in severe cases, requiring or prolonging hospitalization, impeding proper treatment, and increasing treatment costs considerably. Although the incidence of severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) is low, they can be serious, have permanent sequelae, or lead to death. A recent pharmacogenomic study confirmed that genetic factors can predispose an individual to SCARs. Genetic markers enable not only elucidation of the pathogenesis of SCARs, but also screening of susceptible subjects. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes associated with SCARs include HLA-B*57:01 for abacavir (Caucasians), HLA-B*58:01 for allopurinol (Asians), HLA-B*15:02 (Han Chinese) and HLA-A*31:01 (Europeans and Koreans) for carbamazepine, HLA-B*59:01 for methazolamide (Koreans and Japanese), and HLA-B*13:01 for dapsone (Asians). Therefore, prescreening genetic testing could prevent severe drug hypersensitivity reactions. Large-scale epidemiologic studies are required to demonstrate the usefulness and cost-effectiveness of screening tests because their efficacy is affected by the genetic differences among ethnicities.

Keywords: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Drug hypersensitivity syndrome, Pharmacogenetics, HLA antigens

INTRODUCTION

Adverse reactions caused by drugs occur frequently. They can be life-threatening in severe cases, requiring or prolonging hospitalization, impeding proper treatment, and increasing treatment costs considerably [1]. Lazarou et al. [2] conducted a meta-analysis of 39 studies conducted in the United States from 1966 to 1999 and found that 15.1% of hospitalized patients experienced adverse drug reactions and 6.7% serious adverse reactions. Indeed, 3.1% to 6.2% of all hospitalized patients were admitted due to adverse drug reactions [2].

Skin manifestations are the most common clinical manifestations of adverse drug reactions and range from immediate hypersensitivity reactions, such as urticaria and angioedema, to delayed hypersensitivity reactions such as maculopapular eruption, erythema multiforme, and fixed drug eruption. Although the majority of patients who experience such reactions recover spontaneously with drug withdrawal, some may develop life-threatening severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DISH)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) [3]. The annual incidence of SCARs is reportedly 3 to 5/1,000,000 persons [4,5]. Despite this low incidence, complications such as infection due to skin exfoliation or systemic organ impairment can result in death. The mortality rate is 10% for SJS, 30% for SJS/TEN overlap, 50% for TEN, and 5% for DRESS [6]. SCARs may permanently damage the affected mucosa or skin. Among survivors of SJS/TEN, 50% have severe sequelae, including symblepharon, corneal scarring leading to visual impairment, perineal stricture, bronchiolitis, hair loss, and scarring [7].

Overlap hypersensitivity syndrome is an important emerging concept that suggests that SCAR lesions overlap with another condition. In fact, 20% of all drug eruptions reportedly exhibit an overlap; the most common is DISH with TEN-like features. Thus, SCARs may represent a clinical spectrum of reactions with common pathophysiologic mechanisms.

A recent pharmacogenomic study demonstrated that certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes can induce T-cell activation to a specific drug, resulting in an immune response. Specific HLA genotypes play an important role in the development of SCARs [8]. In 1987, Roujeau et al. [9] reported that HLA-A29, HLA-B12, and HLA-DR7 were associated with sulfonamide‑induced TEN, and HLA-A2 and HLA-B12 were associated with oxicam‑induced TEN in a European population. They hypothesized that the HLA genotype is a major factor in the development of SJS/TEN [9]. The occurrence of SCARs to some drugs is reportedly strongly associated with specific HLA alleles [10]. In addition, the HLA genotype is useful for identifying patients at high risk of SCARs to certain drugs. However, results derived from one ethnicity may not be applicable to others, where the association between SCARs and HLA genotype differs by ethnicity.

In addition to HLA, the T-cell receptor (TCR) plays an important role in the development of SCARs. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in response to carbamazepine that highly restrict V-α and V-β TCR repertoires have been found in patients with, but not in those without, carbamazepine hypersensitivity [11]. Although not yet clinically useful, combining functional screening of TCR repertoires with HLA haplotype screening prior to drug administration has been suggested.

ABACAVIR AND NEVIRAPINE

The first report of a drug-induced SCAR-HLA association was between HLA-B*57:01 and abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS). Abacavir is a nucleoside analogue used to treat acquired immune deficiency syndrome. It causes delayed systemic hypersensitivity reactions, such as fever and skin rash, in 5% to 8% of patients after 1 to 6 weeks of use [12]. AHS can manifest systemic hypersensitivity reactions including fever, rash, gastrointestinal symptoms, and respiratory symptoms; this is similar to DRESS syndrome. Numerous fatal cases of AHS have been reported [12].

Following the report of Hetherington et al. [13] in 2002, Mallal et al. [14] used a candidate gene approach to confirm the association between abacavir hypersensitivity and HLA allele in a Western Australian human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cohort; HLA-B*57:01 was strongly correlated with hypersensitivity to abacavir (odds ratio [OR], 117). Later, a prospective randomized double‑blind clinical trial confirmed the usefulness of pre‑treatment HLA-B*57:01 allele screening for preventing abacavir‑induced hypersensitivity reactions (the Prospective Randomized Evaluation of DNA Screening in a Clinical Trial [PREDICT-1] study) [12]. In that study, abacavir was not prescribed to patients with HLA-B*57:01, which reduced the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions from 7.8% to 3.4%. Furthermore, the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions confirmed by patch test decreased from 2.7% to 0.0% [12]. Accordingly, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends HLA-B*57:01 screening before abacavir treatment [12]. An association of HLA-B*57:01 with hypersensitivity to abacavir has been observed in Caucasians, but not in African-Americans [15]. However, HLA-B*57:01 reportedly has a 100% negative predictive value for abacavir‑induced hypersensitivity reactions in Caucasians and African-Americans (The Study of Hypersensitivity to Abacavir and Pharmacogenetic Evaluation [SHAPE] study) [16].

The allele frequency of HLA-B*57:01 is low in Koreans (0.2%) [17] and Japanese (0.005%) [18]. Thus, confirming the association of HLA-B*57:01 with hypersensitivity to abacavir in non-Caucasian ethnicities is problematic because the HLA-B*57:01 test for abacavir hypersensitivity is not clinically relevant in Koreans [19] or Japanese [20]. The anti-HIV agent nevirapine also causes hypersensitivity reactions. Interestingly, the HLA alleles associated with hypersensitivity reactions to nevirapine also differ by ethnicity [21]. In Thailand, hypersensitivity to nevirapine is associated with HLA-B*35:05 and prospective studies are currently underway to confirm the clinical utility of HLA-B*35:05 screening [22]. Nevirapine‑induced DRESS is reportedly associated with HLADRB1*01:01 in Caucasians [23] and HLA-Cw8 in Japanese [24].

CARBAMAZEPINE AND OTHER AROMATIC ANTIEPILEPTICS

Carbamazepine is widely used to control convulsive disease and pain. In 2004, it was reported that in a Han Chinese population, 100% of carbamazepine‑induced SJS patients were positive for the HLA-B*15:02 allele, compared to 3% of tolerant patients (OR, 2,504) [25]. Therefore, SCAR could be prevented by administering a customized treatment to patients with HLA-B*15:02.

In 2011, Chen et al. [26] screened for persons in Taiwan with HLA-B*15:02 to whom carbamazepine was not prescribed. This reduced the incidence of carbamazepine-induced SJS/TEN from 0.23% to 0%; moreover, the decrease in medical costs due to prevention of SJS/TEN was greater than the cost of the screening [26,27]. The usefulness of genetic screening has been demonstrated by confirming the significant preventive effect of the HLA-B*15:02 test [26]. Therefore, the US and Taiwanese FDAs recommend HLA-B*15:02 testing prior to prescribing carbamazepine to Asians, particularly Southeast Asians [28,29].

The genetic association of carbamazepine hypersensitivity is ethnicity-specific. The strong association between carbamazepine‑induced SJS/TEN and HLA-B*15:02 was not observed in Caucasians [30], Japanese [31], or Indians [32], who have a lower frequency of HLA-B*15:02 than Han Chinese in Hong Kong [33] or the general populations of Thailand [34] and Malaysia [35]. Thus, the HLA distribution in the ethnicity of interest should be considered when assessing the correlation between specific HLA types and drug‑induced SCARs [36]. More than 15% of the population of Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia, and parts of the Philippines are positive for HLA-B*15:02, compared to 10% in Taiwan; 2% to 4% in South Asia, including India; and < 1% in Korea and Japan [18].

The association of carbamazepine‑induced SCARs with HLA has been investigated in genome‑wide association studies (GWASs) in Japan and the United Kingdom [37,38]. HLA-A*31:01 is strongly associated with carbamazepine‑induced DRESS but weakly associated with carbamazepine‑induced SJS/TEN in Europeans [38]. In Japanese, HLA-A*31:01 is strongly associated with carbamazepine‑induced DIHS and SJS/TEN [37]. In Malaysia, HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 are associated with carbamazepine‑induced SJS/TEN [39]. Thus, the association between carbamazepine‑induced SCARs and HLA type differs by ethnicity. HLA-B*15:02 is very rare in Koreans, and so no significant correlation with SCARs has been reported. HLA-B*15:11 (OR, 18.0) and HLA-A*31:01 (OR, 8.8) are associated with carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in Koreans; however, the correlation was of insufficient strength for application to screening (Table 1) [40].

Table 1.

Summary of reports on the association of HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 with carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions

| HLA | Ethnicity | Phenotypes | Patients, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B*15:02 | Han Chinese [25] | SJS/TEN | 44 (100) | 3/101 (3) | 3.13 × 10–27 | 2,504 (126–49,522) |

| Thai [34] | SJS/TEN | 37/42 (88.1) | 10/84 (11.9) | 2.89 × 10–12 | 54.76 (14.62–205.13) | |

| Korean [40] | SJS/TEN | 1/7 (14.3) | 0/50 (0) | NS | 23.3 (0.9–634.0) | |

| A*31:01 | European [38] | DRESS | 10/27 (37.0) | 10/257 (3.9) | 0.03 | 12.41 (1.27–121.03) |

| Japanese [37] | SJS/TEN/DIHS | 37/61 (60.7) | 47/376 (12.5) | 3.64 × 10–15 | 10.8 (5.9–19.6) | |

| Korean [40] | HSS | 10/17 (58.8) | 7/50 (14.0) | 0.001 | 8.8 (2.5–30.7) |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SJS, Stevens-Johnsons syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; NS, not significant; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; DIHS, drug induced hypersensitivity syndrome; HSS, hypersensitivity syndrome.

Several studies have evaluated other aromatic antiepileptics. In a Han Chinese population, HLA-B*15:02 was significantly associated with phenytoin‑induced SJS/TEN (OR, 5.1) and oxcarbazepine-induced SJS (OR, 80.7). In addition, the HLA-A*02:01/C*15:02 combination is reportedly related to phenytoin‑induced SJS/TEN and HLA-A*24:02 with phenytoin‑induced DRESS (OR, 22.56) [41]. In contrast, lamotrigine was not associated with HLA-B*15:02 [41]. In a Spanish population, HLA-B*38:01 was associated with lamotrigine‑induced SJS/TEN (OR, 147.0) and HLA‑A*24:02 with lamotrigine‑induced DRESS (OR, 23.5) [42]. In Europeans, HLA‑B*15:02 was not correlated with lamotrigine‑induced SCARs, while HLA-B*58:01, A*68:01, C*07:18, DQB1*06:09, and DRB1*13:01 showed weak associations [43]. In Koreans, HLA-A*31:01 was associated with lamotrigine‑induced SCARs (OR, 11.43) [44].

In a recent study involving a Thai population, lamotrigine‑induced maculopapular eruption was associated with HLA-A*33:03, HLA-B*15:02, and HLA-B*44:03 [45]. However, no HLA was significantly associated with SCARs [45]. In Koreans, lamotrigine-induced maculopapular eruption was associated with the coexistence of HLA-A*24:02 and C*01:02 [46].

ALLOPURINOL

Allopurinol, a uric-acid lowering agent used to treat gout, has long been prescribed in clinical practice. However, allopurinol has been criticized as a cause of SJS, TEN, and DRESS. In 2005, HLA-B*58:01 was found to be strongly associated with allopurinol‑induced SCARs in a case‑control study of a Han Chinese population in Taiwan (OR, 580.3) [47,48]. In Koreans, HLA-B*58:01 was strongly associated with allopurinol‑induced SCARs (OR, 97.8) [49]. Among European and Japanese patients with allopurinol‑induced SCARs, 70% and 40%, respectively, were positive for HLA-B*58:01 [31,50,51]. Considering its very low frequency in Europeans and Japanese, this finding supports the importance of HLA-B*58:01 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of reports on the association of HLA-B*58:01 and allopurinol-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions

| Ethnicity | Phenotypes | Patients, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han Chinese [47] | SJS/TEN | 51/51 (100) | 20/135 (15.0) | 4.7 × 10–24 | 580.3 (34.4–9,780.9) |

| European [50] | SJS/TEN | 14/27 (55) | 28/1822 (1.5) | < 1.0 × 10–6 | 80 (34–187) |

| Japanese [31] | SJS/TEN | 2/10 (20) | 6/986 (0.61) | < 1.0 × 10–4 | 40.83 (10.5–158.9) |

| Thai [48] | SJS/TEN | 27/27 (100) | 7/54 (13.0) | 1.6 × 10–13 | 348.3 (19.2–6,336.9) |

| Korean [49] | SJS/TEN, DRESS | 23/25 (92.0) | 6/57 (10.5) | 2.45 × 10–11 | 97.8 (18.3–521.5) |

| Portuguese [51] | SJS/TEN, DRESS | 16/25 (64) | 1/23 (4) | 5.9 × 10–9 | 39.11 (4.49–340.51) |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SJS, Stevens-Johnsons syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

Thus, HLA-B*58:01 is associated with allopurinol‑induced SCARs. However, some HLA-B*58:01 carriers do not develop SCARs after taking allopurinol. In a retrospective cohort analysis of allopurinol‑treated patients with chronic renal insufficiency in Korea, SCARs occurred in only 18% of patients with HLA-B58 [52]. All Koreans have the HLA-B*58:01 serotype of HLA-B58 [17].

Although an 18% incidence is very high considering the extreme rarity of SCARs, 82% of HLA-B*58:01 carriers with chronic renal insufficiency, an important risk factor for SCARs, did not have SCARs despite long‑term administration of allopurinol. This suggests that other risk factors are associated with allopurinol hypersensitivity reactions. In a retrospective cohort study of allopurinol-treated Korean patients, the frequency of HLA-A*02:01 was significantly lower in SCAR than in non‑SCAR patients, suggesting that HLA-A*02:01 protects against SCARs [49].

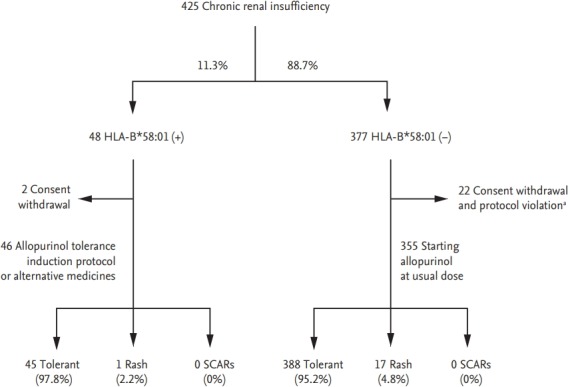

In a retrospective cohort study, HLA-B*58:01-negative patients did not develop SCARs, suggesting that HLA-B*58:01 could be a useful marker for personalized treatments [49]. In Korea, a prospective study assessed the induction of allopurinol tolerance through desensitization or administration of an alternative medication to HLA-B*58:01 carriers. The incidence of SCARs was reduced to 0%, compared to 18% in historical controls (Fig. 1) [53]. Similarly, in Taiwan, HLA-B*58:01 screening was performed prior to allopurinol administration and the use of allopurinol was prohibited in HLA-B*58:01 patients [54]; this reduced the incidence of allopurinol SCARs in HLA-B*58:01 patients to 0% [54].

Figure 1.

Allopurinol was administered according to a tolerance induction protocol or substituted for an alternative medication in 46 patients with the HLA-B*58:01 allele. During the 90-day period of drug administration, none of 46 patients with the HLA-B*58:01 allele developed severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCARs). Adapted from Jung et al., with permission from Springer Nature [50]. HLA, human leukocyte antigen. a Withdrawal of allopurinol regardless of hypersensitivity.

METHAZOLAMIDE AND OTHER CARBONIC ANHYDRASE INHIBITORS

Methazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor used as an intraocular pressure-lowering drug for treatment of glaucoma and other ophthalmic diseases. All methazolamide-induced SCARs were SJS/TEN. Methazolamide-induced SJS was first reported in two Japanese-Americans in 1995. In 1997, and three of four Japanese patients with methazolamide-induced SJS had HLA-B59 [55]. This was replicated in Koreans and suggests an association of methazolamide‑induced SJS with HLA‑B59. Indeed, all Korean patients with methazolamide‑induced SJS/TEN with available HLA data had HLA-B59 serotypes [56]. HLA-B*59:01 is the only HLA-B59 subtype detected in Koreans [17]. In 2011, high-resolution HLA genotyping of HLA class I alleles was performed in five Korean patients with methazolamide-induced SJS/TEN; all had HLA-B*59:01 and HLA-C*01:02 [56]. In 2010, the risk of methazolamide‑induced SJS/TEN in patients with HLA-B*59:01 was found to be significantly higher (OR, 249.8) than that in the general population [56]. Thereafter, four cases of methazolamide‑induced SJS/TEN in Korea were reported, all of which had the HLA-B*59:01 allele [57]. In China, seven of eight Han Chinese patients with methazolamide-induced SJS/TEN had the HLA-B*59:01 allele (OR, 305.0) [58]. Two further HLA-B*59:01-positive Chinese patients with methazolamide-induced TEN have been reported recently [59,60]. The HLA-B*59:01 allele is present in 1% to 2% and < 0.5% of the general populations of Korea and Japan, and China, respectively, but is extremely rare in Caucasians and African-Americans [18]. Interestingly, methazolamide‑related SCARs have to date been reported only in Koreans, Japanese, and Chinese. Several cases of SJS/TEN are related to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors other than methazolamide; e.g., acetazolamide, dorzolamide, and brinzolamide [56]. HLA typing has been performed in only one case of acetazolamide‑induced SCAR; HLA-B59 was identified [61]. This suggests that SCARs to similar classes of drugs have similar associations with HLA-B*59:01 [61]. Further studies are needed to confirm this.

DAPSONE

Dapsone is an antimicrobial agent used to treat leprosy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. It also possesses anti‑inflammatory activity and so is used against certain immunologic diseases. Similar to DRESS, dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome has an incidence of 1.4% [62]. HLA-B*13:01 was associated with dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome in Chinese patients (OR, 20.5) [63]. HLA-B*13:01 is more common in Asians than in Europeans and Africans; the frequency of HLA-B*13:01 is 1% to 20% in Chinese, 2.1% in Koreans, 1.5% in Japanese, and 1% to 12% in Indians [63]. In contrast, HLA-B*13:01 is extremely rare in Europeans and Africans [63]. All SCARs related to dapsone were DRESS; no case of dapsone-related SJS/TEN has been reported to date.

NON-HLA GENE ASSOCIATION STUDIES

Most of the genes associated with SCAR identified to date are HLAs, mainly class I. However, some genes involved in drug metabolism may be involved in the development, recovery, and prognosis of SCAR. A potential association between mutations in the cytochrome P gene with phenytoin‑induced SCAR has been reported, particularly in patients with the CYP2C9*3 mutation, which is associated with phenytoin‑induced SCARs [64]. In addition, the CYP2B6 G516T and T983C single‑nucleotide polymorphisms are reportedly associated with nevirapine-induced SJS/TEN [65].

CONCLUSIONS

Genome studies of adverse drug reactions will be accelerated by novel genetic techniques, such as GWAS and next-generation sequencing, as well as by existing candidate gene approaches. Future pharmacogenomic studies will identify more candidate genetic markers, which will enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions and facilitate identification of high-risk patients. However, the clinical usefulness of HLA screening to prevent SCARs is dependent on the frequency of the HLA type in the ethnicity of interest and the cost of alternative drugs. Therefore, clinical application of HLA should be assessed taking into consideration various conditions. Large-scale epidemiologic studies should evaluate the usefulness and cost-effectiveness of such screening, as are efforts to identify other HLA types associated with SCARs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety to the regional pharmacovigilance center in 2018.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eichelbaum M, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Evans WE. Pharmacogenomics and individualized drug therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:119–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roujeau JC. Clinical heterogeneity of drug hypersensitivity. Toxicology. 2005;209:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mockenhaupt M, Schopf E. Epidemiology of drug-induced severe skin reactions. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996;15:236–243. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strom BL, Carson JL, Halpern AC, et al. A population-based study of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Incidence and antecedent drug exposures. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mockenhaupt M. The current understanding of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:803–813. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roujeau JC. Immune mechanisms in drug allergy. Allergol Int. 2006;55:27–33. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roujeau JC, Huynh TN, Bracq C, Guillaume JC, Revuz J, Touraine R. Genetic susceptibility to toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1171–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung WH, Hung SI, Chen YT. Human leukocyte antigens and drug hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:317–323. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282370c5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko TM, Chung WH, Wei CY, et al. Shared and restricted T-cell receptor use is crucial for carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hetherington S, Hughes AR, Mosteller M, et al. Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:1121–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallal S, Nolan D, Witt C, et al. Association between presence of HLA-B*5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:727–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes AR, Mosteller M, Bansal AT, et al. Association of genetic variations in HLA-B region with hypersensitivity to abacavir in some, but not all, populations. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:203–211. doi: 10.1517/phgs.5.2.203.27481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saag M, Balu R, Phillips E, et al. High sensitivity of human leukocyte antigen-b*5701 as a marker for immunologically confirmed abacavir hypersensitivity in white and black patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1111–1118. doi: 10.1086/529382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KW, Oh DH, Lee C, Yang SY. Allelic and haplotypic diversity of HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 genes in the Korean population. Tissue Antigens. 2005;65:437–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HJ, Park JW, Yang MS, et al. Re-exposure to low osmolar iodinated contrast media in patients with prior moderate-to-severe hypersensitivity reactions: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:2886–2893. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4682-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park WB, Choe PG, Song KH, et al. Should HLA-B*5701 screening be performed in every ethnic group before starting abacavir? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:365–367. doi: 10.1086/595890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatanaga H, Honda H, Oka S. Pharmacogenetic information derived from analysis of HLA alleles. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:207–214. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips EJ, Chung WH, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau JC, Mallal SA. Drug hypersensitivity: pharmacogenetics and clinical syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3 Suppl):S60–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chantarangsu S, Mushiroda T, Mahasirimongkol S, et al. HLA-B*3505 allele is a strong predictor for nevirapine-induced skin adverse drug reactions in HIV-infected Thai patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:139–146. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32831d0faf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin AM, Nolan D, James I, et al. Predisposition to nevirapine hypersensitivity associated with HLA-DRB1*0101 and abrogated by low CD4 T-cell counts. AIDS. 2005;19:97–99. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501030-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gatanaga H, Yazaki H, Tanuma J, et al. HLA-Cw8 primarily associated with hypersensitivity to nevirapine. AIDS. 2007;21:264–265. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801199d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004;428:486. doi: 10.1038/428486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen P, Lin JJ, Lu CS, et al. Carbamazepine-induced toxic effects and HLA-B*1502 screening in Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1126–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong D, Sung C, Finkelstein EA. Cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*1502 genotyping in adult patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy in Singapore. Neurology. 2012;79:1259–1267. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826aac73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuehn BM. FDA: epilepsy drugs may carry skin risks for Asians. JAMA. 2008;300:2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrell PB, Jr, McLeod HL. Carbamazepine, HLA-B*1502 and risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: US FDA recommendations. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1543–1546. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lonjou C, Thomas L, Borot N, et al. A marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome ...: ethnicity matters. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:265–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Aihara M, et al. HLA-B locus in Japanese patients with anti-epileptics and allopurinol-related Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1617–1622. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.11.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devi K. The association of HLA B*15:02 allele and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by aromatic anticonvulsant drugs in a South Indian population. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:70–73. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Man CB, Kwan P, Baum L, et al. Association between HLA-B*1502 allele and antiepileptic drug-induced cutaneous reactions in Han Chinese. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1015–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tassaneeyakul W, Tiamkao S, Jantararoungtong T, et al. Association between HLA-B*1502 and carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a Thai population. Epilepsia. 2010;51:926–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Then SM, Rani ZZ, Raymond AA, Ratnaningrum S, Jamal R. Frequency of the HLA-B*1502 allele contributing to carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions in a cohort of Malaysian epilepsy patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yip VL, Marson AG, Jorgensen AL, Pirmohamed M, Alfirevic A. HLA genotype and carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:757–765. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozeki T, Mushiroda T, Yowang A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies HLA-A*3101 allele as a genetic risk factor for carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1034–1041. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCormack M, Alfirevic A, Bourgeois S, et al. HLA-A*3101 and carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions in Europeans. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1134–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khor AH, Lim KS, Tan CT, et al. HLA-A*31: 01 and HLA-B*15:02 association with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis to carbamazepine in a multiethnic Malaysian population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27:275–278. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SH, Lee KW, Song WJ, et al. Carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions and HLA genotypes in Koreans. Epilepsy Res. 2011;97:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liu ZS, et al. Common risk allele in aromatic antiepileptic-drug induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Han Chinese. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:349–356. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramirez E, Bellon T, Tong HY, et al. Significant HLA class I type associations with aromatic antiepileptic drug (AED)-induced SJS/TEN are different from those found for the same AED-induced DRESS in the Spanish population. Pharmacol Res. 2017;115:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazeem GR, Cox C, Aponte J, et al. High-resolution HLA genotyping and severe cutaneous adverse reactions in lamotrigine-treated patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:661–665. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32832c347d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim BK, Jung JW, Kim TB, et al. HLA-A*31:01 and lamotrigine-induced severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a Korean population. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:629–630. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koomdee N, Pratoomwun J, Jantararoungtong T, et al. Association of HLA-A and HLA-B alleles with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the Thai population. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:879. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moon J, Park HK, Chu K, et al. The HLA-A*2402/Cw*0102 haplotype is associated with lamotrigine-induced maculopapular eruption in the Korean population. Epilepsia. 2015;56:e161. doi: 10.1111/epi.13087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tassaneeyakul W, Jantararoungtong T, Chen P, et al. Strong association between HLA-B*5801 and allopurinol-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a Thai population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:704–709. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328330a3b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang HR, Jee YK, Kim YS, et al. Positive and negative associations of HLA class I alleles with allopurinol-induced SCARs in Koreans. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21:303–307. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834282b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lonjou C, Borot N, Sekula P, et al. A European study of HLA-B in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis related to five high-risk drugs. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:99–107. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f3ef9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goncalo M, Coutinho I, Teixeira V, et al. HLA-B*58:01 is a risk factor for allopurinol-induced DRESS and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in a Portuguese population. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:660–665. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung JW, Song WJ, Kim YS, et al. HLA-B58 can help the clinical decision on starting allopurinol in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:3567–3572. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jung JW, Kim DK, Park HW, et al. An effective strategy to prevent allopurinol-induced hypersensitivity by HLA typing. Genet Med. 2015;17:807–814. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ko TM, Tsai CY, Chen SY, et al. Use of HLA-B*58:01 genotyping to prevent allopurinol induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions in Taiwan: national prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4848. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirato S, Kagaya F, Suzuki Y, Joukou S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by methazolamide treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:550–553. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150552021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SH, Kim M, Lee KW, et al. HLA-B*5901 is strongly associated with methazolamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:879–884. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jee YK, Kim S, Lee JM, Park HS, Kim SH. CD8(+) T-cell activation by methazolamide causes methazolamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:972–974. doi: 10.1111/cea.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang F, Xuan J, Chen J, et al. HLA-B*59:01: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by methazolamide in Han Chinese. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;16:83–87. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang YY, Nguyen GH, Jin HZ, Zeng YP. Methazolamide-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in a man carrying HLA-B*59:01: successful treatment with infliximab and glucocorticoid. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:494–496. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shu C, Shu D, Tie D, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by methazolamide in a Chinese-Korean man carrying HLA-B*59:01. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1242–1245. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Her Y, Kil MS, Park JH, Kim CW, Kim SS. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by acetazolamide. J Dermatol. 2011;38:272–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lorenz M, Wozel G, Schmitt J. Hypersensitivity reactions to dapsone: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:194–199. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang FR, Liu H, Irwanto A, et al. HLA-B*13:01 and the dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1620–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caudle KE, Rettie AE, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C9 and HLA-B genotypes and phenytoin dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96:542–548. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ciccacci C, Di Fusco D, Marazzi MC, et al. Association between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and Nevirapine-induced SJS/TEN: a pharmacogenetics study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1909–1916. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]