Abstract

Background

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is prevalent in Sudan’s rural areas including Gezira state in central Sudan. We initiated a control program aiming at measurement of the echocardiographic (echo) prevalence of RHD, training of health workers and public awareness.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional and interventional study conducted in Gezira State, Al Managil Locality from Nov 2016 to February 2018. We used handheld echo (HHE) to detect the prevalence of RHD in school children and those tested positives were referred for standard echo. In addition, training on detection of RHD for health professionals was offered using training modules for physicians and nurses. Evaluation of health facilities was carried out using a questionaire. This was coupled with educational sessions to increase public awareness about RHD using posters and pamphlets.

Results

Two thousand and one hundred twenty-nine school children were screened, 36 cases were positive by HHE, out of these 31 underwent standard echo and 5 were confirmed to have RHD, giving an echo prevalence of 2.3/1,000. All cases had mild mitral regurgitation. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of 175 health workers were assessed then a tailored training program was implemented. Practices that are not compatible with Sudan’s RHD Guidelines were detected including performing skin testing prior to administration of benzathine penicillin and under-utilization of local anesthetic to decrease the pain when giving the injection. Benzathine penicillin was available in only 32% of health facilities and only 25% of their personnel received training in RHD management.

Conclusions

RHD echo prevalence in Gezira is relatively high and the health system needs to be strengthened. A double approach, screen-to-control program that utilizes HHE screening, health workers’ training, public awareness and providing medical supplies in primary health care centers is feasible.

Keywords: Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), children, heart failure, Sudan

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a devastating complication of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), a preventable sequelae of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection in young people living in underdeveloped countries. RHD is considered the most common cause of heart disease in people less than 25 years in Sudan and worldwide (1,2). In referral centers, it was noted that the majority of RHD patients come from certain states including Kordofan, Darfur, White Nile, Gezira and Sennar (3). A program for control of RHD was established in 2012 through collaboration between Sudan Heart Society and Federal Ministry of Health with the main objectives of surveillance, training and public awareness (3,4). An echocardiographic (echo) screening program was established in 2015, results from South Darfur and Khartoum showed a wide disparity in echo prevalence; 19/1,000 in Darfur and 0.3/1,000 in Khartoum (5). In Kordofan, west of Sudan a strikingly high echo prevalence of 61/1,000 was documented which correlated with the findings of the hospital registry where most patients came from Kordofan area (6). More echo screening programs are needed in order to map the prevalence of RHD in other states and consequently establish control programs in high burden areas. This study was carried in order to measure the echo prevalence and start a control program in Gezira state, central Sudan.

Methods

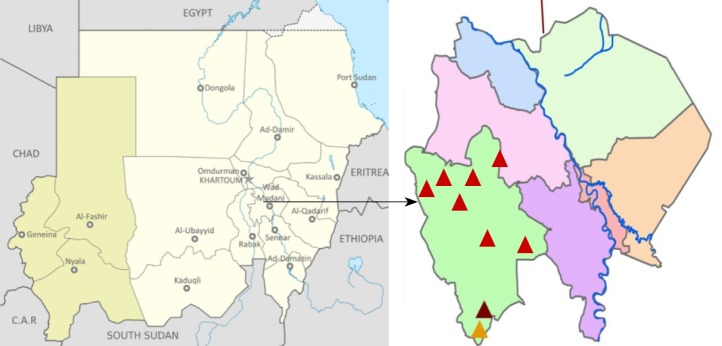

This project consists of 3 arms: a cross-sectional study to measure the echo prevalence of RHD and evaluate the health care centers’ readiness to manage the disease and a comparative interventional study to improve health workers knowledge and practices as well as the public awareness about RHD. It was conducted in Gezira State, Al Managil Locality in central Sudan from Nov 2016 to Feb 2018. Gezira has an area of 27,500 square kilometers and population of 2.8 million, mostly living in rural areas. There is a cardiac center in Wad Medani, the capital of Gezira State where pediatric and adult cardiology and cardiac surgery services are available. The poverty rate in Gezira is 37% (7) Al Managil locality, 46 kilometers from Wad Medani has a population of 99,500 (Figure 1). It was selected based on the finding of a relatively high rate of RHD patients coming to the heart center from this area.

Figure 1.

Sudan’s map (left), Al Managil area magnified with the 9 screening sites shown.

Echo screening

A sample size of 2,300 school children was calculated based on an estimated echo prevalence in Gazira of 10/1,000 derived from the average between Khartoum (0.3/1,000) and South Darfur (19/1,000) (5). All primary Schools in Al Managil were listed and a simple random sample was selected equally from both boys’ and girls’ schools. In each school, classes 5–8 were selected and all the pupils were invited to participate.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University of Khartoum, Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee. Administrative approval was obtained from Gezira State Ministry of Health and Al Managil Locality Health and School Authorities. Consent forms were distributed to the pupils through their school administrators and the pupils were instructed to show to their parents. Only those who agreed to participate were included in echo screening. Children with abnormal results and their families were counseled and advised to receive the appropriate treatment and follow up.

Echo protocol

Three handheld Echo (HHE) machines (V Scan—General Electric) were used. This machine has a single probe with a frequency 1.7–3.4 megahertz. It has storage capacity and a battery that lasts about 2.5 hours. A team of pediatric cardiology fellows and residents was trained on the use of HHE. A simplified “one view” protocol utilizing the parasternal long axis was adopted (8). Four images were recorded, two images using 2-dimensional echo and 2 with color Doppler. All the studies were recorded and stored to be reviewed offline by 2 pediatric cardiologists. Abnormal result was defined as definite or borderline by the modified WHF criteria (9).

Confirmation of abnormal HHE results

School children with abnormal results were called through their school administrators and the families were informed. Transportation was arranged to Wad Medani Heart Center where a standard echo (SE) study was performed for each child by a pediatric cardiologist using General Electric (Vivid 7) Echo machine. The standard echo protocol involves all the standard echo views and color as well as spectral Doppler, the later is not available in HHE machine.

Health workers’ training

A database of all health workers in Al Managil Locality was obtained from the health authorities. This includes physicians, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists and pharmacist assistants, health promoters and community health workers. Questionnaires were designed for physicians and for other health workers that included the following domains:

Diagnosis and management of streptococcal pharyngitis;

Diagnosis and management of ARF;

Administration of benzathine penicillin (BPG).

Visits to health facilities were conducted and the health workers were invited to attend training workshops that were arranged in Al Managil City. Three workshops were conducted and the questionnaires were filled before and after the workshop. The workshop material addresses the 3 above domains based on the Sudan’s Guidelines on Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease Management and Prevention (10). Practical sessions on administration of BPG were conducted with emphasis on certain practices, namely the workers were shown that there is no need to do skin testing using dilute BPG prior to the injection. They were trained on the use of lidocaine (local anesthetic) as a diluent for the BPG powder in order to reduce the pain.

Health facility evaluation

The health facilities in the locality were visited by the research team. A standardized questionnaire was used to collect information about staff numbers and training, medications, equipment and records.

Health education

School visits that were made to arrange for the Echo screening were used to introduce health education about ARF/RHF to school children and teachers using posters, pamphlets and video clips.

Statistical methods

For assessing prevalence of RHD: the ratio descriptive analysis was used in term of prevalence. For assessing readiness of health facilities simple absolute numbers and percentages was used. We assessed outcome variables pre and post intervention (training of healthcare providers). Chi square with point estimate P value was used an inferential statistic to test for significance. To evaluate interobserver agreement for the 2 cardiologists who interpreted the HHE studies, we randomly selected a sample of 30 echo studies and did a kappa test. Bias-adjusted kappa (equal to 2 × agreement-1) was used to determine the inter-observer agreement.

Results

Echo prevalence

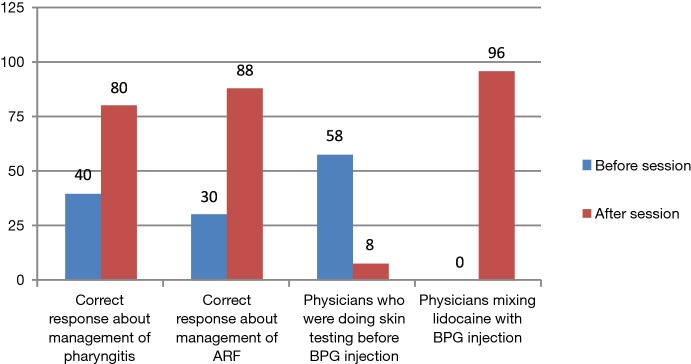

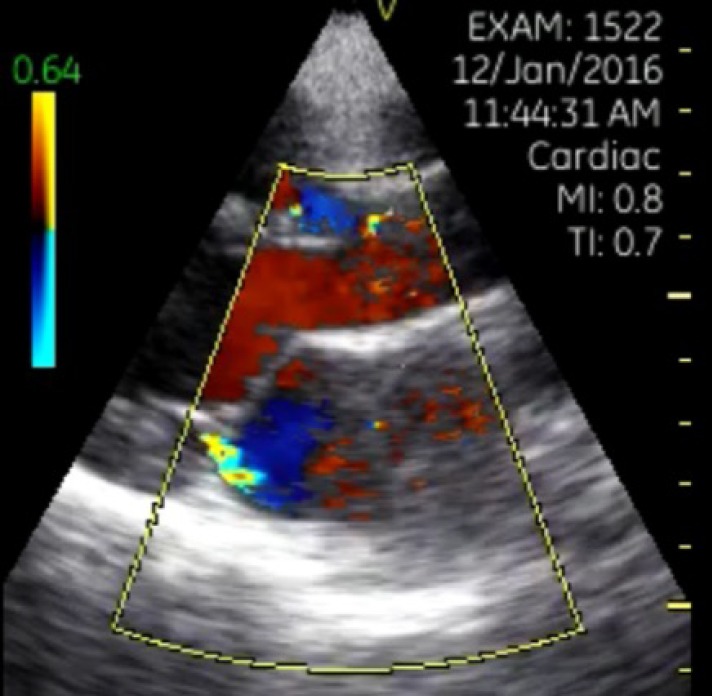

Ninety percent of children who were invited participated in the study. There were no differences in the response rate between the different sites. A total of 2,302 school children, age 11–15 years from 9 sites were screened (Figures 1,2). On reviewing the echo studies, 173 (8%) were found to be technically inadequate and were excluded. The remaining 2,129 were analyzed by 2 cardiologists. RHD was found in 36 cases (2%) using HHE, 20 had definite and 16 borderline RHD. Thirty-one children attended for SE at Wad Medani Heart Center and out of these, 4 cases were confirmed to have RHD, 20 had physiologic MR and 12 had a normal echo. Five children were not able to attend for SE for social reasons. The HHE studies of the five patients who did not attend for SE were reviewed for the third time and it was found that1had definite RHD (Figure 3), the remaining 4 had physiologic MR. Considering this case, the total number of cases of RHD is 5 (4 definite and 1 borderline) indicating a prevalence of 2.3/1,000 (Figure 2). All the positive cases have mild MR, in addition, the definite cases have thickened anterior mitral valve leaflet and chordate tendineae. None had AR or mitral stenosis. All patients with definite RHD were started on 3 weekly BPG injections. The child with borderline disease was asked to come for a follow-up echo in a 6 months’ time. Bias-adjusted kappa showed fair agreement between cardiologists (50%) with the diagnosis of definite versus borderline RHD.

Figure 2.

Schematic figure showing the outcomes of the echo study.

Figure 3.

Handheld echo image showing mild MR.

Other heart disease detected by HHE

The most common abnormality apart from RHD was mitral valve prolapse which was identified in 10 patients (prevalence of 4.6/1,000), one case of cardiomyopathy and one of aortic root dilatation were detected. All these cases were advised to attend for follow up.

Health workers’ training

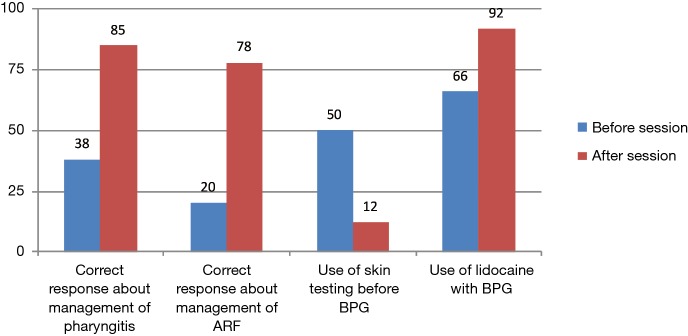

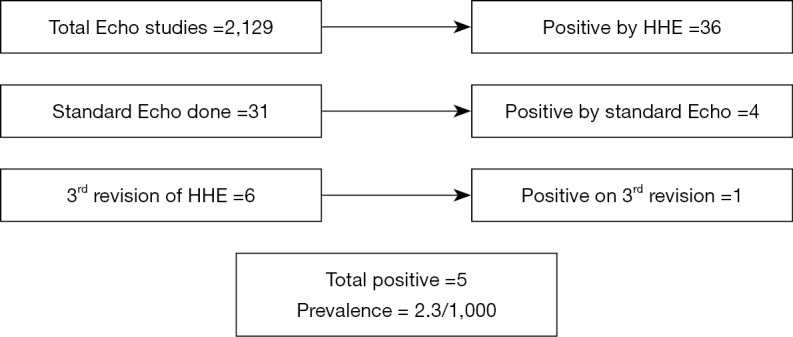

A total of 175 health workers were enrolled, 150 medical assistants/nurses and 25 physicians. The pre and post workshop knowledge of, attitudes and practice towards ARF and RHD were tested. The performance of physicians in answering the questions in regards to diagnosis and management of streptococcal pharyngitis, improved from 40 (before the session) to 80% (after the session) (P=0.032). Regarding knowledge about diagnosis and management of ARF, their performance improved from 30% to 88% (P=0.041). Before the session, 52% physicians were practicing skin testing using dilute BPG before giving the intramuscular injection, after the session, only 8% mentioned that a skin test is needed (P=0.011). None of the health workers was using lidocaine to decrease pain and, 96% of them changed their response after the session (P=0.001) (Figure 4). For medical assistants and nurses, the response to questions about management of bacterial pharyngitis improved from 38% to 85% (P=0.021). Response to questions regarding management of ARF improved from 20% to 78% (P=0.031) 50% of them were practicing skin test using dilute BPG and this decreased to 12% after the session (P=0.012). Only 66% were using of lidocaine as a diluent to decrease the pain of injection and this increased to 92% after the session (P=0.012) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Physicians’ response (%) to questionnaire before and after the training session.

Figure 5.

Health workers’ (%) response to questionnaire before and after the training session.

Health facilities

Forty health facilities were included, 32 (80%) were primary health centers and 8 (20%) were secondary centers. Availability of medications needed for management of RHD is shown in Table 1. Records for ARF and RHD were found in 9 (22.5%) and 7 (17.5%) of the centers respectively. Only 2 (5%) of the staffs in the studied centers received training on RHD management, the need for more training in management of ARF/RHD was reported by 24 (60%) of the staff.

Table 1. Percentage availability of items needed for RHD management in health facilities.

| Item | Availability (% of health facilities where it is available) |

|---|---|

| Benzathine penicillin | 32 |

| Adrenaline | 50 |

| Antihistamine | 95 |

| Lidocaine 2% | 95 |

| Syringe | 90 |

Health awareness sessions

Awareness sessions about prevention of ARF/RHD were delivered to school children and teachers in 12 primary schools (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

School children, teachers and research team member (HAH) during an awareness session.

Discussion

Sudan is the third largest country in Africa with a population of 34 million, poverty rate of 46.4%, per capita income of US$1,270, Its human development index is 0.490 with a ranking of 165. Poverty rates vary widely between 59% in Darfur, 37% in Gezira and 26% in Khartoum (7). The echo prevalence of RHD found in Al Managil of 2.3/1,000 is low relative to other areas in Sudan and to RHD-endemic countries, however, it is much higher than that in the capital Khartoum (0.3/1,000) (5) which correlated with the higher poverty rate of Gezira compared with Khartoum.

The prevalence in Al Managil is clearly lower than areas in Sudan such as South Darfur where an echo prevalence of 19/1,000 was documented (5), The latter is comparable to Mozambique (30.4/1,000) and Cambodia (21/1,000) (11) and other African countries such as Ethiopia (31/1,000) and in South Africa (20/1,000) (12).

On the other hand, the prevalence of 61/1,000 by HHE detected in North Kordofan (6) is extremely high and may reflect additional factors such as genetic susceptibility. While all the cases of RHD in Al Managil showed mild disease, 10% of cases from Kordofan manifested a severe form of RHD. Moreover, the number of valve lesions seen in Al Managil was less than Kordofan and Darfur where many cases of aortic regurgitation and mitral stenosis were detected (5,6). The relatively low prevalence in Al Managil could be explained by the semi-urban nature of the area, the better socioeconomic status and the proximity to large cities where there is a relatively better health care system compared to Kordofan and Darfur. Similar to the marked discrepancy that we found between Khartoum, Al Managil and Darfur, variations between urban and rural prevalence in the same country has been documented in other countries such as in South Africa (12). Ethnic and socioeconomic factors are recognized to affect the distribution of RHD within the same country. In New Zealand, the Maori/Pacific population and in Australian indigenous population RHD prevalence was disproportionately high compared to other ethnic groups (13,14). Beside the socio-economic and health system factors, genetic factors may be contributing to this discrepancy as there was lower rates of RHD in Sudan’s eastern and northern regions as recorded in the hospital register. It was shown that screening in primary health care centers yields more positive results than school screening and this may be contributing to the observed relatively low prevalence in Al Managil (15).

There was a high rate of positive cases by HHE studies compared with SE. This was due to the lower threshold to diagnose borderline RHD in patients with physiologic MR and mitral valve prolapse, both are relatively common and can lead to over diagnosis of RHD. As the overall rate of RHD was low, echo reviewers opted to include all cases of suspected RHD. A high rate of false positive had been reported by Beaton et al. and had been related to erroneous color Doppler jets and inappropriate measurement of the MR jet (16).

In addition to RHD, echo screening revealed a prevalence of mitral valve prolapse of 0.46% which is comparable to that reported in the literature of 0.5–1% (17).

Health workers knowledge of, attitudes and practice towards ARF/RHD were found to be poor and this is apparently due to the lack of training as has been documented in the health facility evaluation. Although the RHD control program was introduced in 2012, it is only recently that the Ministry of Health started implementing it in the rural states. Many of the health workers were using dilute BPG to perform a prick skin test for penicillin allergy prior to BPG injections, a widely prevalent practice which is not evidence-based. The use of lidocaine as a diluent for BPG in order to reduce pain, has been recommended by the Sudan’s guidelines, however, is not practiced by the health workers (10). The workshops helped to correct these practices that are crucial for BPG administration. Health worker training has a central role in RHD control programs that needs to be instituted to all levels of health care personnel including physicians and non-physicians (18). Successful programs such as in Cuba conducted training of health workers in primary care settings as part of other control measures such as registries and health awareness (19). Education of the public about RHD can effectively improve health seeking behavior and attitudes therefore, improves early diagnosis and treatment (20). This is particularly important as bacterial pharyngitis episodes can be mild and underreported to the health care providers. Similarly, ARF arthritis typically improves spontaneously and the patient will be missed during this critical window. Sudan adopted clear and consistent messages for public awareness (no sore throat, no sore joints) as shown in the photo. The situation of health facilities indicates a remarkable shortage in BPG, the cornerstone of RHD management. This drug is listed as an essential medicine; however, it was available in only 32% of health facilities. Only few staff received training about RHD management and most of them expressed their desire to have more training. These findings indicate the need for more training of health workers and provision of necessary medical supplies through a Ministry of Health sustainable program. This study, as well as the similar studies in Kordofan and Darfur utilized HHE screening as a tool to map the disease in order to identify the high burden areas and consequently established control measures: a double approach policy. Many studies were conducted in Africa and other RHD endemic countries aiming to measure the echo prevalence of RHD, however, few combined echo screening with establishing control measures. We adopted this double approach model: “screen-to-control” which is feasible using local health system competencies. We recommend implementing this approach at primary health care level in RHD-endemic areas. HHE has proven efficacy, therefore, referring to SE may not be needed if the health personnel are well trained.

Conclusions

RHD echo prevalence in Al Managil-Gezira is higher than Khartoum but it is significantly lower than that of Kordofan and Darfur. A double approach control program that utilizes HHE screening together with establishing control measures has been implemented. The study identified important gaps in the health system of the area.

Limitations

The children who did not attend for standard echo may have an important effect on the final echo prevalence. Screening was done in schools rather than the community and this may underestimate the prevalence.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the Sudanese American Medical Association for donating handheld echo machines and for co-funding of this project. We would like to acknowledge the following people who participated in or facilitated echo screening: Dr. Mohamed Elfatih Al Badri, Mr. Sami Ahmed, Dr. Hasan Awadallah, Dr. Nusaiba Al Khidir, Dr. Mohamed Hassan, Dr. Malak Ibrahim, Dr. Mugahid Ahmdia and Dr. Mahir Mohamed.

Funding: This project was co-funded by MIRAGLO Organization-USA and Sudanese American Medical Association.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the University of Khartoum, Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee. Administrative approval was obtained from Gezira State Ministry of Health and Al Managil Locality Health and School Authorities. Consent forms were distributed to the pupils through their school administrators and the pupils were instructed to show to their parents.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Suliman A. The state of heart disease in Sudan. Cardiovasc J Afr 2011;22:191-6. 10.5830/CVJA-2010-054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global Health Statistics. Harvard University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali S, Elseed A, Subahi S, et al. Sudan Rheumatic Heart Disease Control Initiative: achievements and challenges: 2012-2017. Sudan RHD Control Committee. Sudan Heart J 2017;4:50-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali SK. Rebuilding the rheumatic heart disease program in Sudan. Glob Heart 2013;8:285-6. 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali S, Domi S, Abbo B, et al. Echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease in 4515 Sudanese school children: marked disparity between 2 communities. Cardiovasc J Afr 2018;29:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali S, Domi S, Elfaki A, et al. The echocardiographic prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in North Kordofan and initiation of a control program. Sudan Med J 2017;53:63-8. 10.12816/0039456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudan: intrem poverty reduction strategy paper, International Monetary Fund 2012. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2013/cr13318.pdf

- 8.Zühlke LJ, Engel ME, Nkepu S, et al. Evaluation of a focused protocol for hand-held echocardiography and computer-assisted auscultation in detecting latent rheumatic heart disease in scholars. Cardiol Young 2016;26:1097-106. 10.1017/S1047951115001857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297-309. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali S, Alkhalifa MS, Khair SM. Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease, Sudan’s Guidelines for diagnosis, management and control. Available online: http://sudankidsheart.org/images/rhd/ARF_RHD%20Book.pdf

- 11.Marijon E, Ou P, Celermajer DS,, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiographic screening. N Engl J Med 2007;357:470-6. 10.1056/NEJMoa065085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel ME, Haileamlak A, Zühlke L, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in 4720asymptomatic scholars from South Africa and Ethiopia. Heart 2015;101:1389-94. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milne RJ, Lennon DR, Stewart JM, et al. Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in New Zealand children and youth. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:685-91. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parnaby MG, Carapetis JR. Rheumatic fever in indigenous Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health 2010;46:527-33. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nascimento BR, Sable C, Nunes MC, et al. , the PROVAR (Rheumatic Valve Disease Screening Program) Investigators. Comparison Between Different Strategies of Rheumatic Heart Disease Echocardiographic Screening in Brazil: Data From the PROVAR (Rheumatic Valve Disease Screening Program) Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e008039. 10.1161/JAHA.117.008039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaton A, Nascimento BR, Diamantino AC, et al. Efficacy of a Standardized Computer-Based Training Curriculum to Teach Echocardiographic Identification of Rheumatic Heart Disease to Nonexpert Users. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1783-9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warth DC, King ME, Cohen JM, et al. Prevalence of Mitral Valve Prolapse in Normal Children. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5:1173-7. 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80021-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyber R, Grainger Gasser A, Thompson D, et al. Tools for Implementing RHD Control Programmes, Quick TIPS Summary. World Heart Federation and RhEACH. Perth, Australia 2014. Available online: https://rhdaction.org/sites/default/files/QUICK-TIPS_World-Heart-Federation_RhEACH.pdf

- 19.Nordet P, Lopez R, Duenas A, et al. Prevention and contol of rheumatic heart disease: the Cuban experience (1986-2002). Cardiovasc J Afr 2008;19:135-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsey LS, Mary, Watkins L, Engel ME. Health education interventions to raise awareness of rheumatic fever: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2013;2:58. 10.1186/2046-4053-2-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]