Abstract

Objective

HIV cognitive impairment (HACI) continues to persist for HIV-seropositive individuals who are on antiretroviral therapy (ART). HACI develops in part when HIV-infected monocytes (MO) transmigrate through the blood brain barrier (BBB) and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines which leads to neuronal damage. In-vitro BBB models are important tools that can elucidate mechanisms of MO transmigration. Previously described in-vitro BBB models relied on pathology specimens resulting in potentially variable and inconsistent results. This project reports a reliable and consistent alternative in-vitro BBB model that has the potential to be used in clinical research intervention studies analyzing the effects of ART on the BBB and MO transmigration.

Methods

A bilayer BBB was established with commercially available astrocytes and endothelial cells on a 3μm PET membrane insert to allow contact of astrocytic feet processes with endothelial cells. Inserts were cultured in growth medium for seven days before exposure to HIV− or HIV+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). PBMC were allowed to transmigrate across the BBB for 24 hours.

Results

Confluency and integrity measurements by trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) (136.7 ± 18.3Ω/cm2) and permeability (5.64 ± 2.20%) verified the integrity of the in-vitro BBB model. Transmigrated MO and non-MO were collected and counted (6.0×104 MO; 1.1×105 non-MO). Markers indicative of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and p-glycoprotein (Pgp) were revealed in immunofluorescence staining (IF), indicating BBB phenotype and functionality.

Conclusion

Potential applications for this model include assessing HIV DNA copy numbers of transmigrated cells pre- and post-targeted ART and understanding the role of oxidative stress related to HIV DNA and HACI.

Keywords: HIV, cognition, blood brain barrier, neurocognition, brain

1. Introduction

Persistence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV)-associated cognitive impairment (HACI) remains a major morbidity concern for patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) (1). Previous data suggested that residual chronic central nervous system (CNS) inflammation was a factor in HACI pathogenesis however some patients experience cognitive improvement while on ART, implying CNS impairment might be reversible (2).

High HIV DNA copy numbers in monocytes (MO) were found in patients with HACI compared to patients with normal cognition (3, 4). Increased HIV DNA levels in CD14+ cells from cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) correlated with worse HACI (5). To identify strategies to study MO as targets for novel treatment paradigms, in-vitro BBB models have been described using both mono- and bi-layer BBB models (6, 7). As a monolayer, brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) are crucial to BBB models because they provide vascular tight junctions (8). However, endothelial-only BBB models are limited since the BBB is multi-layered (9). Addition of astrocytes regulates tight junctions and helps facilitate cellular trafficking (10). Evidence of increased integrity and function of BMVEC through interaction with astrocytes would contribute to the benefits of a bi-layer BBB model.

BBB models typically utilize fresh fetal brain tissues to isolate astrocytes (11, 12). Challenges in isolating astrocytes is maintaining quality control of the cells as well as tissue viability and availability. (13). Thus, an in-vitro BBB model using astrocytes from more reliable resources would be valuable. While previous studies used a time-intensive procedure for isolating primary astrocyte/pericyte cells (14), commercially available astrocytes could reduce the necessary time to culture cells and provide a dependable source.

An in-vitro bi-layer BBB model was adapted for use in a clinical research study to assess changes in MO transmigration which was adapted for clinical research. The integrity of the model was assessed by trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) to test tight junctions and Evan’s blue dye-conjugated to bovine serum albumin (EBA) to test BBB permeability which was further validated by immunofluorescence. The data demonstrated reproducible in-vitro BBB characteristics over time which could be a useful tool in future clinical translational research studies.

2. Materials and Methods

A previously described in-vitro BBB model utilized primary fetal human astrocytes (AC) and primary human endothelial cells (EC) (11). To improve consistency and reproducibility, this report describes an adaptation of the model to improve consistency and reproducibility using commercially-available cells.

2.1 Astrocytes and Endothelial Cells

Primary adult human AC and EC cells (Angio-Proteomie, Boston, MA) were established on plates that were initially coated with 0.2% porcine skin gelatin at room temperature. Cells were seeded in astrocyte (AGM) or endothelial (EGM) growth medium (Angio-Proteomie). Media was changed every 2-3 days until confluency was reached. Cells were used between 5 to 10 passages.

2.2 Blood Brain Barrier Model

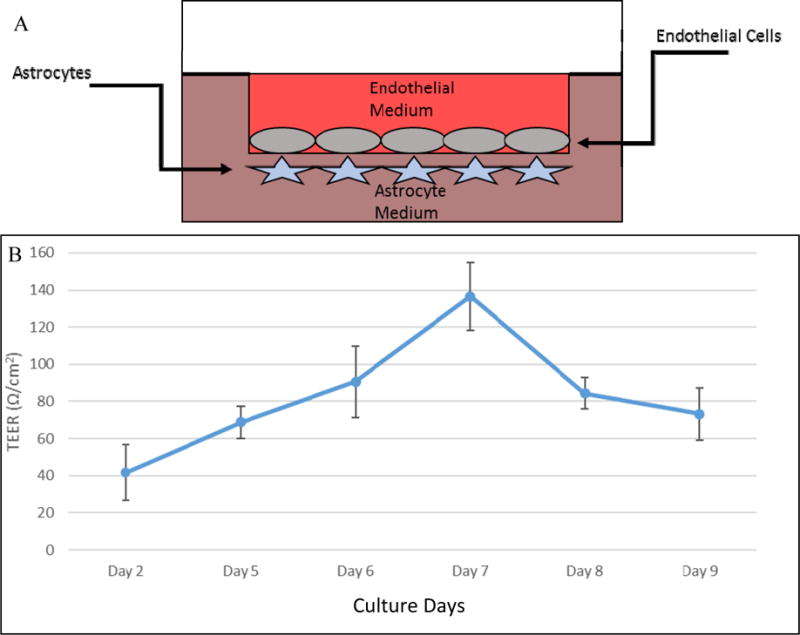

Cell culture inserts (Falcon, BD Biosciences, Billerica, MA) with 3μm pores and surface area of 0.3cm2 were first coated with 0.2% gelatin on both sides. AC (1.2×105 cells) were placed on the underside of the trans-well insert and incubated at 37°C. The inserts were flipped and placed into a 24-well trans-well plate with AGM. EC (1.2×105 cells) were then seeded to the inside of the insert. Media was changed every 2-3 days until confluency was reached at 7 days as assessed by TEER and EBA permeability (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the blood brain barrier model. Astrocytes are cultured on the underside of the trans-well insert and flipped into a well with AGM. Endothelial cells are then cultured on the inside of the barrier and fed with EGM. PBMC are introduced from the endothelial side and allowed to transmigrate to the astrocyte layer after 24 hours (A). Trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) over time. TEER values (Ω/cm2) of the bilayer BBB model over the course of 9 days (n=6). Data showed peak point at day 7 where inserts reached maximum confluency when media were changed to BGM for transmigration experiments (B).

2.3 Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC)

Whole blood was obtained from volunteers (HIV-seronegative and -seropositive) as per guidelines established by the University of Hawaii Institutional Review Board. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) gradient.

2.4 In-Vitro Transmigration

Media was removed from inserts and inserts were transferred to a new 24-well plate containing FBS/BGM with SDF1-α (R&D Systems). The inserts were layered with 1×106 PBMC per insert for 24 hours.

2.5 Blood Brain Barrier Integrity Assessment

At day 7, inserts were selected at random to assess permeability of the BBB by EBA and BBB integrity by TEER (11, 15). Media was aspirated from the upper chamber and transferred to a new well and washed with phenol-red free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM).

The insert was transferred to a new well containing FBS/DMEM. To test permeability, EBA was added to the upper chamber and incubated at 37°C. Flow-through was analyzed at 620nm using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). EBA permeability was evaluated before and 24 hours after PBMC introduction. TEER was analyzed using an epithelial voltmeter (EVOM) (World Precision Instruments).

2.6 Immunofluorescence

On day 7, inserts were selected at random and moved to a new plate with paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS added to astrocyte and endothelial sides of the insert and fixed. After fixation, the membrane of the inserts was cut out of the barrier and placed in OCT in a mounting block and cross-sectioned and mounted on slides (Leica Biosystems; Nussloch, Germany). The cross-sections were permeabilized using Triton-X100 and blocked (EDTA, fish gelatin, BSA, horse serum). Primary antibodies for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), von Willebrand factor (vWF) and p-glycoprotein (pGP) were added, followed by secondary antibodies, and visualized using the Zeiss Axioskop 2 Plus fluorescent microscope.

3. Results

3.1 TEER and EBA Permeability

TEER resistance increased steadily on consecutive days with maximum resistance measured on Day 7. Resistance steadily decreased after Day 7 with no BGM media change (Figure 1B).

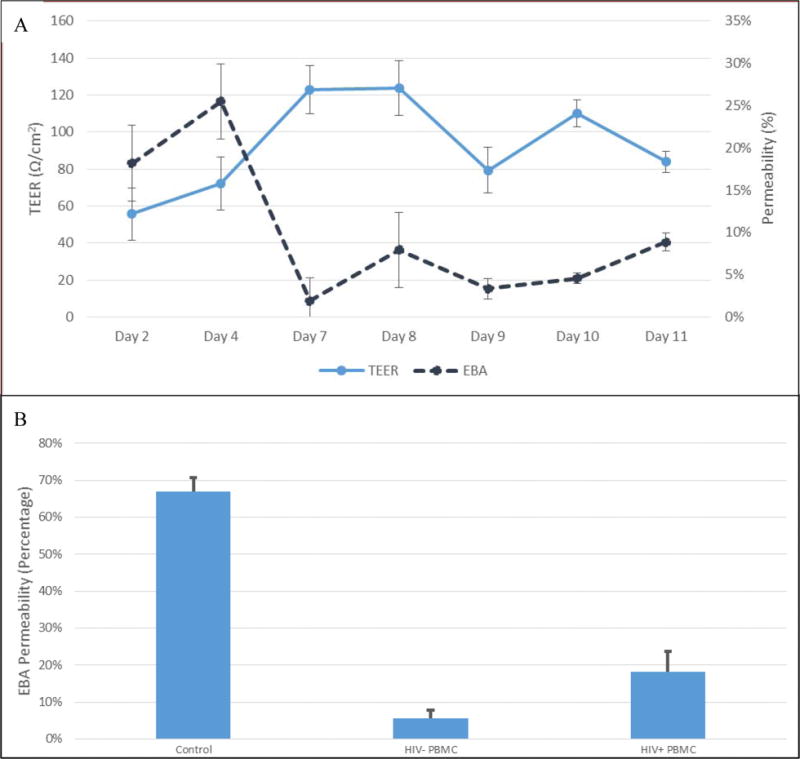

After switching to BGM for the barriers, the resistance and permeability values were stable over time. Both the values of TEER and EBA permeability were measured after introduction of BGM (Figure 2A). Statistical analysis by ANOVA showed no significant differences in TEER and EBA and maintained values of ~100 Ω/cm2 (p=0.065) and <15% (p=0.075) respectively over 5 days.

Figure 2.

Trans-endothelial electronic resistance (TEER) pre- and post-media switch. All measurements are made after media has been changed for that time point. TEER values (n=24) before and after basal growth media (BGM) switch (media change at Day 7). TEER remains elevated and is validated with low EBA permeability. Permeability of these barriers (n=24) initially are high (>15%); the permeability of the barriers decreases and maintains at optimal values after BGM switch (<15%). Analysis by ANOVA showed that there are no significant differences between TEER and EBA values between days 7-11 (p=0.065 and =0.075 respectively) (A). Evan’s blue albumin (EBA) permeability. EBA permeability values (n=3) of a control insert (no cells) and the-bilayer model after transmigration of HIV-negative and HIV-positive PBMC. The bi-layer model demonstrated high level of membrane integrity and low EBA permeability after HIV− transmigration and showed significant integrity loss after HIV+ PBMC transmigrated (p = 0.00405) (B).

Initial tests of the BBB model showed stabilization of permeability after the addition of basal growth medium (BGM) and maintained a value of 7.73 ± 0.87%. Control wells showed permeability values of ~65%. HIV-negative PBMC transmigration resulted in no BBB integrity compromise. Transmigration of HIV+ PBMC displayed a significant increase in EBA permeability as assessed by an independent two-sample t-test (p=0.004) (Figure 2B).

3.2 Immunofluorescence

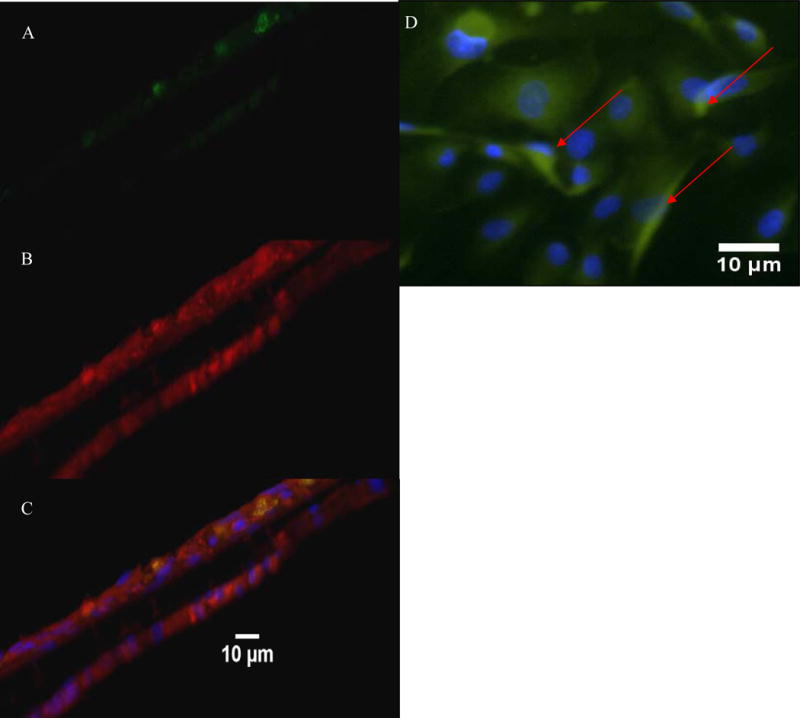

Our model exhibited phenotypes presence of functional proteins; vWF and GFAP are both shown on a cross section of our barrier. GFAP was imaged on both sides of the barrier. Staining for pGP shows presence of an efflux transporter on our endothelial cell cultures (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cross sectional and top view staining of the BBB model for quality assessment of the presence of functional proteins. vWF staining shown in green (A) and GFAP staining shown in red (B). The merged view of the image showing the co localization of the astrocytes and endothelial cells with nuclei of cells in blue (C). Top view endothelial cells show the nucleus in blue and the Pgp transporters in green. Arrows point to the transporters (D).

3.3 Transmigration

Cell count data showed transmigration of 10% of initial cell population (1×106 cells) per insert. PBMC were collected after transmigration and pooled from 20 wells and retrieved. Cells were collected and re-suspended in PBS and filtered (Celltrics 30μm). Cells were separated by CD14− Negative Selection MO Enrichment (STEMCELL Technologies) on the Robosep and counted. After cell separation, 6.0×104 MO were found to transmigrate per insert for the BBB model.

4. Discussion

The BBB model that was adapted was reproducible and demonstrated integrity and reliability. Using TEER to measure functionality of tight junctions, the model was consistent with other studies (16). TEER values decreased after reaching maximum confluence possibly due to cell overgrowth as previously reported (17). EBA permeability was also consistent with other studies which is typically impermeable to an intact BBB (11, 18). The combination of low EBA permeability and high TEER values indicated a barrier with integrity and junctions.

The model also showed human BBB characteristics. vWF and GFAP are markers of endothelial cells and astrocytes, respectively. GFAP presence on both sides of the barrier was consistent with pores that stretched from one side of the membrane to the other suggesting that astrocytes can physically contact the endothelial cells which is desirable as astrocytic feet processes are regulators of endothelial cells. pGP is a “gatekeeper” in the BBB and is a major influence on drug trafficking as it is broadly complementary to many substrates and acts as an efflux transporter to move these substances out of the brain and into the blood stream.

Transmigration of MO through the BBB was also of interest to adapt the model for clinical research studies. CD14+ cells isolated from the transmigration of PBMC could be further analyzed for HIV DNA content. Previously, CD14+ cells were shown to directly correlate with increased brain injury and CSF immune activation (19). Circulating HIV-infected MO were hypothesized to contribute to HACI by heightened pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress (14). A review on HACI and oxidative stress by Valcour & Shiramizu proposed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as an additional factor leading to impaired cognitive performance (20). An exploration of mtDNA in CD14+ cells after transmigration and their role in oxidative stress could provide avenues for more therapeutic options for HACI.

This adapted in-vitro BBB model was reliable and consistent in PBMC transmigration which can be applicable for future clinical research intervention trials. The stability of the BBB could provide a window of opportunity in a clinical trial setting for research visits relying on clinical specimens in clinical translational studies. To further understand the pathogenesis of HACI, the BBB could be a tool to study oxidative stress mechanisms and the impact of HIV-infected transmigrated cells in the setting of intervention clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Hawaii Center for AIDS research lab, clinical personnel and clinical lab for support; funding sources R01MH102196, U54MD007584, U54MD008149 (RCMI Translational Research Network) and G12MD007601. Appreciation to Dr. Joan Berman, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY for providing the foundation to establish the BBB model.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Influence of HAART on HIV-related CNS disease and neuroinflammation. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2005;64:529–536. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiramizu B, Ananworanich J, Chalermchai T, et al. Failure to clear intra-monocyte HIV infection linked to persistent neuropsychological testing impairment after first-line combined antiretroviral therapy. Journal of neurovirology. 2012;18:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valcour VG, Shiramizu BT, Sithinamsuwan P, et al. HIV DNA and cognition in a Thai longitudinal HAART initiation cohort: the SEARCH 001 Cohort Study. Neurology. 2009;72:992–998. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344404.12759.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agsalda-Garcia M, Shiramizu B, Melendez L, et al. Different levels of HIV DNA copy numbers in cerebrospinal fluid cellular subsets. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2013;24:8–16. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McFarren A, Lopez L, Williams DW, et al. A fully human antibody to gp41 selectively eliminates HIV-infected cells that transmigrated across a model human blood brain barrier. AIDS. 2016;30:563–572. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DW, Anastos K, Morgello S, Berman JW. JAM-A and ALCAM are therapeutic targets to inhibit diapedesis across the BBB of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in HIV-infected individuals. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2015;97:401–412. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5A0714-347R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luissint AC, Artus C, Glacial F, Ganeshamoorthy K, Couraud PO. Tight junctions at the blood brain barrier: physiological architecture and disease-associated dysregulation. Fluids and barriers of the CNS. 2012;9:23. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradbury MW. The blood-brain barrier. Experimental physiology. 1993;78:453–472. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1993.sp003698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature09513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Chemokine-dependent mechanisms of leukocyte trafficking across a model of the blood-brain barrier. Methods. 2003;29:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agsalda-Garcia M, Williams DW, Berman JW, et al., editors. Journal of neurovirology. SPRINGER; 233 SPRING ST, NEW YORK, NY 10013 USA: 2013. Characterizing HIV-Infected Monocytes that Transmigrate Across an In-Vitro Blood-Brain-Barrier as a Tool to Study HAND Pathogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du F, Qian ZM, Zhu L, et al. Purity, cell viability, expression of GFAP and bystin in astrocytes cultured by different procedures. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2010;109:30–37. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valcour VG, Shiramizu BT, Shikuma CM. HIV DNA in circulating monocytes as a mechanism to dementia and other HIV complications. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2010;87:621–626. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma S, Kumar M, Gurjav U, Lum S, Nerurkar VR. Reversal of West Nile virus-induced blood-brain barrier disruption and tight junction proteins degradation by matrix metalloproteinases inhibitor. Virology. 2010;397:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan B, Kolli AR, Esch MB, et al. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. Journal of laboratory automation. 2015;20:107–126. doi: 10.1177/2211068214561025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li G, Simon MJ, Cancel LM, et al. Permeability of endothelial and astrocyte cocultures: in vitro blood-brain barrier models for drug delivery studies. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2010;38:2499–2511. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0023-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE. Development of laboratory and animal model systems for HIV-1 encephalitis and its associated dementia. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1997;62:100–106. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valcour VG, Ananworanich J, Agsalda M, et al. HIV DNA reservoir increases risk for cognitive disorders in cART-naive patients. PloS one. 2013;8:e70164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valcour V, Shiramizu B. HIV-associated dementia, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]